Lawson Little’s Camera Has Followed Country Music’s Great Migrations for 40 Years

Photography by Lawson Little Words by Chuck Reece

Lots of folks back East, they say, is leavin' home every day,

Beatin' the hot old dusty way to the California line,

'Cross the desert sands they roll, gettin' out of that old dust bowl,

They think they're goin' to a sugar bowl, but here's what they find,

Now, the police at the port of entry say,

"You're No. 14,000 for today.”Oh, if you ain't got the do re mi, folks, you ain't got the do re mi,

Why, you better go back to beautiful Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Georgia, Tennessee.

California is a garden of Eden, a paradise to live in or see,

But believe it or not, you won't find it so hot

If you ain't got the do re mi.— Woody Guthrie

In 1937, in a single song, Woody Guthrie described the westward route that generations of working-class Southerners followed as they sought work and opportunity. Americans usually define the significance of that route purely in terms of what the people who traveled it were seeking. But the westward route is also significant because of what its travelers took with them.

One of those things was music.

They brought hillbilly songs down out of the hills and turned them into country music and bluegrass in the early 20th century. The Southern musical thread wound onward through Texas, branching off into the western swing of Bob Wills and Milton Brown in the 1930s, the honky-tonk dance music of the 1950s and then the outlaw country of the 1970s. It would creep from there on into southern California and give birth to the Bakersfield sound of Merle Haggard and Buck Owens.

Many writers, photographers and academics have made it their life’s work to document these rivers and tributaries of country music, but their work is often confined to sub-genres of the music or particular time periods within it. As far as The Bitter Southerner knew, there was no sweeping collection that documented all the regional offshoots across time.

Then we met Lawson Little. Today, at age 68, Little lives in the East Hill neighborhood of Pensacola, Fla., and says he’s “semi-retired.”

We had never heard of Little until he sent us some photographs. More precisely, hundreds of photographs. When we dug into them, we realized we were looking at something we’d never seen before: a treasure trove — four decades of solid work — documenting the western evolution of country music from Appalachia to California.

Kentucky Farmer, 1966, shot by a teenage Lawson Little

“I grew up in poverty,” Little says. “My parents were from Tennessee and Kentucky. They moved up to Chicago in the war years to do labor in the factories.” In 1945, young Lawson came along and grew up in a poor neighborhood on the south side of Chicago called Back of the Yards. Throughout its history, this neighborhood abutting Chicago’s old Union Stockyards had housed successive waves of immigrants, but during World War II, Back of the Yards had become an Appalachian enclave.

“I had those roots in my life with my parents and my neighbors,” Little says. “I kind of grew up with the music. My mother cried when Hank Williams died.”

He made it out of Chicago’s little Appalachia and eventually studied photography at the Rhode Island School of Design under two legendary American documentary photographers, Aaron Siskind and Harry Callahan. Callahan had been part of the American "extension" of the Bauhaus movement that emerged in Chicago after Hungarian painter and photographer László Moholy-Nagy moved there in 1937. Siskind was most closely associated with the abstract expressionist movement in 1950s New York City.

After RISD, Little took his master’s in fine arts at the California Institute of the Arts in Los Angeles, then began his career as a professional photographer. He soon found himself taking assignments to shoot musicians.

The photos he was hired to shoot were for magazines and record companies and the like, but he discovered he wanted to move deeper into the subject matter.

“It was me bringing black-and-white film with me on commercial jobs,” he says. “A lot of this was work around commercial shoots, where I was covering artists and then I would bring my own camera and my own vision. And I would shoot my own work as I was photographing the artists.”

He was concerned, he says, “about preserving the history of the music — and the evolution from that history.” And the more he hung around the musicians, the more they allowed him to see through his lens.

“When you’re around the musicians constantly, eventually you’re like an old shoe,” he says. “They don’t even pay attention to you. And when you do draw their attention, they’re at ease because they know who you are.”

So he hung around for 40 years. Documenting the evolution of country music became his life’s work. Little is now working with a California publisher, Insight Editions, to bring the photographs you see here — and hundreds of others — into a book to be published in late 2014 or 2015.

“It’s a labor of love. You have to love it to shoot it like this,” he says. “There’s just no way you could do this commercially. They are documentary images, and most people aren’t interested these days in documentary photography, especially in modern, contemporary country music. Everything is so controlled and stylized. You almost can’t get these photos any longer.”

But Lawson Little got them and still does — from the late 1960s through his latest trip to Nashville two weeks ago. And if we never see photographs like these again, every Southern music fan should remain grateful to have discovered Little’s.

The music that came down from the Appalachians to become bluegrass and country is the primary source of one of American music’s greatest rivers.

Bill Monroe

The king of bluegrass gets frisky with a fan, 1972. Monroe died in 1996.

Lester Flatt & the Nashville Grass

Lester Flatt, who brought bluegrass to the masses in the 1960s with his theme song for (and appearances on) “The Beverly Hillbillies,” backstage at Nashville's Ryman Auditorium with his band, the Nashville Grass, 1972.

Dr. Ralph Stanley

The top two portraits of the legendary Ralph Stanley were taken in 1973. He soldiers on today, touring the world with his Clinch Mountain Boys as he approaches his 87th birthday. Bottom right, songwriter Jim Lauderdale and Ralph Stanley in 2000, touring behind their joint 1999 album, “I Feel Like Singing Today”.

Jim & Jesse

Bluegrass duo Jim and Jesse McReynolds came from a long line of Virginia musicians. Their grandfather led a Virginia band called the Bull Mountain Moonshiners in the 1920s. Jim passed away in 2002. Jesse survives. These photographs are from 1972. At right, Jim and Jesse rehearse with Vassar Clements in the Ryman dressing room.

Vassar Clements, Darrell Scott & Tim O'Brien

Left: Fiddler Vassar Clements grew up in pre-Disney Kissimmee, Fla. He replaced the legendary Chubby Wise in 1949 in Bill Monroe’s Bluegrass Boys and went on to apply his mountain fiddle mastery to genres like swing and jazz. He died in 2005.

Right: Darrell Scott and Tim O’Brien, songwriters and multi-instrumentalists, steeped in the traditions of country and bluegrass. They preserve and expand those traditions today.

Del McCoury

Bluegrass legend Del McCoury with his grandson.

The heart of country music settled long ago in Nashville. It’s been there for years, it ain’t going nowhere, and it has brought us some of the greatest songs in American history.

Tootsie's Orchid Lounge

Hattie Bess — aka “Tootsie” — was the proprietor of Nashville’s legendary Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge. Lawson Little shot her early in 1973, showing off her 1972 Christmas present from Marty Robbins, left. Little also captured the shot at right of Tootsie’s legendary back room, the door to which is directly across the alley from the stage door of the Ryman Auditorium. Never have so many legendary Southern feet trod so short a strip of pavement.

Roy Acuff at the Grand Ole Opry

Roy Acuff once declared that if people would not pay to hear him sing, he would make them “pay to hear me holler.” He did, too, serving for decades as the Grand Ole Opry's mainstay. At left, Acuff throws his yoyo at Little’s lens from the Ryman stage in 1972. Acuff died in 1992.

Porter Wagoner

No one ever rocked a Nudie suit harder than Porter Wagoner. He also brought us one of the best killin’ songs in country history, “The Cold Hard Facts of Life.” Wagoner died in 2007.

Johnny Cash and June Carter

At left, Johnny Cash is helped from his wheelchair after his beloved June Carter’s memorial service, 2003. At right, her casket is wheeled away. Cash followed her to the far-side banks just four months later.

Ray Price

Ray Price came to Nashville from Perryville, Tex., in 1951 with perhaps the purest voice of any that will ever grace a country stage. His recording of Kris Kristofferson’s “For the Good Times” is the definitive version, and his immortal 1954 hit "I'll Be There (If You Ever Want Me)” remains a required staple for honky-tonk dance bands everywhere. Price passed away in late 2013.

Bobby Bare, Tennessee Williams and Jimmy Buffett

Bobby Bare’s legendary 1964 hit “Detroit City” told the story of every Southerner who headed north for factory work. “That was like the anthem for us in Chicago, at least for my father anyway,” photographer Lawson Little remembers. Bare was also part of a legendary Key West wrecking crew of writers in the early 1970s, a hard-partying gang that included playwright Tennessee Williams (at left below), journalist Hunter S. Thompson, and songwriters Shel Silverstein and Jimmy Buffett (at right below). Little shot these images in Key West in 1978.

As the river of music washed onward into the West, it morphed into countless tributaries as it flowed through Texas and into California.

Emmylou Harris and Phil Kaufman

Emmylou Harris was born in Alabama and raised in North Carolina, but she first surfaced in the national consciousness singing harmony on Florida-born Gram Parson’s records in California. Parsons was arguably the first to merge country roots with hippie music, calling his drug-fueled tunes “cosmic American music.” When Parsons overdosed and died in 1973, his stepfather in New Orleans arranged for his body to be shipped to Louisiana for burial. But his friend, Phil Kaufman (at right in cowboy hat in this 1980 photograph), borrowed a hearse and stole Parsons’ coffin from Los Angeles International Airport. He drove to one of Parsons’ favorite spots in the Joshua Tree National Monument, pulled the body from the coffin and burned it. There was no law then in California against stealing a dead body, so Kaufman was fined $750 for stealing the coffin. Cap Rock, the spot in Joshua Tree where Kaufman spread Parsons’ ashes, still draws fans.

The Dixie Chicks

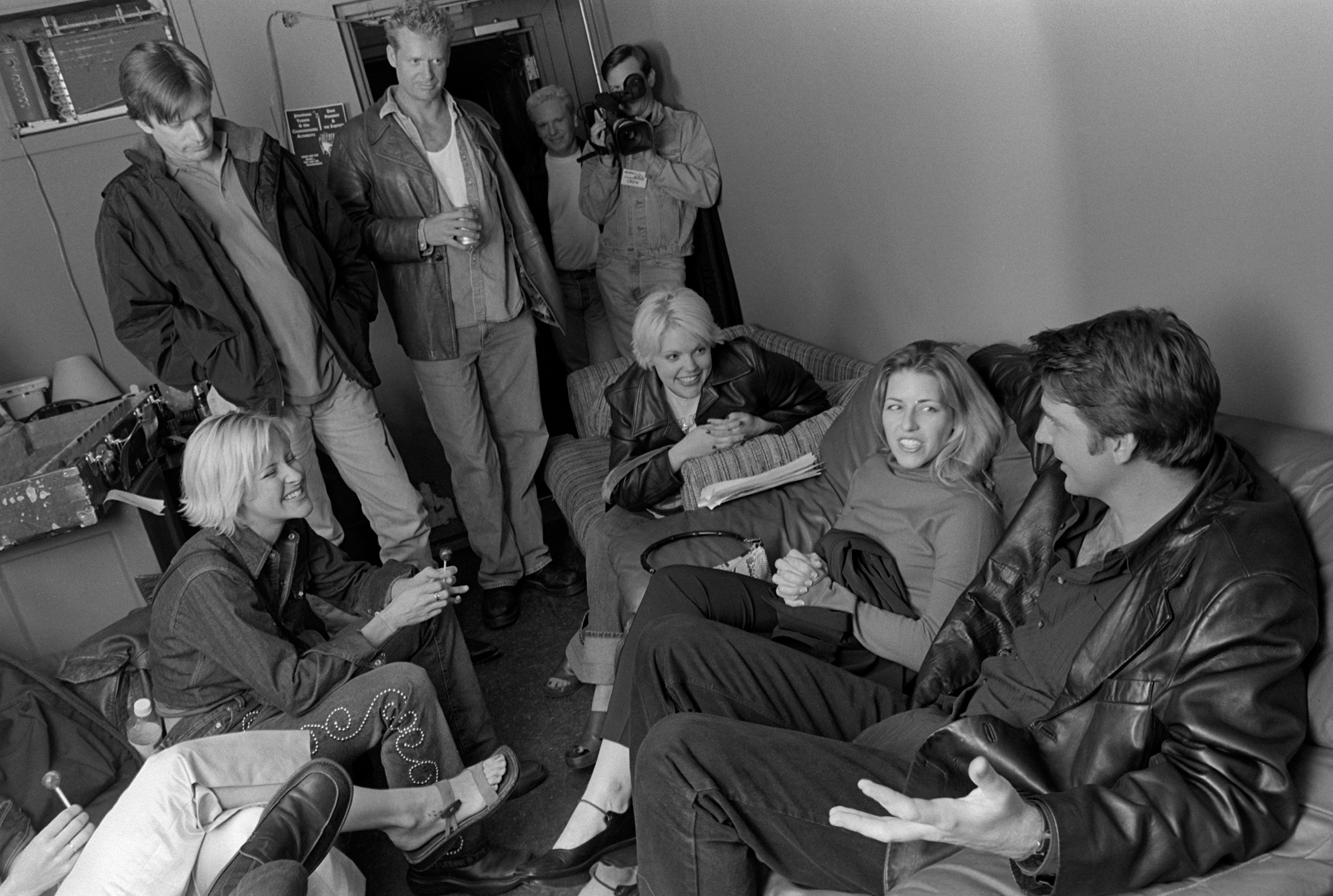

The Dixie Chicks in the dressing room with Austin songwriting brothers Charlie (at top, in open-neck shirt) and Bruce Robison (on sofa at right).

Kris Kristofferson

Rhodes Scholar, Barbra Streisand co-star, Highwayman and legendary American songwriter Kris Kristofferson. Kristofferson, from Brownsville, Tex., is arguably the Gershwin of country music. His hits — such as "Me and Bobby McGee," "Sunday Mornin' Comin' Down" and "Help Me Make It Through the Night," and "For the Good Times" — are American classics.

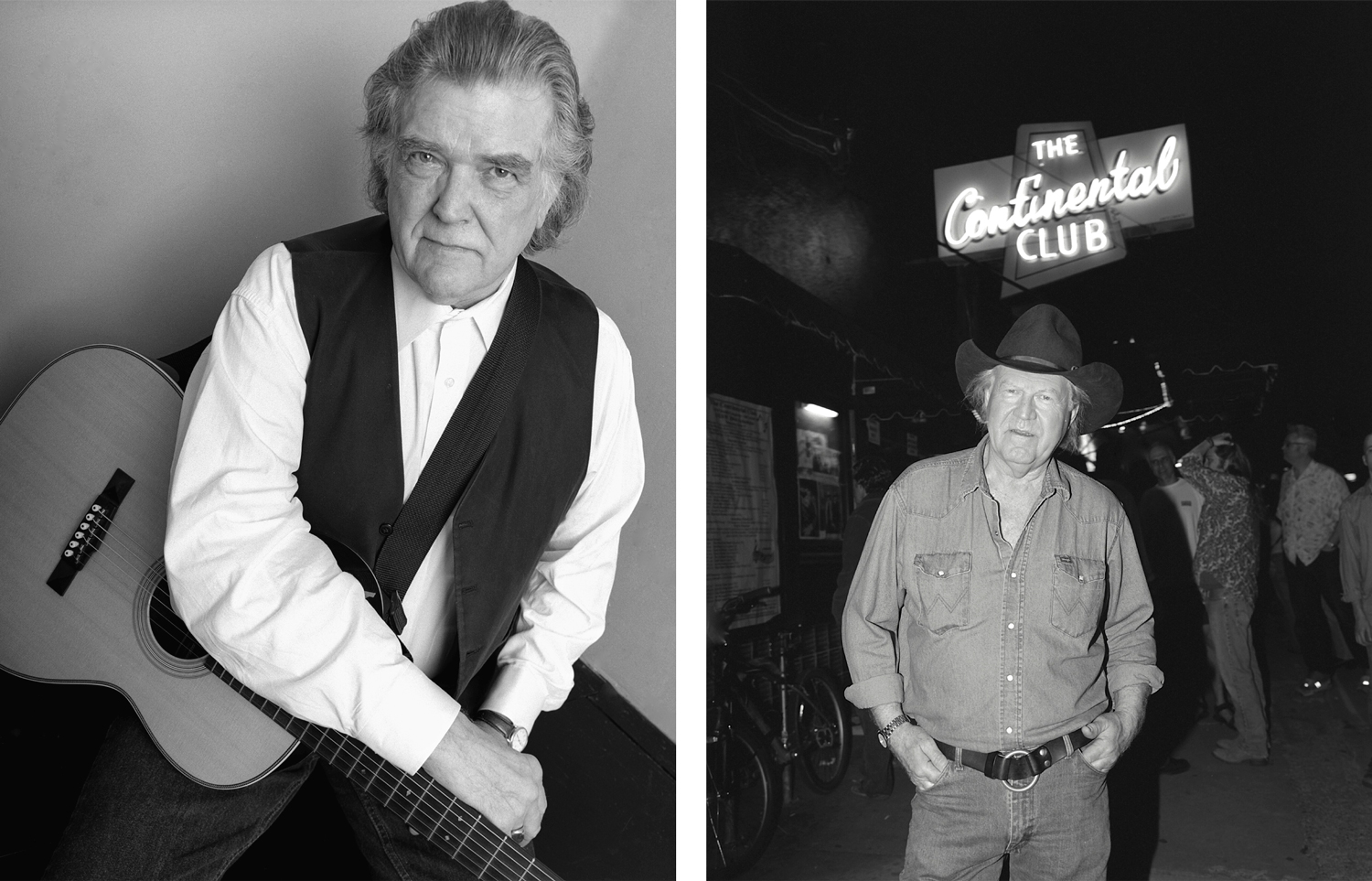

Guy Clark and Billy Joe Shaver

At left is legendary Texas-by-way-of-Nashville songwriter Guy Clark. Young songwriters in Nashville sometimes refer to him as “God Clark,” and not without reason. Clark writes consistently affecting, deeply emotional and amazingly literate songs. His “Dublin Blues” contains one of the strongest and most succinct declarations of Southern cultural validity ever written: “I have seen the David. Seen the Mona Lisa, too. And I have heard Doc Watson play ‘Columbus Stockade Blues.’” At age 72, Clark is fighting cancer, but just won a Grammy for last year’s “My Favorite Picture of You” album.

At right is another Texas legend, Billy Joe Shaver, author of such classics as "I Been to Georgia on a Fast Train" and "I'm Just an Old Chunk of Coal (But I'm Gonna Be a Diamond Someday)," in front of the Continental Club on South Congress Avenue, Austin.

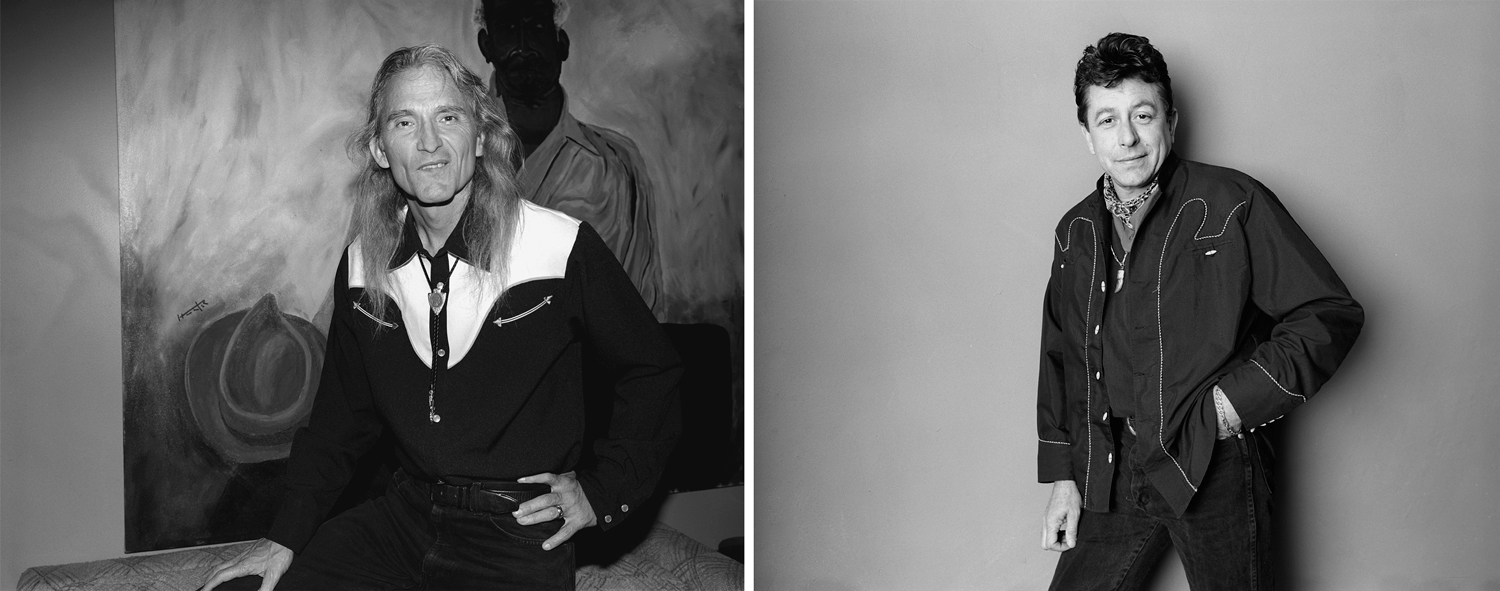

Jimmie Dale Gilmore and Joe Ely

Gilmore, left, and Ely are two of a triad of amazing songwriters who grew up in Lubbock, Tex., and formed the legendary Texas country band the Flatlanders.

Dale Watson, Dave Alvin and Dwight Yoakam

Not only is Austin's Dale Watson, left, a tremendous songwriter and guitarist, he is also a human jukebox of honky-tonk dance numbers. Buy Dale a shot of tequila and throw him the most obscure Lefty Frizzell title you can recall. He will down the cactus juice, then play a letter-perfect version of whatever you've requested.

Dave Alvin, middle, the son of a Downey, Calif., union organizer, has long upheld an entire host of American folk traditions, but he first blazed onto the scene in the early 1980s as part of the Blasters, the hard-rocking band that brought roots credibility into the L.A. punk scene.

Oddly enough, Dwight Yoakam, a Kentucky native, found his first welcome as a country singer in that same Los Angeles punk-rock scene.

In the late 1980s and on through the ’90s, a new generation emerged determined to reclaim country music from the excesses of Nashville production, to bring the music back to its basics.

Allison Moorer

In the 1990s and early 2000s, Allison Moorer and her sister Shelby Lynne made huge waves in country music with their increasingly adventurous albums, which have branched off into rock and roll and Southern rhythm and blues styles.

Buddy and Julie Miller

Buddy and Julie Miller came to Nashville in the early 1990s and turned heads with Buddy’s first album, a hard-country, honky-tonk masterpiece called “Your Love and Other Lies.” The album was a skillfully executed reclamation of honky-tonk music’s deepest traditions, and Miller has gone on to become one of the most in-demand guitarists and producers not only in Nashville, but also in the broader musical world.

Greg Garing and BR-549

Greg Garing, left, was the musician almost singlehandedly responsible for building the late 1990s alternative country movement in Nashville. The young bands like BR-549, right, that formed in Garing’s wake helped bring an economic resurgence to the Lower Broadway section of downtown Nashville, which had fallen into disrepair after the Grand Ole Opry abandoned Ryman Auditorium and headed for the suburbs. Garing leaned toward punk rock for inspiration, while BR-549, captured here in their original incarnation in 2000, went straight back to country music’s elemental past for source material.

Tift Merritt, Jim Lauderdale and Ryan Adams

In the late 1990s, a passel of young acts gave birth to a substantial alt-country scene in North Carolina: the Two Dollar Pistols, the Backsliders, Whiskeytown and an angel-voiced singer named Tift Merritt. From left to right, Merritt, songwriter Jim Lauderdale and Ryan Adams of Whiskeytown.

Old Crow Medicine Show

Old Crow Medicine Show, whose members hail from all over the country, shows the enduring power of old-time mountain music to capture the attention of younger generations.

Juke Joints (and Other Sacred Places)

Follow Lawson Little's journey through the juke joints, honky-tonks and other out-of-the-way spots where the music is preserved and remembered.

A Little Dancin’, a Litttle Cryin’

Thanks to our friend Greg Germani, we have a playlist that will have you dancing around your workplace or wishing you had a beer to cry in.