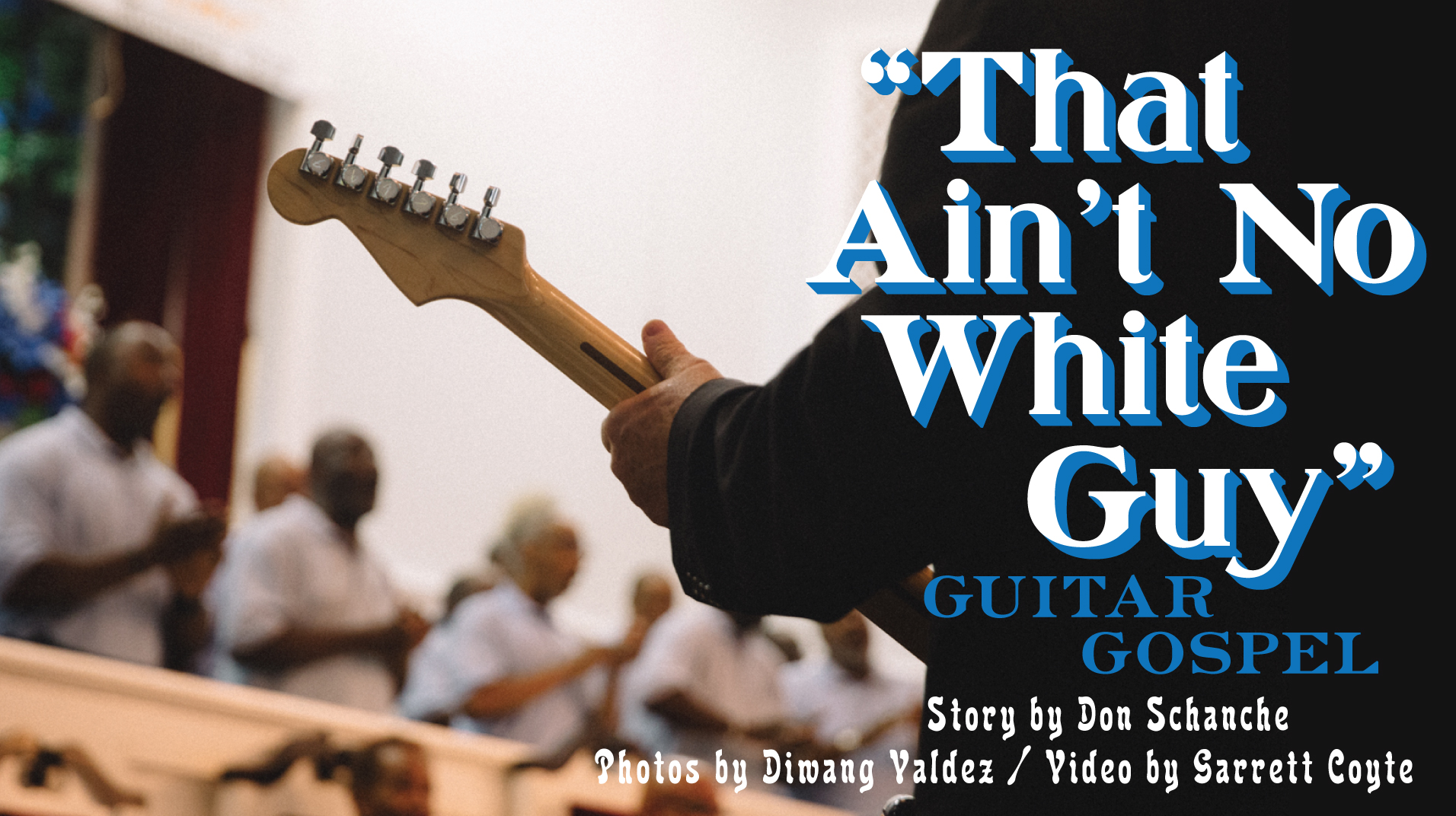

For more than a decade, Don Schanche’s guitar has found him a home in the world of black gospel music, an unlikely place for a middle-aged white guy. Schanche usually delivers a gospel of hope and harmony with a Fender Stratocaster. Today, he delivers it with words (and a joyous video you'll need your headphones for).

Story by Don Schanche | Photos by Diwang Valdez | Video by Garrett Coyte

Drive down I-75/85 to Atlanta’s tattered southside around 4 or 5 o’clock on any Sunday afternoon, exit onto Cleveland Avenue and head east past the title-pawn joints and aging strip malls. Turn toward the neighborhood of modest homes on Brown’s Mill Road, and you reach the red brick Dodd Sterling United Methodist Church, where the parking lot may be jammed with cars and trucks long after the morning church services are over.

If you can find a place to park and walk toward the doors, you hear — or perhaps you feel it first in your blood — pounding drums and a throbbing electric bass, backed by an organ, pianos and electric guitars. As the doors open, you hear the voices: singing, shouting and moaning voices, voices calling for help, calling out praises, calling down blessings, calling on the name of Jesus. Voices joined in harmonies threaded with majors, minors and dominant sevenths all mixed together, the blue notes stirred in liberally, swelling and falling harmonies that run bone-deep, harmonies and rhythms that touch the marrow and remind you what it means to be alive, maybe even make you know beyond a doubt that life is indeed eternal.

Maybe you hear those sounds at the College Park City Auditorium, or Stone Creek Baptist Church in Dry Branch, or Mitchell Chapel African Methodist Episcopal near Sparta, or Mount Zion First Baptist in Smyrna, or Saint Mark Baptist on what people still call Bankhead Highway in Atlanta, or Greater Mount Pleasant Baptist in Tallahassee, Florida, or in a multitude of other churches, auditoriums and storefronts in cities, towns and crossroads throughout the South — programs that kick off at 4 or 5 on a Sunday or Saturday afternoon and might still be going strong, six hours later, with one group after another introduced by the emcee to perform two or three songs, grab the crowd’s attention, stir up some excitement, bring down the house.

You might have learned about the gathering on the radio, from WYZE-1480 AM in Atlanta or Love 103.7 FM out of Irwinton, Georgia, or any of the dwindling number of locally operated stations not yet devoured by the conglomerates where robots have replaced DJs. Stations where preachers still holler and explicate the Book of Revelation and tout transmission shops and soul-food restaurants on signals that drift in and out of range as you cruise down the highway in the night. Where DJs still read the local obituaries and church news and tell you where to find the gospel-music program this weekend. Or maybe you saw a promotional poster stapled to a telephone pole or taped to a shop window on a street inevitably named after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., letting you know what side of town you’re on, because in this color-coded country, the voices you’re hearing are black.

Wherever you find the weekly gospel program, you find songs that have welled up from the depths of a people’s experience, the tunes and lyrics handed down from generation to generation, songs that sound, some of them, just like they might have been sung 100 years ago in a field holler or an a cappella spiritual. Yet, you also hear them rearranged, updated, continually renewed in a musical stream that flows with everything that jazz, blues, rock, R&B and hip-hop have ever expressed.

You hear old-school, rough-edged, funky stuff alongside streamlined crooning from groups with names like the Gospel Creators, Tiny and the Saints, Together as One, the Gospel Ambassadors, the Emoni Gospel Singers, the Bonnettes, the Heavenly Voices, the Gospel Originals, the Love of Faith Gospel Singers, the Anointed Ones, the Sensational Jubilees, the Gospelairs, the Golden Stars, the New Gospel Travelettes and the Mighty Zion Trumpets. Quartets, soloists, musicians and choirs, they come together somewhere every week, often traveling long distances to sing, eat fried fish and collard greens, swap greetings and family news, and show off a new musical lick and a sharp new suit of clothes.

These aren’t the nationally known gospel groups that tour in sleek buses, play to big crowds and charge $25 a ticket. These are the locals, people who mostly don’t get a second glance from the world — many of them truck drivers, nursing assistants, janitors, cooks, domestic servants and construction workers — yet they are renowned where they live as makers of holy music.

And for past 10 years or so, at any of those places you might have seen among the black musicians behind the singers a paunchy, bearded, red-faced white man of middle years, playing a midnight-blue Fender Stratocaster with his eyes closed, likely drenched in sweat, lost in the music. If you saw such a man, I can say with a fair degree of certainty, the man you saw was me. I’m not out front, not a star. I lay down some bluesy riffs and some R&B, interspersing rhythm with lead runs, finding a place among the instruments, complementing the voices, supporting the total sound.

Over the years I’ve played guitar for Emoni, the Voices of Calvary and the Love of Faith, and I’ve pitched in for a bunch of other groups, preachers and deacon boards that needed a guitar player to accompany them, open a service with a devotional song or just play a tune while they take up the collection. I’ve played in little storefront churches and with the opening acts for big stars in front of large crowds. It still surprises me to find I’m wearing the only white face in this room full of soul. Sometimes, a few pale spectators pop up in the congregation, but in the decade I’ve been doing this I’ve never run across another white musician at a program. I’ve heard of a few, and I’ve met one or two who used to play gospel — but clearly there aren’t many of us.

While there’s nothing new about black and white musicians playing together, from Manhattan to Memphis to Muscle Shoals, it doesn’t seem to happen much in church.

Sometimes I laugh and feel like pinching myself to think I get to do this.

It began for me in the mid-1990s, when I was an editor at The Union-Recorder newspaper in Milledgeville, Georgia. I had gone to interview gospel singer James Manson, a veteran of the circuit, who some locals called “the Godfather of Gospel.” James had a studio in his garage where he made recordings with one of his groups, the Voices of Faith. Inside the converted corner of his ranch-style house, a few blocks west of downtown Milledgeville, I asked him some questions and then listened to him and the group rehearse.

I’ve played guitar since I was a teenager. I played in a few bands, none of which ever got beyond the local Holiday Inn and some that seldom emerged from the drummer’s basement. Mostly I played rock, blues and oldies, and for a while I was in a country band that played at parties and honky-tonks. The magic of making music grabbed hold of me as a kid and never let me go. And I’m not bad at it, at least when it comes to the blues — and blues, as any listening ear can tell, is half-sister to gospel.

So finally, after interviewing James for a while, I couldn’t help myself.

“I play a little guitar,” I said.

“Oh, yeah?” he said, eyebrows raised. “Why don’t you play some?”

Which sounded to me like, “Prove it.”

Troy Barnes handed me his guitar — I believe it was a Peavey copy of a Fender Strat — and I picked some blues. James’ son fell in on bass, the drummer joined us, and we went through a few rounds of a slow, 12-bar blues. I threw in some lead runs, just for fun.

James smiled.

“Yeah, you can play,” he finally said. He called what I was doing “old-school.” After a pause, he asked me to play with his other group, the Piney Groves, at a gospel program coming up in a few weeks.

“Why don’t you tune up with us?” was the way he put it.

So, I did.

The gospel show starred groups from around middle Georgia — guys with matching suits and tight harmonies, and women dressed in bright colors, with elaborate swooping, wavy hairstyles, like sweet swirls of icing on a chocolate cake. They packed the auditorium at Georgia College in Milledgeville. I had listened to the Piney Groves album on cassette tape to get ready for the concert, and thought I had their songs down pretty well — but onstage, I discovered something I would learn again and again playing gospel: The band didn’t do it live the way they did it on the record.

After a panicked moment, I caught on to the difference in rhythm and key, and I mostly kept up — even threw in a solo when James gave me a nod. Afterward, I was pretty sure I had frozen and flubbed it, but I got some good reviews. James didn’t invite me to join his band — he already had Troy, one of the finest gospel guitarists I’ve ever heard. But a few years later, I did get an invitation to join the Emoni Gospel Singers — Emoni, from the Swahili word for faith, usually written in English as Imani. The group is based in Milledgeville, led by Curt Davis, who worked for years at the state hospital there and played R&B back in the 1960s. His wife, Lillie, is the lead singer.

Curt told me later that after he and Lillie heard me play, they talked about needing a guitar player, and he told her, “Just call him.” When she did, of course, I said yes.

I recently asked them to recall what it was like, having a white guy join the group.

“You don’t find many white guys playing gospel music,” Lillie said. I asked Curt what the congregation and the members of the other groups thought about it. He chuckled.

“Hey man, they said you play like a black guy,” he said. Then, laughing even harder and making me laugh too, he added, “They said, ‘That joker ain’t white, that joker’s black.’ They said, ‘Oh no, he musta got painted.’”

In the years that followed, I played regularly with Emoni, traveling all over southern and central Georgia in Curt’s van to little churches in Fort Valley, Hawkinsville, Dublin, Linton, Hinesville, Dry Branch and as far as Cuthbert, south of Columbus near the Alabama line, where we played at a memorial for Lena Baker, a sharecropper who was executed in 1945 for killing a farmer who abused her, the only woman ever sent to Georgia’s electric chair. We played at big churches in Milledgeville and Savannah — and we opened for gospel star Lee Williams at the magnificent Macon City Auditorium, a cavernous domed space filled with thousands of people, where Little Richard performed as a child and promoted gospel shows while he was still a teenager, where James Brown played on the Chitlin’ Circuit and where they held Otis Redding’s funeral in 1967. One time we even flew to California, where a promoter put us on gospel programs in Los Angeles and San Diego. I still have photos of Emoni standing in front of the welcome sign for Beverly Hills.

I learned how to find the key when a singer jumps into a song without warning, how to feel the changes in a tune I’ve never played before and get the hang of it onstage by the second verse. I learned where in Macon and Atlanta to find the little clothing shops still run by Middle Eastern immigrants who could sell me a sharp suit to match what the rest of the band was wearing. Not an expensive suit — but sharp. A band might spend as much time discussing what to wear as it does rehearsing music. I was walking around after a Macon performance one night when I ran into a black Milledgeville city councilman whom I’d known for years. Looking me up and down, he took stock of my white suit, purple shirt and purple shoes and asked, “Don, who taught you to dress like a brother?”

“The Emoni Gospel Singers,” I answered.

I have a gold suit, a white suit, a black suit, a brown-and-gold pinstriped suit, and even one that’s supposed to be peach-colored. In fact, it’s more of a Creamsicle hue, and I’m here to testify that a red-faced white man does not wear Creamsicle as well as a cool black brother. But I don’t care: I am in the number! I am part of the sound.

Hanging on by a guitar string, I’m an accompanist for the voices of Heaven.

In little country churches where the rest of the world will likely never discover them, I’ve heard musicians who astonish me — natural-born geniuses like Leconar “Junior” Brown who played drums for Emoni and went on to form his own band, Out of Darkness, with Troy, the guitarist who played for James Manson. And another Emoni guitarist, Carlos Toombs, whose music is absolutely free and fearless, full of joy, the essence of child’s play. And Derran Ford from Macon, who says little but does things with chord voicings on the guitar that fill me with wonder, leave me baffled and perplexed. Guitarists whose names I never learned, whose fingers embody pure dance, running effortlessly in and out of the melody, weaving grace notes around the singers’ words — and who maybe even sing while doing all that on the guitar.

They’ve been playing in church, some of them, since they were barely old enough to creep up beside the organ player and place a finger on the keyboard, or to tug on the drummer’s sleeve and shyly ask to take a turn. By the time such a child is a teenager, he or she has likely mastered all the instruments and maybe even plays them in new and strange ways that older musicians try to emulate.

I never used to understand what people like Aretha Franklin and Whitney Houston meant when they told interviewers they developed their sound by singing in church. White kids raised in my suburban New York hometown heard solemn, dirge-like church hymns if they went to church at all. Sometimes stirring, but seldom exciting. And if there was a teenage choir, the kids were usually dispirited and embarrassed. Now, I understand a little better what those R&B divas were talking about, after taking part in rehearsals where infants and toddlers accompany their mothers, aunties and grandmothers, absorbing the sounds of soul before they can even sing the words. To feel yourself pulled irresistibly to your feet during a Pentecostal service in full musical swing is to know immediately you are at the source of all blues and jazz and rock and rap — all of it — and to understand that the source still flows down through the generations like a mighty stream.

And every Sunday I get to make music with singers who stir the soul like Aretha and Otis — and yet they’re not singing like Aretha Franklin and Otis Redding. The truth is, when Aretha and Otis exploded onto America’s stage, they sang like they were in church. Church just keeps escaping into the nightclubs and infiltrating the wide world.

I kept on playing with Emoni even after I moved to Atlanta a few years later to get a job with a news wire service. But after a while, the 200-mile round trips for rehearsals wore me down. So did the weekend treks to places so out-of-the-way they stretched the capacity of any GPS unit. So gradually I quit making those trips — but then some Atlanta groups took me in.

The Love of Faith had been on the Los Angeles trip with Emoni — Liz Bullard, Frank Askins and Nita Wilson, a square-jawed woman with fire in her eyes and the voice of an avenging angel. I became their regular guitar player for a few years. We played all over south and west Atlanta, but most often at Dodd Sterling, where the Rev. Robert Melson and his congregation don’t mind letting gospel groups use the sanctuary in the afternoon, and at Streams of Living Water, a tiny house-church on West Lake Avenue. I even introduced Love of Faith to Atlanta’s Friends of Folk Music society, and to my old church in Milledgeville, First Presbyterian, where the Love of Faith and Emoni together shook the rafters one afternoon with lyrics John Calvin might have approved but sounds he never dreamed of.

Then, one day the day the phone rang, and a deep bass voice said, “Don, this is Howard Calhoun of the Voices of Calvary.” I had heard them sing before, a group of men in their 60s and 70s, with old-school harmony that made my hair stand up. Their lead singer — a bald, blind man named Squire Reed — was also a rapper, chanting rhythmic lines about how Jesus would straighten it out. He electrified the place. Howard invited me to join, and I played with them, off and on, for a few years, until Howard grew too ill. When he passed away last year, I played in the band at his funeral.

For a couple of years I played every Sunday at Holy Temple Deliverance Church in East Atlanta, where Bishop Nelson Clements preached impassioned sermons that reached long, chanting, musical crescendos while the church band jammed hard behind him for 10, 15, 20 minutes at a stretch, as congregants danced, shouted, spoke in tongues and sometimes fell out on the floor. It was a weekly catharsis, a loosening of burdens, a visitation of mystery and awe. For a musician, to evoke such a response means more than you can put into words. They treated me kindly at Holy Temple, but eventually it felt like time to move on — and so I did, to a place just around the corner.

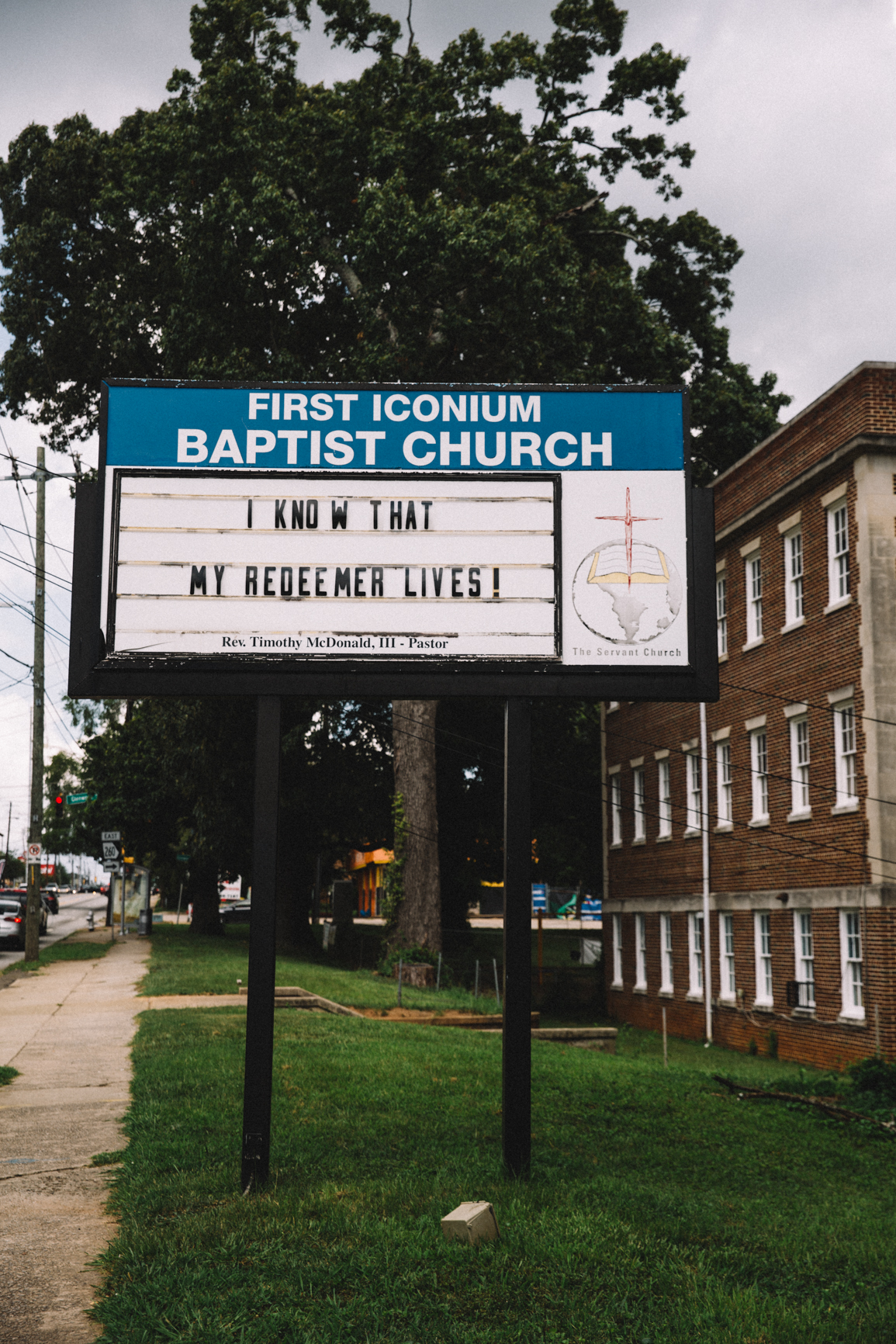

Most Sunday mornings these days, you can find me playing in the church band at First Iconium Baptist on Moreland Avenue in East Atlanta, a couple of blocks south of I-20. The place is widely known, even outside church circles. You can Google it — whenever there’s a protest on behalf of poor people in Atlanta, you’re likely to see my pastor, the Rev. Timothy McDonald, carrying a bullhorn and joining in. Sometimes he gets locked up for his efforts. Lately he’s been speaking on behalf of immigrants, and he helped lead efforts to block a so-called Religious Freedom bill that would legally authorize businesses to deny services to gays and lesbians. Week-in, week-out, he preaches a message much in line with that of the Rev. Martin Luther King: inclusion for the marginalized, advocacy for the powerless, speaking truth to power. There aren’t many preachers like him, black, white or otherwise. Plus, the musicians are dynamite. Right now, there’s a 16-year-old kid named Avery Dixon at First Iconium who plays the alto saxophone with the soul of a 40-year-old jazz master. He’s already made three trips to perform at the Apollo Theatre in Harlem, and he’s just getting started. Remember his name: I believe you’ll hear it again.

To me, it means everything to be part of this gospel sound. To my fellow musicians, though, and to the pastors and the people, it doesn’t seem to be a huge deal to have a white member in the band.

Sometimes a visitor looks over in the musicians’ corner and asks, “Who’s that white guy on guitar?” My pastor tells me he replies, deadpan, “That ain’t no white guy; that’s just Don.”

But occasionally, someone points out the incongruity. A man about my age once came up to me after a gospel program and, without a word, grabbed my hand and held it next to his own — my hand pale pink, his the color of dark coffee. Wordlessly, he shook his head and smiled — and together we silently considered how we could look so unalike, yet resonate so deeply together.

I find it the coolest thing in the world to play gospel music, to be the white guy in a really tight black band, playing our hearts out, locked into a drive, deep in the pocket, tight like a ball bearing rolling around the polished steel shaft of a high-speed motor, getting a chance every week to back up singers who make pure soul music. And when I tell my friends what I do, they often agree it’s cool — sort of. Except that … well, it’s church. Most people I know, white and black, have bad memories of church hypocrisy, church prejudice, church money-grubbing. And even if they can put those aside, there’s Jesus, who confounds people on multiple levels. Besides all that, a lot of my friends believe in something else entirely, or simply don’t believe at all.

Here, I should mention something that should not go without saying, namely that I profess to be a Christian, a follower of Jesus. To say that is to risk being misunderstood, especially when what it means to be a Christian takes on ugly political overtones in this country. And my own understanding of what it means has shifted over the years. Suffice it to say I depend daily on someone who said the most important things in life are to love God and to love one another.

I didn’t always. As a teen, I couldn’t imagine why any thinking person could believe in God. So it took me by surprise one day while away at college, my mind coming undone after months of enthusiastic cannabis ingestion, to find myself kneeling beside my bed, asking God for help. Somehow that help came, the turmoil subsided, and I began to know that God is real. It took me a while — years, in fact — to admit out loud that I believed in God and that I specifically believed in Jesus. But I do.

So stepping across the church threshold wasn’t strange to me. I’ve been doing it all my adult life. But stepping into black churches meant stepping across the color line, a fraught decision for anyone of any color in this country.

What right did I have as a white American, heir and beneficiary of white privilege and all its advantages, to insert myself into the ultimate For Us, By Us experience of Black America – the black church? Well, none – none at all. I’ve lived a privileged life, never wanted for much of anything. My Norwegian and English forebears weren’t mistreated that I know of, and I have never experienced what it means to be a black man in this country or felt a black man’s apprehension when blue lights appear behind his car, knowing that he could in the very next moment be convicted and executed on the street for the offense of being African-American. Not to mention that white musicians have been stealing black music ever since black people in chains, strangers in a strange land, first raised songs of grief. For me to stand up in a black church, as if I had any right – what gall! As a white musician friend responded when I invited him to church one day, “Won’t they be mad at me?”

Not long after I began attending First Iconium, but before I started playing music there, one of the assistant pastors, the Rev. Heshimu J.D. Sparks, delivered a dramatic monologue from the pulpit. A tough-looking man with a shaven head and a bulldog’s visage, he spoke forthrightly about the suffering of black men over time and the bitter pain of knowing that the blood of slave masters who violated the enslaved women flowed in his veins. Speaking extemporaneously as he left the pulpit and began walking up the aisle, he detailed the abuses of history, the crimes against the oppressed. And as he walked, he spoke too of the love of God that made him lay that anger at the cross, made him willing to forgive. And just as he reached me, sitting at the aisle end of the pew, he grabbed my hand and said God’s love allowed him to call me “Brother.”

I was blown away — absolutely blown away. And I knew I wanted to return to that church.

J.D. recently told me that he was indeed once filled with rage at white America — similar to the rage of his Alabama-born father, who had seen his favorite uncle lynched in the early 1900s. But eventually, J.D. said, he did indeed lay that anger down.

“I’m not one of those guys who likes to say there shouldn’t be a white church and a black church, because I think that’s inevitable,” he told me. “However, having said that, I don’t think it’s a big deal in your case with First Iconium, because you’re playing gospel music. And I think that has to do with the fact that you’re such a soulful guitarist in the first place.

“And being soulful with your guitar doesn’t necessarily mean being black,” he added. “I just think you’re a soulful musician. Even though we may come from two different cultures that worship differently, by and large, I think the fact that we can still come together and worship is the most important thing.”

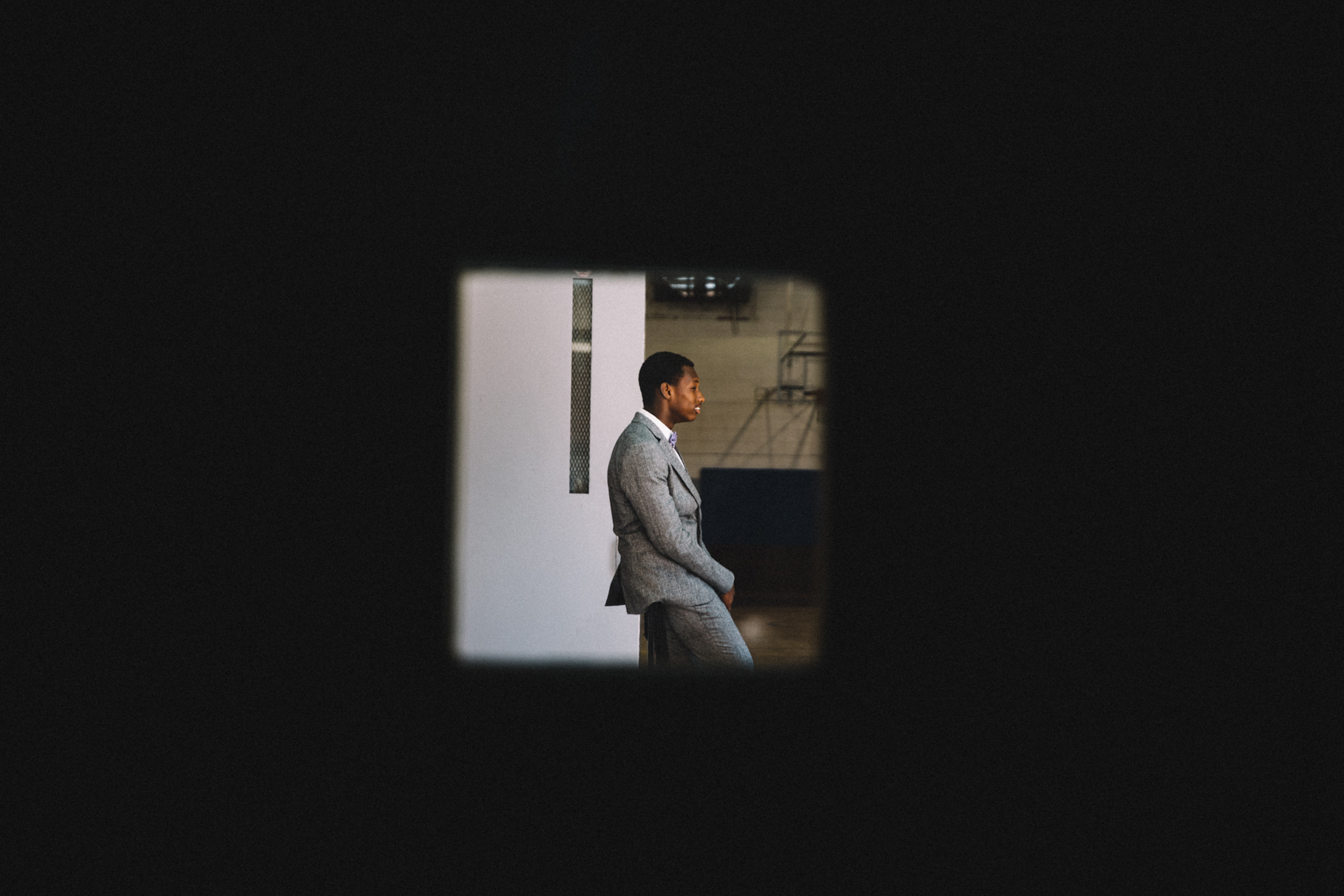

REV. TIMOTHY MCDONALD, III

Rev. Timothy McDonald, III

I asked Rev. McDonald, too, how he feels about having a white guitar player — and I wasn’t surprised to hear him say it’s not a big deal to him. But he also told me a story about something that happened to him in the 11th grade. He went to a newly integrated high school in Brunswick, Georgia, in 1971, and the school chorus was invited to First Baptist Church to sing. But when the deacons found out the soloist would be Tim McDonald, he said, “They disinvited us.”

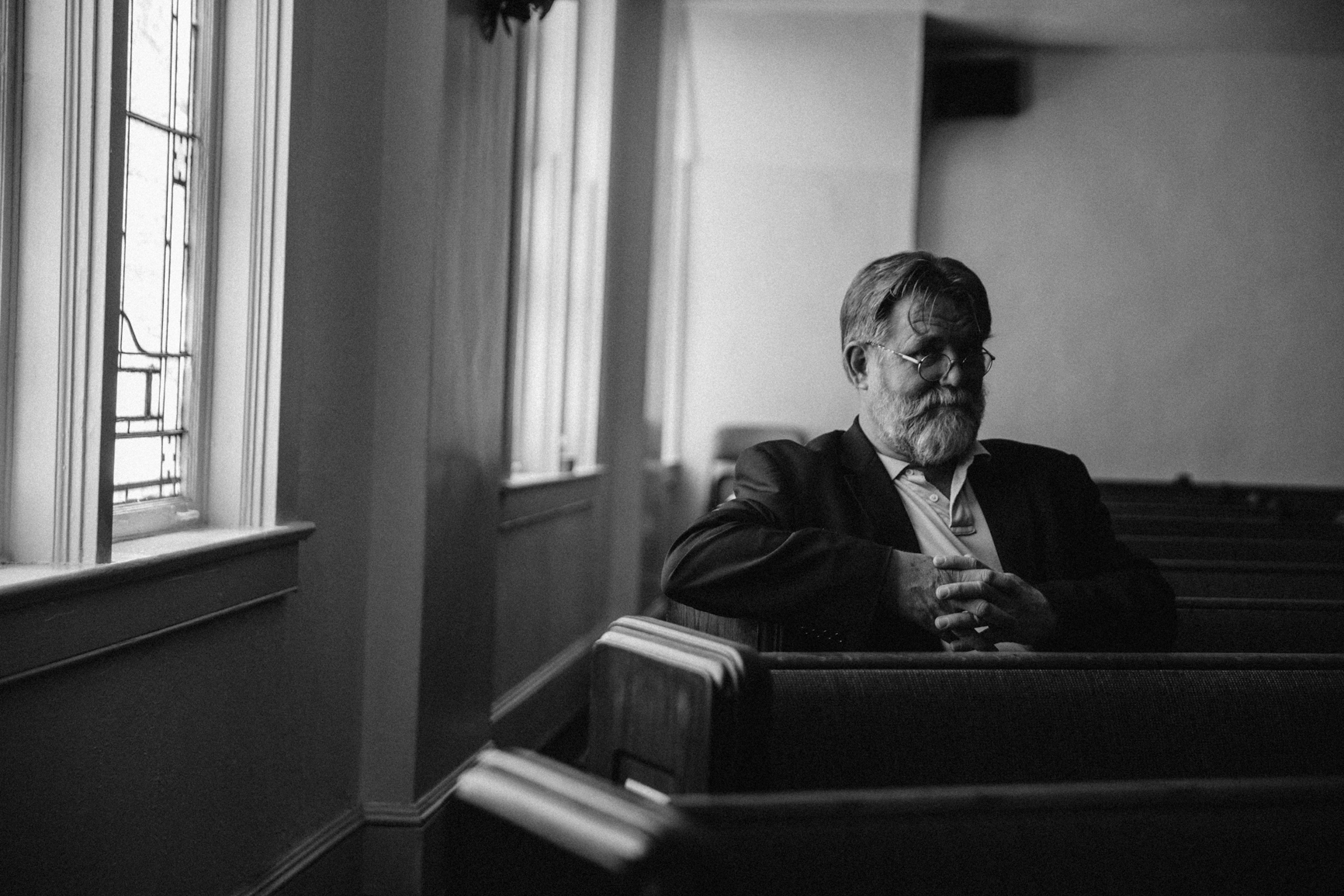

DON SCHANCHE

“And I’ve always admired the pastor,” he continued. “Because he said, ‘As long as I’m the pastor here, they’re going to be allowed to sing.’ His church split. They voted him out. He started another church, but about half the people went with him…

“I think that had something to do with how I perceive you as well,” he added. “I said, ‘Because I had the experience, I will never do that to anybody, particularly a white person. If you want to come and be a part of us, you’re welcome.’”

Along with his willingness and the willingness of others to be inclusive, there’s also a way that believing in Jesus helps me. As I read the Scriptures, no one has a “right” to join Jesus’ church — not one of us sinners, black or white, rich or poor, young or old. We can enter only because he invites us, all of us. And as I thank God for saying yes, I thank my black brothers and sisters for not saying no. Only once in all these years has a pastor ever asked me, “Don’t you have your own church to go to?” — as I imagine she or someone she loved was asked that same question at some other time, in a church with some other color scheme.

Ever since I worked for the newspapers in Milledgeville and Macon, where blacks and whites lived in one place but two worlds, together but apart, an idea began to form in my mind: Before I die, I want to be able look around and speak the truth when I say, “We are one community.” I want it even more today, when insurgent cellphone video forces us to confront the racism and brutality woven into our heritage.

That requires some crossings of the color line, some steps large and others small. It’s still true today, by and large, what Martin Luther King said: 11 o’clock on Sunday morning is the most segregated hour in America. But in my own personal crossing on a Sunday morning or afternoon, for a while anyway, my little dream seems real.

And the music – it comes from a place where the soul never dies.