Out Behind the Barn

Come Saturday, it will be Derby Day, and Churchill Downs will teem with expensive haberdashery. But the real magicians of Kentucky’s racing country work in a place they call “the backside,” where splendor is beside the point. Here, it’s just a man or a woman and a horse.

Those under the impression that horse racing is all seersuckers and bourbon have clearly never passed a morning at Wagner’s Pharmacy. The no-frills, multi-faceted establishment (which functions simultaneously as a diner, grocery, and pharmacy) has been a cornerstone of the racing community since its doors first opened up across from gate three of Louisville’s Churchill Downs in 1922.

Stepping in, I make eye contact with one of the waitresses behind the fountain counter. She’s about 60, with steel gray hair pulled taught in a slick ponytail, her body hunched over a fresh-out-the-oven honey-glazed ham, which she’s arduously slicing with a cleaver for the morning’s breakfast orders. She advises me to seat myself.

The women of Wagner’s conduct their business over the griddles and the ovens of their kitchen much the same way my four aunts up the Ohio River prepare a Thanksgiving feast, with equal parts sass and sweetness. In this respect, Wagner’s is far from your average diner. In the squeaking booths and across the four-top tables of Wagner’s, local couples share their morning meal and countless blue-haired women gossip. Wagner’s fills with racing fans who come in for breakfast annually before heading to the track. Occasionally, if you’re as lucky as I am, a herd of athletes from the University of Louisville will come in after their morning workouts and the blue-haired ladies will momentarily drop their canards to applaud.

Above the griddles and the ovens hang signs showcasing specialty menu items – ice cream sundaes, short stacks of pancakes, plates of eggs, toast, bacon and, my favorite, a cup of coffee next to a biscuit and a slice of cherry pie. The signs are hand-painted on circular cuts of whitewashed scrap wood, now yellowing with age. Near the entrance, the youngest of the waitresses, whom I guess is close to 40, forces a yellow cake out of a 9 x 13 x 3 pan by pounding against the non-stick metal with the heel of her wrist. She then places the cake on a cooling rack and slathers it with bright pink buttercream.

The bulk of the morning’s commotion takes place in the yellow fluorescent hum of this first dining room, surrounded by countless portraits of prize-winning horses. Walking up a ramped pathway leads to a second space with several family-style tables. It’s here where the pharmacy portion of Wagner’s resides, with shelves stacked with commemorative derby glasses, postcards, Wagner’s T-shirts and their “world famous” horse liniment, which is sold by the gallon. The folks from the track — trainers, exercise jockeys and the like — commiserate and discuss the morning’s workouts here underneath the framed jockey’s silks and continued placards. At the register I buy a handful of postcards and a coffee mug.

The jovial woman behind the counter gets to the mug last and holds it in the air in front of me, “Did you see the one that says ‘Talk Derby To Me?’ I just think that’s so funny.”

Places like Wagner’s, where the regular folks of horse racing gather to talk away from the track, are fewer and farther between these days.

When the first North American track opened in 1665, our equine friends occupied a precious territory between utility and pet, and taking the horse to the track was a testament to the bond between man and horse. The horse wouldn’t be there without the team that groomed him for it, the trainer, the jockey, the grooms, the veterinarians and the exercise riders, and without the horse the team would never experience the exaltation of seeing the beast fulfill its vocation the best of its ability – run.

In horse country, Lexington and Louisville especially, horses are still held in highest esteem. But those of us removed from the sport, the oldest our country has, are left estranged.

When the races do occupy the headlines, the stories most often revolve around animal cruelty or the pageantry around the races, with a story of the occasional champion horse peppered in now and then. We don’t hear about the 4.6 million people whose whole lives revolve around the track. Living and working at the races, these are folks who bear the brunt of the atrocities that have taken place increasingly over the years, and are daily faced with the difficulties of making a living within an increasingly anachronistic sport.

These working people are the denizens of what they refer to as “the backside” — everything that happens in the background apart from the more glamorous world of the grandstand. And all of them — at least the ones I talked to in visits spread across four weeks — want to right the wrongs in their sport.

I overheard the best explanation for their desire in an office on the backside of Lexington’s historic Keeneland racetrack: “One of the biggest things you’ll find about the main people that do many different jobs at the race track – they all love horses. That’s just all there is to it. They all like horses.”

Whether you're the manager of the staging barn, a groom or a stablehand, the horse always comes first.

Travis Durr never planned to be a horse trainer.

It’s five weeks to Derby day, just after sunrise in St. Matthews, S.C., and through an endless stretch of dewy, soon-to-bloom lupin fields, Travis and the team — all of whom work for the renowned trainer Webb Carroll — are going through their morning warm-ups. The lush 61-acre South Carolina training grounds are where countless thoroughbreds have made the awkward transition from yearlings to runners. Though Carroll himself won’t be in until later, it’s clear that teaching is his vocation; not only has he trained innumerable winner’s circle horses through the years, including Goldencents, War Emblem and Shackleford, but he’s taught the bulk of his exercise jockeys to ride, and some of them have graduated to the track.

This morning, eight riders and horses at a time are taking to the track.

“It’s important to get them as close to the actual track as possible,” Durr explains. In the prep barn, he goes through final checks with each horse and helps each jockey to the saddle. “We were just finishing yesterday’s routine when the rain came, so the track’s a bit too soft today; they won’t be running much.” Just off the break of the first turn, from a six-foot platform constructed for the singular purpose of observing morning workouts, Travis overlooks as the exercise riders and their horsemen make their way around the track, coaching them along and keeping an eye out for anything out of the ordinary. “A lot of these horses will be making their way down to the Two-Year Sales in Florida next week. We’re just making sure they’re ready to go.”

Durr and Carroll aren’t the kind of trainers you’ll find in the winner’s circle, though their work with the horses as they develop is critical. They don’t seem to mind staying out of the limelight.

“I grew up with my family raising quarter horses,” Durr says. “I had another job but once I came here I worked full-time. Adolfo here’s been here for 24 years. I’ve been here for seven. This is a big family affair around here.”

Fellow Assistant Trainer Adolfo’s stocky frame seems peculiar atop his lean blonde thoroughbred. His unending smile sports a single shining gold canine tooth, and he’s got crow’s feet so deep they’ve got their own tan lines. Adolfo started out as a groom and worked his way up to exercise jockey before a horse kicked him and shattered his knee – but rather give up on the sport entirely, he chose to stay on with Carroll as an assistant trainer. Carroll, too, has had his own share of scrapes. In ’97 he broke both of his legs in A dust-up that reportedly involved a wagon and a spooked Belgian draft horse, but he came back to training as soon as he was mended up. It seems no incident will shake the men of Webb Carroll’s stables.

The morning’s laps have wrapped by 8:30 a.m.; some of the horses are taken to the trolley — kind of a merry-go-round with real horses — to cool down, while others are simply hosed. The exercise jockeys unload the feed that arrived that morning. It will take the eight men at least an hour to finish the job: The feed for the 150 horses on Webb Carroll’s grounds arrives in 18-wheelers. Tomorrow, Sunday, is the only day off from training. Instead the team will let the horses loose from their paddock stables to wander within the fenced grounds and “give ’em a chance to just be horses,” as Durr says.

Travis guides me around the facility’s endless verdant grounds, taking special care to introduce me to especially noteworthy horses, as well as the fellow employees dishing out feed and cleaning the stalls. “We make sure to give each horse the same amount of attention here – it don’t matter if it’s a $5,000 horse or a $50,000 horse. We’ve got faith in ‘em all.”

Some of the team from the Webb Carroll Training Center during the morning warm-ups. At bottom, Adolfo leads the team to barn after their laps.

With the commotion of a stakes-race day afoot, it’s hard to tell left from right on Keeneland’s grounds.

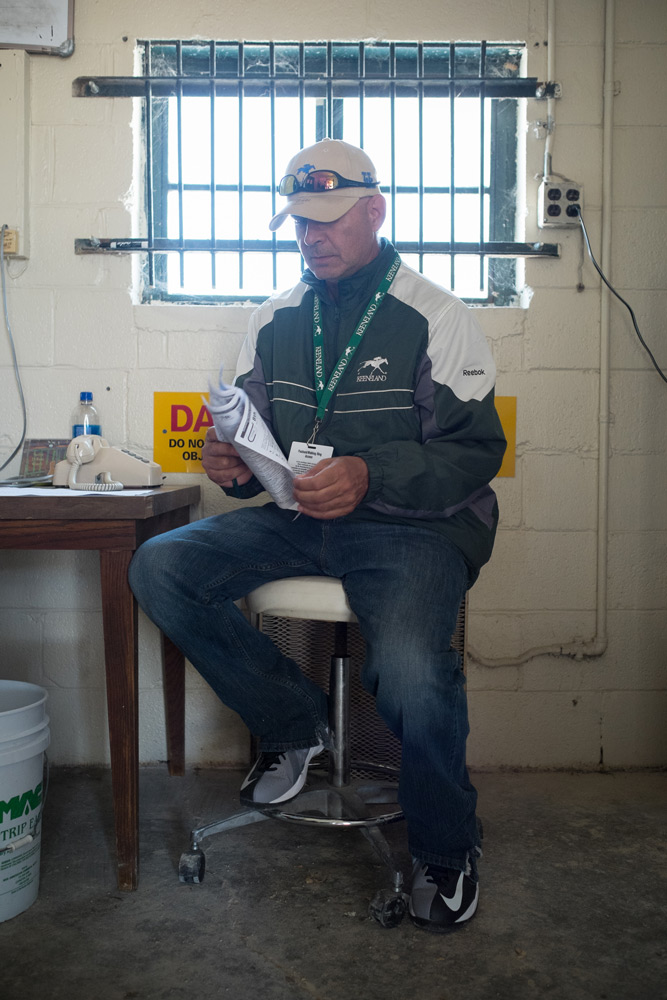

When I say I’m looking for the backside, our green-blazered Keeneland consultant points to a man in a white-and-blue windbreaker hurriedly weaving his way through the crowd with an explosion of brightly colored jerseys in his grip. “Follow Mike, he’ll show you around.” Mike turns his head toward me but doesn’t skip a beat, “How’s it going? You can follow me.” I hustle in his shadow, the Kentucky sky endlessly blue above us, a breeze carrying through the bluegrass. “You picked a good day to be here.” We follow him through the winner’s circle and give a nod to another group of green blazered gentlemen sitting in the shade of a paddock by the backside gate. “Hey Leroy. Hey Trace.” I nod in acknowledgement. Mike halts. “These are our blacksmiths. If something goes awry with a shoe over here, they’re just the guys to fix it.” Leroy and Trace, who collectively represent at least 47 years at Keeneland (Trace has lost count and can only offer up an estimate), humbly wave him off, and Mike smoothly sidesteps his way between the backside gate and the wall of the winner’s circle.

Mike rue

Mike Rue has worked on Keeneland’s grounds since he was 16 years old.

“I basically started out walking hots here,” he tells us, referring to the single lowest position in the business: walking horses to cool them down after workouts. “Just kinda born and raised into it.” He has a few cousins who also work in the industry, but it’s clear from the jovial way he conducts himself that just about everyone feels like kin.

“This position opened up after the Eight Belles tragedy at the Derby a few years back,” he tells us as he sorts through the jerseys. Mike's job on race day is to make sure the right horse makes it to the right gate, and a big part of that is making sure grooms who guide the horses sport the right colors. Eight Belles was a racing filly who held great promise, having made history by winning the ’08 Martha Washington Stakes and being one of only 39 fillies in history to compete in the renowned Kentucky Derby. But that Derby day, shortly after placing second to Big Brown at Churchill Downs, she collapsed at the end of the track with compound fractures in both of her front ankles. She was euthanized on the track, in front of the crowd.

Within a matter of minutes Mike has taken us to the Pre-Staging Barn Office, introduced us to his coworkers, Dan and Adam, along with conducting his business of hanging the appropriate jersey for each horse’s groomsman at their stall, helping conduct final checks. Meanwhile, a veterinarian administers random blood tests.

“They don’t know who we’re gonna get or when we’re gonna get it. Gotta keep them on their toes, you know what I’m saying?” Mike says “Because if they know that we’re testing they won’t use a certain drug or something, but if they know that we’re not testing they may try to sneak one in.”

Fifty yards away an array of owners, trainers and press wait in various attitudes. Even they aren’t allowed in the barn areas with Mike and the others; in this instance, I’m an exception. Outside the staging barn, some trainers stand at attention as close to the gate as possible; a group of seersuckered gentlemen and florally frocked women make small talk under the shade of a sycamore tree; others stand detached and tall in bespoke suits, passively thumbing through their phones.

All the while Mike, Dan, Adam and the remainder of their eight-person staff make sure the horses are ready for the track.

“I’ve got two loves in my life: horses and soccer,” Kostas Hatzikoutelis tells me. “My wife doesn’t seem to mind.”

Much of my interactions with Kostas follow in this suit, truths guised in jokes. Our first meeting takes place just as he wraps up coaching soccer in Sandy Springs, Ga.: He’s still in his training shoes. Kostas and his good friend Jim Culver make up the Executive Team of Dream Team Racing Stable, which they founded together 10 years ago.

“I always wanted to be on the owner’s side,” Kostas says. “It seemed like more fun.” Dream Team’s claim to fame was its partial ownership of Mucho Macho Man, who went on to win the 2013 Breeders Cup Classic.

“These animals are different than any other athlete,” he says. Horses require “the best environment and the most care for them to succeed. And then you get to see something special.” He excitedly tells me about Chief of State, one of Dream Team’s horses, who was scheduled to race in New York later that afternoon. That evening, I get an email from Kostas with a link to the webcast of the race. “Remember that horse I told you was not going to do well that we had running today? Go check the replay…”

Despite the odds stacked against him, Chief of State came in third.

At R&M Racing Stables, the recuperating thoroughbreds are pampered: a foot of fresh straw bedding, warm blankets and plenty of good clean air.

Few athletes make it through entire careers without injury, and horse racing is no exception.

It’s late in the morning in Lexington, and we’re trailing behind Kostas and his partner Jim to visit Hoosier Spirit at R&M Racing Stables’ training center. Becky Maker, a trainer who specializes in convalescing racehorses with minor injuries, and her 12-year-old son, Jake, greet us at the barn. There’s a chill in the air even in the sunlight, and Becky is bundled in a black coat embroidered with the stable’s name. Jake regales us with stories of his competitive football team as we mosey toward the barn to see the horse.

“He tends to get excited,” she indicates we should stand back from inside the stable. “I’ll hand-walk him.”

She and her assistant, Ronald, lead Hoosier Spirit out of the stable slowly. From afar the horse seems regal as can be, standing tall and lean in the Kentucky sunlight, but it’s clear once we’re close that the only thing he’s basking in is the attention.

becky Maker and her son jake at R&M racing stables

“He’s been a bit of a ham ever since we’ve had him.” Kostas says, looking him over carefully. Hoosier was performing well in his races and warm-ups until one morning when he came up a little lame. After a surface tendon tear showed up on his MRI, his trainer, Dallas Stewart, recommended sending him to Becky, who specializes in rehabilitating and retraining horses with minor injuries.

“We did a slight blister on him,” she explained, referring to a rather common procedure amongst racehorses, in which a hot needle is applied to a splint to help stimulate growth, in turn helping it heal faster. She guides the horse to move so Jim and Kostas can see. “It flattened out real nice. It seemed like it was more of the tendon sheath than underneath, which is good.” Becky talks us through Hoosier Spirit’s hand-walking regimen, which is conducted by her assistant Ronald every day in the arena. The arena, the barn and the trolley track make up the extent of the facilities.

“It’s big enough,” Becky says.

After Jim and Kostas snap a bevy of photos, Ronald guides Hoosier Spirit back to his stable. Becky and her son amiably walk us to our cars to see us off, waving goodbye as we pull off of the gravel drive.

Hoosier Spirit and Ronald at R&M Racing Stables

A 5-foot-tall woman in a security guard’s uniform stands on the gravel path amid the owners and the trainers at Keeneland. Mike introduces her to us as Miss Erin.

“I’ve worked here for seven years now,” she says. “I retired; it’s a fun job, a little extra money. My sister works here too. She works security at the tunnel.” She stands with her hands on her hips, eyes keenly scanning the grounds. “The most important thing I do is when the horses go up to the track from the paddock, I call them up and then we all – myself and other security guards – we all keep an eye on them so people don’t get hurt. The horses are so freely accessible, and people don’t respect how skittish they are. And they’re very powerful animals.”

Mike approaches to take us up with him through past the tunnel, beneath the grandstand, to the racetrack. To do this we first make our way back past the congested winner’s circle, where Mike continues to introduce us to strangers. Halfway through he asks me if I’d like to interview Keeneland’s vice president of racing, and next thing I know I’m face to face with Rogers Beasley. The former banker is a stark contrast to Mike when they’re standing side-by-side.

“I worked here in Lexington as a banker for about 15 years, and the higher I moved up at the bank the less I was enjoying it,” he says, and smiles. “So I spoke with some friends who told me to get in at Keeneland. I contacted the track and told them I was a banker and they said, ‘We don’t hire anyone unless they’ve had some backside experience.’ So the next day I put in my two week’s notice with the bank and decided to become a hot walker.”

It was only a matter of time before Rogers Beasley the banker worked his way from escorting post-workout horses into the sales department, and from there he continued his ascent.

“But I’ve never forgotten the backside,” he says. The people in there are the best and the backbone of our business – the hot walker, the groom, the exercise rider – they’re the ones who put the love, the affection, and the 40-60 hours a week into that horse to get him ready to go to the posts for the races, no matter what level. It doesn’t matter what level of horse they are, in the backside they get the same care. They work very, very hard.”

The tunnel underneath the Keeneland track is reserved for the owners, trainers, backside employees and media to reach the inside rail.

About 250 feet in length, it stretches beneath the grandstand. The late afternoon light cascades in on either end of the sweep, giving way to darkness in the center. In that shadow, a stout man with a six-inch top hat and a double breasted green coat, fastened by large brass buttons, is leaning against the base of the arc, scrolling through his phone. I decide to catch up with Mike later. It’s been two years since I last saw him play the “The Call To Post” at Churchill Downs, but the bugler is unmistakable. If you ask Steve Buttleman how he got his start he’ll tell it to you straight.

“Well, I started playing trumpet in the fifth grade and I just stuck with it,” Buttleman says. “I never thought it would land me here.” He looks out through the tunnel at the spectators at the track. Though it’s only his second year playing at Keeneland, he’s performed “The Call To Post” for 20 Kentucky Derbies and Kentucky Oaks. “They had an open call, lined up 20 of us and then whittled it down to two, one of which was me.” He smiles nervously. “Then we had a play-off, and I don’t know what I did but they chose me.” He goes on to speculate at the decision, reasoning that it may have had less to do with His musicianship and more to do with the fact that he had a wife and children and would likely be around for a good long while.

Stepping onto the seemingly sacred dirt track transforms Buttleman. His shoulders, once hunched in repose against the tunnel wall, stand tall and straighten. It’s time for the ninth race of the day, the Jenny Wiley. Steve leans back, trumpet set high against his lips and shining against the late afternoon sun. It’s Steve alone that marks the beginning of the race, note by note. He navigates harmonics and handles tripling with finesse.

Once he’s finished he ambles back up to the railing, assumes his normal posture, and pulls out his phone from his pocket.

Mr. Steve Buttleman, bugler-at-large

The office of Adena Springs, a high-dollar horse-breeding facility, is quite a sight to behold. The facade is decadent as hell, complete with resplendent Corinthian pillars a few stories high. Kostas, Jim and Cormac Breathnach are waiting in the front foyer, which is all recessed lighting and marble countertops. Cormac, quiet and unassuming, picks up his young daughter from her hiding spot behind his leg and leads us to the back of the office. A set of French doors separates this facade from the heart of the stallion barn.

Cormac is an Irishman with a doctorate in veterinary science from the University of Kentucky’s Gluck Equine Research Center where he went on to be the Paul Mellon postdoctoral scholar before pursuing his career in bloodstock. Here the groomers look like they stepped out of a country-club pro shop instead of a farm – well-tailored pants, matching jackets and ballcaps. Next to them and the horses, Cormac stands calmly.

Awesome Again is led out first, a 21-year-old champion 16 hands tall who’s made himself quite a breeding career. “He’s got 14 winners to his name already, most of them on dirt, actually, one of them on synthetic,” Cormac says. “He’s one of the best horses ... ever.” Cormac’s daughter plays with his shirt collar as he speaks.

As Cormac gently puts his daughter down to the ground, Kostas chimes in.

“He’s not so massive or anything,” Kostas says. “He’s just a well-put-together horse.”

Cormac agrees: “That’s not recognized so much in the industry anymore, because (of) the commercial aspects. People are looking more for size, but those aren’t the sound horses.”

When one of Awesome Again’s progeny, Ghostzapper, is led out, Cormac’s point is illustrated perfectly. “You’ll see a lot of this again and again,” he says. “He’s just a little bit bigger, a little more spread, has got a little more sex appeal.” The truth of the matter is we’re standing in front of a legend. Ghostzapper’s progeny, too, are proven – 14 percent of them have gone on to win stakes races. Only one other horse has sired as many winners as him. Simply put, Ghostzapper is one of the industry’s top-ranked sires. “He’s a spectacular stallion is all,” Cormac says. “He’s just pure power. He’s got a real engine. Huge gaskin, amazing depth in the shoulder.”

Mucho Macho Man, who was sold to Adena Springs to sire after his win at the Breeder’s Cup in 2013 , is led out and Jim and Kostas can barely contain their pride. Fidgety and agitated, he’s clearly still adjusting to life off of the track. Jim and Kostas barely take note of this, beaming with pride and joy as they are.

“He walks like he owns this place,” Kostas says. Jim nostalgically recounts how his trainer had difficulty helping hoist the jockeys onto his back, he was so tall. Cormac eggs them on: “You know when a new stallion comes in, it’s not always clockwork that they breed mares or know what to do, how to cooperate. Sometimes they’re just too excited; sometimes they’re just slow and don’t know what to do. He walked in like he was rearing mares all his life.”

Some of the tools of the breeding trade: twitches, a shield for the mare's back in case the stallion is too mouthy and "bedroom slippers"

The decadence continues as Cormac leads us through the stallion barn to overlook the full extent of the Adena Springs property. The farm spans 2,400 acres of verdurous rolling hills, 20 miles of roads and 19 miles of fencing. In the valley, a small community of houses accommodates most of Adena Springs’ employees, who live amid every amenity – volleyball courts, a pool, soccer fields and a basketball court. Also residing on the campus are the farm’s eight champion sires, 150 brood mares and one stocky teaser horse named Tonto. Tonto is kind of an equine fluffer; his sole responsibility is flirting with the brood mares through a window before they’re bred.

“He’s saved a lot of stallions from a lot of kicks,” Cormac says. “He’s a legend in this industry.” Cormac looks at the bulky horse fondly before taking us back into the breeding shed.

Cormac walks us through the less-than romantic nuances of the breeding process – the teaser, the twitches, the “bedroom slippers” that cover the mare’s back hooves – amidst high praise for Mucho Macho Man and his expeditious sexual performance.

“He’s a great one because he comes in, trots down, gets good and ready, gets on the mare and he’s done,” Cormac says. “Like, he’s often through the door and back out the door in two minutes.”

Kostas mutters a “that’s my boy,” under his breath.

Back at Keeneland, I make my way to the railway to stand next to two Hispanic men in colorful bespoke suits. I recognize them from the Pre-Staging Barn. They walked in alongside No. 4, Ball Dancing.

Kostas had told me that the rail was the best spot to watch the race, “even though you may not have as good of a vantage point – it’s the closest to the sport.” He’s right – even when the horses are on the opposite side of the track, I can feel the rumbling hooves in my chest. The two men next to me stand calmly, speaking to each other in Spanish, but at some point I stop hearing them – Ball Dancing and Filimbi are coming up from behind and out of nowhere, overtaking Eden Prairie and Hard Not To Like. The gentlemen’s voices next to me crescendo; they clap ardently. Ball Dancing breaks through and takes the lead. They’re stomping their feet and yelling now, and the rush of the race has swept up the railside. It’s not long after the horses peal past us when the race is called – Ball Dancing by 2½ lengths.

The two men gather themselves and regain their original statuesque demeanor, as some folks from the track roll out a carpet for the owners to cross over the dirt of the track. They make their way across to the turf and I’m by myself at the rail, heart hammering.

It’s six o’clock the following morning, and Keeneland is stirring in the predawn.

Groomers quietly lead the somber horses through the grass, or hose them down post-workout, steam billowing off of their hardened athletic frames into the crisp morning air. A hushed procession of exercise jockeys, thoroughbreds, lead ponies and trainers meander toward the track.

Though the stands are empty, Keeneland feels far from vacant. At the rails the horsemen exchange morning pleasantries, offering congratulations and praises for races well run. At one point Chad Brown, Ball Dancing’s trainer, passes by the Race Commission’s office alongside the track. Another trainer offers him kudos on yesterday’s win. Humble as ever, Chad retorts, “Congrats to you, that was a hell of a race you put on,” before making his way through the gate to the stands.

A lead pony noses toward me curiously, and his rider remarks, “He just wants candy!” We laugh. A French jockey whistles a playful tune when conversation falls quiet. All the while, the horses breeze by, their long strides accumulating confidence which each pounding step. Eventually the pink light of sunrise fades and an hour break from the track is announced.

I think about Travis, Becky, Kostas, Cormac and Mike and how their varied existences all revolve around this – these horses, this track. Leaning against the rail and reveling in the fabled imagery of the morning, it dawns on me: There’s not a seersucker or frock to be seen in this place. There’s not a julep to be found.

The track doesn’t owe a single iota of its heart to the charades we so often associate with it.