After white supremacist Dylann Roof gunned down nine people in Charleston’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in 2015, Johnathon Kelso began traveling the South, intent on unearthing and photographing “the darkest part of our history.” Many of these images are difficult to look at. But if we want to move into a better South, we must rise above the twisted mythologies of the “Old South.” These photos show how deeply those myths have tangled themselves into certain pockets of Southern society. If anything, Kelso’s photographs prove how much untangling remains to be done.

Photos and Words By Johnathon Kelso

One month after my first son was born, I attended a Southern photography getaway in the Black Belt of Alabama. The question was asked, "What is a Southern image?" I chewed on it some, not knowing the exact answer, and decided I'd better find out for myself. I began photographing lone country roads, genteel Southerners, and familiar scenes of Jesus lovers. Was this what it meant to be a Southerner?

I have always thought of myself as a Southerner. Born and raised in the Florida panhandle, I've lived in Arkansas, Tennessee and Georgia. I have a strong sense of belonging to the land and its culture. But as a photographer representing the South, I want to dig into my own Southern identity a bit more. I want to know exactly what I'm claiming when I call myself a “Southern artist.” Do I believe in the Southern trinity of Elvis, Jesus, and Robert E. Lee? Could I swear it, like Scarlett O'Hara did, with God as my witness?

Then, the unthinkable happened. Dylann Roof walked into a evening prayer service at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in downtown Charleston, South Carolina, and murdered nine church members before fleeing the scene. Almost instantly after his arrest, an image appeared online showing Roof posing with a handgun in front of a Confederate battle flag. I felt an immediate pull away from my Southerness and a sense of shame for our broken past.

To look intently on the South, I needed to look at the darkest part of our history to see if there was any truth or beauty I can abide with. So I sought out the Sons of Confederate Veterans and those who still wave the rebel flag. I spent time with people labeled as racists, rednecks, country folk, and in some cases, those labeled by the Southern Poverty Law Center as extremists. I spent time with and photographed people caught up, sometimes incidentally, in public reenactments or “tributes” to the Confederacy. I also spent time with authors, historians, and documentarians to level the playing field. Through some digging, I even discovered that my own third great-grandfather, William Kelso(e), fought for the Confederacy in the 19th Alabama Infantry, Company B.

As I photographed Confederate memorials and rallies across the Bible Belt, I realized I was witnessing a dying culture. “As God Is My Witness” is an attempt to document what remains of this version of the South today, not some glorified Old South of the past. Both as a Christian and as a photographer, my task is to listen and practice empathy, to peer beyond the veil of America's only “felt" history and accept it.

“We can’t rewrite history. But we can correct some of the evils of history.”

— John Cummings, founder of the Whitney Plantation Museum, Wallace, Louisiana

After finishing my project, I sat it aside and tried to put some space between myself and the distorted visions of Tara that I had photographed over the past year. During that down time, I came across two pieces in The New Yorker. One article described a black lawyer in Montgomery, Bryan Stevenson, who had plans to raise a monument to commemorate the victims of “racial terror lynching” in the South. The other — a 12-minute documentary film — told of a white lawyer, John Cummings, who had reopened the doors of the Whitney Plantation to tell its story of slavery in Louisiana. What struck me most about these two men was their ability to look at our past, warts and all, and enter into a grand conversation about it, so that healing can begin. Our history of slavery, of lynchings, of convoluted ideas about human rights … are we as Southerners supposed to turn a blind eye to all this and struggle through proudly? I think not.

In the film, Cummings says, “It may be that you’re not forgetting because you never knew … because of a conscious elimination from history.”

As heavy-laden Confederate sentiment dissipates and the landscape of the South begins to wear in a brand new groove of post-Civil War enlightenment, we can’t all go on thinking that the Confederates in the attic will disappear if only we shut our eyes just tight enough and stop up our ears so we do not hear the faintest of rebel yells. What would it look like to take on the task of looking our neighbors in the face today, no matter which side of history they are on, and with God as our witness, loving them well now, to show the world a less bitter South than history books have taught us?

Mother and Daughter

Atlanta, Georgia

This image of a mother and daughter at a local meat-and-three in Atlanta was taken about a month before the shootings at Mother Emanuel and was one of the first images made for this series. My intention at the time was only to understand my own Southern identity, so, I began photographing distinctly familiar scenes in the hope that some visual would help me answer the question, "What is a Southern image?" I was in search of images that captured the South. But after the massacre, I realized that to find real truth about our region, I would also have to look in darker places.

Wildman

Kennesaw, Georgia

Dent "Wildman" Myers, owner of Wildman's Civil War Surplus in Kennesaw, Georgia. Wildman's shop has been in business since 1971, selling Confederate memorabilia, antique weaponry, and racist literature. Wildman believes he is the reincarnation of Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson and was awarded Kennesaw's first Historic Preservation Award in 1993.

Gregory Newson

Decatur, Georgia

Gregory Newson is an example of the many unlikely people I met along this journey. Newsom says he had a daydream while listening to a 1963 speech by Malcolm X entitled, “Message to the Grass Roots.” Struggling with his own identity as a black man in America, Newson felt called to "produce art concerning the human condition and internal war we all battle." His children's book, “Uncle T and the Uppity Spy,” is a semi-fictional tale of the relationship between Gen. Stonewall Jackson and his slave, Jim Lewis. Newson hopes to gain recognition of the black Confederates’ cause during the Civil War.

Tanner’s Church

Ellenwood, Georgia

Established in 1834, Tanner's Baptist Church in Ellenwood, Georgia, is one of the oldest existing churches in Clayton County. Due to a mishandling of church records, however, there were no known records of Confederate dead buried in the old churchyard nearby. Then, Shannon Bradley Byers, who claims to be the South's only “paranormal genealogist,” discovered records pointing her in the direction of Tanner's Baptist Church as she searched for the remains of her Confederate ancestor, William Redding Byers. With the help of the local Sons of Confederate Veterans chapter and the church, Byers’ name was entered into the record at Tanner's, and a service was held in his honor on September 20, 2008.

Highway 41 near Morriston, Florida

Growing up in the South, I saw church signs like this everywhere. Their slogans of invitation and rebuke are hard to miss, and for better or worse have shaped how I view the God of all creation. As I struggled to find meaning in my own Southern identity, I looked to the Southern landscape for clues in who I was supposed to be, not only as man in the South, but also as a man in Christ.

Joe Jordan

Atlanta, Georgia

Joe Jordan, commander of the Sons of Confederate Veterans’ John B. Gordon Camp 46, stands outside Mary Mac's Tea Room in downtown Atlanta, Georgia, where the SCV’s monthly meeting is held. The evening this photo was taken, I witnessed the predominantly African-American staff at Mary Mac’s serve a round table of aging white men discussing the “War of Northern Aggression” and their fervent desire to maintain the values and principles upheld by their Confederate forefathers.

Reenactor

Lovejoy, Georgia

A Civil War reenactor takes part in the annual staging of the Battle of Lovejoy's Station, held at Nash Farm Battlefield in Hampton, Georgia. The battle took place in the

summer of 1864.

Nash Farm Battlefield

Lovejoy, Georgia

A local attends the annual Battle of Lovejoy's Station reenactment. This historic battlefield and what's left of its 100 acres is nestled between Henry and Clayton Counties. Threatened by development and urban sprawl, the local community stepped forward to buy back the land and establish it as a historic park commemorating the battle. The park stands today on the list of Most Endangered Civil War Battlefields, according to the Civil War Preservation Trust.

Union Soldiers

Lovejoy, Georgia

Young Southerners dress as Union soldiers for the annual reenactment at Nash Farm Battlefield.

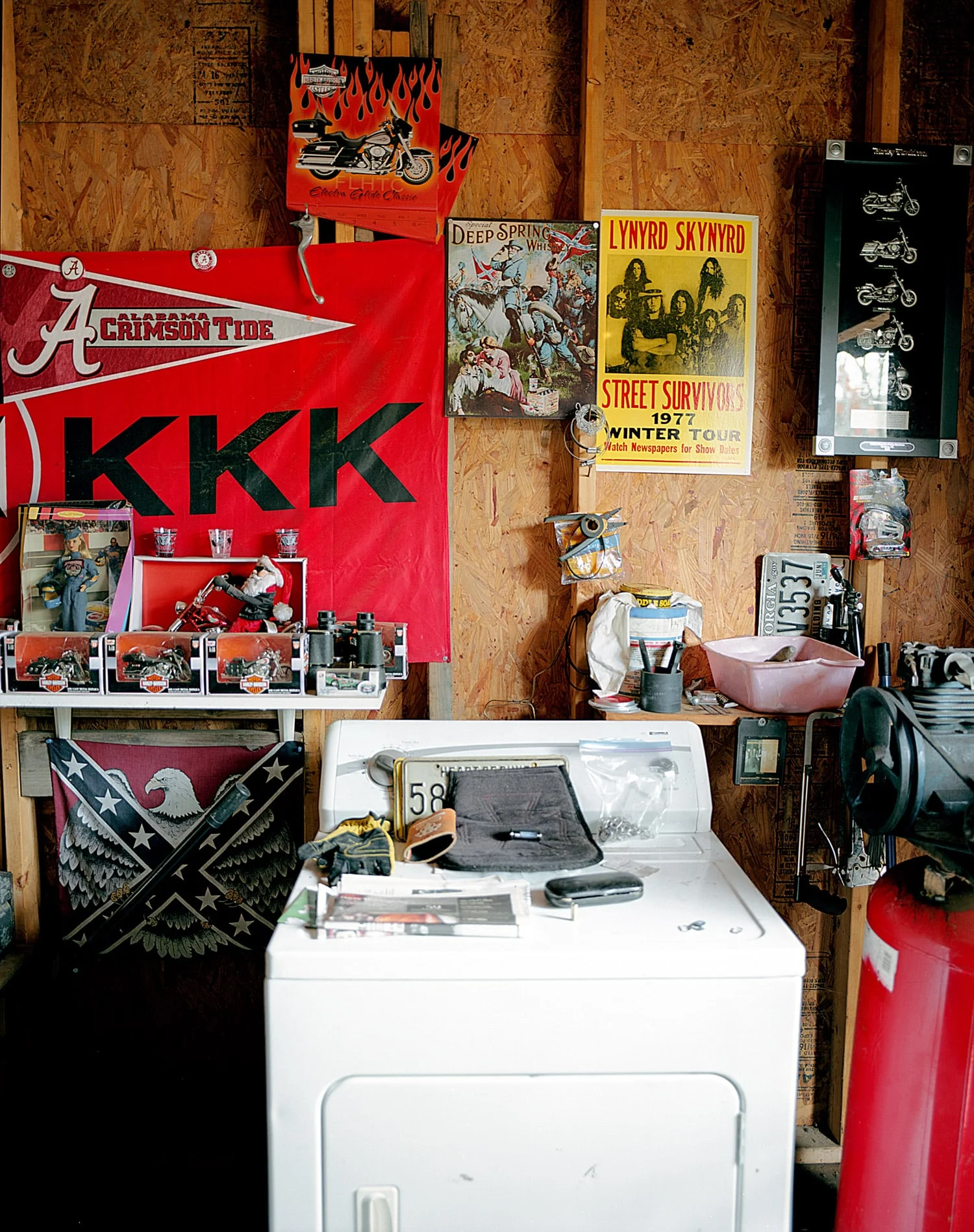

King's Shed

Draketown, Georgia

Neighbors in Villa Rica, Georgia, awoke to Ku Klux Klan flyers on their driveway one November morning. In my search to find who made them, I came up empty. Instead, I drove around aimlessly hoping to find a worthwhile lead. I stopped when I saw James King sitting outside his "man cave," which is outfitted in KKK and Confederate decor. King said he was an ex-Klan member who grew tired of the “inside politics.” King gave me a tour of his hangout and let me hold one of the rabbits he raises for meat.

Church Fan

Hardeman Primitive Baptist Church

I didn’t grow up in the church. In fact, most of my life, I held views of agnosticism and atheism. Growing up in the South, I felt a sense of what God’s people were like, and sure enough, I wanted nothing to do with them. I remember on one occasion two boys came to me and asked, "If you died today, would you go to heaven or hell?" Before I could answer, one of the boys said, "Hell." Despite this encounter and many others like it, in 2009 I was seized by the power of a great affection, namely, Jesus Christ. He spoke to me, and I became his disciple. After being baptized, I began trying to model my life after God, with his help. Throughout this series, “As God Is My Witness,” I turn back to the Southern landscape to help gain understanding of my newfound identity in Christ and leave behind the old views I once held, in light of the new.

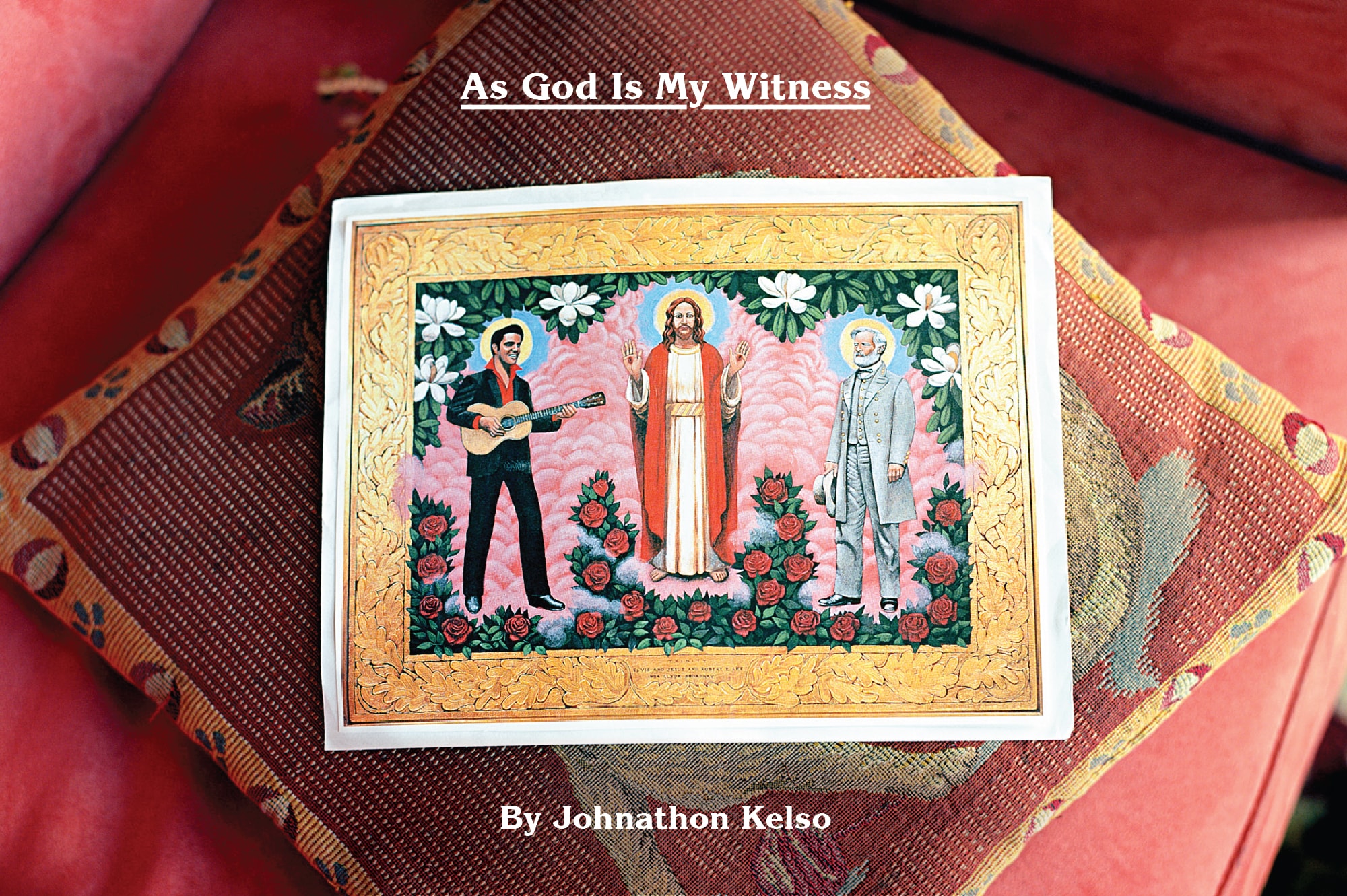

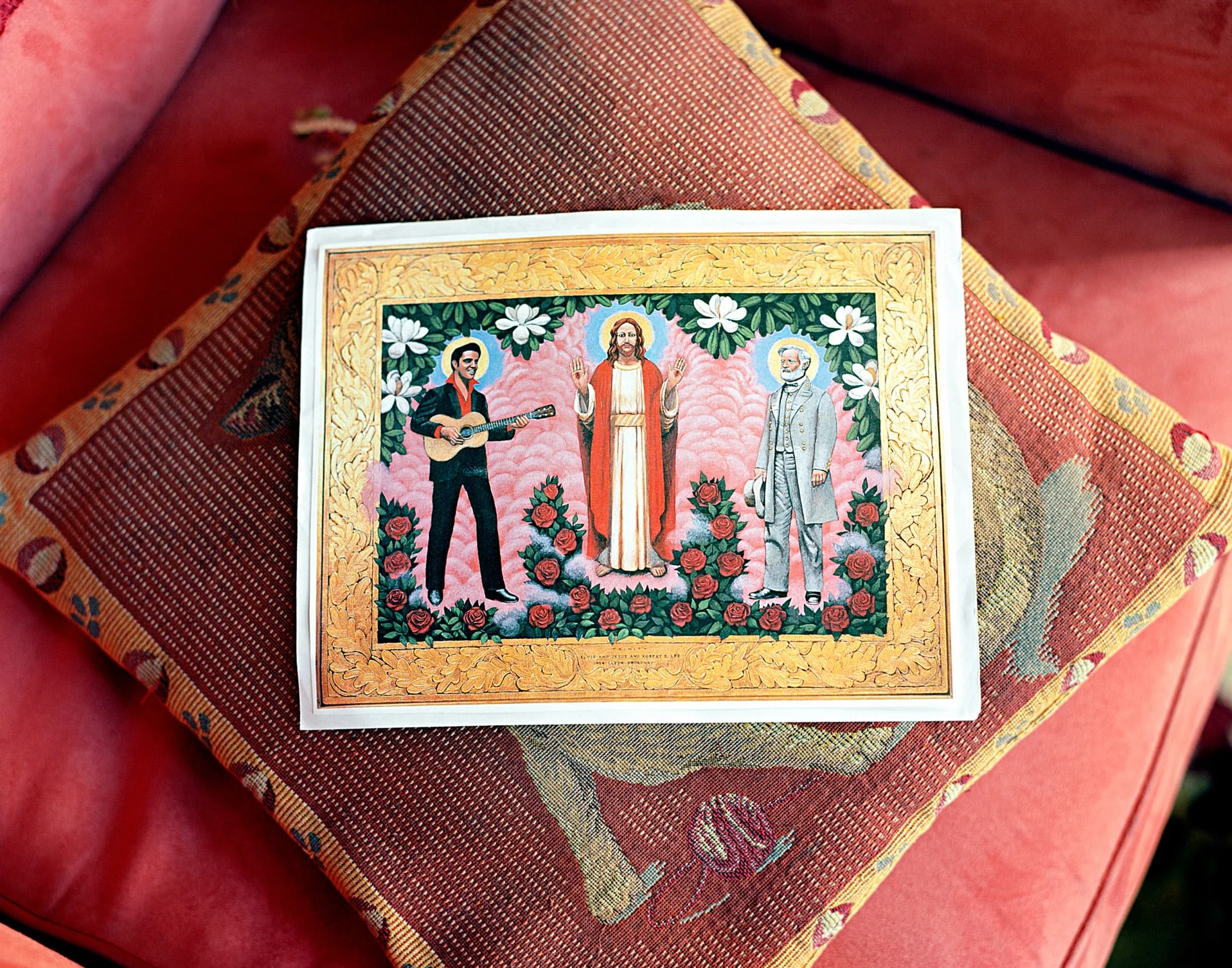

The Southern Trinity

I photographed a copy of artist Clyde Broadway's “Trinity — Elvis and Jesus and Robert E. Lee” at the home of Dr. Stephen Davis, author of “What the Yankees Did to Us” and “Atlanta Will Fall.” During our interview, Davis remarked, “To be a Southerner is to be, in my opinion, unlike any other person from a region because of our peculiar history. Our history, the legacy of slavery, the legacy of starting a Civil War for independence, and having lost that Civil War, are defining elements of white Southernness. I'm speaking as a white southern male for whom the Civil War, the Confederate War for Independence, is the defining element of my regional identity. It cannot be effaced. Blacks and whites can differ about the legacy of the war, we can differ about the meaning of the war, but the war won't go away."

Lee’s Birthday Celebration

Milledgeville, Georgia

Two young boys look on as Confederate reenactors assemble for the annual Robert E. Lee Birthday Parade in Milledgeville, Georgia. Lee's birthday is designated a state holiday in Alabama and Mississippi. Both states’ official records designate the third Monday in January as celebrations of both Lee’s birthday and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s.

Burger Chick

Tallapoosa, Georgia

Burger Chick in Tallapoosa, Georgia, is the weekend hang for local regulars and high school students. Haralson County High School in Tallapoosa boasts of being home to the "Rebels and Rebelettes" and even has the Confederate battle flag painted on the high school gymnasium. In September 2000, someone painted over the flag, and the student body voted 861 to 150 to have it restored to its original condition. The margin of victory shocked me.

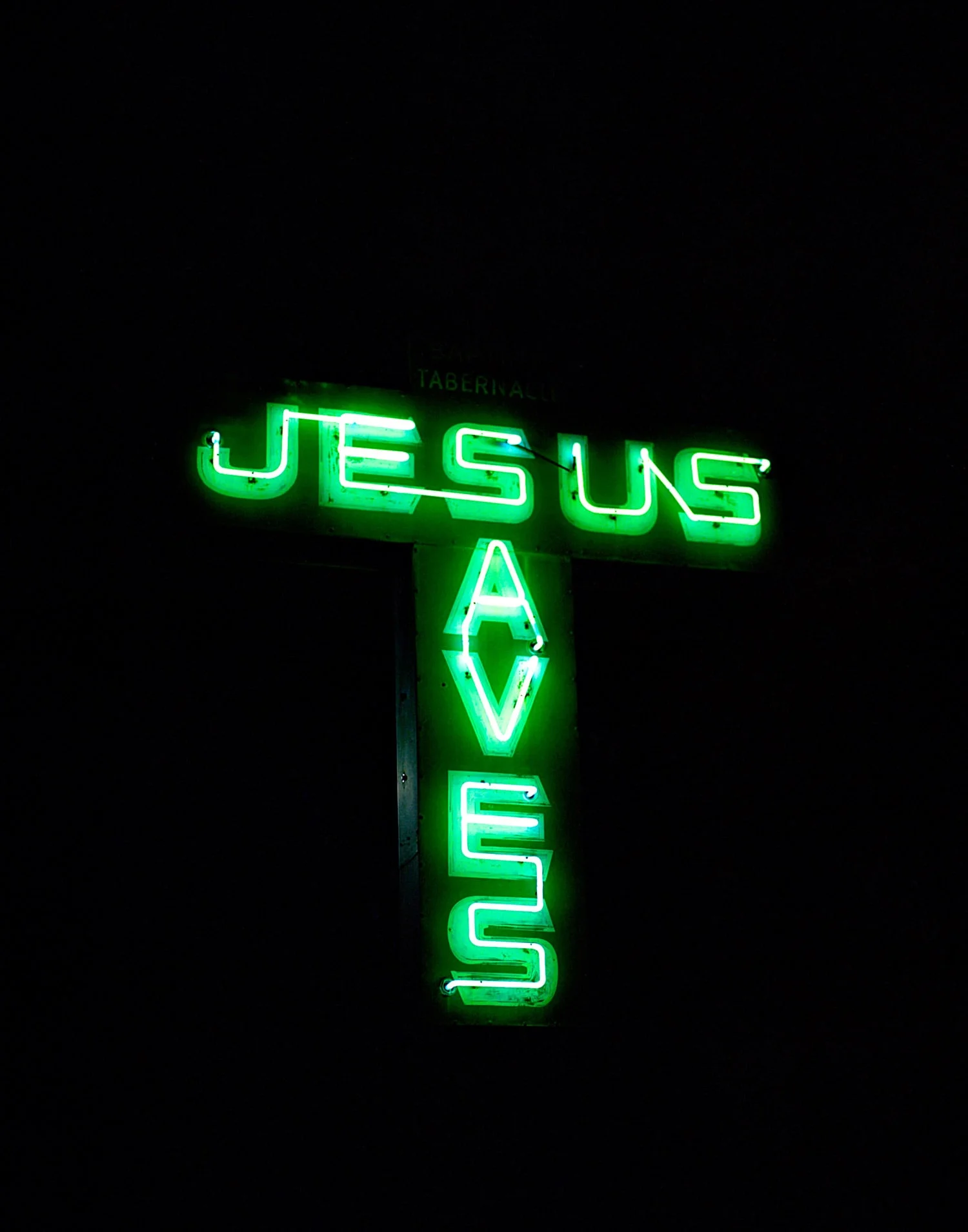

Jesus Saves Baptist Tabernacle

Nicholson, Georgia

A neon cross glows just outside the doors of the Jesus Saves Baptist Tabernacle in Nicholson, Georgia. I originally travelled to Nicholson to photograph what was, at that time, the most recently erected Confederate monument in the state but detoured abruptly after driving by the gleaming "Jesus Saves" cross up on the hill above the highway. Come to find out, I'm not the only who's made the turn. As I was welcomed inside the church by Pastor Samuel Dorsey, he told me about the numerous cases of sad and desperate truckers whom he's found outside the doors of his church, brought to their knees under that refulgent symbol of life and death. By blessing or happenstance, I shared a pew that evening with a middle-aged Southern reenactor who portrays the Union Army Commanding Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman.

Michele Green

Stone Mountain, Georgia

Michele Green sat far from the protests and fights during a "pro-white" Confederate Rally held just before Confederate Memorial Day at Stone Mountain Park in April 2016. She said, "There is no pure white race that exists. They've used symbolism to intimidate and infuriate us, but at the end of the day, it's just a flag. If you know the history of the flag, you know it was the state flag of Georgia. It represents slavery to black people in the South, but that's why I embrace it, because I never want to forget my past. I never want to forget what they did to us — how they wrapped us in that flag and lynched us as strange fruit from the trees. I never want to forget that."

Captain Bill Watkins

Ashville, Alabama

"The Confederate Rose, when it blooms, it blooms white for the purity of the South. Then the next day it turns pink for the sufferin' of the South. Then it turns blood red for the blood that was shed during the War Between the States."

— Captain Bill Watkins, SCV Commander, St. Clair Camp 308, Ashville, Alabama.

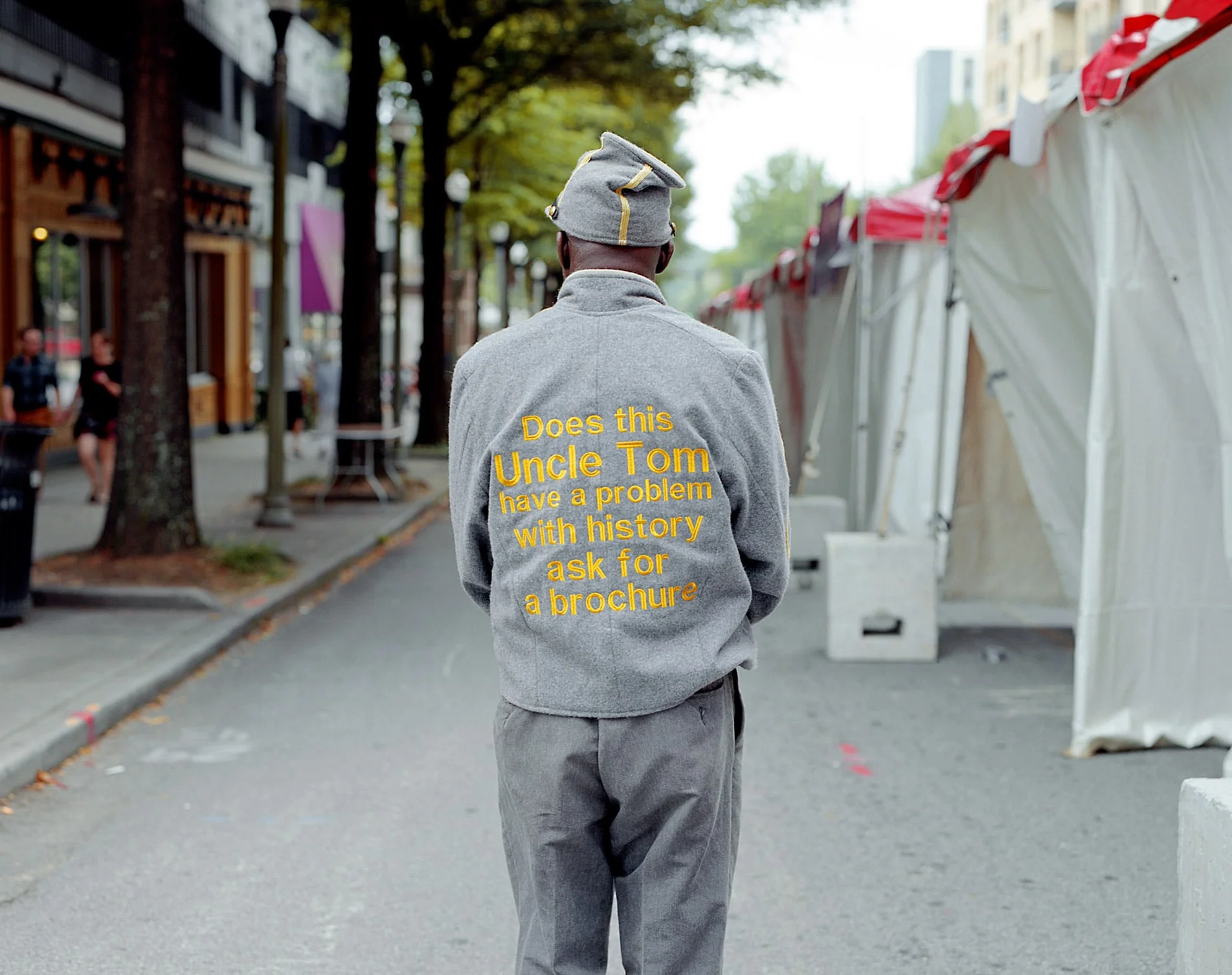

H.K. Edgerton

Defuniak Springs, Florida

H.K. Edgerton stands outside the courthouse in Defuniak Springs, Florida, during a Confederate rally held along his Southern Cross Revival March. The Southern Poverty Law Center labels Edgerton as a "black Neo-Confederate" and describes him as an apologist for slavery. Oddly enough, Edgerton formerly served as the president of the Asheville, North Carolina, branch of the NAACP but was later suspended for non-compliance after his branch fell into debt. Edgerton's appeal to white southerners is uncanny, and the SPLC provides an apt description:

"In a lily-white movement that most blacks find deeply offensive, Edgerton seems to feel quite at home. And as he dances to the tune of ‘Dixie’ — sometimes quite literally — he helps gives the cause the appearance of legitimacy."

J.R. Hardman

Reenactress

Most groups taking part in Civil War reenactments don't allow women to perform in battle. J.R. Hardman found that out after being denied permission to join her first Civil War reenactment group. She was instead prompted to join up with the other civilian women wearing hoop skirts and frilly bonnets on the sidelines. Hardman refused to be relegated to the sidelines of the battle field and has since performed a military impression at every event she has participated in throughout her time as a Civil War reenactor. Hardman's documentary film, "Reenactress,” seeks to document the lives of female reenactors who dress in male costume to portray soldiers in the Civil War. The film also brings to light that an estimated 400-1,000 soldiers in the Civil War were actually women disguised as men.

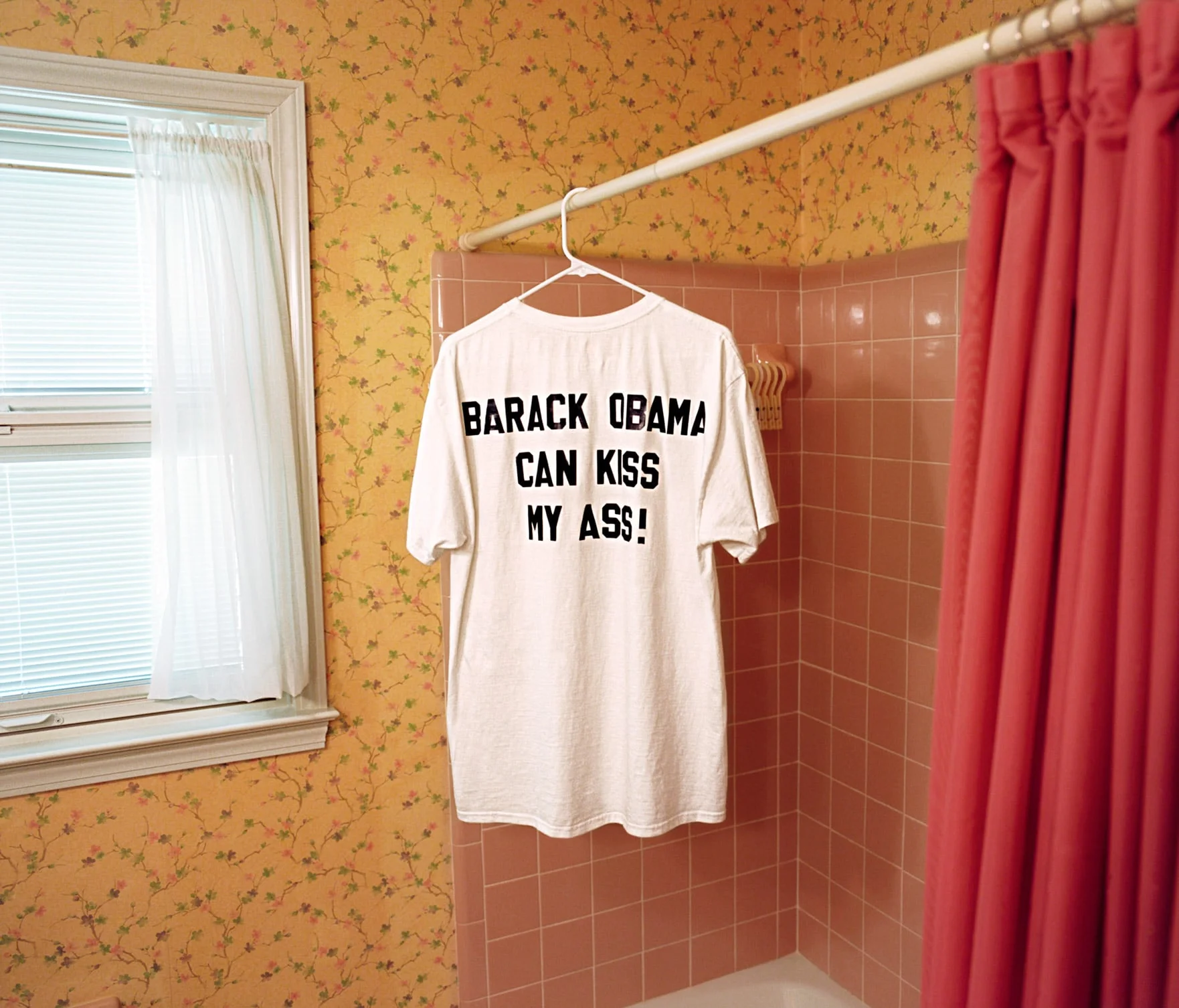

Dennis' Shirt

Smoke Rise, Georgia

Inside the bathroom of Dennis Elm hangs one of his T-shirt designs. Elm is the quartermaster of SCV Confederate Memorial Camp 1432 and an avid collector of Confederate memorabilia and assorted rarities. In his retirement, he sells handmade T-shirts as well as posters and reproduction prints depicting the Civil War at local SCV meetings and flag rallies.

Lucy Wilkins

Lexington, Virginia

Lucy Wilkins, director of Lee Chapel & Museum in Lexington, Virginia. In the summer of 2014, Washington and Lee University removed all Confederate flags from the historic Chapel due to complaints from a group of black law students. The local Sons of Confederate Veterans Camp was denied access to the facility for their annual Lee-Jackson Day celebration, a tradition at the school that dates back to 1889. Wilkins described to me the uncomfortable mix of emotions involved in the situation, and then resumed her duties as tour guide for the rest of the afternoon.

The Breedlove Sisters

Lexington, Virginia

The Breedlove sisters, Sheila and Susie. The Breedlove property once belonged to Confederate Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, as part of a 13-acre farm he owned in Lexington, Virginia, during the 1860s.

Lee's Chapel

Lexington, Virginia

On August 6, 2014, the Confederate flags were removed from Lee's Chapel in Lexington, Virginia. This statue, “Recumbent Lee,” depicts the general asleep on the battlefield. He shows no sign of concern as the world around him continues to choose sides.