In the fall of 1997, I flew down to Tampa early one morning to meet Truman Capote’s aunt, Marie Rudisill. As a reporter for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, I had already been to Florida once that year — to cover the mysterious killing of fashion designer Gianni Versace. After several intense days and nights, chasing clues in Miami gay bars and waiting for the bizarre murder-suicide to play out, my interview with Capote’s 86-year-old relative would be a piece of cake, right?

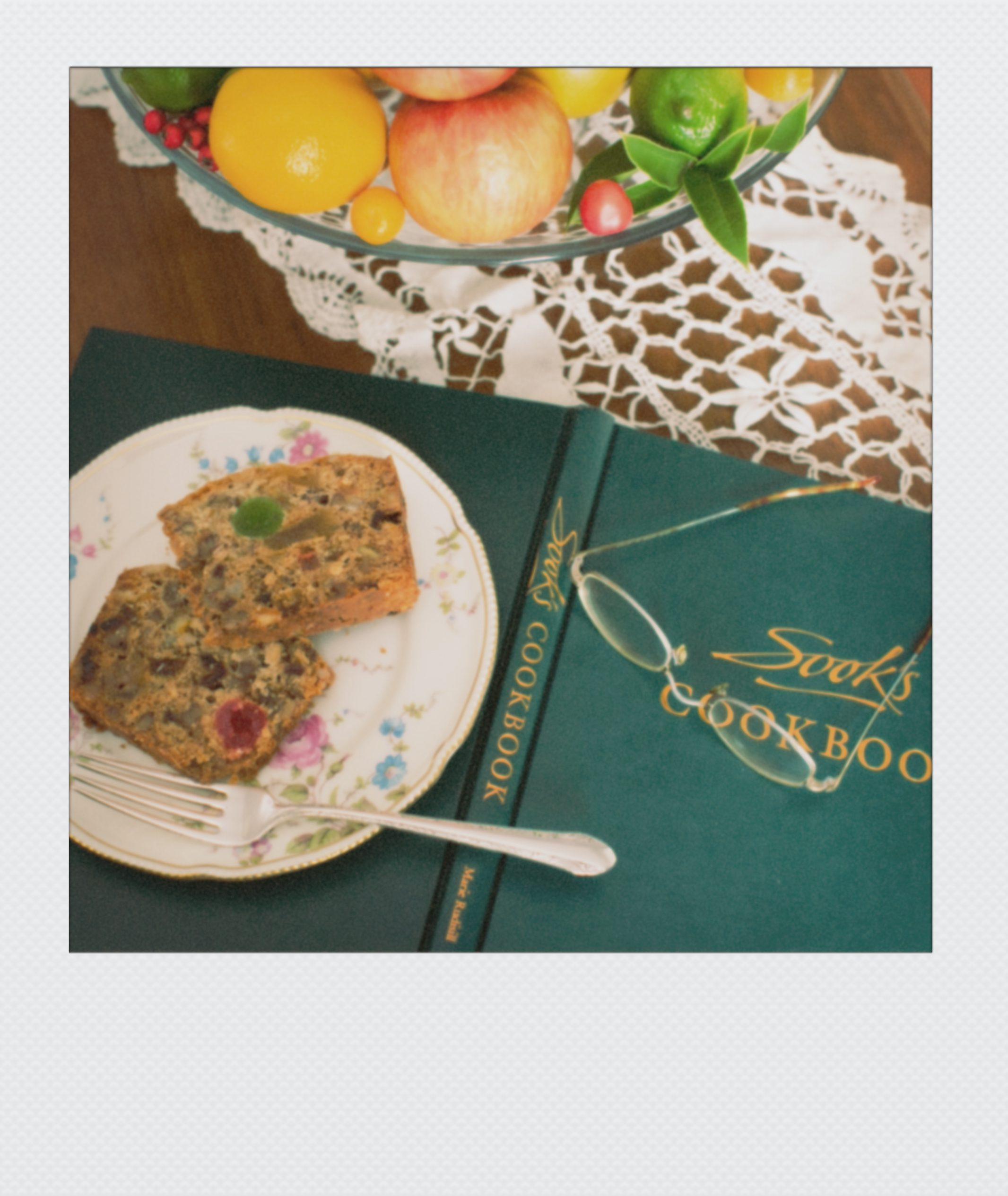

All demure and gracious, she’d probably put out biscuits, butter, fig preserves. We’d sip coffee out of heirloom china, and she’d prattle on about what an adorable and precocious little boy Truman was. She’d explain how he based his classic fruitcake odyssey, “A Christmas Memory,” on their distant spinster-cousin Nanny Rumbley Faulk — or “Sook,” as they called her — with whom they’d both lived in Monroeville, Ala. Over a second cup, we’d reflect on Rudisill’s own collection of recipes, “Sook’s Cookbook: Memories and Traditional Receipts From the Deep South.” I’d return to Atlanta, file a sweet little feature, whip up a batch of Rudisill’s Real Plantation Eggnog and congratulate myself on writing an authentic Yuletide heart-warmer.

This is not how it turned out.

Instead, I find Marie Rudisill — whom Truman Capote called “Aunt Tiny” — living in a charmless mobile home in Hudson, Fla., outside Tampa. A diminutive, birdlike woman, she wears her long white hair coiled in a bun. She’s recovering from a broken hip and has been diagnosed as diabetic.

Her husband, James, has died of cancer in 1990. Her son, Jim, and his wife have parked their RV on her lot so they can look after her. She is trying to live on her monthly Social Security check of $1,200 and is desperate to make ends meet.

“I have sold everything I have got,” she tells me in a panic.

“My husband gave me a gorgeous Cadillac car the year he died. I sold that. I sold my big home [in Florida]. I sold my home in South Carolina. I sold every antique I got.”

The tea cakes and finger sandwiches never appear. Instead, her son and I go for some takeout barbecue. When we put Rudisill’s pork sandwich in front of her, she says: “Am I supposed to eat that?”

When Rudisill tells me about her innumerable cats and the two opossums she feeds every night, I feel as if I have entered a Florida trailer-park version of Grey Gardens, the derelict Long Island home of Jackie O’s eccentric aunt and cousin — Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale and Edith Bouvier Beale.

“One of them is beautiful. It’s white,” Rudisill says of the ’possums. “And the other is as ugly as it can be.”

Those ’possums are an apt metaphor for Rudisill’s memories of her famous nephew. As we talk, her recollections flicker from light to dark, sentimental to sordid, tender to resentful.

While elucidating the finer points of ambrosia and sage-and-cornbread dressing, she spews shocking details about Capote’s homosexuality, his peccadilloes, his drug use, his death. Rudisill seems slighted that she — unlike other family members — never appears in his fiction. And she is vexed that her nephew distanced himself from her, that he only called when he was in trouble. Which, as it turned out, was quite a lot.

It began with Capote’s Dickensian childhood.

A pretty, epicene boy is abandoned by his cruel, social-climbing mother, Lillie Mae. He is then spoiled by his female cousins in Monroeville. In 1966, Capote publishes a book that makes him very rich and very famous: “In Cold Blood,” a “nonfiction novel” about a quadruple murder on a Kansas farm. “In Cold Blood” makes the puckish, 5-foot-4 Capote the most photographed author of his generation. It also unravels him.

When he dies 18 years later, at age 59, the sweet little boy who made fruitcakes with his cousin has become a sad, waxen caricature. In “Capote: A Biography,” author Gerald Clarke suggests that his troubled subject died of an overdose.

Rudisill believes it, too. And she remains deeply ambivalent about their relationship.

“Truman did a lot of kind things to me, and he did a lot of cruel things to me,” she tells me. “He always said to me: ‘You know I’ve got you in my back pocket, and I know you’re always there.’”

When I leave her home after about five hours of talking, I go out to my rental car and put my head in my hands — pulverized.

I’ve got a great story. But it’s not the one the newspaper wants.

And it will be a long time before I can tell it.

In the nine years after my visit with her, before she died in 2006 at 95, Rudisill became a minor celebrity.

Appearing on “The Tonight Show” to promote her second book of family recipes, “Fruitcake: Heirloom Recipes and Memories of Truman Capote & Cousin Sook,” she was such a riot that Jay Leno invited her back repeatedly.

Her “Ask The Fruitcake Lady” schtick became a regular routine. Viewers would ask her a question. She would spit back a stinging rebuke:

Susie from Cleveland: “We were thinking about sending out one of those Christmas newsletters. … Do you think this is a good idea?”

Marie Rudisill: “I have a relative that does that. And they send a letter along with what everybody in the family has done. And god, I don’t give a damn what they have done. I don’t care what they have done. … She sends that damn Christmas card every year, and it’s like a history of the family. There’s nothing more boring!”

Greg from Brentwood: “Do you think my wife would be turned on or offended if I give her a sex toy for Christmas?”

MR: “Well, my god! If you are any kind of a man at all, you don’t need to give her a sex toy! My lord, can’t you give her a good screwing every now and then? … I mean, that makes you look like a fool!”

In 2010, Atlanta-based New York Times reporter Kim Severson published her memoir, “Spoon Fed: How Eight Cooks Saved My Life.” One of Severson’s essays was on Edna Lewis, the late Southern food icon who was an acquaintance of Rudisill.

(Both Lewis and Rudisill received the Southern Foodways Alliance’s Lifetime Achievement Award, and both told me that Capote used to frequent Lewis’ storied Cafe Nicholson in Manhattan. When the pixie-ish Capote was broke and hungry for something Southern, Lewis fed him cold biscuits.)

Alas, by the time Severson met her subject, Lewis’ mind had dimmed. So Severson, for the most part, had to rely on other sources, including my Lewis obituary that ran on the front-page of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Reading Severson’s book, my mind drifted back to the afternoon I spent with Lewis at the Decatur apartment she shared with chef and author Scott Peacock. It was a day not unlike my time with Rudisill. I wondered what happened to my old taped interviews.

When I left The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2009, I stashed 27 years of old newspapers, tapes and ephemera in my garage. Nothing is more depressing to me than those boxes of old newspapers. It’s my own private morgue — replete with the sickening scent of dust and roach pills.

When I finally mustered the courage to dig around, I found the Lewis interviews — as well as a cache of other recordings. Three of the tapes had Rudisill’s name scribbled on them. I was not quite ready to listen, though. I put them in a box and labeled it.

Not long ago, as I researched a piece on pecans for Saveur magazine, I started to think about fruitcakes. So I popped one of the tapes in an old cassette player. I pressed the button and heard Rudisill’s inimitable “my god!” and “goddamn!”

I decided to keep listening. …

At a very early age, Rudisill tells me, Capote was making up stories, teasing the children of Monroeville with his magnificent creations.

She’s describing the kid Harper Lee, who lived next door, would turn into the character Dill in “To Kill a Mockingbird.” (“We came to know him as a pocket Merlin, whose head teemed with eccentric plans, strange longings, and quaint fancies,” Lee writes of her young friend.)

“He would just absolutely enthrall these children — my God! — with these wild stories he had!” Rudisill told me.

He would take kids to the door of the basement, she said, and tell them they couldn’t go down because there was a lion down there.

Rahr!

This would have been the house in Monroeville where their distant cousin Sook lived with her sister, Jenny Faulk, the family matriarch who ran a prosperous millinery shop and ruled the clan with an iron glove.

In a 2000 interview with The St. Petersburg Times’ Mary Jane Park, Rudisill said she and her four siblings — including Lillie Mae, the woman who would later give birth to Truman — moved in with the Monroeville clan when Rudisill was 5. Both their parents had died, leaving them orphans.

Jenny, Rudisill told me at her home, was a good provider but cold and aloof.

“As far as giving us stuff, we had anything money could buy,” Rudisill said. “But there was no real love or emotion in my family. Jenny, at no time did I ever see her walk up to one of us and say, ‘I love you.’ … Never! That was never done!”

You can hear the hurt and anger in her voice.

In 1924, the arrival of a baby boy — Truman Streckfus Persons — brought some joy to the Monroeville household. For some at least.

Truman’s father, Arch Persons, belonged to an upstanding Alabama family and was by all accounts a marvelous storyteller, letter writer and swindler. Rudisill believed Capote inherited his love of tall tales and his perverse gaming streak from his father.

“Everything to him his whole life was a scheme,” Rudisill said of Arch Persons. “He never made any real money. They had a miserable life. That’s why Lillie Mae kept coming back to Monroeville.”

The flitty, social-climbing mother eventually divorced Persons, who served time in jail for fraud, and later married Joe Capote, a Cuban businessman who adopted Truman, moved the family to New York City and in 1933 enrolled the young boy in the Trinity School, one of the city’s oldest prep academies.

Growing up in Monroeville, Rudisill said, Capote and Lee used to play in the yard under an enormous Lady Banks rose bush that arched over to make a little house.

Her nephew loved words from the time she could remember. He lugged around an old dictionary “big as he was.” Lee lived next door, and her father (who would become Atticus Finch to us readers and moviegoers) gave the children an old Underwood typewriter.

Under that Lady Banks rose, the future authors of “To Kill a Mockingbird” and “In Cold Blood” — Scout and Dill, if you will — would retreat into their make-believe world. “They would write and write and tell stories,” Rudisill said.

“Nelle Harper Lee was his soul companion,” she said. “I asked Truman at one time: ‘Have you ever thought about loving Nelle?’ He said: ‘I could never do that. I could never love her as a woman.’”

The great love of Truman Capote’s life may have been his cousin Sook.

She called him Buddy, and together they’d bake fruitcakes and send them off to a long list of people who had struck their fancy, including FDR. That, as many of us Southern-lit lovers know, was the source of Capote’s short story “A Christmas Memory.”

“The only person that Sook ever cared anything about was Truman,” Rudisill said. “That was because he was brought there as a baby, and she took him from the moment he was a baby, and she gave her life to him.”

His mother, on the other hand, could be vile.

“The saddest thing I have ever seen in my life. And this is not in any book. Let’s see … Truman was about 6 or 7, I guess. And in the back is where we had his tree house in that great big black walnut tree. …

“My sister had told Truman that she and Arch were coming for the weekend to Monroeville to see him. So, OK, Truman then got all excited, and he wanted to have something real nice when they arrived. We fixed this tea out in the yard, with a tea service and everything in the world like ice cream, homemade ice cream … and everything was just beautiful. Rock candy and everything that he thought that his mother would really enjoy.

“So they drove up, and they walk back in the backyard where the tea service was all laid out. … And she looked at it. And she said: ‘What is this?’ And Truman said: ‘It’s the tea. We are going to have an afternoon tea for you.’

“And she said: ‘That’s the most ridiculous thing I have ever heard of in my life!’ and turned around and walked in the house, and that was the end of that. And it just broke his heart. He just — I couldn’t bear to look at his face. Sh

e did him that way all the time. I mean, she was mean.”

Illustrations by Beth Peck

As Truman approached his 12th birthday in 1936, Lillie Mae and Joe Capote pulled him out of the Trinity School and sent him to military school for a year — an effort to try to de-gay him.

“Oh, my God! That killed him! I mean, really!” Rudisill screams to me. “Everybody told her, ‘That’s the worse thing you can do for that child.’ But she went ahead and did it anyway.”

Rudisill tells me she believes Capote would not have been gay if he had been raised differently.

“I believe this as firmly as I am sitting in this chair! And I wrote an article about it (never had it published, but I really should have had it published): ‘Are You Raising a Homosexual?’ Now I am going to tell you, homosexuals are not born. They are raised! I believe that as surely as I am sitting here. If Truman Capote had followed in the footsteps of Bud [Sook’s brother] … he would not have been a homosexual. But he chose Sook. And she used to take him to the attic and put on these things and wear high heel shoes and all that.

“I mean I really believe that! I met so many of them through Truman. You go back and it’s always somebody in that family that has encouraged him. Not that I object to it. I don’t care if anybody is homosexual. But I do think as a rule they have a very unhappy life. That’s all I care about. I worried about Truman getting beat up, which he was beat up many times and all that. I was afraid somebody would kill him. It’s an unhappy life. I don’t care how you cut the cake!”

According to her, Capote told his aunt everything about his private life. Often, she didn’t want to hear it.

Rudisill breaks down just once during our interview. It’s when she recalls “the first time Truman ever had a sexual encounter with a priest.”

She was living in Greenwich Village, having followed Lillie Mae and Truman to New York.

“He was sitting on my doorstep when I came home from work, and he had blood all in his pants, and then he told me about this priest,” she said. “And nobody, I don’t think anybody in the world ever knew that but me.”

As our conversation lurches on, Rudisill has more family secrets to reveal. Indeed, there is no one left to refute her, and she is determined to have her say.

When Lillie Mae committed suicide in 1954, a few weeks before her 49th birthday, Capote was living in Europe. Rudisill says she had to take charge.

Lillie Mae killed herself, her sister says, because the world she had created with Joe — the mansions and the mink coats — was crumbling. She couldn’t even afford to get her hair dyed.

“They lived in Greenwich, Conn., … and sent Truman to expensive schools and all that. But then he [Joe Capote] got in debt so they had an audit and discovered where he was short. And they sent him to Sing Sing. …

“I still believe, and I’ll always believe, they had this big fight that night. And she was drunk, and he knew then he was going to Sing Sing. … She knew they were going to be thrown out of the apartment and all this, that and the other. So that was the night she committed suicide.”

The night of the viewing at Frank E. Campbell Funeral Home in Manhattan, Rudisill said she received a mysterious guest.

She knew who he was. But the rest of the family refused to believe her.

The man was an “Indian” that Lillie Mae had had an affair with in Claiborne, Ala.

“See, they don’t know the real truth! I am the only person who was there! [I would] get in the car with her at 3 o’clock in the morning to go to Claiborne to meet this Indian. That was the only man in the world she ever loved in her life. I don’t care what they say. … He went to Mobile later and became a doctor. They all say there was no such person. Well, of course, there was no such person because they never went there! They didn’t know. …

“That was the saddest thing. You must understand. Back in that time, it was as bad to be with an Indian as a n***a. But she really loved him. … And I look back on it, and I think: ‘My god! I wish they could have!’ Maybe her life would have been altogether different. But how can you say that? You can’t say. But she had a tragic life, really.”

Lillie Mae wasn’t the only one in the family who suffered unrequited love. So did Truman.

But the object of Capote’s ardor was a murderer: Perry Smith, one of two men convicted of killing a Kansas farmer, his wife and two children in 1959. The story of Smith and his accomplice, Richard “Dick” Hickock, was the focus of “In Cold Blood.”

“All the time those boys were in Kansas, (Truman) made my life one hell on earth,” Rudisill said. “Because they were making his life hell on earth.”

Capote needed the men to be executed so he could finish his book. At the same time, he had become infatuated with Smith.

I ask Rudisill if the attraction was mutual.

“Absolutely, absolutely. I’ll stake my life on it. That’s all that Truman called about was Perry when he called me on the phone. …

“But he also told me this: He said, ‘Perry’s got to die, because if he doesn’t and they let him out, he will do the same thing again.’”

Smith and Hickock were executed by hanging on April 14, 1965. Moments later, Rudisill’s phone rang.

“He called me on the phone immediately, and he was just absolutely hysterical, strung out.”

In 1966, Capote celebrated the release of “In Cold Blood” with the legendary Black and White Ball at the Plaza Hotel in New York, with Washington Post Publisher Katharine Graham as his guest of honor. Capote, according to biographer Gerald Clarke, did not invite Rudisill, “who, as a result, nurtured a grudge that was never to die.”

In 1975, Esquire published an excerpt of “Answered Prayers,” the unfinished novel Capote had worked on for years. Appalled by his revelations of intimate, confidential material, his coterie of rich and famous friends, his society swans, abandoned him.

And in time, he even grew to detest Harper Lee. “Mockingbird” won a Pulitzer Prize; “In Cold Blood” did not. Capote himself may have fed the persistent rumors that he was the actual author of “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

“‘I wrote the goddamned thing.’ That was his words,” Rudisill told me. “He said he was so bitter about it because she didn’t give him any credit for anything and when he took her to Kansas [to research “In Cold Blood”], he gave her all kind of credit.”

One night in a drunken rage, Capote called Rudisill threatening to go to the press with his story. She talked him out of it.

“I said: ‘Truman, please don’t do that.’ Because I said: ‘I know you wrote it.’ I mean, I know Truman wrote it. My god!”

In 2006, Dr. Wayne Flynt, a retired Auburn University professor, reported the discovery of a letter by Capote in which he said he had read “Mockingbird” and liked it. The letter was penned in 1959, a year before “Mockingbird” was published.

Flynt told NPR’s Melissa Block: “Nowhere in the letter does he claim any involvement whatsoever in the book.”

Rudisill told me that she had no interest in profiting from Capote’s name. I don’t buy that. She wrote no less than five books that expounded on his literature and legacy.

The first, 1983’s “Truman Capote: The Story of His Bizarre and Exotic Boyhood by an Aunt Who Helped Raise Him,” co-authored with James C. Simmons, appeared a year before Capote’s death.

The book scandalized Monroeville — and Capote. He told The Washington Post: “If there are 20 words of truth in it, I will go up on a cross to save humanity."

Said Harper Lee: “I have never seen so many misstatements of fact per sentence as in that book.”

In an insightful 1983 critique in Southern Changes, the now-defunct Journal of the Southern Regional Council, reviewer Harriet Swift wrote:

The book is less about Monroeville and the shaping of a literary legend than it is about the settling of old scores. Lillie Mae Capote has been dead almost 30 years, but the wounds she inflicted on her younger sister have never quite healed. Lillie Mae, the egotistic beauty, delighted in humiliating others and her apparently eager-to-please young sister was a target too easy to pass up. The guileless Tiny even followed Lillie Mae to New York, but complains bitterly about being used and manipulated by her sister. The sins of the mother are visited in the son, who seems never to have properly appreciated all that Aunt Tiny did for him.

Swift, an Alabama native, asserts that the book is riddled with factual errors and misspellings. She calls Rudisill’s tale of Lillie Mae’s secret Native American lover one of the book’s “strangest assertions.”

During our conversation, Rudisill told me she never wanted to write another work on Capote, and offered to give me her notes if I wanted to write a book. (I didn’t.)

In 2000, three years after our visit, Rudisill published “The Southern Haunting of Truman Capote,” again with Simmons. The book purports to trace the real-life origins of Capote’s Southern fiction.

That same year, as a sort of follow-up to “Sook’s Cookbook,” she released “Fruitcake.” Shortly after, she began guesting on “The Tonight Show.”

By now she was no longer known as Truman Capote’s aunt, a description that she loathed. She was just The Fruitcake Lady.

Her final book, “Ask the Fruitcake Lady: Everything You Would Already Know If You Had Any Sense,” was published the month she died.

When I finish listening to the tapes I found in my garage, I’m more troubled than ever by my strange day with Truman Capote’s aunt.

But I have to do a little soul-searching before I can figure out why. And what it comes down to is this: I’ve always felt a certain affinity with Capote.

I grew up in the rural South, the youngest and much adored grandchild on both sides of my family. My grandmother, Nanny, was my Sook.

I spent many hours at Nanny’s kitchen table, helping her make fruitcakes, Lane cakes and Japanese fruitcakes. I played dress-up with my girl cousins, traipsing around my aunt’s boardinghouse in the tiny town of Climax, Ga. And every summer, my cousins and I would visit my Aunt Bibby and her neighbors, Miss Alice and Miss Mamie, in Cuthbert.

Those little old ladies doted on me. Their love and nurturing made me who I am today. But they didn’t make me gay.

And while my family had its share of trouble (my father took his own life when I was 12), we kept it to ourselves.

Queer relations and infidelities are not things we talked about. Certainly not to strangers. Good Southern families didn’t do that.

I can’t imagine one of my father’s siblings besmirching his memory. Never! Or an aunt whispering unkind sentiments about me. Not for a second!

Too much love there. Too much pain.

So I understand why Capote was upset by his aunt’s account of his “bizarre” and “exotic” boyhood.

It wasn’t what she said about him, Clarke wrote. “What disturbed him more was her malicious depiction of his mother.”

Clarke also asserts that a short story published by Rudisill under Capote’s name after his death was a fake. Called “I Remember Grandpa,” it appeared in 1985.

When I spoke to Rudisill, she said that Clarke’s claims about the story’s inauthenticity had sabotaged her writing career. She insisted that “I Remember Grandpa” was a better story than “A Christmas Memory.”

“Read it!” she screamed. “It is!” (I did, and it’s not — by a long shot.)

Though Capote suffered emotional problems for decades, Clarke contends that his subject’s downward cycle escalated after Rudisill’s scathing memoir.

When I read Clarke’s account of Capote’s last moments, I am moved to tears.

Capote may have been holed up in the California home of Joanna Carson (ex-wife of “The Tonight Show” host Johnny). But in his soul, he was in Alabama.

He was returning.

And at the very end, Carson told Clarke, he murmured: “It’s me. It’s Buddy.”

It’s as if he was speaking to Sook.

If Rudisill is lucky, history will be gentler on her than she was on her nephew.

John T. Edge, director of the Southern Foodways Alliance in Oxford, Miss., believes that Rudisill’s “Sook’s Cookbook” was an important contribution to Southern food.

“If she is remembered 50 years from now, I think it will be for that book,” Edge told me. “Not for Jay Leno. Not for wisecracking about sexual innuendo. But for that portrait of that place. Not that book as a companion to Truman Capote’s writing but that book as a standalone piece.”

Edge also loved Marie Rudisill for the kooky character that she was. We all did.

“I appreciated her as actor in the Southern pageant,” he said. “She had a role to play and she knew it and she nailed it.”

Racist, homophobic, whatever. I’d be lying if I said Rudisill didn’t make me laugh. Listening to those tapes, I wanted to call her up to say hello.

After all, I owe her for one of my favorite Christmas memories.

Just before Christmas in 1997, after my tame, family-newspaper version of the story ran in the AJC, a package arrived at my house. Inside was a small plastic container with the letters “MR” scrawled on the lid.

Inside that: A wedge of fruitcake.

When I opened that little container, I could hear Rudisill talking.

“I tell you the most fantastic thing about Sook and her cooking was her fruitcakes. Really I am not kidding! I mean really! You have no idea! No, you don’t.”

But right then, thanks to her, I did.

Marie Rudisill's Fruitcake Recipe

We asked our friends at Tiny Buffalo Baking Co. to reinterpret Marie Rudisill’s coconut fruitcake. Tiny Buffalo owner Audrey Gatliff obliged with a beautiful piece of bakery art.

“Rude as Hell” Eggnog

We asked Atlanta’s masters of punchbowl drinks, the barkeeps at H. Harper Station, to update the Fruitcake Lady’s “Real Plantation Eggnog.” Perhaps, with the update, we’ll never have to use the word “plantation” again.