Assembling the Sacred Texts

After 11 Years of Exploring Folk Music Around the Globe,

Atlanta’s Dust-to-Digital Turns Its Sights Homeward

In the digital age, nothing is lost. This, anyway, is what we tell ourselves.

Every event in our lives, even the insignificant, is photographed and squirreled away in the cloud. We journal our lives exactingly in long streams of archived emails and Facebook posts and tweets. Nothing is lost. All is documented. Every item, time-coded to the second.

But amid all this documentation, perhaps we lose something more ethereal. Do we forget the joy of accidental discovery — the thoughts and memories that wash over us when we stumble upon a found object, a real thing in the analog world? What do we learn about ourselves, our places and our histories when we happen upon such things?

Think about the last time you browsed an old family photo album. Or if you’re a record collector, think about the last time you unearthed an old 45 or 78 in the Salvation Army store and brought it home just because you’d never heard the song or even seen the name of the singer before.

We rummage through the photographs because they take us places. They bring questions to mind. Who was this person? Where did she live? What was her life like? We throw the records on the turntable because they launch us into daydreams. Never heard stuff exactly like this, we think. Who were these folks? Where were they from?

Some people make it their business to ensure we don’t lose these accidental moments. Collectors. Obsessives. Documenters of the analog. Many of these people — truth be told — are at the very least eccentric, and some are just flat-out batshit crazy.

A rare few of these obsessives, however, can take the detritus of our culture and recontextualize it in ways that help us understand it anew.

Meet two of them: Lance and April Ledbetter, a pleasant and unassuming couple who live in a pleasant and assuming house in the pleasant and unassuming Ormewood Park neighborhood of southeast Atlanta. For 15 years now, they have documented the folk music, stories and photographs of communities around the world, assembling them into beautifully constructed products. Their company has a name that suits it perfectly: Dust-to-Digital.

From Lance and April, you can buy such things as:

“Longing for the Past: The 78 RPM Era in Southeast Asia.” A 272-page hardcover book with 4 CDs of music in a slipcase. $57.50.

“Never a Pal Like a Mother: Songs & Photographs of the One Who’s Always True.” A 96-page hardback photo book with 2 CDs of vintage recordings from 1927 to 1956. $25.

The Dust-to-Digital catalog includes dozens of such items. If you think there would be no financial reward in such an enterprise, consider this:

The Ledbetters’ have made their mortgage payments for a decade by doing this work.

Six Dust-to-Digital collections have been nominated for Grammy Awards, and the label won the Grammy for Best Historical Album in 2008.

When Bob Dylan is looking for a Christmas gift for his buddy Neil Young, the Ledbetters get a phone call.

And Pitchfork, the biggest indie music blog in the nation, says it’s "astounding how essential … Dust-to-Digital has been to the preservation of traditional American folksong. It’s easy to buy and appreciate these sets without realizing that the bulk of the material might have been lost — or, at the very least, tethered to archives, readily accessible only to curious faculty, paper-writing students, and bespectacled researchers — without Ledbetter’s interference.”

Lance and April Ledbetter are perhaps the most important preservers of folk music in the modern world, and they do it all from the basement of their little brick house.

The first time I visited Dust-to-Digital’s basement HQ about a year ago, Lance Ledbetter was lamenting the sad state of a record-cleaning machine.

Record-cleaning machines are the province of a special breed of music nerd. They are designed to vacuum every last speck of dust and grime from the grooves of vinyl or shellac records. A top-of-the-line machine can run you as much as $4,000.

This particular cleaning machine was on the fritz because it had been used to clean a treasure trove of old 78-rpm records, the collection of a recently deceased Kentucky man. The records would have disappeared into a landfill had they not been rescued by a Kentucky-born archivist named Nathan Salsburg. The cleaning machine had been used to prepare those old grooves for the cleanest possible transfer of the music inside them to digital media. But the records had gunked up the machine with a substance native to their home state: coal dust.

For some reason, that episode has never left my head in the past 12 months. To me, that gunked-up record cleaner symbolizes the essence of what makes Dust-to-Digital special. These brittle old disks — documents (to borrow a phrase from the critic Greil Marcus) of “the old, weird America” — are brought forward into the modern world, and they gunk up the machine.

That’s what this kind of preservation work does. It gunks up our machines. It makes us rethink what we believed about our history. It adds new substance and different perspectives to stories we thought we already knew well.

The Ledbetters have been tremendously ecumenical in their preservations. Dust-to-Digital has issued music, photographs and words from all over the globe: Bali, Burma, Cameroon, China, England, Germany, Greece, India, Japan, Java, Laos, Morocco, Persia, Poland, Portugal, Scotland, Spain, Sweden, Syria, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, Vietnam, Yemen and Yugoslavia. And in 2012, the Ledbetters ventured into new music, releasing "Just Before Music" by the genre-defying Alabama musician and artist Lonnie Holley and then his 2013 album "Keeping a Record of It," which landed at No. 10 on the BS's 2013 list of top Southern albums.

"Their attention to detail is without peer," says Matt Arnett, Holley's manager and the co-producer of both records along with Lance. "They document and present music in a way that no one else does. Whether the music is getting its first release or being reissued, they research and package it in such a way that it remains fresh and revelatory, whether it was recorded a century ago or last week."

But this fall, as it crosses the 15th anniversary of when its first product was conceived, Dust-to-Digital has returned very specifically to its roots, releasing almost simultaneously three projects from the American South:

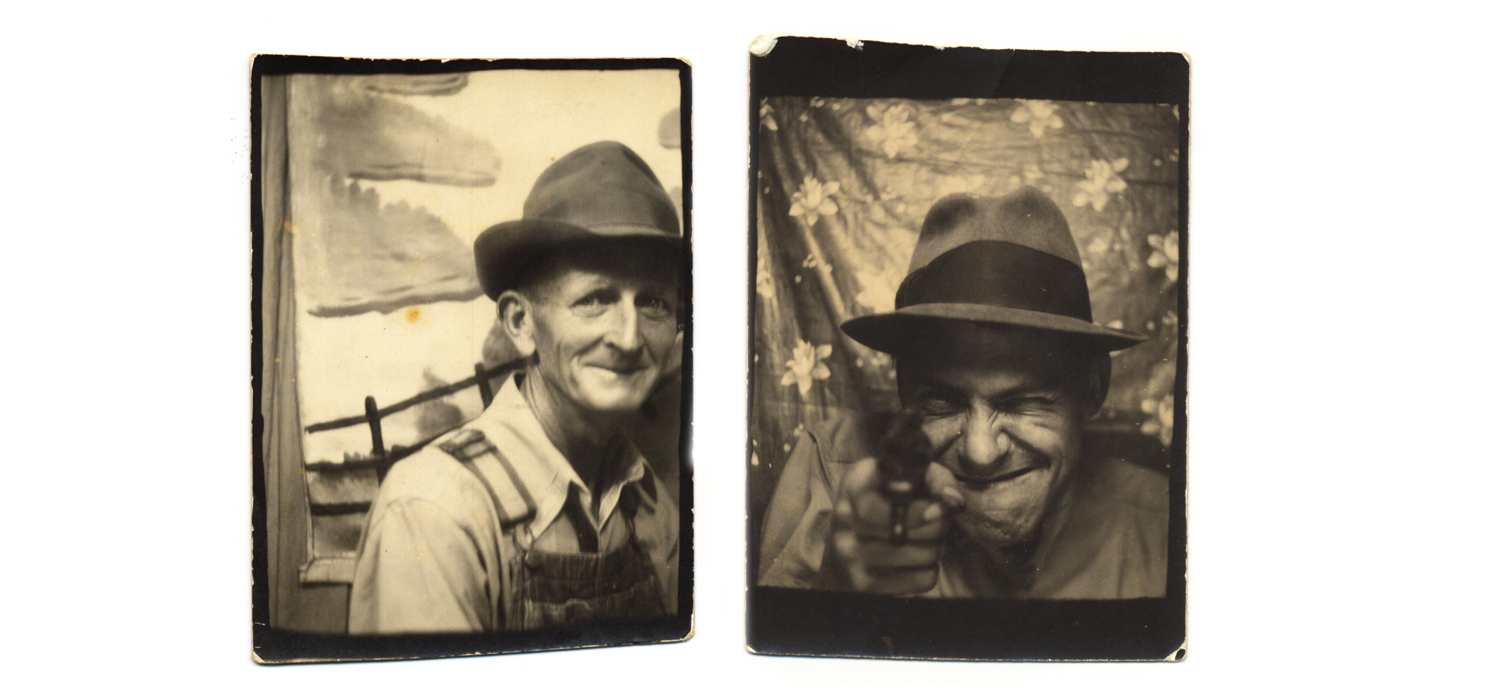

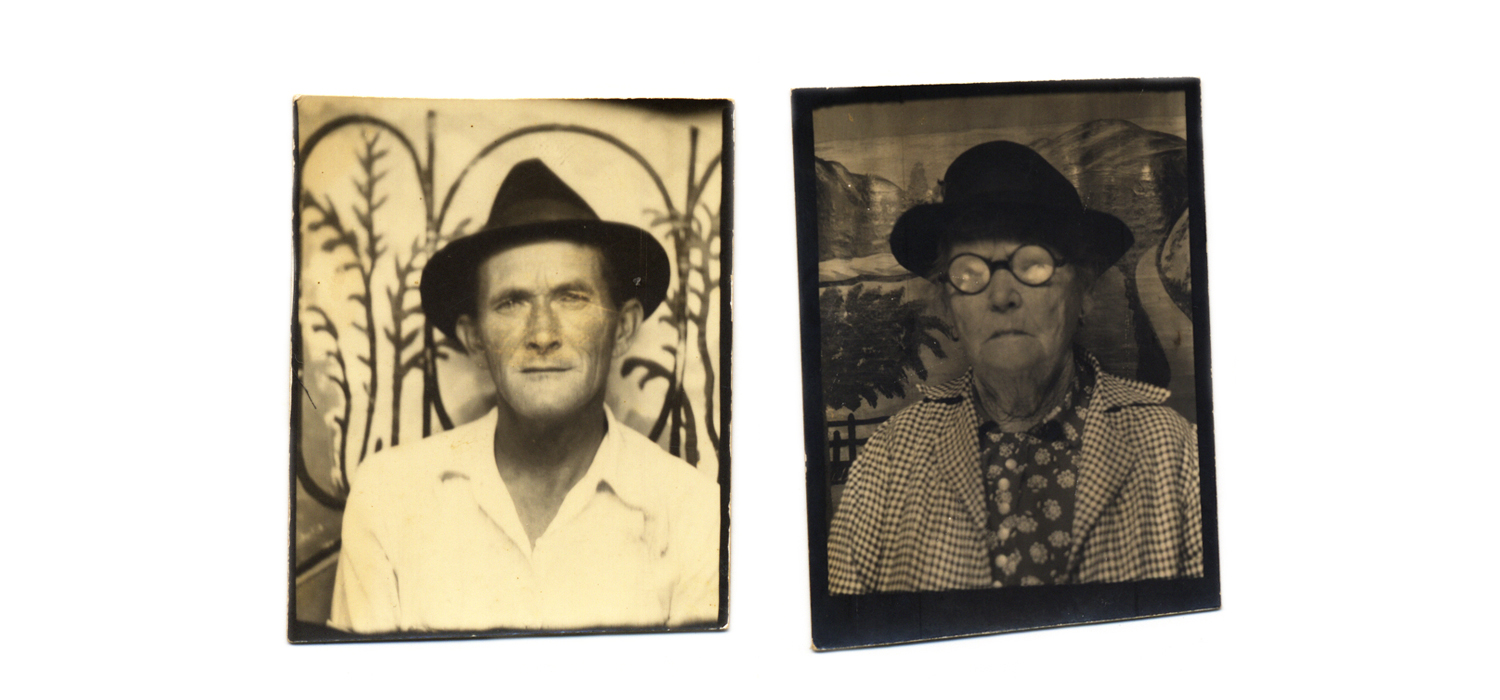

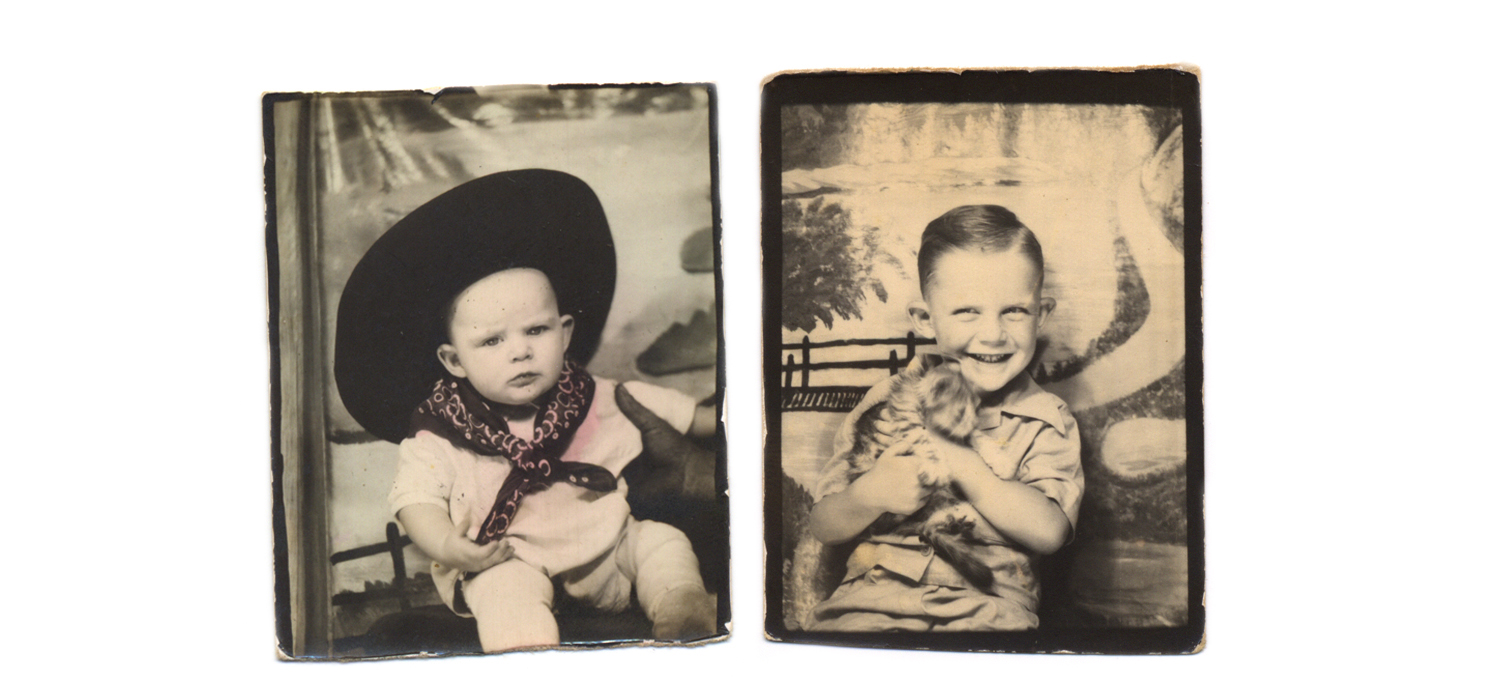

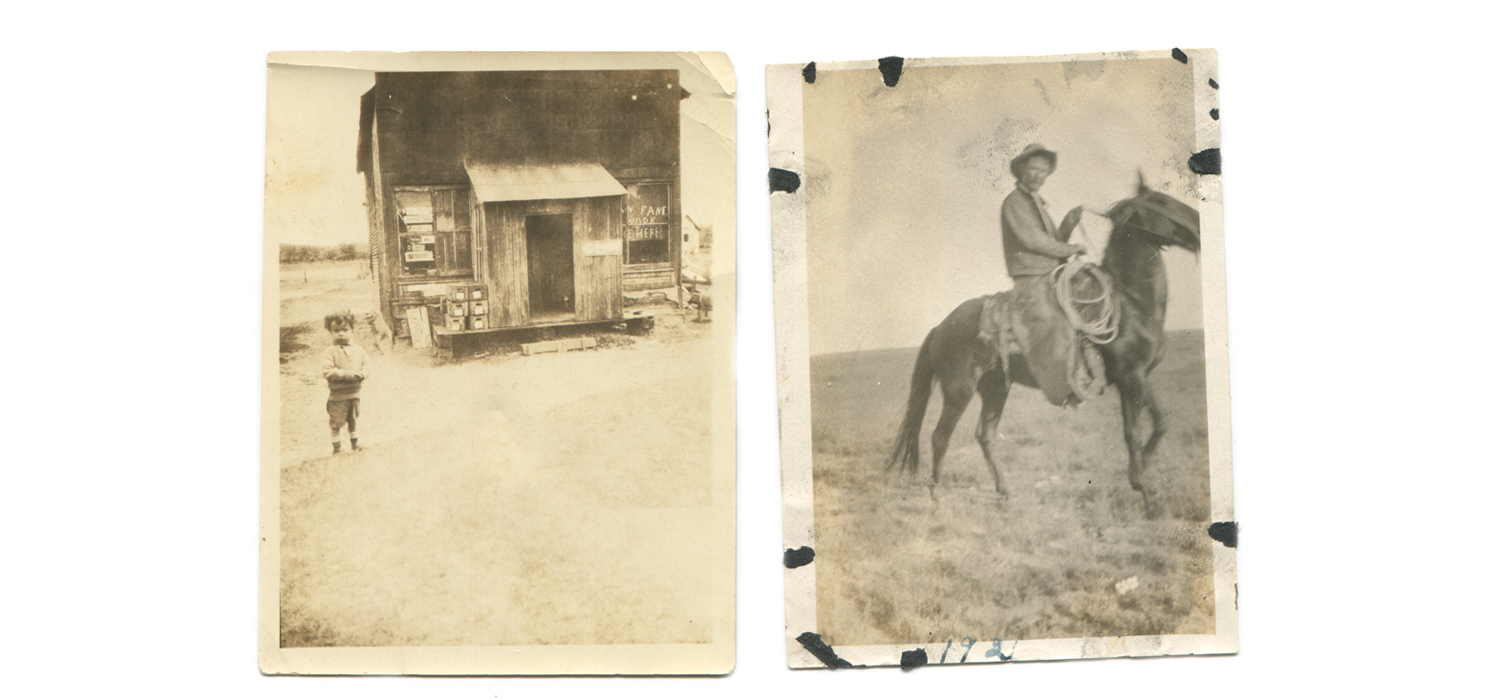

“Making Pictures: Three for a Dime” is a remarkable 180-page hardcover book with 271 images collected by the descendents of an Arkansas family that made its living by pulling a trailer with a photo booth mounted on it around their home state, offering the rural folks of Arkansas a chance to get their pictures made, three for a dime. You can also buy the book’s “soundtrack,” a CD called “Arkansas at 78 RPM: Corn Dodgers and Hoss Hair Pullers” that collects 26 recordings, made between 1928 and 1937 by bands with names like Luke Highnight & His Ozark Strutters or the Arkansas Barefoot Boys.

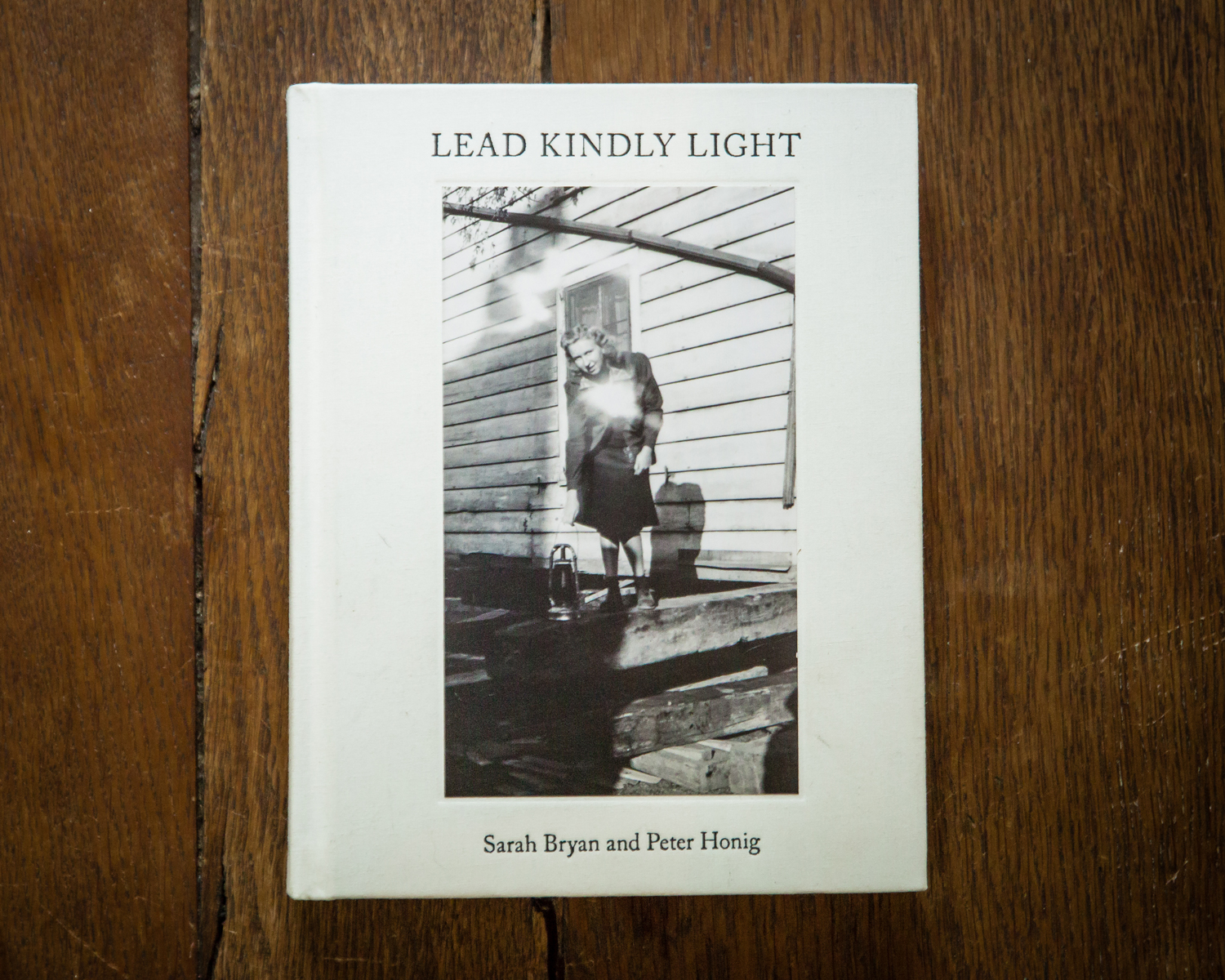

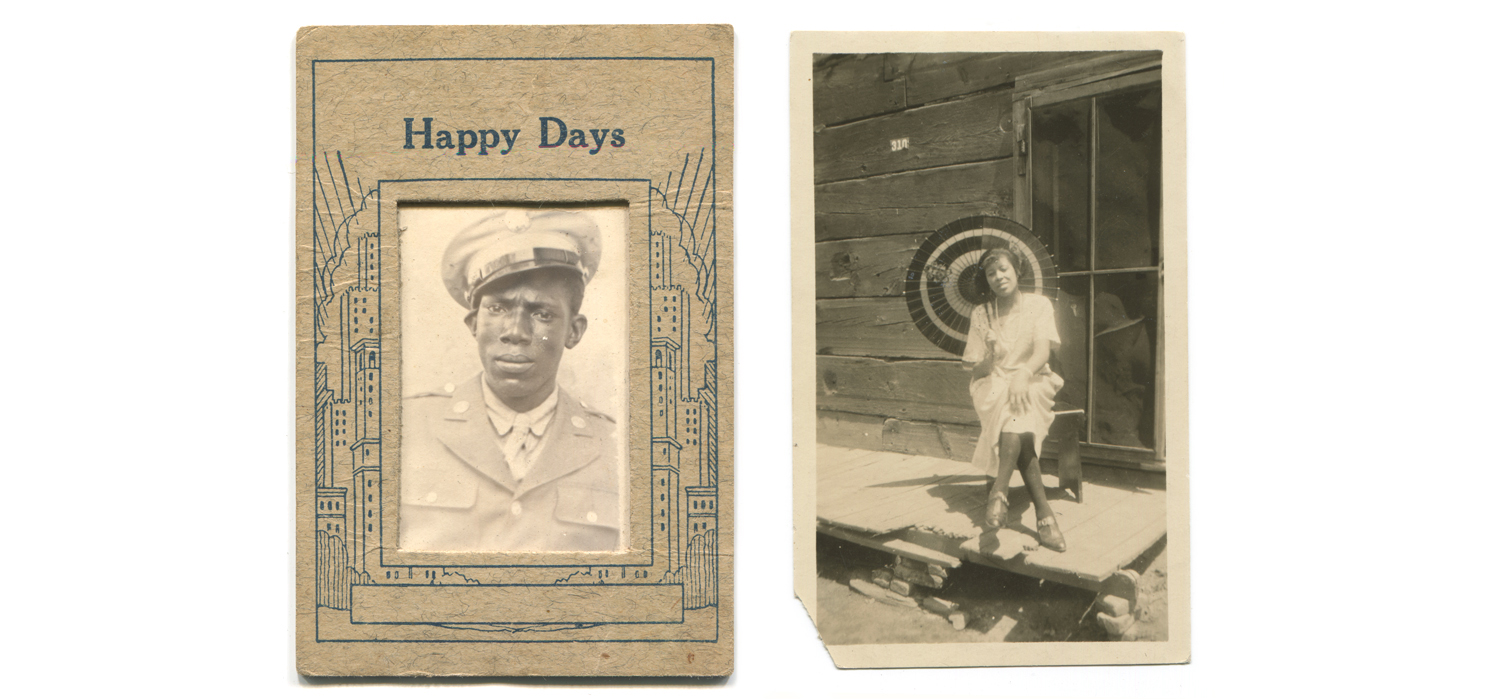

“Lead Kindly Light,” a 176-page hardcover book that pairs 159 photographs from the collection of Sarah Bryan, who edits the North Carolina-based Old-Time Herald, a magazine covering old-time Appalachian string-band music, with 46 songs from the vast collection of 78s owned by Bryan’s husband, Peter Honig, covering string-band, country blues and African-American gospel singing from 1924 to 1939.

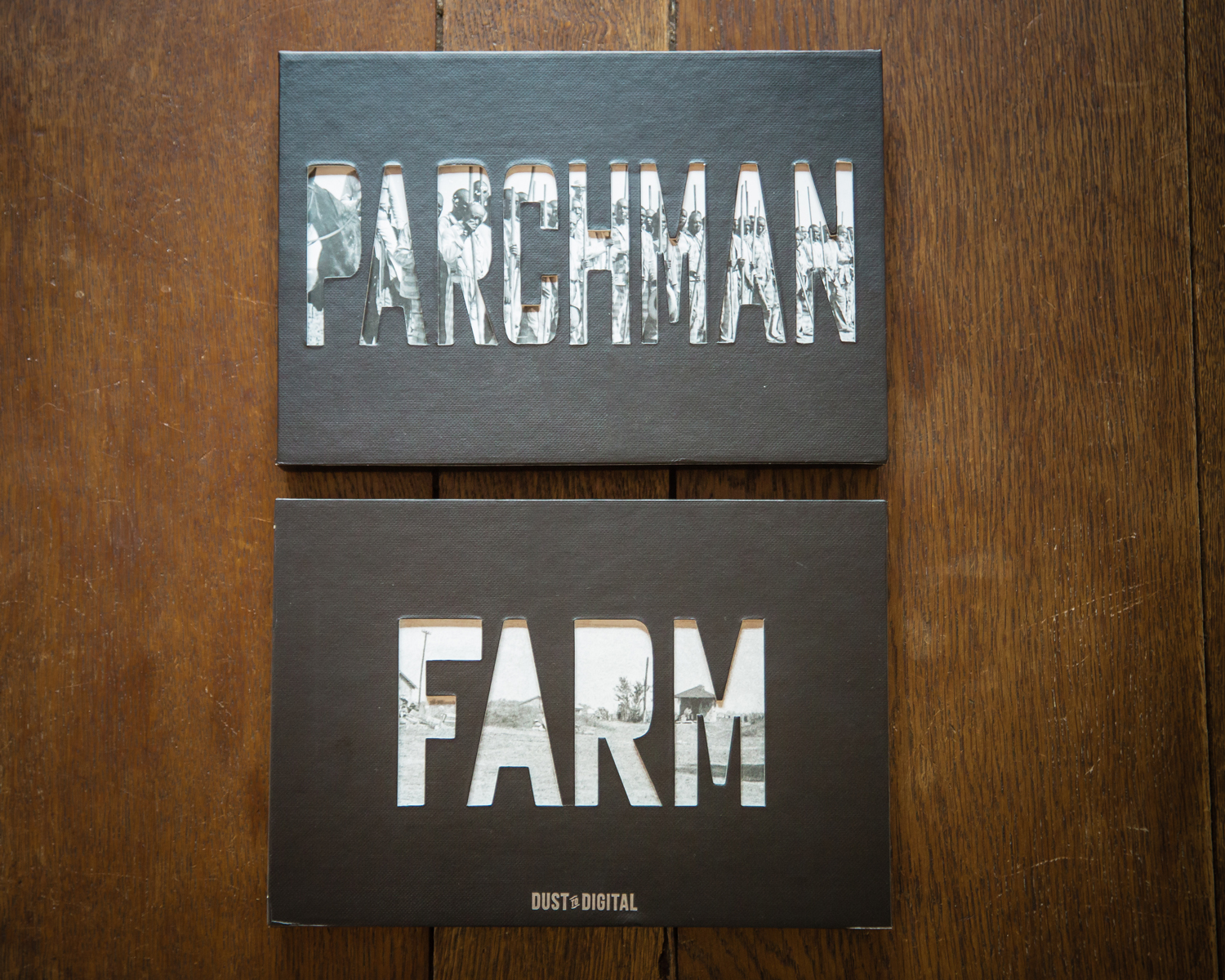

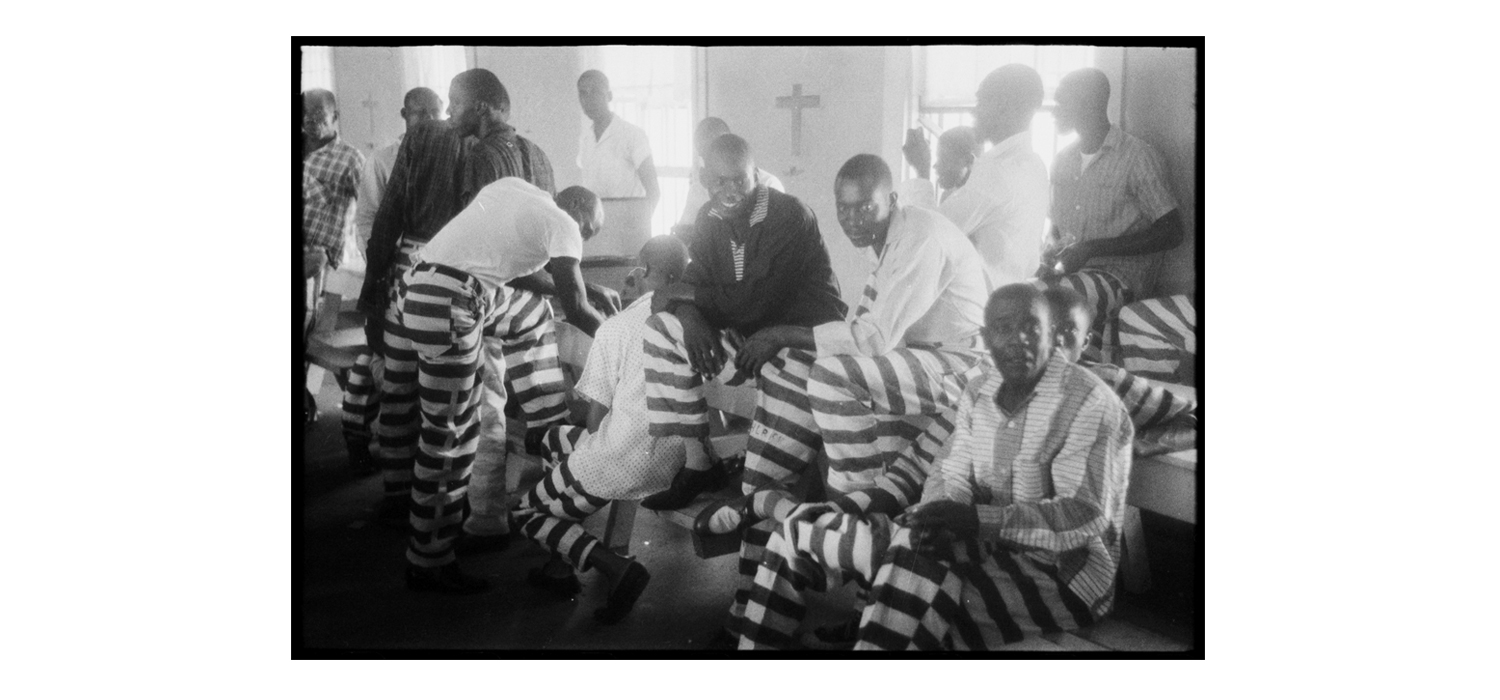

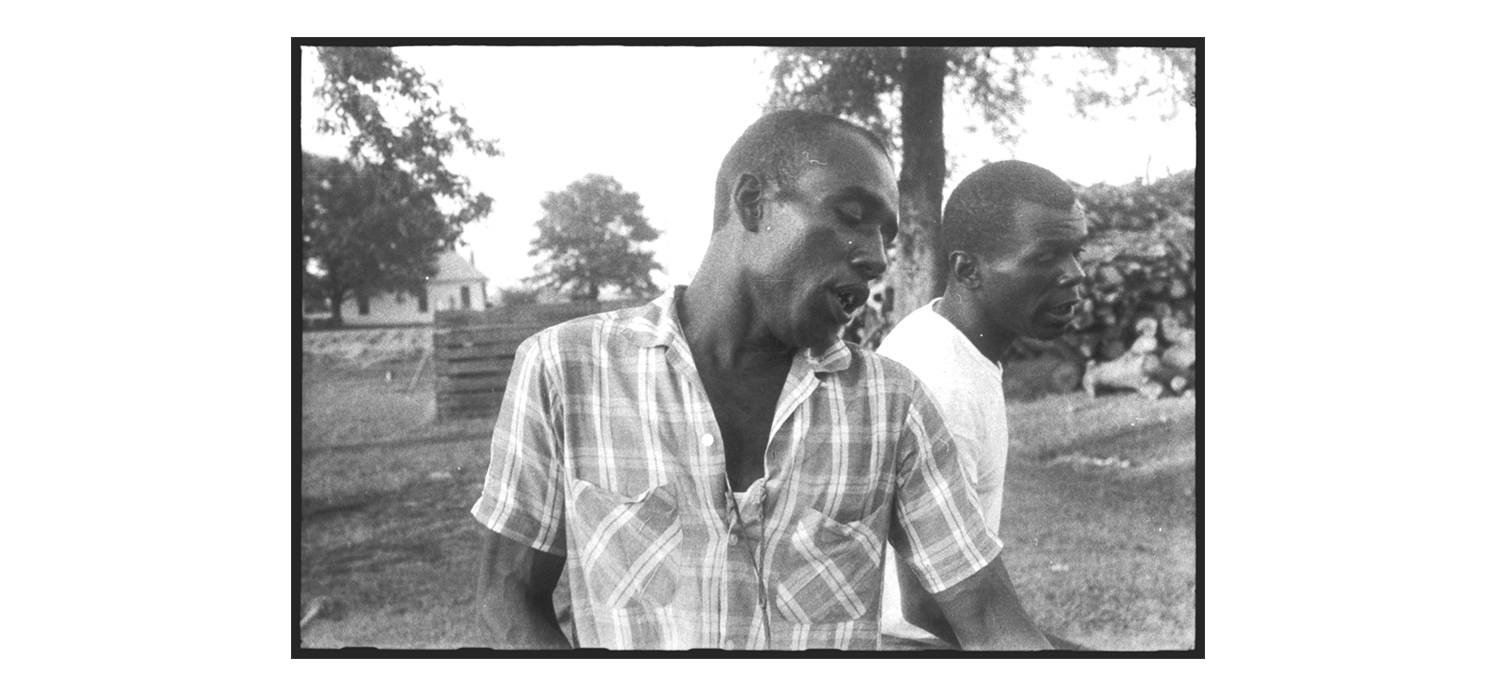

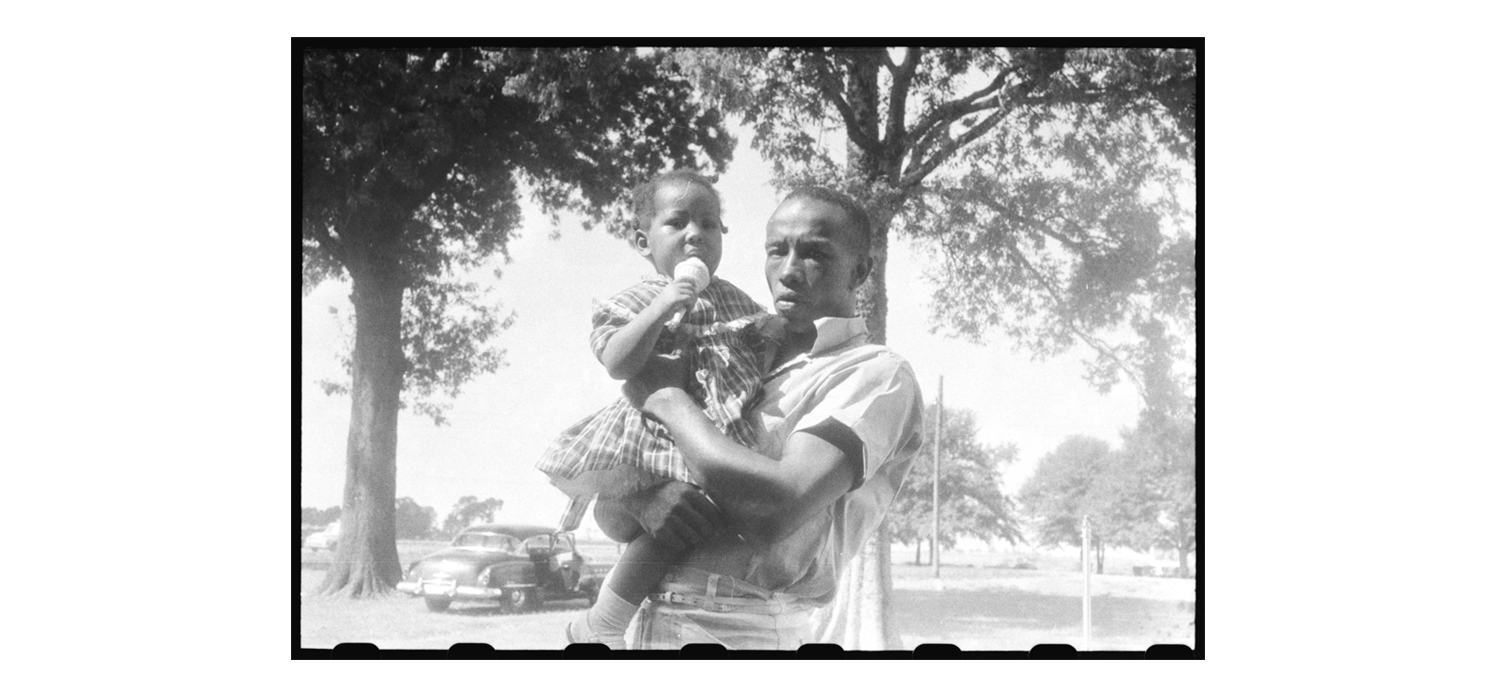

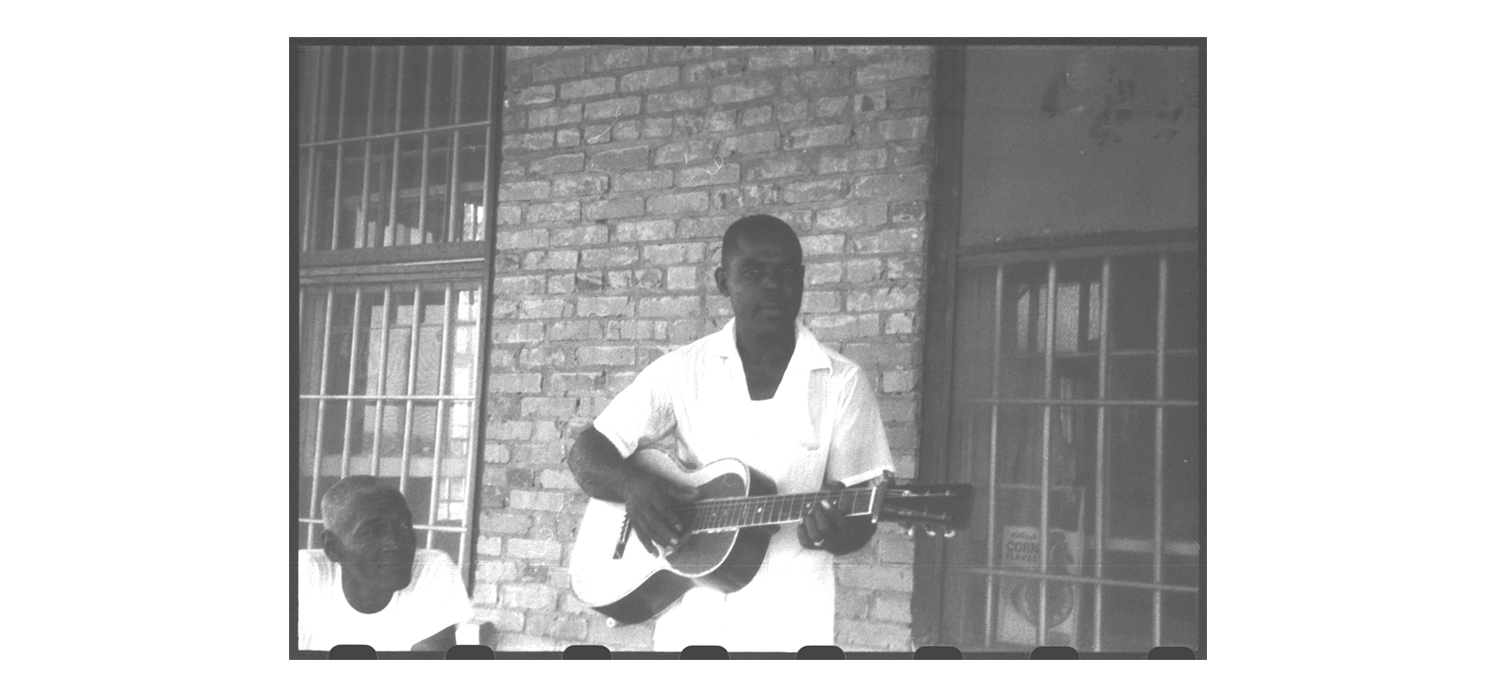

And finally, a beautiful but chilling package called “Parchman Farm: Photographs and Field Recordings, 1947-1959” that reminds us with astonishing clarity that slavery didn’t die with the Emancipation Proclamation but persisted deep into the 20th century in another guise: chain-gang labor.

From the almost breezy memories captured in “Making Pictures” to the bitter truths presented with no adornment on “Parchman Farm,” these three Dust-to-Digital releases remind us we live in a region that can produce moments of rare and wondrous beauty, even as we wrestle with our ignoble past.

The story of Dust-to-Digital has been told many times over by media far larger than The Bitter Southerner, including a fantastic 2008 piece in The New Yorker by Burkhard Bilger.

But it’s worth spending a little time re-examining how the little basement label first came to the world’s attention 10 years ago — and the effect that had on the lives of Lance and April Ledbetter.

After high school in the small northwest Georgia town of Lafayette, Lance headed to a little northeast Georgia college called Young Harris, which was then a two-year institution. His interest in old-time Appalachian music blossomed there after several visits to the John C. Campbell Folk School, just a half-hour up the road in Brasstown, N.C.

After he transferred to Georgia State University, the giant state school in the middle of downtown Atlanta, he met April Gambill, a Hendersonville, N.C., native who was studying film at GSU. The year was 1999.

“Lance was in my film classes, which was weird because he wasn’t studying film,” April says, sitting across the coffee table from her husband in the living room of their home, upstairs from Dust-to-Digital’s basement HQ. If you walk in their front door expecting to see the accumulated detritus of the obsessive collector, you will be shocked. Downstairs, the tiny warehouse/office is stacked with records and CDs, but those are either inventory or source material. Up here, there is only one neat wall of built-in shelves containing records — the cream of the crop of a collection that is now almost 20 years in the making.

By the time Lance met April, he was already deep into the obsession that would give birth to Dust-to-Digital. Two years earlier, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings had released — for the first time ever on CDs — Harry Smith’s “Anthology of American Folk Music.” The set had originally been released in 1952 in a set of six vinyl records. Perhaps the best short description of the set I’ve seen came from Bilger's 2008 story:

The anthology was divided into three double albums, each illustrated with mystical drawings, and color-coded blue, red, or green, to represent air, fire, and water. The real mysteries, though, lay in the music. Using crackly transfers from his own collection, Smith pulled together every kind of ballad, work song, parlor tune, and Cajun chanson. There were moaning blues by Blind Lemon Jefferson, hair-raising gospel by the Alabama Sacred Harp Singers, and anarchic banjo numbers by Dock Boggs — the sound and spirit of a forgotten world.

The set had a huge influence on a certain cohort of young Americans in the 1950s. By the early 1960s, it was the rosetta stone for every would-be beatnik poet and folk singer in Greenwich Village. It was not by coincidence that Bob Dylan’s first album, in 1962, included his version of “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean,” the 1928 original of which, by the Texas blues singer Blind Lemon Jefferson, appeared on Smith’s anthology.

But by the time Smithsonian Folkways finally released “Anthology” on CD in 1997, 45 years after the original release on vinyl, its scratchy old tunes represented completely unknown territory to a young student like Lance, who was coming up in the era of DIY punk bands and the heyday of college radio. Ledbetter had recently agreed to take over the GSU student radio station’s weekly show of music from the 1920s and ’30s when “Anthology” was reissued on CD.

“One of my friends had worked at WREK (the Georgia Tech student station),” Ledbetter says. “He got the hookup to get discount sets from Smithsonian Folkways. I met him at night in the WREK parking lot. They were in his trunk. It was like we were doing a drug deal or something. We got them for 40 bucks apiece.

“I was living in Decatur so I brought it back to Decatur,” he says. “I was by myself. I cracked it open. I couldn’t believe it. That was like the Big Bang for me. What happened that night was all the old-time music I grew up with as a kid in LaFayette, all the stuff I was exposed to at the John C. Campbell Folk School, all that stuff was just connected for me. I was like, ‘Well this is a whole new world of music.’ That’s when I realized that those six albums were just barely scratching the surface. There were so many rare great records. Even Harry Smith said in interviews that those weren’t the best records. They were just the ones he wanted to put in there because they needed to be documented, but there were a lot of great ones that weren’t on there. And he was right about that.”

Lance started searching for music from the old, weird America anywhere he could find it. At the time, it was mostly from cassette tapes in record-store bargain bins.

“I was just in mass consumption mode,” he says. “At that point in time, as the radio show kept getting better, I kept getting people calling in. I was connecting with people that way and learning about music. The show came on Sunday mornings from 9 to 11. In the South on Sunday morning, a lot of people are either going to church or coming back from church. I was constantly getting requests for gospel. But that was the one genre that I could not find.”

Thus began the obsession that would a few years later produce “Goodbye, Babylon,” Dust-to-Digital’s first product. The obsession could have ended his relationship with April.

“Really soon after we started dating was when Lance started talking about working on ‘Goodbye, Babylon,’” April says. “He was like, ‘I’m going to be really busy and doing all this stuff. I might not have a lot of time to hang out.’ I was like, ‘Is he trying to break up with me? What’s going on?’ I told him, ‘Why don’t you let me help you with that stuff?’”

Thus did Lance Ledbetter and April Gambill become the Frodo Baggins and Samwise Gamgee of the quest to unearth the roots of Southern gospel music — and that quest ruled their lives for the first four years of their relationship. Not long after their adventure began, they found their very own Gandalf the Grey in the form of a Baltimore record collector named Joe Bussard.

In the community of folks obsessed with collecting the earliest artifacts of recorded music, Joe Bussard is legendary. As another collector was quoted in Bilger’s New Yorker piece: “Bussard’s got shit that God don’t have.”

Lance and April’s research was turning up the names of old gospel recordings, but actually finding the recordings was a different matter.

“You couldn’t walk in a record shop and find any of this,” Lance says. “It was driving me crazy.” He did, however, find a few compilations of old-time music that shared a common component.

“A lot of them would say ‘original records from the collection of …,’ and the one name I kept seeing over and over again was Joe Bussard. I was like, ‘Who is this Joe Bussard guy?’ I found a phone number and called Joe,” Lance says. “The first time I talked to him, I think I maybe said two sentences. He talked to me for an hour about how I didn’t know anything about music. I was like, ‘OK, but I need some gospel music for my show.’ He was like, ‘Kid, I’ll send you down the catalog. You pick it out. I’ll make you cassette tapes for 50 cents a song. We’ll work from there.’”

Bussard actually made Lance and April pay him just to send the catalog. When it arrived in the mail, what they found inside it was a revelation. For instance, Lance possessed only one recording by the Atlanta Rev. J.M. Gates, although the preacher had recorded more than 200 gospel songs and sermons between 1926 and 1941.

“Joe’s catalog had six or seven 8½ by 11 pages of nothing but J.M. Gates songs,” Lance says.

“The titles for so many of them were so intriguing,” April adds. Amen to that: Gates’ first big-selling song was called "Death's Black Train Is Coming."

Says Lance: “I just started going through the catalog and writing things down. ‘This sounds interesting. That sounds interesting.’ And I’d send out the order to Maryland. I really started to learn a lot about the music and different styles. It was just such a fun adventure.”

Their original plan for “Goodbye, Babylon” was to issue a single CD of Southern gospel music with notes based on Lance’s interviews with various musicologists and historians.

“It started off as just doing a single CD,” Lance says. “But I started just falling in love with so many of these tracks. I was like, ‘I can’t cut that one…’ Then I said double CD. Then a triple. Then it got to the point where I had over 300 songs. Then I was like, ‘We got to start whittling.’ I whittled it down to 160. That’s what the final track count was.”

The final package contained five CDs with 135 gospel songs recorded between 1902 and 1960, plus one CD featuring 25 sermons recorded between ’26 and ’41. But that wasn’t enough. Lance and April also created an accompanying 200-page book with Bible verses, complete lyric transcriptions, and extensive notes about each recording. Then they had 1,000 custom cedar boxes made — 12 by 9½ by 2 inches — into which they hand-packed the CDs and book for each set. And just so everyone would know where the thing came from, they nestled the box's contents in bolls of raw cotton. Then they put it on sale for $109.95 a copy. The official release date was Oct. 27, 2003. A month later, on Nov. 30, The New York Times music critic Kelefa Sanneh published his review of “Goodbye, Babylon”:

Perhaps the season's most astonishing boxed set: six discs of gospel music and sermons from the first half of the 20th century, plus a 200-page book (including a history and transcription of every song), packaged with cotton balls in a cedar box. Many of the great American singers turn up, from Mahalia Jackson to the Carter Family, but even more impressive are the scores of relatively unknown performers who set up shop at the crossroads of the sacred and the secular. The sixth disc compiles sermons, including ''That White Mule of Sin'' (1929) by the Rev. George Jones, a confounding mishmash of prayer and parody. The so-called reverend sounds more than a little like Captain Beefheart, and he ascends to absurd heights of incomprehensibility (''Saddle up the road every whichaway and every whichabout,'' he declaims) while Sister Jones offers an updated version of the Lord's Prayer: ''Our Father, who art in heaven / The white man owed me 10 dollars, and I didn't get but seven / Thy kingdom come, thy will be done / I took that or I wouldn't have got none / Amen.''

The effect of the review was like a dam breaking over Lance and April.

“It was chaos,” April says.

“It was chaos, yeah,” Lance says.

“It was total chaos,” April says. “We had an apartment that was 900 square feet. It was small. The boxes were delivered there on two pallets. You couldn’t move in our space. It was insane. We were just assembling and packing the boxes. We had to hand-assemble everything, then shrink-wrap them, put stickers on them, box them up, ship them out, and then make an invoice. That was when I was like ‘Well, I guess I’m going to start doing some bookkeeping so we can get paid.’”

Lance may be the obsessive visionary of the pair, but make no mistake, without April, we might not have Dust-to-Digital today. She’s the one who has always kept the little label on an even keel when the pair found themselves in rough seas.

“It was just crazy,” Lance says. “People were calling, calling, calling. I remember one day I was just exhausted. I was lying on the couch, taking a nap. The phone is ringing. I’m like, ‘Should I get it or not?’ I get up. It’s Entertainment Weekly. ‘We’re going to put your boxed set on our “Must List” this week.’ The phone rings again. David Fricke from Rolling Stone. ‘Hey, we’re putting it in the best reissues column.’ It was insane.”

All this happened shortly after Lance had been laid off from the full-time job he’d landed after college, so April was working two jobs at the time — one at a hotel and one at a pizza joint.

Says April: “When the checks started rolling in from the distributors, that’s when Lance was like, ‘We can start paying you. You can quit those jobs if you want to work. Do Dust-to-Digital all the time.’ I was like, of course. Who doesn’t like doing their own thing all the time even though we’re busting our humps pretty hard?”

By the end of four months, they had sold all 1,000 copies, and its sales have climbed far higher than that over the years. After 11 years on the market, “Goodbye, Babylon” remains Dust-to-Digital’s steadiest seller. The price has dropped to a flat $100 now, but you can be assured that if you buy a copy today, it will still be hand-assembled by Lance and April in a little basement in Ormewood Park.

Cotton bolls and all.

William R. Ferris is perhaps the pre-eminent living scholar of Southern culture.

These days, he is the Joel R. Williamson Eminent Professor of History at the University of North Carolina and senior associate director of UNC’s Center for the Study of the American South. Earlier in his career, Ferris was the founding director of Ole Miss’ Center for the Study of Southern Culture, which begat the Southern Foodways Alliance. Ferris was also chairman of the National Endowment of the Arts under President Bill Clinton.

For short, let’s just say he’s a Mississippi boy who knows a thing or two.

Ferris says he thinks it’s appropriate that after 11 years of chasing, finding and recontextualizing folk music from all over the world, the Ledbetters have turned their attention once again to their native South with their three latest releases.

“I think Dust-to-Digital and Lance and April Ledbetter represent a very important new chapter in documenting the American South’s music and culture,” says Ferris, who is collaborating with the Ledbetters on a project the label plans to release next year. “I love to talk about sense of place as a force that defines the literary and musical voices of the region. I think the fact that Dust-to-Digital is located in the South means they are grounded in the region. Until them, all the great historical Southern recordings were released by the Library of Congress or record companies in Germany or Japan. Wherever music carries them, (Lance and April) go, but the foundation of what they do is the American South.”

The Ledbetters correctly point out that their musical interests spread out all over the world, and they have always been careful that Dust-to-Digital never be “pigeonholed as only being interested in the South,” April says.

But it’s hard to spend time with their three latest releases — “Making Pictures,” “Lead Kindly Light” and “Parchman Farm” — and not feel that the people who assembled these collections have an uncommonly deep understanding of their home region’s culture, its pleasant and ugly parts alike. These three sets will transport anyone who experiences them to different places in the South’s history — some of them as comforting and familiar as a hand-me-down quilt, others as dark and frightening as a Pentecostal preacher’s vision of hell.

“Making Pictures” is based on the lives of Lawrence and Thelma Bullard Massengill, who eked out a living during the Depression by mounting a photo booth on a trailer and pulling it all over rural Arkansas, offering people photographs at three for a dime. The project was born when Maxine Payne, a photographer and associate professor of art at Hendrix College in Conway, Ark., went home for the funeral of a grandparent.

“I was raised by my grandparents in a little town called Floral, Arkansas,” Payne says. “My grandparents died within a few months of each other, and when they did, there was a woman that came to the funeral who had grown up with my mother and around my grandparents. She said, ‘I have some photographs of your mom. If you're interested sometime and you want to come up and see them, I'd be happy for you to have them.’”

A couple of years later, Payne went to visit the woman, Sondra Massengill McElvey, at her home in Clarksdale, Ark. Together, they pored through bunches of photographs, although they found none of Payne’s mom.

“But I kept finding these little photographs that were like an inch by an inch and a quarter or something,” Payne says. “Hundreds of them. I just asked her what they were about and she said, ‘Well, yeah, my mom and dad, to make a little extra money during the Depression, made this homemade photo trailer and drove around the state making these pictures three for a dime.’”

Payne became fascinated with the pictures, and over the next five years she spent more time with McElvey and other members of the Massengill family, unearthing more of the three-for-a-dime pictures and, eventually, finding a diary kept by Lawrence and Thelma Massengill while they were on the road making photos from 1939 to 1941.

Payne wound up assembling the material into a set of large handmade books. But the material had no outlet to reach beyond Arkansas until Payne learned about Dust-to-Digital while she was teaching a photography workshop in 2012 at the renowned Penland School of Crafts in Spruce Pine, N.C.

“You know, you work with your nose to the grindstone for years and years and years and nothing ever good happens, right?” Payne says. “You just feel it’s all for nothing, and then you meet someone on a total fluke.”

The person she met was the Alabama fashion designer Natalie Chanin, who was teaching a workshop on sewing at Penland’s that same summer. Chanin put Payne in touch with the Louisiana-born photographer Phillip March Jones, who in turn connected her to the Ledbetters.

“When Maxine got in touch, she had made maybe five of these books,” Lance says. “I’m not kidding: They were maybe two feet wide and maybe a foot and a half high, handmade.”

Telling the story animates him, his hands flying about to convey just how impressive he found Payne’s handmade books.

“She sent us one of them,” Lance says. “It was just all hand-done, beautiful fonts and all the photos. You could tell this was very important to her. We saw all this. I think it was her commitment and her passion that sold me on the project. I was thinking, ‘OK, this is something extraordinary.’ She showed me where she was taking it, and I said, ‘OK, this is something that I think we can do.’

“We first talked about doing it as doing it without music,” Lance says. “I remember telling her, ‘I’m guessing we’re not going to include any music?’”

To put the set out minus music would have marked the first time Dust-to-Digital had cast itself purely as book publisher.

“But she said,” Lance recalls, “‘Oh, no. I hope we do. Music really needs to be there.’”

So Lance and April dove back into the weird world of obsessive record collectors.

“I found this musicologist who was doing this research on musicians from Arkansas and he and I just started making a list,” Lance says. Oddly enough, the musicologist in question, Tony Russell, lives in England.

“He’s probably the expert on Southern country music from the ’20s and ’30s, but he’s from London and he lives in London. He’s come over here probably about 20-something times to study it,” Lance says. “Europeans appreciate our cultures — particularly our musical culture, it seems — more than we do.”

Russell contributed the liner notes for “Corn Dodgers & Hoss Hair Pullers: Arkansas at 78 RPM,” the separately sold CD that serves “kinda like a movie soundtrack,” in Lance’s words, for the “Making Pictures” book.

The soundtrack analogy is apt. The photographs in the “Making Pictures” book are mostly of anonymous people: They are, after all, the photographs that the Massengills kept when customers decided not to buy. But the music compiled by Russell and the Ledbetters seems to speak directly to the Depression-era world in which the Massengills traveled.

You hear the voices of Dr. Smith’s Champion Hoss Hair Pullers, led by country doctor Henry Harlin Smith of Calico Rock, Ark., singing lyrics that seem to describe perfectly the attitudes of poor Southerners in the Depression:

In the future if a good thing comes along my way

And it as usual passes by, I’m simply going to say

Just give me the leavings, when you get through

Just give me the leavings, and that will do.

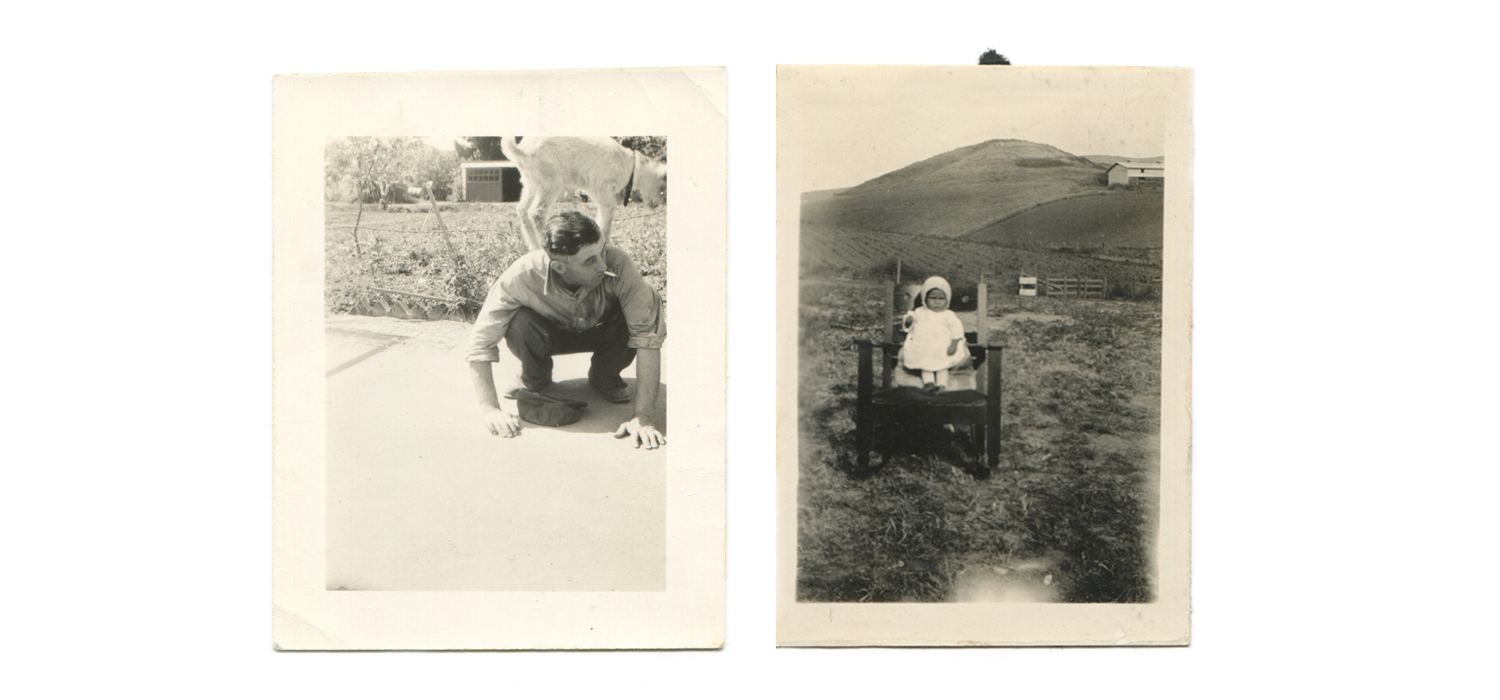

The photographs that make up “Lead Kindly Light” evoke similar feelings, but in an even more random way. The book, which includes two CDs of music from the same period, collects old Southern family photographs and snapshots from roughly the turn of the last century to the beginning of World War II. And we would never have seen them had it not been for another obsessive collector, Sarah Bryan, who lives in Chapel Hill, N.C., where she is the editor of The Old-Time Herald, a magazine for fans of old-time Appalachian music.

“I've always collected various stuff,” Bryan says. “I'd say I've been collecting photos in a serious way for probably 10 years or so. I'm a folklorist and most of my work involves field work, so I'm driving around mostly in Carolina. I started collecting photos seriously because I'd be going by a lot of antique and junk stores in small towns that I hadn't been to before. That always gave me an opportunity to browse and pick at photos.”

What makes Sarah’s collection oddly compelling is that pictures are from no particular family’s history, or from no particular place in the South. And every time she adds to the collection, she says, she is shocked to find photographs like these orphaned in junk shops. They are the leavings.

“That surprises me every time,” she says. “I can understand when they come from the estate of a person who's died and doesn't have descendants to give the family photos to. But I can't imagine, if there are still family members, I can't imagine letting these photos go. Oftentimes they have the person's name, if it's a portrait. They have the person's name written on the back. It makes me sad that they're not still with their family. I like being able to give them a home.”

These photographs cross many lines. They depict people both black and white, in settings rural and urban. To browse them is to see the South in cinema verite, exactly as it was, for better and worse, 75 to 100 years ago. Bryan has arranged the photographs in ways that emphasize their ordinariness. One photograph shows a man standing behind a waist-high stack of roofing shingles. On the reverse of the photograph, in an unidentified person’s handwriting, are the words, “Hear (sic) he is behind some shingles.”

Somehow, Bryan’s arrangement of the photographs prompts the viewer to see the similarities in the people instead of their differences.

Bryan’s husband, Peter Honig, chose the music to accompany the photographs from his own vast collection of 78s. His selections demonstrate how music also blurred the lines that separated the races in that period. Unlike us, our songs never seemed to have much trouble traveling back and forth across the lines that Jim Crow drew.

For instance, Honig includes a recording of “Mary Don’t You Weep” by the Georgia Yellow Hammers, a white string band from Calhoun, Ga. — a song that most people (including me) know only as a standard of black gospel, primarily from its definitive recording by West Virginia’s Swan Silvertones, a black quartet that recorded in the 1940s and ’50s. But the Yellow Hammers add a little Saturday night to the song's original Sunday morning sentiments: "The Georgia Yellow Hammers oughta be dead / Because they play all night and never go to bed."

The “Parchman Farm” set, on the other hand, paints far different — but just as accurate — pictures of the South in the middle 20th century.

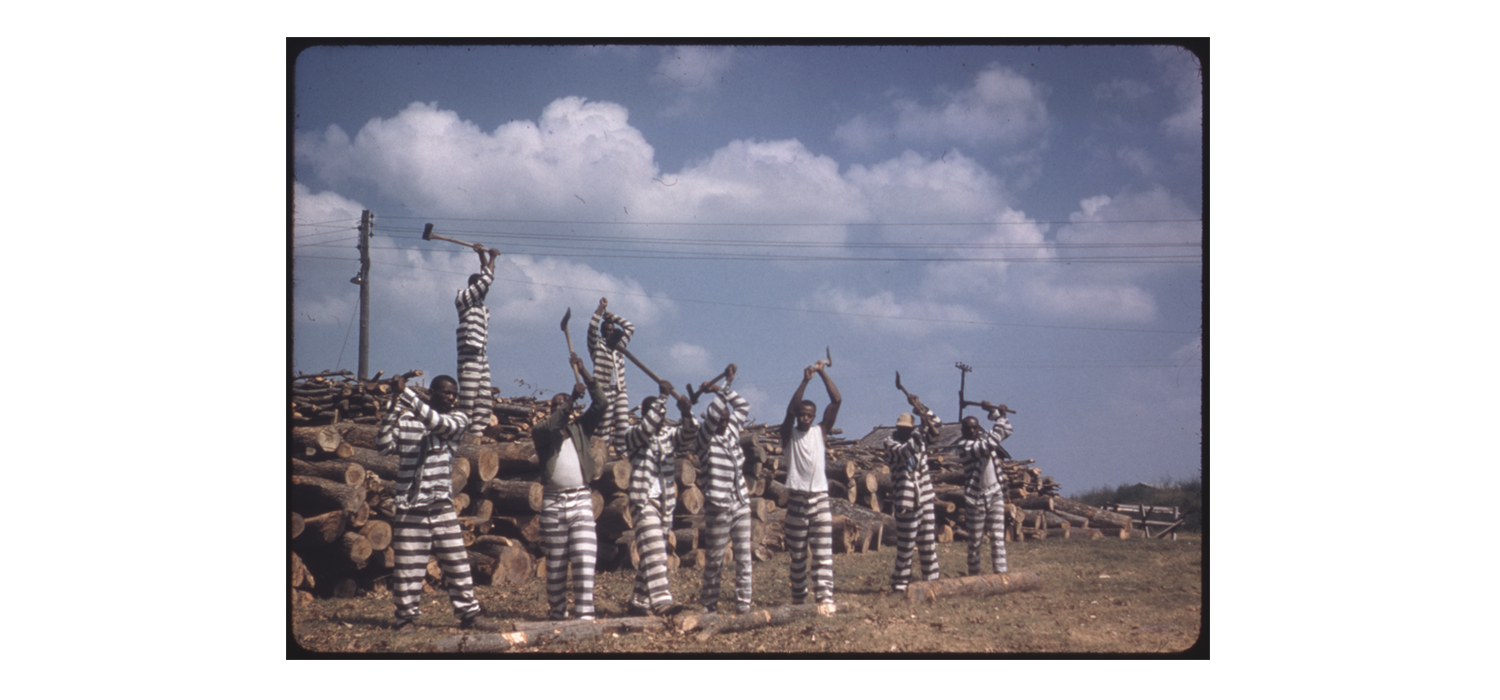

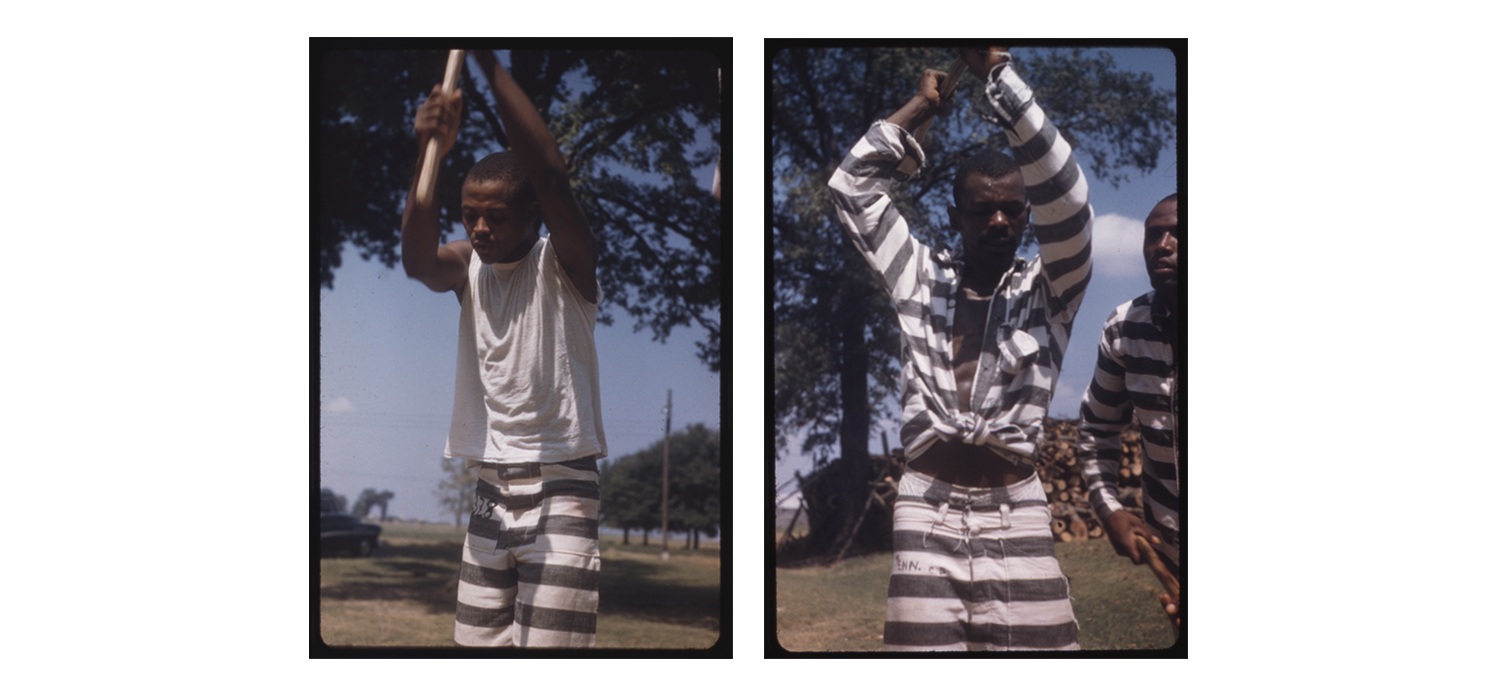

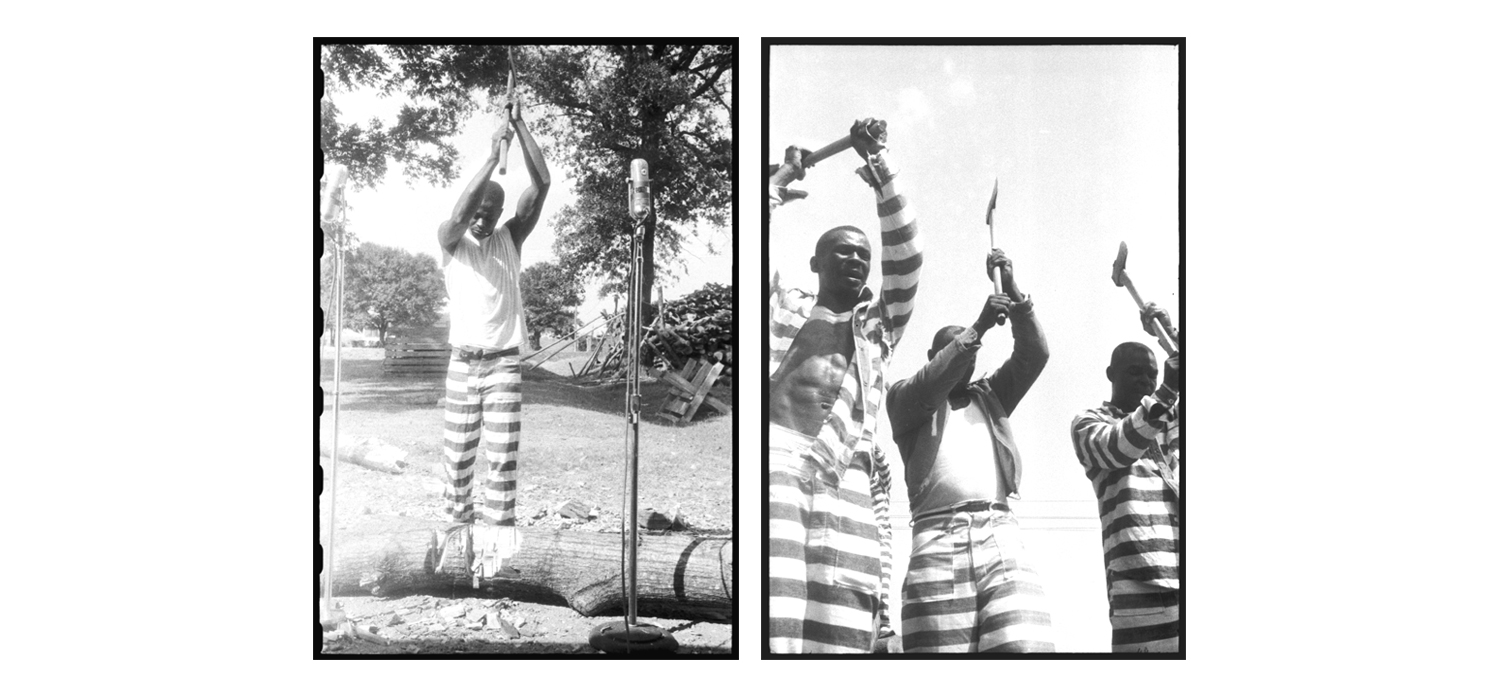

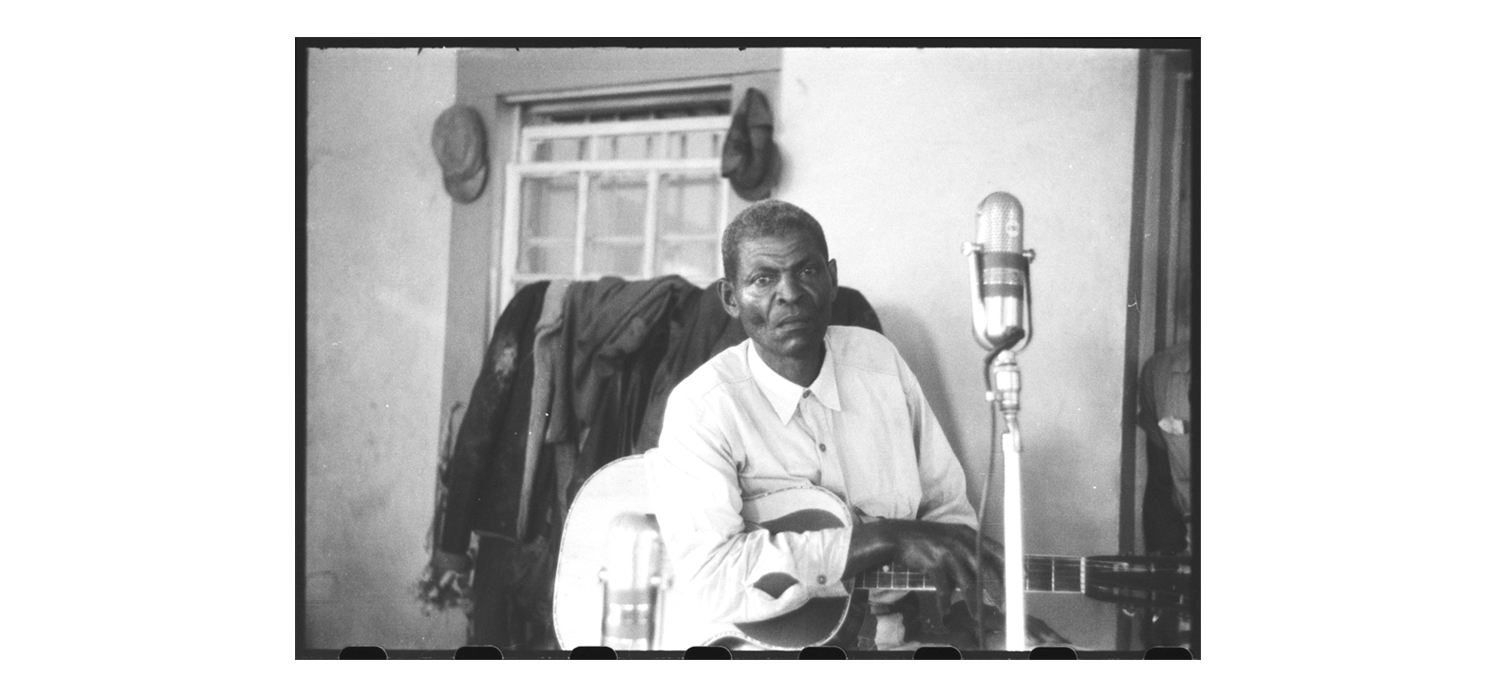

The set is the most complete collection ever released of the field recordings that the legendary musicologist Alan Lomax made at Mississippi’s notorious Parchman Farm penitentiary from 1947 to 1959. The set also includes a series of rich, striking, color photographs that Lomax made at Parchman in 1959.

“No one's ever linked the music to his photographs that he made in ’59 in the way that I thought should be done,” says Salsburg, who worked with the Ledbetters to assemble the project. Salsburg is the Kentucky-born curator of the Alan Lomax Archive, which is held by the Association for Cultural Equity, a New York-based nonprofit. “He took incredibly beautiful photos at Parchman Farm in 1959.”

In his introduction to the book that accompanies the set’s two CDs, Lomax writes:

“There was no Delta black who was not aware of how easy it was for him to find himself on the wrong side of those few strands of barbed wire. … My father, John A. Lomax, and I crossed these fragile prison barriers frequently during the ’30s and ’40s in our search for American folk songs. Because we were collecting for the Federal folk song archive, but, more especially, because we were Southerners, we were treated with courtesy and helped by the officials in charge. Yet we could not fail to see that most of the guards were untrained men, employed because they knew how to ‘handle and drive niggers.’ We saw with horror that there were sadists among them who took pleasure in persecuting, beating, and torturing the helpless prisoners. We did meet sincere, kindly men trying to better the lot of the prisoners, but they were hampered by the limitations of the institution itself. A report in the New York Post (January 7, 1957) confirms my own impression of a generation ago: ‘The state penitentiary system at Parchman is simply a cotton plantation using convicts as labor. The warden is not a penologist, but an experienced plantation manager. His annual report to the legislature is not of salvaged lives; it is a profit and loss statement, with the accent on profit.’”

Truly, the Southern chain gangs of the 20th century were, to borrow the title of Douglas Blackmon’s Pulitzer Prize-winning history, “slavery by another name.” Through them, Southern governments effectively kept the plantation system in place for a full century after the Emancipation Proclamation was supposed to have ended slavery. And throughout that century, our state and local governments kept their thinly disguised version of slavery fully supplied with labor by arresting African-American men for petty crimes and imposing fines those men could not pay — thus guaranteeing they would do time in Parchman or another place like it, where they would toil with no recompense for whichever local white businessman or farmer was paying for chain-gang labor.

It is one thing to read these facts in the carefully constructed words of the folklorist Lomax or the journalist Blackmon, both of them white Southerners struggling with the racial divides they abhorred. It is entirely another to hear the facts in the voices of the prisoners, the 20th century slaves, as they sing their work songs — and to see Lomax’s vivid color photographs of them.

On Dust-to-Digital’s “Parchman Farm,” you notice immediately a higher fidelity in the recordings. The scratch and hiss of old 78s is absent, because by the 1940s, the Lomaxes had state-of-the-art field-recording equipment. So when you listen to a song like “The Prettiest Train I Ever Saw,” recorded in 1947, you hear with shocking clarity the only non-vocal element of the song, the thing that keeps the rhythm: the sound of the prisoners’ hoes breaking into the Mississippi clay.

And you hear their harmonious voices, telling us — with oblique but precisely pointed lyrics — that they knew exactly what game was being played at their expense.

Prettiest woman that I ever seen

Rampart Street in New Orleans

You go to Jackson just to show your clothes

I go to Jackson, play them dicin’ holes

When you go to Memphis don’t you hang around

Police’ll catch you and you workhouse bound.

And finally, you hold the book in your hand, and you see that Lomax was meticulous in his documentation. “The Prettiest Train” is credited to prisoner No. 22, “Benny Will Richardson and group: vocals and hoes.”

Today, if you want to hit them dicin’ holes, you get in the car and head over to Tunica or up to Cherokee to the casino. Unless you’re a complete fool, you don’t have to worry anymore about a little craps game landing you in the workhouse.

That’s why this particular boxed set from Dust-to-Digital matters so much. You hold it in your hand. You read the stories. You listen. And it puts you there, inside Parchman Farm, in 1947.

It’s a place where every Southerner needs to go, so that we learn never to go back there again.

“What they do …”

Bill Ferris pauses a bit, trying to come up with the right words to describe what makes Dust-to-Digital special.

“They don’t simply reissue recordings,” he finally continues. “They create an environment within the confines of a box. You have the music, but you may also may have a book, or pieces of cotton plants. They make very imaginative uses of art to frame and amplify the music, and they do it with a design sense that’s on the cutting edge. They’re creating multimedia work of arts. It pushes the envelope of what music and recordings can be. They, in tandem with people like T-Bone Burnett (the producer of the soundtrack to ‘O Brother, Where Art Thou?’ and many other updates of American folk music), are taking Southern music to places that were unimaginable in an earlier period.”

There may be no organization in the world today that has greater capability to capture the elusive musical and visual past of the South than Dust-to-Digital. Lance and April are both excited about the new potential they’re seeing, particularly through projects such as “Making Pictures” and “Lead Kindly Light,” to use photographs to paint fuller, more well rounded pictures of folk music and the people who made it.

“Maybe what it is, is that people are looking for ways to have context for their lives,” April says. “Getting to see something like these sets, you might imagine that this is what it was like in your family, for your grandparents or great-grandparents.”

Lance picks up the theme and continues. “It’s like building blocks,” he says. “With ‘Goodbye, Babylon’ and our other sets that are more musically driven, the people I hear from talk about how these are building blocks for musicians — guitar phrasings or lyrical ideas they can put in their repertoire. But in these three releases this fall, the photographs are sharing the stage. It’s wider ranging than just the building blocks of music. It’s like the building blocks of our lives. Where do we come from? What were these people like? How long ago was this? Where are we now? How have things changed? This is in your hand, and you’re basically having to face your own thoughts.”

In certain Dust-to-Digital releases, that experience can be comforting, “like walking into a house you’ve already known,” as Lance puts it. In others, the experience is about harder truths.

Lance looks at me across the lunch table one October Monday and says, “You know, you and I have the familiarity with what we grew up with — you know, us being free white people — and ‘Lead Kindly Light’ and ‘Making Pictures’ reflect that, but ‘Parchman Farm’ is a whole different thing. To me, when I first heard those recordings that Lomax had made, once I heard them, I could never unhear them. They were so powerful. I couldn’t believe how visceral it was. The high-fidelity sound quality was almost more chilling than if it had surface noise or scratches. You are more present in that place.”

But even in these shocking recordings, there is hope. It is important to remember that the power in those songs — forged though they were in strife and wrong — can always be turned to higher and better purposes by modern musicians. The scholar Ferris takes care to remind me what can happen when we hear this music of our past and absorb it.

“I think music is a model of how reconciliation can happen,” he says. “The history of Southern music is the history of the blending of these cultures — Indian, African and European. Western European instruments played by black musicians and bent into new sounds.

“Lance and April are young. They have a long and productive career that lies ahead. They will have a significant influence on the future of American music. The Duane Allmans and James Browns of the next generation will be able to come to Dust-to-Digital for the sacred texts — and build the next generation of our region’s music.

“Nothing,” Ferris concludes, “goes across racial barriers more easily than music.”