The very best of Southern music has always been created by people of strong vision, people who want to break new ground, sonically and culturally. Around such seminal figures — producers like Jim Stewart and house bands like Booker T. & the M.G.’s — artists coalesced, and they gave the world new music that spoke to changes in Southern culture. Southern hip-hop magic is no different, and if you’re looking for the visionaries behind it, your search will always lead you to three men from Atlanta — Ray Murray, Rico Wade, and Sleepy Brown — known to the world as Organized Noize.

Story by Dr. Joycelyn Wilson | Photographs by Zach Wolfe and Jason Thrasher

I am an ethnographer by trade. In other words, I study culture — specifically, black culture in the American South.

More specifically, I study the ethnography of hip-hop music in the urban South.

In every ethnographic study, researchers like me wind up looking for an origin point — the time when a new culture emerges distinct and apart from the forces that created it.

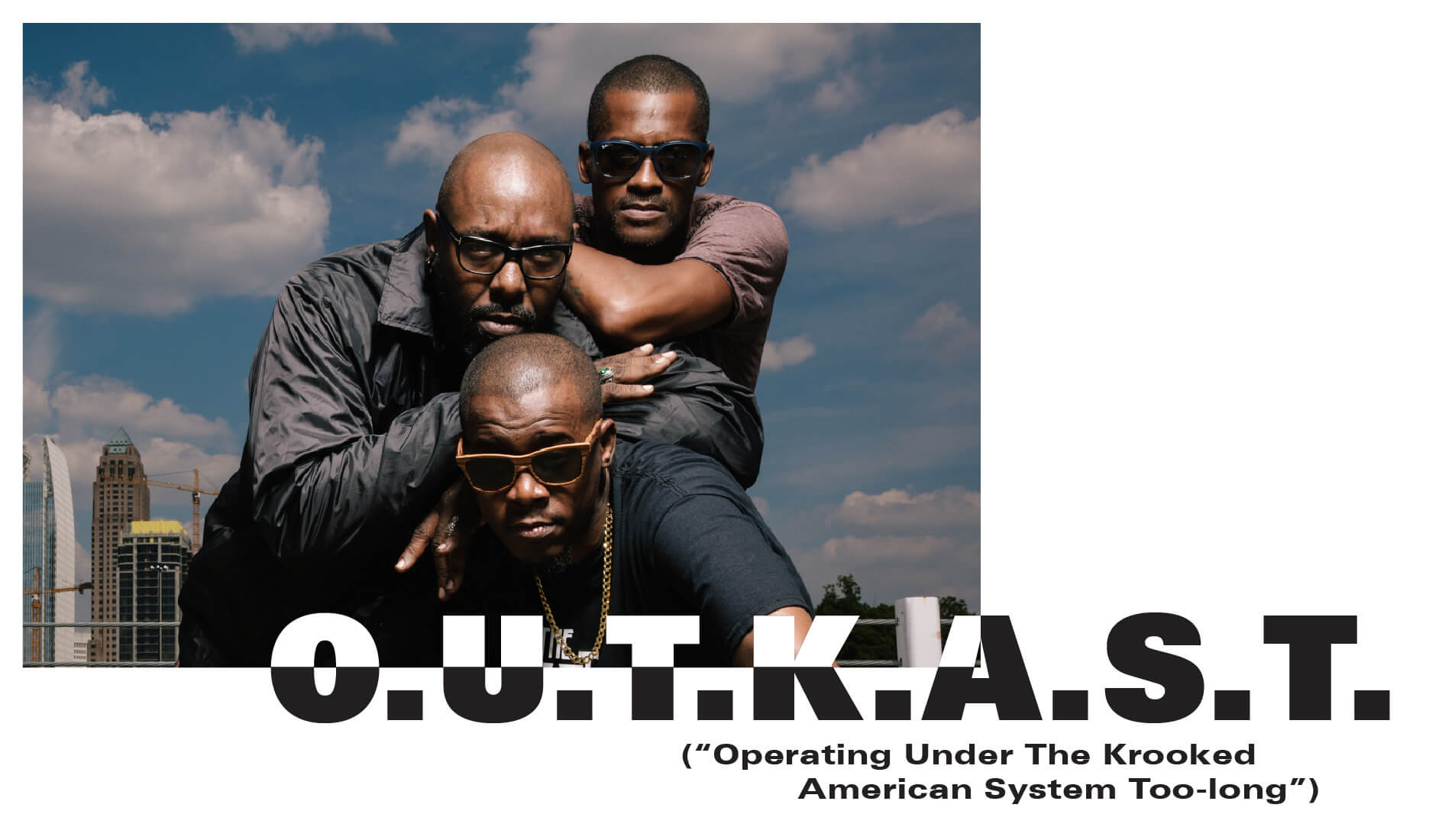

So, what were the forces that helped create a distinctly Southern hip-hop culture? The origin point is clear: It was the release of Outkast’s first album, “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik,” in 1994. But Antwan “Big Boi” Patton and Andre “3000” Benjamin did not, on their own, create Southern hip-hop culture. Musical ethnography demands you look behind the artists and learn about the producers and sound creators who helped the artists create the vision. It’s a common theme in Southern music. For instance, every deep look at Southern soul music eventually leads to the multiracial house band at Memphis’ Stax Records, Booker T. & the M.G.’s. Southern hip-hop follows the same model. And if you study it, it will always lead you to three men from Atlanta — Pat “Sleepy” Brown, Ray Murray, and Rico Wade — a team called Organized Noize Productions.

From the mid-1990s forward, Organized Noize wrote and produced for TLC, En Vogue, Ludacris, Mista, Society of Soul, Goodie Mob, and, of course, Outkast. Brown, Murray, and Wade have remained at the center of hip-hop culture ever since. Their presence was felt during the sold-out Outkast reunion tour that dominated the summer of 2014. The 2016 Netflix documentary, “The Art of Organized Noize,” documents their rise, influence, challenges, and legacy. (If you claim to be a student of Southern culture, then it’s a must-watch.)

And last year, Organized Noize and its Dungeon Family collective of musicians and MCs orchestrated one of the most legendary reunion performances in hip-hop history at the ONE Music Fest in Atlanta. The show began with a recitation from Big Rube, followed by Cool Breeze’s performance of “Dirty South” and Backbone’s “5, Deuce, 4, Tre.” Then, Lakewood Amphitheater exploded when Andre 3000 came out wearing his gold grill to do classics like Goodie Mob’s “Black Ice” and Outkast’s “Hootie Hoo” with Big Boi. Killer Mike performed "The Whole World" along with Outkast. Today, Organized Noize has production credits on “Kill Jill,” the Southern rap manifesto on Big Boi’s new album, “Boomiverse.” The three also just released the first record ever under the Organized Noize name, an EP simply titled “Organized Noize.”

For the last two decades, the sound of American black music – rap, in particular – has lived in the South, and especially in Atlanta. Organized Noize sits at the core of this culture. I have studied the math and science of their soulful sound, creative innovations, and chart-topping hits for the last 20 years – first as a journalist and now as a scholar..

I have concluded that their marks on hip-hop music and culture are ubiquitous. Organized Noize is just as important to Southern hip-hop as Booker T. & the M.G.’s were to Southern soul.

I study Southern hip-hop culture because it is my culture. I know that Pat Brown, Ray Murray, and Rico Wade captured lightning in a bottle because I grew up in the same Atlanta neighborhoods as they did, and in the same era.

I was born in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and raised in SouthWest ATlanta — the SWATs, as it was known. In the early 1970s, my folks joined the migration of other African-American Alabamians to destinations like Atlanta. We were in search of educational and economic opportunity in the city where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was born and buried.

My mother, sister, and I touched down in Atlanta in 1981, on the heels of the Atlanta Child Murders, the election of Civil Rights Movement icon Andrew Young as mayor, and an emerging African-American middle-class. Leaving just about everything behind, we were the last of a family full of aunts, uncles, and cousins who had already relocated to the Black Mecca.

I was 9 years old. My roller skates and I found ourselves living in an all-black neighborhood, indulging in an all-black music experience called rap, and attending all-black elementary, middle, and high schools with the cool kids: Khujo, T-Mo, Ceelo, and Gipp from Goodie Mob. Backbone, Cool Breeze. Chilli from TLC. Shanti Das, DJ Toomp, Emperor Searcy, Kawan Prather, and many others.

Our schools were named after African-American leaders and educators, and our weekends were reserved for football, skating at Jellybeans (as depicted in the film “ATL”), and being in the thick of citywide talent shows that were often dominated by a dance crew named Guess.

Organized Noize’s Brown and Wade were part of Guess. They were “teenage celebrities” even then. Before teaming with Murray as the producers who first gave Outkast the opportunity to say something, these two dominated talent show competitions throughout the city with their yeek-dancing and pop-locking routines. They sat at the forefront of creating the high school hip-hop peer network that would later dominate the sound and direction of the culture.

Organized organized a following in high school before they organized the noise of contemporary hip-hop and R&B. We were products of the same Atlanta Public Schools/Fulton County Schools high school network that birthed the practitioners, pioneers, producers, and politicians that laid the foundation for Atlanta hip-hop and its post-Civil Rights Movement aesthetic. I know of no other Southern scholar with this kind of unique relationship with the elements that went into the design of Atlanta hip-hop. God only knew what being in the thick of things would lead to for me: a career as a cultural critic with a unique perspective for documenting the influence of the likes of Organized Noize, using my own experiences to interpret their indigenous history in Southern hip-hop and within the global canon: this constantly evolving, location-dependent corpus of artifacts, stories, and memories produced by hip-hop-inspired performance.

Almost all of these stories originate in communities of color — marginalized by racial segregation, cultural colonization, and gender inequality. Out of them, we get disruptors like Organized Noize Productions.

How so?

It’s a beautiful spring afternoon in Atlanta, and I am in a special place — the offices of the Andrew Young Foundation — eagerly anticipating the arrival of Brown, Murray, and Wade.

“Perhaps we can move this chair over here with the other two chairs,” I suggest to photographer Zach Wolfe. I point to a wine-colored antique leather armchair that is against an adjacent wall. “This way, we can get all three of them seated together in front of the African statue.”

The statue, carved of cherry wood, is of a Zimbabwean warrior. It stands tall in a corner like it’s protecting the room. It can’t be missed. The two chairs next to it are also from the African continent. The seat is made of a brown suede cheetah print, and the back is South African ostrich leather. Heads of lions are carved into the chair’s arms. Together, the chairs and statue decorate the office’s glass wall.

The main wall is adorned with framed photos. One in particular is of Young, when he was mayor, shining Muhammad Ali’s shoes. Hosea Williams stands close by smiling. Another is a striking candid of when 20-something Andrew Young first met a young Martin Luther King Jr. It was taken in the spring of 1957 at Talladega College. Young and King were invited panelists for the college’s religious emphasis week, organized by the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.

“I like to say I was invited as a backup,” Young says, laughing. “Just in case Martin didn’t show up.”

Despite our common histories, I had never gotten the chance to converse with all three members of Organized Noize.

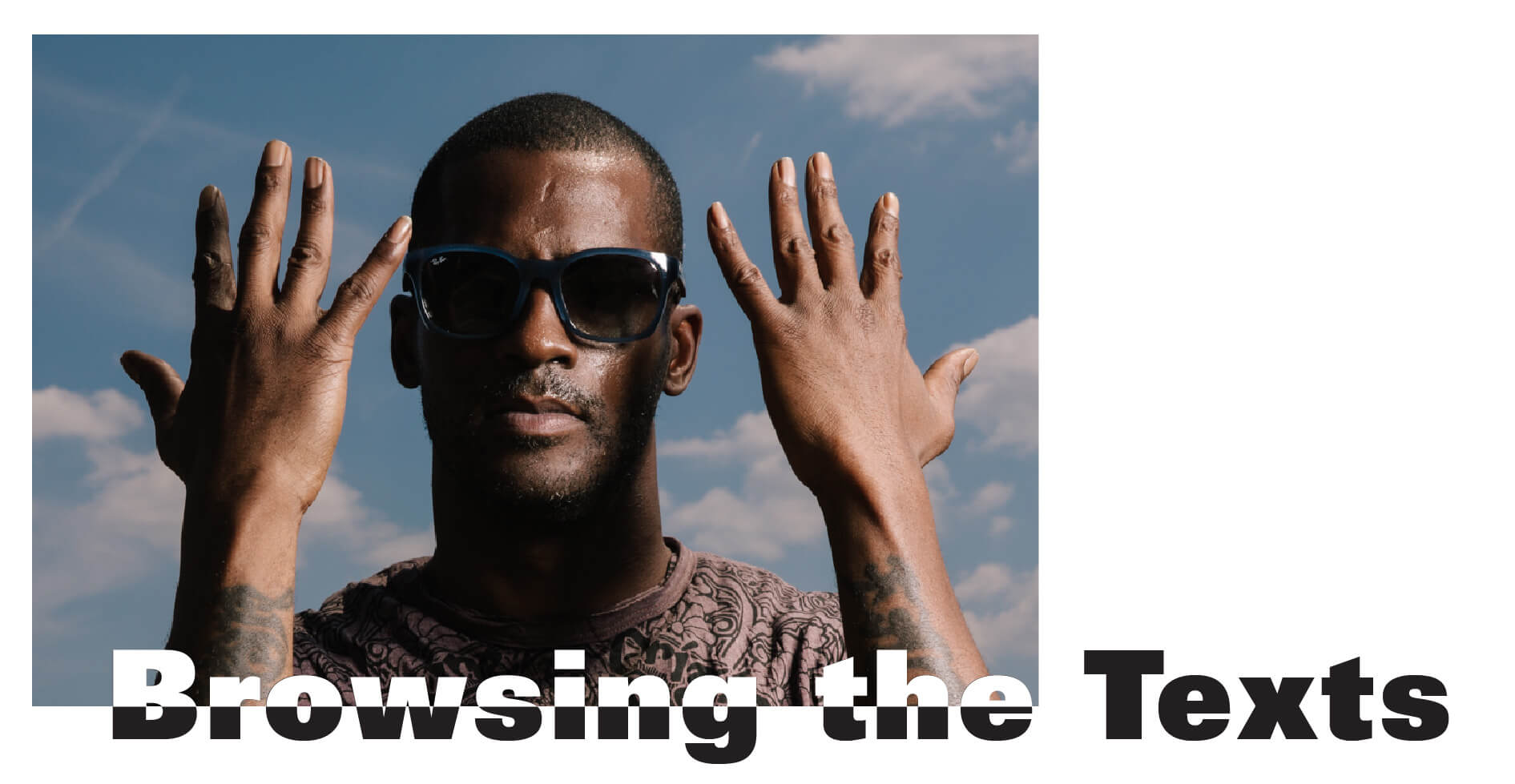

“The guys,” as manager Orlando McGhee refers to them, arrive separately. Ray Murray first. He and I went to the same high school, but we never actually met. I’d heard through the grapevine Murray had watched my TEDx Talk on the Outkast Imagination one night while working at Stankonia Studios. But never had we shared a conversation.

Ray had close to 45 minutes to look around the office space solo before his partners arrived. Young’s museum of original photographs, autographs, honorary degrees, and awards makes history tangible – literally. But it was Young’s extensive book collection that caught Murray’s attention the most. Leaning down toward the bottom of the bookshelf, he points to the “Eyes on the Prize Reader.”

“We’ve moved into a time when this whole book is a slogan now. It’s a meme, a tweet,” Murray says, laughing sarcastically. “That’s impossible.” Then, as he walks toward Young’s wall of photographs, the father of six says, “‘Trap or Die’ is not the same as ‘By Any Means Necessary’!”

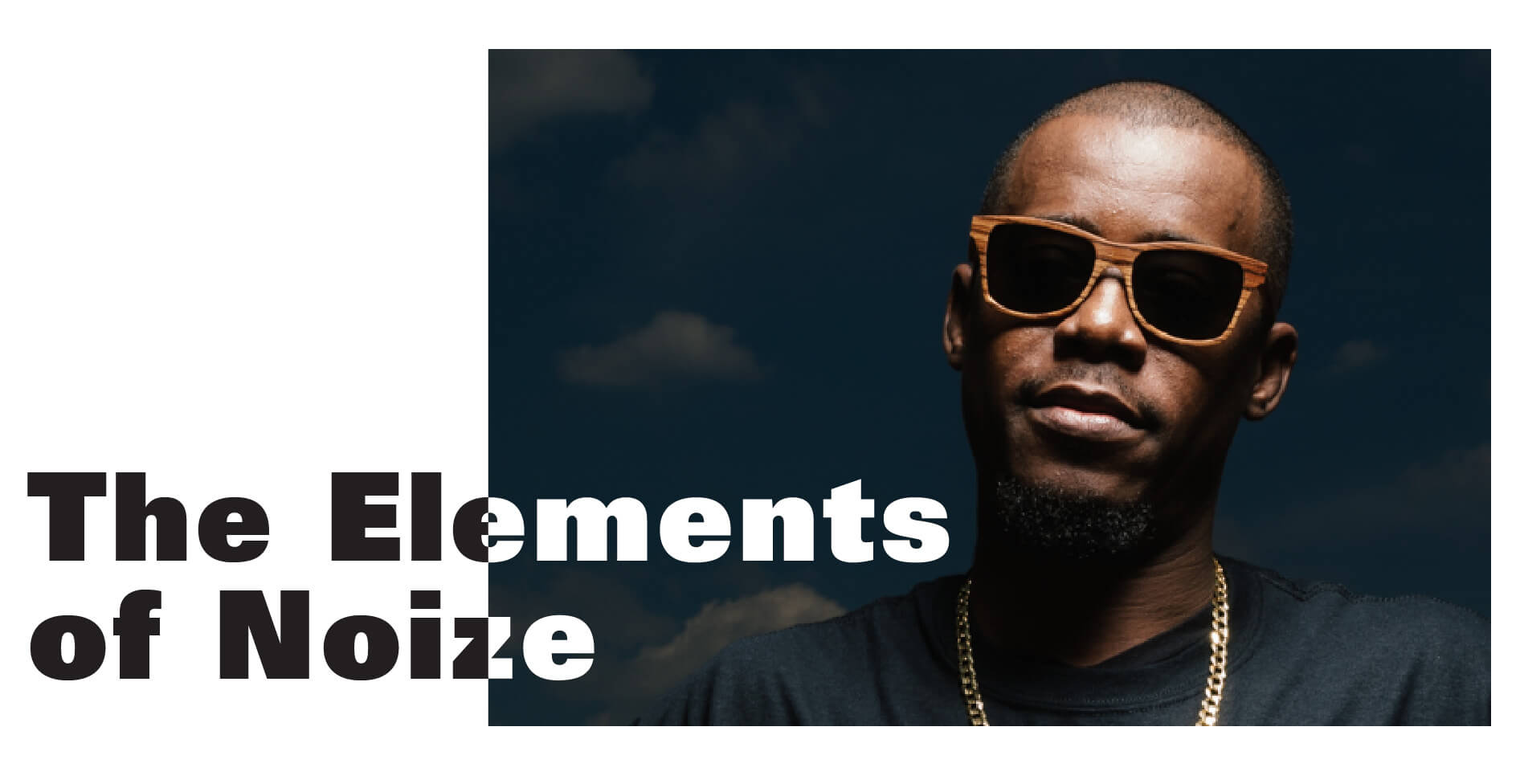

Sleepy Brown arrives next. After greeting everyone in the room, he immediately turns to Ray to express his thoughts about the mix-down of a song they are finishing up.

“We gotta get this done ASAP,” the smooth-voiced crooner declares. He’s the son of Jimmy Brown, saxophonist and lead vocalist of the ’70s funk band Brick. Brown spent the summer of 2015 touring with Outkast as a background singer/performer. We've been good friends since I was 15 years old.

While waiting for Rico Wade, Sleepy cracks a joke on his longtime friend.

“Don’t be surprised if he walks in here with a bag of food,” Sleepy laughs. “He gon’ always stop and get him something to eat.” Rico does arrive shortly thereafter, but without food — just a can of San Pellegrino Limonata. The last time we spoke was in 2003, when I interviewed him for XXL magazine’s “Show & Prove” column about a group he was working with called Da Connect. It included his cousin, then known as Meathead, who the whole world now knows as Future.

“I like those shorts,” McGhee says to Rico.

“I don’t know if I like those shorts,” Murray jokes.

It’s clear from their interactions the trio is more than a production partnership. They are brothers. There’s also nothing special about the shorts. They’re black, knee-length. The socks, however, are the eye-catcher of Rico’s ensemble. They are dark purple, half-calf, with “NAMASTE” written in big white letters up each side.

I often say the story of hip-hop is the story of the sample.

Organized Noize takes this claim and turns it on its head, in a good way. They organized a new “noise” (pun intended), a soundtrack for Southern hip-hop, a different prescription for healing the souls of black folk in a post-Civil Rights Movement, hip hop-inspired world.

Out of sheer necessity and creative ingenuity, the early developments of hip-hop sound is built on the principle of taking existing music from earlier eras and genres to build innovative new soundscapes – often creating a message completely different from what the original musicians intended. But rather than merely sampling — or should I say cloning the sound patterns of existing music — Organized Noize aimed at reinventing the spirit of black music, the feeling one gets when listening to a song.

Pull Goodie Mob’s “Soul Food” album, for example. To set it off with the song “Free,” which flows into “Thought Process,” the guys did not merely sample the music of gospel great Mahalia Jackson’s “Trouble of the World.” Instead, they reimagined the core spirit and message of the old Negro spiritual and re-presented it to a generation of kids (myself included) who, in 1995, were living through economic and educational (re)gentrification, while others were capitalizing on it and prepping for the 1996 Summer Olympic Games. This is the spirit that went into Cool Breeze’s description of the Dirty South.

I've come to think of Outkast’s “Southernplaya,” which came out in ’94, as an invitation to experience a psychological migration back home to the deep Dirty South – both musically and lyrically. And then Goodie Mob’s “Soul Food,” released a year later, is the spiritual nourishment that is necessary once you get back home. Even the huge pop hits produced by Organized Noize — TLC’s "Waterfalls" and En Vogue’s "Don't Let Go" — are designed to vibrate to a higher self. Their music was ahead of its time. They created instant classics that immediately changed the sound of rap music and ushered in a new hip hop vibe.

“We most definitely combined hip-hop with organic live instrumentation,” says Rico. “We couldn’t abandon hip-hop. All the time we were pushing these envelopes. We understood there was a fine line we had to tread. But we wanted to bring to hip-hop the soul and the spirit of live music that’s organic to the South. From studying music and sound, we realized if we use the analog gear, it will give the feel of a sample but with more clarity.”

The trio typically looks to soul music to generate the clarity Wade references. A key inspiration for them is Earth, Wind & Fire, the soul band founded by Memphis-born Maurice White and named for the three essential elements. Beyond their love of White’s creative vision, those three elements themselves are an appropriate metaphor for the chemistry between the three members of Organized Noize.

On June 26, 2016, Sleepy posted on his Instagram page a black-and-white candid of Organized Noize working in the studio on their self-titled EP. A keyboard is in front of him. His fingers are on the trackpad of his MacBook Pro. To his right is Ray. He, too, is on his Mac, a Black & Mild cigar hanging from his mouth. To Sleepy’s left sits the always energetic Rico. He’s on the phone, and just like his partners, a MacBook Pro is in front of him.

When I saw the post, I commented “Earth, Wind, and Fire … in that order.”

Sleepy responded, “I like that.”

In Netflix’s documentary film, Big Boi describes Ray as “the beatsmith,” who “stays in some kind of [software] program.” Essentially, he grounds every song. He’s earth.

Then there’s Sleepy. He’s described as “the chords man,” the “melody maker.” His personality is a quiet storm; his falsetto voice resonates like, well, the wind.

Rico is characterized as the “808 [drum] guy.” He’s the mouthpiece, the energy, the one who closes the deal. He is the fire.

And just as Earth, Wind & Fire, the band, gave black people a sense of resilience and determination through their music, Organized Noize elevated the identity of a region that suffered from a bad case of “New York-ism” in the early ‘90s. This identity they built for Southern hip-hop artists and fans has remained etched in the minds of those who are from Atlanta, and it is quickly adopted by transplants.

From their early productions to current music such as “We the Ones,” the first song on their new EP, “Organized Noize,” Brown, Murray, and Wade have never departed from speculating about their community’s avenues to freedom. You can track it all the way back to the second cut on Outkast’s first album, “Myintrotoletuknow.” Not only did that track introduce the world to Outkast, the group, but it also introduced us to ideological disruptors on a quest to gain knowledge of their black, Southern selves while disturbing the previous sound of classic hip-hop.

Recall how “Myintro…” begins after Dee Dee “Peaches” Murray invites the listener into an otherworldly Southern space:

For East Point, College Park, Decatur, and the SWATs

We got that Southernplayalisticadillacfunkymuzik for yo' trunk

And it's fat like hambone, and tight like gnat booty

So let me take you deep, straight to the point

’Cause it ain't nothing but king shit, all day, n’day

As “Myintro…” rolls in, take a moment to study its drum patterns. The vibe is reminiscent of James Brown’s “I Got the Feelin’.” Organized Noize does not, however, use a direct sample from James Brown, but rather a slowed down re-creation of the music’s sensations. Once the melody is set, a young Big Boi starts with a reflection on his community’s colonized past. He raps:

Time and time again, see, I be thinking about that future.

Back in the days when we was slaves, I bet we was some cool ass niggaz.

After evoking cultural memory, Big Boi brings his listeners into a contemporary critique of gun violence.

But now we vultures. Slam my niggaz back out.

To make his ass black out. Or even pull your fuckin’ heater

To make his whole crew believers.

Then Andre 3000 comes in to broaden his partner’s conception of time. “Time is slippin’ slowly but surely,” Dre raps, as if to say, “Time is of the essence now. The world is changing. Our community is suffering. We gotta do something.” Although he’s worried, Dre chooses resilience when he raps, “I wipe the boo boo from my brain, then I finish up my rhyme.” In other words, he chooses the freedom that Sleepy describes above in the hope that others will be inspired through the music to “escape” – to bounce back in the face of personal and social challenge. The musical and lyrical set-up of “Southernplaya” is therefore an intellectual one.

The song’s hook, however, is perhaps the best example of the artistic influence behind the messages in Organized Noize’s productions.

In soulful, bluesy drawls, Big and Dre sing-rap, “If you smoke a dime, then I’ll smoke a dime.”

The surface reading of that lyric is simplistic — they’re just talking about smoking weed (marijuana was often sold in $10 “dime bags” back in the ‘90s). But listen more deeply, and you will hear “the dime” become a metaphorical object used by Patton, Benjamin, Wade, Brown, and Murray to invite listeners into a reciprocal exchange of reasoning and problem-solving. They want their community figuratively to inhale and exhale ideas that lead to deeper understandings about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness in a city described (often erroneously) as “too busy to hate.” They want us to understand the experiences of African-American men coming of age in a city awash in a cycle of overwhelming gentrification. The Buick Regal that Dre is “rolling reefer out of” is actually the learning environment where these conversations happen. Beneath the surface of literal commentary, the message becomes that if you, the listener, will engage with this knowledge or this “game of life” we’re spittin’, then the MCs, producers and teachers (Outkast and Organized Noize) will reciprocate by providing food for thought.

No seeds, no stems. Straight, no chaser.

On May 5, Brown, Murray, and Wade released a self-titled EP called “Organized Noize,” which features Joi, 2Chainz, and Big Boi. For years, they’ve been known for producing music for others, but these seven songs are their first as a collective. Perhaps they want to test the waters, to take the temperature of their audience. Or maybe the compilation has little to do with us, the listeners and fans, and more to do with an ongoing commitment to building the cultural archive they’ve been depositing into since Wade and Brown were winning trophies for yeek-dancing and Murray was playing tennis in Atlanta’s West End.

Murray credits his father with two things: teaching him how to play tennis and instilling in him a sense of black pride and identity. He calls it “West End fundamentalism,” referring to a historically black Atlanta neighborhood.

“Taking all of that to southwest Atlanta, I realized it’s the Andrew Youngs and the Maynard Jacksons that made all of this possible. It’s Hosea Williams; it’s Ralph David Abernathy; it’s Julian Bond; it’s Marvin Arrington. Them and so many others moved the city in a way to allow access to opportunities for all of us. They made us leaders.”

There’s no question Andrew Young has spent most of his professional life showing up and inspiring new generations of leaders to show up – even those in music and entertainment, like Organized Noize. To hold this conversation at Young’s foundation office is to bring forth a respectful look at black Southern traditions – past, present, and future. Being there weds cultural memory with moments made possible by people’s vision for racial equity and economic harmony in Atlanta and beyond.

“I saw myself as a part of his campaign early on,” Rico remembers. “I had a button when I was in middle school that said, ‘Young for Atlanta.’ I actually thought the button was really about youth being for Atlanta. Ya know, like young people for Atlanta. I was young and for Atlanta.”

The early 1980s were a peculiar time for black people in Atlanta. Although there was a movement to situate the city’s African-American population in economically and politically beneficial roles, the city was going through its own bouts with Reaganomics.

“The ’80s were different for us,” Ray asserts. “Everybody wanna reflect on it like it was a good time, but the economics of the ’80s were really messed up in the city. All the jobs were changing from industrial to technical. So, to survive during those times, you had to learn a sense of determination, like Rico described learning for himself.”

Rico Wade cultivated his hustle early on – even before he joined Guess. He was a talented young football player. But his mother, like many others in his community, could not pay for him to be on the team.

“One day she got a call from the coach,” Rico recalls with animated zest. “She was like, ‘I can’t pay for you to play, but the coaches want you to play.’”

Ric, as his close friends call him, decided he wanted to play football but also help out his mother by earning his keep. He started making money carrying out the trash for neighbors who respected his innate desire to win.

“When those coaches told me to be at that bus stop, I was at that bus stop. All I had to do was show up! I teach this to my son, because it’s not as obvious when dealing with the millennials.”

As fathers from the first generation of hip-hop children, Wade, Murray, and Brown implore their kids to take advantage of their opportunities while understanding they live in a world still battling racism, poverty, and homophobia.

“It’s different now,” Ray begins. “In my opinion, this generation lacks an understanding of the history. If you were born with Barack Obama as president, you don’t understand a time when ya uncle told you not to be at Stone Mountain because they don’t like Negroes up there. They are like, ‘What are you talking about, Dad?’ It just doesn’t resonate. They think it’s hatin’.

“It’s not hatin’. It’s history.”