Southerners profess great love for homegrown tomatoes. Only a few of us will do the sweating and digging ourselves. So while tomatoes have been part of Southern culture from the beginning, our hunger for them means too many people in the fields don’t get treated fairly.

Story by Shane Mitchell | Photographs by Fernando Decillis

My cousin Edward Mitchell Seabrook Jr. was a shy man with two passions.

The first was science fiction. He would read it in his office on Broad Street in Charleston, South Carolina, where he ostensibly sold real estate and insurance. The pulp-novel overflow crowded the bookshelves in the second-floor bedroom I shared with one of my sisters during a grossly hot summer vacation at Edward's beach house on Folly Island. Edward’s mother was sister to my Nana, his father cousin to my grandfather. (Our family’s bloodlines are tangled; don’t anyone crack Deliverance jokes.) As a teenager, lying next to a box fan with a damp washrag on my forehead, I devoured paperbacks with lurid cover art by Roy G. Krenkel and Frank Frazetta: Tanar of Pellucidar, Pirates of Venus, The Cave Girl.

His other passion was tomatoes.

Because Edward’s front yard on the Folly River was a sandy coastal mess of prickly crabgrass and Spartina, he positioned 50-gallon industrial drums, sawed in half, outside the kitchen door. He basically grew tomatoes in tin cans but was a member of the Agricultural Society of South Carolina. His seedlings raced up poles in a mysterious soil mix about which he was tight-lipped. As the sun burned off dew and the hour for lunch approached, Edward lumbered down the rows checking ripeness until he found a few about to crack with juice, and twisted the warm fruit from its vine. The smell of tomato leaves fell somewhere on the spectrum between scorched tobacco and a mechanic's grease rag. The flavor of the tomatoes themselves, an excruciating alchemy of acidity and sugar, only he knew how to achieve. In the kitchen, one of my great-aunts or Edward's wife, Lucy, made sandwiches. I can’t recall if the mayonnaise was Duke’s, but the bread was squishy and white. I ate mine, bare feet dangling at the end of the dock, or in a rope hammock on the porch, with one of Edward’s fantasies about mutant aliens inches from my nose.

Where would Southern culture be without the tomato?

One of the earliest references in American cookery appears in the private journals of Harriott Pinckney Horry of Hampton Plantation. By 1770, she was collecting receipts in a journal that became an invaluable household document about colonial life in the Santee Delta of South Carolina, especially during the Revolution, when she managed the property. Her house served as a refuge for women and children fleeing the British occupation, and it was in her fields where Brigadier General Francis Marion, known as the Swamp Fox, hid when enemy troops arrived at her door to search for him. Horry’s instructions “To Keep Tomatoos [sic] for Winter use” by stewing and storing in pint pots with melted butter as a sealant seems labor intensive to those of us equipped with modern refrigeration and access to hothouse varieties at the nearest Publix. Not only was it a hedge against a season of want, but also a pragmatic embrace of what the New World offered.

Since that early recipe, the tomato’s appeal for Southerners has become universal. Tomato aspic at church suppers. Tomato pie for picnics. Tomato gravy with cat-head biscuits. Tomatoes in succotash, chutney, puddings, and perloo. Fried green tomatoes did not originate in the South, but we do them best and can thank novelist Fannie Flagg for indelibly mythologizing those golden-crusted disks in Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Café. One of the first soul-food versions appears in Helen Mendes’ The African Heritage Cookbook (1971).

But no one in the culinary canon of the South has ever rivaled Ernest Matthew Mickler. In his seminal White Trash Cooking, he wrote this about the Kitchen Sink Tomato Sandwich:

In the peak of the tomato season, chill 1 very large or 2 medium tomatoes that have been vine-ripened and have a good acidy bite to their taste. Take two slices of bread. Coat them with ¼ inch of good mayonnaise. On one piece of bread, slice the tomato ¼ inch thick. Salt and pepper that layer. Add another layer of sliced tomato, and again salt and pepper. Place the other piece of bread on top of this, roll up your sleeves, and commence to eat over the kitchen sink while the juice runs down your elbows.

Finding my way back to that sandwich took up most of my year.

“Que es el trabajo?” asked Julia Perkins. “What’s the job?”

A group of women facing her at the bulletin board repeated the English lesson in unison. On a Sunday afternoon in late April at the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) headquarters, female members gathered for their weekly coffee klatch to learn a few handy phrases, trade daycare schedules, and discuss the cost of groceries. Boxes of Polvorones and Canelitas cookies laid scattered on the folding table. A banda tune by Los Jefes de la Sierra Grande leaked from the sound booth of Radio Conciencia La Tuya next door. Murals depicting tomato workers in the field covered butter yellow walls. Hand-painted slogans “No Mas Abusos,” “Comida Justa” and “Justice for Farmworkers” hung above a cluster of desks.

“What kind of work is it?” said Perkins. “What do I need to apply?”

Perkins, a CIW education coordinator born in North Carolina, ended her lesson, and the women rose to rearrange the folding chairs and put away the snacks. All dressed neatly in jeans, cotton tops, clean sneakers. Gold necklaces, pierced ears. Long hair pulled back in sensible ponytails or braids. Cell phones tucked back into purses. Many still worked in the fields; others were field agents for the Coalition. Nice ladies, all.

Bet you’d never guess they’re expert hunger strikers.

Immokalee (pronounced Im-MOCK-a-lee) is ground zero for Florida’s commercial tomato crop. Broad, flat fields line the main road into town from the Gulf Coast, and on certain stretches, high chain-link fences prevent panthers from crossing the asphalt that cuts across their swampy Western Everglades habitat. Loaded tractor-trailers rumble out of packinghouses. A pinhooker market in an open lot sells produce too ripe for long-distance shipping. A party store advertises piñatas, and bottles of Mexican Coca-Cola fill the cold drink case at Mr. Taco. Waitresses in bustiers and fishnet stockings circle gamblers hunched over slots at the Seminole casino. Street roosters wage turf wars in grassy ditches. Blue tarps still patch damaged roofs long after Hurricane Irma pummeled Florida last year. In an improvised courtyard between ramshackle mobile homes with boarded-up windows, little girls build sand castles in the dirt pretending it’s the beach. One of their parents, who pays $60 a week to share the single-wide with up to 11 other occupants, mentioned that after the 2016 election, a few babies were named Melania.

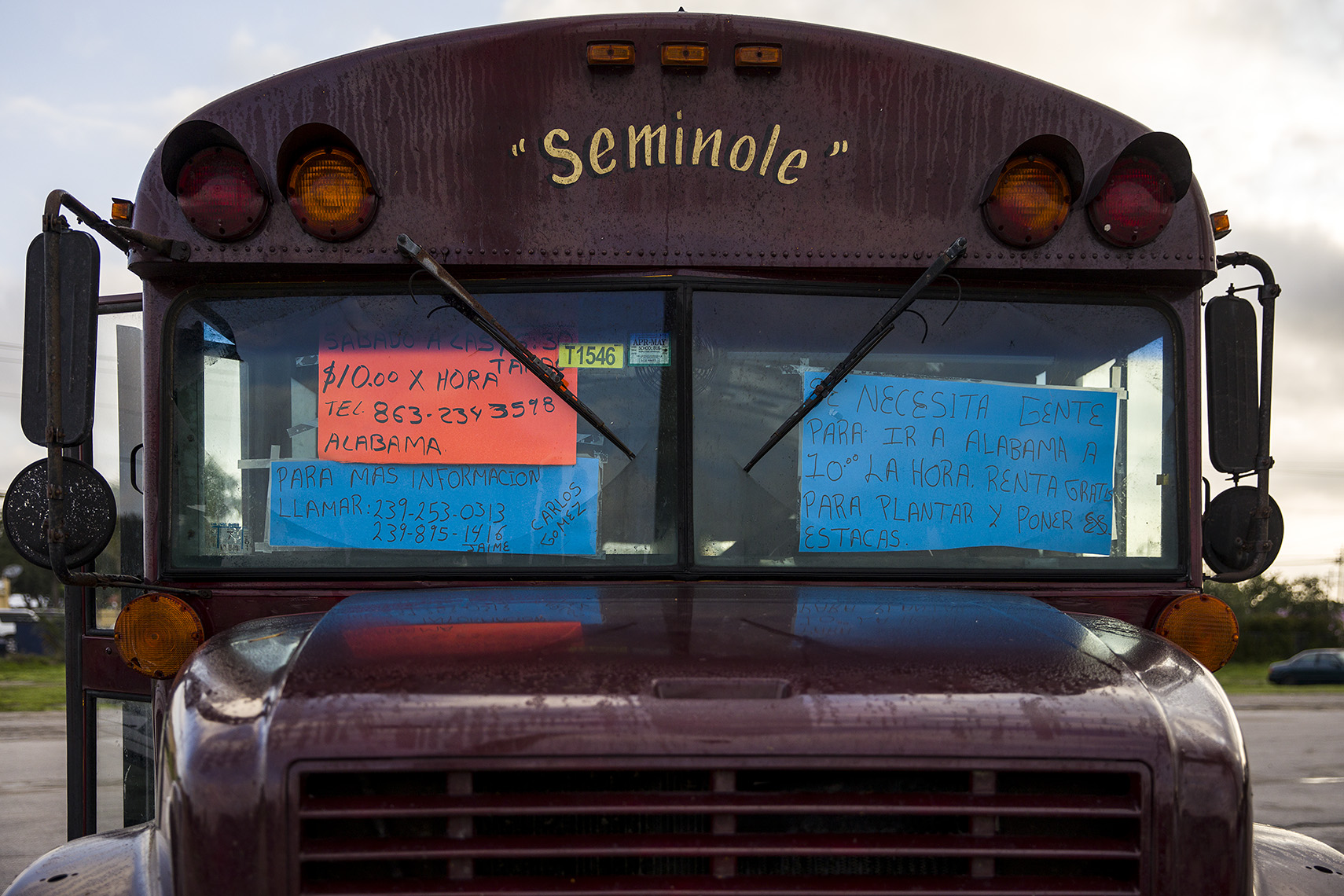

Across the street from CIW headquarters, the parking lot at La Fiesta #3 grocery store serves as a depot for the battered school buses that transport agricultural workers. The workers buy warm tortillas inside at crack of dawn each morning. When the buses return at end of day, water coolers are dumped on the asphalt to evaporate in the still torrid heat. Many town residents commute on bicycles, not due to a quaint civic ordinance but because they can’t obtain a legal driver’s license or afford car payments on a harvester’s wage. In 1960, Edward R. Murrow reported from Immokalee on the harsh lives of African-American migrant workers in the CBS documentary Harvest of Shame; now, the town’s population has largely shifted to Latino and Haitian. Whatever change has taken place in the fields since — as basic as access to shade and water, as critical as exposing wage theft and sexual harassment — is in great part due to Coalition activists.

Members of the CIW are fantastic at nonviolent resistance. One of their cornerstone initiatives is the Fair Food Program, a humane workplace monitoring collaboration with big ag companies including Gargiulo, Pacific Tomato, and Lipman Family Farms, and fast food giants McDonald’s, Subway, Chipotle, and Taco Bell. Walk through the produce aisle at Whole Foods or Trader Joe’s and inspect the tiny green Fair Food seal on those packets of glossy grape tomatoes and genetically engineered slicers. It represents decades of toil and deprivation.

But the Fair Food seal can’t be found at Publix or Wendy’s.

Not yet.

The next day, Nely Rodriguez, a robust woman in her mid-50s, walked into the CIW offices and shook my hand. She wore a caramel-colored knit sweater over a tank top and capris. Rodriguez, originally from Tamaulipas, Mexico, spoke in a low alto.

“When I first came here, I picked apples and asparagus in Michigan,” she said. “Then in Florida, tomatoes, squash, and eggplant; and since 2007, my work at the Coalition is organizing in the community, with the Sunday women’s group, the radio, and labor-abuse investigations outside the Fair Food Program.”

She also takes part in hunger strikes. Her first fast was in 2012 — a weeklong protest at Publix headquarters in Lakeland, Florida. Founded in 1930 by George R. Jenkins, Publix is the largest closely held regional supermarket chain in the South, with 1,191 stores and gross revenues of $34 billion, so if you shop for groceries anywhere between Alabama and Virginia, chances are good you’ve bought tomatoes at a Publix, or Publix Sabor, themed stores catering to Hispanic Americans. The company’s official position for not taking part in the Fair Food Program maintains the CIW campaign is a labor dispute between workers and suppliers, rather than a human-rights issue. More recently, Rodriguez traveled up to New York in late winter for a chilly “Freedom Fast” strike outside the Park Avenue offices of Wendy’s billionaire board chairman Nelson Peltz.

We sat at a picnic table under a pergola behind the cinder-block building. Doves cooed on a tin rooftop. Breezes rustled the sabal palms.

“I’ve never fasted. How did you feel at the end?” I asked.

“To be honest, I thought it would be more difficult than it was,” she said. “For the first or second day, I had headaches, was tired, but by the third day, I felt more full of energy, lighter, and wasn’t hungry anymore. Taking on a fast like this, you know you’re doing it for a just cause, and you've seen abuses in the community and you want them to stop.”

“Was there a time in your past when you were hungry?” I asked.

“Sometimes, working in the fields back in Mexico, because you had to finish a job and you can’t stop, you get hungry. But for days and days because food wasn’t available, like the Freedom Fast? No. There were days when food was just tortillas and beans, but there always was something to eat.”

“So the strike was a different kind of hunger?”

“During the fast, I found myself reflecting on the things I’ve seen, like the mothers here who have to get up extremely early to drop their kids off at daycare or school, but under the Fair Food Program, that is no longer the case. If we can make this Program expand, those things will change. Those things come into your mind and you can power through. After five or six days you want to continue. The feedback you get, the support from the community, that encouragement helps you get through the more difficult parts, urges you on.”

“What was the first thing you ate after?”

“To break the fast, we ate bread all together. Then, we celebrated at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine. The bishop was there, they had mariachis, and an enormous spread. I served myself salad, rice with vegetables, butternut squash soup. And at the end tres leches cake with whipped cream on top. That tasted so good.”

Rodriguez smiled.

“That tasted so good.”

Angela Navarette bought the maroon lace curtains shading windows of a modest tan ranch in a subdivision known as Farm Workers Village — company housing owned by Lipman Family Farms, one of North America’s largest field-tomato growers, beyond Immokalee town center where sidewalks end.

“They make it look nice. More like home,” she said.

Her husband, Ignacio Lopez, rested in an armchair, a straw cowboy hat tipped back on his head. The room was stuffy in late afternoon. Julia Perkins and I sat at the dining table covered with a floral-pattern vinyl cloth while her colleague, Gerardo Reyes, examined the faulty settings on the air conditioning unit. On the stove, a pot of pollo con mole bubbled. Lopez, 76, grew up in Veracruz; Navarette, 61, was born in Guerrero. Both were members of the Coalition. They met in Immokalee; each had children from other marriages living on both sides of the border. She got here first, to harvest lettuce in Belle Glade and corn in Indiana. A coyote dropped him off in Tennessee. They share the house in Immokalee with six more workers during the winter growing season, then follow the crop in summer to South Carolina and Virginia.

“We came because of necessity,” Navarette said, her face darkening. “In Mexico, I was taking care of all the kids of my daughters and sons. One was studying to become a nurse, and so I tried to think of ways to support her, and coming here became an idea.”

I asked Angela her full name.

“Hernandez-Navarette,” she said. “But not the bad Navarettes. When I first got here, people at the company looked at me funny when I said my name, then I learned the story, but it still took a while to clear it up.”

She referred to a notorious family of crew bosses that brutalized and enslaved 12 Latino tomato pickers, holding them captive and chained inside a box truck for almost 2½ years.

Navarette got up to stir the mole.

“Is there a special technique to working tomatoes?” I asked.

“It took me a month to learn,” she said. “The crew leader told me it’s really heavy work, and I felt uncomfortable taking a break all the time because everyone was looking at me, but Ignacio works really quickly, picking up the slack. He’s a matador.”

Reyes explained matado is slang for killer or badass, the fastest one who makes everyone else look bad.

“Even with my age, I love working in the fields,” said Lopez. “I’m fast, they don’t beat me. When I get tired, I am limping, my feet hurt, but I’m still out there. I’m fresh like lettuce.”

“Do you concentrate on a tomato variety?”

“We pick tintos,” said Lopez. “It’s a little bit easier than picking greens, because with the greens, everyone moves so quickly, but with these, it’s easier to spot because they’re a little red.”

A bucket of tintos sat on the kitchen floor, next to a five-gallon pickle tub and six-packs of Grape Crush. Navarette brought one to the table. It was about as ripe as a snow globe.

“How many buckets a day?” I asked.

“Around 75,” said Lopez. “Sometimes only 25 or 30 when there’s not many left, but the piece rate for the reds is higher."

Each full bucket, or “piece,” weighs 32 pounds. On a great day, that adds up to 2,400 pounds hauled by hand to a field truck by a bow-legged septuagenarian shorter than me.

Reyes, passing around a plate of microwaved tortillas, remarked that harvesting the tinto used to be a niche market of pinteros, or pinhookers, who hired day labor not affiliated with an established crew and paid them cash under the table.

Navarette served her pollo con mole next to generous scoops of rice mixed with dried green pigeon peas and stewed tintos. (She doesn’t eat raw tomatoes.) Her sauce covering the chicken legs was nutty, mildly fiery, and had an elusive sweetness — indigenous Nahuatl speakers called it mōlli or chilmōlli. I wanted to bathe in it.

“If we see you in South Carolina, I will teach you how to make this,” she said.

We get the word “tomato” from the Nahuatl language. The root word tomatl was adapted to tomate by the Spanish, and then the “e” distorted to “o” for English speakers. That subtle shift from consonant to vowel is a history of conquest, colonialism, and migration. Nahuatl is the Aztec language spoken in central Mexico (including the Navarette-Lopezes' home states of Guerrero and Veracruz) and was considered the prestige language of pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica. The wild ancestor of all tomatoes is Solanum pimpinellifolium, a resilient perennial with pea-sized fruit originating in northern Peru and southern Ecuador, with cultivar cousins appearing in climates as varied as the Atacama Desert and on the lower slopes of the Andes. The modern tomato, Solanum lycopersicum, took another 10,000 years to evolve, and while the date of domestication is unknown, it was apparently being cultivated by Aztecs around 500 BC. The tomato then dispersed on Spanish trade routes to Europe and Asia, Africa and the Caribbean, but unlike other New World botanical discoveries such as peanuts or corn it was greeted with far deeper prejudice because it belongs to the Solanacaea or poisonous nightshade family.

The earliest account of tomatoes grown in North America is found in herbalist William Salmon’s Botanologia (1710), although Spanish settlers likely introduced the plant to their colonies and missions on the southeast coast centuries earlier. Seeds may also have arrived through the Jamaica slave trade. In Louisiana, emerging Cajun and Creole culinary traditions adopted the tomato for its gumbos and jambalayas. Elsewhere, bias continued into the 19th century. In 1836, S.D. Wilcox, editor of the Florida Agriculturalist, wrote after eating his first: “The tomato is an arrogant humbug and deserves forthwith to be consigned to the tomb of the Capulets.” At the end of the century, the father of the modern commercial tomato, seedsman Alexander W. Livingston, achieved the varieties he named “Paragon” and “Acme” through generations of selective breeding. One hundred years more, too much hybridization — for shape, durability, color, disease, and drought resistance — had a singular unintended consequence. Tomatoes started tasting downright boring.

And that brings us to the flavorless globe, picked by migrant workers and reddened by ethylene gas in packinghouses before landing in supermarkets with callous public relations positions on labor practices.

I wouldn’t grace that between two slices of bread.

Angela and Ignacio left in the night.

“Let’s take the golf cart,” said Richard “Bubba” Crosby.

On a cloudless morning in late June, he climbed aboard a sky blue Ford 3000 tractor and set out for his three-acre vegetable patch, a few hundred feet off the back porch of his house in Hardeeville, South Carolina. A tall man with thinning white hair and gnarled hands, the 91-year-old retired tomato farmer descends from Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and is a distant cousin to Harriott Pinckney Horry, too. At one time, Crosby farmed 300 acres in rented fields strung on the Carolina Lowcountry coast between Hilton Head and Beaufort, before bridges connected the barrier islands on Port Royal Sound.

“I started farming when I got out the Army in ’47,” he said in a gravelly drawl. “I used my daddy’s tractor and planted watermelons. We had to use a horse to side it up close, to work the crop itself, because tractors weren’t too good then.”

He also grew cotton, daffodils, rice, corn, soy, and velvet beans. Raised beef cattle. By the 1960s, he shifted into tomatoes, and for a year contracted to grow for the same company that currently employs Angela Navarette and Ignacio Lopez. That arrangement didn’t work out.

“I learned how from nothing, started growing tomatoes because they was growing in Beaufort,” Crosby said, shutting off the vintage 1965 tractor inside the electric deer fence. “Planted 20 acres the first time.”

His property wraps around a bend of the New River, not far north of Savannah on Oaktie Highway, between alligators in the marsh and rattlesnakes in the piney woods. Crosby and I strolled down three neat rows of staked vines, about 100 feet long, heavy with fruit.

He bent down and moved leaves aside with his walking cane.

“You want to know how we plant those tomatoes to make ’em? Is that important? I fixed the ground like a month before time to plant, put a plow down about that deep right where the row is going, and it brings some clay up a little bit, softens the dirt, and I put fertilizer, 5-10-15 heavy potash, the length of those rows, a ten-quart bucket, there, one time. I put bagged lime down like the fertilizer, because the garden gets blossom-end rot, then wait a couple of weeks before planting the crop. They susceptible to everything, you know.”

“What kind of tomatoes?” I asked.

He chuckled.

“The tomatoes that I plant, they come with a number on them, I get a few from a friend of mine who is in charge of the planting operation at 6Ls.”

“So you’re planting the same kind as Lipman?”

“They owe me plenty.”

Southern farmers like Crosby can no longer compete against agricultural conglomerates with million-dollar tractors, acreage in multiple states, proprietary cultivars, and experimental field-trial stations. Independent packinghouses, which once serviced smaller growers, have also shuttered or merged.

We left the tractor in the field and returned to his cement porch, where he showed me a flat of scrawny seedlings reserved for fall. Red orbs, stem side down, ripened on a picnic table. Crosby settled himself in a rocking chair as his wife Joyce, 86, came outside to offer bottles of cold water. They have been married for 64 years. A petite woman with downy hair, she still preserves broccoli, cabbage, collards, and corn from their garden, and had just finished canning 60 quarts of snap beans. We sat, rocking, to catch the breeze and recover from the direct sun.

“We old but we good,” she said, smiling at her husband.

A mosquito hawk droned the porch.

“How many tomatoes do you get in a season?” I asked.

“We picked nine gallon buckets so far, but I’ve given away a bunch, and sell enough off the table to pay for the garden.”

Joyce chimed in.

“Bubba just gave up Farm Bureau. He was on the school board, done a lot of community stuff, played softball until he was 79.”

“When we got married in ’54, there was local blacks around here didn’t have any work,” she said. “And they all worked in his fields. We had a boy that started as a teenager, he was an alcoholic, and I fed him a big plate of dinner, ate everything we did.”

“There was no welfare then,” said Crosby. “Nobody had anything.”

“How many workers on the farm?”

“I had two, sometimes three,” he said.

“And when picking?”

“Two, three hundred.”

“And where did all the pickers come from?”

“They were transit, same as they got in Beaufort now. We had a labor camp. When the season was over they’d go up the road.”

The Crosbys' youngest daughter, Cheryl, pulled into the yard. A horse trainer and wild animal rehabber, she had a baby raccoon in a meshed pet carrier. She used to pick tomatoes for fun as a child and sold them out of the field.

“If we picked a bucket of tomatoes, that was our money. I’d spend it on junk food at the Nickel Pump gas station,” said Cheryl, as the raccoon crawled into her arms and perched on her neck. “We’d go to the movies. He didn’t pay us, but we went to private school.”

She confessed a dislike for raw tomatoes.

“But I like salsa and ketchup and tomato sauce,” she said, selecting unripe slicers from the table. “I’m getting these for someone who wants to make fried green tomatoes. Fresh out of the garden taste, it’s a lot sweeter.”

“Bubba, what’s the best way to eat them?” I asked.

Crosby laughed.

“I eat them a little bit green. It don’t have quite as much juice running down your arm.”

“But what about a tomato sandwich?”

“I use Miracle Whip,” said Joyce. “My mother used Hellmann’s. You have to do what you want with the mayonnaise, and I peel the tomato and slice it regular. Salt, pepper would be good. We buy that Nature’s Butter Bread. That's what he likes.”

“Ugh,” said Cheryl.

“The migrants are here.”

I heard that at gas stations and convenience stores along Highway 21, when at the height of tomato picking season in South Carolina, the population balloons on Port Royal Sound. (In the late 16th century, the settlement of Santa Elena, on Parris Island, was capital for the entire Spanish colony of La Florida.) As in Immokalee, trucks hauled loads to packinghouses on the main road. Low-profile bodegas offered check cashing and international call services. Scarecrows in white hazmat suits and bilingual trespassing signs were posted at the entrance to the fields, intentionally shielded from view by high scrub. Outside the antebellum port town of Beaufort and the Marine Corps Recruit Depot, this region also remains rural. Here, the predominant culture is Gullah, with the community of Frogmore on Saint Helena Island a place of historic significance for African Americans; all it takes is a turn onto Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive to pass by the Penn School, where emancipated slaves first received a formal education in 1862 on a campus of whitewashed clapboard buildings.

Early on the morning of the summer solstice, the forecast for Saint Helena included a heat-index warning of 110 degrees. It remained cool enough under the shade trees as buses dropped off pickers at a labor camp belonging to one of the major tomato conglomerates. Laundry dried on lines outside one of the row houses, portable toilets sat under a carport shed, flatbed trucks stacked with empty dumper bins parked in the yard. The pickers headed first to a hand-washing station, and then jostled for seats at picnic tables. Most of them young men, wearing baseball caps, back braces, bandannas, work boots, cut off stretchable sleeves to protect forearms, their jeans stained muddy green on the knees. A few women scattered among the crews.

Crew bosses and ag company representatives also arrived.

“Hola muchachos,” said Gerardo Reyes.

The response was muted, polite.

The Coalition of Immokalee Workers conducts field sessions at farms that have signed the Fair Food Program agreement, and during the season they travel north along the same route as the migrants. Saint Helena is a regular stop. The session addresses rights and responsibilities of both workers and farmers: standard safety practices, tracking hours, and how to report discrimination or abuse. It takes about an hour. That morning, the CIW activists worked through three sessions, with about 200 workers in all. As Reyes talked, Julia Perkins and Nely Rodriguez handed out brochures. Other staff held up murals painted on plastic tarps to illustrate key points. One had an outsize cartoon sun burning above a row of vines, and Reyes commented that on really hot days, all you see is that big yellow orb. The crews laughed.

The mood shifted when Nely Rodriguez took her turn to talk about sexual harassment, standing next to a mural of two workers commenting on a female picker’s appearance as she bent over in a field. Some men snickered, looking nervously at each other for support.

“What if this was your mother or sister?” she asked.

That same morning, Melania Trump left the White House for Andrews Air Force Base, en route to an unannounced humanitarian visit with detained immigrant children and unaccompanied minors at a shelter in a Texas border town. She wore a $39 olive green Zara jacket with the words “I REALLY DON'T CARE, DO U?” printed in faux graffiti on the back.

Neither do many tomato producers. According to Farmworker Justice, a non-profit advocacy group in Washington, D.C. that addresses immigration policy for migrant and seasonal workers, more than half of America’s two million farmworkers are undocumented and marginalized. And despite the CIW’s outreach, this still engenders an environment where unscrupulous employers, from crew bosses in the field on up to white collars in corporate offices, need to be held accountable for illegal or deficient practices to get their crops to market.

When tomato pickers migrate with the crop, their crew bosses send a truck ahead to transport bare necessities. Personal microwaves and wall-unit air conditioners. Chairs. Storage tubs filled with clothing, linens, pots and pans. Angela Navarette packs chilies because she can’t find the right variety for her mole in South Carolina. For the season in the Lowcountry, she and Ignacio Lopez were assigned to a rented house with seven other workers, a prefab double-wide set back from the road leading toward Land’s End on Saint Helena. Cots for the bachelors crammed the living room, but the kitchen made Navarette happy as she preferred it to more basic quarters in the labor camps.

We stood at the sink as she cut up two chickens. She fried plantains in a pan. Then garlic and onion, peanuts, raw pumpkin seeds, raisins, and sesame. Ground together cloves, cumin, cinnamon. She chopped two large field tomatoes in a blender with toasted chiles and broth from the stewing chickens.

“My secret ingredient,” she said, her dark eyes brightening. “I thought this one up myself. Galleta de animalito.”

Animal crackers.

Certainly not traditional for mole, but the smashed cookies made the sauce intensely personal.

She stopped stirring the pot to check laundry soaking in a bucket outside on a porch next to a dead refrigerator. It’s an all-day job to get tomato stains out of her clothes.

“Old house, old bath, old clothes. But it’s all going to be clean.”

“What do you wear?” I asked.

“A long-sleeve blouse, shirt over that. Some people use lots of bandanas, but I put one under my baseball cap. Any other hat gets in the way of the bucket. In Mexico, all the campesinos would use a sombrero.”

Cicadas buzzed in the woods.

“When you’re picking tomatoes, your hands get stained and dirty,” said Navarette.

“How do you get it off?”

“You take a tomato and break it open and rub on like soap, and then the stain comes out when you wash your hands.”

The chicken took three hours to cook down, and despite air conditioning on full blast, the kitchen grew uncomfortably steamy. I asked Navarette how she abided in the summer weather. She dug around in the refrigerator and pulled out a liter bottle of pineapple flavored Suero Oral electrolyte solution. (Suero means serum in Spanish.) The caution label recommended use for severe dehydration caused by diarrhea, vomiting, or excessive perspiration.

“Nobody trusts the water on the truck. Who knows where it comes from? I drink this instead.”

Lopez parked a pickup in the yard and came inside. He sat down and pulled up his pant legs to show me his knees, the joints swollen, inflamed, possibly arthritic. He kept rubbing them. Lopez explained he’d been to a free clinic for medicine and X-rays, but the doctors thought he might need an operation. Two months before, when I met him in Florida, he was still in the fields. Now, he cleaned crew quarters.

A matado no longer.

“Not a lot of tomatoes right now,” he said. “It’s not a good year. The cold impacted the crop here, and the rain, too. We used to get checks of $400 a week. There have been seasons when Angela was paid $1,000 in a single check. But now, every week we’ve been here, it’s about $140.”

“How do you live on that amount? How can you afford groceries?”

They looked at each other.

“We are worried about what will come next.”

“After 18 years, I’m tired,” said Navarette, her lined face sadder. “I want to go home. Ignacio wants to go back to Veracruz, but I would like to be in Guerrero again.”

“We are living in a country that’s not ours,” said Lopez. “We struggle with that. We think about how one day to the next everything could change, and how many people have been taken away. You have to be resilient. We need to not let our passions get the best of us. Just endure.”

Earlier that same week, while dining at a Mexican restaurant in Washington, D.C., Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen was heckled by protestors shouting “shame” for her role enforcing the administration’s zero-tolerance immigration policy and the separation of children from their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Navarette served lunch, the mole even better than last time.

“If we see you in Virginia, I will teach you tamales,” she said.

The next day, Howard Chaplin pumped gas opposite me at the Sunoco on Sea Island Parkway. A slim man with wire-rim glasses and curly white sideburns, he politely wished me a good morning in a sing-song Gullah accent. I looked closer at his pickup truck, with a jumble of empty crates in the cab.

“Are those crab traps, sir?”

“Vegetable bins. Been up to the food bank in Yemassee with a load of my tomatoes.”

I stepped over the median to shake his hand.

Those born and bred on the Sea Islands have reason to be wary of people from off, especially real estate developers. This leads to the misconception that Gullah culture is dying. Far from true. Without the rich heritage of language, music, and cooking of the Gullah Geechie, descendants of the first Africans to toil here, the Lowcountry would be a poorer place altogether. Harriott Pinckney Horry owned slaves who worked in her fields and kitchen; she certainly wasn’t out there growing or preserving the tomatoes that appeared in her journals. We wouldn’t have most of the dishes that came after, either.

Before retirement, Chaplin, 73, was a civilian employee of the U.S. Marine Corps on Parris Island, and then brick mason at Hunting Air Force Base. With his wife Harriet, a nurse and daycare operator, Chaplin now owns a country store on Storyteller Road, a byway between the leased fields and labor camps on Saint Helena. They sell mostly dry goods and snacks to the Frogmore community, although later in the afternoon when I turned up there, a sign in the window advertised live crabs, and bushel baskets of fresh picked okra sat on the floor near the refrigerator case. His T-shirt and glasses splattered with pluff mud, Chaplin had returned with shrimp in his cast nets from the creeks feeding Port Royal Sound. Unflustered, he took me out back to look at his own fields, 20 acres surrounded by mature pecan trees. He also grows squash, broccoli, collard greens, and corn. What doesn’t sell in the store gets donated for hunger relief. Yemassee is the nearest distribution center for the Lowcountry Food Bank network.

“How many rows of tomatoes?” I asked.

“I don’t got too much, about 16 rows here and 10 rows there,” he said. “Nothing big, just to keep me active.”

“Have you been farming long?”

“I been doing this since knee high.”

“How long has your family been here?”

“Oh, hoo! Quite a few years. About a hundred years back. Most of my folks, grandparents, from Cedar Grove. That’s right on the island, too. The rest of them I don't know. We go back, we don’t know where. We say ‘longa go wit all that.’”

Chaplin had a limp, so we took our time between the rows of tomatoes, a few here and there on the ground rotting, weeds taking over the sandy soil. Chaplin explained he tested every other year, taking samples to Clemson Coastal Research and Education Center for advice on pesticides and fungicides. He let me pick a few red ones off the vines to take away. Chaplin pulled out a handkerchief and wiped his forehead.

“See those greens, that brown ring on it? I got to get them before they start ripening up. I done pick them twice this week, haven’t watered in about two days. So hot.”

Clouds piled up on the horizon as the sun dipped below the palmettos.

“Most of time you see rain all around in a circle, not a drop here. I ain’t going to complain, we still have it good compared to other places.”

“That’s for sure,” I said. “How do you eat a tomato?”

“I eat it natural, put a little ranch on it, slices of cucumber, that make a meal right there.”

We headed back to his truck.

“I don’t know why we grew so much this year, gol-ly. I’m waiting for the kids to decide they want to take over. Had six, four still living. I probably give it up next year. Time bring on changes, right.”

Chaplin gestured toward the distant rumble of tractors.

“I’m a peanut, just a little peanut to what they plant.”

On leaving Saint Helena, I stopped at a stand closer to Beaufort owned by another Gullah farmer and bought extra tomatoes — pretty good slicers as it turned out — for dinner with cousins up in Charleston. Behind the bins holding cabbage and peaches was an acre-long hoop shed where a Latino worker sorted seedlings. He looked up and waved. Then, as I hesitated over a display of canary melons, face flushed to near heat stroke, he took the tomatoes out of my arms and handed me a slice of the cooling melon.

“Es mejor, muy delicioso.”

My car smelled of rind and kindness and tears.

“I guess we kinda like to grow the funky stuff,” said Matthew Horry.

A husky man with unruly brown hair, he leaned over a dog crate topped with propagation trays holding lumpy, wrinkled, oddball tomatoes in the Chaparral RV camper he and his fiancée, Ashley Loponte, temporarily occupied on a rural lot outside Walterboro, South Carolina. Horry, 31, is a biological science technician who specializes in landrace and heirloom seed increase for the U.S. Vegetable Laboratory at the Clemson Coastal Research and Education Center. His personal pursuit is a half-acre organic plot of experimental cultivars. The couple calls it Kindlewood Farms, their expansion dream after selling a starter home and backyard garden of two raised beds.

Their hothouse is a repurposed trampoline. A wine cooler serves as a storage unit for ripe produce. They favor compost and fish emulsion over pesticides and fungicides. Their dog Gordon, a bouncy Labrador-pit bull mix, deters critters as much as the electric fencing.

Ashley Loponte opened the camper door, letting in the heat and light of early July. Her cars keys hung from cotton-knit jalapeños with googly eyes.

“I like your key chain.”

“That's her passion," said Horry. “Mine's tomatoes, and hers is peppers. We’re a Solanaceae family.”

“Before we closed on the land, we were at my mom's house, so I started a whole bunch of things without Matt's consent in the garage,” said Loponte. “That's why everything is super early this year. We're the first to bring heirlooms to the market because I had to get motivated.”

“It’s a shared passion,” said Horry. “A consuming passion.”

On weekends, they sell at farm markets in the greater Charleston area. Horry obsesses over the catalog from Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, which preserves the South’s rarest varieties, including “Aunt Lou's Underground Railroad Tomato,” from original seed stock reportedly carried by an unnamed black man who crossed to freedom from Kentucky.

“The heirlooms we have are Martha Washington, Amish Paste, Radiator Charlie’s Mortgage Lifter, Striped German, Red Zebra, Black Cherry, Valencia, Solar Flare,” Horry said, sorting through the flats. “We fought about this a lot. Tried to scale it down this year, keep only a few varieties.”

He shrugged, acknowledging his inability to resist planting weirdos. “The homegrown tomato is something that piqued my interest. It’s one of those vegetables, if you’re fortunate to grow up eating them from the garden, you’ll not be satisfied with the supermarket kind.” He picked up a mottled yellow and purple tomato and handed it to me.

“We have a whole row from breeder Bradley Gates. These are called Blue Berry. They're not heirloom, but they are open pollinated. It's a little bitter when not fully ripe, but still gorgeous. The word heirloom, that's been overused. What I'm looking for is flavor and character.”

I took a bite.

Like tomato pop rocks blowing up in my mouth.

Sadly, not sized for a sandwich.

Horry cut a juicy slice of Cherokee Purple. Only a devoted gardener could love this ugly bruise cultivar from Tennessee, also saved from extinction by happenstance and amateur breeders. Right then, I stopped looking for a slicer that would do justice to Ernest Matthew Mickler’s kitchen sink recipe. It had a tingly balance of sweetness and acidity, a flavor that made me want to shout, “Roll up your sleeves, Southerners.”

He sold me one for $2.

“So, hey, wait a minute. Are you related to the Santee Delta Horrys?” I asked.

He nodded.

“I’m a descendant.”

“Okay, that’s crazy. I’m related to Francis Marion.”

Loponte looked bewildered at the two of us, grinning ancestry geeks.

“Our ancestors fought together in the Revolution,” I said.

They included the husband of Harriott Pinckney Horry, early tomato adopter.

Not long ago, I bumped into my cousin Edward Seabrook’s widow, Lucy, on the street in Charleston. Folly was no longer a sleepy buffer island. She still owned the beach house but was deeding it to one of her nieces.

“What happened to Edward’s books?” I asked.

She winced, and then shrugged, apologetically.

“Oh, we threw them out.”

At the end of that childhood vacation, I snitched The Prince of Peril and Thuvia, Maid of Mars, and stuffed them in my suitcase hoping Edward wouldn’t miss a few paperbacks from his science fiction collection. (He probably did.) They still sit on shelves in a spare bedroom in my house. Edward Seabrook’s formula for a great tomato has also been lost to the ages.

While we now have so many other fanciers, seed savers, scientists, and botanists working on reviving the flavor of the slicer, we remain deeply compromised in our hunger for a fair — and fairly decent tasting — tomato. The Coalition for Immokalee Workers is collaborating with the Student/Farmworker Alliance on another action to boycott Wendy’s. Publix is still a Fair Food Program holdout.

Before Edward Seabrook went to the garden beyond, I began to take serious interest in Southern food traditions, and it occurred to me to ask about his mystery soil mix. He could transform my abrupt, gender-bending name into a soft, elegant crescendo, resonating on the scale between Howard Chaplin and Bubba Crosby. I loved hearing Edward talk. Few people alive still have that accent. It also meant I didn’t always catch everything he said. He mumbled a series of numbers, some mutant formula, and thinking about it now, I wonder if it was the heavy phosphate favored by Crosby.

Then again, Edward could have been speaking Martian, for all I know.

Angela Navarette and Ignacio Lopez (whose names have been changed to protect their identities) are currently in Virginia and will be there until November when they return to Immokalee, where the planting cycle will start all over again. The matado’s knees are a little better.