After Hurricane Irma battered the South, The Bitter Southerner sent writer Jordan Blumetti to a community in Northeast Florida where, until the last hours, no one expected damage. But the damage came to Middleburg, anyway. There, we met folks with a form of stubborn determination that exists only among Floridians, who “measure out their lives in hurricanes.”

Story and Photographs by Jordan Blumetti

Once the hysteria sets in, we tend to forget that the real problem is not accounting for the gas or the water, but the booze.

Allow me to share a Florida man's experience in the second person: You try to get out in front of the storm by stocking up a week in advance, but then you have a surfeit of booze in the house and a reduced work schedule, and you’re watching a loop of apocalyptic news reports, so you invite some friends over and start drinking while the storm is still a hundred miles from Martinique; and then you’re getting drunker as the menacing eye-wall batters Barbuda; and then Gov. Rick Scott is wearing a Navy hat during a press conference and he’s telling you to evacuate your house, but first you have to Google whether Scott was actually in the Navy; and then you doze off as the storm cruises into the Caribbean, and two days go by and you wake up to see Jim Cantore on the Weather Channel in a helmet and bulletproof vest and can’t believe you aren’t dreaming, so you keep drinking, and by the time the storm reaches the Florida Straits, you’re being told that it’s coming straight up the gut and you’re already out of booze and Home Depot is out of plywood and the only thing still open is the Circle K, but the Beer Cave has been turned upside down, so you buy the last two jugs of rotgut burgundy, and the clerk tells you he can’t break a 50, so you tell him to keep the change.

We, Floridians, have something of a toxic relationship to hurricanes. They provide a great deal of excitement during what are otherwise the dog days of summer. What else is there in late August, or early September, when we’re in “peak” hurricane season? In the sports world, “nothing but the sun-dazed and inconsequential third fifth of the baseball season,” and the likewise inconsequential first Saturday of college football.

We track hurricanes with perverse pleasure. They turn us into amateur meteorologists. They also turn professional meteorologists into amateur meteorologists. (A hurricane might cut us all down to size, but the moment of impact seems like an unexpected nadir for the weather professionals, who are relegated to standing outside in the wind and the rain to tell us it’s windy and rainy.)

Maybe we are spoiled, because the ideal outcome happens to be common in Florida: That forecast cone from the National Hurricane Center casts a crimson shadow over the state, but the storm gets sheared somewhere in the Caribbean or veers out to sea at the last minute, and you end up receiving a fierce, but brief torrent of rain, some downed tree limbs, and an afternoon power outage. You’ve spent days prepping for what ends up being the perfect excuse to drink rum (assuming you have enough), boil hot dogs on a camp stove, and play candlelight Scrabble without any preoccupation except baseline survival — an atavistic fantasy.

The poet and critic (and honorary Floridian) Michael Hofmann believes this perversion is a ritual of American theatrics and spectatorship: Wars, hurricanes, and national championships all “begin as an expensive orgy of logistics and end as a pretext for snacking,” when they should give us pause for other, more existential concerns.

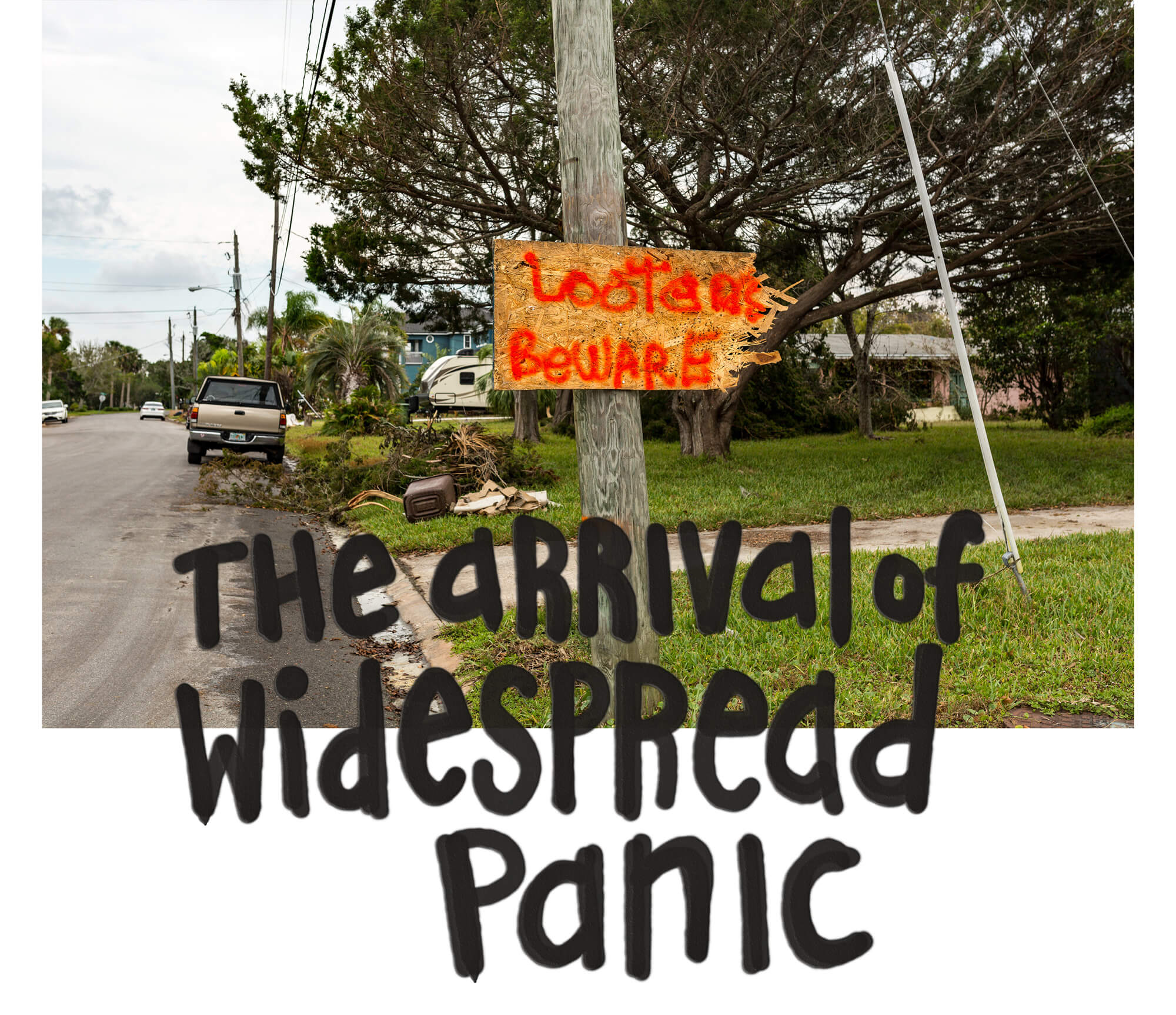

In hurricane season, we can also count on the large base of residents who cannot be made to leave their homes, no matter how perilous the forecast. (And they won’t soon forget the preposterous, sensationalist news coverage Irma received.) Locals don’t leave; leaving is capitulation. They’ll just as soon go down swinging (or shooting, in this case). Holding down one’s fort is a point of pride — a metric of advanced stewardship. “Old Florida hands … measure out their lives in hurricane names,” Hofmann writes. “They remember particular angles of attack, depths of flooding, wind velocities and force measurements, destructiveness in dollar amounts … a form of higher geekishness, each man (and of course they’re usually men) his own survivalist.”

Such folks could not be stirred to evacuate, but their panic and dread were heightened to an exceptional degree this time. Harvey, no doubt, stoked their fears: He wasn't even finished dumping rain on Houston when this giant matzo ball called Irma showed up in the Atlantic. Our memory of these storms and their power seems to reset every few years, but Harvey’s impact was attendant and grimly illustrative.

The Atlantic coast had a week to prepare, and then, after the track suddenly shifted into the Gulf of Mexico, it seemed like the entire state had been boarded up and emptied. The evacuations that were ordered in Miami earlier in the week were now directed at Naples and Ft. Myers — all told, 6.5 million people, one of the largest evacuations in U.S. history. Folks from the Atlantic side had fled to areas that ended up being more dangerous than whence they came.

All eyes were rightly fixed on Southwest Florida and the Keys, which would suffer the brunt. But by dint of counterclockwise rotations, favorable tides, and a storm surge that had apparently been lost at sea, much of the Gulf Coast was spared.

It was Northeast Florida, nearly 400 miles from Irma’s landfall, that left everyone scratching their heads.

The morning after Irma eclipsed the state, I woke up to a video in my inbox of a dude riding a Jet Ski through his front yard. The yard was in Middleburg, on Black Creek, south of downtown Jacksonville. The creek had flooded overnight, up to 30 feet above its normal level in some areas. The water was up to the rafters on his house; the roof of his car breached like a turtle shell.

A few days later, once the water had receded, I drove to Middleburg and found a diner that was starting to fill up around lunchtime. Vaulted ceilings and heart-pine joists held small, lacquered replicas of tugs and ferries. Anatomy diagrams on the walls illustrated the freshwater fish varieties you’d find in the surrounding lakes and tributaries. The only thing that seemed out of place was the flat-screen TV mounted to the ceiling. CMT was playing pop-country music videos. I followed along, then looked out the window at the landscape — soft, inert hills, and meandering country roads bisecting forests of slash and longleaf pine. I thought about how North Florida resembles South Georgia, South Georgia resembles Southeast Alabama and so forth, then looked back at the TV. Those starchy, cloying Blake Shelton videos look nothing like the world they claim to inhabit.

Middleburg is an uncharacteristically hilly region of Florida and mostly dispensed as a bedroom community for nearby Orange Park and Jacksonville. Its boundary is traced out by the path of Black Creek. More specifically, the town sits right where Black Creek splits into two tributaries — the North and South Forks (colloquially called “prongs”) — which travel in opposite directions, in effect creating a moat around Middleburg. Black Creek is a tributary of the St. Johns River — the longest in Florida and one of the few north-flowing rivers in the country. Black Creek’s name derives from its tannin-rich waters, which appear red in the shoals, and black in its deeper channels.

The conversation in the diner rose a few octaves as more people filed in. They exchanged their triumphs and travails, gravid with histrionics and bravado. In their entire lives, they had never seen the creek this high. That part was not an exaggeration, even before their lifetime: The previous record, 24 feet, was set in 1923. Before that, nobody kept score. (The town’s early industries were timber and cattle. In 1864, the 4th Massachusetts Cavalry burned Middleburg down to its foundation. It was resurrected by the citrus boom but then folded again after the freeze of 1895.) On Tuesday, September 12, 2017, points of the north and south prong of Black Creek crested at 30.25 feet. With a typical flood stage of 14.5 feet, Black Creek’s calculus was not favorable.

The waitress came over with a pot of coffee. I asked how she’d gotten along during the storm.

“Fine, just a lot of driving,” she said.

“Where to?” I asked.

She caught a glimpse of my notepad and looked at me askance.

“It’s really not a big deal,” she said, and then began recounting her travels rather absently, holding the coffee pot and staring out the window as I looked up at her chin from my seat. Her name tag read Madeline, with a little hand-drawn smiley face next to it.

At first, Madeline and her family evacuated to Orlando. But they were soon ordered out of Orlando and drove back to Middleburg, packed some more, and left for a campsite near Tallahassee. There, they were told to relocate again and wound up driving west on I-10, all the way to Mobile, Alabama.

“Just you and the kids?” I asked.

“Me, the kids, my husband, his brother, and my mother,” she said.

She moved on to other customers, asking how they fared over the weekend. She spoke loudly, restating sentences, for my benefit, it seemed. Every so often, she’d glance at me and raise her eyebrows, as if to say, “Are you getting this down?” I was.

“The wind sounded like a freight train. I heard it through the walls,” an older woman, aghast, recalled.

“There were little cyclones that came through our yard. Trees didn’t just fall, they were twisted and ripped out of the ground. The next day we found the roof of our back porch all tangled up in some white oaks,” said another, flexing that tacit one-upmanship which comes naturally when comparing traumas.

Madeline handed me a fresh cup of coffee on my way out the door. She told me about a neighborhood down the street that had seen the most water. All the people were nice over there. They’d let me check things out.

At the entrance to Black Creek Hills, I turned down the road that fronted the creek’s north prong and saw everyone out in their yards, heaving furniture and personal effects to the curb. Emptying their houses. Homeowners trudged around their property, their clothes soaking wet, their shanks and forearms smeared with muck. The heaps of drywall and furniture, like the guts scooped from pumpkins, had been growing to heights rivaling the RVs that were parked in nearly every driveway, where the residents had been sleeping.

I was looking for a house that seemed remotely approachable, and it wouldn't take me long. The Piersons were sitting around a few folding tables in the center of their driveway, in the company of several friends and family members. They seemed in high spirits, everyone with a plate of food in hand. On the table, barbecue chicken swam in deep rectangular foil pans. Cans of soda and beer bobbed around in the meltwater of their coolers.

“C’mon, have a seat in the living room!” someone shouted, sending the whole group into a fit of laughter. My own laughter surprised me since I had been steeling myself the whole ride over for a deeply somber affair.

Randy jumped up from his seat and shook my hand. He was a friend of the homeowner’s.

“That’s him, right there.” He pointed to Dave Pierson, who was talking on his cell phone.

“Let’s go. I’ll show you inside,” he said.

More than 100 homes on the creek had suffered major damage, and a good many were destroyed. The Piersons’ house was still in limbo. They wouldn't find out exactly what was covered until the insurance companies, already swamped with claims from Harvey, finally sent out their adjusters to assay the damage.

The house reeked of mildew. Blower fans whirred in every direction. The pine floors were dressed with soiled towels and rugs, resembling crumpled gauze bandages on a profuse wound. We had to lunge over the areas where the wood had buckled.

“Everything was floating in here when they got back — all the furniture,” Randy said. “Funny thing happened with that.” He pointed to a vase. “Once the water receded. it somehow got set down on the counter right where it had been before.”

He showed me the waterline in the living room, a touch over 6 feet, and then took me to the back porch, where I had a view of the creek. The property had 13 feet of land elevation, and then another 10 feet on latticed stilts, but the house had still been three-quarters underwater. He held out his hand while I took a photograph of the exterior. “Did you get it?” he yelled from the balcony, indicating what three stories of water looks like.

A burly man in waders was pressure washing the exterior of the house, the mist blew back and showered us. Then, the gray sky eked out a drizzle.

“Enough already,” Randy said, looking up, squinting through the rain.

Dave Pierson and his wife, Beth, bought the home in October of 2012, the exact week of Tropical Storm Debby, a serious flood event in her own right.

“Twenty-one feet of water — we were told that was the 100-year flood, that we didn’t have to worry because we’d never see nothing like that again. And here we are, five years later, and 8 feet deeper,” Dave said, unable to contain a smile at the sheer absurdity of it. Their house flooded during Debby, delaying their closing on it — certainly a portent. A month later, they moved in anyway.

Things had been destroyed this time, potentially the entire house. But Dave still had the presence of mind to laugh — proof that, in the words of poet Charles Simic, true seriousness and tragedy are inseparable from laughter. I had thought — maybe even hoped — the Piersons would be angry and embittered, harboring some invective for the state, or better yet the world. They weren’t. Losing everything seemed to inspire an almost monastic patience and consolidation. Panic and impetuousness was the track of the pre-hurricane mind. Panic is not often followed by more panic. Even if the worst comes true, a certain liberation follows. A liberation from that compulsion to panic.

The question that remained for the Piersons was whether the insurance companies would be able to honor their policies. Dave turned to his father. “Remember all the companies that went belly-up during Andrew?”

“Yeah, I wonder if these people are really gonna get their money,” his father replied. “That’s the sad thing.”

A deputy sheriff drove by and gave a lazy salute. We waved back. Supplies were pouring in from friends, concerned citizens, family members. A couple days ago, the sheriff’s department set up tents and smoked pork butts for the entire street.

“Black Creek is on the map now,” Dave said.

“I saw on the news that the governor made a visit,” I said.

“Yeah, he was around here somewhere.”

Later in the day, at their local office, I was informed by a few bureau chiefs from the St. Johns River Water Management District (WMD) — a regulatory body managing the water supply and water quality for Northeast Florida — that there has been a legislative plan for the divergence of flood water in Black Creek in the works since 2013. The plan was approved earlier this year, although not in direct response to the two most recent floods. It is simply because the area is flood-prone, and the levels of adjacent lakes, as well as the upper Floridian Aquifer, have been slowly diminishing. Starting in 2021, water will be taken from the south prong and pumped into a recharge facility at nearby Camp Blanding that will slowly replenish the aquifer.

But the level of water extracted, in relation to Irma’s rainfall, is minuscule and won’t address flooding of that magnitude. “It’s just an extremely flashy creek,” said Michael Cullum, WMD’s Black Creek project manager.

The answer to what makes Black Creek especially flood-prone, or “flashy,” is twofold: The nature of the soil at the basin, which is a slick, impervious clay (hence, Clay County), and the topography. There’s a significant gradient in Black Creek, something that doesn't exist many places in Florida. When it rains, the water runs down the soil as it would down the side of a mountain, and the levels go up immediately.

“It’s abnormal, sure, but not statistically unrealistic. People may well call these events 100-year storms, but that doesn't erase the slim chance that they can occur back-to-back,” Cullum said. “The issue with Irma was that for months leading up to the storm, there were record amounts of rainfall, which filled all the groundwater storage, and then you got 10.5 inches of rain dumped on top in 24 hours. There was nowhere else for it to go besides straight up.”

I left Black Creek in the early evening and started for the coast, after hearing from Cullum that a neighborhood in St. Augustine called Davis Shores had also flooded, again.

The only way out of town is through Blanding Boulevard, the main artery of Middleburg, which takes its name from Camp Blanding, which itself was named after U.S. Army Maj. Gen. Albert H. Blanding.

Camp Blanding, first mentioned to me at the WMD office, is a few miles southwest of Middleburg, in a town called Starke (pronounced stark). The name has a noticeable bearing on the town’s physical character.

I made a pit stop at the camp on my way out of town, seduced by a giant C-47 on the front lawn near a sign encouraging civilian inquiries. It’s 73,000 acres, one of the largest joint-military training centers in the country. It also happens to be 10 miles from the Florida State Prison, the state’s largest, an utterly relentless grid of penitential blocks: prisons within prisons, like Russian nesting dolls.

Bill, the tour guide at the museum, told me Blanding was one of the most significant World War II bases in the country, where some 2,000 German prisoners were held, and which, I’m told, had its own Mason-Dixon Line, because Northern and Southern soldiers — 80 years after the Civil War — still couldn’t get along.

On the wall nearest to the entrance hang large photographs of train cars derailed by U.S. troops on their way to Bergen-Belsen.

“Would you believe that I have Holocaust deniers come in here all the time?” Bill asked. He shook his head with contempt. “People from around here, no less. I can usually sense it immediately. It’s disgusting. I just have to walk away from them.”

Bill reminded me that, before last week, the most famous Irma — Irma Grese — was a 19-year-old female recruit from Hitler Youth who became a notoriously sadistic prison guard at Auschwitz. The so-called “Hyena of Auschwitz.” Olga Lengyel represents Irma in her memoir “Five Chimneys” as utterly inhuman — a woman whose violence was psychological, often sexual, and seemed almost supernaturally derived. Of course, there are skeptics, or “Holocaust deniers,” who discredit Lengyel’s account as inaccurate or invented.

Bill seemed to say that the world writ large is divided into these two camps: the deniers and the advocates. He was resigned to apathy, shrugging his shoulders. Even in our brief conversation, I got the sense this was his rhythm of life as a retired high school teacher from Illinois, now running tours at an obscure military outpost where locals stop by just to spout unconscionable propaganda.

He speaks just as disdainfully about his brushes with the local students — kids with no sense of history or geography, he says.

“I recently had a teenager in here on a field trip that asked me if this was where the Vietnam War happened.” He shook his head slowly, agape, in bewilderment. “I mean, you gotta be shittin’ me.”

The bridge into St. Augustine from Middleburg, Shands Bridge, is an old, narrow spanner that leaves what seems like inches between the oncoming traffic on one side and the concrete barrier opposite. The Shands had just recently been reopened. Similar to last year, during Hurricane Matthew, the eastern approach eroded and the bridge was shut down until the county had a chance to inspect it. I drove it, white-knuckled, over the St. Johns River, sneaking glances at the tree limbs and foundered skiffs near the bank. Docks were barely visible. The water lapped over their gangways.

I pulled up to Davis Shores the next morning as the sun finished burning off the previous night’s rain. The scene was similar to the one in Black Creek, though the piles of debris weren't quite as big yet. Up and down the street, Coquina Avenue, just about every home that flooded less than a year ago during Hurricane Matthew had now flooded again.

I found a husband and wife, Roy and Ann, outside on their front porch sitting on coolers. A brick, single-story house on the marshes alongside a stretch of the Matansas River. I could see the waterline two or three feet above the threshold of the front door. Each house still bore the same marking left by the thin layer of sediment that had risen to the surface. Five days since the flood, but the water lines remained. They reminded me of the lamb’s blood from Exodus, some apotropaic ritual intended to ward off further destruction.

Ann gave me a chocolate chip cookie and suggested I have a seat with her and her husband Roy. The flooding was worse last year, she said, and it was their first time dealing with it, so they were much slower to start the process.

“A terrible, terrible process,” Roy said, referring to the insurance company, the bank, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and, of course, scrapping your life into a pile in the front yard.

They moved back in at the beginning of March, which gave them about six months in their newly renovated house. They’re now sitting on their doorstep eating sandwiches and watching it all get chucked away.

“We’re ahead of where we were last time. We’ve kinda got the system down now so it’ll probably go faster,” Ann said.

Unfortunate as their situation was, they could not simply move, not with a mortgage. And they couldn't tear the house down and rebuild at a higher elevation unless the insurance company pays for it, which was unlikely.

“This time around I’m almost more heartbroken. But we’re moving much faster, and I feel a little bit better. I do have moments where I wonder if I’ll be able to do this until the very end, or do I want to?” Ann narrowed her eyes and let her head fall slightly. The words seemed to mystify her.

With Irma, just as last year with Matthew, it was heavy rainfall, an unanticipated storm surge, and unusually high tides due to the lunar cycle that flooded this low-lying coastal area. True, the recurrence of these floods is something of an anomaly, but I was reminded at the Water Management District office that in 2004, there were four storms: Charley, Frances, Jeanne, and Ivan — all of which compounded grievously — followed by 12 years of relative quiet.

“If you live in Florida, sooner or later you’re going to face a storm of some magnitude. It’s part of the natural order.” That was the bottom line, according to the WMD. And they called upon the records of Spanish Florida to illustrate.

But in relation to the recorded history of Columbus and the New World (which aptly begins in St. Augustine, the first permanent settlement in North America) 12 years is a negligible hiatus.

According to an exhaustive compendium arranged by José Carlos Millás, there were 306 hurricanes — or furacanos, as they were first called by the Spanish — recorded from 1492 to 1800, of which only about 5 percent were said to have significantly affected the Spanish province of Florida. It wasn't until 1811 that St. Augustine had its first documented bout with a hurricane, amid bankruptcy and a looming war with the Georgians, one month after the city’s 246th birthday.

The entire city had been destroyed. “The greatest damage was caused by flood water, a killer wave known in modern terminology as the storm surge,” historian Sherry Johnson writes in her essay on the subject. But, “What [should have been] a total breakdown of civil and military society in Spanish Florida after the hurricane of 1811 did not happen.” Instead, the city was rebuilt, albeit briefly, under the Spanish Crown.

Juan José de Estrada, the interim governor of Spanish Florida, said of his residents, “[They] are entirely ruined but [they] have managed to survive with a great deal of patience.” Maybe this brand of patience is salient throughout all communities in times of recovery, but with this report from Spanish St. Augustine, there seems to extend a legacy of fortitude that Floridians have an obligation to uphold if they have any shot at posterity. The patience I had witnessed was not an isolated incident, but a function of where this state’s people choose to live, a case study of how environment begets personality.

Here was the lesson: Try to get lucky, take your hits when they come, rebuild when you have to, at least until the day you don’t have the resources, or strength, which Ann already seemed to anticipate. Beyond that, no one’s probing anything deeper. There's too much work, too much swollen drywall that needs to be ripped out.

“At least, we have power. A lot of people around here still don’t,” Ann said before I left her and Roy. She was finding solace where she could.

While it seemed like only a trifling dilemma in relation to what I’d already seen, the power situation turned out to be the one that bedeviled Floridians the most. It certainly made them angrier than anything else. And not for nothing: It was responsible for 12 deaths in a Miami nursing home.

On Friday, five days after Irma hit, the boulevard on Anastasia Island, Davis Shores, and a few other pockets of St. Augustine were lucky enough to have their lines repaired. But the majority of homes on the island were still without power. The number of statewide outages peaked at over 4 million, for close to two weeks in some counties.

After my visit to Davis Shores, I pulled into a gas station on the boulevard to pick up some rations. A pair of Volkswagen conversion vans were parked out front. Both were early ’70s Vanagon models, pedantically restored. A group of kids was dawdling in front of the open panel doors. One of the vans was painted a lustrous, old-world taupe, and underneath the back window, in scrolling green letters, it read: “There ain’t no rust on the happiness bus.” I found it a tad uncouth, considering the presently incalculable amount of property damage all around me, but not much of a surprise, really — it’s a hip area, and hipsters are often tone-deaf.

Inside, the beer coolers were being picked over by a hive of shaggy-haired bohos that looked conspicuously affiliated with the flower children in the parking lot; I sensed something was on the wing, but I grabbed what I needed — a few jugs of water, beer, Rold Golds — and set it on the counter without a second thought. Beside the checkout line, I noticed a refrigerator packed with cold cuts. Two strips of yellow caution tape were crossed in the front of the unit.

“How’s it going?” I asked the cashier, reaching for my wallet.

“Pretty good for $8 an hour.”

I nodded. I wanted to ask a followup about the cordoned-off meats, but his response was too brusque to warrant further dialogue. Any remaining questions as to why they hadn't emptied the refrigerator, I found the answer right there in his wage.

On my way back through the parking lot, I walked past the vans. Another one, less pretty than the others, had shown up. I offered that obligatory nod of approval. They nodded back. I stopped.

“Hey, what’s going on? Some kind of car show?”

“Nah, man. Panic’s in town!”

He was not referring to the emotion, which would have been an appropriate, if not oversimplified response to those people down the street who were faced with physical (and in some cases financial) ruin. He was referring to Widespread Panic, the inveterate, incessantly touring, jam-band progeny of the Grateful Dead.

Panic’s annual three-day run at the St. Augustine Amphitheatre — when the town is inundated with the band’s fanatical devotees and bloodshot zealots — happened to be the weekend following Irma, when insurance appraisals were just getting underway and the power outages were still (forgive me) widespread. But a day before the concert was set to begin, the city managed to restore power at the amphitheater, and, to the extreme consternation of most residents, the band announced that the shows would go on as scheduled.

Later that evening I was invited to a barbecue. Another in a long line of cookouts I had been to that week. Jim, a local contractor, and his wife Amanda, who teaches middle school, were hosting for their cul-de-sac, which happened to be within earshot of the amphitheater. Since the power went out, everyone on the block had been emptying the meat out of their freezers. There was no other recourse to stop the food from spoiling. Pounds of it already thrown away, and had been stewing in plastic trash bins yet to be collected. The smell, a distinctively Third World aroma, was growing more intolerable with every passing hour of sunlight.

The wind was slack and the moisture from all the precipitation still hung in the air. The heat — the utter stillness and density of it — was subtle, and preluded a creeping madness.

“I’ve been sleeping on the terrazzo all week,” Jim said. “Well, not sleeping, obviously."

Sleep was hard-fought, with the heat charging the walls all day long, peaking at 100 degrees, and then slowly radiating back through the house at night. There was a time, before central air-conditioning, when construction in Florida accounted for climate, when houses stayed cool in the summer and warm in the winter. That provision now seems to be flipped on its head. Losing power transports us to somewhere primitive, though, if we had truly arrived at a more primitive moment in Florida, chances are we would have found intelligible vernacular architecture — the cracker farmhouses from the early pioneers and homesteaders to the late transplanted carpetbaggers — that provided more inhabitable temperatures by manipulating shade and augmenting air movement. We seemed to have gotten lost along the way, shedding those “regional peculiarities” that gave rise to simple, unpretentious construction with more emotional and pragmatic grist than all of the stucco eyesores from South Beach to St. Mary’s combined.

Consequently, there was virtually no reason to be inside so everyone just shuffled up and down the street — the autopilot of bodies that were at once exhausted and restless. They were shirtless or in bathing suits, sweating, trying to remain vertical long enough to have a shot at collapsing once the sun went down. And when the sun did set, save for the headlamps, it was unconditional, primordial darkness that descended, and the generators echoing through the trees all night only exacerbated the sense of being locked in the gears of a fever dream.

But, for now, the sun was still hovering over the Matanzas River, highlighting the magnolias. One of the neighbors, a local ER doctor, had been smoking a venison shoulder all day — what remained of his cuts from last hunting season. Also on the menu was some deer sausage and the last of Jim’s lobstering haul from the Keys.

“I get it,” Jim said, buttering some tails. “It’s good that money is being pumped back into the city this weekend. But shit, a couple more days of this and my house is gonna start molding.”

A large portion of the older demographic had begun drafting strongly worded letters that were just as soon abandoned after realizing they had nowhere to send them. But their situation was demonstrably direr, and Jim recently had to install free-standing AC units for a few elderly couples on his street. The units were on loan from the city — their response to several 911 calls from senior citizens who complained of heat exhaustion and heart palpitations.

He told me that Florida Power & Light, and the city, released a statement indicating that they were prioritizing restoration efforts in places of business and congregation ahead of individual neighborhoods, but he also went through pains to say this was second-hand information.

“We’ve been in the classic, high-stress, rumor-mill situation for weeks now,” Jim said. “I don’t know what to believe anymore. But I quit being angry about it. I’m not gonna be just another guy in Florida who’s mad at the government.”

The first few guitar notes pealed from the Amphitheatre, and a spirit of repose settled over the backyard. Everyone stopped and listened.

It wasn’t the end of the world, not yet. But when the time does come, I suspect we’ll be able to count on Widespread Panic to be there, playing us out, like the quartet on the Titanic.

“Somebody is definitely huffing nitrous in a port-o-potty right now,” Jim said, after a verse. “What a world.”

He lifted the lid on the kettle grill with one hand and flipped the sausages with the other. Amanda walked around the backyard and passed out some paper plates.

This was how a Florida Man is made — the good kind, not the one from Twitter — and I have the pleasure of knowing many: His sense of humor is in fine shape; he may have stayed home during the hurricane, but he wasn't asleep; he is forged in the subtropical heat, unmoved by the acrid smell of steaming refuse; he takes care of his neighbors; he is languid at sundown and up early with coffee, because he is eager to learn, and he learns from everything, especially his wife, but he never thinks more than he has to.

And when a problem comes his way, he throws barbecue at it.