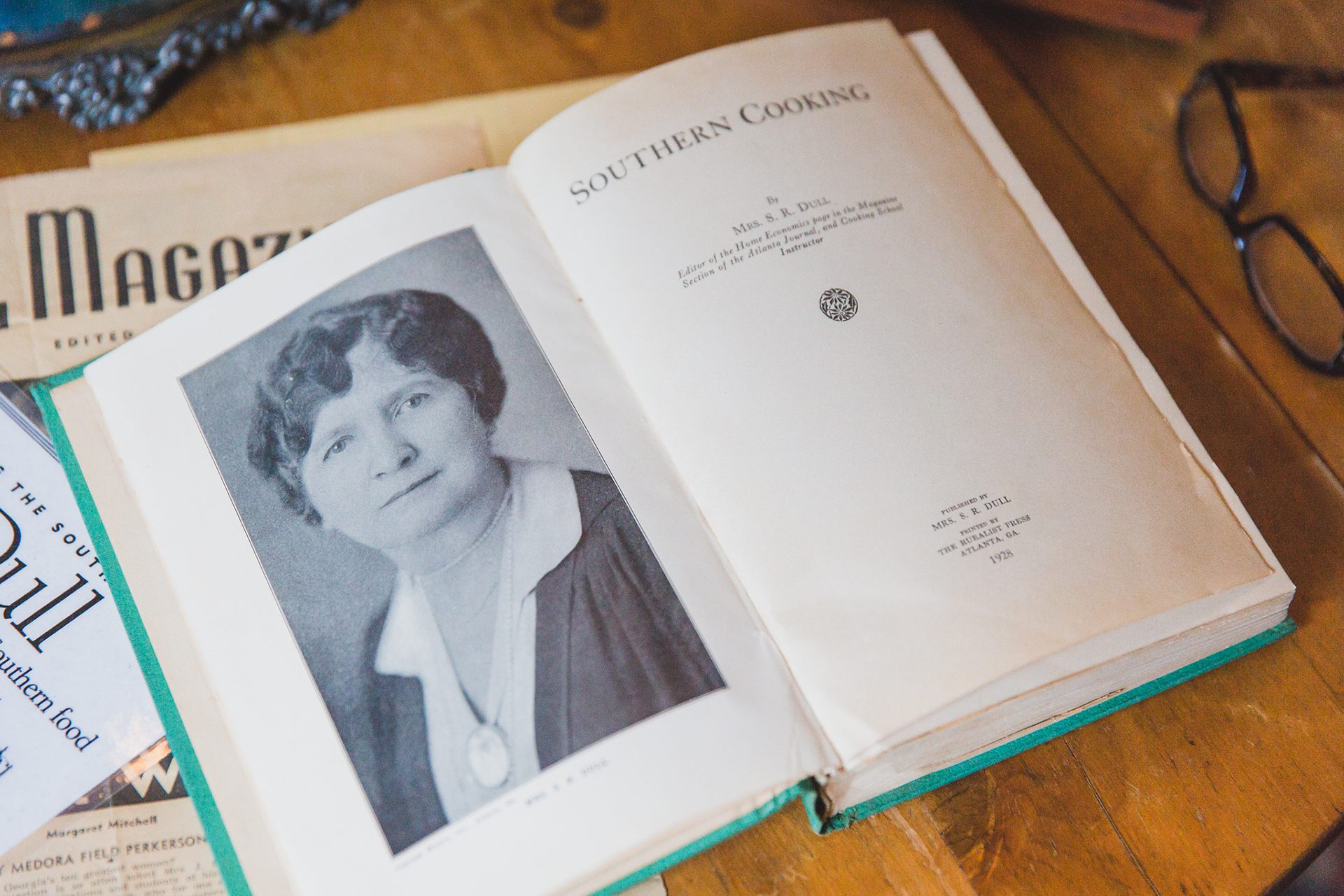

Henrietta Dull in 1928 published a simple volume called “Southern Cooking” that wound up having a profound influence on the world’s understanding of the way Southerners eat. Today, food writer Anne Byrn visits with Mrs. Dull’s 95-year-old granddaughter and digs back into the history of the woman who taught the South to cook with gas.

By Anne Byrn | Photographs by Brian Smith

My fascination with Mrs. S.R. Dull began on May 15, 1978, the day I arrived at the Atlanta Journal on Marietta Street as the new food writer. Everyone knew of Mrs. Dull but me. I was young and fresh out of the University of Georgia, raised in Tennessee to a mother who didn't use cookbooks or pay much attention to what other people were cooking.

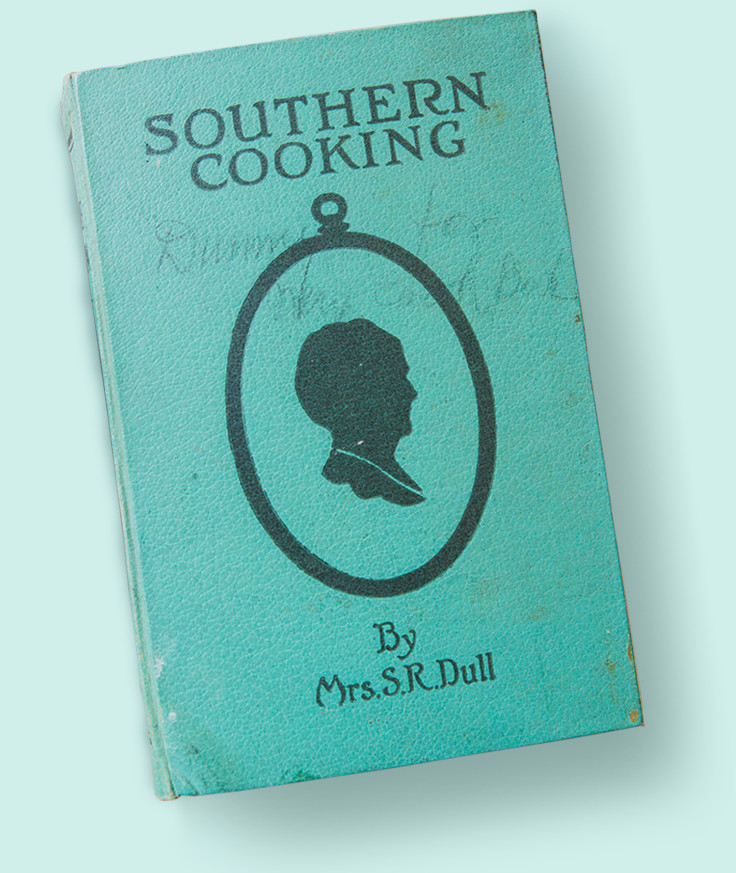

And it's probably a good thing I didn't know I was following the famous newspaper food writers Mrs. Dull or Grace Hartley when I walked out of the elevator into the sixth-floor newsroom. I was 22 and had fried chicken only once, with my mother’s help. Mrs. Dull not only fried chicken with ease, but she also told the world about it and all our other Southern recipes in her 1928 landmark book called “Southern Cooking,” the intimate and instructional cookbook that defined what was Southern food.

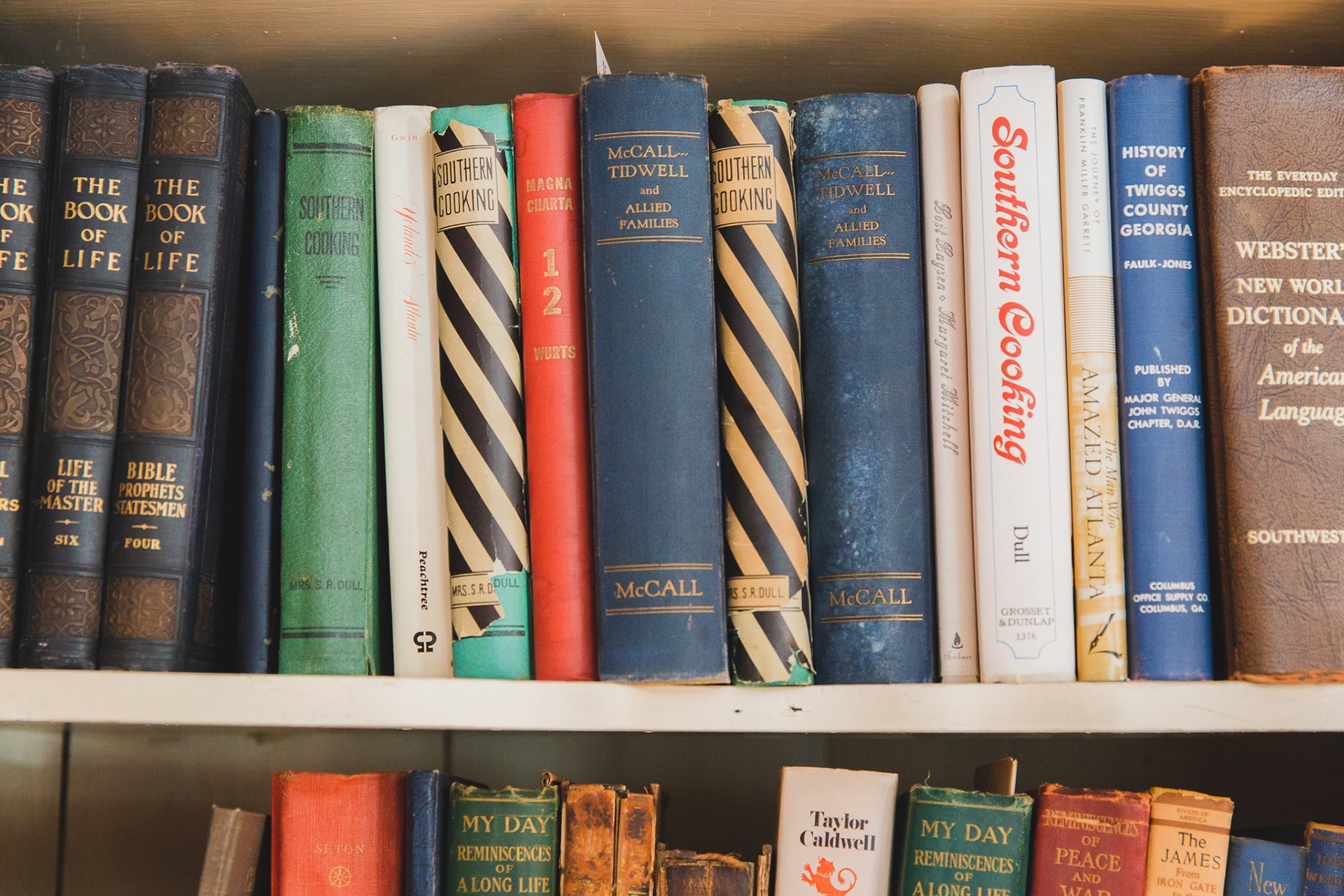

Once I left the newspaper in 1993, Mrs. Dull's cookbook, in which I had gently scribbled suggestions and additions to her classic recipes like Japanese Fruitcake, Lane Cake and Angel Food Cake, came with me. It has been a longtime friend, a steady counsel, a point of reference and remains on my Nashville bookshelf today.

Mary Frances Woodside sits on the sofa of her quiet Atlanta townhouse. At 95, Mary Frances reflects on her famous grandmother as if it were yesterday, when “Sis Hennie” was teaching her how to crochet a dress, on vacation down in Indian Springs. Or, when they were in Sis Hennie's "experimental" kitchen making dogwood petals out of icing and frying flour-dredged chicken in an iron skillet, timing it to cook 30 minutes on each side.

And when her grandmother's book, “Southern Cooking,” was first published in 1928, and Mary Frances was 7 years old, a fudge recipe in that book was named after her. Years have passed, and generations have come and gone. But what remains with Mary Frances are fresh, uncluttered memories of her grandmother, Henrietta Stanley Dull, aka Mrs. S.R. Dull — the Atlanta newspaper food columnist, author, Southern cooking teacher and celebrity.

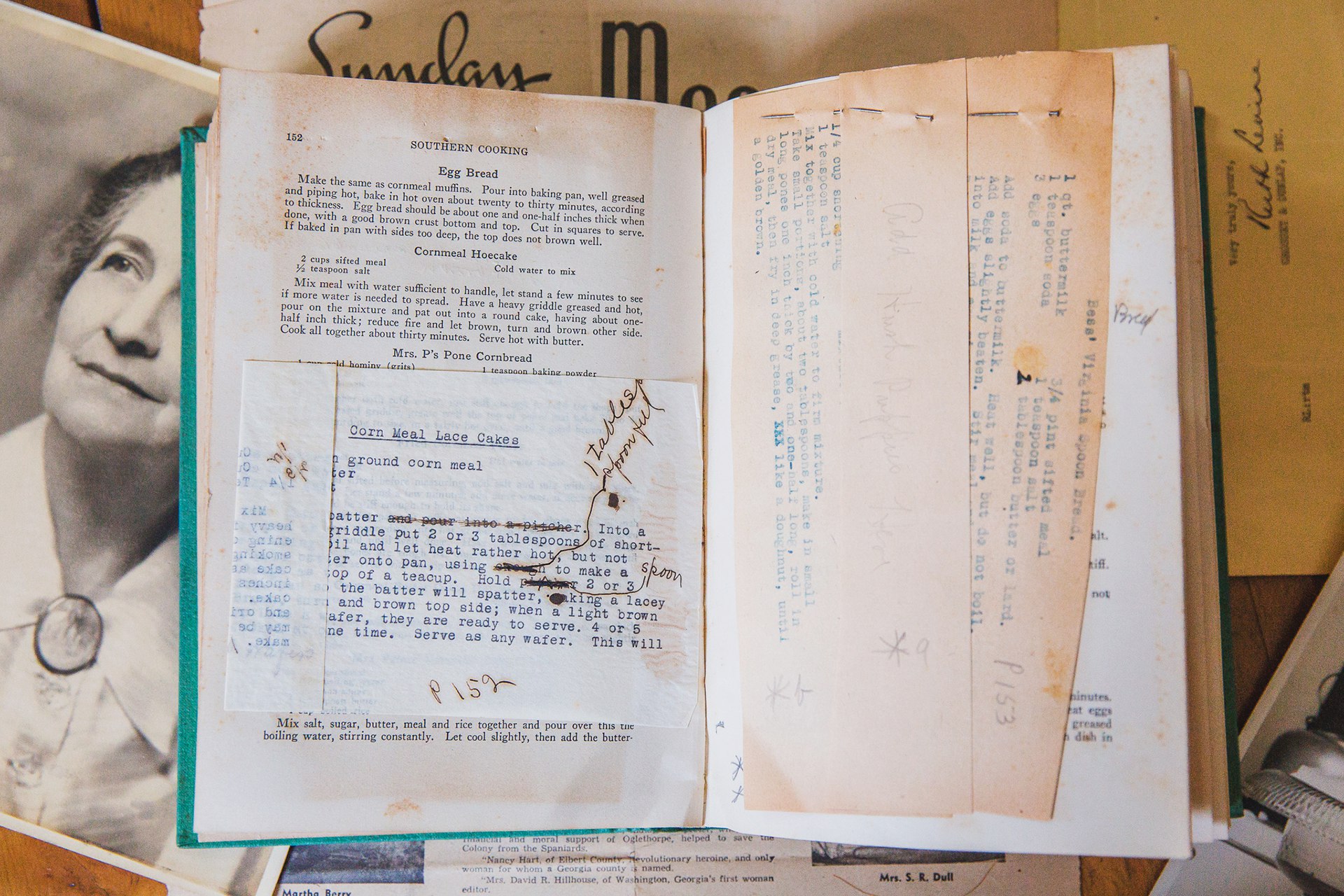

Mary Frances, one of seven grandchildren, is now the keeper of the treasures of Henrietta's life, from photos with Walt Disney to handwritten notes attached with straight pins to first-edition pages of “Southern Cooking.” Open a scrapbook and Mary Frances dials back time, telling stories of white gloves, tomato aspic and Atlanta debutante parties, of Sis Hennie's Japanese Fruitcake on the sideboard at Christmas, of crisp corn pone at supper. And of war rationing, wringing a chicken's neck, beating egg whites by hand for angel-food cake, and the knowledge that before Sis Hennie was famous, she sold food to the ladies at First Baptist Church to support her family.

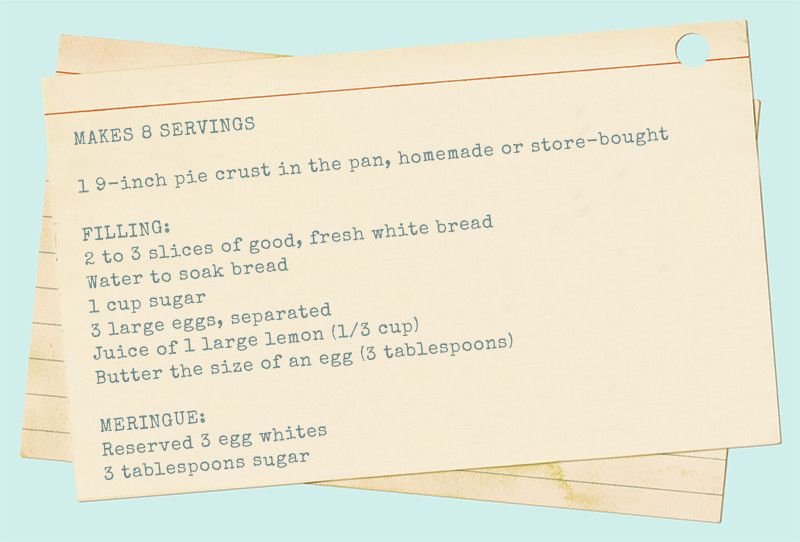

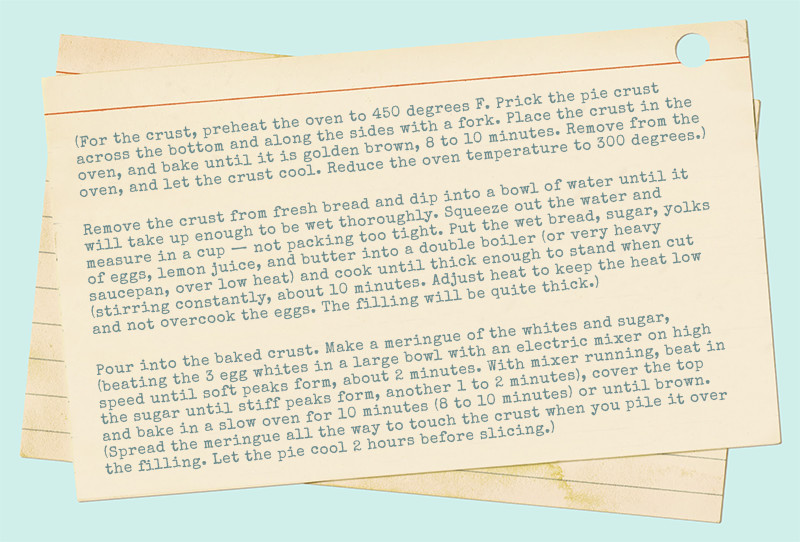

(NOTE: This recipe is said to have come from the old Blue Ridge Hotel in Clayton, Georgia, where Mrs. Dull spent time during the summer. The hotel, built in 1858 and open for 90 years, was known for its good food and was a favorite stop for locals, traveling salesmen and tourists who came in via the railroad. The pie is unique in that the lemon filling is thickened by softened bread instead of cornstarch or flour. Mrs. Dull's method might seem vague by today's standards, instructing you to brown the meringue in a slow oven [300 degrees], use "butter the size of an egg" [3 tablespoons] and the juice of one large lemon [1/3 cup]. She was writing for cooks who baked in the pre-thermostat era in everything from wood, to coal, to eventually gas and electricity. I have added modern steps — how to brown the crust, precise oven temperatures, etc. — but tried to leave the recipe in the voice of Mrs. Dull. The pie is delicious, made from ingredients found in most every kitchen any time of the year. — Anne Byrn)

In the early 1900s, in Atlanta and other big cities around the South, gas ranges came to the rescue of cooks weary from the sooty drudgery of coal- and wood-fired stoves. The sleek, clean enameled surfaces and graceful legs of these new gas ranges brought a change to kitchen design, as well as recipes. And compared to the behemoth wood-fired stoves, the smaller, faster-to-heat gas ranges fit well into new bungalow homes.

But gas was a misunderstood fuel. While it was popular in England, it took a little getting used to in America. Especially in the South.

"When gas first came out," says Mary Frances, "women were afraid of it." Early gas ranges came without pilot lights — you lit them with a match or a long, rolled-up piece of newspaper. And if you accidentally left the gas on after cooking, the gas could fill the oven and the kitchen, and the slightest spark, even from turning on a room light, might cause an explosion. The ranges got safer, of course, with electronic ignition on burners and concealed pilot lights, but fear remained.

Atlanta Gas Light, a company founded to fuel the city's streetlights and make Atlanta a safer place to travel at night, had a public-relations challenge on its hands with the new gas stoves in 1910. The gas company’s bulletins advised salespeople how to overcome the "superstitious" customer. No one was really comfortable cooking with gas until Mrs. Dull, a caterer and cooking teacher, went into homes and baked angel food cakes and all the Southern delicacies using gas heat.

“A cookstove is like a new husband,” Mrs. Dull told the young ladies. “You have to live with it and learn to get the best out of it.”

The voice of reason, a quiet and stern assurance, Mrs. Dull was the South's Fannie Farmer.

"And the gas company gave her a new stove for years and years," Mary Frances adds, with a smile. "I got her used ovens after I got married."

Henrietta Celeste Stanley was born in the 19th century, on Dec. 7, 1863, during the Civil War. She was one of five daughters and three sons and raised at a time when eggs were freshly laid, corn meal was milled locally, and you killed and cleaned the chicken before you fried it. Her home was Stanley's Mill, now Chappell's Mill, a plantation in the northernmost part of Laurens County, Georgia, near Brunswick, according to local historian Scott Thompson. Her father's family, the Stanleys, were fourth-generation millers originally from the St. James River area in Virginia. Young Henrietta spent a lot of time in the kitchen, fascinated with cooking.

But with the slow economic recovery in the South after the war, Henrietta's father moved the family north to the Atlanta area so he could work for the railroad. There, in 1886, Henrietta met and married Samuel Rice Dull, a Virginia widower and father of one daughter, says Mary Frances. The Dulls would have five children of their own. Sam worked for Southern Railway. All was well until he suffered a nervous breakdown.

"He stayed in bed. He couldn't go to work,” Mary Frances recalls, staring out the front window. “My grandmother was forced with this dilemma of supporting her family, so she went to her church, First Baptist, at the corner of Fifth and Peachtree, where she was a charter member, and told them she would make cakes and sell them to the members. … She made sandwiches, and one thing led to another and she had a catering business on her hands. She was known for her cakes, her cheese straws and her tomato aspic."

When Grace Hartley, who succeeded Mrs. Dull as Atlanta Journal food editor, interviewed her in 1961, Mrs. Dull reflected on that hard time in her life and said that the only thing she knew how to do as a young mother was cook. It was common for women to prepare their own fruitcake batter and take it to a bakery to have it baked. So Mrs. Dull offered to make the fruitcake batter for the church women.

"Soon church folks and neighbors were asking for other cookery services and more information about good food, and she found herself in the cooking-school business,” writes Grace Hartley. “She kept no record of the number of schools she held in the South — but they added up to hundreds, and whenever she went she always demonstrated before a packed house.”

After the turn of the 20th century, better home appliances, new ingredients like baking powder and bleached flour, as well as an interest in science and nutrition contributed to a change in the way food was prepared. These new tastes in foods offered cooking schools in Philadelphia and Boston an opportunity to teach women how to cook and turn this skill into a profession, or for the wealthy, to manage a household staff. In the South, there were no cooking schools of this scale, but smaller cooking schools and programs were offered by gas utilities, newspapers and food companies to expose the home cook to new ideas and ingredients. Impressed with her celebrity and her knowledge of cooking, Atlanta Gas Light hired Mrs. Dull to coax Southern women into cooking with gas.

Henrietta Dull’s background — smart, hard-working, someone who had experienced hard times and was the breadwinner for her family — prepared her to go into homes and be well received. She cooked for soldiers during World War I at a recreation house in Atlanta because two of her sons were serving in the military. She could relate to all demographics of Southern cooks and assure them it was safe to cook with gas, or easy to make cornbread, or not too difficult to make a lemon meringue pie, set a table, get more calcium in their diets.

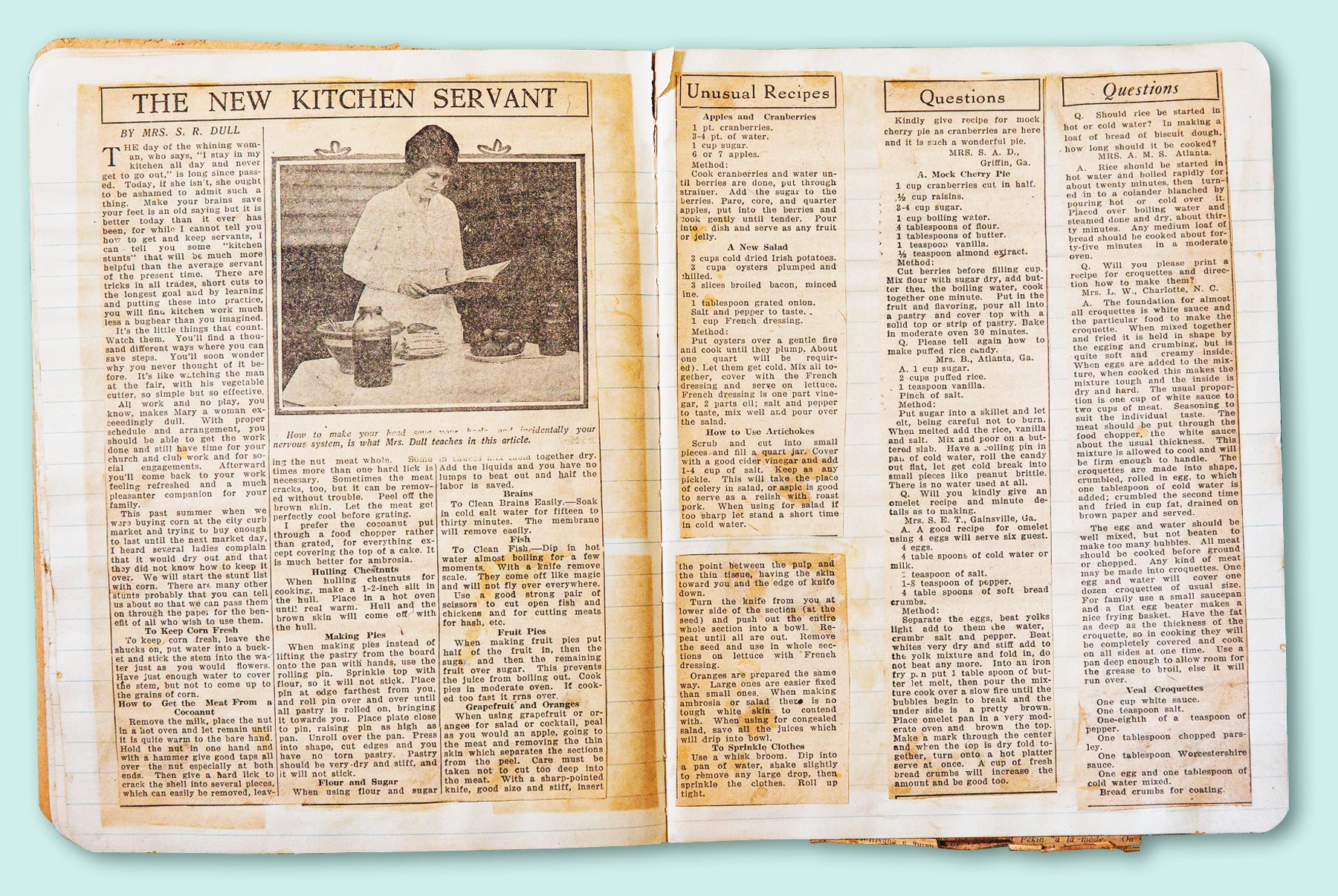

Sam Dull died in 1919. And one year later, Mrs. Dull approached the Atlanta Journal, asking to write a cooking column offering advice to new cooks. It was called “Mrs. Dull’s Cooking Lessons,” and that column lasted 20 years.

Her experimental kitchen, where all recipes were tested, was on Cumberland Road in northeast Atlanta’s Morningside neighborhood, and Mary Frances remembers that the kitchen was never remodeled. She recalls that her grandmother struggled with writing in the beginning, so the newspaper teamed her up with a younger writer — specifically, one Margaret (Peggy) Mitchell — for some help. The ladies became friends and were members of the Atlanta Quota Club for authors.

Just as Fannie Farmer and other teachers in the North were standardizing cup-size measurements, Mrs. Dull “taught the South how to measure,” says Mary Frances. But in her own way. She defined oven temperature as “slow,” or “moderate,” or “hot,” so that cooks with all types of ovens, not just those with the fancy new thermostats, might cook along with her. She alternated efficient teaspoons and tablespoons with colloquialisms like “butter the size of an egg.” Her recipes excluded no one, and the public loved her. Food companies White Lily and Merita Bread took notice and paid her to endorse their products.

"The Georgia Department of Agriculture sent her to New York and paid all her expenses for creating peanut and sweet potato recipes,” Mary Frances adds. “A lot of people knew who she was.”

And her family couldn’t have been prouder. Mary Frances shows the photo with Walt Disney and tells how famous New York milliner G. Howard Hodge sent Henrietta a new hat each season for free. “She and Mr. Rich (of Rich’s department store) were good friends.”

Grandmother Sis Hennie learned how to use her influence. In 1922, Mrs. Dull noticed schoolgirls who didn't know how to cook or do any domestic work, things she thought imperative to a productive life. Unable to convince the school board to start a much-needed home economics program, she took aside a half dozen girls, taught them how to cook a simple dinner, and then invited the school board over to her home. After the board complimented Mrs. Dull profusely on the delicious meal, she brought out the students who had prepared it from her instruction. The board was convinced, and home economics was offered in Atlanta schools.

But possibly the greatest contribution from Mrs. Dull was her cookbook, a primer to cooking Southern food in the 20th century, printed by Ruralist Press. Before modern refrigeration and with few if any store-bought conveniences, there were no leftovers. Women prepared three meals a day and didn’t have the time to write down recipes. Mrs. Dull, with one foot in the plantations of the 19th century and one foot in a modern, new Atlanta, offered them the only cookbook they would ever need. And while her husband’s initials created the South’s most famous cookbook byline, it was Henrietta Stanley herself who cooked recipes of her childhood by memory, interviewed cooks and shared their recipes, and offered cooking advice so others could follow. It was dedicated to: “My Friends, the Women of Atlanta, of Georgia, and of the South.”

For today’s cook, turning the pages of “Southern Cooking” is a wonderful throwback to how the South used to cook without shortcuts. “How to dress a turkey” has nothing to do with clothing them and instead how to remove feathers, innards, feet, and prepare the bird for cooking. Recipes for possum, Brunswick stew of chicken and butterbeans, Hot Tamales, American Chop Suey, 19 recipes for oysters, sauces from barbecue to hollandaise, and croquettes of all variations — from chicken to rice to salmon to sweet potato — reveal the rich and varied recipe box uniquely belonging to the South.

In “Southern Cooking,” Mrs. Dull advocates green vegetables, milk and a clean life. She serves up salads of grapefruit slices and avocado (then called alligator pear), and she offers four alcoholic beverages under the subtitle “Southern Hospitality” - eggnog, a hot brandy drink and blackberry and scuppernong wines. Her mother's wedding cake recipe of 1860 was a new twist on pound cake for its time, containing beaten egg whites along with a little baking soda and cream of tartar for lightening the batter. Lane Cakes, Jam Cakes, Mahogany Cakes, Fruitcake, Sponge Cakes, tea cakes, gingerbread, pickled peaches, tomato catsup and chutney, damson conserve, and for the invalid — poached eggs, toast, broth — are among the countless recipes.

And Mrs. Dull isn’t short on giving out advice. Here are some of her “Thoughts about the Kitchen”:

- The woman is the heart of the home, and the kitchen is the heart of the house.

- A kitchen medium size is best because it is more easily kept, less steps being required to do the necessary work, thus saving the woman time which may be used for recreation.

- The sink should be under a window.

- A stool to sit on when preparing food is a great help and saves tired feet and nerves.

A New York publisher, Grossett & Dunlap, noticed Mrs. Dull’s strong book sales and republished the book in 1941 for a national and international audience, sending “Southern Cooking” to seven countries and selling more than 200,000 copies. Recipes were added, and the book expanded from its original size to 1,300 recipes on 400 pages. According to Mary Frances, a cousin didn't renew the copyright on that book. The 1941 book was republished by the University of Georgia Press in 2006, and Southern food writer Damon Lee Fowler wrote the introduction.

The appeal, said Fowler, was to honor Mrs. Dull, who is “one of the 20th century’s most iconic Southern food writers” who “spanned the gap between the antebellum South and the modern South of the mid-20th century, having been born as the War Between the States was beginning and lived to see the full bloom of the Civil Rights movement.”

Mrs. Dull retired from writing in 1938. She spent time with family and enjoyed gardening and sewing in her later years. She died at 100 in 1964 and is buried at Westview Cemetery in Atlanta.

Known to new brides for her legendary tomato aspic, a whiz at creating Baked Alaska for her grandchildren, Sis Hennie was all the grandmother a little girl could wish for, and then some.

“People thought she looked stern, but she had this great sense of humor. And she was never worried,” says Mary Frances. “She was just easy going about life in general. She tithed completely at First Baptist until her two sisters who ran a boarding house around 10th Street quit working. And then she said the Lord wants her to look after her two sisters instead.”

Quite a life and a legacy for a Southern girl from the white columns of Laurens County who had six children, a sick husband, and all she knew how to do was cook.

-------

Anne Byrn shares an adaptation of Mrs. Dull's Japanese Fruitcake recipe in her new cookbook, “American Cake,” which will be published Sept. 6. The cake has nothing to do with Japan but everything to do with the gussied-up, exotic-sounding layer cakes once so popular in Georgia and the South. Byrn will talk about that cake and others at Georgia’s Decatur Book Festival on September 3.