The Opposite of Bullshit

How an Atlanta Rapper’s “Ghetto Gospel” Is Changing His Community

In the concrete jungle, you prey or a hunter.

When you kill a nigga, they say his soul haunts ya.

I’d rather sleep with a ghost than sleep with the fish,

Be judged by 12, than carried by six.

Scary lyric, isn’t it? Conjures intensely frightening images. Here’s another for you:

So you’ll gladly put your money in this sack.

Yes, sir, this thing is loaded,

And I have the hammer back.

If I were you, that’s what I'd do.

Let’s consider why these lines scare us. You already know, from our headline and the photograph, that you’re reading a story about a black man, specifically a rapper named Killer Mike. You already imagine both these lyrics coming from the mouth of a black man. When you think of that pistol in your face, its hammer pulled back, what do you picture?

Neighborhoods where you should not go? Or maybe that time you saw the young black man on the corner when you were stopped at a red light and you quietly hit the power door locks, just in case?

But allow me to present you with a new piece of information. Killer Mike wrote only one of those lyrics. The second one comes from a song by a white Kentucky songwriter named Chris Knight. When “If I Were You” was released in 2001, critics praised it as a touching portrait of the desperation that comes with homelessness. So when we hear its lyrics, sung in Knight’s Kentucky twang over gentle finger-picked guitar, we assume Knight is inhabiting a character.

We believe automatically that Chris Knight is not — could never actually be — that homeless man with a gun.

Put the same lyric in Killer Mike’s mouth, though, and you think something different, don’t you? You do not assume instantly that Mike is merely inhabiting a character. No, in your mind, he is the man with the gun in his hand.

Think for a second about the history of Southern music. Our Appalachian musical heritage has a long and grand tradition of what the academics call “murder ballads” and what the musicians just call “killin’ songs.” The archetype, perhaps, is “Knoxville Girl,” in which the protagonist beats a girl with a stick “until the ground around her within her blood did flow,” then drags her by her hair into the river to drown.

Southerners have written and still sing hundreds of ballads about killings. We sing them at festivals and around campfires. Academic musicologists study them as cultural artifacts. Though they are dark indeed, no one finds them too objectionable. Johnny Cash “shot a man in Reno just to watch him die,” and we’re not scared. We just love Johnny more.

But when the gun in the song is in the hand of a black man, things get weird. The song becomes less cultural artifact and more an object of fear. We reflexively object. We worry about what the children will hear.

You think we have a little double-standard problem here? Yeah, me too.

The second time I met Killer Mike, I went to visit him at the barbershop he owns in Southwest Atlanta. We sat in the back room, and I walked him through my little lyric comparison. I told him about the double-standard problem I saw and how it disturbed me. I asked him what he thought about this.

“It bothers me, too,” he said. “I feel sorry for my neighbors who may be a little afraid of me, because you deny yourself such a valuable experience when you shut yourself out from other human beings.”

This is a lesson Killer Mike has taught himself over the years.

“I mean, being a young black man in the South can be a difficult and arduous task at times, but at some point, after you get past the anger and some of the confusion of adolescence and you grow up and travel the world, the people who are stereotypically supposed to hate me, or the people I’m supposed to mistrust, have always been my neighbors. And for most of my life, we’ve been really nice to each other.

“That’s my honest experience with whites in the South, and I think a lot of times when people say ‘Southerner’ or make those crass jokes, I, as the black guy, am supposed to excuse myself from the joke.

“But we’re all Southerners. We all talk with these drawls and twangs. We all go to the race track on Sunday. We all go fishing. I don’t have a Dixie flag on the back of my pickup, but it still has mud flaps and big tires. So you’re talking about me, too. I am that redneck guy you’re talking about. I’m not him, racially. He’s not me, racially. But culturally, in the geography of where we’re from, our grandfathers did the same things. They did the same shit. I fiercely identify with being a Southerner because I value that culture. Everybody else thinks we’re country as shit, anyway. So why not just be who I am? I am Southern. I rap. I wear cheesy jewelry. I bounce around on stage. But when I take that shit off and go home, I fish. And I’m your neighbor. I do the same things you do.”

He concludes, “I’ve done better not running away from that than trying to.”

This is the story of Michael Render, father of four, husband, entrepreneur, proud Southerner, genius rapper — and a man who makes it his business, every day, not to shut himself off from other human beings.

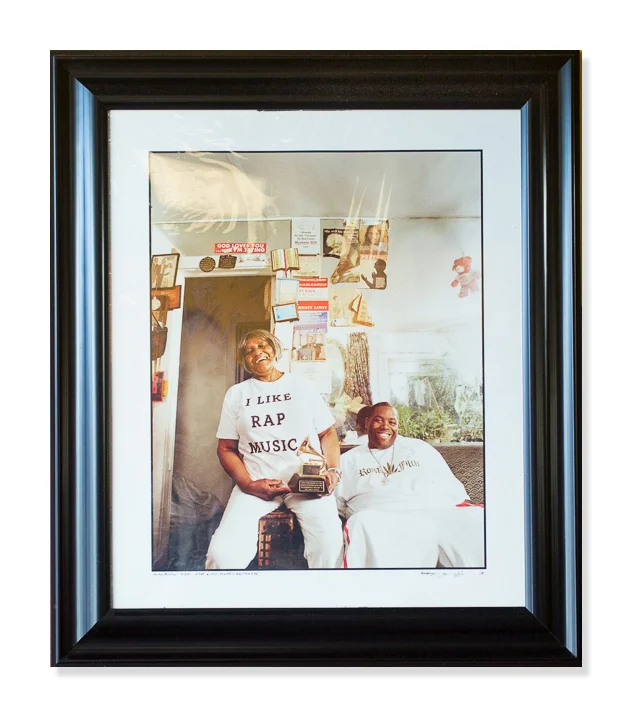

Killer Mike in his barbershop, at left, and, at right, at home with with his daughters, Michael, 7, and Aniyah, 16

Killer Mike made his first waves in the hip-hop world when he appeared on “Stankonia,” the quadruple-platinum 2000 album by the gods of the ATL hip-hop scene, Outkast. He swapped verses with Antwan Patton, aka Big Boi, on “Snappin’ & Trappin'.” A year later, he won a Grammy for Best Rap Performance by a Duo or Group for his verse on Outkast’s “The Whole World.” In 2003, when he was 28, he got a major-label deal with Sony and released his first solo album, “Monster,” which peaked at No. 10 on the Billboard album-sales chart.

Although I knew for a long time that there was a rapper from Atlanta named Killer Mike, I had never paid attention to his music, even after I discovered that Mike and I had a mutual friend. I can’t say I became a fan until 2012.

That year, I picked up a new buzz among the music critics when Killer Mike released his album “R.A.P. Music.” The Chicago Tribune music critic Greg Kot, whose tastes I’ve long respected, wrote that the record “intertwines the personal and political tragedies of the last three decades in the African-American community.” Kot concluded that Killer Mike had “added a must-hear chapter to the hip-hop bible.”

So I listened. Over perfectly calibrated beats by a white Brooklyn rapper and DJ named El-P, I heard lyrics that had the kind of consciousness and wisdom I hadn’t heard from hip-hop since Public Enemy, 20 years before.

We brag on having bread, but none of us are bakers.

We all talk having greens, but none of us own acres

.

If none of us own acres, and none of us grow wheat

,

Then who will feed our people when our people need to eat?

So it seems our people starve from lack of understanding

,

’cause all we seem to give them is some balling and some dancing

And some talking about our car and imaginary mansions.

We should be indicted for the bullshit we inciting

.

Hand the children death and pretend that it's exciting.

— Killer Mike, "Reagan"

Well, now. What to make of this? An Outkast protege who had ridden the wave of success that had folks declaring Atlanta the hip-hop capital of the world, and here he was, looking squarely back at members of his own community and challenging them to apply the fruits of their fame to things that matter more than balling, cars and cribs. He was challenging them to reinvest in their community, to serve as role models who were more than, as his lyric continued, “advertisements for agony and pain.”

I found myself wanting to meet this man, to talk to him, to try and find out what he was made of.

Remember that mutual friend I mentioned earlier? I called her.

Killer Mike’s schedule is tough. He tours incessantly. Try to set up an appointment for a call or meeting with Mike and you’ll get a few emails like this: “I am in Idaho today, and I am on flights tomorrow, but when I settle in San Antonio, we are good to talk.”

Our mutual friend, Susanne Pesterfield, began trying to set up a lunch date last summer before we launched The Bitter Southerner but was still trying to nail it down in early August when we actually launched. On the day we launched, Susanne sent Mike a message and told him about The Bitter Southerner. She thought he might like the idea, she told me.

The next day, Susanne called me. It seems Mike had read our opening essay and said something to her along the lines of, “The Bitter Southerner? Hell, yeah!” And he offered to put our crew on the guest list for a show he had coming up with El-P, that very night, at the Masquerade on North Avenue in Atlanta.

I called Dave Whitling, and we met Susanne for the show.

I’ve seen hundreds, maybe even thousands, of rock shows. Hundreds of country shows, too. Sadly, I can count the number of hip-hop shows I’ve attended on two hands. I can say, however, that one of them changed my life forever. It was in 1991, when I went with my friend David Barbe, who now directs the Music Business Certificate Program in the University of Georgia’s Terry College of Business, to the old Omni in downtown Atlanta to see Public Enemy.

Public Enemy were the first hip-hop act that combined the revolutionary sonic force of hip-hop with the lyrical insistence, anger and bluntness of the punk rock David and I loved as college students in Athens. As I recall it, we were the only two white people there.

I remember feeling electrified, because I was in a place where I was supposed to be scared and I wasn’t. In one way, it was a night like many others I’d had, when the power of the right music and the right crowd produced a feeling of deep commonality. But this night had something extra. We had ours, and hip-hop was theirs, but Dave and I never once felt like intruders. We were willing to listen, so we were welcomed. Ever after, I found that I would call bullshit on myself every time I thought about what was ours and what was theirs.

On that night in 1991, Michael Render was a 16-year-old being raised by his grandmother in Adamsville, a neighborhood on Atlanta’s west side where the poverty rate still consistently hovers in the mid-40 percent range. The plague known as crack cocaine was falling hard on downtrodden communities all over America, and Adamsville was no exception. Mike’s grandmother made sure he spent most of every Sunday in a tiny Pentecostal church called the Bethlehem Healing Temple, whose pastor was a woman named Mother Mary Jackson.

But when he wasn’t in the church, Mike was listening to Public Enemy, too.

Seeing Killer Mike perform live for the first time, 22 years later, was a very different experience. It was, in fact, the best hip-hop show I’d ever seen. Why? Two reasons.

The first was the crowd itself. I’ve never attended a single concert — of any kind of music, anywhere — with such a thoroughly mixed audience. If it takes all kinds, then we had what it took that night. There was one of everybody, every color, every possible permutation of the multiracial South.

The second reason was that I had never seen a hip-hop artist engage with a crowd so directly as Killer Mike. Mid-set, El-P brought in the skittering beats that mark the beginning of “R.A.P. Music,” and Mike introduced the song as he always does, with these quietly spoken words:

“I've never really had a religious experience in a religious place,” he said. “Closest I've ever come to seeing or feeling God is listening to rap music. Rap music is my religion. Amen.”

Then his deft, eloquent rhymes began to flow fast.

What I say might save a life.

What I speak might save the street.

I ain't got no instruments,

But I got my hands and feet.

Hands gonna clap and feet gonna tap.

El-P beats to make that snap.

And I ride them with my raps,

And they all tight as my naps.

And my naps is all I got

And this beautiful ebony skin.

And the music in my heart

And the words put in the wind.

And the words put in the wind

Coming back like a boomerang.

When I take this microphone, point it at the crowd, they start to sing:

He pointed his microphone at the crowd, and sure enough, they sang:

This is jazz, this is funk, this is soul, this is gospel,

This is sanctified sex, this is player pentecostal.

This is church: front pew, amen, pulpit.

It’s what my people need

And the opposite of bullshit

— Killer Mike, R.A.P. Music

All those faces, colored in all the hues of Killer Mike’s hometown, they bounced up and down in unison, singing the chorus for all they were worth.

I realized I was witnessing a truly and thoroughly modern expression of Southern culture. It spoke to the urgency of the social problems we face, but it did so with tremendous optimism. It celebrated our musical roots and our gleeful propensity to mix the sacred with the profane. And leading it all was this giant smiling man named Killer, unafraid to rhyme about his beautiful ebony skin and the words he puts in the wind, giving our people what they needed: the opposite of bullshit.

If there was a Church of Rap, motherfucker would be bishop.

That Killer Mike can pull this off, night after night, all over the world, is at least in part a product of his raising in Adamsville with his grandparents, Bettie Clonts and Willie Burke Sherwood, after whom Mike named one song on the “R.A.P. Music” album.

His grandparents were members of Mt. Olive Baptist Church on Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, just outside of Adamsville. But the Baptists were a little too uptight for Mrs. Clonts.

“Even though we belonged to the Baptist church, my grandmother preferred these small Pentecostal and Holiness churches,” Mike says. “We were a two-churcher family. We’d do early morning service at our home church, then Sunday School, then we’d go to these other churches and be there the rest of the day.”

Most of those afternoons were spent at Bethlehem Healing Temple, where Mother Mary Jackson usually invited musicians from other churches to play with what Mike calls “the little ad hoc choir” at Bethlehem.

“It was all-out funky, dope music,” he says. “We had great singers. There was more wailing, too, because a lot of the older hymns were still there. It was like what you would have gotten out of the fields, where you just sang to get through the day. There were a lot of testimonials.

“I learned my Bible there. It was an interesting place. The music was different there. The focus was very different there. The focus was on children and the poor and helping people.”

But Mike never, as the saying goes, “got religion” at Bethlehem.

“I don’t know if I left religion,” Mike says. “I don’t know if I was ever in it as more than a curious observer. You know, there’s a Langston Hughes short story where he talks about them going to church and sitting on that front pew …”

The story is called “Salvation.” It’s from “The Big Sea,” Hughes’ autobiography. In it, the 12-year-old Hughes is taken by his aunt to a revival meeting. The minister makes an altar call specifically aimed at the young, saying, "Won't you come? Won't you come to Jesus? Young lambs, won't you come?"

After a while, all the young people in the church have come forward except for Hughes and a young man named Westley, who quickly joins the other young people after he whispers to Hughes, “God damn! I'm tired o' sitting here. Let's get up and be saved." Ultimately, Hughes himself relents. “I decided that maybe to save further trouble, I'd better lie, too, and say that Jesus had come, and get up and be saved.”

The story ends this way: “That night, for the first time in my life but one for I was a big boy twelve years old — I cried. I cried, in bed alone, and couldn't stop. I buried my head under the quilts, but my aunt heard me. She woke up and told my uncle I was crying because the Holy Ghost had come into my life, and because I had seen Jesus. But I was really crying because I couldn't bear to tell her that I had lied, that I had deceived everybody in the church, that I hadn't seen Jesus, and that now I didn't believe there was a Jesus anymore, since he didn't come to help me.”

“I was that kid,” Mike says. “I knew that whatever everybody was feeling, I didn’t feel. That didn’t mean that I didn’t believe that God existed, and I knew the moral good I was learning. There was some real fire and brimstone stuff in the Pentecostal church, but there was some moral good that I was hearing in the gospels, which I recognized as something valuable. But I just obviously didn’t have the same feeling that some people had, whatever it was. So I never adhered in the same way.

“I support the beauty of religion, the moral beauty, the stories you read. It’s amazing. But the fact that we have these three big religions that know they’re related and they can’t get their shit together is pretty disheartening. So how could I buy in to any of the three? I do think we’re here for a purpose. And even if we’re not, there’s nothing wrong with us having created a god for ourselves. But we should honor that creation better.”

What did stick with him at Bethlehem was the value of the people around him, who faithfully did the simple work of honoring the creation.

Killer Mike with his grandmother, the late Mrs. Bettie Clonts, holding his Grammy Award. This photo hangs on the wall of his barbershop.

I ask him about a lyric from his song “God in the Building,” which pays very specific tribute to the women he grew up among in Adamsville.

“I love those old ladies because …,” he begins and then pauses. He's wiping away a tear. He takes a second to recover, and then quietly, in a choked whisper, starts again. “These women, they worked as domestic servants, they dealt with philandering men, they raised ungrateful children. But they came to that church every single week. Whatever love they had to give that wasn’t received in the world, they just brought to the church and gave it to whoever needed it.”

I likely will never know these women who inspired him, but even though their religion never fully took hold with young Michael Render, it is clear they saw something very special in him, too.

The church ladies weep when they hear ya man speak.

They say they see God in me, but I'm in the streets.

They ask me why I'm rappin', tell me I'm called to preach.

I smile, I kiss' em on they honey brown cheeks.

I tell' em God bless'em and they can serve for me,

But you can never walk on water if you still fear the sea.

If Jesus came back, Mother, where you think he'd be?

Probably in these streets with me…

— Killer Mike, God In the Building

“It’s with tons of respect that I say, ‘God bless you and you can serve for me,’” Mike says. “But they are afraid of the world. And the world is fucked up. But they don’t understand that Jesus was never in the church; he was in the world.

“Kids like me, who they raised to have empathy and sympathy and love for the basic goodness for all humans, we’re supposed to be in the world. We’re supposed to be in the streets. We’re supposed to be a walking morality for other human beings. We are supposed to be good to people. You’re supposed to be.

“I want to leave this a better place when I go,” he says. “That’s what this is all about. I want to leave four capable human beings. I want to leave a legacy with a woman that other people can emulate.”

His family life certainly appears solid. I have never, in all my years of concert-going, seen a performer bring his entire family on stage with him during a hometown concert, as Mike did the night I first saw him perform. But there he was with his wife of seven years, Shana, and all four of his children: Malik, 19, Aniyah, 16, Pony Boy, 12, and his baby daughter, Michael, who just turned 7.

If “justice in the music business” was not an oxymoron, a man who writes and thinks like Killer would be a bigger star.

“I think he could be,” says Charles Aaron, a North Carolina writer who covered music for decades at the helm of Spin magazine and Spin.com (and, full disclosure, a longtime friend and former roommate of mine). “I think it’s just purely a case of production choices. If he chose to work with any of a handful of producers — there are at least a dozen people probably within 15 minutes of his house…”

But Aaron acknowledges that Mike and El-P don’t make tracks that sound like whatever’s current on the radio. “That’s definitely not what Mike is leaning toward,” he says. “He’s leaning toward a harder sound at a certain tempo that really reflects the ’90s East Coast even more than it reflects Outkast and the other Atlanta stuff. He’s definitely trying to be hard. Mike shouts so that you will hear everything he’s saying and be blown back by it. When you’re being aggressive with a message that serious, it can be tough.”

Aaron sees Killer Mike’s long-term impact in the effect he has on live audiences. “He tours all the time,” Aaron says. “He can do every kind of crowd: indoor, outdoor, wherever. And when you’re as good as him, you’re going to impact people in a strong way. And it’s not going to be like, ‘Wow, I remember when he did that song.’ It’s going to be like, ‘I remember Killer Mike.’

“There is such an abundance of talent and artistry in the Atlanta hip-hop world,” Aaron continues. “There are so many different personalities who make up the city. Killer Mike plays a really important role in that constellation of characters who are shaping kids in various ways. These artists are just really impactful, and there are just a ton of them in Atlanta. It helps sustain Mike that he’s part of that.

“But it takes a lot of fortitude to just follow your path.”

Mike says this about his place in the firmament of rap stars: “I’ve had a lot of rappers who are more successful say to me, ‘Aw, man, you shouldn’t even be rappin’, you should just be preachin’.”

I tell him I think he preaches through his music.

“Yeah, but people think it’s supposed to be on some bigger plateau,” he says. “I just know it reaches the people it’s supposed to reach. That’s what I know. That’s what I would say to those old ladies or people who say, ‘Mike, you’re underrated or overlooked.' I don’t have time for that. I honestly feel like my mission is to say something while I’m here. To say something that’s brave, something that’s courageous and that’s real and that’s needed, because I’m gonna die someday.”

The knowledge that he would die someday came easy in Adamsville. The teenage Michael Render saw firsthand the death rain that cocaine inflicted on his own community in the late 1980s and early ’90s.

“Black people had never had access to that type of drugs or that type of money,” he says. “I saw the world, from a child’s perspective, going batshit crazy. This is not normal! My grandparents were raising me, so our life was pretty normal. We didn’t have cable. But at my Mommy’s house, there’s fucking cable and fucking cell phones and fucking cars and shit.”

By the early 1990s, the crack epidemic had hit Atlanta’s poor neighborhoods so hard that the national press began calling the city one of the nation’s most dangerous. Mike took solace in music and books.

“We had high-art, avant garde rappers like Public Enemy,” he says. “That was a monumental time.” The records of NWA and Public Enemy, he says, were “the first music I heard that validated for me that what I saw happening on Simpson Road, that what I saw happening on Martin Luther King and around, was for real. The music gave me a place to take solace, to know I’m not crazy, that I’m not trippin’.”

It was also a fairly monumental time in the Atlanta public school system. The late Dr. Asa Hilliard III, the Fuller E. Callaway Professor of Urban Education at Georgia State University, became a consultant to the Atlanta school system. Hilliard believed that young African-Americans should learn more about historical achievements among blacks — and about the roots in ancient black Egypt of certain philosophical, mathematical and scientific theories that had shaped civilization.

Hilliard’s theories drew fire from certain quarters of academia, but as he told The Washington Post in 1989, he simply hoped to create balance in historical instruction. "We mis-teach European history, as we mis-teach American history," he told the Post. "Basically, what we should be teaching is the whole story, the truth. That's the bottom line."

“It was the damnedest thing,” Mike says. “It helped black kids understand their place in world history. This is Egypt. This is East Africa. This is West Africa. Not just a strictly pan-Africanist, ‘us-vs.-them’ view, but ‘you are a part of world history.’ It was just new awareness for me.”

The new knowledge led Mike to explore other religions, but ultimately those explorations led him to the same conclusion. “I realized that every one of them just kind of ends up with a guy in a dress and a funny hat,” he says.

What Mike preaches today is something entirely different. You can just call it what he calls it: ghetto gospel.

Let’s make something clear. Killer Mike’s songs do indeed have guns and shootings in them. They are often profane and graphic in their descriptions of sex and violence.

His songs can make the fainthearted flinch, but as Mike himself puts it, “That stuff’s the truth, too.”

I pray the Lawd hear me, but really Lawd, is ya listenin’?

Praying when I'm in trouble, I'm speaking with forked tongue.

I say I'm out the game, but I'm flinching like George Jung.

I must be in the clutches of Satan, it's all warm.

My mama took me to the "root lady" to read my palm.

She put beads on my neck saying they protecting me from harm.

But fuck this old witch, I went and got a gun.

Oh Lord, Jesus, glory ...

— Killer Mike, Ghetto Gospel

Here’s the way I figure it. If Killer can give us hillbillies our killin’ songs, we can give him his. In the modern age, his are more relevant than ours, anyway. But more importantly, as he and his music have matured, Killer Mike’s stark portrayals of street life are more often used as context for a larger narrative: a story about what must be done to redeem neighborhoods like Adamsville. Killer Mike’s ghetto gospel is about self-sufficiency.

“To me, what ‘Ghetto Gospel’ means is providing guys my age in their 30s — and younger guys — with the spiritual optimism through music to become leaders of their community, to do something different, to own something, to revitalize, to wake up those bones,” he says. “My people aren’t hopeless. Poor people aren’t hopeless, period. But they gotta decide to not be poor anymore. I’m a street preacher. I rant. We don’t need everything they give us. We shouldn’t even want it. We should want more for ourselves. We should want more for our environment.”

Last year, Killer Mike made his legend even larger when he appeared on the podcast of then-Fox Sports commentator Jason Whitlock and got into a vehement argument about a simple question: Should rappers and athletes who hit it big reinvest part of what they earn in the communities where they grew up? Whitlock argued that it was quite enough for the rappers and athletes to generate economic activity by selling tickets to games or concerts and by earning endorsements from corporate sponsors.

Killer Mike basically told Whitlock he was ignorant.

“Jason Whitlock says that athletes should be ‘acting better,’ which is code word for acting in a more appealing way to whites, to get more money, because somehow that advances the community as a whole,” Mike says. “Every community has icons that little boys and girls dream of. That pushes them individually and then the community as a whole, and they attach themselves to that. The Polish community. The Russian community. The Jewish community. Southern white communities. Black communities. Every community has that — those heroes. But I’m like, if we have these heroes, I see it as more important for them to reinvest in the communities they come from. If they grew up walking by a McDonald’s to and from school, I would rather see them own that McDonald’s now that they have the means to do it, because they can employ 25 children from that community.

“I’m talking to my community,” he says. “I’m talking to the men in particular in my community. I’m talking about men of means in my community. And even more specifically, I’m talking about rappers. And if you want to know which ones I’m talking about, pick up a rap magazine and start flipping pages.”

For the only time in our conversation, he cites one of his own lyrics without my prompting: “The ballot or the bullet, some freedom or some bullshit/Will we ever do it big or just keep settling for li’l shit?”

“You know, we’re not free,” he says. “You’re not free if you don’t own your own community. You have no freedom; you just occupy a space. That is not the same thing as freedom. And when I say ‘we,’ I first mean the African-American community simply because I am African-American, and this community is a more depressed community, with double the national unemployment rate.”

He starts citing statistics, such as the fact that more than 20 percent of the African-American working population over 16 years old are employees of the federal, state or local governments — and the fact that a much smaller percentage of African-Americans (3.6 percent) is self-employed, compared to a national average of 6.2 percent.

“I do not celebrate that type of employment, because at any time the government chooses to shut down, our community is shut down,” he says. “We don’t own or run finance or commerce in our own community.” He talks about role models like George A. Andrews, who founded Capitol City Bank & Trust Co. a chain of banks that serve largely African-American communities in Atlanta and across Georgia.

“Last week, I went and opened up a bank account at Capitol City Bank and I challenged people on Twitter to do the same, because we need to support business directly in our own community,” he says. A tweet from Killer Mike is no small thing. As of this writing, he has 84,000 followers @killermikegto.

He talks about the half-century-long sharp decline in African-American ownership of farmland. According to the latest data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s quinquennial Census of Agriculture, African-Americans constitute a little more than 1 percent of all American farm operators. The average black-operated farm is 104 acres, while the average among all farms is 418.

“All of this bullshit ego and all of this extra, embossed lifestyle we lead as rappers and athletes … if we’re not in control of something as basic as food in our community, if we’re not in control of that, we are nothing,” Mike says. “We are lost. We are lying to children.”

He continues: “I want to tell people the truth about how to change it. It can change. It can not be what it is, because It hasn’t always been that. Auburn Avenue has not always been a vacant shell, Simpson Road has not always been a wasteland, Joseph Lowery Boulevard has not always been famished by the absence of black businesses. You should have a business in this community where you can hire people. You should own something in the community.

“That’s all I’m telling my brothers,” he says. “Everything we think we have? We have nothing. We’ve gained nothing but the ability to buy shit. And you being a customer is nothing. They’re growing customers. Customers are born. Customers die. You’re just a statistic. But we could own the communities we’re in. We could own it. You could own four Citgos. You could own a Chevron. You could own a grocery store. You could own it. We could do this differently. But we’re not.”

All of which brings us back to a barbershop at 3614 Roosevelt Highway in Southwest Atlanta. If ghetto gospel is Killer Mike’s message, then Grafitti’s SWAG Shop is what the church ladies would call his “living testimony.” The SWAG stands for “Shaves, Washes and Grooming.”

The first time Susanne managed to get us together with Mike and his wife Shana, over fried chicken at Mary Mac’s Tea Room (what else would you feed the bishop?), Mike talked about the importance of the barbershop in black business communities.

He laughed and told us, “You white people don’t understand this, but we have to go to the barbershop every two weeks, without fail.”

Mike had seen mothers becoming afraid to take their children to local shops because of drug-dealer activity nearby. So he and Shana decided they would put their beliefs into action by opening the SWAG Shop, a safe and welcoming place for his community and its children.

My Uncle Clifford owned the barbershop where I grew up. I like Uncle Killer’s place better. All I ever got after a haircut was a stick of Fruit Stripe gum. At the SWAG Shop, every little boy who comes in for a trim gets a Hot Wheels car. How sweet is that?

The place is painted with colorful murals. The entire right wall of the front part of the shop is covered with a mural of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., obviously in mid-sermon. Hung near it is a painting of Killer Mike, obviously in mid-rap.

Closing time is nearing as we talk, and as we’re about to wrap things up, Mike’s son Malik knocks on the door. Malik had greeted me when I’d arrived earlier in the afternoon. I introduced myself and said I was there to meet Mike. Malik had smiled and said, “That’s my dad.” He had broom duty in the shop that Sunday, and he wanted to tell his dad goodbye. Mike got up, hugged his son and told him he loved him. Malik responded in kind, covered a few details about tomorrow’s schedule with his dad, and headed out.

Mike eased back into his chair. “This place employs people,” he says. “And we serve at least three or four hundred people. This is one of many I plan on doing. This is a shared experience — me learning how to become a businessman and me providing a service for the community.”

In mid-March, Mike announced proudly on his Facebook page that the Georgia State Board of Barbers inspector had given the SWAG Shop aces across the board for cleanliness, sanitation and safety. He wrote, “I am proud to have set a standard that has within 2 yrs put us in the Top Shops in Georgia! Thanks to us all: Shay, Quick, Kent, Winston, Marlon, Nando, ‘Rocky’ and ‘T’! #NiggaWeMadeIt! LoL.”

Looking at the faces of the SWAG Shop’s barbers in the 18 photos Mike posted along with the announcement, it’s not hard at all to imagine them becoming business owners themselves. They look young, determined, capable.

And it’s very easy to imagine Killer Mike’s ghetto gospel spreading. As I write this line, Michael Render is preparing to perform in front of thousands at San Antonio’s Maverick Music Festival. At 7:40 p.m. Central time, he will convene his traveling church of rap.

The church will bounce.

The church will rock and roll.

Killer Mike and El-P will give them the opposite of bullshit.

And the church will say, “Amen.”