You Can Make It There

In Florence, Alabama, a homegrown fashion line is filling the holes left by the town’s defunct T-shirt industry — and retooling the way clothes are made, from farm to label. As the South grapples with hard truths about its former glory as a textile mecca, Alabama Chanin draws a new blueprint for building careers around community.

In the opening scene of the 2013 documentary film, “Muscle Shoals,” Tom Hendrix stands in front of the mile-long natural monument he built beside the Tennessee River in memory of his great-great-grandmother, who was a member of the Native American Yuchi tribe that occupied the area in the 1800s. Hendrix named his creation the Wichahpi Commemorative Stone Wall, but Alabamian artists and musicians like to call it the Magic Wall, because — legend has it — when one stands next to the wall, the river sings.

The mystical vibe captured in this movie scene existed in Alabama long before the middle of the 20th century, when Sun Records founder Sam Phillips deejayed on WLAY-AM, Percy Sledge left his job as a hospital orderly to become a soul singer and Rick Hall opened the world-renowned Fame recording studios. Artists in the Quad Cities of Muscle Shoals, Tuscumbia, Sheffield and Florence — all along the river — suppose it’s something in the water that spins a musical thread through their flourishing creative communities.

A bit of this magic rubbed off on designer Natalie Chanin, a native of Florence who got a huge boost in her career when she was nominated for the Council of Fashion Designers of America / Vogue Fashion Fund in 2009 after creating a clothing collection influenced by the strong, feminine styles of Alabama-native country singers Emmylou Harris and Allison Moorer.

Chanin, a textile artist and pioneer of organic cotton couture, worked for two decades as a juniors sportswear designer in New York and as a stylist for music videos and advertisements in Europe before moving back to her hometown of Florence to start Alabama Chanin in 2006.

Chanin’s designs, sewn by local artisans and reflective of the flora and fauna of Florence, began to attract the attention of the singers she admired. With her shock of white hair, dark eyes and wide smile, Chanin looked like a bit like a rock star herself (although, like the songwriter Sia, she doesn’t enjoy being photographed), but she didn’t know she had a fan in Rosanne Cash until the two met through a mutual friend and realized they embraced their Southern heritage in similar ways.

It’s not often that a Grammy-winning singer uses a fashion designer as her muse for lyrics, but Cash did when she and her husband John Leventhal wrote “A Feather’s Not a Bird.” The song captured a 2013 pilgrimage to her father Johnny Cash’s boyhood home in Arkansas and road trips down the Natchez Trace in Alabama, where she spent time sightseeing and sewing with Chanin.

“I’m going down to Florence, gonna wear a pretty dress,” Cash sings on the recording. “I’ll sit atop the Magic Wall with the voices in my head.” Partly in homage her trip to the region, she named her 2014 album, “The River & the Thread.” In February 2015 at the Staples Center in Los Angeles, Rosanne Cash accepted three Grammy awards for the album while wearing an Alabama Chanin coat. Of her inspired trip to Florence, Cash remembers: “The whole time, I was thinking about what Natalie said: ‘You have to love the thread.’”

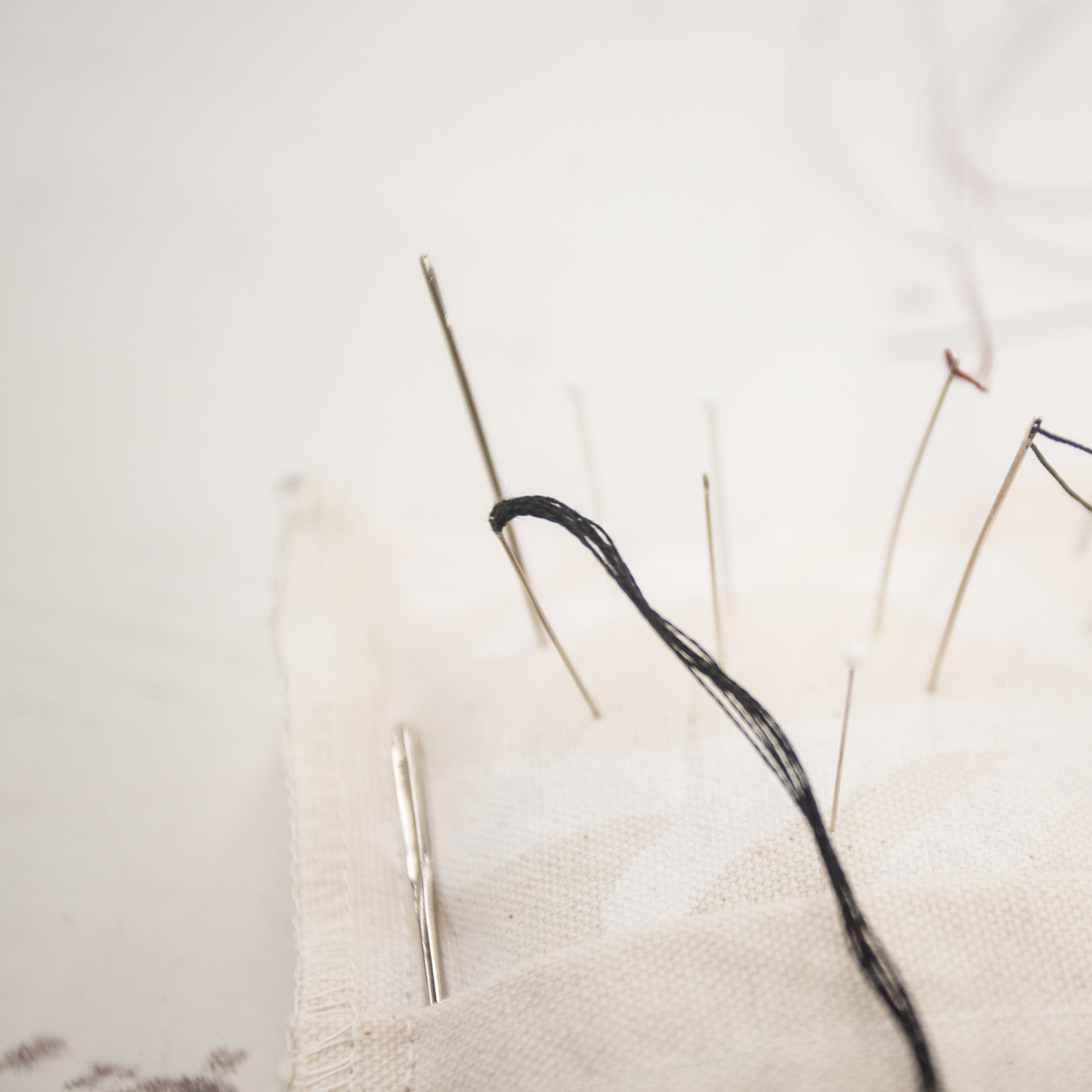

For most of us, thread is something we think about only when it breaks — a lost shirt button, a ripped hem, a dangling end waiting to be trimmed. But for Natalie Chanin, thread is the tie that binds her to Southern textiles and to the relatives who worked at Florence’s Sweetwater Mill during the industry’s heyday. Chanin’s designs reflect this connection to the past and are dominated by visible loose threads, exposed stitching and knots; to see, touch and wear these clothes is to believe in the omnipresence of the figurative and literal threads in each of our lives.

When Cash wrote about Chanin “loving the thread,” she referred to a process wherein the sewer runs the thread between her fingers as oils from the skin smooth the fibers to keep them from fraying. For Chanin, this love of the thread is a larger metaphor, a therapeutic process that teaches lessons about being stewards of the environment and the land — and about caring as much about the fabric we put next to our bodies as we do the food we put in our mouths. Her philosophies about thread extend into her recent business expansions, which include not only the Alabama Chanin clothing line, but also housewares, a café and The School of Making, through which Chanin and her employees educate and share the company’s ideas at curated events.

This past June, I attended an Alabama Chanin do-it-yourself women’s sewing seminar at the Blackberry Farm resort in eastern Tennessee. There, on a rainy Saturday morning, Chanin held forth in front of a dozen women about the power of thread. Each attendee had purchased a kit with organic cotton jersey fabrics, needles and beads, and was eager to attempt the assembly of her own hand-sewn garment. Like music fans wear band T-shirts to rock concerts, many of the women were dressed in Alabama Chanin-made clothes.

“You need a family of stitches to support the fabric,” Chanin said, while holding up a sample seam in one hand and assisting a lady on a floral appliqué with the other. As one woman re-threaded a needle, Chanin reminded her that the “thread should never be longer than the distance between your finger and your elbow. That way it will be perfectly matched to your natural machine.”

The two-day affair contained its share of folksy banter, peppered with statistics that compared the new manufacturing world order with the old: “During an average production run, Building 14 [Chanin’s factory in Florence] can produce around 120 garments a day vs. the 120,000 dozen that were manufactured a day by Tee Jays, the company that once occupied the space,” Chanin told us. She also equated the 21st-century slow food movement with the sustainable textiles trend (the Southern Foodways Alliance is a key Alabama Chanin partner for events and projects) and provided her opinions about NAFTA (the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement that many believe sounded the death knell for American textile manufacturing). Chanin drew from her academic experience, throwing in ideas about color as espoused by Josef and Anni Albers (the Bauhaus artists who fled Nazi Germany for Asheville, North Carolina, in 1933 to teach at Black Mountain College) as well as her own vast knowledge of fabric sources gained from classes she took while earning her degree in environmental design from North Carolina State University.

Chanin’s company’s “zero waste” mission is to “preserve traditions of community, design, producing and living arts by examining work and life through the act of storytelling, photography, education and making.” While the cost of the finished garments in her store may be prohibitive to many, the items of clothing are sewn primarily by women who might otherwise have access only to sporadic work or no other income at all: single mothers, women physically unable to work in a traditional setting for eight hours per day and parents of small children who desire supplemental earnings.

The pricing of finished garments is not scaled specifically to cater to the wealthy or profit from the sustainability crusade; it is merely an honest statement about the realities of our material world and the value of quality handiwork and sweatshop-free clothing manufacturing. For example: depending upon the amount of embroidery detail, a ready-to-wear, hand-embroidered Alabama Chanin sleeveless A-line tunic created by an artisan could retail for up to approximately $2,210 (or more) in a store or online, vs. one of the company’s DIY kits, which contains cut pieces for the buyer to sew and embellish and can be purchased on the Alabama Chanin site for around $248. (While working on this story, I connected with April Morgan, a long-time sewer for Alabama Chanin, who believes the company’s flexibility “put a lot of bread on my family's table” and gave her the opportunity to raise two daughters while working from home and watching them grow up. “I wish this for every working mom,” she said.)

It was an ambitious, deeply moving weekend at Blackberry Farm. Our sewing sessions were punctuated by gourmet snacks and meals prepared from local ingredients by award-winning chefs. I embellished about 10 of the three-dozen flowers on the front panel of my floor-length dress from the kit, and was so deep into my sewing that it took me an entire day of small talk to realize that the gal next to me has a son who attends the same Atlanta school as my child. There we were, sharing stories hundreds of miles from home in a beautiful setting, and yet we’d never met in the carpool line after years together at the same school. I thought about the irony of our privilege. Even the poorest of our great-grandparents’ generation had a certain level of access to natural materials and the relative luxury of time to transform them into something functional, valuable and beautiful; today, fewer people can afford such opportunity. The workshop was more than just a craft project. It became an emotional and philosophical lesson in gratitude for the vision of artists and makers whose work is helping rid the system of ways that are harmful to the earth, to economies and communities.

After witnessing how the Alabama Chanin products are put together, it is impossible to not think about the origin and status of every piece of clothing in your closet. To maintain our American lifestyles and afford abundance at low prices, we turn a blind eye to human rights violations, low wages, land stripping, toxic chemicals and other offenses of textile manufacturing that occur internationally and sometimes even on U.S. soil.

Alabama Chanin, the brand, might have international cachet, thanks to its high-profile fans, but it’s a small business compared to Northwest Alabama’s primary economic generators. Aluminum sheeting for soda cans and automotive light fixtures are the products made by the region’s two largest manufacturing employers; companies in the textile industry no longer make the top 25, in spite of their crucial role in the cultural identity of the Shoals area. Chanin has 31 employees and is currently working with 21 independent artisans.

Natalie Chanin and fellow Florence designer Billy Reid collaborated on a local cotton-growing project in 2012 that proved successful but not financially viable to continue full-time. The pair and a team of around 300 collaborators, friends and family were able to produce seven acres of organic cotton to hand-harvest, process and use for a limited-edition run of T-shirts and scarves. It was a two-year process Chanin characterized as “an experiment” that might lead to future cotton growing endeavors. For now, Alabama Chanin sources organic cotton, from seed to shelf, from U.S. companies. This approach is a challenge that requires extensive forethought, energy and planning.

“At our production studios, we cut all of our garments. Our machine-made garments are sewn in-house. The hand-sewn garments are made out-of-house by our artisans. We do not do any spinning, knitting (or weaving) here. We have a small natural dye house where we dye fabric by hand with organic indigo. All other colors are dyed at a facility in Raleigh, North Carolina.”

She says the company uses other Southern suppliers, such as Green Textiles in Spartanburg, South Carolina, and works primarily with a cotton jersey fabric that is “grown-to-sewn” in America, with raw cotton sourced from Texas; Chanin also uses a fabric loomed with imported organic yarn that comes from Turkey and/or India, “because there are no longer any machines left in the USA to spin that finer-weight yarn,” she explains. The slow-fashion textile industry may not be the biggest employer, but it is surely the least ageist: Experts who worked in the textile boom more than 30 years ago are now in big demand to run machines and train younger employees.

The task of transforming cotton back into its God-given purpose of comfort and strength doesn’t fall squarely on the shoulders of fashion designers like Chanin, who seek to keep their businesses in the Southeastern U.S.. Yet, any good Southerner’s role in changing the current system will involve not only the rebranding of cotton — and a reclaiming of the fiber’s lightness and worth — but also an insistence that the process be inclusive.

The trade organization Cotton Inc., founded in Cary, North Carolina in 1970 to boost U.S. cotton sales, made a grand (and unforgettably tuneful) attempt at refurbishing cotton’s rep in the 1990s ad campaign, “The Fabric of Our Lives.” C.I. is credited with driving the increase of cotton’s share from 34 percent of the polyester-dominated 1975 fabric market to more than 60 percent in 1983. However, the award-winning ad campaigns it has produced over the years have never acknowledged the dark history of the industry.

In comparison to conflict diamonds, oil and other natural resources rife with political pain, cotton may be the damned heaviest. Until Americans — and particularly Southerners — own up to the fact that slavery aided America’s “Cotton Economy” 200 years ago and ultimately gave rise to the South’s dominance in textile manufacturing in the mid-20th century, cotton will never be lily-white — not as a commodity, as a cash crop or as a fashion staple. The reparations for cotton’s sins won’t come from media stunts, but from the unsung makers who risk their livelihoods to take cotton from seed to shelf with integrity.

Chanin has a project in the works that may provide insights into the “complexion” of the 21st century Southern textile worker: She wants to know why job applicants in the new textile movement don’t represent the diversity of their local communities, particularly in Alabama. In conjunction with scholars at the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi, Alabama Chanin plans to lead a 2016 study that will serve as an oral history of sewing in the region — collecting data on both personal and professional uses, including quilting, mending, machine work and factory experience. The Center’s director, Ted Ownby, says the study is one of many ways Natalie Chanin is “cultivating a community of people who wish to find new ways to think about old things.” Chanin hopes the study will ultimately drive outreach for job training and skill development to fill factory jobs in Florence with a diverse workforce and provide viable textile job opportunities to underrepresented segments of the population.

Two months after the Blackberry Farm experience, I drove from Atlanta to Eva, Alabama, to pick up my cousin before heading to Florence to visit the Alabama Chanin factory. We set off on two-lane roads listening to Florence songwriter Donnie Fritts sing a cover of the ballad “Errol Flynn” on Spotify. At one point, we were so far out in the country there was no place to use the restroom for nearly 25 miles. We stopped at a gas station to enquire about facilities, only to be told to head eight more miles up the road.

We arrive at the industrial park outside Florence a little after 9 a.m. and are greeted by a cadre of pleasant millennials dressed in Alabama Chanin pieces. These employees have anticipated our arrival, and give us a tour of the café and showroom, where Chanin’s designs are previewed to visitors. The new looks favor bright blues and camels in bold geometric shapes — a change from the swooping botanicals in black and burgundy that have become Chanin’s signature feature. There’s a music and fashion festival called the Shindig (hosted by Reid) happening in Florence for the weekend and the shop is already teeming with out-of-towners at this early hour.

Our guided tour of the factory includes glimpses of pattern making, indigo dyeing, cutting for the kits and a machine-sewing unit that puts together the less-expensive “A. Chanin” line of basics. Stacks of the jersey are neatly stacked and categorized by colorway, and an enormous pile of scrap material sits in a bin in the corner, with an old-fashioned scale for those who wish to purchase the remnants by the pound for DIY embellishments or for smaller projects such as scarves.

Aesthetically, the factory rooms are white, bright and clean — the whole place feels comfy and eternally ready for a photo shoot. I imagine the bustle of workers producing nearly 1.5 million shirts decades ago in this serene space, long before Chanin repurposed the building and added skylights. The curation behind the factory experience is deliberate and purposeful; how else should a company proselytize the benefits of a simple organic lifestyle?

I meet Natalie in her office for an interview, where she talked about her life as a single mom, her education, her travels and why she now lives and works in Florence. As she spoke, it became obvious why her company bears both her name and the flavor of her personality: There are few business ecosystems like Alabama Chanin’s, with its community-centric model, reverence for the textile industry’s past and respect for the future of Southern culture. I wanted to know why Natalie left Alabama, how she came back to her home state to start her company, why she cares where her cotton comes from and what she thinks is so special about the South. In her own words — and soft accent — it all made sense:

Leaving Alabama

“I remember being kind of embarrassed that I was from Alabama. I moved to Chattanooga when I was in the 10th grade with my mother. That seemed like a really good city, so I always told everybody I was from Chattanooga and never talked about Alabama. You know you’re from the country when Chattanooga is metropolitan. It took me time to really appreciate [being from Florence]. Not that I didn’t love Southern literature and stories of the South — I did. But for Southerners, there’s a heaviness in our past that we have to that we carry with us everywhere we go. ”

Cotton Talk

“Anytime you talk about cotton, it’s so rife with controversy, it doesn’t matter what you say. Any way you say it, you’re always the bad guy. There’s no way to heal a scar like that. You can’t. There’s no plastic surgery that’s going to make that scar go away … but I want to be a part of the solution if there is a solution.”

Swapping the South for New York

“After I graduated from college, I really thought that I was going to be working in North Carolina. It was a while before NAFTA really took hold and the industry really came to a screeching halt, but by ’87 and ’88 things were already starting to change. I couldn’t find a job. This friend of mine had moved to New York. I wound up sending out some resumes, and at the end of the week I had a job in New York City. It just seemed like every door I tried to open in the South, there was no place for me to land. Suddenly I had this job in New York, and it felt kind of like I was cheating on the South.”

Sewing and Food

“My grandmother sewed every dress that her girls wore — even when I was from 8 to 18, she made everybody’s underwear, nightgowns, everything. She made all my dresses as a little girl and then my other grandmother was the same. There was always a sewing machine. Back then, people said they didn’t work, but they worked all the time to make a beautiful life for their families. We had fresh vegetables and bread straight out of the oven. Building community was their work, and so I think I just it was just part of my life growing up and now seems so natural.”

Why We Need U.S. Textile Manufacturing

“Food, clothing and shelter are the things to sustain life. It’s kind of a case of national security that we can’t make our own clothes. We can’t make steel anymore? Does nobody else find that scary? At least the food people have taken that back, they’ve re-empowered the local community, and I hope we’re part of that same movement for material culture. We want to protect the land. And our craftsmen. If we don’t have craftspeople, if we don’t know that as part of our heritage, what happens to the culture [of textile work]?”

What Makes the South a Soulful Place

“Writers have written novel after novel and story after story about the Southern sense of place. There’s a kind of wildness to the South that you can’t put your finger on. Maybe it’s the connection to nature. There is loudness in the nighttime and then the snow and the heat and all of these things that make it feel alive. Maybe it has to do with tornadoes and Mother Nature knocking on your door. Maybe that’s what makes Southerners want to live a little deeper.”

There is an arresting casualness about this corner of Alabama that informs artists and makers. It’s not that the local fashion firms anchored by Reid and Chanin don’t mix with the music industry established here four decades ago; but the interaction is not deliberate — it’s more of a family vibe, with intergenerational hangout sessions at local restaurants or in Wilson Park to listen to live music. Songwriter John Paul White (formerly of the Civil Wars) and keyboardist Ben Tanner (who plays with the Alabama Shakes and others) can be spotted all over town, going about their business of cultivating a new generation of musicians with their label, Single Lock Records. The old guard, like sound engineer and guitarist Jimmy Johnson of the original Swampers, gives public tours of area studios and will answer questions for hours. The Swampers were the backing band of FAME Studios and later Muscle Shoals Sound Studios. They played on some of the biggest pop and soul hits of the 1960s and 1970s — Wilson Pickett’s “Mustang Sally,” Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman,” The Staple Singers’ “I’ll Take You There.” Want to know everything about the night the Rolling Stones recorded “Wild Horses” in Sheffield, Alabama? Just ask Johnson. He was there.

This essay could not be written from the point of view of a magazine editor who flies into the region once a year to attend an epic party called Shindig, where on Court Street in downtown Florence she can buy Reid’s fine wovens at deep discounts and marvel at the yumminess of Odette bistro’s catfish grits while ordering bespoke whiskey cocktails and ogling handsome alt-country god White in the booth next to her. Rolling Stone and The New York Times have already told those versions of this story — the one where Florence stylemakers Reid and Chanin create “his and hers” mini fashion empires just a stone’s throw from the Tennessee River and bring textile manufacturing back to the once-proud “T-Shirt Capital of the World.” Or the Yankee who might think that none of Chanin’s or Reid’s accomplishments would ever have been possible if Bronx-born music producer Jerry Wexler had not decided to bring Memphis-born Aretha Franklin back down South in 1967 to record “I Never Loved a Man (the Way I Love You)” in Muscle Shoals.

As is true of many places in the Southeast, artists in Alabama have felt the need to migrate to the epicenters of the music or fashion industry in order to find work or build an audience. When they leave a place the size of Florence, John Paul White says, they become tiny fish in a giant pond — one of legions in New York or Los Angeles who are trying to accomplish the same thing, whether that be fashion design or songwriting.

“They lose the support network of friends and family and often can’t afford the huge increase in cost of living,” he says. “Only when artists realize that leaving can actually hurt their chances and [erode] their grassroots identity, can they begin to understand the nurturing benefits of a small town.”

In 1961, just after “To Kill a Mockingbird” was released, Alabamian Harper Lee sat in her rent-controlled apartment on New York City’s Upper East Side and lamented in McCall’s magazine about trading her tiny hometown of Monroeville and its “open-door gusts … that cut through the aroma of pine needles and oyster dressing” for Manhattan’s “distant skyscrapers [that] shone with yellow symbols of a road's lonely end.” Similarly, in 2000, Chanin found herself living in the storied Chelsea Hotel, sitting at an old ironing board and stitching couture T-shirts that she sold for up to $400 — a necessary but lonely existence flooded by childhood memories of her grandmother “sewing all the time, making pickles and putting up food for the winter” and by daydreams of visiting her son, who was living in Alabama.

“I was taking planes back and forth,” Chanin says of her stints away from Alabama while in New York, Austria and India. “I was still very deeply rooted in the South, and family was always really important to me. I remember flying in and seeing that red earth around the airport, and it would just make my heart sing.”

For Southerners, it is the tug of home that never goes away.

“Staying or leaving is an incredibly personal choice for creative people like musicians, artists and designers,” says White. “Everyone has his or her own path to follow.”

Florence may feel like a bit of an anomaly in its embrace of music and fashion, but it is becoming a model community for ways to foster local culture and support makers — and a bellwether for change in other Southern towns. The gorgeous University of North Alabama was built as a teacher’s college in 1830 and now spills out into Seminary Street, (where, during my visit, the historic Shoals Theatre hosted a surprise Alabama Shakes concert for the Shindig crowd); the whole downtown welcomes tourists and hosts student populations in the same inviting, walkable way that Athens, Georgia, and Asheville, North Carolina, do.

“Here, people have started linking arms with like-minded individuals to create change instead of just waiting for things to happen,” White says. “Here, we can make our noise far away from New York or Los Angeles, and be a click away from anyone's desk or home. Selling yourself has diminished; whether you’re writing songs or designing clothes, creating your best work is what’s paramount.”

As we leave Florence, it occurs to me that so many stories have already been written about Alabama Chanin, Billy Reid, the long history of Muscle Shoals and its influence on the current music scene as well as the economic reinvigoration of Northwestern Alabama. It’s clear that the thread is community and the family of stitches are the artists who live and work in the region.

Yet, only Southerners might understand what it means to be a maker in the South. To take on the burdens and the heaviness and the soulfulness. To remain connected to the land. To spend half of your life wanting to leave the South. To think you found your fortunes somewhere else, then to return to Alabama and somehow beat New York at its own game.

“If you can make it there, you’ll make it anywhere,” the old song we all know promises. Many Southerners have journeyed far and wide only to realize that some things are better made at home.