A Radical & Wonderful Idea

Cumberland Island is that rarest of places in America, an unspoiled barrier island the size of Manhattan. Few organizations have worked harder over the last half-century to maintain the island than the Georgia Conservancy. So The Bitter Southerner asked Bryan Schroeder, the Conservancy’s senior director of stewardship and outreach, to tell us why he loves Cumberland — and why you should, too.

Once upon a time in Alabama, a man rooted so passionately for the Crimson Tide he devised a plan to make rival football fans at Auburn University furious. In the dead of night, he drove through Auburn loaded up with herbicide looking for his victims. I imagine a Nick Saban photograph on his dashboard, facing outward, so Coach Nick could be his guide.

Roll, damn Tide.

Harvey Updyke Jr., the man in question, poured his herbicide into the roots of two landmark oak trees at Toomer’s Corner in downtown Auburn, then called Paul Finebaum’s popular sports-talk radio show to brag about it.

Updyke got his wish. Auburn fans were furious. In fact, they lost their damned minds. If you dabbled in social media back in January and February of 2011, Facebook was a wall of Auburn orange and navy blue — and pictures of those two trees. I’ve never been to an Auburn football game, but I can imagine what made folks so upset. It was an attack on their memories and experiences with friends, family and loved ones, as kids, college students, parents and grandparents. Parts of their culture, family and sense of place were all wrapped up together under those trees at Toomer’s Corner.

So the Auburn fans lost their minds over the desecration of just two oak trees, and Updyke went to prison.

It just so happens that in May of 2011, as the buzz from the attack of the Auburn arbor assassin was subsiding, another environmental catastrophe was taking shape in the Deep South. More than 38,000 fish turned up dead in the Ogeechee River over an especially hot Memorial Day weekend. As the Georgia Environmental Protection Division, Georgia Department of Natural Resources and the Ogeechee Riverkeeper raced to find the culprit, they discovered elevated levels of chemicals that under no circumstances should be in the river. It was discovered that King America Finishing, located in Sylvania, Georgia, had been illegally dumping formaldehyde, ammonia and hydrogen peroxide into the Ogeechee River for last five years.

Chew on that for a second. Five years of absolutely illegal, harmful and unregulated pollution.

The Ogeechee River is an incredibly beautiful, vulnerable, biologically diverse river, and for five years, King America Finishing had gotten away with dumping chemical pollution in the river so the company could make more profit.

I don’t recall Facebook catching fire when King America was caught poisoning the Ogeechee. If so, it was only a handful of my environmentalist friends. Otherwise, no one really cared. Well, maybe they cared, but not deeply. As for me? I had never been on the Ogeechee, but I was thinking my grandpa paddled it, maybe. Sure, the pictures are beautiful, and I was upset, but what could I do or say about a place I had never visited? Who really cared about the Ogeechee River? A hearty few river folks and passionate environmentalists, for sure, but enough voices to constitute a groundswell of support? No.

It took years to bring King America to “justice,” and the company almost got off the hook. The Ogeechee Riverkeeper, GreenLaw and Atlanta environmental Don Stack did amazing legal work in the face of incredible odds. King America was slapped with fines, but none of its executives spent a day in jail. Not one individual faced a penalty. King America was later sold, but the factory is still in business today, with a new permit, pumping slightly less pollution into the river.

If we loved the Ogeechee River the way folks in Auburn loved those two oaks in Toomer’s Corner, the roar of discontent would have shaken the foundations of King America Finishing. Its owners and operators, having willfully poisoned the Ogeechee for more than five years, might have found themselves in jail, just like Harvey Updyke.

If you think the 2011 Ogeechee River Fishkill is an isolated incident, think again. The South is brimming with critically endangered habitat. These places are underappreciated, and they are under constant threat. I’m lucky to work at an organization where I feel like we can make a difference: the Georgia Conservancy, which for almost half a century has advocated for the state’s environment and for land conservation.

It’s not easy watching the places you love being exploited. But if you are in the business of conservation, as I am, I see it happen all too often. Sometimes it feels like an an unending MadLibs game with that John Prine song, in which any number of natural wonders and corporations could be substituted for the Green River and Peabody’s coal train.

But at the Conservancy, we’re taking a page out of the Toomer’s Corner playbook to protect some of Georgia’s most precious places. Our goal is to take thousands of people into Georgia’s most beautiful and most threatened habitats. We want to make them love those places as deeply as Auburn fans love the trees at Toomer’s Corner.

You see, I believe that if you want folks to care for a place in this world, they’ve got to connect with it. Not just see it in pictures or glance at it from an overpass. Folks need to experience it. Get close to it. Get it under their fingernails. It should be the destination of their daydreams and impromptu road trips. The connection they feel to it should approach the sublime.

So over the next 12 months, we will lead 3,500 people on hiking, paddling, camping and service trips to far-flung and unheard-of natural places while celebrating conservation, culture, food, music, diversity and family. We are in the business of conservation, yes, but to succeed, we must also be in the business of love. Love for the rivers, the barrier islands, the marshes, plains, canyons and even urban parks and the cities that surround them.

We want folks breaking bread on Georgia’s riverbanks or singing songs around a campfire, from the mountains through the coastal plain and to our amazing saltwater-marsh ecosystem and barrier islands. Our goal is simple: Create a connection between some of Georgia’s most underutilized, stunning natural places and the people we need to help us protect them.

In 2015 we’re leading or have led trips to the Ogeechee, Altamaha, Ocmulgee, Oconee, Flint, Ochlockonee, Chattahoochee, Satilla, Suwannee and Conasauga rivers; to Ossabaw, Sapelo, Cumberland, Blackbeard and Little St. Simons islands; to Okefenokee Swamp, Cloudland Canyon, Frick’s Cave, Howard’s Waterfall Cave, Panola Mountain, Broxton Rocks, Radium Springs, the Len Foote Hike Inn, Augusta Canal, Ebenezer Creek, Sweetwater Creek and the mighty Cohutta Wilderness.

As a Georgia native, I find these experiences eye-opening and heartening. Many times, I've been a first-time visitor myself, just like many of our guests. I’ve paddled rivers I’d never heard of, explored canyons and caves I had no idea existed, snorkeled through clear mountain streams and visited remote and restricted barrier islands.

Inevitably folks ask me, “Where should I go? If I only take one trip, what would you recommend?”

I don’t even have to think about my answer. Heads and shoulders above every creek, stream, river, marsh, canyon, mountain and island in the state, there is one place so beautiful, so majestic, so special that anytime someone mentions it, my heart immediately begins to pine for the way its sunrises illuminate its live-oak forests.

It’s called Cumberland Island National Seashore.

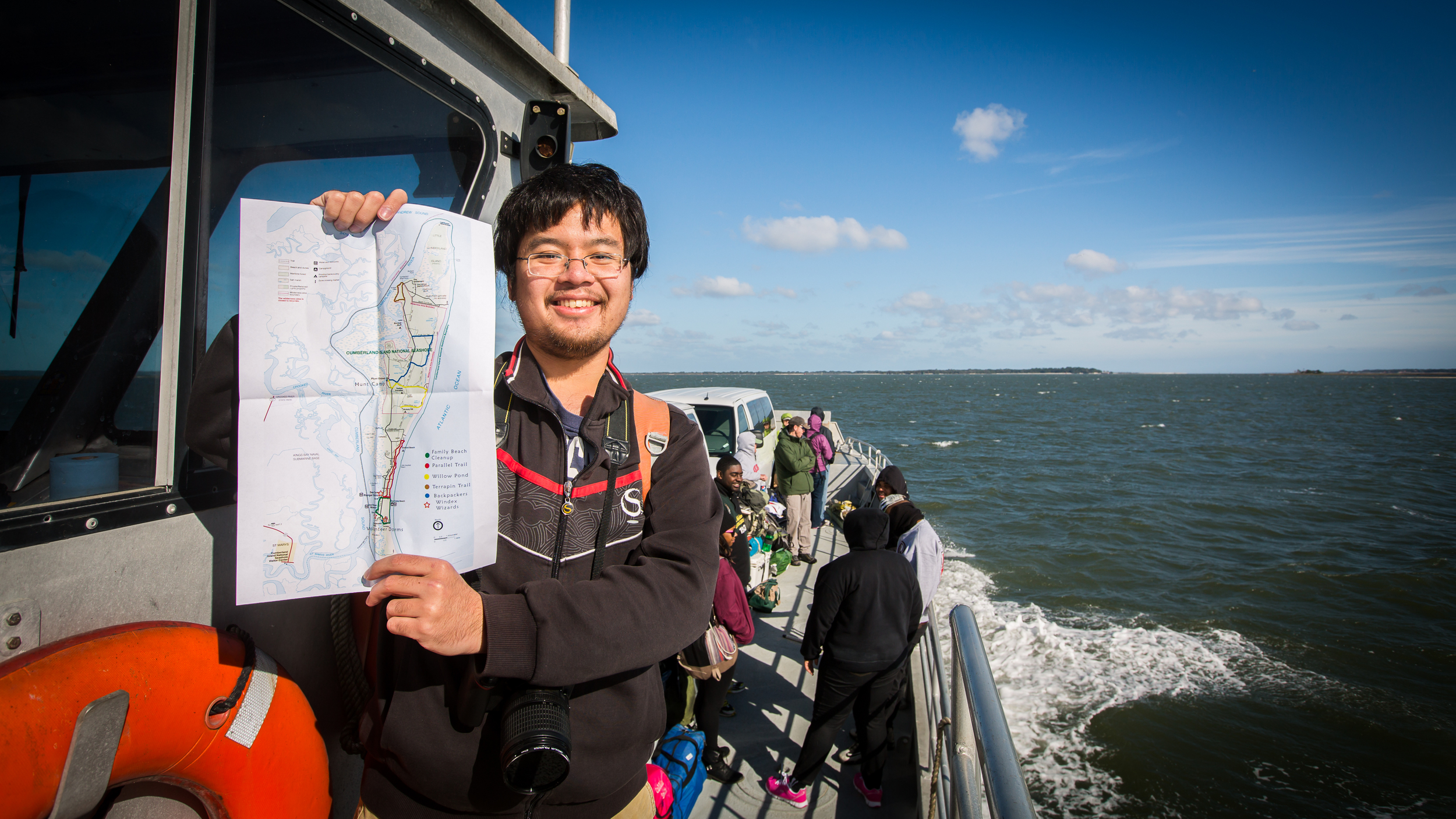

All photos (except where noted) were shot during the Georgia Conservancy's 2013 Cumberland Island Service Weekend, over the Martin Luther King Jr. Day holiday.

Early last summer, I went to Criminal Records in Atlanta to drop some cash on reissued ’70s Afrobeat vinyl. Fela Kuti had gotten under my skin and I had an itch to scratch. At the checkout line I took the opportunity to pick the brain of the clerk. In the most “record store dude” sort of way, he went on and on about a particular artist from Ghana, his style, his influences, his odd guitar tunings, etc. The kid knew so much about the musical value and influence of an artist from another continent and another generation.

Next to him at the register, a copy of “Dereconstructed,” the widely lauded 2014 album from the South’s own Lee Bains III and the Glory Fires, was on display. At the time, Bains himself was living about 50 yards from where we were standing and had played a solo, in-store show at Criminal the week before.

I asked Record Store Dude, “What do you think about the Glory Fires’ new album?”

Record store dude: “Who?”

We all suffer from a tendency to look right past the world around us and place value in the exotic and faraway. With that in mind, I’d like to ask you to quit planning your vacations to Lake Tahoe, Glacier, Olympia, Grand Canyon, Redwoods, Yosemite. All those places, they can wait. It’s time to explore, appreciate and exalt the natural beauty of the American South.

And the best place to start might be Cumberland Island.

Cumberland Island National Seashore, a Manhattan-sized barrier island brimming with unparalleled natural beauty from top to bottom (much like Manhattan Island itself in the early 1600s), lies off the coast of Georgia and managed by the National Park Service. Stunningly pristine beaches, picture-perfect dune system, haunting forests of palmetto and live oak, interior freshwater ponds, saltwater marshes, historic ruins, standing historic mansions and an unbelievable history — from ancient times up through the gilded age — Cumberland has it all.

The walk from the Ice House museum on the western side of the island, past the Dungeness ruins, through the historic graveyard, along the boardwalk through the marsh and the giant sand dunes is one of the best examples on the East Coast of barrier-island biodiversity and how sand dunes build and rebuild themselves if left to nature’s devices.

It’s a breathtaking experience, with so many simple and beautiful ways to connect with the island:

Find a still spot in the maritime forests and listen to the wind blow through the palmettos, shaking the live oaks. If you pick a spot anywhere on the south end of the island, you can hear the waves during high tide, an unseen crash through the forests.

Wake up before dawn, brew a strong cup of coffee and make your way by starlight to Cumberland’s pristine beaches. Plant your feet in the sand and watch as the sky changes from black to blue and the dunes behind you transition from pink, to yellow and finally to white.

Think about the men and woman who have passed through these trails: Native Americans, enslaved Africans, European explorers and then the plantation owners, steel barons, soldiers and political elite who once called Cumberland home.

Convince your friends to hike eight miles to Plum Orchard, have a drink on the front porch of a white-columned mansion built in the wilderness of Cumberland and then eight miles back through the forest where you spend your evening around a campfire, stargazing.

If you’d let me, I’d stand on your coffee table in my cowboy boots and declare explicitly, unequivocally and without qualification that there is no more important natural and cultural place in the South than Cumberland Island. I’d double down on that claim and tell you that Cumberland Island ranks with the best natural places in the United States, easily in the top five alongside the “epic” and “iconic” natural places you’d find out west.

Don’t worry. I’m not just being a homer. Check out these paragraphs from an email I got recently from Charles Seabrook, the veteran journalist who is one of the most passionate defenders of Southern barrier islands such as Cumberland.

After serving nine years as the superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, the first woman ever to hold that position, Suzanne Lewis, retired in 2010 after an illustrious career with the National Park Service. Prior to that, she was the superintendent at Glacier National Park and, before that, the Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area. She was also the first superintendent for the NPS's Timucuan Ecological and Historical Preserve in Florida. But during all those years, another place, Cumberland Island National Seashore, was near and dear to her heart. Even though she lived in and was the chief custodian of some of America's most superb natural splendor, she says that Cumberland's serenity and solitude are unmatched.

And so she wants the island to be her final resting place. "It's in my will: When I die, I want my ashes strewn in the marshes of Cumberland," she said in an interview. While she loves all of the island, she said that the salt marsh is her favorite part. "The marsh is so peaceful and yet it teems with life," she said. Cumberland, she added, still tugs at her heart as strongly as ever:

"Cumberland Island has the greatest abundance of 'riches' that I have ever encountered. The collection of 'riches' in one place is 'unique,’ a word used too often and many times inaccurately, but not when it comes to Cumberland. These 'riches' are both immediate and subtle, from the sights and smells of the marshlands, forests, ocean and ruins to the 'sounds' that call to you once you are on the island. These sounds represent the 'voices' of both the natural and cultural riches found on the island. From the first time I visited the Island in 1979, I have felt that calling. Now some 36 years later, I look forward to hearing those welcoming 'voices,' calling me back, time and time again.” For someone of Suzanne Lewis's stature, that is a remarkable statement about Cumberland Island.

The Georgia Conservancy began its work on Cumberland Island in the 1960s and has been a part of every decade of advocacy and education work, including our work with the National Park Service, whose role on the island began when it was designated a National Seashore in 1972. This fall, the Conservancy and the NPS will launch the Cumberland Island Trail Restoration Project, a joint effort to significantly improve Cumberland's iconic backcountry trail system, using funding from REI and the M.K. Pentecost Ecology Fund. The project includes significant trail clearing, signage improvement, GPS trail mapping and the creation of the first professionally designed backcountry trail map in Cumberland Island history, featuring trail descriptions, mileage, habitat and more.

The Trail Restoration Project originated from an annual service weekend. For the last seven years on the the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday weekend, more than 75 men, women and children come from across Georgia to spend the weekend working on trails, cleaning beaches, historic restoration and working on building projects. Some folks would stay in dorms, others would stay in a volunteer-only campground. The Martin Luther King Jr. Cumberland Island Service Weekend has been a success, both on the impact on the island and on the participants.

In 2010, we added a backpacking group comprised primarily from students from historically black colleges and universities in Atlanta. For many of the students, it wasn’t just their first time on Cumberland, but their first time backpacking, camping and sleeping outdoors. Students from Spelman and Morehouse have been back every year since, making an incredible impact with their volunteerism and stewardship. After their trip, they take back to campus epic tales of campfire meals, grueling hikes, sunrises and stargazing. Cumberland service has become somewhat of a campus tradition, if not a rite of passage, for certain students at those historic schools.

The 2010 HBCU students, however, were trailblazers, and not so sure about the task at hand. They were the first, and in the minds of some, potentially the last. During orientation on the island, going over maps, passing out meals, giving a pep talk to the first-time campers, one of the students stopped me and said, “Excuse me, I was wondering, this is the MLK Service Weekend on Cumberland. What exactly does Martin Luther King Jr. have to do with Cumberland Island?”

Damn.

How do I answer this question honestly?

For the most part, the trip was scheduled over the MLK Holiday because of the weather in January and the day off on Monday for most folks to travel home … but that’s about the lamest answer you could give.

I did some lightning-fast soul searching. Cumberland Island history and beauty raced through my mind on one side, alongside the life and teachings of Dr. King on the other. If you could have cracked my head open and peaked inside, it would have looked like a bizarre slot machine, spinning images and looking for a match.

Suddenly the bells went off.

“Well, let me tell you a story about garbagemen in Memphis,” I said, and my mind turned to the memory of a preacher, the Rev. Billy Kyles.

On April 4, 1968, the defining moment in the life of the Rev. Billy Kyles arrived like a thunderclap as he stood on the steps of a motel in Memphis. His party had spent the last hour acting like giddy children free from the watchful eyes of their parents, playful and spirited — even pillow-fighting — in room 306 of the Lorraine Motel.

Rev. Kyles turned to speak to his dinner guests as Dr. Martin Luther King stepped through the threshold of the motel-room door, leaned across the balcony railing and teased Jesse Jackson for being underdressed. Dr. King pivoted his body toward the stairway as Rev. Kyles admonished the group, “Come on guys, we’re going to be late.”

Dr. King never took another step.

Thirty years later, I listened to Rev. Kyles share his story with a student group from Piedmont College while I participated in a Civil Rights tour of the South. I was absolutely stunned. Standing in front of me was a man out of history, a photo come to life. (You know the photo from the history books: men and women, including Rev. Kyles, standing above their fallen leader, pointing desperately in the direction of the shooter.) I still get chills thinking about that moment, and I have not forgotten the words he shared with our group.

After April 4, 1968, Kyles dedicated his life to sharing the story of what happened on the Lorraine’s balcony. As he spoke in great detail, scrutinizing every moment they spent together as they prepared to exit the motel, I was struck by the fact that these were all memories that should have faded into the haze long ago. The pastor small talk they shared. The neckties they selected. The meal waiting at home that would never be served. Insignificant moments that would never be forgotten because as they wisecracked and shot the bull, a gunman waited patiently outside the motel room.

Rev. Kyle's was a storyteller and he paced himself expertly, interjecting humor and laughter, but the doomed fate of the protagonist stalked the main characters out the door of the motel. This story never ends well.

A single shot rings out. Kyles kneels down and holds King’s body. There is blood on the balcony and motel floor and a crushed cigarette in King’s hand (“I took it so children wouldn’t see it in the news,” Kyles said.) Panic builds as he calls the motel office and listens to ring after ring with no answer. He bangs on the wall for the motel operator to answer the phone. The story was heartbreaking and brutal. And even though this was a story Rev. Kyles had told thousands of times, it was an incredibly emotional recounting.

Rev. Kyles took a deep breath and I thought the story was over. He looked back up at our group and spoke very slowly.

“My life changed on that balcony,” he said. “I found my calling and my purpose for the rest of my life. The world can never forget this fact: Dr. King died in Memphis, fighting for the rights of sanitation workers. Think about that. Long ago he could have given up his work in the field. As a scholar and a Nobel Peace Prize winner, he had offers around the world to teach and to write and to live a safe and comfortable life. But he came to Memphis and died fighting for rights of garbagemen. Garbagemen!”

He paused again.

“Since that day, it’s been the purpose of my life to share this story. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. died here in Memphis, fighting for the rights of sanitation workers. Never forget this, and in kind, do what you can for the garbagemen in this world.”

Back on the island, when that young man asked me what Dr. King had to do with Cumberland Island, I used Rev. Kyles as my inspiration.

“So when I think about what Cumberland has to do with Martin Luther King Jr.,” I said. “I think about the garbagemen he died fighting for. This island isn’t just beautiful and historic. It stands for something. A promise American can keep. Dr. King was in Memphis not just because of the financial plight of the sanitation workers, but also the idea that even the poorest of the poor deserve a place at the table in this county. This island was once the playground of the uber-wealthy. Now, it’s an island that belongs to those Memphis sanitation workers. To everyone, the least among us. This is their island too.”

Cumberland is for us all. The garbagemen, the teachers and executives. Servers, designers, farmers, managers, doctors, writers, lab techs and mechanics.

Ask yourself three questions:

Am I a descendent of a wealthy steel or railroad baron?

Am I one of the first people to pilot a transcontinental flight?

Am I a well connected political leader?

If you answered no to any these questions, you would likely have never been able to set foot on Cumberland Island. But all that changed when the Cumberland Island National Seashore was authorized by Congress in 1972. Today, the island ferry runs two or three times a day. The island welcomes visitors, campers and backpackers. Cumberland is open and accessible to pretty much everyone.

In the late 1800’s, Cumberland was an island of exclusivity, owned, for the most part, by the wealthy Carnegie family. Even through the 1950s, as the wealth and opulence that once supported Cumberland began to dwindle, Cumberland was never open to outsiders.

That’s what makes Cumberland Island National Seashore, and all of our national, state, county and city parks so important. Conservation is never an accident. Conservation is never over. Men and women spent their lives (and fortunes) protecting and restoring these places.

It doesn’t matter where you’re from. It doesn’t matter your station in life. We’ve made a public choice to set aside beautiful places for everyone to enjoy. It doesn’t matter who you are or what community you’re from. Even if your cultural norms say, “Oh, we don’t go there,” go there anyway.

Enjoy our precious natural places. Love them. Connect with them. Protect them.

I remember the first time I stepped onto Cumberland Island. It was a family vacation in the late 1980s, when I was about 8. I remember the ferry ride over, looking for dolphins, begging my parents to buy us chips and drinks from the ferry’s canteen, the excitement of seeing our first “wild” horses on the island, searching for the clay tennis court outside the ruins of Dungeness, the rusted cars outside the mechanic’s shed and the incredible live oaks. As a child, the sand dunes seemed like giant white mountains, next to impossible to climb. The pristine beaches stretched out for miles and felt like a mystical paradise. The Sea Camp shower house was like an Amazonian outpost in the middle of the jungle, the last sign of humanity before the wilderness.

That was one of the defining moments of my life.

And it presented itself unexpectedly on an impromptu day trip my parents planned while vacationing on St. Simons Island. I got Cumberland under my fingernails. I got its sand in my shoes. I gathered its seashells as memorabilia.

I was a kid from a modest family in Rome, Georgia, but this island was ours. It belonged to us. It was ours to enjoy and protect. It was a discovery that changed my life forever.

Yes, Cumberland Island once belonged to the Carnegie family. But now it belongs to all of us, garbagemen included.

This is a radical and wonderful idea, but it will wither on the vine without our support.

Photo by Julian Buckmaster