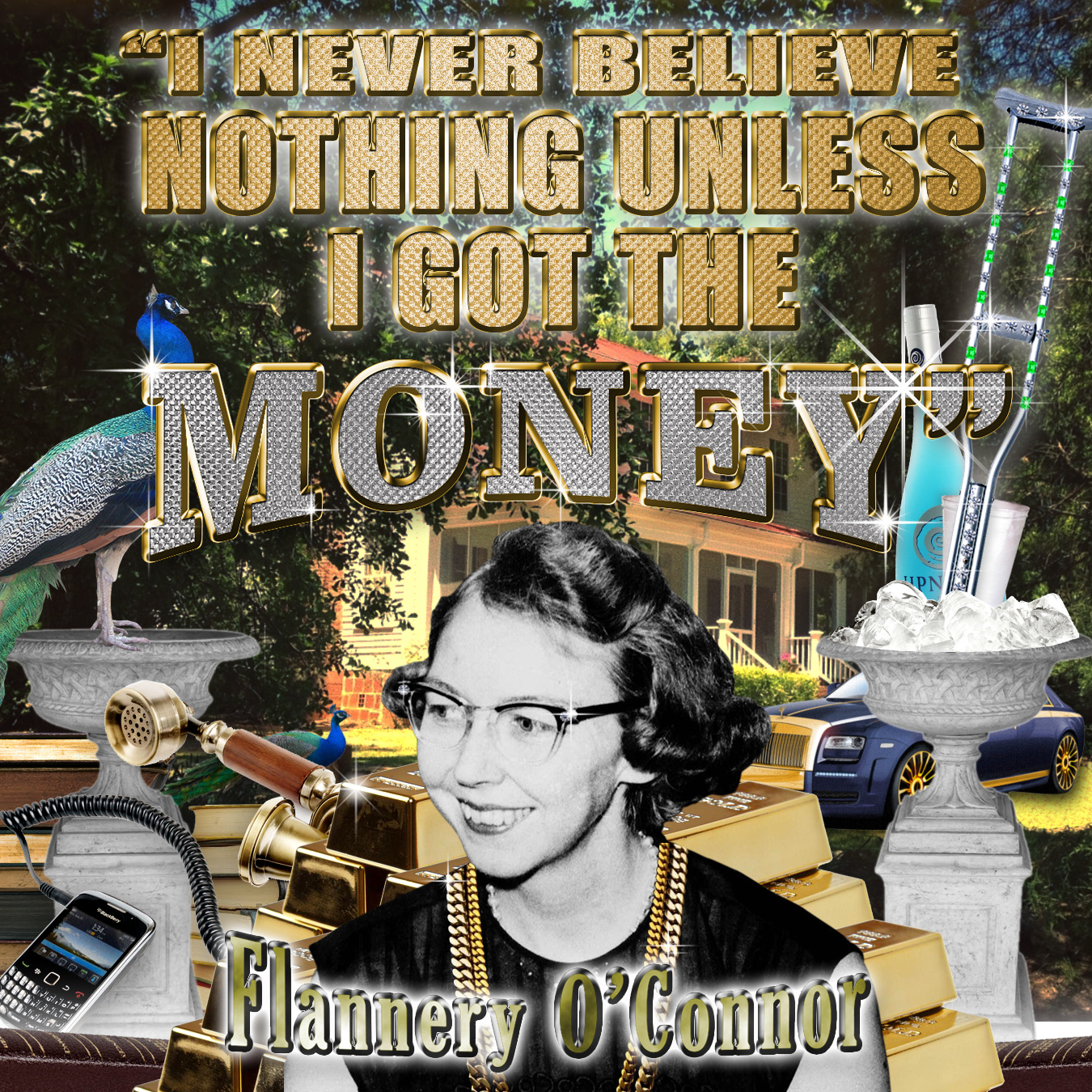

Scale Highly Eccentric

A Written and Illustrated Tribute to the Talent and Toughness of Flannery O’Connor

When Atlanta designer and illustrator Brooke Hatfield first dreamed up the idea of publishing a tiny magazine featuring 14 artists’ interpretations of Flannery O’Connor, it’s reasonable to expect that a few saw her idea as eccentric.

But hell, we like eccentricity down here. And being odd never held back Ms. O’Connor herself. Moreover, Hatfield had her dad’s words ringing in her ear: “God never blesses a man leaning on a shovel and praying for a hole.”

So she dug. It didn’t take Hatfield long to find a group of writers and designers who could match her eccentricity for eccentricity. Her own portrait of Ms. O’Connor is rendered in a most unusual medium: custard. Flannery in flan, one might call it.

The result is “Scale Highly Eccentric.” The publication was launched in June at an event in Atlanta, where Hatfield unveiled the 14 portraits of Flannery. Five writers — ranging from a 15-year-old high schooler to a retired journalist — embodied in their own distinctive ways the legacy of Flannery O'Connor, perhaps the most determined and clear-eyed Southerner ever to pick up a pen.

The Bitter Southerner is proud to present all 14 portraits, plus audio recordings and text from the five writers. But first, a few words from Hatfield herself — words of the sort that can warm the bitter heart.

Brooke Hatfield Photo by Jason Travis

In 2012 GOOD Magazine laid off most of its editorial staff, a really smart team that worked well together. So they Kickstarted a one-shot magazine called Tomorrow, which I helped copy-edit, and it was really inspiring to see how possible it was for that kind of collaborative creative project to work. Google Drive alone makes things so easy.

I was really drawn to this idea of convening a bunch of talented people into a specific project. And once I got the idea for this zine about Flannery O'Connor, I couldn’t stop thinking about how possible it was. And I knew that I had insanely talented friends who would really shine on a project like this. Who was I not to connect those dots?

I grew up in rural southwest Georgia, and for most of my childhood I felt like a weird, loud kid who did not fit in. I equated success with leaving the South for some fabulous huge city, which I did for a couple years, in Washington. And I really missed Atlanta. I feel like I’ve seen the South from both sides now.

O’Connor thought she had to leave, too. She writes: “I stayed away from the time I was 20 until I was 25 with the notion that the life of my writing depended on my staying away. I would certainly have persisted in that delusion had I not got very ill and had to come home. The best of my writing has been done here.”

Howard Finster churned out masterpiece after masterpiece in Summerville, Ga. I do not stress about not living in New York City. I can produce the work I want to make right here. If anything, the cheaper cost of living in Atlanta makes that easier.

A part of me gets really sad when a creative, progressive friend moves to Los Angeles or Chicago or some larger media market, because those cities don’t need them like the South needs them. They can do amazing things right here.

We’re still only a couple generations removed from segregation and Jim Crow. There is a lot of healing yet to do, and that reconciliation is some of the most important work my generation is undertaking.

by Carleigh Knight

My father and I have the same marble green eyes and slight gap between our teeth. I liked watching him when I was little cause I knew that'd be me one day. Sure, I'd never weigh 280 pounds, shave a thick mustache or wear tube socks with a tuxedo like my dad, but I knew one day I'd sip a little Crown when I was sick, brag about my high school 400-meter time, and drive across the Carolinas eating boiled peanuts, drinking a Budweiser out of a styrofoam cup and listening to "Guitars, Cadillacs..." on tape. He locked us out of the house until we could throw a decent spiral, taught us how to play blackjack for 50 cents a hand, and insisted we learn every word to "Gimme Three Steps." He didn't raise my siblings and me as boys or girls; he raised us as Southerners. Independent. Proud. Happy.

So I was determined to be what I saw in my dad: someone with a real sense of himself, a joy in his accomplishments, a humble acknowledgment of his shortcomings. And I was doing a pretty damn good job under his tutelage running around the hills of western North Carolina, until I reached the world's roughest waters, the place that tests even the strongest of ships, the vessel that houses life's most excruciating lessons: middle school — specifically, Coach Ledford, my seventh grade gym teacher. He stood at 5'4" with spiked, blond hair on his head and a mustache that was disturbingly trimmed. While he was the golf and basketball coach, the biggest title he held read, “Leader of FCA,” the esteemed Fellowship of Christian Athletes. Needless to say, he hated me. I worshipped Tori Amos and quoted her in class and sang Jim Morrison lyrics during the timed mile. My sister and I wrote formal complaints about his obsession with prayer: before school, before basketball games, right in the middle of health class. He was the righteous, right-wing, tucked-in athlete and I was an opinionated drama geek who never passed the Presidential Fitness Test.

So one day, he takes my class outside despite the drizzling rain. This, of course, was the exact type of damp weather that made my long curly hair look like someone teased Reba McEntire's 1988 perm with a Brillo pad.

I always knew I had different hair, from my family, my friends, the perfectly preened celebrities. It felt like a cornhusk broom and tended to grow up rather than down my back. But I liked my big, textured hair just fine; it made me stand out among the other kids, and in the ’80s and ’90s, standing out was totally the rage. I did, however, have something I was not so proud of. Underneath my 10-pound bed of curls lay a tangled knot about the size of a baseball I nicknamed, “The Rat's Nest.” It was beyond combable, like a sphere of tattered felt that that draped behind my neck. So, I did what most 13-year-olds do with a problem. I ignored it.

So anyway, Coach Ledford lined us up in the middle of the field. “Hey, uh, what's wrong with that hair of yours. Is it fuzzy or frizzy?” he said walking over to me. “Do you know it looks like that? I mean, I just can't figure it out. Is that called fuzz or frizz? Haha, maybe it's something new called fuzzy frizz!” He toppled into unbearable laughter. The wind picked up and I started to cry, hoping the raindrops hid the tears from my classmates. When he recovered from his hysterics, he sent us all back inside.

So there it was. Reality came pouring down like a deluge of truth: my hair, myself, was nothing more than fuzzy frizz, you know, the type of stuff rats use to make nests with.

When I got home, my dad high-fived me immediately. He said mom finally acquised to our KFC demands. I sighed and said fine. Even though I'd been begging for KFC for months, nothing mattered anymore. I was ugly. And weird. And embarrassed. I didn't speak a word on the way there and my dad kept talking about mashed potatoes, until my silence lead him to ask me what was wrong. What could I tell him? That he produced a freak of a daughter? That I was enraged my family never told me how hideous my hair was? That stupid Coach Ledford finally won? Against me?! Someone who could throw an amazing spiral and spit watermelon seeds a good six feet across the yard and outrun any boy in the 50-yard dash and who was brazen enough to join her high school sister in writing letters to the principal explaining the atrocities of blending church and state? In what universe could a weaselly old redneck beat a strong Southern girl like me? And worst of all, I simply couldn't tell my dad, the man I was going to be one day, that I had allowed this dumbass to make me cry.

My dad called anybody who upset him a “sonofabitch,” made a few jokes and then swore that asshole off for good. I cried. And didn't speak up for myself! I didn't even utter a smart-aleck remark under my breath. Who was I? He said he wouldn't go get our fried chicken until I talked, turned off the car and sat there. Sobbing, I told him. He cleared his throat, said that Ledford wasn't any type of man or teacher, and that I had beautiful hair. Then he got out of the car, and I took a deep breath. Dad knew. It was over. It was kinda funny, in way, when I retold it. Sitting alone in the parking lot drying my face in the red neon glow, I decided I'd be ok. When dad got back, he handed me a drumstick. We ate it in the car, listened to the radio and went home.

To my surprise, Coach Ledford pulled me out of band and apologized the next day. His ice blue eyes never met mine, they just nervously bounced from the floor to the ceiling. As he leaned against the lockers, I towered over him, and realized that he spiked his hair because he was balding. He spoke so quietly that I had to lean in a little, and I noticed that he wore the mustache because his nose was bigger than a roman candle. I accepted his apology and walked away feeling a little sorry for him. See, weasly old rednecks get their strength from making others feel small, and strong Southern girls get their strength from finding what's big inside of themselves.

By the eighth grade, I finally exposed the rat's nest to my mom and sister, who encouraged me to cut a cute bob and rid myself of the creature that lived underneath my hair. By ninth grade, I was just another normal freshman girl, class treasurer. Rising track star. But one thing was weird: I could get away with anything in gym class. I was constantly late, drank juice in the weight room, refused to do anything basketball-related, and still, an A on every report card and no detention. I mentioned it once to my older sister who replied, “Obviously! Our dad threatened to beat up Coach Ledford. Every damn gym teacher in Buncombe County is afraid of you!” What? Why? I looked at my sister perplexed. And then she told me that thing dad told her to never, ever tell me.

The next morning after our KCF confessional, he burst into the principal's office unannounced, demanded to see Coach Ledford, and after a few threats of causing a massive scene, the principal called old Ledford into her office. Dad, a submarine of restrained anger, glared at Ledford, raised his voice and declared, “I've spent my life raising my children to look up to teachers for leadership and guidance, and you half-witted, small-minded redneck son of a bitch don't deserve the title. You think it's OK to talk to my daughter like that? If you ever say anything to her again, well, let me tell you one thing, right now. I'd never kick your ass on school grounds, as I have too much respect for educational institutions. Oh, but Ledford, you don't live here, so I will find you, and take pleasure in kicking your ass.” Then he thanked the principal for her time and walked out without waiting for a response.

I recently asked my Dad why he never told me about his assault on Ledford. “Life is hard as hell, my middle child, and you gotta deal with that shit on your own,” he said. Then he paused, raised a finger, sipped his beer and started again, “The sharp edge of a razor is difficult to pass over, thus the wise say the path to salvation is hard.” On that day in middle school, I guess he gave me what every strong Southerner needs when crossing over the razor's edge: time alone to think, someone to get your back, and a good piece of fried chicken.

Carleigh Knight came of age in Asheville, N.C., and now lives in Atlanta. She teaches high school English at the Fugees Academy in Clarkston, Ga.

by Kay Powell

“It’s for every woman.”

Here we sit in our nice new offices at our nice new desks with our nice new diplomas framed and hung to begin our mandatory “brag wall.” We’re wearing our nice new work, not casual, college clothes complete with pastel bow ties because we’ve read “Dress for Success.” We’re ready to put our nice new degrees to work to change the world right after we have coffee from our cups that proclaim “As you climb the ladder of success, don’t let the boys look up your dress,” all for 59 cents for every dollar our male co-workers earn.

We are women of the ‘60s.

Meanwhile, Lorena Weeks makes the 40-mile round trip from her home in tiny little Wadley in rural east Georgia to Swainsboro to work her night shift as an operator at the Southern Bell Telephone Company. Lorena graduated from high school in 1947 on a Friday night. On Monday she interviewed with Southern Bell and by 10 a.m. was on the job as a telephone operator. She wanted to be a nurse. All that changed after her mama and daddy died. She was 18 and the sole support of her younger sister and brother.

Early in Lorena’s career, they lived in a one room apartment in Louisville, 10 miles from Wadley. In the afternoon, Lorena worked at a restaurant for tips and a free vegetable meal for her brother. At 8:30 p.m., while the children slept, she caught a bus to work at the telephone office in Wadley from 11 p.m. until 7 a.m. She returned to Louisville with the mail carrier. She knows if the chance comes for a better paying job, she is going for it. That chance comes when President Lyndon Johnson signs the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

In 1965, Lorena applies for a switchman’s job opening. It is an easy indoor job she is entitled to by law and by seniority. Southern Bell ignores the law and her seniority and denies her the higher-paying job. The company tells her outright that the job is given only to men. It cites Georgia Rule 59 that women and minors cannot hold jobs requiring them to lift more than 30 pounds. The relay time and test set used in the switchman’s job weighs 30¾ pounds. A woman carries around a baby weighing more than that.

Lorena files a grievance with her union. It is denied. The union president tells her, “If you get this job, there will be women all over.”

“That’s what it’s all about,” Lorena tells him. “It’s not just for me. It’s for every woman.”

Every paternalistic rationalization is thrown at her: Men are the family breadwinners; the rule protects women from harm. Lorena knows none of that is true. She contacts the EEOC. It supports her. Southern Bell still denies her the job.

“I was going to have that job one way or another,” Lorena said. “I don’t care if I have to go all the way to Chief Justice Earl Warren. Somebody will listen to me.”

In 1966, she sues Southern Bell. The company misrepresents in court how the switchman’s job works. Lorena loses the case. Her lawyer quits. She is left high and dry and upset. Shortly, her case comes to the attention of the nascent National Organization for Women. NOW takes it on.

The Wadley telephone office closes. Through three years of legal appeals, Lorena commutes to the Swainsboro phone office.

She becomes a hermit in her hometown as friends fall by the wayside. “I couldn’t sleep. I stopped going to church because the preachers were preaching about these bad women,” she said. Her life is lonesome. She must give up teaching Sunday school for the handicapped and being a Girl Scout leader. She does not take the litigation and harassment home with her. She talks about it only with her lawyer.

Worn out and torn down, she copes daily with abuse from her bosses. One suspends her for handwriting rather than typing her daily reports. She tells him the typewriter she has to move to her desktop daily weighs 34 pounds and she’s not about to break Georgia Rule 59. She files a grievance with her union and wins.

After years of appeals, on March 4, 1969, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals rules in Lorena’s favor.

The court says in part, “. . . Title VII [of the Civil Rights Act] rejects just this type of romantic paternalism as unduly Victorian and instead vests individual women with the power to decide whether or not to take on unromantic tasks. Men have always had the right to determine whether the incremental increase in remuneration for strenuous, dangerous, obnoxious, boring or unromantic tasks is worth the candle. The promise of Title VII is that women are now to be on equal footing.”

Lorena Weeks’ case establishes the law for equal treatment of women in the workplace. Appeals continue because Southern Bell still does not give Lorena the switchman’s job.

Federal Appeals Court Judge Griffin Bell is astounded. In 1971 he issues a court order demanding that Lorena be on the job the next morning. Southern Bell finally gives her the switchman’s job along with continued harassment.

A co-worker gives her the wrong equipment to do the job. Bosses lock her out of the telephone building then accuse her of being late to work. The company tries — against the court order — to transfer her. Her old boss asks her new boss, “Now that you have her, what are you going to do with her?”

“Work her ass off,” her new boss says.

Her bosses at Southern Bell never stop trying to get rid of Lorena.

We women of the ‘60s retire from jobs that now pay us 77 cents for every dollar a man earns. Few of us know the hell Lorena Weeks endured and conquered. Few of us know of her determination and sacrifice to make the workplace fair for us.

Lorena Weeks is retired, too, living in Wadley. She applied for the Social Security benefits she earned after 36 years with the phone company. The Social Security employee figured Lorena’s benefits and exclaimed, “This is the highest Social Security I’ve ever seen for a woman.”

“Well,” Lorena said. “I got a man’s job.”

Kay Powell retired as news obituaries editor of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

We were related to Sam Houston—governor of Tennessee, governor of Texas, rememberer of the Alamo—but not to Whitney. I learned this about my family ten years or so after being born into it. I was not quite sure how this could be true but I did not press the issue. Of more personal interest to me at the time was the fact that we also had a castle. After my father’s father died, my grandmother went with her sister Lucy and their cousin Billy to Scotland and found it, walked around and through the crumbled gray keep and the jagged tower on the cliff overlooking Loch Ness. Billy took a photograph my grandmother later framed and hung on her dining room wall, under the tartan swatches and the coats-of-arms of the rest of the family’s families: the Comyns, the Carrs, the Jareds, the Lowes. Someone among them had fought alongside William Wallace, or so we were told, or so we told ourselves. When I watched Braveheart, years later, I found myself trying to pick out familiar faces among the face-painted hordes. There were a few.

—

This piece was recently published in Guernica, and you may read the full text there. Maddux reads the full piece in the recording above.

Rachael Maddux is a writer and editor living in Decatur, Ga. Find her online at rachaelmaddux.com and @rachaelmaddux.

by Jolisa Brown

It’s Saturday, which means it’s party day. It isn’t just a regular party day though; it’s the party day. All year I have waited for the open party that would grant me access to Oliver Conuken in a social setting. I have been very patient. I couldn’t just show up to one that I wasn’t invited to. That would put suspicion on me, thereby ruining my plans. The plan I’d created counted on him having his guard down, being drunk, being vulnerable. It counted on him being surrounded by a crowd of people and incapable of shrugging off the question, calling me a loser, as he’d before done in private. It counted on all his dirty laundry being out in the open so that he had to confront it, either to deny it or confirm it. My plan was dependent on the suspicious bodies of his peers forming a slight barrier, being a little less than eager to move as he tried to run away. It counted on them sending the message, “For this we need answers. Over this we cannot drop our heads and blindly follow.” And today, the stars have aligned so that just this can happen.

Although I was ready for the party, before I had not been certain that it would ever take place. I before could only hope that the circumstances might soon line up so that what indisputably needed to happen could happen. My outfit for this party was a part of my disguise. I had managed while working among and alongside these people for years to elude their attention. None of them knew me. The objective, as mentioned before, was to stay unnoticed. So, my outfit was one that served its purpose. It was not exceedingly attractive but also not exceedingly dull. In dressing in this way, I ensured that people would not see my vaguely familiar face and have a curiosity that would make them grasp for who I am. Because then, perhaps, they would remember, and my plan would fall apart in tatters.

I was dressed in a mullet skirt with Vans. Jade earrings dangled from my ears, and three jangling bracelets hung from my wrist. My sea-green t-shirt was just tight enough to show that my body wasn’t completely a flop but also just loose enough to deflect any interest from boys who wouldn’t quite be able to place what my figure was. The skirt was also a respectable length, right dead-smack between what would qualify as skanky and what would qualify as modest. I was very, very normal. However, I would be the most different of everyone at the party. I had a motive.

Fifteen minutes later the horn of a taxicab sounded to alert me to its arrival. I wasn’t chancing public transportation for an event so critical. It was 12 a.m. The party had started at 10 and would undoubtedly be in full swing by the time I arrived. The key to hiding in plain sight was to have a lot in the environment to distract from you. Once I arrived, the chaos would work to my advantage. The drunken, disoriented sheep would be my cover, and in their shade I could do as I pleased.

My small, black purse that I carried with me everywhere sat on one of the hooks of the coat hanger by my door. Why I owned a coat hanger, I wasn’t not sure. I had exactly one coat and never invited guests over in my private space, yet at some point I had picked it up, maybe before the incident that changed it all, back when it was actually conceivable that I’d invite people into my home. As I exited, I grabbed the strap of my small purse and slung it over my shoulder, feeling it settle comfortably in its space right below my right hip. It bumped against my side as I reached to flick the light switch for the front room, located just beside the obsolete coat hanger. I reached for the doorknob in the mild darkness, turning it and bringing the door open. I exited, turned around, and locked the door with the lock I always keep in the front pocket of my small rectangular purse. I returned the key to its rightful place, walked awhile, turned left, and found myself at the front door of the apartment complex.

The taxicab that I found waiting for me was a bright yellow. On its side was a checkered stripe that curved around the entire car, and above the stripe the words “Cumberland Taxi Co.” were printed. I strode towards it, my nerves steeled and my plan for the night running through my mind. I slid into the vehicle and told the man my destination: 872 Woodworth Road.

He gave me an overworked smile; lines reached into the fat of his cheeks resembling parentheses. Then, he pulled off. We exited the apartment’s small parking lot and started onto the worn, gray roads of Cumberland. The ride would be maybe 25 or 30 minutes. I looked out the window and saw the mountains I was so familiar with. They were what separated us here from the rest of the 5 million inhabitants of the state. In seclusion, lunacy was allowed to ferment and grow in this town. The crazies overpowered everyone else, and the “everyone else” was okay with that, so long as they got to keep their non-confrontational lifestyle.

Today would be the end of that.

As I’d predicted, the party was well along when I arrived. Music boomed from a single house set a ways back from the street. Every window in the house was alight. There were tiki torches set around the perimeter of the yard, where the odds of someone drunkenly stumbling into them were lessened. The faces of the party-goers were illuminated in the flickering lambency of the mystic torches.

The cab didn’t pull into the driveway, where a couple other cars were parked, or even on the side of the road, where parked cars had already claimed all the available spaces and stretched into infinity.

Instead he just stopped in the road, no cars behind him, and asked, “This it?”

I responded, “Yep.”

I paid the taxi man 15 bucks. Then the bright taxi pulled off, leaving me to my work. I stepped out of the street and onto the lawn. There were maybe four or five trees on the property and a large ring of hay surrounded each tree’s base. There was a garden that extended from both sides of the house's six front steps, and a stone path extended from the driveway to the steps. The party had what I estimated to be between 300 and 350 people, which was perfect. That meant that almost the entirety of the sophomore class had attended as I’d hoped.

All these poor unfortunates drunkenly stumbling around attended the Allegany College of Maryland, and all of these kids had known each other for more than likely all their lives. They’d all at some point stolen each other’s boyfriend/girlfriend, cut each other off at some stop light in the middle of nowhere, or been dragged into a conversation about their hopes and dreams and future by one another’s parents.

The front door of the house slammed open, and I saw, standing there, none other than Oliver Conuken, the very reason why I was here this night. A plastic cup was in his hand, and he was laughing raucously, apparently at something funny someone inside the house had said. He looked out onto the vastness of the party he’d thrown. Then, he looked over the metal rail of the steps and vomited into the beautiful garden. Oh, yes. He was thoroughly wasted. And the time had come, for revenge.

Jolisa Brown, 15, currently resides in the city of Atlanta where she spends her free time reading, people watching, and running through the most bizarre shows she can get her hands on. She is a student at the Westminster Schools of Atlanta and hopes to one day get a dual major in social psychology and creative writing.

Shannon Keebler hovered over the workbench in her garage running her finger across the blade of the chainsaw she fashioned from an orange juice jug, three-inch PVC coupler, wooden board, bike chain, and miscellaneous hardware. Before her interview for Zombie Bride #2 began five months ago, before she offered a firm but non-feminazi handshake to Randy Folan, the hiring manager at Poltergeist Plantation, she knew she had nailed it. While most recent college graduates who couldn’t find office jobs showed up to the Poltergeist Plantation corporate trailer donning pencil skirts and Sunday Best suits, Shannon wore a white lace dress slathered with red acrylic paint, her hair meticulously disheveled with Kevin Murphy Texture Master spray. When Randy Folan greeted her, she pointed the bike chain blade at his face.

Because of Shannon Keebler’s interest in low-budget costume design, customer service experience at Party City during the Halloween onslaughts of 2010 through 2013, and enthusiastic expression of dressing for success, Randy Folan decided to pay her $1.35 more per hour than Zombie Bride #1. Zombie Bride #1 had racked up two years of tenure at Poltergeist Plantation but refused to go shoeless for fear of messing up her feet and ignored Randy’s suggestion that she show some cleavage with maimed artificial nipples.

While the garage door opened, Shannon Keebler stood there reflecting on her stint at Poltergeist Plantation and curled her index finger around her prop’s plastic handle, scooting it to the far end of the workbench. She hoisted her new Ryobi ONE+ cordless chainsaw off the floor instead, slung it in her trunk, and drove to her 5 p.m. shift.

Shannon parked in the Employee of the Month spot in Lot A and left her flip-flops in the floorboard. She slinked through a field of Queen Anne’s Lace toward the Living Dead Chapel, dragging her Ryobi ONE+ cordless chainsaw behind her. Every flower she stepped on in her path leaned, forming a wedding gown train.

Shannon assumed her position at the altar with Zombie Groom #2 and the Phantom Reverend. Randy Folan sort of hid in the back corner gathering fodder for Poltergeist Plantation’s annual performance reviews. When he noticed Shannon’s upgraded faux chainsaw he smiled and gave her a thumbs up, flashing a pair of vampire fangs he picked up at a Halloween pop-up shop in the Marshalls shopping center. He scraggled some notes on his clipboard. Although Randy Folan was skinny, his cheap tuxedo looked one size too small.

“Did you hear that Miss Pierce is bringing her sixth graders tonight?” Zombie Groom #2 asked, picking at the baby’s breath on his boutonniere, which Shannon had fashioned from materials she found in the clearance bin at Hobby Lobby and misted with brown spray paint in order to communicate decay. Shannon was the kind of person who remained silent so long after asked a question that people figured she was either hard of hearing or a snob. Zombie Groom #2 had grown comfortable with Shannon and stopped expecting her to ever answer.

“Miss Pierce creeped me out back in the day,” he continued. “She hugged people too much.”

The lights dimmed and a bell rang, signaling five minutes until showtime. Narrowing her eyes, Shannon thought about Miss Pierce’s 1980-something Honda Accord always parked two streets over from the Keebler homestead in the cul-de-sac on Hummingbird Lane, where her best friend Margaret lived when they were in high school, and how sick she felt when she watched her little brother Kevin slink through the space between two shrubs and hop in the passenger’s seat.

“How was basketball?” she asked Kevin later that night at the dinner table.

“Huh?” he asked.

“You said you were going to play basketball at the Y after school. How was it?” she repeated, slamming down the bowl of marinated cucumbers.

“Fine,” he shrugged.

“Keep it up, sport,” their father mumbled while staring into the living room at the television.

“How’s basketball going?” she asked another evening after studying with Margaret.

“It’s fine,” Kevin answered, grabbing the bread basket. Shannon kept holding the bread basket as well as Kevin’s gaze.

“You should try out for the school team this year since you’re so into it,” she squinted.

“Go for it, champ,” their father added, glancing up from his plate of spaghetti.

Kevin, now 18, would move to Athens, Ga., to attend college in the fall. He still sucked at basketball.

The bell rang again, denoting the 30-second countdown. Zombie Groom #2 flipped on a strobe light, the Phantom Reverend opened his Bible, and Shannon cranked on her Ryobi ONE+ cordless chainsaw. Kids filed down the aisle between the makeshift pews. Shannon had forgotten how young sixth graders look, and that made her snarl.

A girl in a Black Flag t-shirt mass-produced by popular tween retailer Delia’s led her little clique to the altar and crossed her arms.

“Give me a break,” she laughed, deriding Shannon’s Ryobi ONE+ cordless chainsaw. Shannon held it over their heads, and the gaggle of girls ran away.

“‘Til death do you part!” the Phantom Reverend cackled, pulling a plastic knife from the Psalms section of his Bible. The majority of the class cowered and moved like an amoeba toward the exit, onward to the Haunted Cafeteria.

Miss Pierce lagged behind with the stragglers, holding one boy’s hand. Once they reached the altar Shannon held her breath and sliced through Miss Pierce’s forearm. The little boy screamed, dropped Miss Pierce’s hand, and dove over the pews.

“What the fuck?!” Miss Pierce screeched.

Shannon kicked her in the stomach, knocking her down, and cut off her other arm just below the shoulder.

“This is for Kevin,” Shannon seethed. “Keep your hands to yourself. What’s your name?” she yelled at the little boy seeking shelter behind the pews.

Shannon stomped toward him and demanded, “I SAID. What’s your NAME?”

“Danny!” he squealed.

“This is for Danny, too,” Shannon noted. “And whoever the hell else.”

Blood saturated the rug Shannon had purchased at an estate sale, but she predicted it would look bloodier. She disliked herself for basing her expectations on scenes from movies and television shows.

“Wait a minute. Is this real? Is this real?!” Zombie Groom #2 shrieked, burying his face in the Phantom Reverend’s chest.

“Help,” Miss Pierce whispered.

“If it isn’t over in five minutes I’ll call 911,” the Phantom Reverend assured him.

Zombie Bride #1 and Zombie Groom #1 peered from behind a navy blue velvet curtain, as they were due to switch places with Zombie Bride #2 and Zombie Groom #2 20 seconds prior.

Shannon turned off her Ryobi ONE+ cordless chainsaw and mentally reviewed her list of “Dos and Don’ts for College” to share with Kevin before he left for Athens.

Randy Folan remained in the corner chuckling and quietly clapping, resolving to give Shannon a 75-cent raise.

No, Randy thought to himself, adjusting his cummerbund. Make that one dollar.

—

Bobbin Wages runs Hot Dog Beehonkus, a blog comprising humorous, joyful, and gut-wrenching stories about her father’s progression through Alzheimer’s disease. On the more lighthearted side, Bobbin and her writing partner Jason Mallory post collaborative, conversational essays at ameaslygrowl.com. She also performs at literary events in Atlanta such as Write Club Atlanta and Scene Missing: The Show.