My Black Grandpa

/South Bend, Indiana

By David E. Phillips

I’m not necessarily going to tell this the way it happened. Nearly 35 years have gone by and while the jogging of my memory has returned on the investment, I can’t say if every little thing came about the way I recall, or in what order the events may have arrived. So, I’m going to tell this the way I remember it.

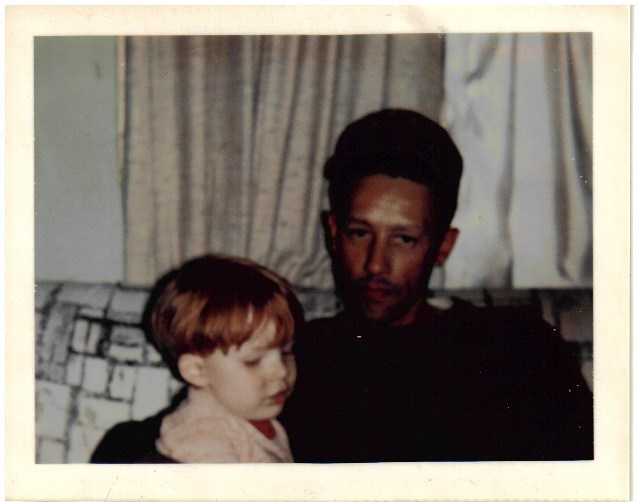

I was once the child in the photograph to the left. As you can see, I am the whitest of white. A red-headed boy from the south of Irish descent. I was born in the tiny coal mining town of Pikeville, Kentucky, in 1970. A place you probably haven’t heard of, unless you are a big fan of Dwight Yoakam (our greatest export), or steeped in the history of the Hatfields and McCoys, who exchanged gunfire and other pleasantries for years in and around the town of my birth.

My skin is beyond fair. Any outdoor activity I partake in requires great consideration beforehand. A baseball cap and Coppertone 100 are a must. The lotion must be reapplied every two to three hours, or I will surely go up in flames. If the outing is long enough, I will have poured so much of that smelly substance on my flesh that I may take on the appearance of a glazed doughnut and the aroma of a surf shop. Folks, I am white.

From 1970 to 1979, my grandpa was not.

Although not a drop of his blood courses through my veins, he is the only real grandpa I’ve ever had. My biological on my mother’s side died of the scourge known as “black lung” that so many coal miners suffered from. My father’s side has never been present a day in my life. When my grandmother remarried, she chose a charming man. Well built, strong, confident, and black — which is remarkable to me.

Let’s think on this. In the very white Southern state of Kentucky in 1970, my grandmother married a black man. I can’t even imagine what that must have been like for them. I suppose it’s possible that he was light-skinned enough to pass as something other than an African-American. The two photos I’ve shared here makes clear there was a strong Caucasian strain in his ancestry.

Interestingly enough, no one ever told me he was black. I must have wondered at some point, though, because I remember being told he was not black, that his darker complexion came from working outside. As a child, I took this at face value and never questioned it again. To be honest, why would I care? You see, when he and I were together, you could barely squeeze a dime between us. From the moment he got home from work, until the time we went to sleep, we were together. We never seemed to tire of each other. That was the first four years of my life.

After I turned 4, my mother decided she didn’t want her son to grow up in a town where so little awaited him as an adult. We moved north to Michigan and settled in the small town of Niles, just north of South Bend, Indiana, and the University of Notre Dame. There, she met a man and remarried. It’s a shame he didn’t turn out to be a better person. My stepfather was ill-tempered, and his temper when mixed with drink became toxic and, worse yet, violent.

We would return to Kentucky every summer for vacation. When we did, I could not have been happier. I’m uncertain if I knew my grandpa’s name for a long time. To me, he was just my “grandpa in Kentucky.” I loved my grandmother and my uncles, but when we pulled up that dirt driveway and parked in front of that rustic, ramshackle home at the top of that hill, it was my grandpa I wanted to see. The feeling was mutual. I also sensed he felt a need to make up for something. He used to tell me to call him “daddy.” He knew I didn’t have one. I was never able to do so. Not because I didn’t want to, but because “grandpa” had simply stuck.

From the first time I opened my eyes until the age of 13, he and my Uncle Joe were the only positive male role models in my life. I was a weird little kid — an only child who could lose himself for hours in comic books or just my own imagination. I never felt strange or unsafe with him, though. I was always on his lap or holding his hand. Those were good days for a kid with an absentee biological father and a mean-spirited drunk as a step.

He was not a perfect man. I know not what demons bedeviled him, but I know he had an angry streak that could erupt suddenly. I never saw it, but I’ve heard the stories, and they break my heart. When I was 8, one of those fits of rage resulted in him laying hands on my grandmother, who, quite reasonably, divorced him. It’s odd, but even after I learned of their split, I never expected not to see him again. As it turned out, the next summer, we ran into him while we were shopping in what then settled for a “downtown” in Pikeville. We stopped for a chat and then walked over to his humble but sufficient apartment. He was quieter than usual. Affectionate to a degree, but more politely so. It’s possible he understood something the 9-year-old in front of him did not: that this might be the last time he saw me. Best not to get too close.

Had I known at the time I would never see him again, I would have been inconsolable. I guess when you’re living in the moment, you always think you’ll have more of them.

After that chance encounter, he moved on, and the distance in miles and familial connection resulted in no further contact. Then, when I was 13, I learned he had died of a heart attack. This seemed impossible to me. When I was in his presence, he always seemed a giant. Giants don’t die, right? Four years later, I was randomly thinking about him, and I recalled something in particular. He was almost never without a cap on his head, but I remembered being on his lap once when he took it off, adjusted it, and put it back on. His hair was kinky. It came to me in a rush. I turned to my mom and said, “Grandpa in Kentucky was black, wasn’t he?” My mother paused and said, “Yes.”

It’s a funny thing, isn’t it? All the grown-ups around me when I knew him were worried about the black/white stigma. Once I knew, I cared as little on a personal level as one possibly could. That isn’t to say I wasn’t fascinated by the fact of it. It was no small thing to be in an interracial marriage in the South in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement. My grandmother eventually moved from Kentucky to live with my parents after her third husband died. I often thought of asking her questions about my grandpa, but knowing how badly things ended, I was afraid to bring it up. Not for her so much, but for me. I don’t think I wanted to hear about any other flaws he surely had, or any sadnesses they experienced. That was a mistake. My grandmother died a little over a year later, and those questions will forever remain unanswered. If there’s a lesson there, it’s while you have your people around, find out all you can. You will thank yourself later.

Still, I know enough. I know that when I was with him, I was seldom happier. He was kind to me. He loved me. I’m a little more open and capable of kindness myself because of him. That will have to do. It’s a strange thing to have someone be in your life for such a relatively short duration, yet have so much effect you. I don’t have a lot from my time with my him. Just the scattershot memories of personal folklore and those two photographs. It counts for more than you can possibly imagine.

His name was David Mullins. He was my grandpa in Kentucky. He is remembered.