Andrew Howard Brannan was the first person to be executed in the United States in 2015. Years before, he had been a decorated Vietnam veteran, but one who came home to Georgia with deep post-traumatic stress disorder. Then one night in 1998, Brannan killed a deputy sheriff. Today, we begin a two-day series by veteran journalist Pate McMichael, who follows the life of Brannan from childhood to death row, where he spent 15 years waiting to become the last casualty of the Vietnam War.

By Pate McMichael

Deputy Sheriff Kyle Dinkheller was about to become Georgia’s Officer of the Year for Valor. He was patrolling the westbound lane of Interstate 16 as it enters Laurens County, a remote stretch of Middle Georgia farmland and pine forest that connects Macon to the west and Savannah to the east. His shift ended at 6 p.m., and Angela, the mother of his infant daughter, Ashley, made him promise to run an important errand after work. One more traffic stop and he could start for home.

Dinkheller joined the sheriff’s department as a jailer. He was promoted to patrol officer a few weeks after his 21st birthday, earning $500 every two weeks. This more dangerous assignment meant that he now carried an AR-15 rifle to go along with a Glock automatic pistol. He averaged 15 citations a day and 10 arrests per week: outstanding warrants, drug possession and DUIs. On New Year’s Eve, he apprehended a missing person and logged it in with exclamation points.

Today had been more routine, a classic Monday, until 5:38 p.m., when a white Toyota Tacoma clocked in at 98 mph headed east. A less committed officer might have just let it go.

Dinkheller’s cruiser crossed over the grassy median just as the Tacoma bolted off the Highway 338 exit. He didn't immediately notice, then did, and missed the exit. Clear of the underpass, the cruiser fishtailed back across the median, taking the westbound exit onto Highway 338. Ahead, the Tacoma turned right on Whipples Crossing Road, but Dinkheller closed the gap with his dash-mounted blue lights flashing. The Tacoma pulled over.

“Driver, step back here to me,” the deputy demanded. “Come on back here for me. Come on back. How you doin’ today?”

A sullen middle-aged man with a scraggly beard emerged from the truck and approached menacingly. He wore a baseball cap with big-rimmed glasses and an Army field jacket with fatigue pants. Suddenly, he shoved both hands into his pockets.

“Come on back here and keep your hands out of your pockets,” the deputy warned, fingering his sidearm.

“Why?”

“Keep your hands out of your pocket, sir. Sir!”

“Goddamn it, here I am. Shoot my fuckin’ ass!”

In a bizarre rage, the driver then danced in the middle of the road, flailing about with both arms and taunting: “Here I am! Here I am!”

“Thirty-seven radio 10-78,” Dinkheller barked into his radio.

“Who are you calling, motherfucker?” the driver yelled, charging aggressively into the deputy’s space.

“Sir, get back, now! Get back!”

The driver charged again, and Dinkheller, while standing his ground, refused what would have been justifiable force.

“What are you doing?” the driver yelled.

“Sir, get back!”

“No! Fuck you!”

“Sir, get back! Sir, step back!”

“I am a goddamn Vietnam combat veteran and I am not going to…. Fuck you!”

The driver returned to his truck, cursing and pointing in a threatening manner. Dinkheller started to follow but then bailed to the rear of his cruiser. For 20 brutal seconds, the driver rummaged around inside the Tacoma while the deputy barked futile commands in a panicky voice.

“Sir, get back! Get back now!”

“What? I am in fear of my fucking life!” the driver screamed, searching anxiously.

“I’m in fear of my life! Get back here now!”

“No!”

“Step to where your vehicle — put the gun down!” the deputy pleaded. “The man has a gun. I need help. Put the gun down! Put the gun down!”

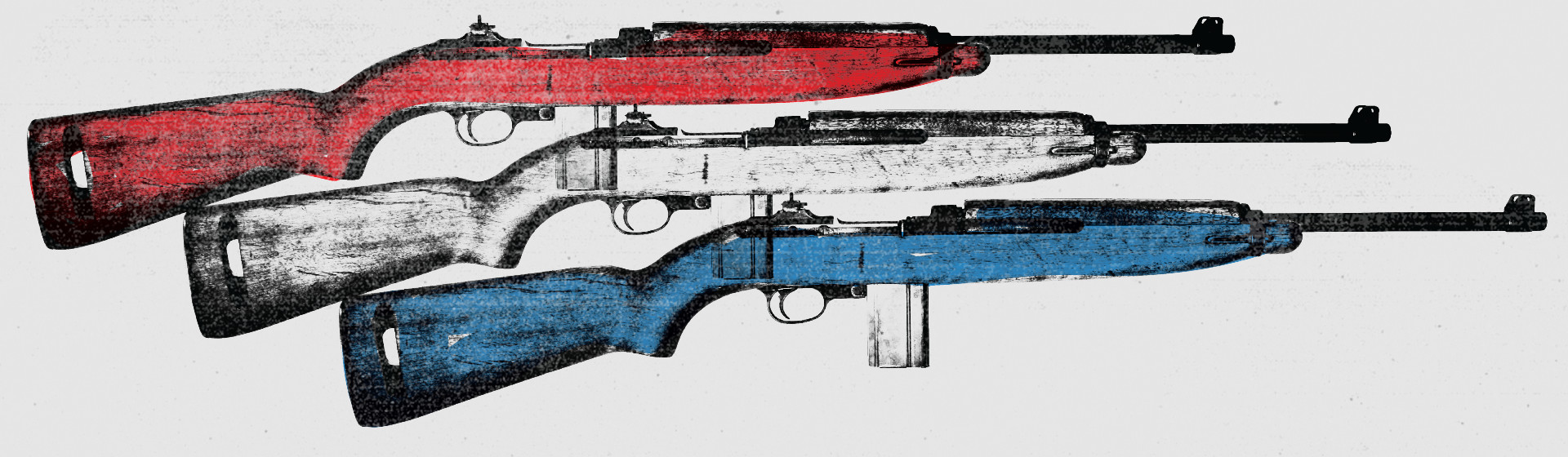

The driver stood in the pocket of the truck door, training an M-1 carbine, fully cocked, on Dinkheller, who had taken up a firing position at the rear of his cruiser. A harrowing silence ended when the deputy fired first.

The driver, unscathed, returned fire, splintering the cruiser’s windshield. He ducked to reload, just as a bullet exploded the window above his head. He stood up and advanced, cutting his way over to the passenger side of the cruiser and firing methodically. A terrible scream, followed by heaving breathing, came from Dinkheller, who was now firing from the pavement.

Having the advantage, the driver returned to the front of the cruiser before charging in for the kill. Dinkheller, with blood in his lungs, fired again, before letting out another awful scream as more bullets tore into his body.

The driver was hit by one of the deputy's last few rounds. He stepped back and touched the wound, then rushed forward in anger to fire twice more — execution style.

“Die, fucker!” the driver yelled, before jogging back to his truck and fleeing the scene.

A large, mixed-breed dog named Moses survived the shootout. He was riding shotgun in the killer's truck when it stopped at a primitive camp house just minutes from where Deputy Dinkheller lay dying. The structure was three stories of plywood, accented by a crudely built porch and giant tarps that covered the unfinished sections. There was no landscaping to speak of, just a few deep holes along the periphery that looked like firing trenches. The third story amounted to a vertical shoot with two windows, either a church steeple or a sniper's nest. The killer, Andrew Brannan, 49, was the architect and builder.

Brannan was gut-shot. Soaked to the skin in blood, he limped out of the truck, leaned the carbine against a post, then grabbed a tarpaulin and staggered off into the woods, where he collapsed. Helicopters circled overhead and tracking lights flashed through the trees as Moses followed behind, barking incessantly. Brannan tried to fall asleep, but Moses licked his face and barked through the night.

Just after dawn, law enforcement raided the cabin and surrounding forest. Police dogs picked up a scent and followed it down a wide trail to a big tree. Brannan was still there, his wounds clotted by the cold. Arrested but unharmed, he walked out of the woods at gunpoint while a team from the Georgia Bureau of Investigation combed the property, seizing a damning amount of evidence, including a stash of pot and a worn copy of Machiavelli's “The Prince.”

An ambulance took Brannan to a hospital in the county seat of Dublin. He was handcuffed to the bed awaiting surgery when two Georgia Bureau of Investigation agents suddenly entered. Eager to talk, Brannan waived his right to a lawyer and took responsibility for the crime.

"They can kill me. They can shoot me in the head. They can hang me from the nearest tree," he confessed, pinning his guilt on a two-week lapse in medication and the intricacies of mental illness. Put it together and he just snapped. “I’m a disabled veteran. I’ve had PTSD all my adult life,” Brannan said. “I have a mental disorder and I don’t seem to be able to do much about it except, you know, take the medications the VA tells me to take.”

The GBI kept him rambling. Almost every sentence was punctuated with an ill-timed, nervous laugh. “I know some people get offended by it, but it’s just, instead of crying I laugh like that,” Brannan apologized. "There have been about a hundred thousand Vietnam veterans commit suicide with PTSD and stuff. And I just — I didn't want to commit suicide. I felt like I had a responsibility to stay alive somehow."

The agents did not mention the dash camera in the deputy's cruiser nor the audio from Dinkheller's microphone. Unaware, Brannan lied in saying that he did not pull his weapon until after the deputy fired the first shot, when in fact he pulled his weapon first, giving Dinkheller no choice but to fire first. He denied executing the deputy while he lay defenseless and wounded, calling the victim “foolish” and “young” for drawing his gun so quickly. “Y’all need to work on your techniques,” Brannan advised. “I was trying to get to my land so that I would be away from folks.”

After surgery, Brannan was transported to Baldwin County, 45 minutes north of Laurens in close proximity to the state mental hospital. He was incarcerated at the county jail, a crowded facility where inmates defecated publicly. As months turned into years, Brannan started to crack. Jailers put him on suicide watch after finding two razor blades and a braided plastic rope under his mattress. On several occasions he refused or hid medication, leading to mania. One evening, as another prisoner started to enter his crowded cell, Brannan blocked the door with clenched fists.

“I’ll go to the hole before anyone else comes into C-2,” he threatened a guard.

The trial was two years in the making, but hardly forgotten in Laurens County, a rural, overwhelmingly Christian community of 40,000. Townsfolk and law enforcement kept faded stickers on their windshields that read: “Remember Dink!” So much evidence had been relayed by local media that Superior Court Judge William Towson moved the trial two hours away to Brunswick, a coastal Georgia town that's also home to a federal law-enforcement training facility.

Brannan's family retained Richard Taylor, an Atlanta defense attorney with ties to Laurens County. After graduating from Mercer Law School in nearby Macon, Taylor clerked for Judge Towson, the trial judge. Taylor had also worked for the district attorney, Ralph Walke, back when Walke headed up the county's public defender team.

Despite those connections, Taylor failed to reach a plea. He begged and badgered, even warning his old boss about getting overturned on appeal. Brannan had no criminal record, no documented history of violence besides his tour of duty in Vietnam. Taylor passed along research about his client's mental disorder with titles like “Malignant Post-Vietnam Stress Syndrome” and “Continuing Readjustment Problems Among Vietnam Veterans.” He cited Supreme Court cases outlawing the execution of defendants found to be insane at the time of the crime. When that didn't work, he lobbied the county commission with statistics showing that a death penalty trial would cost taxpayers at least $200,000.

Nothing came of it. Laurens County wanted Brannan’s scalp. When the trial began on Jan. 25, 2000, the state used jury selection to strike seven of 11 African-Americans, who traditionally do not support the death penalty, in favor of whites vocalizing strong conservative values, including a no-nonsense Marine who served in Vietnam. When asked his opinion of PTSD, the Marine replied, "I ain't never had the problem with that." The defense ultimately put three African-Americans on the jury, but the one Taylor needed most, another Marine who also served in Vietnam, was struck by the state when he admitted knowing soldiers suffering from PTSD who would "freak out" and "snap."

The trial started on a Monday and ended Jan. 30, a Sunday morning. Brannan pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity, and Taylor put his client's mental illness on trial, arguing that the confrontation with Deputy Dinkheller triggered a PTSD-induced flashback, making his client incapable of knowing right from wrong. Brannan entered into a transient, psychotic, dissociative state that spiraled horribly out of control. Throughout that murderous rage, he thought he was back in Vietnam.

Taylor explained that Brannan deployed in the fall of 1970. As a forward observer, he spent months at a time in the field, witnessed comrades die in battle, and assumed a heavy guilt over their deaths. The Department of Veterans Affairs knew nothing about PTSD, but over time, as more veterans returned home unable to readjust, VA psychiatrists found themselves overwhelmed with an epidemic.

The medical records showed that Andrew's "head had never really gotten out of the service." He suffered from PTSD and severe depression, afflictions that progressed, in tandem, with personal tragedies and professional setbacks. Embarrassed by his instability, Brannan fled the civilized word and took refuge in the wilderness. From 1985-1989, he hiked thousands of miles along the nation's most challenging trails. He hiked the Appalachian Trail and the Pacific Crest Trail. He hiked the Olympic National Park Trail and the Wonderland Trail. He did not receive in-patient treatment for PTSD from the VA until 1989 — nearly two decades after returning from Vietnam.

The court-appointed psychiatrist, Dr. Gary Carter of Central State Hospital in Milledgeville, accepted Brannan’s PTSD diagnosis but did not agree that he was temporarily insane at the time of the murder. Dr. Carter interviewed Brannan five times, then filed a report to Judge Towson stating nine reasons why Brannan was not in a flashback. The fact that Brannan fled the scene and drove directly to the camp house was the most convincing. If Brannan thought he was in Vietnam, how could he so quickly reconnect with reality and prepare such a rational escape?

Dr. Carter overlooked the fact that Brannan had been diagnosed as psychotic. The defense shamed him on the stand, then fielded testimony from a forensic psychologist named Richard Storms, whose impressive resume included a stint at Central State. Storms concluded that the Brannan experienced a psychotic flashback, if only for a few fatal seconds. Storms felt certain that Brannan was not malingering, the clinical term for lying, because he downplayed the severity of his mental illness. Those who malinger do the opposite: Try to convince you they are very sick. Another decorated psychologist, Avrum Weiss, supported Storms, not Carter. Brannan's anger triggered a flashback, Weiss testified. He lost the ability to distinguish right from wrong.

Prosecutors mocked the defense for relying on academics (psychologists) over medical professionals (psychiatrists) like Dr. Carter. Walke called Storms and Weiss "hired guns" who show up "30 miles from home with a briefcase" to "muddy up the water." Shouting with dramatic flair, assistant district attorney Craig Fraser repeatedly questioned the legitimacy of PTSD as a medical diagnosis. “I walk into a Kentucky Fried Chicken," Fraser told the jury in closing. "And I smell that chicken frying, and I say, you know, that smells so good, and I can see my mama standing over there frying me chicken early this morning. Am I having a flashback to my mama in the kitchen?”

District Attorney Walke also got into the act. "How many rice paddies you reckon he passed while he was driving his Toyota pickup truck down I-16? I bet when he was in Vietnam the Viet Cong attacked him regularly driving marked Crown Victoria Ford patrol cars with 'Sheriff' written all over the side and blue lights flashing."

The jury was led to believe that Brannan faked his mental illness after the war to live off hard-working taxpayers. “He got to studying it and he got himself a 10 percent disability,” Walke claimed. “And he worked a little harder and he got it up to 30 percent. And then after his mama cut off his money while he was going on hiking trips, he finally got all the way up to 100 percent.”

The state never settled on a motive, but relied instead on replaying the murder tape. Prosecutors painted Brannan as a cold-blooded killer who demanded respect for his service like "when Lucifer was kicked out of heaven and became the Devil." They described his combat experience as unexceptional and unrelated. “Vietnam had not one thing in the world to do with this murder,” Fraser said. “That is a flimsy, sorry, no-good, stinking excuse.” The state also suggested that Brannan might have killed the deputy because of "marijuana in his blood, pipes in his house."

The jurors handed down a guilty verdict just before midnight on Friday. The next morning, they hastily considered testimony from friends and family as part of the sentencing phase. Brannan's fate was sealed when Dinkheller's widow, Angela, took the stand and broke the jury's heart.

"Kyle was supposed to bring home the pregnancy test the night he was killed," she said. "So, I found out I was pregnant for sure two days after we buried him.”

Angela named their son Cody. "I’m the one who has to take these babies to a cemetery and try to tell them that this is where their daddy is now," she continued. "I’m the one who a good part of has died right along side of Kyle that night. And still am expected to raise those same babies the best I can, without him, pretending everything will be OK, so not to upset them.”

On Sunday morning, around church time, the jury sentenced Andrew Howard Brannan to death.

Before her last living son killed Deputy Dinkheller, Esther Brannan, 77, attended a board meeting for a cancer charity. Then she came home for lunch to find Andrew and Moses in the backyard; Andrew was treating landscape timbers for termites. When not outside doing yard work, Andrew built computers in his bedroom, studied software systems, and played the stock market. Every four weeks he drove to the VA in Decatur for counseling and doctors' visits.

The camp house in Laurens County was Andrew's way of fleeing the sprawl of Atlanta. The honest work of building what Esther called his "retreat" seemed to give him a sense of purpose, but it did not yet have power, just a generator, so she prepared enough food to last for several days, then sent him off at 3:30 p.m. with a kiss. That evening she attended a city council meeting, and returning home after dark, found a police cruiser waiting in the drive. The security system must have gone off again, she thought.

As Andrew lay gut-shot in the Laurens County woods, Esther told the GBI that her son was "very remorseful over sending soldiers into battle to die." He was exposed to Agent Orange and goes through "spells where he gets very upset and screams." He might "kill himself rather than go to jail" because of a family history of depression combined with the severity of his mental illness. She said Andrew had recently visited a friend in Nevada and returned with a weapon to scare off crows at the retreat. She blamed herself for allowing him to keep the rifle, then provided the names and phone numbers of people he might try to contact, including the friend in Nevada. As she gave her statement to police, the GBI tracked Andrew and his Tacoma to the camp house.

Two years later, as the jury decided Andrew's fate, Esther recited a note she penned to Dinkheller's family shortly after the crime. "This is the hardest thing I have ever tried to write, but I want you to know that I am so sorry for the suffering you are now going through," the letter read. "I know that I can't ask for forgiveness."

For three decades, the Brannans had lived in that modest brick home raising three sons and several grandchildren. Few families in Stockbridge commanded more respect. Esther's late husband, Bob, grew up in a big family on a Henry County farm and pulled himself up from poverty — by the bootstraps. He joined the National Guard out of high school and later served his country in two wars. In the mid-’60s, he retired as a lieutenant colonel, war hero and Legion of Merit recipient.

Never one to rest on his laurels, Andrew's father entered college and earned a bachelor's in education. He taught for the first time at age 50, then completed a graduate degree to serve in administration. His first assignment as a principal was to help integrate a public middle school. Friends who knew him best respected his humility, his capacity for leadership and his willingness to compromise when folks didn't see things his way. He was never late, and he never held a grudge.

Esther was his better half, sharp and pretty, devoted and direct — the perfect wife for an officer. She was from a big family in nearby Jackson — the Middle Georgia town where the state performs executions. She married Bob in 1940, just before he received a promotion to sergeant. A photograph of Bob's pregnant wife stepping off a train in Sendai, Japan, at 7 in the morning ran in Stars and Stripes, the military newspaper, during the fall of 1953. Her husband had just returned from another deployment to Korea, so she and several other families were escorted to the officers' club at Camp Schimmelpfennig, greeted by the general, and serenaded by a band playing "Together." In 26 years of military service, they moved 27 times.

No matter the theater, Esther found a way to turn barracks into bedrooms. She kept the boys on a rigorous regimen and served hearty meals that made them strong. She gave orders, took names, and demanded respect. The Brannan boys attended military academies away from home to improve self-discipline. After earning a college degree, each was expected to enter some branch of the Armed Forces as an officer. Bob believed that climbing the ranks without higher education was a thing of the past.

The plan failed, miserably. The oldest son, Bobby, skipped college to fight in Vietnam. Trained as a helicopter gunner, he was gung-ho, well-liked and daring. In 1965, he brought home a North Vietnamese battle flag pillaged off one of his kills — and a Purple Heart. A few years later he became an officer, earned his wings, and did another tour in South Korea, where like his father, he flew dangerous patrols and survived a crash landing.

People in Stockbridge knew Bobby as the gregarious daredevil who liked to buzz his friends' apartments or wave his wings at pretty girls. He was the kind of guy who would shove off on a Friday, fly his Cessna to Cumberland Island, the gem of Georgia's barrier islands, to spend a weekend camping on a desolate beach. Esther and Bob doted on him, even after he moved out, married his Army secretary, and fathered three little girls. In the fall of 1975, they were stationed at Letterkenny Army Depot in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, when the brass came knocking unannounced: Bobby's plane had gone down in bad weather near Gage, Oklahoma. One mile short of the runway, the plane crashed into an alfalfa field. He had volunteered for the mission at the last minute, as a favor to a friend. Bobby died at age 32.

His death came the year after Sam, the youngest son and best-looking Brannan, also joined the Army straight out of high school. Vietnam was over, and Sam discharged honorably in 1979 without combat experience. He married a beautiful woman from a prominent Atlanta family and fathered a son. Soon after, it came crashing down. His wife filed for divorce, leaving Sam despondent and aimless, unable to hold down a job or stay away from the bottle. Neither Bob nor Esther could reach him as depression and drinking took control of his life. Sam finally drove out to his father's ancestral land in Henry County and carved his ex-wife's name into a tree. Then, he got back into the car and sat patiently as exhaust fumes took away the pain, committing suicide at age 31.

The traumatic nature of Bobby and Sam's deaths always bothered Esther and Bob, but they were too dignified to grieve in public. Privately, they wanted to know more but found few answers, except through their Methodist faith. Esther held herself together by working at the bank and doing community service. Bob taught flying at Berry Hill Airport. Often, he could be found in the hangar celebrating a pupil's first solo, or sharing stories about his combat tour in Korea, how he survived freezing-cold sorties in a spotter plane and returned to base with bullets shot clear through his fuselage. Korea was a "bloody, terrible war," he liked to remind young people.

In 1990, Bob was diagnosed with prostate cancer. Esther lost him three years later. The funeral was held at Stockbridge First United Methodist Church, where Bob taught a popular Sunday school class for decades. Hundreds of mourners sang "America the Beautiful" and "How Great Thou Art." The colonel was laid to rest in East Lawn Cemetery in the company of two veterans — his sons Bobby and Sam.

Andrew was Bob and Esther's typecast version of the middle child. His brothers took the bookends of personality and beauty, leaving Andrew overshadowed and in between. He was shy and serious (an early-age watch wearer) but also wild about sports cars and rock and roll. In the summer of 1967, he enrolled at West Georgia College as a history major, just in time to witness a sitting president — Lyndon Johnson — give up the office over an unpopular war.

Vietnam had evolved into a killing machine. The draft showed no signs of letting up, so after two mediocre semesters, Andrew put down his books on the gamble that Uncle Sam needed officers more than grunts. It worked out. He earned his gold "butter" bar at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, then trained as a forward observer at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, jumping out of planes, studying artillery systems, and learning to read jungle maps. He was 21 years old, baby-faced and able-bodied, the proud new owner of a sporty M.G.

In the summer of 1970, Lt. Brannan deployed to Vietnam assigned to the Americal Division, which operated out of a giant coastal military base in Quang Nam province called Chu Lai. The base (typically pronounced "MER-cal" by its soldiers) was a blinding beach of sandy roads and sandbags, a seaport with landing strips and passenger terminals. Mess halls were the size of chicken houses, stacked between hundreds of A-frame hooches. Everything was painted Americal blue, even the plywood latrines and spent fuel drums.

Lt. Brannan's first week amounted to a stand-down in the chow line — but he had no appetite. To keep soldiers from heat stroke in the field — temperatures climbed as high as 130 degrees Fahrenheit with high humidity — the Army held them on base for several weird days. The contrasts and inconsistencies were shocking. As blood-spattered surgeons in the Chu Lai M.A.S.H. operated throughout the night, the general took boozy, gourmet meals in his air-conditioned private quarters. Officers screened movies, sipped ice-cold beer, and held weekend barbecues along the beach while corpses were offloaded on base, flag-draped, and repackaged for home delivery.

Flying out into the field, Lt. Brannan watched as the city of shacks and shanties built around Chu Lai dissolved into a patchwork of triple canopy jungle, stream-fed rice paddies and well-timbered mountains. Twenty-three klicks south of Chu Lai, the lieutenant from Stockbridge finally landed across the Ham Giang river in Quàng Ngãi province. He arrived at LZ Dottie, a remote, hardscrabble, red-clay landing zone ringed in barbed wire and protected by land mines.

Dottie resupplied men in the field but also served as a firebase for heavy artillery. She had something of a past. The base was home to the Americal's First Battalion, Sixth Infantry — better known as the 1/6 Gunfighters. Two years earlier, Charlie Company left Dottie at dawn, landed in an area they called Pinkville, and commenced the slaughter of 500 innocent civilians, mostly women and children.

Details of what became known as the Mai Lai massacre had roiled the nation and slandered the 1/6 as a battalion of "baby killers." Congressional hearings and military cover-ups filled the nation's newspapers as Lt. Brannan, who was technically assigned to an artillery battalion in support of the 1/6, inherited Charlie Company's folly. Lt. Brannan commanded a small squad of four men from B Company, including a radio operator, and they specialized in reconnaissance, humping it along the same seaside lagoons, dried-up patties and well-tunneled rock outcroppings, through the same tiny villages where women and children had been indiscriminately slaughtered by Charlie Company. "This is a bad place to be," Lt. Brannan wrote home in August. "There are many boobytraps and mines."

Lt. Brannan and his small team patrolled down range for weeks at a time, usually 60 days straight, on search-and-destroy missions. They operated in the sightless night in hopes of capturing the enemy alive and gathering intelligence. They survived on C-rations ferried in from Dottie by helicopter. They slept on the ground, usually during the day, in a heightened state of alert because the enemy, elusive and unseen, loved to ambush with sniper fire. When appropriate, they called in airstrikes on enemy positions using grid coordinates. On quiet days, when the sun came out, soldiers would sometimes lay strung out in a hedgerow trying to unbuckle their stomachs by playing cards and sleeping off fatigue.

"I have dysentery or something. I have been feeling bad for a few days," Lt. Brannan wrote home at the end of summer. "We have a very good medic. He was keeping good care of me and everyone else, but he hit a mine this morning on patrol."

The hardest months were in the fall when monsoons lashed the coast and brought in the rainy season. Getting resupplied from Dottie sometimes took days, and the rice paddies filled up with water, making patrols more perilous because the routes became more predictable. Platoons waded through fast-moving currents and ghastly swamps, then tried to sleep soaking wet in mud puddles on empty stomachs. Every day was a miserable, exhausting slog that rotted your feet — literally — and filled your lungs with fluid. The dinks, as most soldiers called the enemy, didn't seem to mind. Every few days they'd lay an ambush or burst through the lines firing on automatic, then chunk in a few grenades. It usually ended with dead dinks and American limbs lying prostrate in the mud.

Once or twice in a given tour, the brass would grant the men a two-day stand-down back at Chu Lai. These celebrations of life and death were defined by hell-raising and hangovers, long periods of sleep and hot showers. Exotic dancers and live bands arrived from Thailand or South Korea, and soldiers crowed with ecstasy as the women undressed on stage. Men under Lt. Brannan's command liked the fact that he'd break protocol and buy you a pint of liquor on a stand-down. They liked the fact that he'd also question bullshit orders in the field — to his own detriment.

Lt. Brannan turned 22 in the muddy hell of Vietnam on November 26, 1970. "We were to come in from the field for a few days of rest on the 26th," he wrote, "but they just gave us another area of operation that starts the 26th so I guess I will be in the field on my birthday. Please send my checkbook so if I ever get to go on R and R in December I will have some money."

Officers served six months in the field, then six more in the rear. Lt. Brannan had a few days left on patrol when the war suddenly stole the eerie calm of the past five months. When first deployed, he had expected to be terrified to the point of paralysis. It shocked him to learn that he could stuff down the fear, night after night, and keep his head clear during combat. At least he felt that way until the afternoon of December 6, when his team linked up with another squad led by his commanding officer, Capt. Roy Shaw.

They were positioned on a hill along the coast with a mortar platoon. Someone spotted dinks in black pajama pants 500 yards away. A firefight netted one kill, plus the capture of a female North Vietnamese soldier. She was interrogated before the dustoff ferried her back to Dottie. Armed with good intelligence, Capt. Shaw split the teams, assigning the second half to Lt. Brannan. They forked off, in dense foliage, when a large explosion shook the ground.

The smell of burning flesh was unmistakable. Lt. Brannan walked point to the blast site, where two soldiers, disfigured from shrapnel, were hemorrhaging and screaming in pain. The radio operator called in a dustoff and performed triage on the wounded. The smoldering corpse of Capt. Shaw, who triggered the blast, received little attention. The captain's legs were blown off into a rice paddy, his flesh burned to the bone. He died instantly. Full circle, the dustoff evacuated his remains, alongside the wounded, back to the Chu Lai M.A.S.H., where new recruits had just arrived for their own stand-down in the chow line.

Lt. Brannan assumed command of the company. He cleared the area, led his men out of the bush, and blamed himself for the deadly trap. Superiors later awarded him the Bronze Star for doing "an outstanding job in a combat environment" and commendation medals for "controlling and adjusting artillery fire in close support of an infantry company under combat conditions in a counter-insurgency environment." He was promoted to first lieutenant, then spent the last six months of his tour in the rear — unpacking what the hell had just happened.

Come back tomorrow for the second installment of “The Last Casualty,” when we follow the life of Andrew Brannan from his homecoming from Vietnam to his execution, 35 years later, for the murder of Deputy Sheriff Kyle Dinkheller.