Kentucky Gets Hip to Hemp

The Agricultural Act of 2014 allowed certain states to start farming hemp again after a ban of almost 60 years. One Southern state has already established a lead in the race: Kentucky. It will be years before we know if hemp can replace a significant portion of the income lost with the disappearance of tobacco and coal revenue, but that isn’t stopping a diverse gang of Kentuckian entrepreneurs, farmers and manufacturers from staking their futures on it.

Growing hemp in Kentucky means something different for everyone who does it.

For Jake and Andy Graves, father and son businessmen in Lexington, it means winning the battle for legalization they have been fighting for decades. For Joe Schroeder and Lora Smith, husband and wife farmers, it means a time for small-scale experimentation.

For Alyssa Erickson and Kirsten Bohnert, the “Kentucky Hempsters,” it means using their talents to reshape perceptions of central Appalachia. For Mike Lewis it means putting veterans back to work. For Stephanie Brown, a weaver in Louisville, it means bringing an old textile design to life in a new way. For David Williams, a professor at University of Kentucky, it means incredible scientific access to research a crop that has been illegal for his entire life.

For Todd Howard, a Community Supported Agriculture founder and small-scale farmer in eastern Kentucky, it means transforming abandoned mine lands into farmlands. For Carolyn and Jacob Gahn, owners of Sweetgrass Granola, it means providing healthy and homegrown foods to customers.

While each of these folks is gravitating to the industry for his or her personal reasons, what brought them together is Section 7606 of the Agricultural Act of 2014.

On Feb. 7, 2014, the bill was signed into law. It authorized five-year pilot programs through universities and state departments of agriculture. Currently, 26 states (including several in the South) have been approved to grow industrial hemp: some for research, some for commercial value. For the next four years, hemp can be grown and processed to produce fiber for textiles, paper and building materials, as well as seed and oil for food, beauty products, biopharmaceuticals and fuel.

But all eyes are on Kentucky, where bipartisan support led by U.S. Sen. Rand Paul, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Kentucky Agriculture Commissioner James Comer has made the state a leader in industrial hemp production. Farmers across the state, many of whom once grew tobacco, are planting some of the first hemp seeds that have been grown in this country since the crop was banned nearly 60 years ago.

The Kentucky State Department of Agriculture has licensed more than 100 programs at universities, private farms and processing sites for the 2015 season. Kentucky's industrial hemp pilot programs have dramatically increased since last year; 121 participants, including 24 processors, are participating this year. They expect to plant 1,742 acres this year, compared to 33 acres in 2014.

Leaders across the country are looking to the Bluegrass State for answers, hoping to learn from its successes and failures so they can eventually make hemp part of their own economies. It’s an exciting time for experimentation, but with only five years secured for the pilot sites, farmers are feeling the pressure to prove hemp can be part of central Appalachia’s economic transition.

“I hope that the politics hold regardless of the shifts in administration and that folks will give it a good solid try,” says Joe Schroeder, CEO of Freedom Seed & Feed, a farming company that calls itself the “first federally permitted hemp farm” since the ban. “It will take us a few years to get to the point of understanding how we can benefit the farmers in the state, because we have a lot of farmers that need help.”

Atalo Holdings' 27 acres of cannabinoid-rich hemp plants in Winchester, Ky.

When you talk to Kentucky natives about the crop, their words drip with nostalgia. That’s because hemp and Kentucky have had a close relationship in the past. The return of hemp to their soil could be likened to the arrival of a long-lost cousin.

“It keeps me going knowing that there’s this plant out there that can do some many things,” Kentucky Hempsters’ Alyssa Erickson says. “I’ve been called somehow to bring it back to its home.”

For Kentucky, for Appalachia and for small-scale agriculture, hemp could be another step in the move away from the mono-economy of coal, a volatile industry that is everything hemp is not: single-use and dirty. Hemp roots are literally pulling these mountains back together, bringing hope for farmers and the entire region. Whether it fulfills that hope remains to be seen.

“The region is in a tailspin and people are trying to figure out what to do next,” says Lora Smith, co-owner of Big Switch Farm in Egypt, Ky. “I don’t think it’s going to be one industry that will take over, but there has to be lots of little things, and I see agriculture, and hemp, as being one of those puzzle pieces.”

“I am very glad to hear that the gardener has saved so much of the st. foin seed, and that of the india hemp. Make the most you can of both, by sowing them again in drills. The hemp may be sown anywhere.”

— George Washington, in a letter to William Pearce, Feb. 24, 1794

Hemp seed and fiber once played a vital role in America. It was such an important crop that in 1619, the Virginia Assembly passed legislation making it illegal for farmers not to grow hemp. Founding fathers George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were also big fans; they grew hemp. So was Henry Ford; he made a car out of hemp.

Kentucky farmers first grew hemp in 1775. The state went on to lead the nation in hemp production in the mid-19th century, producing 40,000 tons in 1850. Scores of factories made twine, rope, parachutes and bags for cotton-picking. Like tobacco, cotton and other big-volume crops produced in the 19th century South, hemp demanded manual labor, much of which was provided, under duress, by slaves and later their descendents.

But in the 1930s the line between hemp and its cannabis cousin, marijuana, began to blur. “Reefer Madness,” a propaganda film and campaign, spread widely. Images of crazy-eyed, suicidal and promiscuous pot smokers filled the newsreels warning people of the dangerous effects of marijuana. In 1937, the farming of low-THC hemp became illegal along with its wacky-tobacky cousin, marijuana, when Congress passed the Marijuana Tax Act.

Hemp advocates have long struggled to change the public perception of hemp. In 2012, Colorado legalized cannabis and defined hemp as “a plant of the genus cannabis … containing no more than three-tenths of one percent of THC.” The .3 percent level of THC has been accepted across North America as one of the defining differences between marijuana and hemp.

So since it’s been determined that hemp must only contain 0.3 percent of THC or less, what does that mean for marijuana? In Colorado, studies have shown the average legal marijuana is 18.7 percent THC, but levels can reach up to 30 percent in high-potency strains. There’s clearly very different levels and properties of THC in the two plants.

“Most people have this idea that hemp and marijuana are the same thing,” eastern Kentucky farmer Todd Howard says. “If we can start having the distinction between the two, I think it will catapult the industry into a completely different realm.”

During World War II, hemp had a short comeback. From 1942 to 1946, farmers across the nation grew 150,000 acres of hemp through the USDA’s “Hemp for Victory” program. But in 1957 the final hemp crops were grown as new government incentives supported plastics over natural fibers, and the crop resumed its illegal status.

Farmer, veteran and advocate mike lewis

It’s hard to believe that just two years ago, Mike Lewis didn’t know much about hemp. Today, his bearded face has become the symbol of hemp advocacy in Kentucky.

He had spent most of his recent career advocating for small-scale and sustainable farming as the executive director of Growing Warriors, an organization that helps veterans transition back to civilian life as farmers. It’s a personal mission for Lewis, who served in the “Commander in Chief’s Guard” of the 3rd U.S. Infantry from 1992 to 1995, as well as his brother and fellow veteran, Fred-Curtis Lewis, who is the organization’s service director.

But after getting involved with hemp advocacy in 2013, Lewis met some folks from Fibershed, a company whose goal is to help foster resilient, community-organized textile cultures and collaborations between rural and urban areas. He looked around and saw many small, struggling family farms that once grew tobacco. So last year, Lewis founded Freedom Seed & Feed and planted two acres of hemp on old tobacco land. “It was the best looking hemp crop in the country,” he says with pride.

That allowed Freedom Seed & Feed to do research and development, create test products and grow the crop with veterans. But it wasn’t without challenges. During the first pilot year, the federal Drug Enforcement Administration seized 250 pounds of hemp seeds en route to the University of Kentucky from Italy. The State of Kentucky fought the DEA and a court ruled in favor of farmers.

Even after the seeds were planted, Lewis and other farmers witnessed black helicopters looming over their fields, the DEA's own rudimentary spy drones. Out of a 90-day growing season, the helicopters circled his farm at least 80 days, Lewis says. He adds that the state government is on the side of hemp growers. He credits James Comer, the commissioner of the Kentucky Department of Agriculture, for leading the Bluegrass State forward on the issue.

“James is a farmer, and he knows what the loss of tobacco did to Kentucky farms,” Lewis says. “He saw that hemp wasn’t what it was painted to be. It’s a crop with a ton of potential, and he sees the potential.” That potential is widespread. Hemp is the Swiss Army Knife of plants, boasting a wide array of uses within its thick fibers. Unlike its slow, one-trick-pony cousin, hemp can be transformed into products for many markets, including food, textiles, fuel, body products, building materials and biopharmaceuticals.

Countries all around the world are benefiting from hemp economies, including China, Canada, Germany and Australia. Most hemp fiber for textiles is grown in China and Europe, with China in the lead. Since 2004, German-based automaker BMW has been using hemp-based composite door panels in their 3 and 5 series vehicles. Most of the hemp fiber, seeds and other products imported to the U.S. come from Canada.

“All the other industrialized nations allow for hemp cultivation,” says Eric Steenstra, executive director of the Hemp Industries Association, a nonprofit industry group that has fought for legal hemp farming since 1994. “America is the last one to the party.”

In 1998, the U.S. began importing food-grade hemp seed and oil. Three years later, the DEA attempted to make it a federal crime to consume, possess, distribute or sell hemp products. The agency issued an “interpretive rule” banning hemp seed and oil food products that contain any amount of residual THC. Your favorite crunchy granola and hemp body lotion were yanked off the shelves. Lucky for you, the 9th Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals overruled the DEA.

Despite the illegality and following suit with most black markets, hemp sales have continued to thrive. During the past six years, hemp food and body product sales have grown at a 20 percent rate. In 2014, retail value for hemp products sold in the U.S. was $620 million, according to a March 2015 report by the Hemp Industries Association.

In one year, Lewis’ Freedom Seed & Feed went from digging in the dirt to talking to investors. In February, Freedom became a wholly owned subsidiary of publicly traded Mountain High Acquisitions Corp. The capital infusion allowed Freedom to expand its planting from two acres last year to over 100 acres spread across six farms.

Four of those acres inhabit former strip-mining land in Pikeville. Pikeville, on the eastern side of the state, has a rugged landscape marked with steep mountains and deep valleys. These are not the flat, rolling tobacco lands of central and western Kentucky. In an odd twist of fate, reclaimed mountaintop-removal sites — relics of the coal industry — provide thousands of acres of flat farmland, even though the geography of eastern Kentucky, pre-strip mining, wasn’t exactly hospitable to crops like hemp.

~ Reclaimed Mine Land, Pikeville, Ky. ~

This year, Freedom Seed & Feed funded the Institute for Regenerative Design and Innovation (IRDI) at the University of Pikeville. The institute engages students from UPIKE to research industrial hemp production in the coalfields. Fifteen students from IRDI helped Freedom Seed & Feed prepare the strip mine in Pikeville for planting hemp. They worked with Nathan Hall, Todd Howard and Eric Mathis, the founder of the IRDI, to clear large boulders and rocks from the former blasting site. The team had to also take into consideration potential contaminants, such as heavy metals and toxins, in the former mine site’s soil.

Mathis, founder of the IRDI, says students are leveraging the region’s biodiversity by identifying a variety of plants in central Appalachia that have medicinal applications and then blending them with the CBD properties of hemp. He’s referring to CBD oil, a product of legal, low-THC hemp that some scientists call a miracle drug. Other than biopharmaceuticals, students are also exploring regenerative design using hemp for building materials.

Eric Mathis, founder of the IRDI

“Building on the back of industrial hemp, we’re leveraging the potential that industry has with two of the most valuable assets in central Appalachia: its people and its biodiversity,” Mathis says. “We’re wanting to usher in a completely new way of understanding economic development. The traditional economic lens that businessmen saw the region was through natural resources; salt, timber, coal. But that’s a fairly homogenous lens for viewing the potential of any region, especially one of the most biodiverse regions in the world.”

As a plant, hemp is resilient, independent and can thrive in a variety of environments, wet or dry. Unlike cotton it doesn't need to be pampered with lots of herbicides, pesticides and daily water. Give it some soil, a bit of sun and rain, and hemp will grow like the weed that it is, giving the cultivator its bountiful yield. Hemp strains for fiber can take as few as 60 days to reach full growth, making it a great rotation crop. Despite hemp's hardy growth, invasive plants used in mine reclamation are standing their ground.

Nathan Hall holding lespedeza and fescue on the Pikeville site.

“Invasive plants are not very nice to native species as far as having a diverse ecosystem,” says Nathan Hall, a young entrepreneur from Kentucky who studies and works to reforest mined areas in Appalachia. “So you end up with his ubiquitous situation across strips mine lands of Appalachia where you have seas of lespedeza, fescue and autumn olive.”

Schroeder, CEO of Freedom Seed & Feed, said they learned alot about growing hemp in a barren, rocky place, and unfortunately they don’t see hemp cultivation on strip mines as a viable business option. Nonetheless, the hemp that did beat the weeds and the rocky soil this year will be harvested and used in research and development projects with FiberShed.

Farmer Todd Howard wonders if hemp can revitalize his hometown of Hippo

When Todd Howard isn’t planting hemp on former strip mines, he’s growing vegetables and tending to hogs in the deep hollows of eastern Kentucky’s Floyd County. With help from his business partner and family he has started one of the first successful CSA programs in the coalfields, and he has great aspirations for how agriculture can bring back the economy of his tiny community, Hippo.

Howard got involved with hemp just as a curious farmer and advocate for diversifying the economy. As a father of three, he feels it’s his responsibility to contribute to the transition economy in the coalfields.

“Now that we have three kids it’s more and more important for us to be a part of the transition movement,” Howard says. “I don’t know if they will ever want to live here, but I don’t want them to use the excuse that so many of my friends and relatives had to use: ‘There’s nothing here.’ As parents, we have to do our job. It’s not only raising our kids, but it’s providing opportunity and leaving this world in better shape than we found it in.”

Big Switch Farm is located in the southeast corner of Jackson County in the foothills of Kentucky, where the Appalachian Mountains meet the bluegrass. The county has small-scale farms and a dwindling number of coal jobs, but it’s not a coal-dependent county like its neighbor, Clay, and has not seen large-scale farming like in western Kentucky. Here, Freedom Seed & Feed CEO Joe Schroeder is seeding his first field on Big Switch Farm. He fills his tiny push seeder with hemp seeds. His daughter, whom he and his wife, Lora Smith, lovingly call “Biscuit,” is plucking out the seeds from the basket, quietly murmuring “turtles,” while admiring the tortoise-shaped seeds. He starts down the field, getting stuck on clumps of dirt along the way.

Schroeder and Smith bought their family farm in 2010. They have dreams of making the organic farm their home and source of income. This year, Smith and Schroeder are growing Appalachian heirloom crops, like tomatoes and peppers, but also several acres of hemp. The test plots will answer questions about the feasibility and profitability of small-scale hemp production.

“We are very committed to being in this region,” Smith says. “We want to figure out how we can raise a family doing this. I have a lot of optimism that hemp is going to be part of what allows us to do that.”

~ Big Switch Farm in Egypt, Ky. ~

The Big Switch plots are designed to understand the potential harvest for hempseed for the food market, and hemp fiber for clothing and paper products.

“I’m just constantly blown away,” Smith says. “I’ve never been in a position where you are seeing the potential birth of an industry. there’s no road map for this. But our interest is bigger than us making a living. I’m motivated by finding out how can other families in Eastern Kentucky make a living off of this.”

Schroeder estimates the Big Switch hemp test plots could provide $4,000-5,000 an acre. That profit includes, harvesting and selling the seed for approximately $1,000 and then selling the rest of the plant for other products — leaves and matter for paper, fiber for clothing and the hurd for hempcrete or bedding for horses.

~ Watch Joe, Lora and Family on Their Farm ~

Rebecca Burgess is founder and executive director of Fibershed, the California company that acts as a broker between hemp farmers and fiber purchasers. Burgess says an acre of hemp produces upwards of 4,000 pounds of textile and cordage fibers, while one acre of cotton yields only 2,000 pounds.

“I think hemp offers so much; because of its biomass-dense form, it allows a lot of material to come off of one acre,” she says. “You can get more garments per acre and leave more of the land intact.”

Schroeder says a farmer can make more money of one acre of hemp than one acre of corn or soy, but the labor costs of hemp production on a large scale have yet to be determined. According to Schroeder, corn and soy market prices have been dropping and the cost of production has risen. He says you need 200 to 400 acres of corn or soy to make a profit.

“This is a trend that isn’t going to slow down,” Schroeder says. “There will be more and more farmers in the commodity sector who are going to be looking to get out. It’s more pressing than ever to find something that can be grown as a commodity, as hemp can, but also can get a higher profit without the input costs.”

Through his work with Rural Advancement Foundation International, a North Carolina nonprofit, Schroeder spent 10 years organizing individuals in poverty, including struggling tobacco farmers. When he first heard about hemp he questioned if the crop could provide the same assurance and profit margin — around $1,000 an acre — that tobacco once did. But his goal has always been to figure out ways to survive as a farmer. So why not try hemp?

“I have tried the union method,” Schroeder says. “I’ve tried the nonprofit and advocacy method. I’m not giving up on either of those, but this is a chance to try out the potential of for-profit business to establish some level of equity and justice to communities like we’re in.”

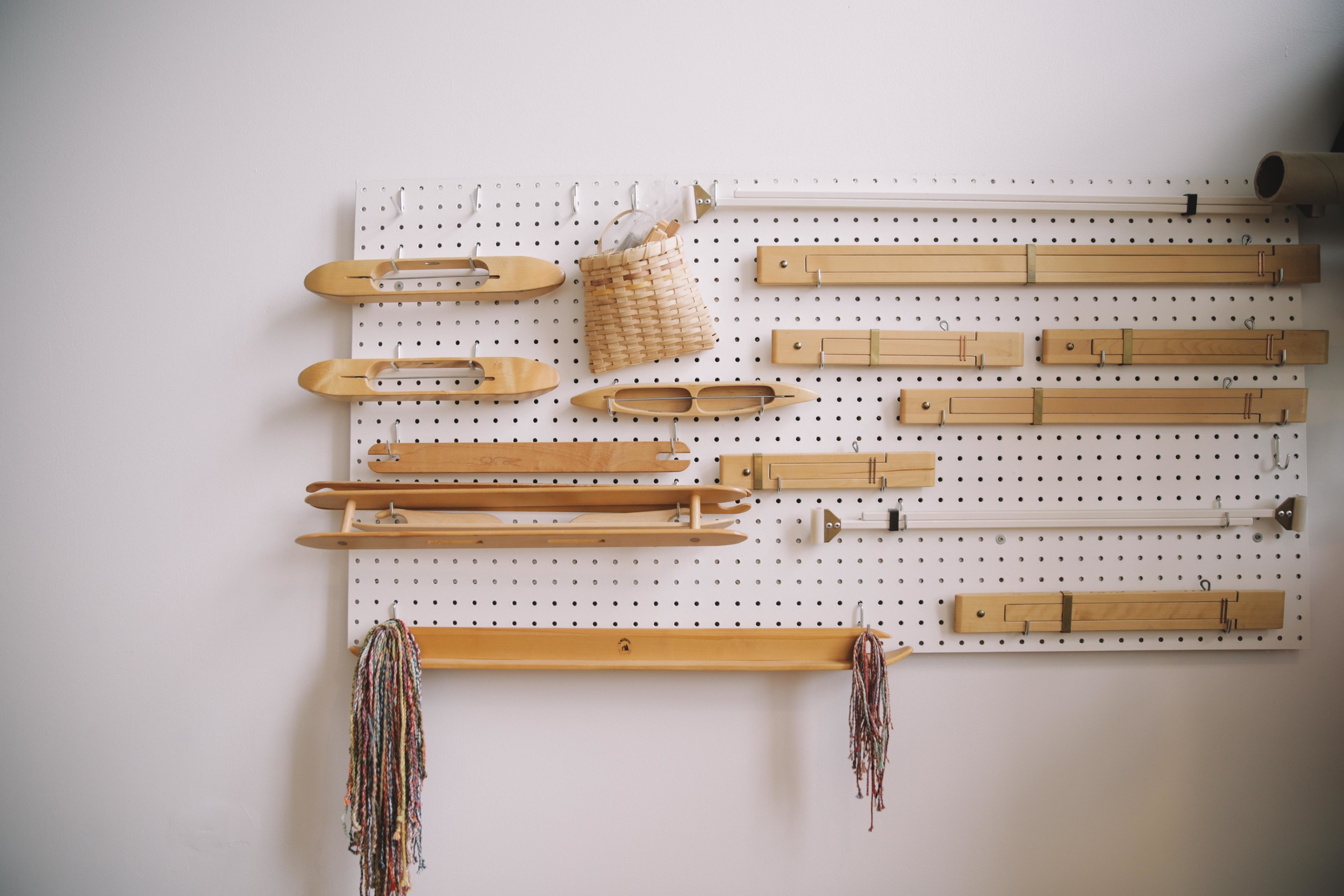

Farmers like Lewis, Schroeder and Smith are excited about the fiber markets. Fibershed is helping them market their output to buyers from small textile shops to giant companies such as Patagonia. Processed hemp fiber from Big Switch Farm and Freedom Seed & Feed’s other plots has also gone into the Kentucky Cloth Project, a cooperative effort among local producers, the Kentucky Department of Agriculture and Fibershed to blend hemp with wool and alpaca fiber, all from Kentucky farmers. The project’s goal is to “make Kentucky Cloth that can be marketed to textile and clothing designers as a unique and authentic product."

Says Smith: “There’s a lot of potential in the artisan, smaller-scale markets. There has been movement to reshore manufacturing, and I think that this is the next logical step. Not only reshore manufacturing, but to reshore the actual growing, dyeing and processing of the raw material, too.”

The people involved in the Cloth Project made sure their first output was highly symbolic: a set of 10 American flags.

~ Tenth Post Studio in Louisville, Ky. ~

The flags start with Elizabeth Smith, a spinner living in Louisville, who uses a dog comb to untangle the mangled hemp fibers. Pieces of earth flake off from the hemp fiber and float in the air around her as she works. She then begins to spin the coarse fiber into thread. The hemp went through a painstakingly long process before it made it to Smith. First it was harvested — cut at its stem — and retted. Then the stalks were jammed between fluted rollers and crushed. This process breaks the hurd, the woody core, into tiny pieces and separates it from the bast fiber. The rest of the fiber and hurd is broken apart through a process called scutching, where you basically beat the fiber bundles, over and over. The remaining long fiber, or line fiber, is then dragged through a medieval-looking comb. To put it lightly, it’s not an efficient process, and even after the process, hemp is still difficult to work with.

“When Stephanie gave me the hemp it looked like she had gone to a mountain top and stolen an eagle’s nest,” Smith says. “It’s strong and rough to the touch. I would not use this very lightly processed hemp to make a cardigan. But for the flag it’s perfect.”

The “Stephanie” she refers to is Stephanie Seal Brown, the owner of Tenth Post Studio and a weaver who creates handwoven textiles for the interior design industry. Brown is leading the textile production side of the flags for the Kentucky Cloth Project. Artisans in southeast Tennessee dyed biodynamic California cotton with indigo (blue) and madder (red). There wasn’t enough American-grown indigo, so Fibershed went to the closest source: Guatemala.

“The goal was to have everything domestic,” Brown says. “If we could have it all from Kentucky that would be fantastic, but we’re not there yet. For me, it's about, how do we bring things back stateside? Looking at what we’re capable of doing and really pushing that as far as it can go.”

Brown, who is from Oklahoma originally but moved to Louisville in 2004, is weaving together the dyed California cotton and raw Kentucky hemp that Elizabeth Smith is spinning. She is also working with seamstress Deborah Krekel, who is sewing the 500 stars. One flag has been completed and given to Farm Aid. Freedom Seed & Feed hopes also to give one to the White House.

~ Watch a Short Film on the Flag Project ~

Hemp can be more than a flag or a cardigan; it can also be your breakfast. Jacob and Carolyn Gahn, owners of Sweetgrass Granola, are producing a new hempseed granola using seed from Smith and Schroeder’s Big Switch Farm. “For The Birds” granola contains whole rolled oats, puffed rice and millet, hemp hearts and seeds, pumpkin seeds, flax seeds, Kentucky sorghum and honey and dehydrated strawberries and, more importantly, is hearty and delicious.

The Gahn Family at home in Crab Orchard

The Gahns were living in New York City — Jacob working as a computer programmer and Carolyn in theater — when they decided to move home to Kentucky and learn more about where their food comes from. They left NYC in 2009 and started working on farms around the South. Eventually they bought a small farm and home in Crab Orchard, Ky. They started making granola for themselves, and it was tasty. So they started selling it at a local farmer’s market. People loved it, so they decided to make Sweetgrass Granola legit. They hired two employees who make granola once a week in a small commercial kitchen in the Gahns’ home. They produce 150 12-ounce bags of granola a week. The product is in stores across Kentucky, including Whole Foods, selling at $7 per bag.

Hempseeds can also produce food products such as oil, butter, tofu, non-dairy beverages, ice cream, protein powders, cereals, crackers and bread. Three tablespoons of hempseed contains 11 grams of protein, 7.5 grams of Omega-6 and three grams of Omega-3.

"Hemp has a lot of advantages over flaxseed,” says Jacob. “The ratio of omega fatty acids in hemp is more appropriate for human digestion. It's also a complete protein in the same way that quinoa is.”

Hemp has been around for long time; so have many of the folks involved with bringing it back. But there’s also some young blood in the game. Alyssa Erickson and Kirsten Bohnert have taken an interest in hemp — and an interest in stopping the brain drain from their their home state.

“It’s important that our generation and the ones behind us see a future,” Erickson says. “And no one sees it with tobacco. No one sees it with coal. That’s not what our generation sees. I think hemp is something that everyone can look forward to. I’d like to build this industry and find opportunity for people our age, because we’re losing them.”

Alyssa Erickson and Kirsten Bohnert, the Kentucky Hempsters

Erickson and Bohnert call themselves the “Kentucky Hempsters.” They use Facebook and Instagram to share daily and weekly updates and information. They’re young, they’re attractive, and they’re women, so they stand out among the usual Kentucky farmers. They see their role as the communication bridge between farmers, manufacturers, processors, educators and activists, to help promote their work and connect them with those who can help them. They have dreams of doing school tours of hemp fields, among other adventures.

“We want to take advantage of our youth and use it for something positive,” Bohnert added. “When you say Kentucky to people if they think one thing it might be hillbilly, it might be tobacco, but we’d love for people to think about hemp when they think about Kentucky.”

In the rolling fields of central Kentucky, the hemp is growing high and tall. At the University of Kentucky research farm, the hemp stands over 10 feet tall, high above the Kentucky Hempsters’ heads. Inside the greenhouses nearby, hemp plants of all sizes are packed in side by side. Because hemp and marijuana look so much alike, the greenhouse scene feels and looks illegal, but none of it is. The research is led by David Williams, UK professor of Plant and Soil Sciences, and Rich Mundell, research production specialist with the Kentucky Tobacco Research and Development Center at UK, which researches new uses for tobacco, including the plant-made pharmaceuticals sector.

“It’s like finding a new species in a way,” Williams says. “Almost never, in agronomy, does that kind of opportunity present itself. It’s very exciting to be working with a plant that none of my peers are working with.”

Williams and Mundell planted seeds that were donated by individuals. The resulting plants are tested to see if they qualify as “industrial hemp,” meaning they contain no more than 0.3 percent THC. To test THC content, they use male plants to fertilize the buds of female plants and leave them in an isolation chamber for three days. Then the plants are transferred into the greenhouse where they will mature. If that seed is under 0.3 percent they will save it and catalog it for future use in a breeding program.

They are also in the early stages of manipulating the growth rate of the plant, attempting to keep the plant shorter without affecting yield for easier cultivation. UK has three fields dedicated for hemp research: one for a fiber crop, another for oil seed, and the third was hand transplanted with seedlings of a cannabinoid-rich variety of hemp, grown for its medicinal qualities. Their focus is on research and science, but Williams also thinks about the economic side and questions how big of an impact hemp may have.

~ Researchers at UK Study Hemp ~

“I personally wonder if we all understand how corporate America operates,” Williams says. “If the fiber produced from hemp is not far superior to current technologies or if it’s not as good, but much cheaper than current technologies, I don’t know what will happen. There will be a hemp food market in the United States, but what will the scale be? Only the consumers will determine that. For all the things that cannabis can do, the cannabinoids potentially hold a very very high potential for profitability.”

Williams isn’t the only one who believed in cannabinoids, or CBD oil. The biopharmaceuticals business is profitable all around the world. Near Lexington, Jake and Andy Graves are deep in that industry.

When we pulled up to the field, the strong fragrance of cannabis filled the air. Andy Graves, CEO of Atalo Holdings Inc., a hemp company based in Winchester, Ky., proudly showed off 27 acres of cannabinoid-rich hemp plants — each planted five feet apart, in 1,700-feet rows, with 2,300 plants per acre. They were hand transplanted over the course of one month from clippings of mother plants. It was a very labor-intensive process, but the end product is pristine and beautiful. Andy is proud of it; his smile shows that.

Andy is a seventh-generation hemp farmer and 12th-generation Graves in America. His 89-year-old father, Jake, started working in the hemp fields of Kentucky when he was 16 years old. And after 20 years of advocating for the legalization of hemp, the Graves are finally replanting the seeds for a new economy.

The Graves family started farming in Kentucky in 1800. In 1910, Jacob Hughes Graves II’s hemp was considered “the best in the world.” Graves and Philip Glass gathered hemp seed from all over central Kentucky. But in 1942 the seed was confiscated by federal marshals when hemp was made illegal. In 1944, the Graves’ seed was then redistributed throughout the country, sent through the mail in small packages. Farmers and non-farmers alike were told to grow it for the war effort.

“The seed that was confiscated from dad’s father was then in turn passed back out. Their charge was to grow ‘Hemp For Victory,’” Andy says.

But now, the cycle is coming back around for the Graves family.

Atalo holdings ceo Andy Graves

“Society goes through evolutions and revolutions,” Jake says. “And this is a plant that is evolving from fiber to pharmacy. China has used it for medicine for tens of thousands of years.”

He’s referring to CBD oil. Mothers of sick children, suffering with everything from cancer to epilepsy, have flooded into Colorado to get access to CBD oil since cannabis was legalized, coining themselves “Marijuana Refugees.” Besides relieving pain, one of the 64 known cannabinoids in the hemp plant, CBG, has been associated with reducing appetite. Reducing the appetites of central Appalachians is of interest, with high adult obesity rates of 33.2 percent in Kentucky, and 35.1 percent in West Virginia, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“If you have tremors, it (CBD oil) tells the body to relax and quit tremoring,” Andy says. “For these children that have epilepsy, they relax and stop seizuring. The idea that my father and I would be growing something on our farm that helps people that way, and the last crop that we grew — that had economic value — was a tobacco crop, and every day we knew that we were growing something that was thought to be harmful to people. The reversal of that is extraordinary for us to think about.”

Perhaps, for the Graves family and so many others like them, that's the hope hemp is offering: a rebirth, a second chance to turn away from the usual regional industries that have been looked at by outsiders as harmful and destructive. A green revolution in a region of darkness.

Atalo Holdings' Jake Graves, Andy's Father

The Graves are part of Atalo Holdings, Inc, a Kentucky corporation specializing in research, development and commercialization of industrial hemp. Atalo imported and distributed of approximately 14,000 pounds of hemp seed to its 30 growers, who will raise up to 545 acres of the crop across central Kentucky. Future purchasers of their products include Dr. Bronner’s, which will use hemp oil in soaps, and Nutiva for hempseed.

In the 1990s, Andy and Jake spent much of their time educating folks across the nation about hemp, using radio, television and all forms of media to spread the word. Their efforts led to the passage of a research bill in Kentucky, which established a hemp commission.

“We’re trying to give back to this community that we have been a part of forever and ever. Maybe in his lifetime he can look back and say, ‘Maybe I did something worthwhile,’” Andy says, referring to his elderly father.

The Graves are building an industry slowly but surely. They know the market is there. They just need to develop the supply chain and get the growers motivated. They plan to start a seed bank, like their ancestors, and learn how they can keep farmers — young and old — farming. Both Andy and Jake say the industry has arrived and the only thing left to do, the only thing they've ever been able to do, is wait for others to catch up.

“If I was at the ocean and I turned my back to the ocean, would I think that the tide wasn’t going to rise? No,” Andy says. “It’s like that. Farmers and people in the business community need to see this is here. It’s very evident that this is going to be an impact. I can’t guess what CBD is going to mean to the public, but I think it’s going to be big. I think the oil as a fine food source is going to be huge.”

Despite the efforts of the hemp entrepreneurs, what remains to be seen is if the market for the plant will be as robust and sure-minded as the plant itself. Will the DEA reverse its stance on the illegality of hemp once the five-year window authorized by the farm bill is up? Can small-scale farmers truly support themselves and enhance their local economy by growing hemp?

Despite these questions and doubts, for Joe, Lora, Andy, Todd, Mike and many other Kentuckians, hemp is a chance to reclaim their land, to put the very dirt under their feet to use not only for themselves, but also for their children and generations to come. The people involved with Kentucky hemp have realized that the future of their region depends on them. They understand that dependance on mono-economies, dictated by fluctuations of supply and demand in volatile global industries, can bring not just years of riches, but later years of poverty. They know that every day will be an experiment, but they hope that it's a learning experience that will forever change the food we eat, the clothing on our backs, the materials we use to build our houses and the medicines we rely on.