Thirty years ago, an East Tennessee guy with the unlikely name of Lazarus started the most demanding footrace in the world. The Barkley Marathons were already famous among extreme athletes, and then, a 2014 documentary film brought the wider world’s attention. The story of the race is great. The story of the man behind it is even better. That is, if Lazarus Lake really exists.

By Sara Estes | Photographs by Tamara Reynolds

Sunup on a cold winter morning. Lazarus Lake is standing next to a red Honda at the entrance to Frozen Head State Park in Wartburg, Tennessee, about an hour west of Knoxville. He’s wearing loose blue jeans, a flannel shirt, and a new pair of work boots. His long gray hair is pulled into a ponytail that hangs down his back. At a glance, he looks like a retired truck driver or a felon-turned-farmer.

“You’re late,” he grumbles. It’s 7:03 in the morning.

I hustle from my car to where he’s standing and apologize. He seems cold, distant, mildly annoyed by my presence. I’m not picking up an ounce of the humor or charisma I’d heard so much about. Maybe it’s just me. I’m here because he reluctantly agreed to let me tag along with him and his crew on their hike to the top of Bald Knob, the highest peak in Frozen Head. I explained that I was writing a big story on the Barkley Marathons — the world-famous ultra-marathon Lake founded and his life’s magnum opus. He wasn’t the least bit affected by the news. In fact, he seemed a little annoyed.

The seven-hour trek up Bald Knob, I am told, is far better than scaling Big Hell, Rat Jaw, or Bird Mountain. It’s better than The Bad Thing. We won’t have to cross Son of a Bitch Ditch, a 10-foot-wide, 10-foot-deep gouge in the dense forest. We’ll avoid Leonard’s Butt Slide, which propels you down at 45-degree gradient through several hundred feet of mud and saw briars.

I’m dressed like I am about to footslog through the tundra: long underwear, long-sleeve wicking shirt, sweatshirt, hoodie, overcoat, blue jeans, leg warmers, gloves, earmuffs, and a red toboggan. I heard the weather can get down to freezing at the top of the peaks of Frozen Head, regardless of how tolerable the temperature is at the bottom.

We set out on the hike in silence. I linger a few paces behind Lazarus and his friend and colleague, Raw Dog. Thirty years ago, these two woodsmen founded the Barkley Marathons, a now infamous 100-mile footrace through some of the most unforgiving terrain in the country. Known to its many disciples as “the race that eats its young,” the Barkley is considered one of the most difficult ultramarathons in the world. The best runners in the world have tried and failed. Out the 1,000 or so runners who’ve attempted the race, only 14 people have ever finished. With 59,100 feet of climb, it’s the equivalent of climbing Mount Everest…twice. That’s more than any other ultramarathon — more than the 33,000 feet at Hardrock or the 45,000 feet at Nolan's 14. Most people refuse to believe a race held in the Tennessee backcountry could be so punishing, but to every runner’s complete dismay, it most certainly is.

Since 1986, the Barkley has been operating entirely under the radar, rising from a casual underground affair to a cult obsession. Few even figure out how to enter the Barkley, fewer still come close to finishing it. Today, people come from all over the world for the chance to annihilate their minds and bodies in a 60-hour, 100-mile, sleepless, nearly impossible gauntlet through the merciless mountains. Lost and alone, they struggle through hallucinations, extreme cold, heat, thunderstorms, sleet, and rock-bottom exhaustion while they navigate vast stretches of sinister, unmarked woodland with only a compass and their prayers.

Year after year, a new mêlée of poor souls offer themselves to the Barkley gods. They volunteer to plummet into the depths of mental and physical agony crossing questionable waters, gaping ravines, and brutal cliffs in the dead of night. They train for years, for decades, to vie for a spot they usually don’t get, then puke, bleed, and hyperventilate alone in the woods until the moment their body collapses or they make the decision to give up and go home with their hope and pride dragging like empty cans behind them.

And for what? For the chance to be anointed to the highest of ranks, for the chance to become something more than human, something unbreakable and invincible, for the chance to have their fearlessness fossilized in the annals of a near-impossible feat, and above all else, the reason they do it is for the chance to prove their worth, not to themselves, but to the figure they worship and revere.

The Bearded Saint. The Godfather of the Woods. His hallowed name, a single syllable: Laz.

The truth is, I didn’t realize what I was getting myself into when I took the assignment to write a piece on the Barkley Marathons. I didn’t know that I would end up venturing out into the vicious terrain myself. I hoped I might just be able to watch from the sidelines, cheer on the waning runners as I scribbled observations about endurance, prison culture, punishment, and the vast peculiarities of Southern culture. But as I got more involved with the people in the race, my perspective began to shift. The more I got to know him, I started to see Lazarus Lake in a strange new light. My story was not about the race at all.

It was about a man named Gary Cantrell.

On the ascent to the peak of Bald Knob, Laz’s eyes are fixed like a hawk’s on the rocky trail. He continually scans the ground for fossils, animal tracks, and rare stones. It’s been about half an hour of hiking, and he’s starting to warm up to me a little. He shares his extensive knowledge of geology in bits and pieces. He gabs about local landscape and the history of how this land was formed. He talks about Tennessee’s three radically different geological zones, the rare flat limestone in the central U.S., and the uplift mountains that were created when the Smokies shoved across the continent 300 million years ago.

“If you look at the eastern U.S., from way up on the topo, it looks like you pushed a box across the carpet, and rolled the wrinkles in front of it,” he said.

It’s easy to see why a place like Frozen Head would keep him interested all these years. The park is an anomaly. The ground is striated in flat limestone, sandstone, shale, and coal. Hoarfrost collects on bare branches like a million glass daggers, majestic and menacing at the same time. Frost-covered spider webs look like white lace tapestries strung sweetly between the trees. And while there is beauty in a few pockets of the park, much of the land is brutal and bleak. In a word: uninspiring. And that’s a major part of what makes the Barkley so difficult. There are no stunning vistas and verdant flora in early spring when the race is held. It’s wintry and barren with blankets of blinding fog. The landscape is a grey-brown slough covered in soggy leaves and years worth of brittle tree limbs. They look like millions of gray scratch marks on the ground, like something was clawing to get out. Trees like steel bars, thickets like razor wire — it is no stretch to say it’s a certain kind of prison.

Laz is slowed by a limp in his right leg. He’s 62 years old now. A life-long marathoner, he ran over 100,000 miles in 50 years. He’s got the map to prove it, marked and highlighted with a network of road and trails. It helps him keep track of everywhere he runs. After so many miles, and a series of unfortunate injuries, he has a few tips on the sport.

“You don’t have to eat to run,” he tells me. “That’s an old wives tale. We were designed for feast and famine. Most people of who have lived have been hungry most of the time. There’s either plenty or there’s nothing.”

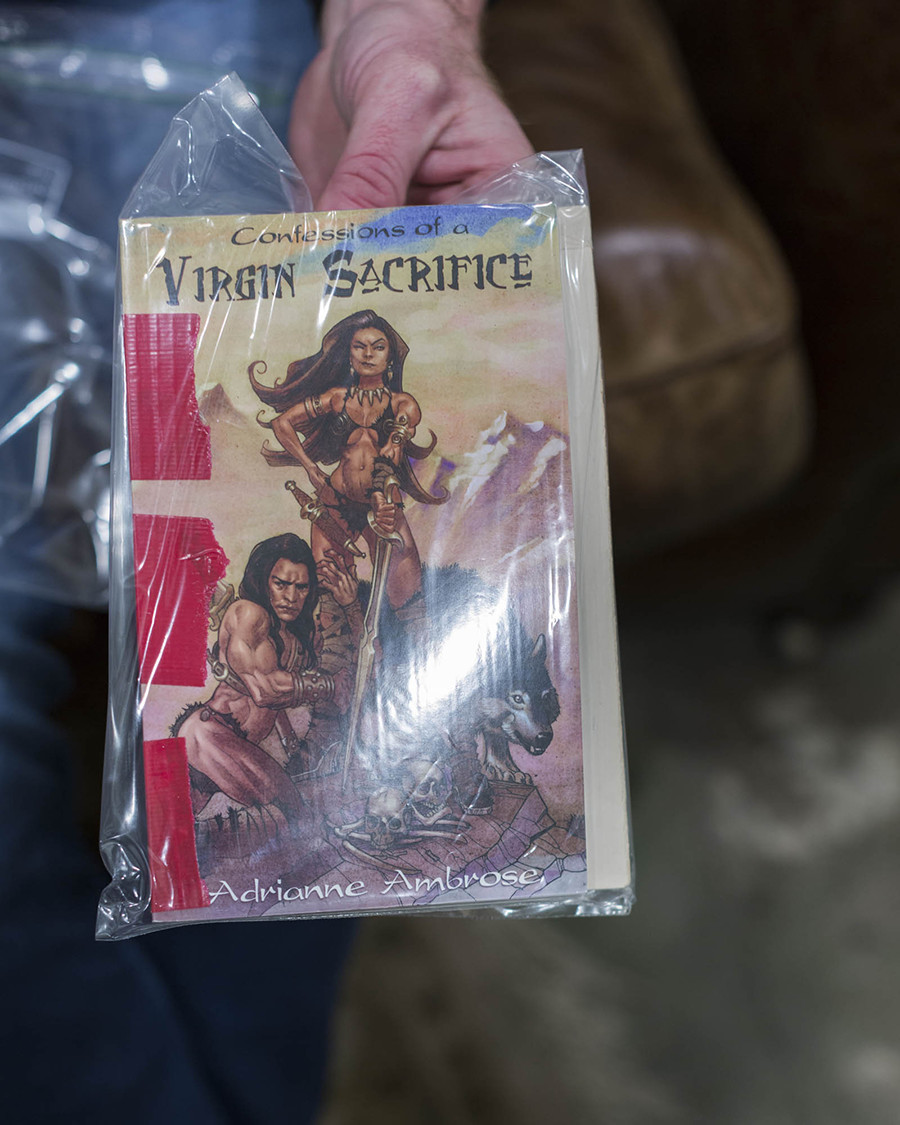

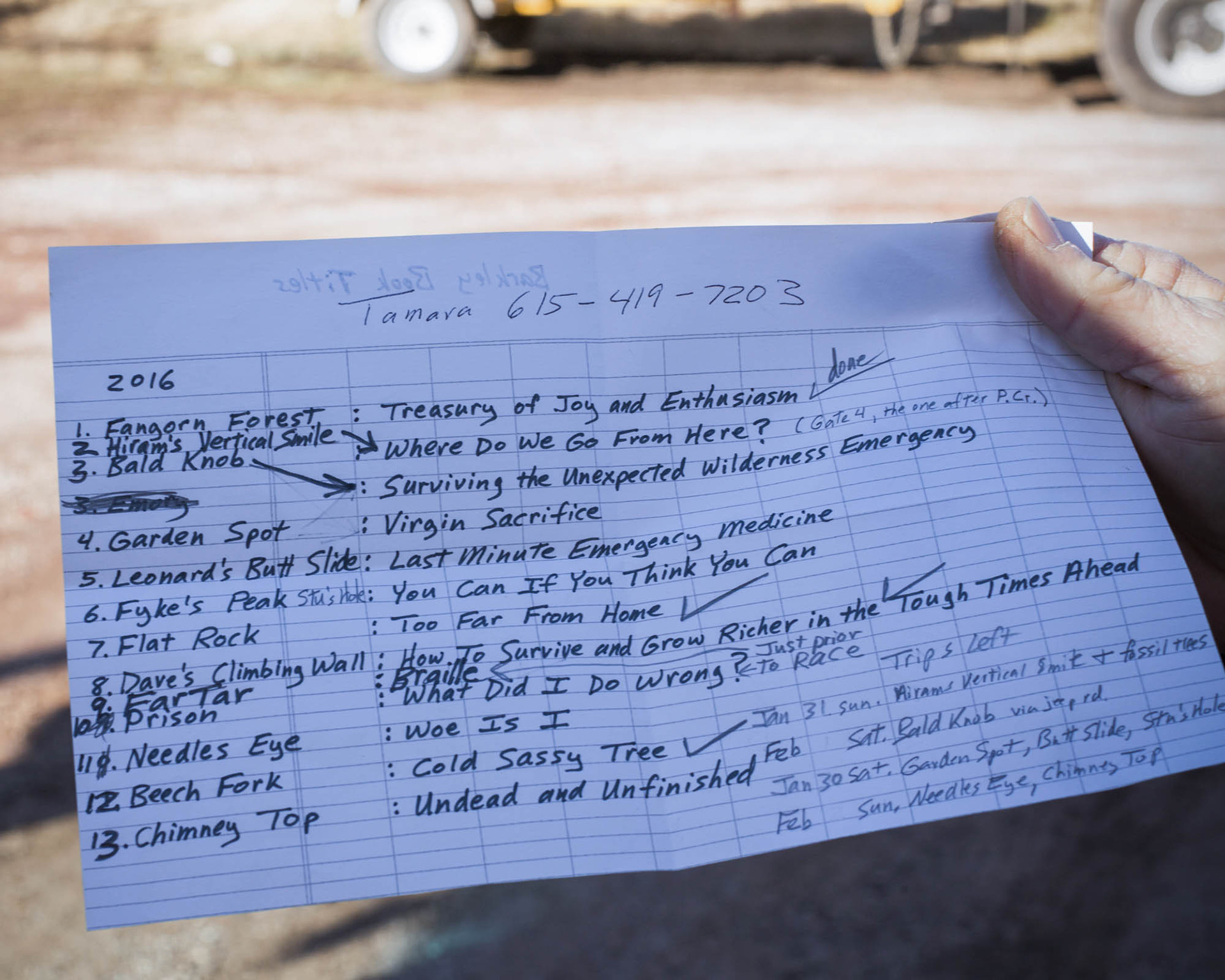

We’re climbing over 2,000 feet to do what they call a “book drop.” The Barkley is entirely unmarked, so Laz and Raw Dog hide books throughout the course to serve as benchmarks. When a runner gets to a book, she tears out the page that corresponds to her number, and brings it back to Laz as proof she completed the full loop. It can also help them locate a missing runner. By finding the last book page the runner tore out, search parties can narrow down where the runner might be. Though they typically won’t go looking for someone until the full 60 hours are up. There are 13 books this year. The titles include: “What Did I Do Wrong?,” “Confessions of a Virgin Sacrifice,” “You Can if You Think You Can," and “How to Survive and Grow Richer in the Tough Times Ahead.”

I ask him, why books?

“What else has page numbers?” he says. His cute pragmatism is a big part of his charm. He says the titles also serve as “entertainment.” One year, to the runners’ surprise, all the books were pornos. The Barkley has become so widely known for the tongue-in-cheek book selections that people now send him books in the mail — so many that he doesn’t have to buy them for the race anymore.

On the side of the mountain, Laz stops in front of a faint impression of a paw print in the dirt.

“Can you tell dog tracks from coyote?” he asks, looking up at Raw Dog. “I can tell the skulls apart, but not the tracks.”

Raw Dog steps over to look at the print. “Dog,” he says in a soft voice. We continue walking. They often feed off each other like this, quizzing the other’s encyclopedic knowledge of the outdoors. When Laz points out a patch of rhododendrons, Raw Dog says, “Those are mountain laurels.” Laz suggests hiding a book in a birch tree, and Raw Dog says, “Now, Laz, that’s not a birch.” They’ve turned the wilderness into a scholarly pursuit, a form of art.

“Have you ever seen rose rock?” Laz quizzes me. “They are crystals formed in sandstone. They look like roses. I lived in Norman, Oklahoma, as a little kid, and it was one of the few sites that had them. We’d just pick them right up off the ground.”

Laz, whose real name is Gary Cantrell, spent his formative years, age 6 to 9, in Oklahoma. It was the first place that felt like home for him.

“There’s no hills, there’s no trees, and the wind blows all the fucking time — 15 to 30 miles per hour. Six months one direction, and for the next six months, it blows back,” he says

Gregarious by nature, Laz talks about everything. He is encyclopedic and funny, an endless fountain of information, anecdotes, and jokes. He never misses a beat in conversation. I’m starting to see why so many people are fascinated by him.

He tells me he moved around a lot as a child. His family came to Tennessee when his father got a job as an aerospace engineer in Tullahoma. For a boy who didn’t have much in the way of stability, it makes sense that he would be so fascinated with things like rocks and fossils — solid, permanent things.

I search the ground, too, but I’m not entirely sure what I’m looking for. Shiny bits of black glass shimmer beneath our feet. I bend down and pick up a piece about the size of a cigarette lighter. I hold it out in the palm of my hand.

“What is this?” I ask.

“That’s coal,” he says. “They’ve torn the mountains to pieces and destroyed the environment for that shit.”

I ask if it would burn if I lit it on fire. He says yes. Oh, yes.

The next time I meet up with Laz and Raw Dog, it’s early on a Friday morning for the final book drop at the Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary. Laz instructs a group of us to meet him at the Hardee’s in Wartburg. It is April Fool’s Day and, by no coincidence, the official start of the Barkley weekend.

The race will begin sometime between midnight and noon on Saturday; no one knows exactly when. All they know is that at some point in those 12 hours, Laz will blow a conch shell, which means the runners have exactly one hour to be at the starting gate. The race starts when Laz lights his cigarette. This keeps runners on their toes. Laz likes it that way.

When I arrive at Hardee’s, the sun still hasn’t risen, and the air is chilled and dew-damp. Inside, a group of white-haired men — retired, church-going, grandpa types — are seated around a large table in the middle of the restaurant. They’ve been eating breakfast here, every morning, at this very table, since the dawn of fucking time. They can remember all the various phases of branding and décor Hardee’s has cycled through over the decades; they can recount what year the restaurant got new booths, new light fixtures, new flooring. They know the Barkley well, and can always tell its arrival by all the strange new people who flood into the small town around April Fool’s Day, the day on which Laz purposefully chose to host the race, or as near to it as possible.

When Laz arrives, he orders sausage and eggs and joins the men at their roost. Media crews from France and New York are slowly trickling in. They look like aliens from a distant land with their hi-tech AV equipment and tight-fitting athletic wear. Laz ignores them. His particular brand of grungy, mountain-man fame is generally underwhelming to locals, yet ceaselessly exhilarating to clean-cut city dwellers near and far.

“In France, I’m a star,” he tells me. “In America, I’m thought of more as a homeless person.”

Last year, two independent filmmakers, Timothy Kane and Annika Iltis, made a documentary about the Barkley. Released on Netflix, it was a hit. Laz says the film got local people interested. Already, about 10 people from media outlets like CNN have shown up to start tracking Laz’s every move during the weekend.

“There’s a lot of attention on the event this year, and I have to go in front of all this media between teeth,” he says with a laugh. Shortly before the documentary came out and his popularity soared, Laz pulled his own teeth. He didn’t want to go to the dentist, so he decided to self-extract. He then advised that it would be good prep for the Barkley to pull your own teeth.

Teeth or no teeth, Laz doesn’t shy away from the camera. He’s is a man of taglines, quips, and one-liners — a fact that belies his general appearance. Thus, the cameras love him.

As I spend more and more time with Laz, I start to see the character he’s constructed over the years. Laz’s public persona is a well-oiled machine. And it made me wonder: Who the hell is he really? Everyone worships him, and he’s built this cult fan base. What is it about him that makes everyone want in?

We’re at the infamous Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary, a 120-year-old maximum security prison in the nearby town of Petros, Tennessee. Buttercups and thistles frame the area in front of a towering metal entry gate. Even in their semi-wilted state, the flowers seem deceiving or sarcastic, like a throw pillow on a bed of nails.

Laz pulls up in a U-Haul and assures us the “woman with the keys” is on her way. His dog Little eats grass and throws up on the gravel. A few minutes later, Lisa Rutherford, a woman with short blonde hair drives up in a white truck. With a hoop of keys jangling from her hip, she slowly walks the gate open.

“Welcome to the end of the line,” she says.

For well over 100 years, Brushy Mountain served as one of the largest maximum security facilities in America. It closed its doors in 2009. Hidden in the rugged Cumberland Mountains, “The Castle,” as it’s known to locals, was built in 1896 and housed the most dangerous criminals of our time. The merciless land surrounding the prison made it the ultimate site for a lockdown. A TV news reporter once said it well: “Getting out of a prison is one thing, but getting out of Morgan County is something else.” As turns out, the story of one prisoner’s botched escape is the sole reason the Barkley exists.

James Earl Ray, who assassinated the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., escaped from Brushy Mountain in 1977 while serving a 99-year sentence for the 1968 murder. The first person to ever escape the prison, Ray and six other convicts escaped by fashioning pieces of pipe into a makeshift ladder, which they flung over a 14-foot wall. Two other inmates staged a fight to distract the guards while they made their way over the wall. Ray was found by bloodhounds and recaptured 55 hours later. In that time, two days and seven hours, he had only managed to get eight-and-a-half miles from the prison. Exhausted and covered in mud, he was returned to Brushy Mountain.

Inspired by the story of Ray’s attempt, Laz and Raw Dog wagered a mocking bet that someone could probably travel a hundred miles in those woods in the same amount of time. Thus, the Barkley was born.

After Laz duct-tapes a book to a metal bar behind the prison walls, we all slink around the creepy abandoned grounds: the basketball court, the laundry rooms, the windowless rooms used for solitary confinement, the gym built by inmates with rock from the quarry.

“There’s a theme to the décor,” says Laz. “They’re into locking you in.

Lisa takes us up to the old cafeteria, where, in 1998, an inmate named Tim Cross painted a series of murals that run around the entire room. There are gorgeous renderings of mansions, candlelit cottages, wildlife, fish. Like the buttercups outside the barbed wire gate, there’s something deafeningly tragic about the painted scenes.

Next, we walk to Cell Block A, where James Earl Ray served his time in Cell 27. We take turns surveying his living quarters. Scratched on a metal desk is the phrase, “God Loves You.” On the door, a hand-drawn confederate flag. I point out the image on the door.

“People are complex,” Lisa says.

Some people question if the Barkley is really a backward tribute to the man responsible for killing one of the greatest civil leaders of all time. It’s a valid question. Is there some kind of racist undertone to the Barkley? I wondered myself. The South is notorious for having seemingly innocuous traditions that have roots in deeply unsettling beliefs. When I confront Laz about it, he just laughs. He says it’s always been intended to make fun of the guy, to show what a pansy he was. I think Laz is being honest about that.

Laz routinely uses the word “punishment” in reference to the race. He says it’s not punishment unless you run the whole loop. Punishment is built into the vernacular here. There’s almost a humor in watching someone suffer. That’s what the Barkley is built on. The multiple loops force runners to decide four grueling times to go back out into the wilderness. They have to come back to camp, to their friends and family, to their sleeping bag, but they can’t stay for more than a few minutes. That’s why most runners keep their sleeping bags rolled up for the duration of the race. To not be tempted.

“The ghosts get upset when we tarry too long,” Lisa says. Before we leave, she informs us of their plan to make moonshine in the prison — blueberry, blackberry, and butterscotch. They’ll call it End of the Line Moonshine.

Friday night is the chicken feast. Laz and the other organizers have spent all afternoon setting up the sign-in tent, the license plate wall, and getting all the runners checked in. As everyone settles into their campsites, massive chicken thighs marinated Sam’s Choice BBQ and Frank’s Red Hot Sauce sizzle on the grill all night. When one comes off, another one goes on. Two industrial-sized cans of baked beans lean against a stump. All the regular Barkley attendees bring food, pot-luck style. At some point in the evening, a woman shows up to the feast with a birthday cake that says “Good Luck Morons.”

Laz and Raw Dog’s dark senses of humor define every aspect of the race — from its rules, entry fees, and traditions to the otherworldly camaraderie that exists among the generations of so-called “Barkers.” Over 700 people applied to run the Barkley last year. Only 40 were chosen.

They’ve flown in with their friends and family from all over the world for this. Finland, Netherlands, Sweden, five from France, Australian, New Zealand, Brazil, Bolivia, Canada, New Caledonia. In its history, the race has brought in runners from India, South Africa, Mexico, Taiwan, Tajikstan, Japan, Ukraine, Lithuania, Russia, Hungary, the Antarctica Science Station, the list goes on—and all the US states except maybe North Dakota.

“They’re hard to discourage; you can’t know what it's like,” Laz says.

Back in February, the chosen runners each received a letter from Laz informing them of their selection. In the letter, he assures them their participation in the Barkley will “amount to nothing more than an extended period of unspeakable suffering, at the end of which you will ultimately find only failure and humiliation.” He advises they can spend the months before the race training, but the time would be better spent putting their affairs in order. “Update your will, visit with friends and relatives, and otherwise tie up any and all loose ends. Should the unfortunate mental condition which led to your application for the 2016 Barkley Marathons improve, you might still escape by simply writing me and asking that your slot be passed along to some other unfortunate fool.” He signs the letter, “May your god go with you, Laz.”

Each year, the entry fee for the race is $1.60 and whatever random item Laz specifies: gold-toe dress socks, button-down shirts, a pack of Camel cigarettes. Last year it was flannel shirts, which is why he’s always wearing a new one. This year the fee is “a cool T-shirt with foreign writing on it.” Virgins, or first-time Barkley runners, always have to bring a license plate from their state or country to be added to the wall of plates. As the runners make their way to the sign-in tent, they all bring him the required shirt, the pocket change, and often another thoughtful and doting gift: rare coins from New Caledonia, a hand-painted portrait of Laz on the back of a license plate. A corporate bigwig from Nutella brings him a custom jar that says “Lazarus” instead of “Nutella.” In return, Laz gives them their numbers, some vague course instructions, and a sheet of funny projections for how they’ll do in the race.

As they sign in, I ask the runners why they’ve chosen to do the Barkley over other marathons. They all have one answer: Laz.

Kim, a 33-year-old first-time participant tells me, “It’s all him.” Steve, who has run the Barkley seven times, says, “You can’t replace a guy like that. He’s one of a kind. Laz is the Barkley.”

Kim is one of the eight female runners this year. No woman has ever finished the race, though they continue to sign up each year. I ask one woman if she felt like it was possible for a female to finish. She says she doesn’t think it is. I ask a lot of women the same question, and, to my astonishment, they all agree, citing the physical limitations of a woman’s stride and build. Laz explains that the top male runners in the world finish the race with only minutes to spare. The most recent finisher — Jared Campbell in 2014 (no one finished in 2015) — came in just six minutes before the 60-hour cutoff. Laz says women just aren’t fast enough. Yet still, against all odds, a handful of brave souls were willing to give it a shot.

When the runners are checking in, I notice Laz’s hands. They are exquisite. His nails are perfectly manicured and the skin looks baby soft. It seems entirely incongruous with his mountain-man persona. He tells me that in his other life, he’s an accountant. When you’re pointing out numbers on paper, he says, it’s important to have to nice-looking hands.

In this moment, the division between Gary Cantrell and Lazarus Lake starts to reveal itself.

At 9:44 a.m., Laz blows the conch shell. The park is abuzz in preparation. Everyone has been restless with anticipation since midnight. Runners start warming up, jogging around the campsite. By 10:30, most people have gathered around the starting line: a yellow gate that’s grimy with years of hope and defeat. How many hands have touched it?

“This is the biggest crowd we’ve ever had,” Laz says to me. There are about 50 people standing around the runners.

Someone asks, “Is there an ambulance?”

“There’s one at the ambulance station,” he says dryly.

Laz clears his throat for some announcements before the marathon begins. He tells the runners that should they decide to cross the threshold of this gate, they should “make peace with your god” beforehand and ensure that all of their affairs are in order. He says that participating in this marathon will be the worst decision they had ever made, and he promised no one would tell a soul if they dropped out now.

“You’ve got 24 seconds to do the right thing and go home,” he says to the runners.

Then his tone moves from jocular to serious and heartfelt. He lists several names of runners and friends of the Barkley who’ve passed away. “I want to read their names because they’re not here with us today, and they’re not going to be here with us again, but a little bit of them is out there.”

There is only a one minute left. Things fall to a hush. Runners become still. I hear one guy whisper to his wife, “This is so surreal.” Everyone’s eyes are on Laz, waiting for him to pull out a pack of smokes and light the starting cigarette. The irony of this scene is funny — all the lithe, non-smoking health nuts waiting with bated breath for this grungy dude to light up. Laz finally pulls out a cigarette, casually lights it, and the runners are off.

“There are less than 60 hours to go now,” Laz says with a smile.

The marathon itself consists of a 20-mile course through the woods. Participants are required to run five loops of that course, totaling 100 miles, alternating between clockwise and counterclockwise. According to Laz, it confuses the senses and ensures that runners never get a real handle on the course.

In my conversations with runners, this is what I learned about the Barkley experience. It taxes every aspect of their humanity. It touches their sense of teamwork, sense of humor, their compassion, and their ability to recover from deficits big and small. It’s far more than a physical challenge. They’re deciding about navigation continually; they have to know where they are at all times. When the runners arrive in Frozen Head, none of them know what’s out there. They can’t. There are things there that you won’t find anywhere else. Every part of them is required, without error — and if they make an error, it’s compounded quickly. Most trails and ultra-marathons have aid stations, cut-off times, and trail markers, so that if you train properly, you can do it. But not the Barkley. No amount of training can prepare the runners for it.

There’s a deep kernel in our shared human experience here. If you think about it, moving and walking is the very first thing we do. Aside from maybe digestion and involuntary activities, running, hiking and walking is what we do best. Two-time finisher Jared Campbell said that on the Barkley course, he felt stripped down to his elemental pieces, a sentiment that is echoed in various forms by many runners. At some point, every one of them finds themselves alone in the dark. They’ve got somewhere between 12 and 40 hours before they see another person, and they’re deeply fatigued while dealing with pain, fear, and joy. No matter how trained a runner is, there’s a devil on their shoulder saying, “This is for the birds.” The constant stream of self-doubt is loud in their heads. One must make the decision to go on every second of every hour. According to one runner, when you’re out on the course, there’s nothing else: All you can focus on is moving forward.

“There’s a lot of self-discovery out here, whether you’re running or not,” one runner said.

“What I thought was enough, wasn’t enough,” said a runner who came back after 16 hours on the course, unable to finish even the first of five loops.

As runners trickle in over the course of the next 24 hours, they bring their book pages to Laz and reluctantly decide to go out again. By the second loop, half the runners have given up. Only four of the eight women complete the first loop. Jennilynn Eaten, a 29-year-old from Salt Lake City, is the only woman among the seven runners who attempt a third loop. She and three other runners don’t make it, though. The only three runners who complete the third loop are first-timer Gary Robbins, 39, local boy John Kelly, 31, and Jared Campbell, 36, who finished the Barkley in 2012 and 2014.

By Monday morning, two days after they started, two runners, Kelly and Campbell, have come in from the fourth loop and set out on the fifth and final loop. The campsite crew is waiting on John Kelly — who is so local one of the mountains is named after his family — to come in from the fourth loop. Time is dwindling now. When they finally see him, he has around 12 minutes to come in and turn around and get back out on the trail.

Any longer than that, and completing the fifth loop will be impossible. He’s barely walking. He has a walking stick in his right hand, another stick is dragging from his left wrist. His face is as white as paper, expressionless, gone. Everyone starts yelling and shouting about the time. He rests his body on the grimy yellow gate, and it’s clear he is not going to go back out on the trail. His crew starts gathering food. His wife is alert. She’s trying to help turn him around emotionally, trying to bring his spirits up. He can’t eat. They hold a bagel with cream cheese up to his mouth, but he won’t eat it.

“I need to sleep,” he says in a weak mumble. “I want to go to sleep. I should’ve slept when I was on the last loop.”

Everyone responds with encouragement, telling him he can sleep soon, but he needs to get his number first. He needs to at least start the fifth loop, even if he doesn’t finish. “You can sleep right there,” someone there, pointing at the ground just beyond the gate.

Laz stares at John’s vacant eyes and gives him the number purposefully. John purposefully takes it, and slowly walks around yellow gate. He saunters about 100 yards up the hill and starts circling around a spot on the ground like a dog. He lays down and goes to sleep.

Everyone watches him sleep. Laz walks away, saying nothing.

“We’ll call that the Upper Kelly Campsite,” says a spectator who finished the race a few years back. People laugh and go back to what they were doing.

John stands up after about an hour, dry-heaves, walks straight up Bird Mountain, and retrieves his final book page.

My friend Tamara, who has been taking photographs the whole weekend, goes off in search of Laz to ask him a question. When she finds him, he’s sitting in the back of his U-Haul. His eyes are teary and bloodshot. He looks like he’s crying. She asks him if he’s OK.

“We just experienced someone giving everything they’ve got,” he says. His voice is quivering. “I’m sorry. I’ve got to compose myself.”

She realizes this the first time she’s seen the persona of Laz fall to the wayside. This is Gary now. Laz has left. But the moment, brief as it is, is too vulnerable, too real. Immediately, he makes some sort of joke. Just like that, Laz punches through. He’s back. Gary’s gone.

Around the 55-hour mark, Gary Robbins hitchhikes back into camp. The sounds of “Taps” playing on the bugle echoes through the campsite.

“For 55 hours I gave myself to the Barkley, heart, soul, mind and body,” Gary wrote on his blog. “I was all in. Nothing else in the entire world mattered for three full days, and I loved it. I did not reach the finish line of the Barkley Marathons but I got pretty damn close. As I mentioned leading into the race I knew it would challenge me in new and unforeseen ways and boy o boy did it ever. During the race I feel like I unlocked a door in my mind that led to a room I'd never entered before and in that room existed a near perfect version of myself, devoid of ego, free of judgement, removed from life's minutia, steadfast in purpose, distracted by nothing, heart wide open with a complete inability to overreact to any obstacle that stood in my way. I wish I could be that person more often.”

Late Monday night with only minutes to spare before the 60-hour cutoff, Jared Campbell drags his body around the bend and places his hand on the yellow gate, becoming the only person to finish the Barkley three times. He clocks in at 59 hours and 30 minutes.

I visit Gary at his home several weeks after the Barkley. I want to know what he’s like when the race is over, when he’s not having to play the part of Laz. He lives out in the country, amid miles of rolling green hills, in a gorgeous home he built himself. He designed a lodging room on the second floor filled with beds specifically to house runners. His two dogs, Little and Big, roam freely around the property. After a back injury, he picked up dry stone masonry in lieu of other, more boring methods of physical therapy and rehabilitation. He built all the stone walls and steps on the property himself.

Gary and Sandra invite me inside. They are warm and open. Sandra invites me to sit on the couch, as she pulls out dozens of photo albums. Gary sits in a recliner in the living room as we thumb through decades worth of pictures: marathons, former homes, the children when they were little. One photo shows the family standing in front of Beach Hall Mansion, a dilapidated plantation house they lived in for a while. Sandra says there was no running water or heat. They made do, Sandra says fondly. Gary says he used to pick up their kids’ toys from the road. He remembers a one-armed Skeletor being a particularly great find. In the photos, the young family looks bright and happy. Today, the couple flirts and jokes around in a way I imagine isn’t too different from when they were in their 20s. Sandra tells me about Gary’s love of jigsaw puzzles and his decades coaching Little League Baseball. Expecting a sarcastic response, I ask him what he thinks of the kids these days.

“People badmouth kids,” he says, “but today’s kids are great.

After a few hours of combing through their past, Gary gets up to make us his “famous” cheeseburgers. He uses Serrano peppers and his secret ingredient: curry powder. But before he starts cooking, he brings out a stack of books. They’re books he’s written about his relationship with his dog, Big. Standing at the kitchen counter, he tells me the story of how he found Big in the woods near his house. The dog had been shot and was waiting to die, Gary took him and nursed him back to health. He says it was one of the most profound experiences for him, and since then, he’s chronicled his days with Big in the four-part book series, called “Big Dog Diaries.”

As we’re sitting down to eat, I finally get to ask the question I’ve been waiting to ask this entire time. What’s the story behind the name Lazarus Lake? I’m expecting some staunch biblical reference that points to the story of the rich man and the beggar Lazarus, or Lazarus of the Four Days. As it turns out, it’s just the name of someone who accidentally e-mailed him. Some time after he’d adopted the name, he was running through a small town and found the name again in a phone book. After some research, he discovered a real guy named Lazarus Lake. He was a farmer who lived in Boliver, Tennessee. He was born in 1922 and died in 2009 at the age of 87.

Before I leave Gary and Sandra’s house, I take one last look at the photo of Laz in the big white house: making something out of nothing. I think of all the kids he’s coached in Little League, and the runners who’ve pushed themselves to do amazing, impossible things.

While I’m really not one for cheesy endings, I simply can’t help but wonder, as I’m pulling out of their driveway, if the people who can make something out of nothing are the ones who become legends.

Perhaps the reason we seek their approval, their validation, want to be near them, taken under their wing, is because maybe, just maybe, they’ll make something out of us, too.