There is the South. But there is also“the South” — the version of our region conjured by television executives. Today, Gabe Bullard takes a hard look at the weird history of hillbilly TV, from Andy Griffith to “Duck Dynasty.”

Story by Gabe Bullard

Don Knotts, Andy Griffith, and Jim Nabors: aka Barney, Andy, and Gomer.

On February 23, 1971, America had a televised identity crisis.

Just before 9:30 p.m., on CBS, Buck Owens and Roy Clark led the cast of “Hee Haw” in the same singalong that closed every episode — “May your days be bright, may your thoughts be light, ’til we meet again” — before signing off, “We’ll see you next week, right here on ‘Hee Haw’!”

Cue the banjo, the shots of the cast laughing, the women in gingham dresses, the men in plaid shirts and bib overalls, the cartoon donkey rolling its eyes around and around. Fade out. A few ads and . . .

Fade up on Archie and Edith Bunker sitting at their piano in Queens, singing in a new episode of "All in the Family."

Boy, the way Glenn Miller played

Songs that made the hit parade,

Guys like us, we had it made,

Those were the days ...

It had been like this all month. CBS went from its silliest show to its most satirical — "All in the Family" talked about race and sex, "Hee Haw" had rubber chickens. But this time, there would be no next week for “Hee Haw.” It was canceled, along with two shows that had aired earlier that night, "Green Acres" and "The Beverly Hillbillies." By 1971, all the other rural-themed CBS shows were headed for cancellation or already off the air: "Mayberry RFD,” “The Jim Nabors Hour,” “The New Andy Griffith Show," “Petticoat Junction” and “Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.” In their place, CBS would put more shows like "All in the Family," and "Mary Tyler Moore." The ’70s were to be a decade of realism and relevance on TV the same way the ’50s had been a decade of Cold War suburban idealism.

In between, television went South.

The "Hee Haw" gang.

When the newscasts were full of footage from My Lai and Saigon, from Selma and Birmingham, Americans looked for laughs in Hooterville. They sought them in Cornfield County, Pixley, and Mayberry. These were fictional rural places full of carefree, unencumbered country folks. There was no racial strife in these burgs because everyone was white. In these worlds, the sheriff didn’t carry a gun, a man could join the Marines and never talk about the war in Vietnam, and nobody even thought about the War on Poverty.

“Rural America was like true America: simpler, without all the problems of big city life, technology, the Russians, and that kind of stuff,” says TV historian and former executive Tim Brooks.

CBS did not invent the idea of using the South as a foil for modern life, but the shows it aired streamlined the concept for television. The combination of old stereotypes and mass media created an alternative "South" that combined all of rural America into a single land of silliness, simplicity, and safety. And it put an exaggerated idea of the white working class at the center of everything.

Now, it was ending. Critics soon nicknamed the mass cancellation of escapist Southern shows "the Rural Purge." Variety reported CBS was trying to “shake the hayseed out of the primetime schedule.”

It wouldn’t be that easy. CBS’s Southern expedition was a hit. In nine out of the 10 years of the '60s, at least one of the network’s rural comedies had been among the five highest-rated programs on TV. Canceling them meant turning away millions of fans who had grown to love TV’s idea of their country and its past. While the Rural Purge could take the shows away, it couldn’t end the allure of the world they created.

Like Granny used to say about the South on “The Beverly Hillbillies,” this imagined America would rise again.

The CBS rural revolution had started 11 years earlier — on the day after Valentine’s Day, 1960, on a sitcom typically set in New York.

On "The Danny Thomas Show," Thomas gets pulled over while passing through North Carolina. Short-tempered, he fights the "hayseed" sheriff of this "hicksville" town over a moving violation. The legendary comedian Thomas is the star, but most of the episode follows the sheriff as he goes about his life: He visits with his aunt and talks with his young son. Soon, the sheriff had a show of his own on CBS, and it was beating Thomas in the ratings.

Andy and Opie down at the fishing hole.

The episode “Danny Thomas Meets Andy Griffith” had been a test for a sitcom featuring Griffith, then a rising star. Its producer saw the potential for Griffith on TV, and he knew rural shows were becoming a safe bet on television in 1960. Each of the Big Three networks had at least one popular western, and “The Real McCoys”— a sitcom (co-produced by Thomas) about a West Virginia family that moved to a farm in California — was popular on ABC, which bought the show after NBC turned it down.

The McCoys and the people of Griffith's TV hometown of Mayberry each brought elements of a long-established stereotype of rural characters to television. They're living in modern times, but they have a simplistic, wiser way of life achieved through a rejection of outside agitation — like, say, passing comedians — and inextricable from its rural setting.

The rise of this entertainment in the '60s “speaks to uncomfortableness about modern urban society,” says Anthony Harkins, a historian, and author of the book “Hillbilly: a Cultural History of an American Icon.” The hillbilly stereotype, Harkins writes, has “served at times of national soul-searching" when "modern Americans have attempted to define themselves and their national identity and to reconcile the past and the present."

This nostalgic rural idealism is clear from the earliest moments of “Danny Thomas Meets Andy Griffith.” Thomas blows into Mayberry in a big hurry to get to the big city, and he’s baffled by how out of place he is. He’s a contemporary complication in an environment that’s almost magically charismatic and carefree.

If Thomas had been passing through the real North Carolina in February 1960, he’d have driven close to Greensboro, where lunch counter sit-ins had just begun.

In 1957, three years before he was Andy Taylor, Andy Griffith was the alcoholic Arkansas drifter-turned-demagogue Lonesome Rhodes in Elia Kazan’s film “A Face in the Crowd.” Rhodes is a sort of anti-Griffith, who uses his folksy and unpredictable persona to climb from the drunk tank to national television. Off-camera, he calls his fans “rednecks, crackers, hillbillies.” On air, he’s one of them. “Lonesome Rhodes is the people! The people is Lonesome Rhodes!” he proclaims. The movie is a dark take on the power of television.

Also in 1957, “The Nat King Cole Show” ended after three years on NBC without a national advertiser (and after not being aired by some affiliates in the South which also blocked news coverage of the civil rights movement). That fall, CBS Films produced “The Gray Ghost,” a syndicated TV series about Confederate Maj. John Singleton Mosby.

“TV is not a leader the way movies can sometimes be,” the historian Brooks says. “It’s a follower of popular culture,” which is set by movies and books. TV decisions at the time were being made by “three white guys on Madison Avenue,” which made it “a very narrow, imitative world, which excluded almost everything.

“If you had shown some of those Manhattanites they could make money by putting on something rural, they’d put on something rural,” Brooks says.

Rhodes is calculating and power-hungry, but he’s also spurred on by the network executives, politicians, and advertisers who profit from his success. He wouldn’t have a show without others' pockets to line.

Griffith as Lonesome Rhodes in the 1957 film "A Face in the Crowd."

While searching for another success like “The Andy Griffith Show,” CBS turned to one of that show’s past writers. Paul Henning won a time slot with a sitcom about a family of Ozarks hillbillies who strike oil and move to Los Angeles. Joining the lineup two years after Griffith, “The Beverly Hillbillies” had none of the subtlety of Sheriff Taylor's banter with Deputy Fife and none of the sweetness of a chat between Opie and his dad. Henning told the press he rejected a network request to put more “heart” into his scripts. His was a slapstick show.

Critics didn't like it.

“If television is America’s vast wasteland, ‘the Hillbillies’ must be Death Valley,” went one often cited review of the show. It didn't matter to viewers. The show was No. 1 in its first season. Its theme song, performed by bluegrass legends Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs, topped the charts, too. The Saturday Evening Post declared that the wasteland was a cornfield.

Some producers were trying to end all the wasteland talk for good. “East Side/West Side” debuted on CBS in 1963 and starred George C. Scott as a New York social worker and, in a rare-for-the-time recurring role for an African-American actor, Cicely Tyson as his secretary. But CBS saw corn as the safer investment. "East Side/West Side" lasted one season, and it gave Henning room in its lineup for another show: “Petticoat Junction,” set between Pixley and Hooterville — the two towns in the Ozarks the Clampetts had left. The next year, Gomer Pyle left Mayberry to join the Marines, and viewers at home could follow his adventures each week on “Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.” Another Henning production, “Green Acres,” went on air in 1965 with the story of a wealthy banker who grew tired of Manhattan life and moved with his glamorous wife to someplace more authentic, located just outside of Hooterville.

At this point, CBS was juggling five comedies about characters in or from two different regions of the South, but it’s doubtful many viewers knew the difference. The necessary broadness required for TV merged the Ozarks and Appalachia into one rustic concept, incorporating all the land in between the mountains into a single “other.”

In Nashville, guitar superstar-qua-RCA record executive Chet Atkins was doing something similar with country music to make it more appealing to a mass audience. Atkins took the drums and electricity of postwar honky tonk and smoothed them out; he dialed back the whine of the steel guitar and turned the fiddles into string sections. Without its previous signature instrumentation, country became more of a feeling than fixed geography. “The Ballad of Jed Clampett” was one of the twangiest, most geographically specific songs on the charts when it hit No. 1.

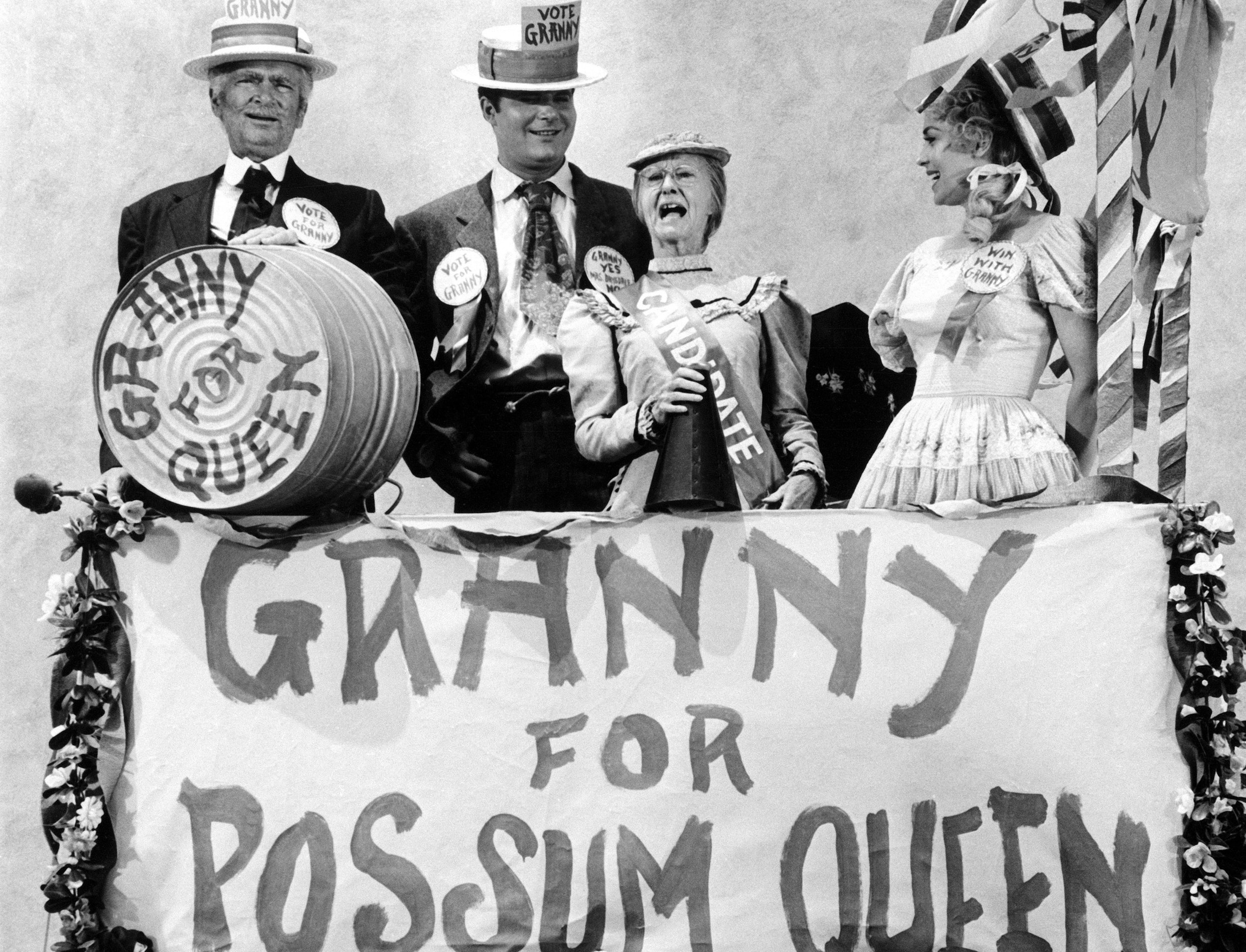

Buddy Ebsen, Max Baer, Irene Ryan, and Donna Douglas, aka Jed, Jethro, Granny, and Elly May

The rural shows did more than obscure regional differences. They also erased the dark side that had long been a part of the hillbilly stereotype.

"[Hillbillies] can be seen as rugged pioneers and stalwart and having a very keen sense of family and closeness to the land and folk wisdom," Harkins says, but "the flip side of that is inbreeding and bestiality and sexual aberrance of various kinds. Rugged stalwart pioneers are sort of drunken and violent and uncontrollable. Closeness to the land is also poverty and backwardness and barefooted-ness and disease.”

There was to be no aberrant sex with the Clampetts. Henning claimed to have studied Ozarks culture, and he rejected the duality of the hillbilly with his shows. "Beverly Hillbillies" executive producer Al Simon told The Saturday Evening Post, “Our hillbillies are wonderful, clean, wholesome people,” then added he wanted the show to redefine the word.

That wasn't all it was redefining. In an episode called "The South Rises Again," Granny becomes convinced that a nearby Civil War film shoot is the real war, which she refuses to accept ever ended. Jed lets it play out. Granny, Jethro, and Elly May drive around Los Angeles waving a Confederate flag. Mister Drysdale, the banker, joins in, calling himself Gen. Milburn Beauregard Nathan Bedford Stonewall Drysdale and preparing to charge into battle before ultimately chickening out. Eventually, Granny shoots the actor playing Grant with a gun loaded full of cookies (it was a family show), and the episode ends with her and the actor drunkenly singing “Dixie” back at the Clampetts’ mansion.

The episode did for the South what TV did for the rural stereotype — it took out the danger but kept a version of the culture. The neo-Confederate makes peace with the Yankee. No one is hurt. Granny gets to hang on to the Lost Cause and the only villain is the citified banker whose actions are driven by greed and cowardice, compared to Granny’s truth and honor. (The lower-class Granny's authentic superiority to the upper-crust, phony Mr. Drysdale sends a message about the perceived inherent value of lower-class whites, too.)

“The shows erase the truth of the Southern states by de-Southernizing it,” Harkins says. “It’s a way of reframing the South as a place of tranquility and peace . . . because it’s all white, because race has been removed from its identity.”

Uncle Jed Clampett, who was shooting at some food when up from the ground came bubbling crude. Oil, that is.

It's unlikely Henning or anyone at CBS read headlines about riots and protests, then believed a bunch of sitcoms about Southerners would speak to the race and class anxieties of middle-class white America. They were just chasing ratings by building on formulas that worked. If they needed to rely on stereotypes, they had to make them easy to digest.

With the twang out of the music and the teeth out of the hillbilly, the media “South” was pure comfort for the right type of person, as the theme to “Petticoat Junction” makes clear.

“Forget about your cares, it is time to relax at the Junction,” goes the song, as a small train chugs along a track, bound for Pixley. The scene cuts to a water tower where three country beauties and their dog are bathing.

“Lots of curves, you bet, and even more when you get . . . to the Junction.”

Lonesome Rhodes has a similar theme song. It’s a country jingle with fiddles and high mountain harmonies, and it would seem like a parody of the “Petticoat Junction” theme, had it not been released years earlier.

Friendly greetin’, Sunday go to meetin’, just plain folks,

Bible-readin’, porkchop-eatin’, just plain folks,

Stew on the table, mule in the stable, drugstore Cokes,

Bill and Mabel, Levi label, just plain folks.

Even if they were strange or a little slow, the people who populated TV's rural landscape were still plain and lovable. And as the ratings showed, they were indeed loved.

Henning was careful with his actors. He advised the cast of “The Beverly Hillbillies” against appearing out-of-character in real life. The media "South" needed to extend to the real world.

By the late ’60s, this started to reverse. Reality was encroaching on TV comedy, mostly through variety shows. Richard Nixon appeared on NBC’s “Laugh-In” in 1968. The Smothers Brothers raised such anti-establishment mischief with their show that CBS asked to see each episode in advance to review for potentially offensive material.

There was still some gold in the hillbillies, though, and CBS wasn’t about to leave it behind. When Andy Griffith left his show, the network kept it running under the new name “Mayberry R.F.D.” Heading into 1969, it was No. 4 in the ratings. “The Beverly Hillbillies” and “Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C” were in the top ten. “Laugh-In” was No. 1.

Looking at these ratings, the writers Frank Peppiatt and John Aylesworth "figured country humor plus musical numbers by that genre's biggest stars ought to be a sure thing," Aylesworth writes in his memoir. He can be forgiven for not remembering the Grand Ole Opry and other barn dance shows that had existed long before, because he admittedly wasn't familiar with country music. He and Peppiatt were Canadian, and while they didn't know country, they did know TV. They'd spent the last decade becoming go-to writers for variety shows, working with everyone from Judy Garland to Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass.

They pitched a variety show set in “a mythical place called Cornfield County," which could be in the South, based on the show's music and accents, or it could be in the Midwest or on the plains, based on the cornfields. Regardless, Cornfield County was in the media “South,” the country of country music under Chet Atkins — the symbolic place where rural, mountain, Southern, and Western were all the same.

With their pitch approved, Peppiatt and Aylesworth hired writers and performers who'd worked on country shows, including a handful of Opry regulars. Country music superstars Buck Owens and Roy Clark signed on to host. And for added realism, the team hired a relatively unknown Georgian named Junior Samples, who had made a couple of novelty records one of the other writers had heard. Samples embodied Henning's rule to stay in character because, by all accounts, he was playing himself. He wasn't Max Baer acting like Jethro Bodine in a rope belt on Rodeo Drive; he was an elementary school dropout who wore overalls and spoke with a deep drawl.

"What you see is what you get,” cast member Lulu Roman told me.

Samples' difficulty reading cue cards became a running joke on the show. When he took dozens of takes to deliver his response to a line about a man having two wives — “That’s not bigamy, that’s trigonometry” — the show kept in his breakups and stumbles.

"Hee Haw" star Junior Samples.

The team had hoped to film at the home of the Opry, then the Ryman Auditorium, but Johnny Cash was shooting a variety show for ABC there, so they booked a CBS news station in Nashville instead.

"The Johnny Cash Show" and "Hee Haw" debuted a few days apart. Cash got good reviews. His show was genuine, somber at times, topical, and willing to leave its genre — Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell appeared in the first episode. “Hee Haw” was the opposite, with its fast cuts between jokes and songs, its mix of puppets and cartoons, its lack of story or context. The show was weapons-grade cornpone, precisely engineered and aimed directly at the top of the charts.

It got some of the worst reviews yet for a CBS country comedy.

“‘Hee Haw’ made its debut last night — and shouldn’t have,” The Boston Globe said. The New York Times called it "a marathon of one-line gags and attempted fast side laughs that Nashville should plow under before next Sunday.” A Nashville paper worried it would “set country back 25 years.” (For its part, "Hee Haw" did book Loretta Lynn and African-American country singer Charley Pride, two strong musical acts, for its debut episode.)

Another piece in The New York Times called "Hee Haw" “the Spiro Agnew of the CBS lineup, the key to the heart of the ‘silent majority,’” a reference to the Americans whom Richard Nixon appealed to — older, white, perhaps resentful of protests and feeling left out by progress.

Surely not everyone who watched and enjoyed "Hee Haw" supported Nixon or the war in Vietnam, but "Hee Haw" had filled a time slot left by the highly topical Smothers Brothers, and the show's lack of politics seemed like a political message.

Just as the rural shows had relied on stereotypes for jokes, critics were now turning to stereotypes to classify the audience. To some viewers, Junior Samples may have been just like a dopey cousin or a neighbor they avoided. To others, he was everyone from the South — overweight and undereducated, the type of guy wooed by Nixon's Southern strategy.

"Traits that were seen positively among many Southerners carried potentially negative connotations among outsiders," Sara K. Eskridge writes in the journal Southern Cultures.

“That’s where you start getting, in my mind, this consistent connection with rurality as right-wing,” says Victoria E. Johnson, author of “Heartland TV: Prime Time Television and the Struggle for U.S. Identity.”

As the first season of "Hee Haw" ended, it wasn't clear who was laughing with the cast and who was laughing at them. But either way, people were laughing.

CBS renewed “Hee Haw” for two more seasons.

In his 1971 track "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised," Gil-Scott Heron announces that “Green Acres, The Beverly Hillbillies, and Hooterville Junction will no longer be so goddamn relevant.” He says the theme song of the revolution will not be sung by Johnny Cash or country singer-turned-CBS variety host Glen Campbell.

Aylesworth writes in his book that around this time, CBS executives gave him and Peppiatt chilly, awkward reactions during meetings. He suspects they were upset that a show as base as "Hee Haw" was doing so well, even if it was a natural outgrowth of the network's comedy lineup.

Maybe the criticism had rattled CBS. Maybe they got the message that stereotypes and fantasy were not what the nation needed, and a return to its “Tiffany Network” image was due.

Maybe not.

“I don’t think CBS cared a whit about whether they were square or not,” Brooks, the former executive and TV historian, says. “They cared about the money coming in. It’s a numbers game."

By the early 1970s, the way TV viewers were measured had become more sophisticated. Instead of focusing on the total number of people watching a show, the ratings services began to look at who was watching.

“That started to expose the types of audiences the westerns and the rural sitcoms were really getting," Brooks says. "Even though the big gross audience was large, when you look behind the curtain, they’re mostly old and mostly rural."

And the mostly old and mostly rural audience wasn't who advertisers wanted. The shows had to go.

On the porch in Mayberry.

If fans of the canceled shows were part of the silent majority who felt like their way of life was falling away from them, like they were condescended to by the coasts, and if they worried they were powerless against the rich and the elite, then the Rural Purge confirmed those feelings. By choosing shows with better ad potential, CBS was telling the rural audience it wasn’t worth as much as younger, more urban viewers. And it was doing it on the most powerful communications medium available.

This was business for CBS; for those it was rejecting, it was personal.

“Television’s omnipresence in our homes, in our lives, it’s everyday-ness confers upon it a sense of realness and authenticity to us. It speaks to us, literally, where we live," the historian Johnson says. “If you’re a regular viewer of a series that lasts 10 years, that’s a weekly relationship with people who you feel you get to know better than some of your own family members. It’s a sustained engagement that implies a kind of intimacy and veracity.”

CBS’s post-Purge programs embraced a different kind of veracity. They took time to gain viewers, and once they did, they generated more than just ad dollars and positive reviews. They pushed further into what Brooks calls TV’s “Relevance Era,” with news, teleplays, and sitcoms reflecting what was going on in the outside world. "M*A*S*H" was set in a war zone. And from the fall of 1971 to 1975, at least one top-five show was led or hosted by a black actor. TV wasn't as forward-looking as cinema or literature, but it was moving into the future.

The past wasn't over yet, though.

At the end of “A Face in the Crowd,” a hot mic catches Lonesome Rhodes saying what he thinks of his audience. They turn away from him. Later, at his apartment, one of his former writers predicts what will happen next:

"You're gonna be back in television. Only it won't be quite the same as it was before. There'll be a reasonable cooling-off period, and then somebody will say: 'Why don't we try him again in an inexpensive format? People's memories aren't too long.' And you know, in a way, he'll be right. Some of the people will forget, and some of them won't. Oh, you'll have a show. Maybe not the best hour or, you know, top 10. Maybe not even in the top 35. But you'll have a show. It just won't be quite the same as it was before. Then a couple of new fellas will come along. And pretty soon, a lot of your fans will be flocking around them."

"Hee Haw" was back on the air with new episodes eight months after it ended, this time as an independently produced show made available directly to local stations through syndication. With this business model, the show could speak more directly to the rural viewers CBS had turned away from, since local stations decided whether and when to air the show. As seasons passed, “Hee Haw” started to seem more like a tribute than a parody. The producers put more songs between skits. They added a hymn to each episode. With no other shows regularly featuring country music, "Hee Haw" became part of the genre's culture. It ran for 22 more years.

Buck Owens and Roy Clark, pickin' and grinnin'.

In those years, the South changed. In spite of the continued problems of racism and class inequality, the region attracted auto manufacturers and other big businesses. It suburbanized. This new wealth among white Southerners, combined with the proliferation of cable, meant the old days of needing a mass audience to sustain a program were over.

"Hee Haw" lasted in this new economy until 1993. That year, Jeff Foxworthy went triple platinum with his comedy album, "You Might Be A Redneck If…" The comedy plays to a crowd that still finds itself left out of the mainstream, despite whatever financial or political success they have. It was built for the new suburban South. Foxworthy was a star for a fractured media and a fractured country. After his Blue-Collar Comedy Tour launched, Foxworthy said the tour's inspiration — the popular tour of black comedians and Spike Lee-directed film "The Original Kings of Comedy" — was for people who were "hip," and his tour was for people who were "not hip."

"They're the ones who wake up every morning and go to work and go to war, and, dadgum, there's a whole lot of 'em out there," he said. It's reminiscent of Lonesome Rhodes describing his audience of as "everybody that's got to jump when somebody else blows the whistle."

The hillbilly stereotype settled into corners of cable and syndication, but it didn’t stay there long. In the 2000s, after a recession, wars, and the election of the nation's first black president, cable networks turned to "moonshiners, noodlers — men in the wilderness being men, challenging the niceties of modern life," as Harkins describes them. These new reality stars held up the old stereotypes. There was the buffoonery of "Here Comes Honey Boo Boo," the rugged paternalism of "Duck Dynasty," and the tight-knit morals of the Duggars and their 19 children.

With reality TV, the stars are always in character, amplified for the medium and living in the real world. It’s not real at all, though: Reality television is about as real as Larry the Cable Guy’s collar is blue, but because it’s presented as documentary, these caricatures walk among us. And when the men of "Duck Dynasty" use Christian values as an excuse for homophobia, it doesn't matter whether they're pandering to potential viewers or actively expressing their politics. The characters are the men.

“Lonesome Rhodes is the people. The people is Lonesome Rhodes.”

"Duck Dynasty" may have ended in 2017, but the idealized, televised old America will always be as inescapable as it is unreachable.

The Robertson family of "Duck Dynasty"

If money can be made from a rural audience, it will be. In some of its services, the Nielsen ratings agency classifies city audiences with terms like “Urban Achievers” and “Money & Brains.” The rural audience gets categories like “God’s Country,” “Mayberry-ville,” and “Shotguns & Pickups.” The television schedule is made up of red and blue blocks; each time slot is a battle in the culture war. The coding can be subtle or explicit. There's "Truck Night in America" or "RuPaul's Drag Race," Fox News or MSNBC. Even "Petticoat Junction," "The Beverly Hillbillies" and "Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C." are back on the rerun-heavy MeTV network, which also broadcasts "All in the Family."

The past five decades have erased some of the differences. "All in the Family" and the hillbilly shows have more in common than it seemed when they were new. Both rely on laughing at someone who is backward in their thoughts or ways of living, someone who shouldn’t really exist in our modern world. "All in the Family" had a message while the other shows had none, but it's not clear how many people got it and how many actually agreed with Archie Bunker's views. Now, the sets of each are museum pieces: Archie's armchair is in the Smithsonian, and the cornfield set from "Hee Haw" is in the Country Music Hall of Fame.

On MeTV, all the shows run together. There’s nostalgia for an America that never existed and satire that pushes for an America that could be. But they're both covered up by another layer of nostalgia, a longing for a less divided time, for a country where this was the most consequential difference you could find on TV.