The Magic of Athens

How Three Women Found Their Artistic Callings — and Their Home

— in the Everyday Beauty of Georgia’s Favorite College Town

Story by Nancy Lendved | Photography by Rinne Allen + Kristen Bach

It's the mid-1980s, and I'm dancing in my living room in the Adams Morgan neighborhood of Washington. I'm listening to Elvis Costello’s “Imperial Bedroom,” to the Police's “Synchronicity,” and I'm listening a lot to R.E.M.’s “Murmur,” trying to decipher Michael Stipe's lyrics, but I can't: He's murmuring. I feel like I'm hearing a foreign language, but this one doesn't distance me; it pulls me in, it makes me sway.

For a few years, R.E.M. provided the soundtrack to my comings and goings around D.C. I’d take the Rockville Highway to shop at a fabulous fabric store in suburban Maryland, and I’d sing along to “(Don't Go Back to) Rockville,” loudly and off-key. Living in Washington often felt unsettling, the lines between local news and global news blurring all the time, so when I heard Stipe sing, “Empty prayer, empty mouths, talk about the passion / Not everyone can carry the weight of the world,” the words seemed spoken not only to the powers that be, but also directly to me.

I wanted to know more about the small Georgia town with the big world view, the place from which this lyrical language emanated, so when the documentary film “Athens, Ga. Inside/Out” came to town, I grabbed a friend and we watched, excited in the dark. In addition to concert footage and interviews with legendary local bands like R.E.M, Pylon and the B-52s, the film featured Howard Finster, an “outsider” artist who had collaborated with Michael Stipe on the cover of "Reckoning." I’d recently begun collecting Southern folk art, so the visual drew me further in than even the music had. This town intrigued me.

My fate was sealed in 1987, when a friend invited me to ride with him to attend the Rainbow Gathering, on the border of North Carolina and Tennessee in the Nantahala National Forest. If I had to choose between yuppie and hippie, I’d characterize myself as the latter, but the Gathering of the Rainbow Family, held every year around July 4th in a different national forest and attended by thousands of people who remained quite attached to the tie-dye life, was a bit outside my realm.

I'd heard of the Rainbow Gathering just once before, from a friend of my late husband's, whom I met for the first time at my brother-in-law's wedding not terribly long after John had died. One would think that the highly emotional circumstances of that setting would render most casual conversation forgettable, but that reference to the Gathering, tossed off perhaps three years earlier, somehow stuck with me. There was a compelling reason for me not to leave town on a road trip: I was a photo stylist with a huge shoot schedule ahead of me. But I was determined to get to the Nantahala Forest; I felt compelled to go. I booked a flight.

There, on a mountaintop in Nantahala, on the edge of all the activity energizing everyone – the drum circles and the kids' camp, the meditation tents and the camp kitchens – was a man observing from the sidelines. I approached him, and when he told me his home was Athens, Ga., it came as no surprise.

Within a year, I’d sold my apartment, packed up my considerable collection of stuff, and headed South to the place that had been beckoning.

I didn't cross any borders, carry a passport or have to confirm my citizenry, but still, when I joined Andē Burke and his boys in Athens in 1988, I felt as though I'd come to another country. It wasn't just the kudzu – which, I soon learned, only a Northerner would dare deem “pretty,” or the scents of honeysuckle, jasmine or freshly cut hay. It wasn't the music emanating from alleyways on the ramshackle edges of late ’80s downtown. And it wasn't the opossums doing it on the roof right outside our dormer window or digging with their creepy claw-paws through the Meow Mix set out for our cat, Stokey, on our back-porch stairs.

Andē and I went on frequent junking ventures in the country outside Athens to furnish our big old house. I was regarded somewhat suspiciously by the proprietors of these out-of-the-way places. They'd hear my voice and greet me with the astute observation, “You're not from here, are you?” At one antiques store I even got, “What nationality are you?” While this was 25 years or so ago, it saddened me that New York Jews were perceived by some to be something other than American.

But mostly I felt welcome. I was seeing inside and out what I'd gleaned from that documentary, feeling the ease that permeated the place, evident in the locals wandering guilelessly around town in their paint-spattered jeans, in the enthusiasm of the artists who plastered their drawings and photos on the walls of laid-back restaurants like The Grit. I'd shake my head bemusedly at the mere pennies and nickels demanded by the parking meters, grateful to have escaped the ever-present prospect of heart-attack tows from soulless downtown D.C. streets to seedy impoundment lots. And I surely didn't miss those suits and ties.

The heat I'd left behind in Washington had felt oppressive. Here, the heat felt soft and sultry. Here, the air felt free.

Falling in love with Andē landed me across the street from a woman named Rebecca Wood, in the Boulevard neighborhood, on Dubose Avenue, quiet as could be. She and Andē were tight, more than just neighbors: Their kids ran in and out of each other's houses; they were more like family. I'd worked with lots of photographers in Washington, but somehow when I met Rebecca, I felt that I'd finally met a “real” artist — not just because she took brush to canvas, but because she saw the whole world through an artist's eyes. Rebecca'd already found success after finishing art school at the University of Georgia, and she was thrilled when every painting at a show in Atlanta bore a red dot, indicating “SOLD.” But this was 1987, when the stock market crashed. By the time she returned to the gallery after “Black Monday,” every dot had been removed.

It was a turning point in Rebecca’s career: She was raising two young children, trying hard to make a living. She knew she had to redirect her energy into making things that were more recession-proof than high-dollar paintings, and by the time I met her, she was branching out, hand-painting china and making jewelry, cards and stationery. The hand-painted sign stuck in her yard directed passersby to the retail establishment set up in her home: the “250 Dubose Saturday Shop,” where she sold her wares from one room.

Rebecca's hand-painted china was charming (like everything else she designed), but she soon learned it didn't hold up well to use. “The problem was that china painting was so labor-intensive and so impermanent,” she remembers today. “That's when I realized I wanted to make plates that would be more durable and last a long time. I didn't know any of the technologies involved; it meant working with clay, making the actual plates, and firing in a kiln with higher temps and different glazes, all of which I knew nothing about, but I knew that's where I wanted to go.”

I'm reminded of a favorite quote: In “As You Like It,” Shakespeare reassures us, “Sweet are the uses of adversity.” Never one to bemoan the past – a crashed economy, paint that chipped off – Rebecca cut her losses and moved further down the road.

Rebecca Wood at work in her home studio.

I saw Rebecca as unconstrained, like someone out of the Omega Workshops, whose artists produced work I had long admired. The members of that experimental design collective, established in 1913 by the painter and art critic Roger Fry, included Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, and other artists of the Bloomsbury Group. Their clients included Virginia Woolf, George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells, W.B. Yeats, E.M. Forster, even Gertrude Stein. All were ahead of their time. The collective managed to survive World War I, but it closed after only six years. Still, the group shook up domestic design in stuffy Edwardian England by incorporating elements from European avant-garde art into everyday objects for the home – tables, chairs, and textiles; pottery and book jackets; even the walls that sheltered them.

Like the artists of Omega, Rebecca saw possibility in everything: in the outline of an oak leaf, in the humblest falling-down shack, and now, in lumps of red clay. In addition to abundant talent, Rebecca had a friend with an abundance of faith in her — not just in her artistry, but in the faith she placed in herself. So when I found a used kiln at some country yard sale, I got it for her. In return, my new-born shop in downtown Athens, Frontier, got stock for its shelves – beautiful plates decorated with leaves, acorns and flowers. I loved this honest barter, so unlike the quid pro quo of behind-the-scenes D.C.

Rebecca set up shop with the kiln in an old produce warehouse in 1991, and before long, the most interesting shops in New York were ordering her creations, notably Barneys and Zona in Soho. My faith in my friend's tenacity had not been misplaced. The kiln helped Rebecca with her own experiments, helped her find the style that would sustain her business and create the durable pieces so many of us now use and hold each day. I told everyone who admired them in my shop back then, “They'll be family heirlooms. Just you wait and see.” True enough, almost 25 years later, many of Rebecca’s earliest pieces from the kiln are now collector’s items.

I've watched R.Wood Studio grow from a little back-yard business, where underemployed “creatives” sought out part-time work, to one of the largest pottery studios in America. I've watched her travel from her long-ago Saturday Shop to being a featured artist in this summer's 25th anniversary Sundance catalog. I've seen how Rebecca transformed that Black Monday 27 years ago into so much color, into so much beauty, every day.

Two years after Rebecca opened her studio, Andē and I traveled to Italy. In Florence, in Zona’s Italian outlet, we stumbled upon a collection of R. Wood Studio tableware. I was astounded that the clay my friend had fired up in her imagination had made its way this far, to be so artfully arranged and displayed, probably by a student much like the ones who assisted Rebecca in her studio and me in my store. I thought there was a good chance they were listening to R.E.M. as they unpacked the shipments in the stock room of this shop in a city where around every corner is an ancient masterpiece.

I realized then that the the scope of our little college town's influence went way beyond its music: Looking at those stacks of richly colored plates and bowls, shaped and glazed by my friends back home, I saw firsthand just how far the magic of Athens could reach.

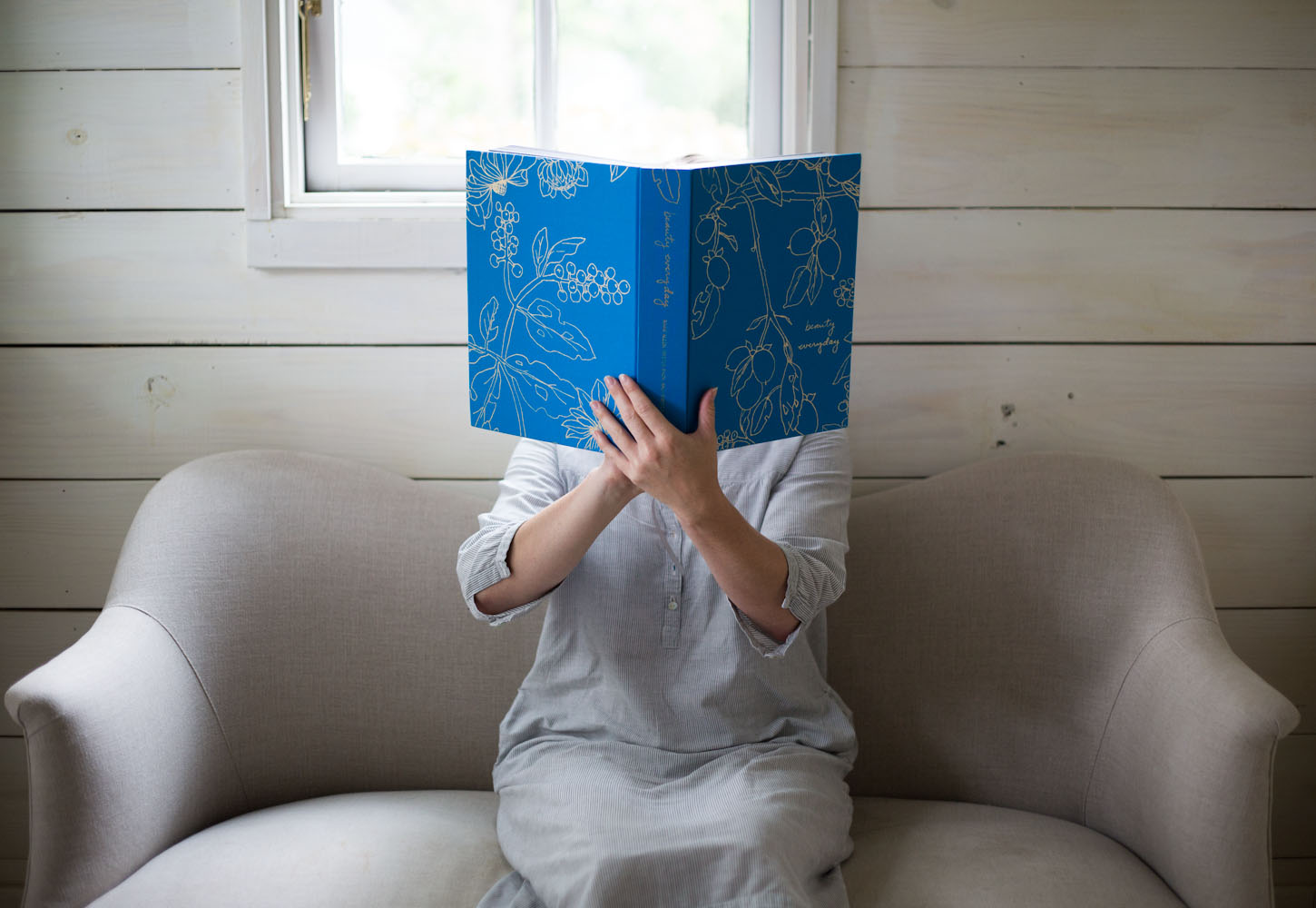

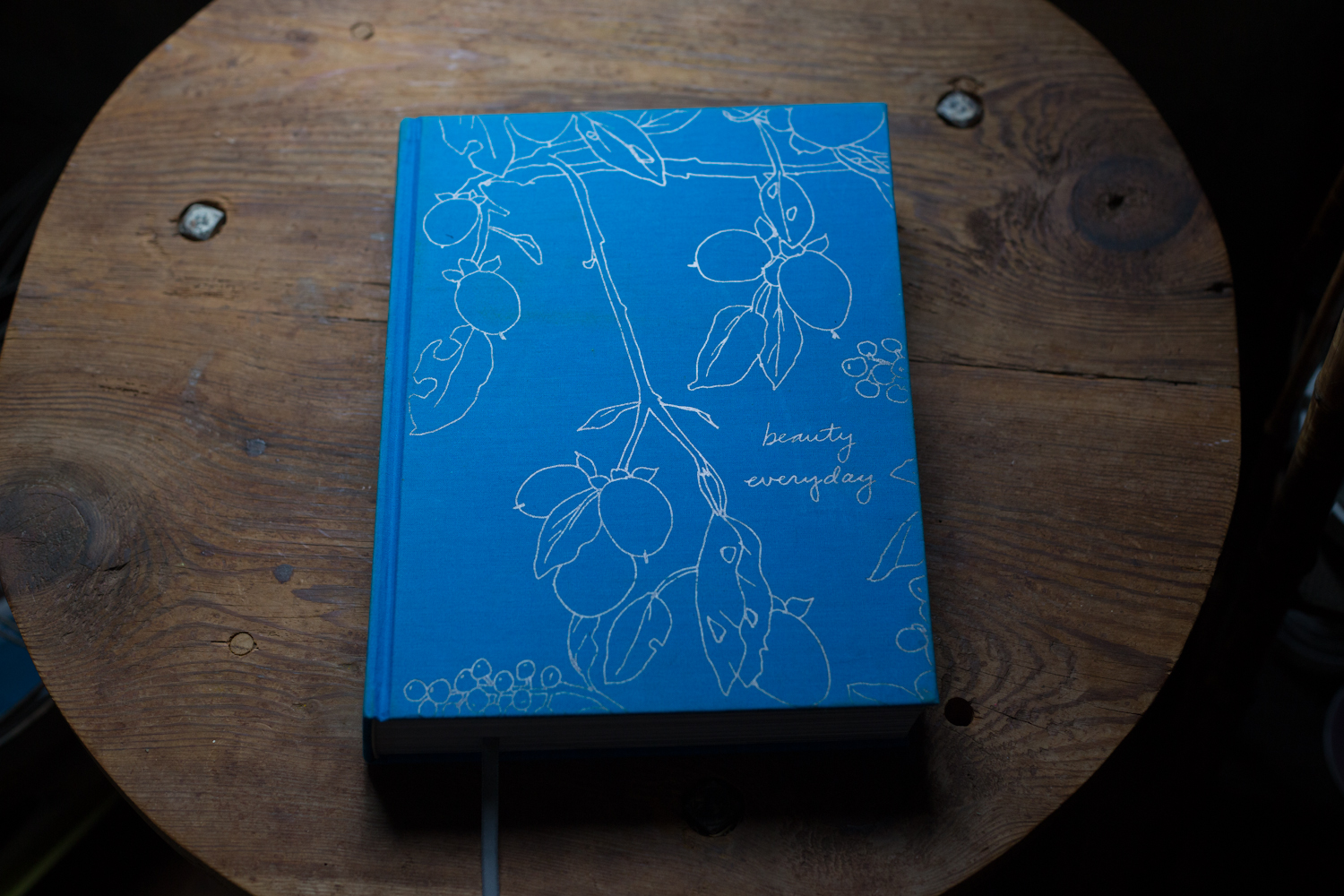

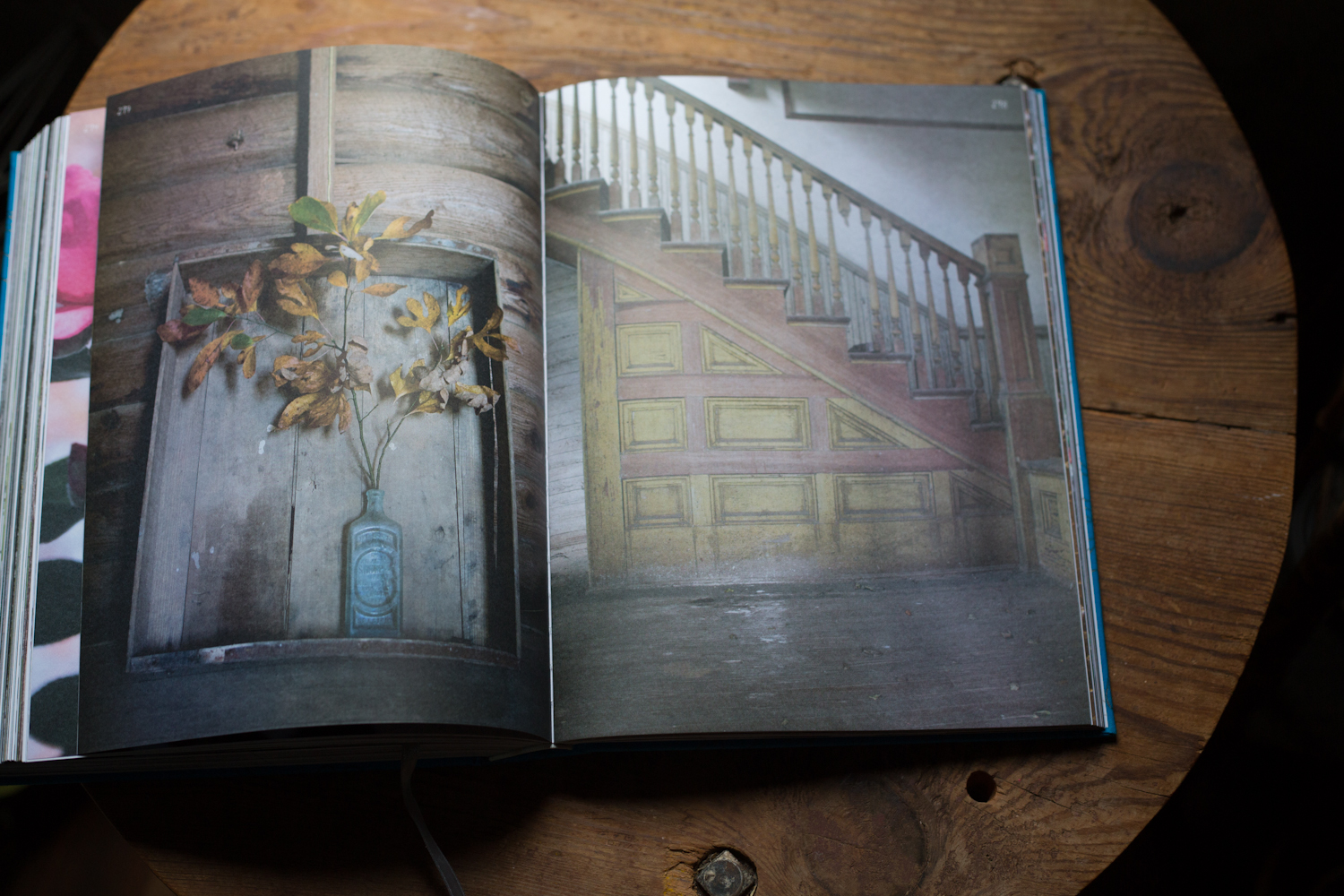

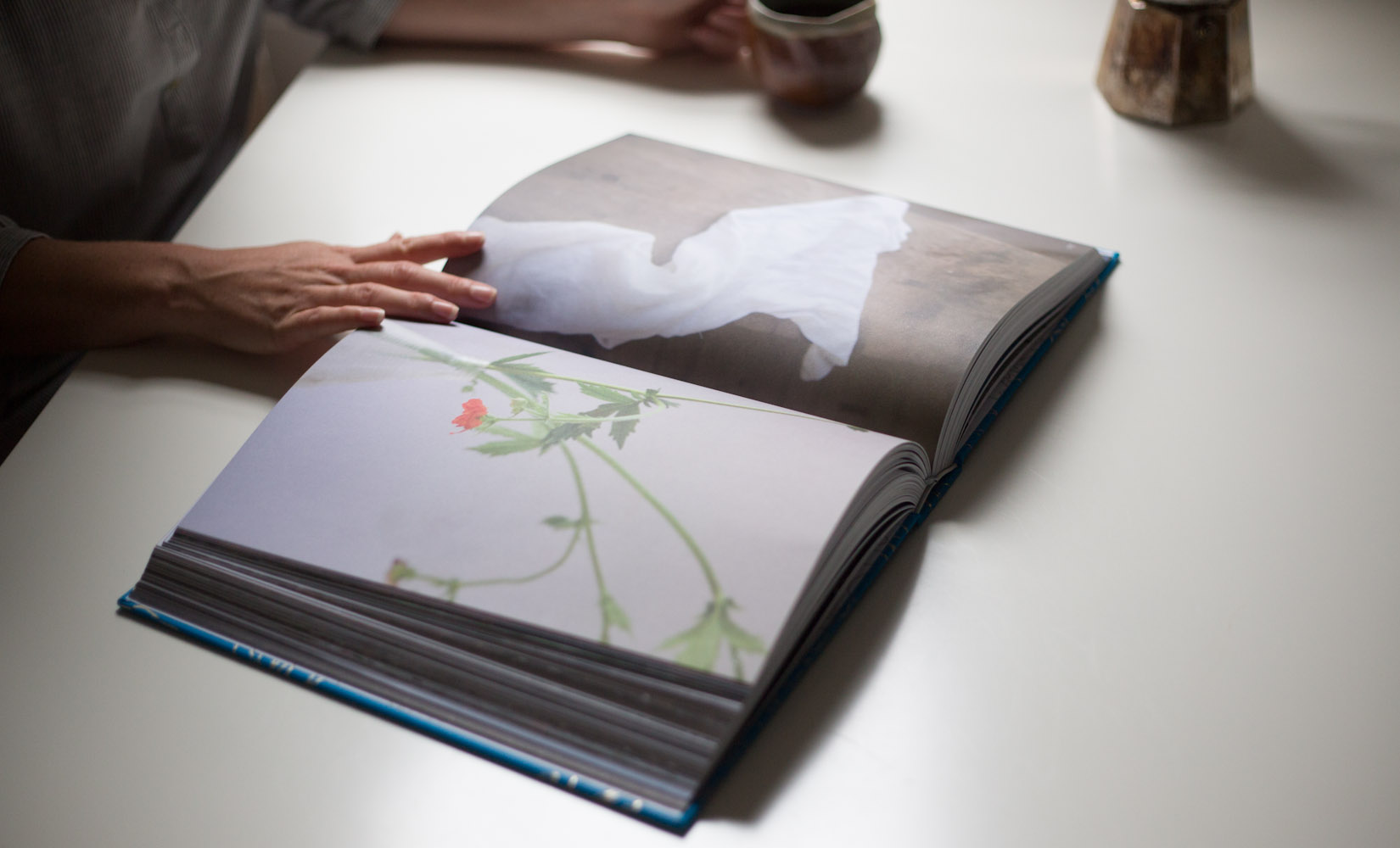

Twenty years later, the magic persists. R. Wood Studio has a global market for its handmade pottery and ceramics. But the company has recently released something that perhaps reflects its inspirations more directly than even its one-of-a-kind ceramics — a huge and beautiful volume of 365 photographs of the built and natural environment in Athens and the rolling rural hills that spread out beyond it. Called “Beauty Every Day: A Year of Southern Beauty,” the book is a collaboration between Rebecca Wood and two of her former R.Wood Studio staffers — Rinne (pronounced “Rin”) Allen and Kristen Bach.

The images inside “Beauty Every Day” reveal the South as we Southerners, native and adopted alike, see it. The book is gorgeous. Its custom-dyed cloth cover showcases a gilded illustration drawn by Rebecca. Rinne says the book is “intended to be an inspiration, a refuge, a reference.” It feels simultaneously soothing and exciting to settle in with this hefty book. The remarkable specificity of the photos makes their commonplace subject matter seem almost magical.

And if there was ever a common thread that runs through most Athens art — its music, its visual arts, its sculptures and pottery — it is that celebration of the commonplace, the idea that the everyday life of the South can be just as compelling as the stimuli of the big city.

Just recently Rinne, Rebecca, Kristen and I spent a day together discussing the trajectory that led to “Beauty Every Day” — a decade-plus path that began 13 years ago when R. Wood Studio added a small section to its website called “Ideas for Creative Living.” I've been privy to fragments of this story from different vantage points along the way, but I want to be told how it all came together, to hear the joy in the voices of these independent artists and businesswomen as they talk about how they became collaborators and friends.

Rinne grew up in Athens, but she attended The University of the South, in Sewanee, Tenn., just as Rebecca did for a while before transferring to UGA. After graduating from Sewannee, Rinne returned to her hometown, thinking she had a “real” job in the art world lined up. When that prospect fell through, she called R. Wood Studio to see if they needed any help. It seemed logical: She was a fan of the studio's ceramics, having discovered and collected pieces at my store, Frontier — which was, she tells me, the source of “all my birthday and Christmas presents.” When Rinne reminds me that she was in high school when she was my customer, I'm startled by the passage of time.

Rinne went into the studio for her interview in 1995 and told Rebecca about the graduation gift her Mom had given her. Flowers and leaves and acorns adorned the earliest R. Wood plates, but Rinne seemed to have received a unique one — perhaps the only vegetable design the studio had produced. As much as Rinne hoped that this connection could be a “sign,” she was disappointed: Rebecca felt “too broke,” she says, to hire anyone else at that time.

Rinne took a job at a local print shop, but a couple of weeks later she got a call from Rebecca, who says he had been moved by Rinne's “cutest thank-you card” to go ahead and invite her to join the staff.

“‘Beauty Every Day’ became our motto,” Rinne remembers, and as early as 2001 they began thinking of creating a book of the same title. They sought a quote from a local printer. When Rebecca recounts her response upon hearing the cost — “Well, we won't be doing that!” – I'm not surprised by her deadpan delivery: Rebecca's persona encompasses the fantastical and the practical in equal measure. The idea was put to rest. For a while.

Instead, they redesigned the R. Wood Studio website and added a section called “Ideas for Creative Living.”

But in the early ’00s, updating a website regularly wasn’t the easiest of jobs.

“It took all you could do to post quarterly,” Rinne says.

Rinne Allen and her work space.

At some point, Rinne officially left R. Wood to focus on her photography career, but she has a hard time remembering exactly when that was because she continued to collaborate in one way or another with Rebecca.

“I started in 1995 and left the day-to-day of the studio in 2001 or 2002, I think,” she says. “It’s hard to believe that Rebecca and I have worked together for almost 20 years.”

Over those years, Rinne has developed an impressive portfolio of work, ranging across food photography, interiors, fashion, botanicals, light drawings and landscapes. The common thread that unites her work is an emphasis on the homegrown, the local, on the beauty to be found in the commonplace. Her interests in gardening and farming and fashion have recently come together in a blog called “Harvest,” which is part of The New York Times’ T Magazine. She accomplished all this while raising two sons, Claren and Bright.

As she grew her photography career, Rinne continued to oversee the R. Wood website, and she and Rebecca still talked every day. It became clear to them that no one was visiting the “Ideas for Creative Living” section, so they decided to “just make it a blog,” and their online journal beautyeveryday.com was born.

That’s where Kristen Bach comes in. Kristen made her way to R.Wood studio in 2004. She grew up in Wisconsin and attended the University of Wisconsin-Stout, where she earned degrees in education and drawing and painting. Like so many before her, Bach and her now-husband Josh Skinner first visited Athens because they’d been drawn there by its music.

“But we both totally fell in love with the landscape and culture,” Kristen says. “It was the beauty of the South that begged for me to take photos.”

She and Josh moved to Athens, and she began volunteering at Daily Groceries, the local food co-op. A fellow volunteer encouraged her to apply for a job at R. Wood Studio. She did, although she was about to begin working at a local frame shop. R. Wood’s studio manager, Claire Campbell, interviewed her. Kristen remembers that there were so many part-timers already on staff, she felt her prospects were dim. But she came home to find a message from Claire saying she was hired at R. Wood, too.

When Kristen arrived for work at the frame shop the next day, she couldn't bring herself to quit. But her first framing assignment changed her mind. She’d been given a painting by Rebecca Wood to frame. She figured the decision had been made for her. She was meant to be at R. Wood.

She didn’t actually meet Rebecca Wood, though, until they met at an art exhibition — a retrospective of paintings by Rebecca and by her former husband, Crawford, Ga., artist Lamar Wood. When Kristen introduced herself as a new employee, Rebecca had yet to learn that Kristen had even been hired; she certainly couldn't have imagined what sympathetic collaborators they would become.

And very soon, beautyeveryday.com become Kristen’s job, with Rinne or Rebecca stepping in to post when Kristen could not.

“In the early days,” Rinne says, “Kristen kept that sucker going. We post five days a week, two times a day. One post is daily beauty – one pic of something seasonal, and the second is more of a photo essay.”

And from that online journal emerged “Beauty Every Day.”

Kristen Bach hangs artwork by some of the kids at her retail and craft space, Treehouse, in Athens.

The three women’s day-to-day reliance on each other is the embodiment of the “relaxed vibe and supportive creative atmosphere” that Rebecca says makes Athens so special. They acknowledge and find peace in the fact that it takes them all to make beautyeveryday.com beautiful, every day.

Kristen was able not only to sustain, but grow, their blog through her five years at R. Wood, where she worked on the studio website as well. In 2009, she left the studio, although she still does postcards and other print work for Rebecca. Kristen soon became pregnant, and while many women would regard this as a time to take a break, impending motherhood had the opposite effect on her.

“I worked through high school,” she says. “I’ve always worked, so now time was moving really slowly. I felt so inspired by having a new little bean in my life. I had the idea for Treehouse during (her daughter) Maypop’s gestation. I had the energy to keep the idea going and to fulfill it — in the worst economic time to open a store.”

“I had a vision to create a place where people in the Athens community and beyond would feel welcome and be inspired,” she says. “I wanted to promote creative play and offer a well-curated shop of ethically made products.”

Mission accomplished. Maypop and Treehouse are both 4 years old. Everywhere one looks in Treehouse, there is something delightful, charming, useful, happy. The shop is overflowing with a brilliantly curated collection of clothes, toys and books that are unified by the theme of Mother Nature as designer, and manufactured in ways that give Mother Nature the respect she deserves. The adorable onesies adorned with woodland creatures are enough to turn one's thoughts to procreation. There’s a ton of color in the shop, much of it evocative of sea and sky (and also, it must be said, of Kristen’s eyes).

Another unifying theme at Treehouse is creativity. She's established a learning and craft center that allows parent and child to appreciate the art of others and to explore their ability to create their own. Just being inside Treehouse spurs visions of a future generation of artists who will enrich the Athens community. And those who scatter, who venture out beyond the “borders” of magical Athens will surely sow the seeds of creativity stashed away in their little-kid memories.

The roster of classes is impressive. I ask Kristen, “What do you teach 2- or 4-year-olds about art history?”

She answers, “We start off with cave painting, and then hieroglyphics, then Grecian vases. That art history class has been so adorable.”

Rebecca is rightly proud of her collaborators Rinne and Kristen, and she will probably see much more of them now that she too lives in town. For years, Rebecca preferred life in the countryside outside Athens, but last winter's polar vortex and the dark wooden walls of the old schoolhouse she'd been renting left her longing for someplace warm and light.

When she heard about a house that was available right across from Chase Street Elementary, she thought she remembered the place. She remembered admiring it, its front yard a riot of pink phlox, irises, spider plants, Queen Anne's lace, roses, foxglove, daisies and all kinds of perennials. She thought, “It couldn't be that house.” She figured perhaps it was the place on the opposite corner.

But no, Rebecca's dream of a warm and light-filled place was made even more meaningful when she learned that it was the house of flowers that she remembered. Its front garden will have to be resurrected, but the loss of those blossoms to time and trespass was softened by the discovery of a hidden side yard full of old azaleas, dogwoods, camellias, fig trees and mountain laurel, all shaded by a large pecan tree.

A lady named Pearl Malcolm established those gardens (with the help of paper-towel-wrapped cuttings she snitched from Mt. Vernon). She lived in the house until she was deep into her 90s, and she would no doubt be thrilled that Rebecca intends to restore — and then draw — her gardens.

The new home marks another new beginning for Rebecca Wood, just as the publication of “Beauty Every Day” puts icing on the cake of 13 years of collaboration between Wood, Allen and Bach.

Beauty Every Day — the Book

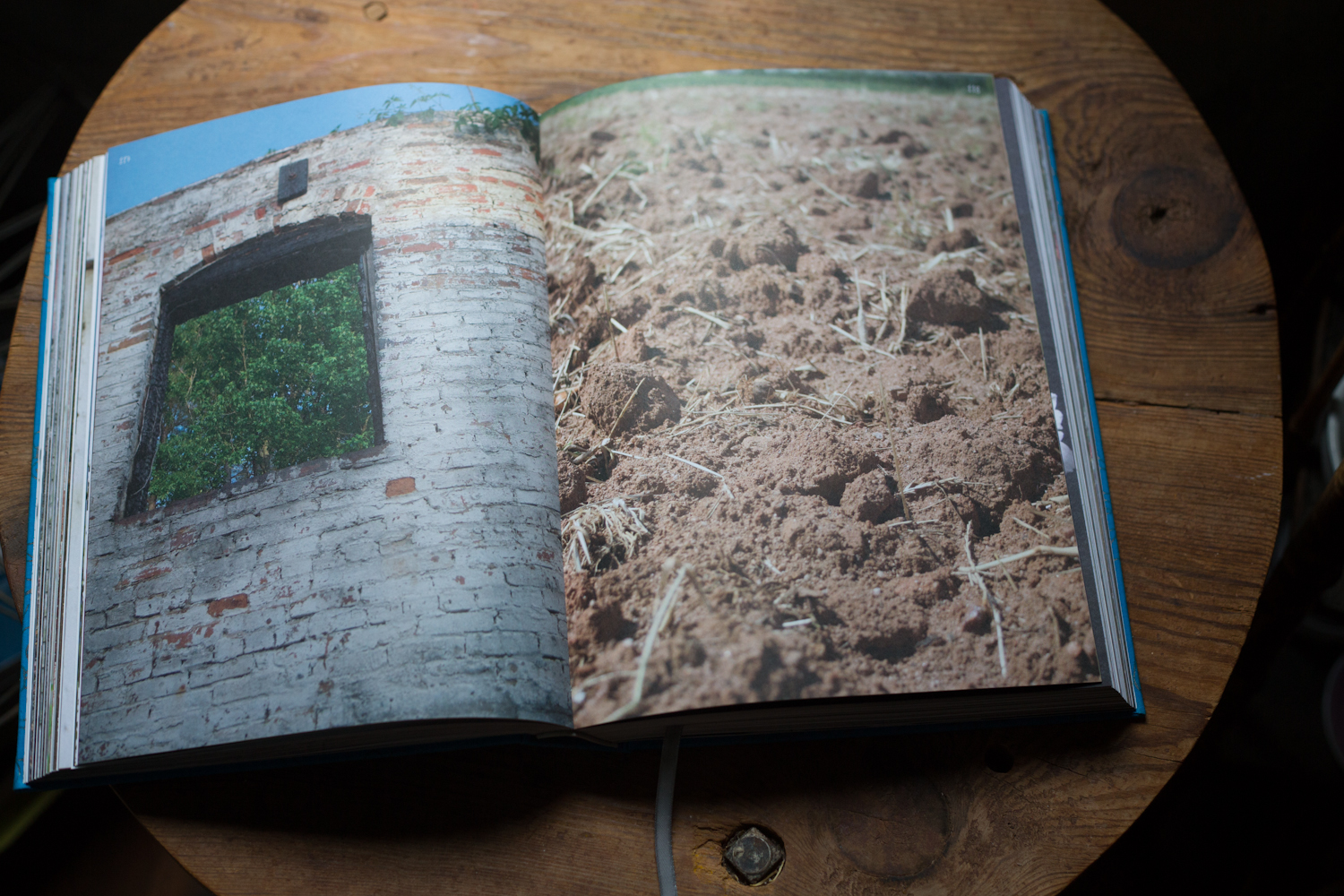

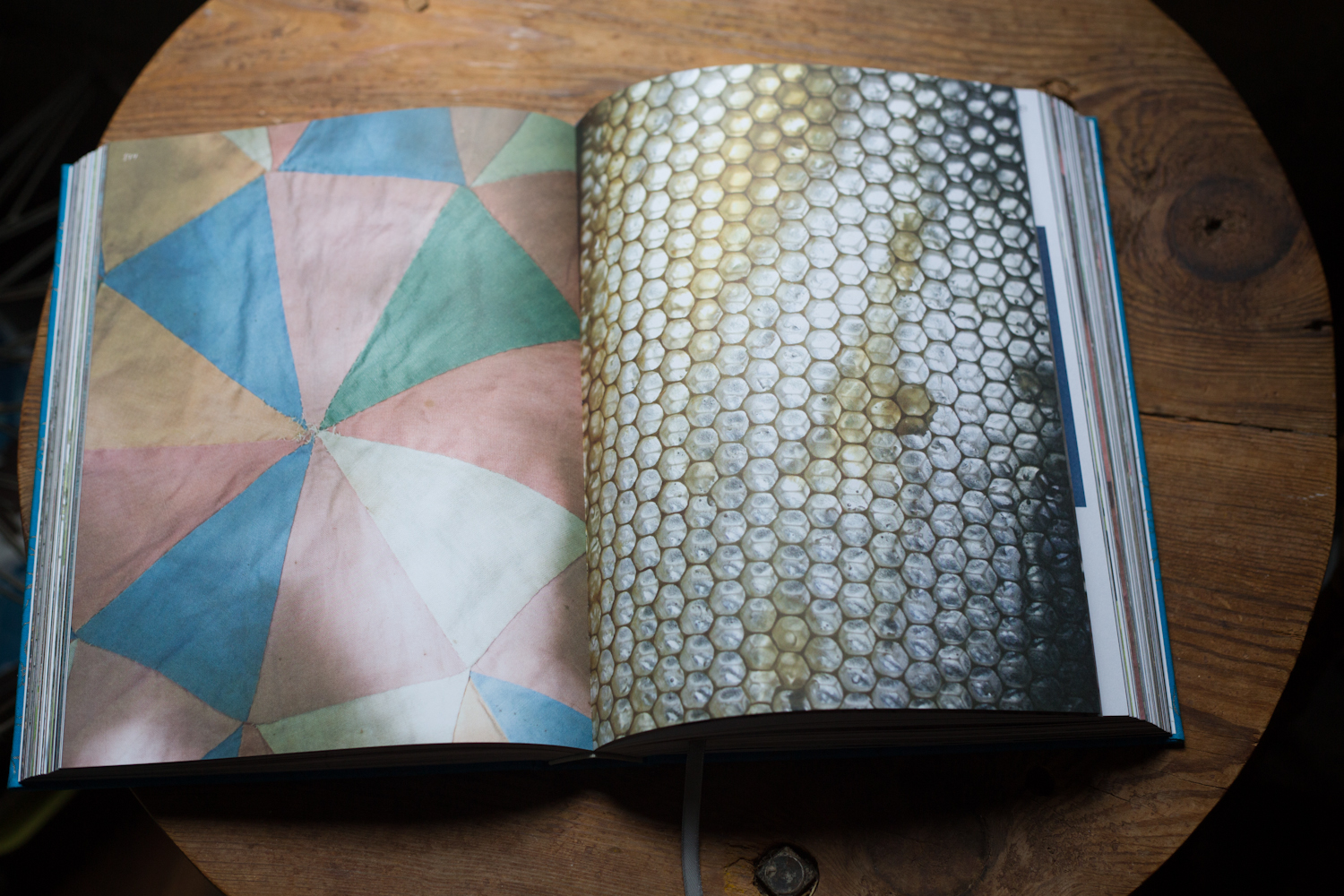

The book’s images flow into one another like the seasons, like time. Brick and bark and vines and berries. Clouds and feathers and fences falling down. Rusty old tin and truck beds teeming with watermelons. Honeycombs, spider webs, pine cones, cotton fields, narcissus and sprouts. Mother Nature's miracles. Stairways, still lives, humble objects shaped and structures built by human hands. Shadows, shimmer; this is our South, our land.

These photos reveal the truth of the South, where not all is shiny bright. These photographers don't shy away from the weathered and the ramshackle. They revel in the same truth that songwriter Leonard Cohen captured in his song “Anthem.”

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack, a crack in everything

That's how the light gets in.

It's said that places explain people. I think these photos of the South say a lot about the women who took them. These people are finding the light.

I hold “Beauty Every Day” in my hands, and I feel pride and gratitude for what these Renaissance women have given us. I remember the words of Lao Tzu, the Taoist philosopher: “Nature does not hurry yet everything is accomplished.” It took years to bring this giant volume to life. The print and publishing worlds were completely upended by technology between the conception of “Beauty Every Day” and its birth. But still, it happened. Rinne and Kristen and Rebecca made it happen.

There is a certain “meant-to-be-ness” threading though their story: Rebecca circling back to painting, working in a light-filled corner of her dream home, determined to restore the garden that enthralled her long ago; Rinne's good manners – an expression of gratitude in a heartfelt note – that led Rebecca to find a way somehow to put her on the payroll; the heart-flip Kristen must have felt when she received that first assignment at the frame shop. I can't help but think all this is just part of the lovely tapestry that is our town's story. Lives remain woven together, connected by all those we touched with our love.

It's been a long time since this place seemed like another country. It's unfathomable these friends could've ever felt like foreigners, or that this community could have felt like anything but home.