Kosher Gumbo

After a magical, musical night in the Faubourg Marigny of New Orleans in 2012, writer Rob Rushin was compelled to follow two folk musics — the jazz of New Orleans and the klezmer of Eastern European Jews — deep into their history, and then back to New Orleans, where the two lines come together in the form of skilled musicians known collectively as the Panorama Jazz Band. Join us on this journey into a weird, wonderful mashup of the South and Eastern Europe — and learn once again why the South’s greatest cultural achievements arise when we embrace each other.

NEW ORLEANS, 2012 — You’re wandering north on Frenchmen Street on a too warm autumn Saturday, the river at your back, the amateurs of Bourbon Street several blocks to the west. The residue of cubicles and spreadsheets cling like your sweaty shirt.

Frenchmen is packed with the usual assortment of trinket vendors, buskers, panhandlers and more than a fair share of Brooklynoid beardos sporting lumberjack flannel in a climate more suited to linen or seersucker. Motor traffic is just a shade brisker than standstill. People carrying go-cups drift well past the curb, the commingling of flesh and automobile a seething mass of what modern civilization looks like when polite delineations between pedestrian and driver collapse. Pedestrians take the upper hand with audacity fueled by alcohol.

You wander past clubs on the lower end of Frenchmen, resisting the enticements of The Praline Connection for now — because later you’ll be dying for that mac and cheese and fried chicken to soak up an excess (for you, maybe) of drink. And you save for later a pilgrimage to the Apple Barrel, where you’ll order up a shot and, if you’re lucky, sit on the very stool where Coco Robicheaux drank his last before he excused himself to the men’s room where he breathed his last — because New Orleans is a place of ghosts, and to pay tribute to the dearly departed is to curry favor with the spirit of the place. Even though you hold no truck for such woo-woo nonsense, you recognize that in this cradle of gris-gris and inexplicable mojo of allsorts, it’s probably better to hedge a little Pascal’s wager, to be safer than sorry just this one time. And only then will you realize that your Coco Memorial Shot will be the one that makes the inevitable sit-down at Praline so very, very necessary.

But that’s later. For now, because you’ve been hectored and badgered no end to “for chrissakes whatever you do, be sure you hit the Spotted Cat between 6 and 10 on Saturday,” you press on.

You penetrate the sidewalk scrum and enter the Cat. You sense the crowd in here is not like the one out there. You gawk at several paintings of a thin African-American man in a Treme Brass Band cap, and the guy beside you fills you in — with more than a little bit of hometown pride — that the paintings depict Uncle Lionel Batiste, one of the lions of the Social Aid and Pleasure Club scene that was the wellspring of brass-band culture. Batiste started gigging at age 11 while still a resident of the Colored Waifs Home for Boys, and is still at it almost 70 years later.

You watch a few musicians set up in the cramped window-box stage. There’s a guy unpacking a sousaphone, another with a six-string banjo. There are drums and, incredibly, an accordion, a rare sight for a New Orleans jazz band. Your first beer gone, the angst you’ve brought with you from wherever slackens, and you feel that little moment of internal “ahhhhhhh” where you let New Orleans start to inhabit you instead of the other way around. You’re glad you bought two beers. A trombone appears, and a woman fits a reed in an alto sax. Sitting amid the onstage hubbub, a very tall, very thin man sits quietly with his clarinet in his lap, exchanging a few words with the rest of the band, but mostly just smiling quietly to himself, everyone easing into the evening.

Then they unleash a blast that reminds you of a bar mitzvah you attended long ago.

The Panorama Jazz Band is smoking the klezmer classic “Oy Tate S’Iz Git,” written in the 1920s by the (first) King of Klezmer, Naftule Brandwein. It’s got the second-line drums, the pulsing swing-pah of the sousaphone, the serpentine clarinet melody, the intricate polyphonic counterpoint. It’s New Orleans music, by damn, written by an Eastern European Jewish immigrant in New York nearly a hundred years ago.

And then they jump into “Hasirei,” written during World War II by the (second) King of Klezmer, Dave Tarras, and you realize the dancers, hankies held aloft in traditional second-line style, would not look out of place at a wedding in the Catskills. A few folks send a terrified young lady skyward in a chair, and then another chairborne person arises, this second perhaps overly ambitious (the gentleman in the hot seat appears not to have skipped many meals lately) but his porters are game and keep him aloft until nearly the end of the tune, his dismount far short of Olympic standards.

Your second Abita is gone and you’re starting to feel a little fuzzy yourself. The band announces “Di Shikerer Tantz” (“The Drunkard’s Dance”), and you notice standing by the door an impeccably dressed gentleman — complete with fedora, watch chain, and matching tie and handkerchief — and you recall the paintings on the wall and realize, damn!, it’s the Uncle Lionel. In the flesh. The crowd parts — because it must be said — like the Red Sea to allow him to walk-slash-soft shoe across the room untouched. The band acknowledges his Presence and calls another tune, this one a beguine from Martinique, followed by a hora written god knows when, and then they crack out Sidney Bechet’s “Come Out Swinging,” and there’s a saxophone solo that makes you almost dizzy and you’re in New Orleans and you are dancing your ass off.

ELSEWHERE, 2016 — Tracing the origin of any music is a fool’s errand, the musicologist equivalent of Aquinas’ attempt to prove God’s existence. No matter how far back you go, you stop short of the one true source, left hanging onto some just-so parable about crossroads or noble savagery or other such fairy tales. What the hell. Let’s try anyway.

Proposed: Distinctive folk cultures typically develop under some kind of social isolation. That’s not to say that “new” musics emerge in a vacuum, but rather that group isolation binds people together in limited physical/psychic space, and the creative friction leads to some remarkable results — the music of Appalachia, the emergence of the blues in the Delta, the birth of jazz, the development of klezmer, the literature and mythology of the Icelanders. The list is endless. Communities effectively segregated from the dominant culture develop their own norms, food, myths, music. Inevitably, folk cultures infiltrate (or are stolen by) their dominant counterparts through a process that, in America at least, has created a true melting pot of cultures. (The segregations and divisions and exploitations remain, of course. Again, this ain’t no fairy tale.)

This story is about the parallel emergence — at roughly the same time, and on opposite sides of the globe — of two distinct strands of folk music. One is the product of the African-American experience, forged by slavery and ongoing institutional racism. The other is the music of the Eastern European Jewish ghettos and shtetls, formed under conditions imposed by centuries of anti-Semitism. Both traditions produced folklore — music, food, stories, dances, private linguistic codes — that carried their cultural DNA to future generations, and eventually, into the wider cultural stew. And both, despite their relative social isolation, were themselves the sum of a broader set of influences that these cultures appropriated for their own ends.

And ultimately: How did these ingredients find themselves tossed together, simmering in the gumbo pot of New Orleans music, on a cramped window stage under the banner of a band called Panorama?

A nice, simple question.

Proceed.

Everybody knows New Orleans is the birthplace of jazz, the gumbo pot that cooked up perhaps the richest and most flexible, self-regenerating music the world has ever known. Dozens of cultures found themselves on not-always firm common ground, a smattering of historical kizmet that could never be planned.

Not that jazz comes from New Orleans. Jazz (and we acknowledge that the meaning and origin of the term “jazz” is itself fraught) comes from almost too many places to be sure you’ve named them all. So maybe it’s better to say that New Orleans is where jazz came to become, the pot where the ingredients blended to make that incredible gumbo. Critic Stanley Crouch recently wrote that, “It is always good to realize that any linear interpretation of the art of jazz is completely wrong. Aesthetic reality is always omni-directional, making nothing old and nothing new.” Your Narrator agrees and understands that anything he writes from this point forward is likely to catch the back of Crouch’s grouchy hand. Fools rush in.

Within New Orleans’ specific economic and social history — largely a byproduct of human greed and lucky geography — ingredients converged in time/space where a musician like Buddy Bolden (and dozens more both remembered and lost to time) could adapt available materials to create a form that nobody had ever heard before. And that form, jazz, was flexible enough to withstand at least another century’s worth of ongoing brutal racism and cultural miscegenation.

So where does jazz come from? Like a good gumbo, probably too many ingredients are in the stew to identify them all, but any rough recipe would include African drumming and chant; European harmonic tradition; Ragtime; Spanish influences by way of the Caribbean; work and worship songs of slavery; the blues.

And the U.S. Army.

Across the U.S., community brass bands provided an outlet for amateur musicians and a point of cohesion for civic events — social music. The earliest jazz emerged from New Orleans’ crowded community brass band scene. One of the main reasons these brass bands were so pervasive boiled down to one overwhelming economic/social force — the United States Army. Jazz — like Tang, the space program, the microwave and the Internet — is yet another unintended benefit of the military’s place at the core of our national identity.

The fetish for martial music to whip up the troops and stroke the sweet spot of inchoate patriotism goes back centuries and is not peculiar to America. An army needs musicians to quicken savage breasts, and in times of war, they need a lot of them. But then conflicts end and soldiers go home, some of them inspired to teach their neighbors and form local bands.

By the Spanish-American War, military bands had adopted the latest innovations in brass instruments for one important reason: sheer volume. After this quick war ended, America found itself awash in cheap band instruments along with a military-trained group of teachers eager to spread the word. New teaching methods emerged, relying on oral transmission and variants of solfѐge instead of sight reading, similar to shape-note methods used for teaching hymns to untrained churchgoers. Publishers rushed brass and band method books to market. Spurred by a growing market, instrument makers refined their designs and the military/community band instruments we know today emerged: saxophones, slide trombones, trumpets and so on.

Some brass bands were vehicles for light social entertainments, with a focus on the popular tunes of the time. The proliferation of Salvation Army-style bands, a key element of their evangelism, is one well-known example of this style. Another strain adhered to the military roots of brass music, a strain that reached its popular pinnacle with John Philip Sousa. And then there was New Orleans, where, from a foundation of these two styles, a new approach was taking shape.

Many African-American band musicians of the time, like most folk musicians the world over, had only rudimentary musical training, with the stewpot of community providing plenty of opportunity to learn the shared creative code of the street. But not all of these musicians were untrained. Concurrent with the simmering street brew, a different musical culture developed among New Orleans’ Creoles of Color. Especially under Spanish and French colonial rule, the Creoles of Color distinguished themselves in many spheres — as doctors and lawyers, professors, professional classical musicians — but they were still subject to institutional segregation.

So they created their own institutions. Orchestras. Clinics. Schools. An opera house. Their own Social Aid societies. And to maintain their own purity — as the whites strived to maintain their purity — the CoC community stood strong against incursion from below. Their relative prosperity placed them a few rungs up the ladder from slaves and freed blacks, whom the CoC considered coarse, boorish, uneducated and uncultured. A simple brown-bag test excluded anyone with skin darker than a grocery bag from polluting the elevated lineage.

But the CoC’s relative freedom was always subject to the whims of whites, and as Reconstruction twisted into Jim Crow, the CoC were suddenly considered just as black as their uneducated, lower-class cousins. Stripped of their relative privilege, the CoC were cast into the same vast pit of subjugation and poverty as the rest of black New Orleans.

For musicians, this manifested in music of the concert hall coming to live with its poor cousins of the street. A forced wedding of trained virtuosity and sophistication to the vernacular and rhythms of the street player was a key consideration in the development of jazz. One of the notables to emerge from this mélange was the great Sidney Bechet, born too late to attend the academy, but nevertheless a beneficiary of his CoC forbearers who instilled academic discipline in his playing, even as he learned the musical patois of the New Orleans streets. The combination was electric, and Bechet rose to global fame as a composer and improviser, his style highly influential to this day.

The New Orleans jazz pioneer Sidney Bechet

Dozens of bands, many affiliated with Benevolent Aid Societies — which were themselves often neighborhood-specific organizations — competed with one another for bragging rights, and perhaps more importantly, gigs. Like brass bands everywhere, theirs was inherently social music, and this meant that (like their round-the-planet brethren, the klezmorim) survival as a musician meant delivering what the people wanted to hear.

“Marches, mazurkas, polkas, schottische, quadrille — all that was music, you see. Well, all bands played that.”

— Willie Parker, clarinetist in The Eagle Band,

Eureka Brass Band and others

Around this time, ragtime music emerged, primarily in and around St. Louis, and made its way downriver. Who was the first to bring ragtime into the gumbo? Nobody knows for sure, but this syncopated twist appears to be the click that Buddy Bolden hitched to his legendary sound and tone, establishing him as the first of many trumpet kings, a lineage that would pass — after a short period of trumpetistic infighting that would make even the medieval Popes blush — to King Oliver and, eventually, Louis Armstrong. Some point to Bolden as the “inventor” of jazz; pianist Jelly Roll Morton claimed he was the one. Neither of them are quite right; nor are they wrong.

Like the label jazz, klezmer means something both quite and not very specific. The word derives from klezmorim, Yiddish for musician. Within the Eastern European Jewish communities of Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia, Moldova, Bulgaria, Romania, Slovakia and Hungary, the klezmorim played for weddings, bar mitzvahs, holidays, and other community celebrations. Theirs was social music leavened with more than a touch of the sacred. It was the stew that sustained rituals that sometimes lasted for days or weeks. And like so many working gigsters throughout history, the klezmorim were derided as lowest-caste citizens.

Like the jazz musicians, the klezmorim used their klezmer loshn (loshn = language) that allowed them to speak openly in front of outsiders (employers especially), free to express themselves as they liked. As with lore about jazz hepcats, this private language came to be seen as just one more piece of damning evidence: What are they trying to hide, anyway?

Recurrent descriptions of klezmorim include such jazz-familiar terms as degenerate, sexual deviant, criminal, violent, dishonest. Echoing accusations thrown at jazz musicians by their own church-going neighbors, klezmorim were depicted as having turned their backs on the faith of their ancestors. And despite (or maybe because of) their essential role in the community, klezmorim were subject to the most bitter epithet an Eastern European guardian of decency could muster: Gypsy.

Klezmorim were apparently insatiable predators of wives and daughters. In Sholem Aleichem’s 1888 novel “Stempenyu,” the title character is a klezmorim who tempts a beautiful woman trapped in a Bovary-esque marriage, just another slick seducer with a violin. Isaac Bashevis Singer’s 1968 story, “The Dead Fiddler,” described the soul of a dead musician as an evil dybbuk (imagine a Yiddish "haint") who possesses a young woman and turns her to licentiousness and ruin, a fine “Reefer Madness” morality tale. Early klezmer music was predominantly string-based, with violinists typically serving as the rock stars of the day, so fiddlers caught the lion’s share of glory and abuse. These were not the guys you wanted your sister to hang around with.

Klezmorim often descended from hereditary lines similar to the great New Orleans jazz lineages like the Humphreys, the Tio clarinet dynasty, Frog Joseph and his spawn, the seemingly infinite Marsalis brood, and Big Chiefs Donald Harrison Sr. and Jr. And like these jazz guys (and for the longest time, it was guys all the way down), the klezmorim carried an aura of mystique, of magic. Because when the music seduces, all the rules scatter like smoke.

Just as jazz emerged from multiple sources, the music we call klezmer embraces Jewish cantorial melodies, mazurkas, polkas, schottische and Gypsy dances and melodies. Frequently, the klezmorim and their gigster Gypsy counterparts performed together, sharing tunes and techniques. Occasionally, they intermarried, one culture commingling with the other.

During parts of the 1800s, Jews in Eastern Europe enjoyed an unprecedented social acceptance, similar to the varying degrees of social freedom afforded to free blacks and Creoles of Color in Louisiana. The “freedoms” were limited, subject to random whims of the elite, and truly not all that broad. For a while, Jews were welcome to serve in the Czar’s army, a common path for marginalized citizens to gain at least some degree of material security. Sadly, sometimes this welcome might take the form of forced 25-year conscription.

Many of the klezmorim conscripts discovered that playing in the army band was a great way to enjoy the perks of military life without all that pesky fighting and dying. String-playing klezmorim quickly picked up brass band instruments and took their place playing inspirational tunes for those about to lose limbs and lives. They also played social affairs for the officers and whoever else was willing to pay. For many, the extra income allowed them to buy their way out of conscription. Eventually, as one Czar gave way to the next, all Jews were expelled from the army under cloud of suspicion. Whatever the reason for leaving, many took their band instruments home where the louder brass gradually upended the violin-centric ensembles.

With the turn in the Czarist wind, many of these distinct and far flung communities were “encouraged” to settle in greater concentration in urban ghettos. Similarly, blacks in post-Civil War America were given little choice about where to live. For both groups, the most visible negative outcomes of ghettoization policies were severe poverty and seriously uncomfortable population densities. On the flip side, in both New Orleans and in Europe, these policies had the effect of concentrating scattered communities in a single location where the various regional influences merged in the pot of cultural gumbo/goulash.

The period from late 1800s through World War I witnessed the great migration of Eastern European Jews to the United States. Unlike earlier Jewish immigrants to America, the destination for the overwhelming majority of these pioneers was New York. If they were lucky enough to get past the gatekeepers at Ellis Island, this group found itself again crammed into small neighborhoods and homes, the latest horde arrival of “the other” to catch the unwelcome eye of civic guardians whose mission then — like anti-immigrants today — was to play the trump card as to who really counts as American. In a sorry turn of fate, the higher castes of the Eastern European diaspora were now looked upon just as their own moralists once looked upon the klezmorim — a bunch of unkempt weirdos with strange habits.

In what was an even crueler worm turn, many descendants of earlier Jewish immigrants had by now managed considerable social and financial success via assimilation during their years in the colonies and states; their overtly ethnic distant cousins were an embarrassing echo of abandoned heritage. A long-lingering divide between earlier Western European pioneers and latecomers took root as (at least) two distinct Jewish cultures emerged; for the newly arrived Eastern Europeans, a tenacious embrace of religious tradition and Yiddish culture became a central component of their community and identity. And one aspect of this now-cherished culture was in the hands of the klezmorim.

Like the trumpet king disputes, two clarinetists vied for the title King of Klezmer. Naftule Brandwein was a Boldenesque figure: a hard-living dandy with an eye for women and a taste for drink, and ultimately, a victim of his own excesses and demons. Naftule’s playing was flamboyant, filled with fast, snaking lines, elegant filigree, and showy tricks like the krekhtsn (crying or moaning), the lakhn (laughter) and the dreydlekh (literally, turns, like a dreydl). He was, for a while in the ’20s and ’30s, the undisputed King.

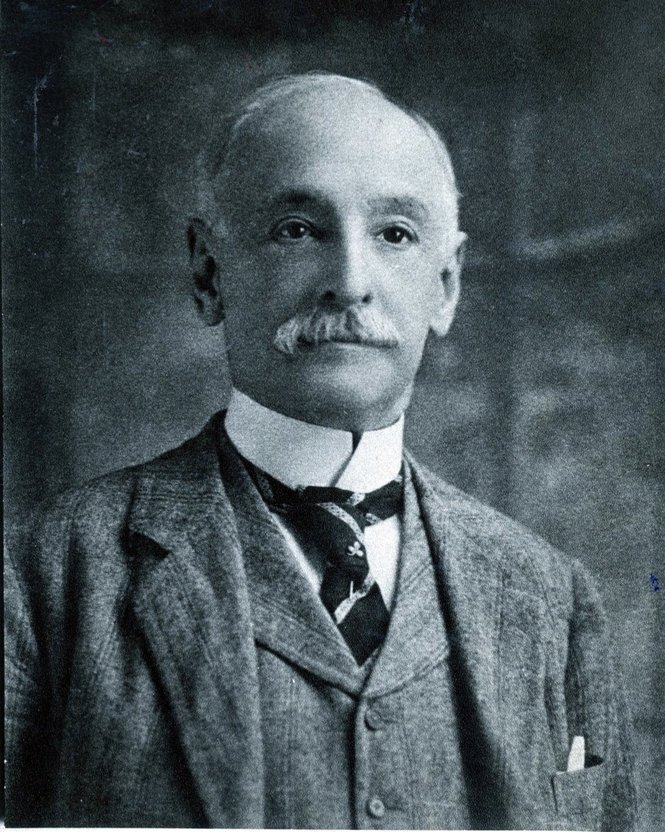

The First King of Klezmer, Naftule Brandwein

Around the time Brandwein was sinking into drunken disrepute — missing gigs, stumbling on stage, getting into fights — along comes Dave Tarras, a more refined and sober man, but no less the musician. As the increasingly unreliable Brandwein was looking down, Tarras took the crown. Long live the king.

For years, klezmorim made a solid living playing the Upstate New York resorts and the social events of the New York City area. The Yiddish theatre scene was strong, spawning hit songs like “Bei Mir Bistu Shein” for the decidedly gentile Andrews Sisters. But as the heyday of Borscht Belt/Catskills culture faded, Jewish musicians, actors and writers began absorbing — and, more often than not, creating — the American vernaculars of Broadway, Hollywood, vaudeville, radio drama and comedy. As these entertainments took hold, with the inevitable polishing of ethnic edges, klezmer began to be viewed as kitsch. Jewish culture and Yiddishisms became stock-in-trade sitcom punchlines. As Eastern Europeans became more “American,” the klezmorim once again took their place as an object of mockery and embarrassment. Dave Tarras watched the music he loved fall from grace for a few decades. Luckily, he also lived long enough to mentor a crop of young musicians determined to put klezmer back on the map.

The Second King of Klezmer, Dave Tarras

By the end of the last century, The New Yorker declared that “klezmer has become one of the primary languages of the musical avant garde.” Klezmer has run wild since the revival years of the ’70s, with scores of bands staking some claim to klezmorim status, from longtime ambassadors like the more purist and devout Andy Statman — who became a protégé of Dave Tarras in the final years of the King’s life — and the more secular Klezmatics; the Mickey Katz tributes by African-American jazz clarinetist Don Byron; and Itzhak Perlman’s “In The Fiddler’s House” project. More recently, hybrid variants like Atlanta’s 4th Ward Afro-Klezmer Orchestra, the women-only Isle of Klesbos, and our New Orleans heroes — the Panorama Jazz Band — are among scores of bands tapping into the klezmer vibe. This is the heyday of klezmer as a global cultural force. From puristas to fusionistas to avant gardistas, klezmer is as relevant as blues or bebop.

With all these ingredients traveling from far and wide to become gumbo, it’s probably fitting that all these musicians came from somewhere else to become Panorama. For better and worse, New Orleans is a vortex. Resistance is, well, ya know.

There was this 5-year-old kid living in Maryland who heard a marching band and felt himself lifted off the ground. A dozen years later, he heard klezmer, and he felt his heart leap. A few years later he heard Dr. Michael White and the Young Tuxedo Brass Band and decided to go where the air and water was made of sound. He packed his clarinet and bicycle and moved to New Orleans with $100 in his pocket. There he met a guitar player whose name was (literally) synonymous with the word klezmer. They started the New Orleans Klezmer All-Stars, and soon were touring the world to full stadiums of adoring fans. The rest is history.

Like most legends, there’s a little bit of truth in there. True: Ben Schenck moved to New Orleans with a bike and clarinet and very little money. And he did meet Jonathan Freilich (the word freilach is interchangeable with klezmer), and they did launch the All-Stars. Also true: The All-Stars did eventually tour the world playing festivals. But they did it without Ben.

The All-Stars is the first band Your Narrator can trace that blended the sounds of klezmer with the spirit of New Orleans. This group could lift a bandstand and make it spin. Over the years, they became louder and more funkified. They built a solid local following that opened doors to wider success. But the artistic vision of the two founders began to diverge, and Ben was asked to leave.

Anyone who has been sacked from a band knows the sense of devastation that goes with it. Schenck felt it, too, but had the insight to accept that the All-Stars were not the place for him. Ben had something else in mind: a band that needed no amplification and could perform anywhere at the drop of a hat.

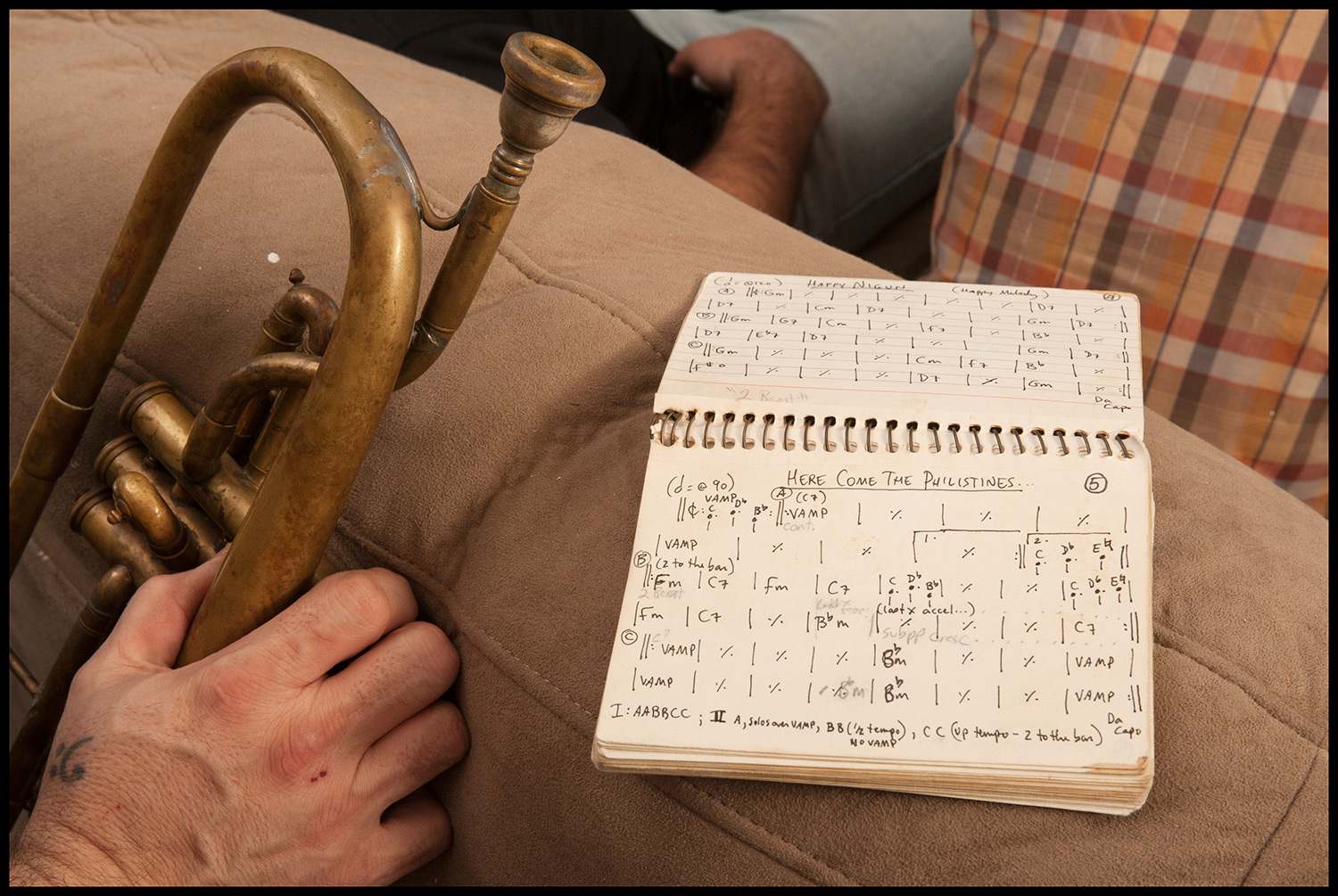

His Panorama Brass Band began small in 1995, a trio of clarinet, tuba and drums. A long stint at Lucky’s on St. Charles (a 24/7 bar/laundromat/music venue that is hard to imagine outside New Orleans) gave them a platform to find their way. They began to attract fans and musicians, eventually adding banjo, trombone, a string bass in place of tuba, then a tuba in place of string bass, an accordion.

Panorama is distinct in its embrace of “authentic” klezmer conjoined to the rhythmic imperatives of New Orleans. In the earliest years, Panorama was more purely klezmer, perhaps a response to the drift of the Klezmer All-Stars into louder and funkier terrain. Over time, Panorama’s scope expanded to embrace the beguine and other Caribbean styles, traditional New Orleans jazz a la Bechet and Jelly Roll Morton, and a wider range of non-klezmer styles from Eastern Europe like the Romany čoček.

A full-fledged marching band, the Panorama Brass Band, grew alongside the Panorama Jazz Band. The Panorama reputation spread, and they began to play in parades, at weddings, in clubs, some that even paid better than a tip jar. Over their first decade, they recorded two CDs and carved a nice New Orleans niche for themselves.

Then, Katrina.

The band scattered, with Schenck landing in Austin with his pregnant wife. Many of the Katrina diaspora never moved back. But the prospect of playing in the first post-Katrina Mardi Gras was too much to resist.

“After the storm we were all dispersed,” Schenck says. “I was in Austin and I was starting to think about when we get back, are we gonna have enough cats for the brass band?”

Just before the storm, a young woman from California had hit town, sitting in with everyone she could convince, Panorama among them. Schenck burned up the Internet tracking Aurora Nealand.

Ben: “I sent a message — ‘Aurora, we’re trying to get this brass band together for Mardi Gras, and I could really use you on alto.’ She came, and she’s been here ever since. And then we thought, let’s add her to the Jazz Band. That would be cool. We’d never had a saxophone, and her voice fit in perfectly between the clarinet and trombone. We had a complete thing with the six-piece: clarinet, accordion, tuba, banjo, trombone and drums. But adding the sax really became the thing.”

So it wasn’t really an accident, but it wasn’t really planned, either. Nobody knew the sax was the missing element until the sax was there. It’s one of the key moments in the 20-year history of Panorama. A very good band became astonishing. The addition of sax not only enriched the sound; Aurora’s sensibility also connected it more firmly to a wider jazz context. Even more critically, the band now had an improviser who could push the rest of the band into broader explorations. Not to say that she “made” or “completed” this band; it might just as well work the other way around. But there was an undeniable shift in the alchemy of the group once she joined. PJB was the same band after Aurora as it was before. It also became something more.

Here’s the hook: In Aurora’s hands, the saxophone becomes a force of nature, something incendiary. With a degree in composition from Oberlin and a stint at the Jacques Lecoq School of Physical Theatre in Paris, this self-described “skinny white girl from Half Moon Bay” cites influences as broadly spaced as Laurie Anderson, Morton Subotnik, Stravinsky and Charles Mingus. With Panorama as her launchpad, Aurora has established herself as a key figure in NOLA’s post-Katrina music, playing in duo with the incomparable pianist Tom McDermott, and leading her own bands, the NOLA-trad Royal Roses and the rockabilly outfit Rory Danger and the Danger Dangers. (She also maintains The Monocle, a vehicle for solo compositions and performance pieces that reflects the Anderson/Subotnik side of her personality.) Last summer, the Royal Roses appeared in New York’s Lincoln Center Midsummer Night Swing series and won the Best Traditional Jazz category in the Big Easy Music Awards. She’s been all around this world, and she grabs your attention whenever she plays. And she always comes back to New Orleans. And to Panorama.

Nealand displays an obvious Bechet affinity, especially when she plays soprano. Her serpentine improvisations recall Bechet immediately, and her tone has the vocal expressiveness that we hear in Bechet’s recordings. But it goes beyond that, her solos bearing witness to the extremities of her tastes while maintaining an organic connection to the material at hand. It’s the unexpected ingredient that made the gumbo taste better than ever.

When Your Narrator tried to get her to intellectualize about how she fits into the larger picture, she was having none of it. “Actually, I’m not really an expert on anything, so I don’t feel too comfortable speaking to how the jazz and klezmer traditions historically have intersected. I'm totally a non-purist on all fronts who just likes sounds.” This is really too modest by half; Nealand has solid training, historical curiosity and a pretty clear sense of her own voice and vocabulary. But her resistance to articulating her approach to a nosy journalist/fanboy is part of the instinct that makes the entire Panorama project so honest. Pick the material and treat it with respect. The rest will take care of itself.

Unlike the sax, the accordion has played a prominent role in Panorama almost from the beginning, and it’s another aspect of the PJB sound that stands apart. Despite close association with Louisiana music, especially zydeco and other rural/bayou musics, it rarely appeared under the traditional jazz flag. But it was a huge part of the Eastern European folk sound, making a perfect fit for Panorama, and another element that sets PJB apart from the usual New Orleans jazz sound. The latest occupant of the accordion chair is Matt Schreiber, and this cat is scary good.

Hailing from upstate New York, Matt was living in Maine. He knew a guy from Brooklyn who knew a guy who knew a music professor from Oregon who knew that Ben needed a new accordionist. He took an audition trip to New Orleans and was hooked.

“It didn't take long for me to become smitten with the band and the city,” Schreiber says. “I think Ben has such a strong vision of how the band should fit together in terms of personalities and instrumentation and that one of the things that makes the band unique is the importance of the accordion in the sound. There aren't a lot of American bands I can say that about.”

The current Panorama Jazz Band lineup — Schenk, Nealand, Schreiber, sousaphonist Matt Perrine, trombonist Charlie Halloran, banjoist Patrick Mackey and drummer Doug Garrison — is almost preposterously talented. Halloran is a regular in the Squirrel Nut Zippers and has shared stage and studio with Rickie Lee Jones, Calexico, Allen Toussaint and the O’Jays. Perrine — widely regarded as one of the world’s finest low-brass musicians in any genre — has worked with the Indigo Girls, Ray Anderson, Bonerama, Better Than Ezra, Bruce Hornsby, Nicholas Payton, Ellis and Branford Marsalis, Leigh "Li'l Queenie" Harris, and Aaron and Charles Neville, among many others. Garrison played with Alex Chilton before he moved to New Orleans to join the Iguanas. If you hop from club to club in New Orleans, you’ll likely see some of them playing in several bands in a single night.

Their immense skill never interferes with the central goal: Panorama plays social music, music that supports and enriches community, no matter where they play: a cramped bar, parading behind a Mardi Gras krewe, or providing the sacralizing music for weddings, funerals and bar mitzvahs. Their sense of fun is infectious and motivating; their ability to honor important social moments is moving and sincere, but never mawkish or corny. Like the best of their predecessors, PJB places themselves and their music in service to the people they are playing for and, somehow, they keep it on their own terms.

Pure chops aside, the Panorama Jazz Band stands out through their creative embrace of international styles that informed New Orleans music directly (Caribbean and African music), plus one that emerged completely independently, but on a uncannily parallel track: the broad range of Eastern European Jewish folk music generally lumped under the label klezmer.

Schenck insists that “the intention is to play the klezmer like klezmer, and then become a totally different vibe and play the beguine like a beguine. I’m not interested in fusion, like, What if we play a klezmer tune with a beguine tempo or groove?”

But you can’t escape yourself. Panorama infuses an unmistakable NOLA shimmy and shake into whichever style they deliver. Asked about this, Schenck agreed.

“It kind of happens, you know, because we live here and we drink this water and we breathe this air,” he says. “We live in this city and absorb this heat. You know when Doug plays a bulgar (one of the traditional klezmer forms), it’s got a snap on it. It’s Southern music. This is music from the Gulf South. If the same people were living and working up north, it would have a different vibe. So there’s always a sense of New Orleans music — that it kind of was here before the people were here, and it comes up out of the earth and comes through us. Because this place has a spirit, has an identity, has a being of its own. And our feet are on this place and have been for a long time.

“So I’m not trying to do that, maybe more letting it happen. We gotta play the way we play it. We’re gonna play it with a New Orleans vibe because we live and work here. So you don’t have to make it something else if you just let it become what it is. These styles influence each other.”

At an early 2016 date at the Cat, Panorama brought the full A-Team. (Whenever one of the regulars can’t make it, Schenck has a list of a couple dozen players ready to step in and deliver at pretty much the same level on their full book of 60+ tunes. It’s kind of amazing, really.) Gigs like this reinforce the special place Panorama inhabits in the New Orleans music scene. The soloists were never content to coast, especially the two Matts. All jokes aside about bass solos and the accordion in general, these guys deliver melodically inventive and rhythmically driving statements that reward close listening. The front line of Ben, Aurora and Charlie kept pushing each other to more outlandish experiments. It was a friendly competition, but no less fierce for the camaraderie. These guys came out to play.

Like the music that became jazz over 100 years earlier, Panorama’s synthesis of trad/klez/Caribe is not so much a clever idea of “let’s toss these things together and see what happens” so much as it is a result of respectfully juggling ingredients close to hand and resisting the mummification that can render tribute bands so fusty. Like all good NOLA music, PJB is fun, and danceable, and rowdy, and, sometimes, a little bit messy. But unlike a broad swath of players who pander to the expectations of the NOLA brand, Panorama avoids the easy conjuring tricks that can stall a music’s evolution. After 20 years, they keep pulling rabbits from the hat. In the January sets, PJB unveiled a couple of Venezuelan waltzes for the first time. It was a distinctly new element in their sound, but never felt out of place or grafted on.

Across the PJB four-CD catalog, plus one as the Panorama Brass Band (you can buy them all at the band’s website), as lineups changed and the band matured, the music remains true to Schenck’s original vision. The addition of musicians from so many places and traditions inevitably injects different flavors into the mix. It’s testimony to Schenck’s leadership that the original impulse remains intact with all the personalities and styles that continue to pass through the band. Panorama preserves the original nature of the ingredients even as they merge in natural balance. But it’s their gumbo, and you can recognize it as surely as you can recognize the difference between commercial roux and the deep brown potion Aunt Tressie took 11 hours to create.

Until the great Eastern European diaspora of the late 1800s, the largest Jewish community in the U.S. was in Charleston, South Carolina, comprised primarily of emigrants from German-speaking nations. From there, many set out to find their fortunes across the South, finding their way to small towns that had never seen Jews before. There they would establish local businesses — often as dry goods merchants — and integrate into the community as much as possible. This was the origin of many of the great retail dynasties like Rich’s in Atlanta, Pizitz in Birmingham and Maison Blanche in New Orleans.

Another outgrowth of this dispersal was temptation to assimilation. Always outnumbered, these pioneers were isolated. Even in places where the Jewish populations became large enough to sustain a synagogue, the gumbo effect led to some peculiar variations on tradition. As recently as the 1980s, one could attend the annual crawfish boil at the Reform Temple in Baton Rouge or a “High Holy Day Shrimp Fry” in Brookhaven, Mississippi. In New Orleans, The Brotherhood of Temple Sinai hosted an annual shrimp boil fundraiser for years. More observant families shared recipes for kosher gumbo. Whaddaya gonna do?

The Jewish community in New Orleans dates back to the first recorded Jewish resident, Isaac Monsanto, arriving around 1750. Variously described as a merchant, shipping magnate, banker and import-export businessman, it seems Monsanto made a fortune in the slave trade. But around 1769, the Spanish began to view Jews in New Orleans as an economic and conspiratorial threat, and Monsanto was forced to flee, his fortune in ruins. Given his profession, it’s hard to argue he didn’t deserve his fate.

(While we can justly curse Monsanto, it’s worth noting that by the 1830s, for example, there were more than 700 freed black New Orleanians who owned slaves themselves. One of these owners-of-people stated simply, “It’s for convenience.” Any attempt to paint one ethnicity or another with a broad morality brush is doomed to paint an incomplete picture.)

A more admirable character is found in the story of Judah Touro, who moved to New Orleans around 1800, made a fortune, fought in the Battle of New Orleans — where he was nearly killed — and recovered to make another fortune. Legend holds that he strictly avoided cotton trading due to its tight connection to the slave trade — and that he bought several slaves just to set them free. The truth on this is slippery, but there is no question that Touro — who enjoyed a very modest lifestyle despite his great wealth — was an active philanthropist whose generosity extended to his entire community.

Your Narrator actively wishes to believe the best about him. Naïve or rational? You be the judge. In 1823, Touro bought the First Congregationalist Church when it was suffering financial troubles. He promptly deeded the building back to the congregation, along with a sizable donation to help stabilize their finances. In 1849, the church burned to the ground. Touro paid to have it rebuilt. Apparently, he also was one of the primary donors to preserve and memorialize Bunker Hill in Massachusetts. Examples like this abound in the mythology. Your Narrator is comfortable in his naiveté.

The Touro name retains a prominent place in New Orleans, despite the fact that he never married or had children. He was a generous donor to the two synagogues in New Orleans during his lifetime, one Ashkenazic, the other Sephardic; these have since joined to create the Reform Touro Synagogue. Shortly before he died, a yellow fever outbreak swept New Orleans, so he funded the Touro Infirmary, which still operates — in much expanded form — on its original site in the Garden District. He lived modestly and gave lavishly.

The Jewish community in New Orleans was not especially large, but its contributions to civic life and economic vitality were considerable. Retail outlets like Rubenstein’s, Godchaux’s, Adler’s and that great beacon of K&B purple — open all night, your source for aspirin and pepto and bandages and maybe a late six-pack. Cultural institutions like Delgado Community College, the Museum of Art in City Park and the Isidore Newman School. New Orleans civic life is marked by the rich contributions of its Jewish citizens, but despite this, beyond the few synagogues, New Orleans culture bore little overt evidence of Jewish influence for most of its nearly 300 years.

Still, the place of Jews in New Orleans was subject to the same whims as any other minority. It’s worth remembering that the Klan hated not only blacks, but Jews, Catholics and all other “mongrel” breeds. Miscegenation — physical and cultural — was the greatest threat to their worldview, and woe betide anyone who got in their way. The efficient anti-Semitism of the 20th century made no distinction between assimilated and “ethnic” Jews. Neither did the racists of the American South give a tinker’s damn about grocery-bag hue, their binary view of black/white leaving no room for subtle racial distinctions.

Black was Black. Jew was Jew.

The parallel hardships that these cultures have endured — centuries of oppression, violence, and forced segregation alongside fitful interludes of acceptance and assimilation — are with ample bitter irony the wellspring of their distinct and rich folklore. The internal divisions and score-keepings that are so tragically human and sad add another dash of vinegar to the pot.

But this is New Orleans, damn it, and it’s the place that care forgot, where it’s always a party, where the inescapable inequity and violent past are papered over by the next parade, the next cocktail or feast. So let’s get down to the world’s prevailing image of NOLA and leave our troubles behind.

Mardi Gras’ roots are in medieval Europe, with more recognizable elements — like the boeuf gras, or fatted calf, a clear antecedent for the excessive consumption leading up to Lenten denial — handed down from the French House of Bourbon. America’s first Mardi Gras — in 1703, in what is now Mobile — occurred under the auspices of the Masque de la Mobile, a “secret” society that is precursor to the Krewes in New Orleans. Migrating west, Mardi Gras celebrations sprang up in Biloxi and, finally, in New Orleans in the mid-1700s, but with none of the organized bacchanal that we know today — some scattered parade-like events, maybe a society ball here or there, but none of that stumbling, bead-grubbing frenzy of inebriates flashing tit for swag that we’ve come to know and love.

The “official” NOLA Mardi Gras we know began in 1857, spurred by businessmen who wanted to emulate the commercial benefits of Mobile’s celebration. That was the birth of the Mistick Krewe of Comus, which remains the oldest — and most exclusive — krewe. Next among the venerable krewes comes the Rex Organization, emerging in 1872 to revive and bring some order to Carnival following the unpleasantness between the States. Today, Rex remains among the elite, and the visit on Mardi Gras night by their King and Queen to the Court of Comus is a ritual peak of high society Carnival.

And the first incarnation of the Rex, King of Carnival, was a Jewish businessman named Lewis J. Salomon.

Lewis J. Salomon

Salomon had taken on the job of fundraising for Rex a few weeks before their first parade, in 1872, and the crown was his reward. Today, Rex is one of the most lavishly funded and ostentatious carnival krewes around. Member dues and out-of-pocket expenses for things like costumes and throws run to many thousands of dollars per person. But in 1872, dues were modest. There was no float. The Krewe walked, and the King walked alone: He had no Queen. It was a humble beginning for one of New Orleans’ most prestigious social badges.

It was also the high-water mark for Jewish participation in Mardi Gras for at least the next 100 years. While recent years have witnessed the emergence of Jewish-themed krewes, for years many Jewish citizens found Mardi Gras a convenient time to take vacation, the better to get away from the embarrassment and heartbreak of exclusion from their hometown’s signature celebration.

A classic 1968 Calvin Trillin article in The New Yorker took a deep look at the polite-ish anti-Semitism of Mardi Gras 50 years ago, taking note of the annual exodus during Carnival and noting wryly that “[i]t might fit the Latin image of Mardi Gras if the exclusion were based on the religious implications of a pre-Lenten celebration, but, as a matter of fact, Mardi Gras in New Orleans was started by Anglo-Saxon Protestants and has never really had any religious significance.” It’s worth noting that nearly 50 years on, the Trillin article is still remembered and vigorously debated within the New Orleans Jewish community. Some call it “such dreck.” As with so much so-called history, very little is settled.

Still, we can stipulate that Mardi Gras is, by origin, a religious-based celebration with deep roots in Franco-Catholic tradition, and that for many people in majority-Catholic New Orleans, it remains just that. As the calendar closes in on Lenten abnegation, Mardi Gras is similar in function to other celebrations such as breaking of fasts at Yom Kippur or Ramadan — albeit with the relief afforded before the penance — so a certain amount of religious ownership might be understandable. But enthusiastic and excessive displays of hedonism have, over the years, converted Mardi Gras into an inherently commercial and recreational holiday, like Christmas, and thus secular as all get out in the eyes of revelers and merchants. After all, any event that can be (more or less accurately) stereotyped by excessive alcohol consumption, a breast-based exchange rate for beads and trinkets, and a general suspension of various behavioral norms makes it near hopeless to justify exclusionary diktats on any grounds, much less religious ones. Besides, that kind of stuffiness can really annoy the entrepreneurial sorts who are more than happy to charge $20 to park your car in their yard or sell you a 32-ounce walkaway Hurricane — the equivalent of a quickie-mart slushy with a whiff of lower-shelf liquor — for $15.

Trillin nailed it way back when: “The crowd watching the parades in the French Quarter or wandering up and down Bourbon Street during the general costuming on Shrove Tuesday has consisted increasingly of that band of all-purpose American event-attenders who seem to have emerged from some gigantic incubator in Fort Lauderdale, carrying beer cans.”

Some things never change, or maybe they just become more themselves. Today’s Mardi Gras is about the serious business of attracting as many people as space allows, plus some, with a keen eye on maximum simoleon extraction. Exclusion is bad for the bottom line.

Walker Percy’s take on Carnival was, naturally, more caustic than Trillin’s. “Thus, a trivial byproduct of New Orleans Catholicism, Mardi Gras, has been seized on by tourists, appropriated by local Protestants, promoted by the Chamber of Commerce, as the major cultural attraction. Nice ambiguity, I say, because each party is content to have it so. Nobody is offended.” Nobody, reckon, except the people who were excluded from Mardi Gras proper.

Alongside the growth of white Mardi Gras traditions, the city’s African-American community was creating its own take on the Carnival season. Organized around the Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs, these community-based groups threw their own parades and balls. The tradition of the Mardi Gras Indians, with their elaborate costumes and ritualized battles, developed under the radar of white New Orleans. A rich subculture emerged, one that eventually identified New Orleans to a degree that the dominant culture could never hope to achieve.

Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs and Benevolent Aid Societies were far more integral to their communities than the white Krewes. The parades — which were not limited to the Carnival calendar — were important, but the essential function of the Social Aid societies was as social safety nets to the city’s poorer residents. Club members could rely on their fellows in times of crisis and need. When a member died, the Club would frequently handle funeral arrangements and expenses, including organizing a Second Line parade in honor of the deceased. Music’s function as glue and lubricant for this community served as both force and forge in the creation of jazz.

Boiling it all down: The tradition of Mardi Gras, as developed by Anglo-Saxon Protestants, created space for one of the world’s greatest ongoing folk-culture celebrations. Not for nothing, the responses to the earliest Mardi Gras race/class/gender restrictions provide another gorgeous example of how out-groups can transform a closed ritual into something more layered and beautiful than its initiators ever could have imagined. Let’s try to imagine Mardi Gras with nothing but straight, white men of society’s upper crust.

Sorry. Did that image make you doze off for a minute?

The fact that it took marginalized communities to create the gumbo is just another example of the greatest — and most recurrently sad — story ever told. These examples of true-genius response to enforced exclusion/subjugation highlight the bitter irony that restrictive codes — both in spite of and because of their awful cruelty — seem essential to the gumbo. And we’ve barely touched on the transformative contributions of the Mardi Gras Indians, the Baby Dolls, Cajun influences or the LBGTQ communities, to name just a few. Any complete history of Mardi Gras would fill a library or three.

While none of this can excuse or romanticize horrific human suffering, it is no coincidence that great folk-culture innovations often occur under creative friction imposed by institutional oppression. Which fact raises the hard question of whether those from outside a community have any right to enjoy and fetishize these cultural expressions, much less expend several thousand words purporting to explore/explain what it all means. Which certainly points multiple accusatory fingers back at Your Narrator. The fraughtness becomes almost unbearable.

If the grand expression of Mardi Gras is evident in the topline mega-krewes, more egalitarian impulses live in the “lesser” parades and krewes. One of the most popular is the Krewe du Vieux, formed in 1987 as a splinter from the Krewe of Clones. The Clones, it seemed, had become a tad too respectable.

KdV parade themes rank among the best, and most profane, public spectacles of political and social satire in a nation sorely deficient in that sphere. A wander through their Marigny warehouse is to marvel at the creativity, vitriol and pungent humor KdV encourages. From the rafters dangle creatures from parades past, like the enormous papier-mache model of George Bush surrounded by anatomically-correct-yet-enormous breasts and penises that recall the passions our last President aroused in post-Katrina New Orleans. Next to him hangs a well-hung Pee Wee Herman; go figure. Their satire is target sharp and dizzyingly sophomoric, the barrage of punning as relentless as the preoccupation with bodily fluids. Anyone bothered by scatology or genitalia — or who holds political conservatism dear — will no doubt be offended. The denizens of Krewe du Vieux care not a damn.

KdV is loads of fun, unabashedly liberal, and, since it occurs before the tourist invasion, a favorite of locals. The floats are mule drawn, allowing the parade to traverse narrow French Quarter streets, a charming throwback to Mardi Gras past. The weather is usually cold as brass balls, encouraging a strange mixture of costume/protective wrapping and futile attempts at warming via alcohol.

Enter L.J. Goldstein to our story, a Philadelphia native who moved to New Orleans in 1994 to become a photographer. Goldstein was fascinated by the way Benevolent Aid Societies — especially the Zulu club — re-appropriated racial stereotypes and used them to mock white culture. Beginning in 1909, the “tramps” of Zulu wore rags and grass skirts and marched in blackface, while their King carried a banana stalk scepter emblematic of their purported jungle nature. Because they were black, they were relegated to the back streets on parade day. True to their Benevolent Aid Society roots, the Zulu organization is highly visible throughout the year, fundraising and donating to educational and other community initiatives.

Zulu’s radical approach to inverting the clichés of Southern racial attitudes did not sit well with everyone in the black community, many finding it undignified and degrading. During the ’60s tumult, membership in Zulu was especially frowned upon. It was only in 1968, the year of Trillin’s visit, that Zulu was allowed to parade on any of the city’s main streets. Gradually, (most of) their community has come to see Zulu as integral to black identity in New Orleans, and for the masses, the Zulu coconut has become the prized trinket of Mardi Gras season.

Zulu was the krewe that L.J. fell in love with, and he set out to document as much of their activity as possible. On Mardi Gras Day ’95, L.J. was taking pictures of the tail end of the Zulu parade. Along came an uninvited marching band — the New Orleans Klezmer All-Stars with Ben Schenck on clarinet — tagging along behind the parade. With the Zulus as a template, L.J. began to imagine a krewe that would afford Jews a vehicle to reclaim their own cultural stake in the city. At a Seder in 1996, Krewe du Jieux was born as a sub-krewe of Krewe du Vieux, and their broad humor and glitter-painted bagels made them a perennial crowd favorite. A century and a quarter after Lewis Salomon served as Rex, Jieuxs had a krewe of their own.

Goldstein’s grand scheme was to invert traditional Jewish concepts “and blend them into a modern secular Judaism that honors the African-American participation that makes New Orleans special. New Orleans is on the map because of African-American culture. But look into that history and you find Jewish participation. Look, even Louis Armstrong wore a Jewish star around his neck.” For Goldstein, appreciation for Jewish contributions to New Orleans was overdue.

The satirical strategy has obvious roots and parallels with early plantation-bound slaves performing in blackface and using comic effect to poke fun at their white overseers. The pretense of agreeing with stereotypes camouflaged the aim of ridiculing the overlords for their ignorant bigotry and lack of self-awareness. The subterfuge was so effective that eventually white performers appropriated the gestures and dialect — and yes, the blackface makeup — for themselves, at which time minstrelsy lost its effectiveness as cultural weapon, becoming just another episode in a long tradition of whites stealing African-American culture and claiming it as their own.

This theft and deception rendered what had been an effectively slashing form of satire into a grotesquely offensive parody. It wouldn’t be the last time and it points to the chief hazard of trying to turn stereotypes back against the bigots — they may very well miss the point and see the mockery as confirmation, turning the tropes back again. Self-awareness ain’t just a river in Egypt, and lunkheads are gonna lunk. It can get truly dizzying, especially as musicians like the Carolina Chocolate Drops and others reclaim the cultural roots of minstrelsy as a point of pride.

This potential for backfire may explain the resistance within the tricksters’ own communities to the strategy. As with the Zulus, the Jewish community did not greet Goldstein’s campaign to neutralize anti-Semitism through ridicule with unanimous praise. Many found it undignified, the broad comic embrace of ethnic stereotypes more painful than funny. Others just thought it was unseemly, too showy. Why attract so much attention? But as Krewe du Jieux approaches its 20th anniversary, it continues to provide New Orleans’ Jewish community a creative platform for embracing Carnival that was unthinkable when Trillin shared his findings. And because they continue to push the limits of taste and hazard, the double-edged blade of satire looms precariously over everything they do. Tricksters have always made people uncomfortable.

To wit: On Jan. 9, 2016, KdJ gathered at the Spotted Cat for Panorama’s weekly gig to crown their royal court. L.J. arrived in a full-length fur coat and pimp hat with devil horns; he was also sporting Groucho-style fake nose/glasses. Laura, the Krewe Captain, took the stage to crown the court. First up, the wRich Doctor (Zulu crowns a Witch Doctor), dressed in surgical garb decorated head to toe with dollar bills pinned to his scrubs. Next comes the Big Macher (Zulu crowns a Big Shot), in full Rothschild-esque tails and top hat. Up next, the Court’s Princess, naturally a Jewish American Princess (emphasis on the J.A.P. epithet as an honorific), decked out in gold lame, with gold credit card earrings that have passed from princess to princess over many years.

Finally we arrive at the culmination, the crowning of the Shabbas Queen. Simone is resplendent in blue wig and makeup, and she receives her tiara with all the elegance of a once and future Queen Mother, if QM were ever to find herself in the elegantly grubby confines of The Spotted Cat.

At this point, Your Goyish Narrator has to confess to a certain level of ambivalence about the spectacle. Having heard about the ritual ahead of time, he thought himself well-prepared to analyze the contradictions and appreciate the sub- and re-contextualizing that was going on. By the time the Queen of Shabbas was crowned, Your Narrator was getting comfy with the premise of self-mockery as effective strategy.

Then the Queen’s husband took the stage to be crowned as Royal Consort. This was purportedly a minor role, but L.J. had another trick up the sleeve of that fur coat. The Royal Consort was re-christened as King of the Jieuxs and crowned with a three-dollar Native American toy headdress with a hand-drawn Star of David on the front.

Brain spasm. NO!, thought Your Narrator. This is not OK! This is not your cultural signifier, and you have … no … right.

But the new King was beaming, and he pulled out his flute and played a most gorgeous Native American melody. And then Your Not Very Bright Goyish Narrator understood: The King is himself full-blooded Native American, and the dime-store headdress — which was a complete surprise to the new King — was L.J.’s brilliant strategy of incorporating the King’s cultural heritage into the broader KdJ strategy of owning and flipping. This giant, barrel-chested man was smiling from ear-to-ear, eyes glistening, suffused with the honor bestowed him by this other tribe that he had married into.

And at this point, Your Narrator realized that he was dancing with a smiling Orthodox Rabbi from the Garden District and embarrassed as always at having to display his total absence of dance chops in public, but whatever, let it rip, and we toasted each other with a shot of Maker’s Mark and laughed at the absurdity and beauty and joy of the whole affair.

And L.J. was making the rounds, handing out snack-size portions of his signature "Jieuxffuletta" sandwich (lox and a schmear on bagel, natch), and there was laughter and hugging and dancing and the fraughtness began to seem not so heavy any more.

And then it was time for the ramble, a second line parade through the Marigny and parts of the Quarter. Just another New Orleans tradition grafted onto the KdJ celebration, right?

Right?

A modified version of Panorama Brass provided the soundtrack, and our Royalty led us into the streets for…

Wait for it.

You’re really not ready.

OK, here goes.

Yeah, the whole flipping and owning thing starts to get very, very fraught again, and Your Goyish Narrator is suffering more than a little pang of guilt at being part of something this … this … fraught, damn it.

And now L.J. the Trickster is on Frenchmen Street with a bullhorn, exhorting the band and the royals and the rest of us with chants of “RUN JIEUXS! RUN!” Again, fraught. And also a little thrilling, as transgression always is. Your Goyish Narrator laughs a little every time it happens, and then cringes just a bit. What would the in-laws think?

The first couple blocks were crowded with wanderers. Lots of flashes going off, and a few quite evidently non-Jewish passersby in camo fatigues just a little too excited to chant RUN JIEUXS! RUN! themselves, and more than a few people stepping into traffic to give the Krewe a wide, wide berth.

Like any good second line, the gaggle managed to inconvenience more than a few motorists, most of them eventually tooting their horns in time with the band. Crossing into the Quarter, the street crowds thinned out, leaving only occasional bands of tourists in our path.

“GIMME AN ‘O’!

“GIMME A ‘Y’!

“WHAT’S THAT SPELL?”

All the while Panorama is serving up some delicious klezmer, and our pass at Molly’s at the Market — and later at Harry’s Corner — provided badly needed spiritual reinforcement, and the RUN JIEUXS! RUN! chant kept cycling back around. A ramble down a few residential streets lured people to their front doors where they were given official Jieux Eggs, blue plastic eggs filled with a King Baby (circumcised, certainly) and a little note of greeting: “Everybody loves a Jieux Egg.”

Halfway to Harry’s, we realized that about half the krewe was still at Molly’s, waiting for their (first or third) drink. L.J. turned the marchers around and had Panorama strike up the classic Mardi Gras Indian anthem “Let’s Go Get ’Em” and more people opened their front doors to find out what the hell, and soon we were back at Molly’s to collect the wandering flock, and to lose a few more when we marched again.

In front of Harry’s, Your Narrator found himself in deep philosophical musings with the Krewe’s posek, Rabbi David of the Orthodox Anshe Sfard Synagogue. Krewe Captain Laura tells us that, “We seek his guidance when we have questionable ideas and he tries to keep us ‘basically kosher’ in all that we do.” So the posek, in cooperation with an official Krewe mashgiach, keeps the krewe from crossing a vaguely drawn line. A suggestion to knit yarmulkes to look like bare breasts apparently crosses this threshold. Good to know.

Later, YGN and the Rebbe were back in front of Molly’s again — and yes, we were reunited with the several who had been “lost” before — debating and toasting each other with another shot of Maker’s (or maybe only YGN took a shot, the Rabbi certainly having better impulse control than YGN). A marcher who had been following our ersatz Talmudic pondering (ersatz on YGN’s part, anyway) needed to break in and tell us how he felt about all this.

Stu was in town with family from New Jersey. He and his wife and sister are Jewish. Asked if they had come to town just for this, Stu told us how he heard about it by accident at the hotel, and that they were so shocked and offended by the description that they just had to come and see what the hell was going on.

Proceed.

Turns out Stu was experiencing the greatest flood of Jewish pride he’d enjoyed in years. All the while YGN was fretting about the fraughtness of the whole enterprise, Stu and his family were having the time of their lives.

Stu: “This is one of the greatest nights of my life. I’ll remember this until the day I die.”

And it was this moment when YGN turned to Admiral L.J. Goldstein (Ret.) and said, “This is the most offensive, horrific, beautiful, and joyous thing I think I’ve ever seen.”

And the Trickster laughed and said, “Yeah it really is, isn’t it.” You’ve never seen a happier man. Two of us, really.

So this whole paradigm is funny as hell, and at the same time, as gut-wrenchingly challenging and, yeah, fraught, as any social event can be. Perhaps inevitably, some members grew tired of Goldstein’s evangelistic mission. Just lighten up and have fun, and maybe embrace the more pornographic elements of Krewe du Vieux while you’re at it.

L.J.: “It’s too much work to just end up parading around with your schlong hanging out. The physical space/time and emotional gravity that it takes to make art is too precious to throw away. I live in New Orleans. If all I want is fun, I have 30 options every day. This is bigger than that.”

And thus it came to pass, following the Great Flood of Katrina, that the great Jieuxish schism of 2006 occurred and, after lengthy negotiations, a splinter tribe formed Krewe du Mishigas. L.J. and team kept the Jieux name and Mishigas kept the Krewe du Vieux slot. In 2006, both factions marched in Krewe du Vieux, with the founding members of KdJ all joining L.J. to march as a sub-sub-krewe in Krewe du Chaos. Cast out from their home parade, L.J. and gang dubbed themselves The Wandering Jieuxs.

From 2007 to 2009, Krewe du Jieux wandered with no official parade to call home. But they had their name, their heritage, their identity, so The Running of the Jieuxs was born, a sort of guerilla parade that preceded the Krewe du Vieux parade by an hour or so. Poet and NPR commentator Andrei Codrescu was the first King of the Running. A new tradition was born, and word has it that Sasha Baron Cohen of "Borat" fame approves of the appropriation of his flipping and owning. The layers, they are many.

In 2010, Krewe du Jieux helped launch the newly minted “krewedelusion” parade, which marches along roughly the same route on the same night in January, buffered by slightly staggered start times to ward off any potential confrontation. It appears these rivalries are reasonably good-natured; nobody has nailed a thesis to anyone else’s door. Yet.

At this point, the patient reader has got to be wondering wtf this is all getting at. So, at this point, YGN breaks the fourth wall to explain that it was through accident of fate that he found himself marching with Krewe du Mishigas in January, 2007, the first year that Krewe du Jieux was in fact excluded from their traditional parade home. The honor — experiencing a Mardi Gras parade from the inside after a lifetime jostling with huddled masses hoping for a stray doubloon — was singular. We were mobbed by event-attenders eager to flash nip to gain a glitter-painted bagel, the Mardi Gras throw for those in the know, second only to the Zulu’s coveted coconuts. A modest man, YGN did not demand bare bosom in exchange for his small supply of sparkling bagels, but offers of tiny bottles of Jack seemed a fair trade.

But the best of it? Every Krewe has its own brass band to pump up the marchers and the crowd. Our band that year? The Panorama Brass Band. That’s where YGN found himself smitten with the Panorama gumbo, a love affair that has lasted ever since. And now, through the twists and turns of kind fate, YGN finds himself a member yet again of a Hebe-krewe marching in front of Panorama. Your Goyish Narrator is now a member of Krewe du Jieux.

Schism, shmism.

The Panorama Brass Band rarely plays a club date, but Mardi Gras gives them ample opportunity to raise a ruckus. PBB marches throughout the season, sparking the krewes of Morpheus, St Anthony’s Ramblers, Tucks, Tit Rex, and King Arthur, among many. But their season begins at the roots: rolling with Krewe du Jieux at krewedelusion.

The Panorama Brass Band album 17 Days was recorded during the 2010 Mardi Gras season, just after the Saints won their Super Bowl and the long shadow of Ray Nagin was cast away by the election of Mitch Landrieu. New Orleans was feeling good, ready for the celebration of Carnival, and Panorama Brass was ready, too. For seventeen days, PBB played at least one gig or parade a day. And incredibly, recorded a baker’s dozen tracks in between.

The recording only hints at the power the PBB delivers live. First off: the Brass Band is loud. Real loud. Blow your hat off goes to eleven loud. But beyond that, PBB catches crowd energy and reflects it, enhanced, creating a feedback loop that demands to be called hair-raising. The parades cover several miles. That’s several miles walking, carrying and playing your instrument, often enjoying the sensation of hands and feet and lips going numb from the cold. And they Never. Ever. Stop. The energy never flags. The role of the band in the parade is too important to let fatigue, lip pain, or frozen extremities get in the way of the music.

Ben’s liner notes paint the picture:

From that moment until about 3 p.m. on Mardi Gras day, two and a half weeks later, our small tribe of orange and blue clad musicians will be hustling around town making it to a lineup or bandstand just in time for the downbeat. And there it is: that sound.

That sound, when everybody is in position, we count it off and hit it, is what gets us down the street from start to finish. That’s what makes us keep blowing even after the point, halfway through the first couple of parades, when our chops give out.

The parade — and the music — must go on.

This year’s Ruler of krewedelusion is Blaine Kern, legendary float builder for over half-a-century. His creations are enormous, elaborate, and expensive works of master craftsmanship. (Apologies for the double-gendered terminology. Mea culpa.) But none of Blaine’s mega-floats are on hand tonight. To find him at the head of this procession of small and humble krewes is yet another indicator of the way Mardi Gras can both reinforce and blur the economic and social distinctions of New Orleans.

At his coronation, Kern captured the vibe perfectly: "You guys represent a different aspect of Mardi Gras than I knew about, but it's also a very, very important one. The thing is, Mardi Gras, in all its different phases, belongs to all of us."

At the high end, Endymion with its $7.1 million annual budget is the most lavish affair, with their post-parade party at the Superdome headlined this year by Pitbull and Steven Tyler. Their 2015 float — which holds around 250 riders — clocked in at around one-and-a-half mil, and they shelled over 800k for food and drink.

krewedelusion lives at the other end of the parade economy. The total outlay for this year’s KdJ spectacle is, according to Goldstein, “between 1/500 and 1/1000” of Endymion’s float alone. Parade and sub-krewe dues are minimal-to-non-existent. Krewe members build their own floats and often create their own trinkets and throws. It’s all very DIY. It’s a lot of work, building a float, creating a few hundred glitter-painted bagels, coming up with costumes, organizing the people and logistics. All for a little parade? Why?

krewedelusion takes KdV’s retro approach a step further; instead of mule-drawn floats, the delusion inner-krewes push and pull their floats themselves. You can bet they take that into account as they design their displays, knowing well that pushing/pulling a float for five miles while you’re both freezing and drinking and lofting painted bagels to the throngs is no walk in the park.

The rented warehouse under the Robertson overpass in the Bywater is nearly empty when YN arrives on parade day. The Jieuxs were still putting the finishing touches on their float even as the rest of the krewes rolled out to the parade route. Scissors, glue guns, staplers, bunting, glitter, drills, nothing where you left it and a good dozen people getting in each other’s way, including the interloping Narrator who finally found a way to contribute, and really, here is the moment where the hazard of being an imbed correspondent becomes most acute. YN, resplendent in orange-face, casually and carelessly slipped across the blurry line between observation and participation.

So it got personal, all pretense of detachment pretty well done for. And that’s where the Why? found an answer: participatory-anarcho-democratic spectacle mongering is a reward in its own right.

These are not event-attenders; these are event creators. In the end, working to create a krewe and marching it through a pressing crowd of revelers is an act of sacrament, an offering to a city and its people, those still alive and long since dead. Despite the gap between the original Catholic roots and the prevailing cult of hedonism, Mardi Gras is an act of tithing, and this joyous sacrifice is surely one of the most important elements of New Orleans’ soul, a unique pan-culturalist propitiation that allows this nearly 300 year old city to sustain an honest (mostly) connection to its rich cultural heritage — warts and all.

Precisely at sunset, the Rabbi delivers his havdalah, his blessing. And at last, Panorama snaps the downbeat and we’re off, marching from the Bywater, through the Marigny and down Frenchmen past The Spotted Cat, then around the Quarter by way of Decatur, Toulouse, Royal, and St. Philip Streets, and back the way we came. The crowds are huge, the exchange of goodwill between marcher and watcher almost overwhelming. Everybody wants a high five, a glittery bagel, something. People are laughing and pointing and smiling. This is the City That Care Forgot.

Reading a Mardi Gras parade is like reading a stained glass window in a cathedral. The stories are rendered in full display; if you grew up in the tradition, you know just what that saint carrying his own severed head really means. Otherwise, it’s just a cool picture, yours for the decoding. You don’t have to know the story of St. Denis to get a thrill, but it sure wouldn’t hurt.

The krewes offer the same kind of tales for anyone who wants to dig into the core. For anybody else, it’s a great time to stand on the sidewalk and yell “Happy Mardi Gras!” to passing strangers, to beg for trinkets and gawk and laugh and have a generally awesome time with several thousand of their closest friends. Either way, the krewes present their offering, freely, for the throngs to do what they will. You don’t have to know the backstory, but you can bet that every krewe has at least one good fable behind it.

Panorama is, as always, on fire, their expanded 11-piece lineup bringing the shtetl to the Quarter. Even cooler: in front of us, Tap Dat (a krewe of several dozen tap dancers) has brought along the All for One Brass Band; behind us, Krewe du Chieux (foodie themed) has the Slow Rollas Brass Band for encouragement. Cumulative volume level? Really fucking loud. One can only imagine what the passing parade sounded like to stationary viewers, but on the inside, it was something like a Charles Ives symphony, or maybe one of Anthony Braxton’s massive multi-ensemble works. The rhythms would synchronize and diverge, the tonal centers would and would not relate. It was like living inside a radio that was transmitting several stations at once. And it was magnificent.

One especially fine moment: Panorama playing a piece with lots of stop-time breaks, with two different beats and melodies coming from ahead and behind, neither of them anywhere near the PBB tune — or each other, for that matter — and the epic concentration and intensity of the Panorama gang to hit the breaks with precision. And the music of three bands merges into one glorious, cacophonous whole, a polyrhythmic/tonal/phonic orgy of sound, a chorus of angels blowing trumpets and trombones and banging the drum in offering to appease the gris-gris and inexplicable mojo of all sorts, and you are marching through the cradle of the American South, the epicenter of American cultural innovation, with the world’s only klezmer/second line brass band blowing every mind within hearing, and you are buzzing and smiling and dancing your ass off in New Orleans.

Isn’t this where we came in?

If nothing else, this culture ramble justifies our despair over teasing out the origin of any kind of, well, anything really. Now we arrive at the end, which is just as tricky. This isn’t an episode of “Law & Order,” bub, so try not to get too upset if all the loose ribbons and beads fail to tie up neatly. Resolution ain’t all it’s cracked up to be.