How a New England Boy Found Love in the Carolina Dirt

Story by Jodi Rhoden

Photography & Video by Whitney Ott & Jaemin Riley

East Fork Pottery is down past the Church of God at the tail end of Ras Grooms Road, along the east fork of Bull Creek in the lush, green mountains of Madison County, N.C.

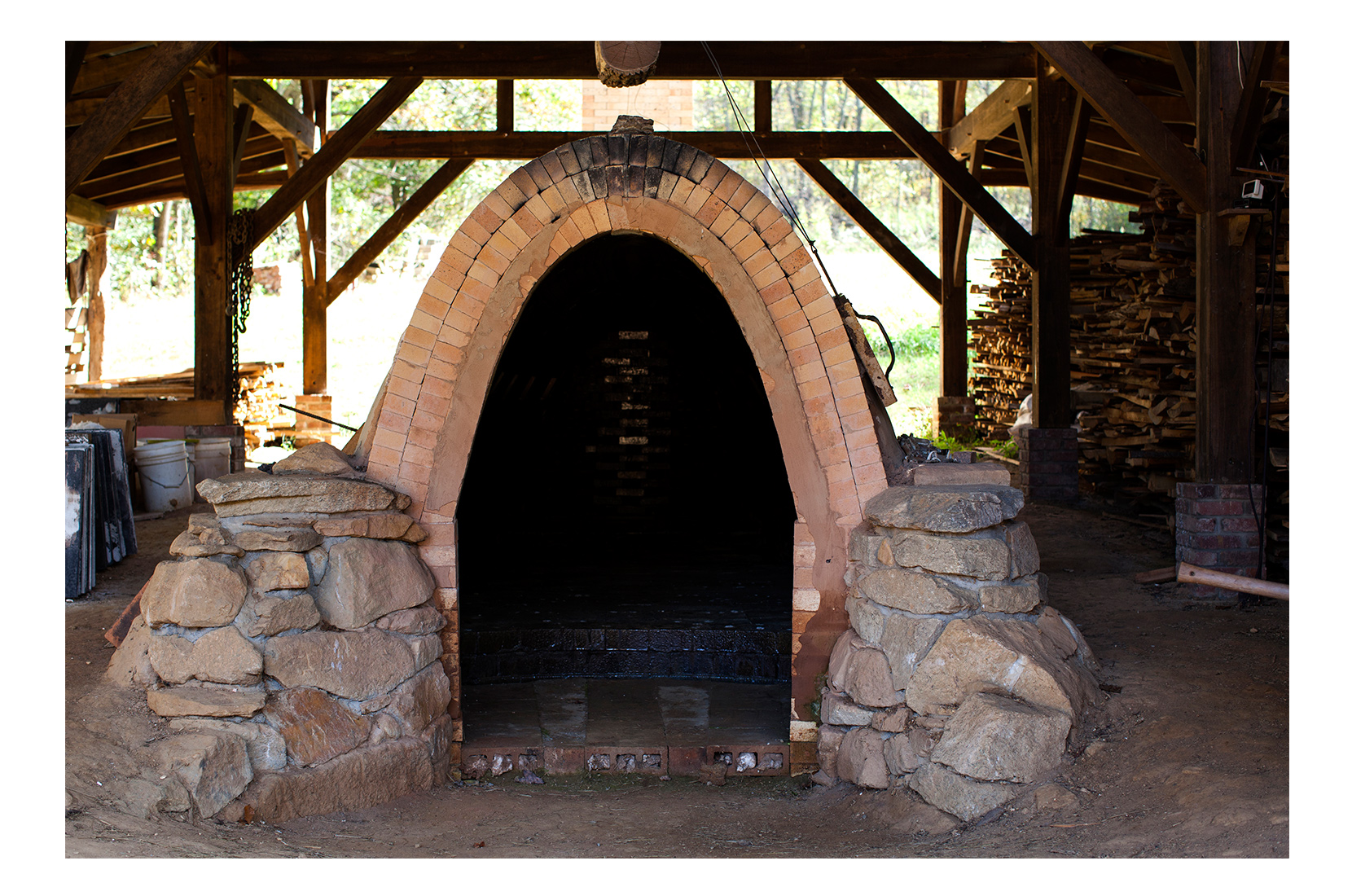

The dogs that live along this road have the habit of charging toward intruding vehicles, or else just lying down in the middle of the road when a car comes along so getting to the gravel road that leads to the pottery requires a slow and persistent approach. Once there, however, one is richly rewarded: You can see, nestled in the ravishingly beautiful open slope of the mountainside that once was a tobacco farm, a soaring timber-framed shed roof covering a massive wood-fired kiln, which rises from the earth like a giant mud-dauber’s nest. An old farmhouse and two pottery workshops sit stacked, floor to ceiling, with shelves full of pots in various states of completion.

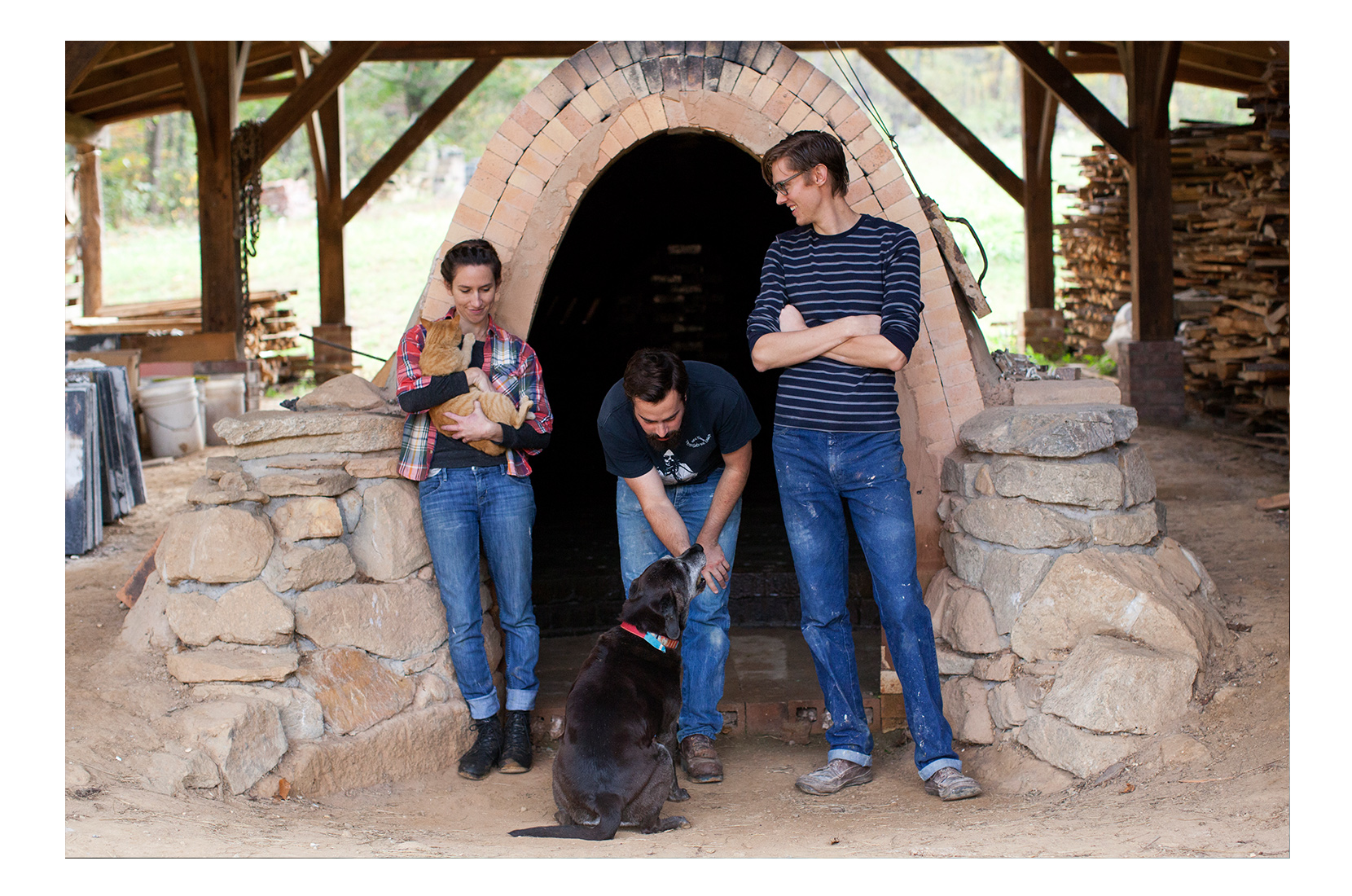

This cluster of buildings contains the entire body of work of East Fork Pottery, the labor of love of Alex Matisse and Connie Coady.

Completely Unfussy

The first day I visited East Fork was on a glorious morning in late September. It’s a 40-minute drive north of Asheville. When I arrived, Alex bounced out of the workshop door bright-eyed and already muddy from throwing pots, eager to show me around. He was dressed in jeans and a red flannel shirt, his hair short and dark beard thick. His eyes gleamed as he began to talk about his work. Connie, also in flannel and jeans, her head crowned with a simple braid, interjected commentary as Alex spoke, filling in details.

Connie and Alex told me, in their teamwork style, about the technical details of the pottery: the method and history of salt-glazing, the purpose behind “wadding” (the meticulous process of tacking wads of material to each pot to prevent it from sticking to the kiln shelves), the local sourcing of the waste-wood that is burned for fuel during the three intensive days of firing.

This is the method: Alex builds thousands of pots one by one, then dries and decorates them. He and Connie, along with a contingent of friends and fellow potters, seal them in the kiln and build a steady fire that reaches a stunning 2,300 degrees — literally hot enough to melt your grandma’s cast-iron skillet. They never know exactly how much of his work will be destroyed in this age-old process. Typically, 5 to 10 percent of the pots never make it out alive.

The pots that survive range from delicate, cream-colored espresso cups with soft, organic lines, to formidable urns standing outdoors year-round, with a riot of green, brown and gold glazes dripping luxuriously down the sides. Some of the work is more measured. There are chargers with precisely rendered shapes of moths circling their edges, forming star-shaped patterns in the negative space between them. Many are decorated with only simple, vine-like patterns of light-colored glaze. Many are speckled various shades of black and brown from the salt-glazing method, edged with mottled tinges of blackened glazes fading into reds and browns — like so many loaves of bread baked in a searing wood-fired oven.

The pots all seem eminently useful — bottles that ask to be drank from, vases that beg for flowers and coffee mugs that fit most comfortably in the palm of the hand. Many of the pots’ shapes tell stories of uses now obsolete, like the corked whiskey vessel which, rather than standing upright, was crafted to hang from a leather sling with the cork at the top, so that its user could simply take a pull to pour a shot and, once loosed, the vessel would return to its previous position. Alex’s pots — while beautiful to touch, hold and see — convey a deeper sense of sturdiness, precision and symmetry. They seem almost austere, in a way that hearkens back to their Colonial and pre-Colonial roots.

And to their maker. They’re not fussy, these pots, and the same could be said of Alex Matisse.

The New Englander Comes South

Born in 1984, Matisse grew up in an affluent family in a renovated clapboard church in the small town of Groton, Mass. He did what many affluent kids do. He wanted to prove he could build his own life, so he left Massachusetts to make his way, to find himself. His first stop was Guilford College, a small, liberal Quaker school in Greensboro, N.C.

There he took a pottery class with a guy named Charlie Tefft and was instantly smitten with the craft. More importantly, perhaps, he had serendipitously landed in the epicenter of American pottery culture.

He was surrounded by pots.

He discovered closed-form pots that had once been used to mark graves by those who couldn’t afford to buy headstones and grotesque face jugs and delicate teapots made from North Carolina clay in the Japanese Mingei folk tradition. He discovered potters building rivers of fire inside kilns full of pots, then blowing salt into those kilns to create glazes, and he discovered the stories of the the late potter Dave Drake from Edgefield, S.C. Born in the early 1800s, Drake was a slave who had been taught (illegally) to read and write and who painted poems in rhyming couplets on the sides of his pots.

Alex discovered the slow, steady process of alchemically melding earth and fire: of preparing clay, mixing glazes, throwing pots and firing them over three days with wood, using salt, wood ash and slip (water in which clay and/or other materials are suspended) to manipulate color and create designs. Alex discovered that in the South, unlike in his native New England, the tradition of making pots by hand remained an unbroken chain passed along, down through the generations, and that here — planted firmly in the soil that contains some of the richest, most abundant and most diverse seams of clay in the world — was a living, thriving lineage of art into which he threw himself, headlong.

Alex had fallen in love.

He soon dropped out of college to begin two years with North Carolina potter Matt Jones in one of the strictest versions of ceramics apprenticeship in the United States: learning to make not just one, but thousands of exact replications of his teachers’ work. This deep form of apprenticeship allowed him to absorb his teacher’s influences, worldviews and style, while embarking on what he calls his own “slow arc to find a voice.” After leaving Jones’ employ, he took another apprenticeship, this time with Mark Hewitt, a potter who had adopted North Carolina after growing up in Stoke-on-Trent, England, where his family managed the legendary Spode china factory. After a year with Hewitt, Alex, at the ripe old age of 25, was ready to build his own pottery.

Meanwhile, Connie Coady, a third-generation Los Angeleno, had left her adopted home of New York City at age 23 years old with the intention of taking a Peace Corps job in Venezuela. But first, she set out across the country on what she calls “kind of a self-searching trip.” Her searching led her, after a stop in Montana, to a temporary, 70-hour-a-week job at a goat dairy in Shelton Laurel, deep in the hills of Madison County, N.C. She never intended to stay, but it was there, while selling goat cheese at a holiday farmer’s market in Mars Hill, that she met Alex.

East Fork Comes to Life

The two moved together to the land outside of Marshall, which Alex had recently bought, that would become East Fork Pottery. For three years they lived in the ramshackle farmhouse while Connie tended bar at Table, a highly regarded restaurant in downtown Asheville. Together they built East Fork Pottery: the kiln, the workshops, the website — and most importantly, the relationships with their neighbors and community. Connie has turned East Fork’s kiln sales (timed to the quarterly firings) into big, festive, food-filled celebrations.

“Since food storage, preparation and presentation is and was why most pottery was made in the first place, it makes sense that we would find ways to showcase the pottery in its most natural setting: filled with good food and drink and passed around a table of friends, new and old,” she says. Connie grounds Alex’s work in the practical world. She uses his pottery as a vessel for her food and drink. And she makes their entire business greater than the sum of its parts. Being from Los Angeles by way of New York, Connie has brought a big-city vibe to a small-town craft. “I’m trying to encourage Alex to educate a new, younger, wider-reaching community about how owning fewer but better-made, humble, beautiful objects can enrich the tapestry of daily life in a substantial way,” Connie says.

For now, East Fork has settled into steady cycles of pottery production, firing, traveling to shows and hosting kiln sales. But ultimately, Alex and Connie hope to have a restaurant or event space in which Alex’s pots would hang from the walls, decorate the tables and contain the food and where the food and drink reflect the same thoughtfulness in sourcing and craftsmanship as the pottery — an extension of the conviviality shared at the kiln openings. As a step toward that, just last month Alex and Connie organized and hosted their first market dinner prepared by Table’s chef and owner, Jacob Sessoms, to launch East Fork’s new line of contemporary dinnerware. The menu paired a “Faulty Water apple cider, Calvados, lemon, sage and Prosecco” cocktail with chicken liver pate and shrimp toasts, among other delights, all served in ceramic vessels made by Alex. (The Faulty Water is a quite rare heirloom apple variety, and it grows at East Fork.)

Another recent and painstaking development at East Fork Pottery has been Alex’s creation of a totally new series of work, one which departs from his traditional wood-fired pots of the past: electric kiln-fired slip-cast ceramic hanging light fixtures. These thin globes of porcelain, slick and modern and hand-decorated by Alex with his own take on the traditional “sliptrail” style, create warm orbs of light when illuminated from within. The result of months of trial and error, the lights are a brilliant juxtaposition: delicate and airy creations made from a heavy, earthen material. The lights transcend traditional pottery, and they are deeply meaningful for Alex.

“There’s this theme that I struggle with of feeling often in the shadows of other people, especially given my family background,” Alex says. “These lights are the first thing that I’ve done that I’ve really felt like have been my own, in a big way.” You can feel that when you see them. They are strikingly organic, warm and inviting, but simultaneously modern and new. These lights illuminated the meal at the pottery dinner, and they seem to hold a promise of things to come for Alex, Connie and East Fork.

“Making What I Want to Make”

Alex found his place in a North Carolina lineage of potters only because he had the courage to move away from his own lineage — his own, as Alex puts it quite correctly, “family of artists.”

To be specific, Alex’s mother is sculptor and poet Linda Hoffman, and his father is sculptor and inventor Paul Matisse.

Alex’s sister, Sophie, is a painter in New York City, and his brother, Michael, is a photographer in Seattle.

His grandfather, the art dealer Pierre Matisse, was, for all intents and purposes, singlehandedly responsible for bringing the Modern Art movement to America. After Pierre had an affair with artist Roberto Matta’s wife Patricia, whom he later married, Alex’s grandmother Alexina left Pierre and went on to marry Marcel Duchamp.

Being Marcel Duchamp’s step-grandson is a big deal, of course. But the heaviest weight on Alex’s shoulders comes from the fact that his great-grandfather was one of the most significant artists of all time, the celebrated painter Henri Matisse, who died 30 years before Alex was born and whose paintings, when they come up for auction, fetch tens of millions of dollars.

Henri cast a long and colorful shadow over Alex’s life. So, yeah: When Alex Matisse says he was born into a family of artists, it’s a bit of an understatement. He was raised in one of the most celebrated families in the entire history of fine art.

Discovering how to be seen — and how to see himself — outside of that formidable legacy is the central struggle of Alex’s creative life.

“I think that good art comes from people who have something inside themselves that drives them forward. I don’t think that the outside stuff matters,” he says. “I think that there needs to be some kind of internal drive that comes from somewhere to keep creating better and better work. I see it in a lot of artists. In my own family, there’s a feeling that whatever you are doing, you could be doing it better and there’s a deep sense of never being satisfied with the work that you are doing. That was certainly the case with Henri and he never stopped. He never settled into one thing, he always kept changing and moving forward and something drove him to do that.

“Certainly I feel that there’s a competitiveness that drives me and a feeling that I need to do something big and on a larger scale,” he adds. “But it’s hard to compete with…” — and he pauses for a moment — “my family. My grandfather was an art dealer in New York and he brought over people like Miro and Chagall and Giacometti and represented them in the United States and brought all of that modern stuff over here, kind of for the first time. And he had his own struggles, too. He always felt like he didn’t want to be in the shadow of his father, he didn’t want to feel like he was the direct conduit to his father. My struggle is sorting through all that stuff and just making what I want to make.”

A Brotherhood of Potters

Alex Matisse makes what he wants to make, and he does it prolifically. In fact, one of the things most immediately remarkable about Alex is his discipline: Not yet 30 years old, he has already spent a third of his life singularly focused on the mastery of one art form: pottery.

His great-grandfather Henri once said, “Do I believe in God? Yes, when I am working.” Alex is similarly inspired by and driven to work. And it’s clear that he derives great satisfaction from his work. But it’s also clear that he knows his work could not exist without the community that nurtured it. Here in North Carolina, Alex’s fellow apprentices, their teachers and their shared predecessors became the brotherhood of potters where Alex found his creative home and a new sense of belonging.

In fact, by working as an apprentice to Matt Jones and Mark Hewitt, Alex not only became part of a brotherhood, but an heir and successor to an almost comically biblical litany of ceramic begats. Bernard Leach, known as the father of British studio pottery, was born in Hong Kong in 1887 and raised in Japan. Starting in the 1920s (roughly around the time that Henri Matisse began painting his Orientalist odalisques), Leach and his Japanese contemporary, Shoji Hamada, created what is known as the Anglo-Oriental school of pottery, which reveres the traditional folk pottery of both the East and West and elevates the beauty of everyday, functional pottery crafted by pre-industrial methods.

Leach was largely responsible for exposing the Western world to traditional Japanese folk pottery in a movement known as Mingei, which grew in response to how the Industrial Revolution had devalued handmade objects. Leach’s own work mirrored his similar feelings about the Industrial Revolution. Michael Cardew, who was trained by Leach and whom Alex Matisse refers to as his “ceramic grandfather,” was celebrated for his slipware technique and for his populist politics. Cardew spent 20 years as a potter, teacher and writer in West Africa, and the influence of African pottery is visible in his work and that of his apprentices. It was Cardew who eventually trained Mark Hewitt, who is turn taught Alex Matisse. Hewitt had seen North Carolina pottery traditions that mirrored those of the English slipware tradition, and his own work essentially married the two. Matt Jones, Alex’s other teacher, is a North Carolina native who works in a more traditional North Carolina vein. Jones trained under Todd Piker, another student of Cardew’s.

While the forms and styles of these potters span a century and four continents, at the root of their work was a shared sense of meaning — what potter Oliver Watson described as the “ethical pot,” which, “lovingly made in the correct way and with the correct attitude, would contain a spiritual and moral dimension." When this lineage of pottery made its way to the American South, it cross-pollinated with the living tradition of the North Carolina Quaker and Moravian slipware potters, as well as the hundreds of years of African-American pottery traditions that developed under slavery and continue to grow and evolve every day.

The South, for better and for worse, is slow to change. Many of our craft and social traditions have resisted industrialization and remained intact, especially in the farther reaches of Appalachia and the rural Piedmont, because of poverty, a lack of technology and their geographical distance from industrial centers. But, in some ways, our survival as people (as well as that of our cultural traditions) has depended on our ability to adapt to change from the outside world — including some complicated twists of fate, such as the one that saved the North Carolina town of Seagrove’s pottery industry from extinction. During prohibition, the thriving “jugtowns” of Moore County, N.C., lost their primary source of income making jugs for the whiskey industry. But it was at that time that the late Jacques and Juliana Busbee, artists and collectors from Raleigh, began to collect and promote Moore County pottery as functional art — eventually opening a tearoom in New York’s Greenwich Village to sell the work. The Busbees built their own Seagrove pottery, called Jugtown, which, in addition to creating the traditional shapes and glazes of North Carolina, also created “translations” of Chinese ceramics. So Seagrove pottery survived — by an uncanny relationship between tradition and modernity — and evolved and continued to be influenced by British, African and Asian pottery, as well as the tastes of consumers outside of the South. And so it was here in North Carolina that Matt Jones, Mark Hewitt, Alex Matisse and their brotherhood could flourish, because the knowledge was here, the infrastructure was here, and here was a culture of people who appreciated pottery and who had never stopped appreciating it.

The brotherhood is growing. Just last month, a new potter joined the fold at East Fork: John Vigeland, former apprentice of Daniel Johnston (another student of Mark Hewitt’s), came to make a permanent home at the pottery. John and Alex, by virtue of having been trained in the same lineage, have a “common language” of pottery, making it easy and intuitive to work together and to support one another. Their work shares a common East Fork mark, with individual pieces differentiated only by a small “J” for John’s work and a small “AM” monogram for Alex’s.

“We’re part of the same family of pottery,” John says, “from the way we set up the workshop, to how we keep it clean, to our work ethic. We reflect each other and the way we see pottery and think about it is very similar, so we have a mutual understanding.”

Pottery seems, as a discipline, to be naturally familial, the making and firing of the pots naturally social, the uses of them naturally domestic. So it makes sense that there is a communal feel at East Fork — one that is branching out to encompass other potters in Madison County. The guild-like sense of mutual support among the county’s potters is a source of fervent pride.

Last Names Be Damned

When I first set out to write about Alex and Connie, I decided, sight unseen, what I wanted to discuss. I wanted to ask, from my own perspective as a native Southerner: Why should we care about the life of a man from Massachusetts and a woman from California who had adopted the traditional crafts of Western North Carolina? These crafts were originally simply modes of survival for the poor. But I wondered, were they now becoming the “artisanal” pursuits of the sons and daughters of the privileged class?

I felt really clever about this angle. I was born and raised in the suburbs of Atlanta, with deep roots in the Georgia towns of Cordele, Monroe and Cartersville. I’m as proud of my kinfolks’ strength and survival as I am ashamed of the legacy of hate for which the South is more often known. Part of my life’s work is celebrating, through food and writing, the richly diverse cultures of Southern people, black and white, rich and poor.

I’m protective of those cultures, so in writing this piece I thought it would be really interesting to look at Alex’s work critically — as a co-optation of a traditional Southern craft by a rich kid from the North. And it’s a legitimate question: Leach and Cardew both came from privilege, so could they have done the work they did without the patronage of inheritance? Are the British and Northern potters who come here for the clay colonizing North Carolina pottery or preserving it? Would Henri Matisse have had the time to to change the way the world sees color had his father not been a rich grain merchant?

So I went to East Fork asking all these tough questions. But the more I tried to get answers, the more they eluded me. After two weeks I began to feel like I was slamming a pickup truck into a solid cinderblock wall, putting that bitch in reverse, backing it up and doing it all over again. Finally I had to come to terms with the fact that my approach had been wrong all along. I couldn’t write the story I had set out to write, because that story wasn’t true.

I came to see more and more clearly that while Alex’s work bears his own distinctive voice, his lexicon is pure North Carolina, as much as his clay, his glazes and his wood ash reflect the Carolina landscape.

Alex Matisse is not an outsider. The only thing he’s ever been, since the day he took that first apprenticeship, is a North Carolina potter, one who became what he is today through his own effort. His famous last name didn’t have a damned thing to do with it.

Still, Alex understands why people ask the questions. “It is the great thing that consumes me to the point of destruction,” he says. “I’m much more aware and sensitive to other people’s perceptions of me having to do with privilege. It is part of my narrative. I think about it all the time.

“You have two options. One is to not tell anybody, to hide from what you are trying to do, what you’re not comfortable with. The other is to be open about it, and that’s hard. It’s not the attractive narrative. I’m trying to reach a point in my life where I’m upfront and honest that [my family background] is just part of who I am.”

Matisse feels a deep artistic connection with Daniel Johnston, Vigeland's teacher and a potter who grew up in far more humble circumstances in central North Carolina. But sometimes, Alex finds himself comparing his own artistic struggles with the more real-world struggles that faced Johnston as he built his career.

“He is the genuine article, a fantastic, amazing potter, and if there is a story of someone doing it on their own, it’s his story,” Alex says. “Not that mine is devoid of struggle, but if it is devoid of that kind of struggle, how does it have merit? The only thing I can I say is: Good art transcends everything. Good work transcends all of that, and if you are going to make good work, then the good work stands on its own. And I’m not saying I make good work. I’m just saying that I’m striving to do that. If you are a creative person, you create regardless of your condition, and the work is first and foremost.”

Over the five weeks I spent visiting East Fork Pottery, I came to agree. The phrase “all wealth is from the earth” has been ringing in my mind all this time. The joy of making something from only the most basic elements — earth, air, fire and water — with your hands, making it truly, transcendentally beautiful: Nobody owns that, and nobody can take it away. Nobody has a corner on authenticity, whether you’re from the South or not, whether you’ve had economic struggle or not, no matter who your daddy or your granddaddy or your great-granddaddy is.

In searching for the South, we often end up defining ourselves by what we are not, rather than celebrating who we really are and where we came from. If we’re going to be truthful (and we should be) about celebrating ourselves, then we better get real and recognize that everybody is somebody and everybody is from somewhere. We all just happen to have landed here in this particular, peculiar corner of the earth: by birth, by choice or by happenstance. No matter why we’re here, here is where we are, and here is where we create.

In our work, we meet our ancestors — whether our blood ancestors or our spiritual ones — and we are connected to them in one long, loving arc of beauty. They give us stories that feed us and teach us how to live. And whether you’re from Massachusetts or Mississippi and whether your history is rooted in the salt of the earth or the noblesse oblige, your work can be your redemption. You can use your work to forge a meaningful life, to reach out over the past and into the future to make something timeless, something beautiful, and your work will stand on its own merit as a result of your struggle.

Alex Matisse came to the South to do his work because this is where he could do it best. And that’s a Southern story if I’ve ever heard one.

Apples in Our Knapsack

My 8-year-old son, Jasper, and I drove out to East Fork Pottery recently for an afternoon. My son and I hung out, chatting in the workshop with Alex and John. We helped to mix glazes in giant barrels, glazes made from North Carolina clay and ashes from a nearby wood-fired bread bakery. We watched John and Alex raise pots from spinning wheels. I had a sense that I could stay there forever, it was so pleasant, watching the kinky-tailed tomcat sun himself, watching the pots dry.

We went for a walk in the woods. We walked past the 1920s farmhouse, past the old Airstream trailer, past the wild ginseng patches. We climbed a path, ever higher, along a stream lined with what mountain people call a “laurel hell” — a patch of mountain laurel so thick and deep that once inside, you could lose your sense of direction and not be able to find your way out. We crunched quartz under our boots, with Alex’s sweet old dog, Zuma, trotting alongside us. As we climbed, we caught up with the setting sun, and as we got almost to the top of the ridge, we found a gate, behind which a wide, curving pasture was cupped in the slope of the ridge. And then there was a farmstead, meticulously kept. A barn, a farmhouse, a springhouse, a rusted-out pickup truck and a child’s playground — the grass mowed, the hostas and roses immaculate, the apple trees dropping fruit. It was a place out of time, illogically and uncannily preserved by a neighbor — though the farm itself had been abandoned years ago.

The storytellers up in this holler say the house was long ago inhabited by an African-American family. Their names are lost to history. But all by themselves they carved a life out of the side of this mountain. Perhaps they made pottery or goat cheese. Certainly they baked bread and raised crops. They likely struggled, suffered and labored, and surely they found joy, made love and reveled in beauty. And then they died, the whole family cut down by yellow fever at the turn of the 20th century, and were buried in graves marked only by rocks on the ridgeline.

We, the living, stayed there on that mountainside for a while, Jasper playing on the swing set and John, Alex and I quietly picking apples in the full glow and glory of the setting sun. We munched the ripe, wild apples happily, then tossed the cores to the dog. Then the sun went down and we came down off the hillside, back to the house, back to our cars, back to our jobs, back to daily life.

As we came down the mountain, we carried the past with us, like so many apples in a knapsack, to feed us on our journey.

L.A. Woman

What happens when a young woman with deep roots in Los Angeles finds herself living deep in an Appalachian holler in Western North Carolina, a place known for a brutal Civil War massacre? How does she adapt? Connie Coady ultimately decided the answer was about being loyal to her own Angeleno traditions.

Main Story by Jodi Rhoden

Sidebar by Chuck Reece

Photography & Video by Whitney Ott & Jaemin Riley

Next Week:

We Get Fictional

For the first time, The Bitter Southerner brings you a new piece of fiction — specifically, a short story by Atlanta writer Thomas Mullen, author of “The Many Deaths of the Firefly Brothers,” “The Revisionists” and “The Last Town on Earth,” which The New York Times Book Review praised as “remarkable ... brilliant ... nerve-shredding.” We could say the same about “Last Call at the Stork Hotel,” the story we'll bring you next week, set in a hotel in China where Americans spend their last nights awaiting their chance to adopt daughters.