The Folklore Project

Atlanta, Georgia

A Dress of Leaves

By Ron Huey

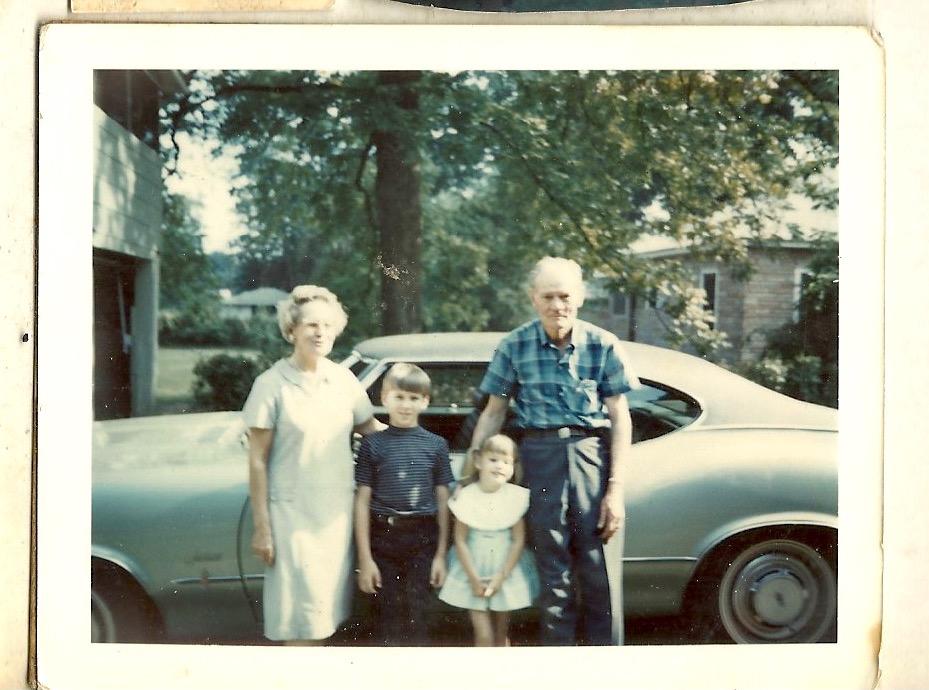

Milton and Margret Gilmer were people of hard lives, but soft hearts. In my earliest years, they were caretakers for me and my cousin, Scott, while our lives innocently unfolded in the small town of Austell, Georgia.

Each morning, my parents would start off for work while I watched from the safety of Margret Gilmer’s arms. A sweet lady whom I would come to call “Gigi” as I grew older. My earliest memories of life with the Gilmers are hard to recollect. Maybe I was too young, maybe too much time has passed between then and now. Regardless of which, I look back on those days with a smile as wide as the slices of pecan pie Margret was known to serve up.

Milton Gilmer was a man stained with years of sweat and hard work. He was a man who made ends meet. As long as I knew him, he was a lawn-mower mechanic. Milton was tall and slender with a bit of a hunched back. Years of digging through screws and bolts and pipes and blades will do that to a man. I always picture Milton covered by a thin layer of grease. On his work clothes, always on his hands, sometimes on his face. A face that held eyes of pure blue and was carved with deep crevices adorned with gray stubble.

When I grew tall enough to toddle, I would spend my afternoons at Milton’s side in the small work shed behind their home. The shed was a wild and wonderful world. Its floor was rich with the dark, spilt blood of Milton’s mechanical patients. Tools lay like fallen soldiers across the counter. Abandoned springs and washers found refuge in the shadows and among the empty boxes. And the smell of cigarettes hung in the air like a drape.

At night, I would help Milton push the lawn mowers inside for safekeeping. Then, I’d chase his heels up the back steps into Margret’s kitchen to a waiting plate of fried chicken, white butter beans, or, if we were lucky, fried okra. The Gilmers could not afford fancy, cloth napkins. But they were much too dignified to use paper napkins. As a compromise, they used small kitchen towels. Something between fine linen and a dishrag. More on the dishrag side. The Gilmers were simple, but proud.

In the Gilmer home, discipline wasn’t handed out easily. Not that I was a child who particularly needed much. For me, their love ran deeper than the oil stains on Milton’s coveralls.

Early one evening, Mom returned from work to find Margret in the kitchen. The usual warm, inviting smells of dinner filled the air, but something was amiss. Mom’s eyes scanned the room for Milton. Maybe he was out back finishing up in the work shed.

Margret offered no explanation, only stared into the simmering grease of her skillet. Turning for the back porch, Mom’s steps were met by Margret’s soft plea, “Don’t go out there,” her eyes never straying up from the pan.

“It’s Milton,” Margret continued. Mom’s heart stopped.

Margret’s head hung like a two-ton anchor, but she struggled on, her voice frail and measured. “Milton had to spank Ronnie.” Mom turned her sights to the porch. There, under the thin veil of darkness, a 70-year-old man stood quietly. Tears silently stole down the long, deep crevices of his face, fighting their way between the gray stubble. Tears his pure blue eyes and huge heart could not hold back. It still hurts me to think about it over 50 years later.

The Gilmers were guardian angels in the most modest attire. There was nothing they wouldn’t do. Mom recalls a late autumn afternoon when she called Margret to catch up on the day’s activities. Margret’s voice, with the exuberance of a woman half her age, exclaimed, “We’ve been playing hide and go seek in the yard!” She then explained how she had buried herself, toe to head, in a pile of leaves, leaving me bewildered and at a loss for her whereabouts. She laughed in a pitch that must have startled Milton from his afternoon nap in the porch-side rocker. Margret in a dress of leaves. It’s amazing what 65-year-old bones can do when they want to.

By 1969, my family had moved to Winder, a small speck of town, about an hour northeast of Atlanta. But in the summers, my cousin Scott and I would return to visit the Gilmers. For us, it was summer camp. Two solid weeks of helping Milton in the shed, Margret’s mouthwatering meals, and endless mischief. The Gilmers were just too kind-hearted to keep us on a tight leash.

For young boys like Scott and me, racing bikes was fun, but racing riding lawn mowers took fun to another level. There are a few things you learn when you’re a rookie riding a racing lawn mower. First, for optimum speed, run with the blade up instead of down, whirling beneath you. The fact that this was also much safer wasn’t really the issue. Second, be wary of 90-degree turns. A thin 9-year-old body is rarely an adequate counterbalance for 200 pounds of steel and hot oil. Early in our racing careers, we were forced to bail out of many an errant ride.

With the day’s races behind us, we’d climb into Milton’s aging blue Volvo for a trip into town. The Volvo was Milton’s “work car” and stayed parked in the side yard, like an old mule tied to a fence post. It was essentially a rolling tool box and fit Milton’s specifications precisely. There was a place for his coffee between the seats. A small ashtray that was always overflowing with cigarette butts. The seat covers was ripped here and there, allowing the yellow foam beneath to peak out from between the springs, like prisoners from a cell.

Like everything Milton touched, the Volvo was covered in grease. That fact alone caused Margret to keep her distance. When you live on lawn mower mechanic’s salary, you can’t afford to soil too many dresses.

Scott was technically my third cousin, and my summer trips were as much about seeing him as seeing the Gilmers. We’d walk into downtown Austell to the Unique Market. Along with a Popsicle or Nutty Buddy to cut the summer heat, we were always sure to grab a couple of bags of balloons. You might ask, “Just how many balloons does it take to occupy two 9-year-old boys?” More than you might think. Because these balloons were not meant to carry air, but water.

In the South, we have faucets indoors, but we have spigots outdoors. The Gilmer’s spigot came out of the wall just under Margret’s kitchen window. That spigot carried an ocean of water into our waiting balloons. While throwing water balloons at each other was fun, throwing them at passing cars produced the real thrills.

Remember, mischief was always the call of the day.

Like lawn mower racing, there were a few things you learned about filling water balloons. Overfilled balloons tend to implode when confronted by the sudden, forward thrust of a small 9-year-old hand. The optimal size was more like an apple. Something we could easily grasp. Something that would most likely find its target. The Gilmers’ side yard was lined with a thick hedge providing the perfect cover for a pair of midget snipers. Grenades of every color came crashing down upon our enemy. A rainbow of terror sent from the gods above. Fords, Chevys, Barracudas and more all met their watery fate.

Our time with the Gilmers was never long enough. We could stay a week, a month, an entire summer. The Unique Market would never run out of balloons. And when the day ran out of sunlight, we could park the lawn mowers and retreat inside for Margret’s cooking. Year after year, summer after summer, we’d return. But as we grew taller, Margret and Milton grew older. For them, life was winding down.

It was 1973 and I was 13 when Dad got the call. Margret’s solemn voice carried the news, “It’s Milton,” she said with quiet resignation, “He’s dying.”

The concept of death was foreign to me. I had only heard of people dying, and my naiveté shielded me from death’s cold reality. But Dad and Mom knew. We crowded into Dad’s 1972 Volkswagen Beetle and started out for Austell. And for Milton.

We pulled into the Gilmers’ driveway over thousands of lawn mower tracks and millions of tiny footprints. We pulled in beside the spigot that had filled a carnival of balloons. We passed just below Margaret’s kitchen window, and the Volkswagen came to rest in the ghost of rusted out Volvo. I followed Mom and Dad up the porch steps. I didn’t want to go in. I didn’t know death and didn’t want to.

We knocked on the door and cautiously made our way into the kitchen and slowly down the hallway. We saw Margret with a heavy heart and a tear-streaked face. She managed a small smile. Then we saw Milton.

Milton lay, literally, on his deathbed. A black veil of cancer gripped his lungs, and his frail hand gripped mine. What were once hands of stone were now weak and fragile. Milton’s pure blue eyes had grown cloudy. A thick cover of stubble crept across his thin face like gray kudzu. The light from the window was soft and quiet, and a well-worn white blanket lay over him.

I don’t think I cried then, but I do now. I didn’t understand cancer. I secretly hoped that somehow he would get stronger, better. Milton knew he would not.

“Son,” Milton’s voice struggled. I leaned closer so that his words might more easily reach my ears. Milton took a long, whisping breath and gathered his thoughts. “Whatever you do, son…don’t ever smoke cigarettes.” His voice was thin and raspy. I didn’t quite understand. Milton fought to take another breath and better explain his point: “They’ll kill you.” Milton craned his head forward as his eyes felt for mine.

As Milton spoke, he would pause and close his eyes. He was exhausted, running on fumes. Angels hovered over his bed waiting patiently for our conversation to end.

Milton’s strength was gone, and Dad told me we should go and let him rest. I agreed. Milton was too weak to even muster a smile. He was ready. I kissed him goodbye and gently lay his hand across the worn white blanket.

The sky was a deep, crystal blue as a steady stream of people filed into the First Baptist Church of Austell. Bells rang and little old ladies had to be helped up the front steps. Old men shook hands and talked about old times and spoke fondly of Milton.

Inside the church, a river of flowers poured out in every direction. All around the room. All around Milton. A line had formed and slowly crept its way beside the coffin. Mom and Dad and I joined in to say goodbye for the last time.

When my eyes met Milton, he was as still as a hot August night. Like a deep, dark, peaceful sleep had filled him. He looked just as he had when I’d left him in Margret’s bed. Only now he was quietly smiling. It was OK.

The preacher talked about what a gentle and kind and strong man Milton was. Everyone agreed. He talked about Margret and what a good wife she had been. Everyone agreed. A choir sang “Amazing Grace,” and I like to think Milton listened with approval. Tears could not be restrained. They were quiet tears. As quiet as the ones that had gathered on the Gilmers’ back porch after the spanking so many years earlier.

The preacher added some final kind words about Milton, and the service concluded. People rose and slowly made their way for the doors, exchanging pleasantries. Scott and I stole our way out a side door of the sanctuary. We stood alone in the church parking lot until the last of the cars faded from sight. The sky remained blue, but all else gray.