Daniel Edwards illustrates the unique burden black police officers carry in a striking photo essay, “Black Outlined Blue.”

Photographs by Daniel Edwards | Words by Tim Turner

Daniel Edwards has loved law enforcement officers from the cradle. He has also become enraged by how many of them have put people who look like him in their graves.

His healthy contempt for bad cops comes from being a young black man in America — and having eyes. His love of police officers, however, comes from their first loving him — a mother who was an officer in the Aurora, Colorado, police department, and his father, who was an officer with the Denver Police Department and later with the U.S. Marshals Service.

Raised in such a household, Edwards fully understands the burden black cops carry today. Bad cops have placed them in a bad light, a light he never witnessed at home. The public service of black cops, for some, has become equal to aiding the enemy. That’s why Edwards took up a project he calls “Black Outlined Blue.” He wants to tell the stories of black cops in the Atlanta Police Department who deal daily with the duality of life in their skin and life in their uniform.

“That's at the core of my project,” Edwards says. “That kind of that conflict and perspective. Especially that conflict within myself. So, instead of settling into that anger, and still trying to figure out how to love my parents, and knowing what they did, and have done, it all kind of evolved into that question: wondering how a black person in America could be an officer today. That's what got the ball rolling with the project.”

Eric King

“Once I made the decision to move to Atlanta and actively pursue a career in law enforcement, my racial ‘identity’ and my job became co-dependent. I treat people different than the two bad encounters I … had with police growing up. Whether I’m in uniform or in civilian clothes, people speak and ask how I am doing, which consistently reminds me that even though I have a job to do, I’m not hated.”

He started at home, with his parents, asking them why they do what they do as police officers, and what has kept them in uniform. Edwards found the talks with his parents instructive because, he says, “there had been this gap in understanding [between him and his parents] that made room for me to kind of develop this hate for the police over time.”

His simmering contempt might come as a surprise to people who know Edwards and his parents. They might assume Edwards should have a staunch affinity for the law and those who enforce it. But they would be wrong.

“There is this notion that I have this black-and-white view of what is right … when it comes to the law,” Edwards says, “what is deemed as okay, and what’s not okay. And that's just not true. Not everything that’s right is legal, and vice-versa.”

Beyond the assumptions, Edwards said the most difficult part of capturing “Black Outlined Blue” was anticipating the reaction to it. Having grown up with police officers as parents, he has always seen their humanity on display. But he doesn’t want his positive portrayal of officers to be interpreted as a counter-narrative to the efforts of those in the Black Lives Matter movement.

“I didn’t want the project to be pigeonholed into a kind of specific narrative — like, ‘Oh, cops are people, too,’ or like, ‘They aren't all bad.’ You know, that all-cops-aren’t-bad type of deal. We know those things, and they’re pretty obvious.

“What I find interesting is this dichotomy of identity. There are certain professions that become a person's identity, like it's more than just a job. Like being a firefighter or a doctor or a lawyer or something like that. It's not just what you do; it becomes who you are. And so this duality of identity, of being an officer and being a black person in America, is something that interests me. And that's what informs this.

“We know they are people like us. I want to do something deeper than that. Like, how do you be a person and a cop, too, and be black? My parents are still that and will always be that. They were my example.”

Edwards got the project rolling by earning the trust of one APD officer and then building a network. Wholly through word of mouth and cultivating relationships, he brought more of Atlanta’s black cops into the project. And he discovered, by building those personal relationships, that his parents were not anomalies.

He shot images of APD officers at locations that meant something to them, and asked them to write about their own experiences. Their words cover the motivations, the obstacles they face, and the realities of being black cops.

“It's all been accurate, because I'm not infusing anything in the project,” Edwards says. “This project is really centered around their own words. I asked them questions. I want to get to know them and want to get to know their journey as officers, to [know] what conflicts and things have arisen from them being … black and also being in this role.”

Edwards discovered a shift in attitudes among the officers. The notion that cops reflexively “back the blue,” irrespective of the situation, isn’t really a thing anymore.

Aerica Sauls

“My racial identity and my identity as an officer are equal. Being an officer does not stop me from empathizing with and understanding my fellow African Americans when there are constant reminders of injustices that happen to my people. If anything, being an officer while being conscious of what goes on in today’s society allows me to do my best to bridge the gap and show the positive sides to being an African American police officer.”

“That was an assumption that I went into this project thinking about, too,” Edwards says. “The most common answer, throughout, all of them are saying none of them is going to put their livelihood, or their family's livelihood, on the line for an officer that was in the wrong, and they know that officer was in the wrong.” Edwards says the cops he photographed work hard every day to change that narrative — the one of absolute fidelity to their brothers and sisters in blue irrespective of innocence or guilt.

“The idea of being black in addition to being a police officer, to a lot of them, it's about being the kind of officer that they want to see,” Edwards says. “Kind of opposite of [the officers] they saw growing up.

“Others take the route of educating — being a visible kind of staple in the community, especially when it comes to youth interactions, and doing their best to change the narrative by being a living example,” he says. “And then there are some people that, when it comes down to it, it doesn't matter how someone is going to react to them. That they are there to do a duty and do a job, and they're gonna do it regardless of how people react to them. There are some people where it is a much harder narrative. There are family members who no longer speak to them. It’s applied a lot of stress to them on a personal level, but their sense of calling is more important, because at the end of the day, [their calling] trumps that.”

Phyllis White

“I grew up in one of the drug- and crime-infested neighborhoods of Atlanta. I remember seeing all of the young cool boys and girls hanging out on the corner at the end of my street. My siblings and I watched from our front porch a lot of partying and drug deals happen, which was sure to be followed by the police … chasing them down trying to clean up the streets in my hood, only to come back in a day or two and have to do it all over again. I always respected the police and never felt negative about them, but very thankful that they were coming back.”

Donald Hannah

“The most common response I’ve gotten has always been related to me being a black male in a profession that is often perceived to target black males. I am a black male that has been on both sides of the spectrum. I’ve been approached, questioned, and pulled over by police prior to my career as an officer, and even as an officer (off-duty). I understand the role of an officer and the purpose of certain actions. However, I cannot justify the actions of every officer that has sworn to serve and protect. It would be unrealistic to even attempt.”

Lortina Griffin

“I’ve been fortunate enough to pursue my happiness in a career that allows me to help and assist young adults who were provided a second chance in life to correct their wrongs and become productive citizens. In doing so, I am faced with rebuilding the relationship and trust between police and the community. I would be lying if I said it was an easy task to complete. But with respect and trust in the community, my career thus far has been successful.”

Courtney Murphy

“I was born here. I love my city. I am my city’s biggest fan. I decided to take the steps to become an officer because I wanted to help people and be able to make a difference. As an African American, being an officer was one of the rights we had to fight for. The first African American officers were all males. They were only to patrol the ‘black’ neighborhoods and could not arrest anyone white. So, as a female African-American officer, I understand and respect those who paved the way for me.”

Jarius Daugherty

“Initially, my family and friends were all confused as to why I would would choose this line of work, and to be involved in a system that has been historically used to imprison and suppress people that look like me. I, on the other hand, have always seen this decision as an opportunity to get involved in my community and attempt to build relationships between police and minority citizens, by teaching my family and friends how to interact with officers if necessary, and by teaching fellow officers how to speak to and relate to people of any ethnicity or community.”

LaDonna Collins

“I hope that the way I police will show people that all police officers are not the same and that we are not out to do harm. I explain to most people that almost every bunch has one or two bad apples in it. I love working with kids, and I feel like if I can change their perspective of an officer, then the cycle of ‘F’ the police will change (eventually).”

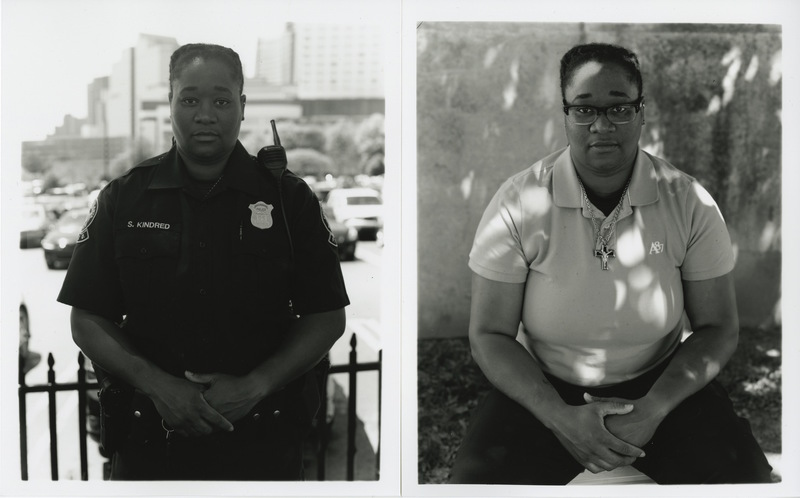

Shaketa Kindred

“I have seen a lot of different things. One that stands out the most [was] in February 2015. I received a call from dispatch about an accident. While in route to the location, it was changed to an accident with injuries [and] possible entrapment. Once I got to the scene, I noticed a female under the vehicle. The scene was very hectic, and [she] was trapped with a bad leg injury. I was able to talk with [her] and keep her mind off her pain until [the] Fire [Department] was able to move the car. Being able to assist those in need is one of the reasons I became a police officer.”

(Pictured in header)

Ashley Gibson

“I take pride in my uniform, but with that, there have been challenges in the present day, as scrutiny of police officers and their relationships with the community has come to a head. When I wear my uniform, I am not as a regular person with a family of my own. I am viewed solely as a police officer enforcing the laws of the state. To some, the profession is embraced as [the idea] police presence alone can provide comfort and safety. However, there are others who are not so convinced police officers can be trusted, and they do not want officers around unless necessary. I never like to hear about unpleasant experiences between officers and citizens, because I feel like I represent both sides.”