You could make the case that Hale County, Ala., is one of the most famous places on Earth that no one has ever heard of.

On the west-central side of the state, south of Tuscaloosa, it was where the world got its lasting images of the Depression-era deep South, courtesy of James Agee and Walker Evans’s seminal 1941 book “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.” Beginning in the ’60s, the county’s rusty, undying warehouses and weather-beaten shacks were repeatedly stamped onto our cultural consciousness as the favorite subject of the photographer and Hale County native William Christenberry.

And that was all before the Mississippi-based architect Samuel “Sambo” Mockbee arrived in Hale County with a grand plan.

Mockbee came in 1993 to help start the Rural Studio, a design-build program that is part of the Auburn University School of Architecture. He believed that the role of an architect includes a certain social obligation, and so he created the Studio as an experiment to get students out of the classroom and put them to work where he thought they could do some good – smack dab in the center of one of the poorest counties in one of the poorest states in the country.

Turns out Mockbee was on to something. Two decades on, the Rural Studio has been wildly successful, piling up awards and drawing attention from all over the globe. Now headquartered in the rambling, Queen Anne-style Morrisette House in Newbern (population 181) in southern Hale County, its 100-plus projects fan out all across Alabama’s Black Belt, reaching over into Perry County and down through parts of Marengo and Dallas counties. More than 800 students have taken part in the Studio over the years, designing and then constructing everything from private homes to a fire station to a skate park. Now divided into Third Year, Thesis and Outreach groups – the latter consisting of those from outside the university – they’ve resurrected churches, experimented with models of affordable yet livable housing and resuscitated parkland that had given over to a swamp.

Tragically, Mockbee died of leukemia in 2001, just as the Rural Studio was really picking up momentum. The job of guiding the Studio fell to a British-born professor named Andrew Freear, who had arrived just the year before. Freear didn’t flinch and got busy expanding the Studio’s reach while sticking to the ideals that Mockbee first laid out.

This year, as the Rural Studio celebrates its 20th anniversary, it’s looking back over the path it has cut through west Alabama. And while most folks still haven’t heard of the Studio’s beloved home of Hale County, it’s a place that now more than ever has one hell of a story to tell.

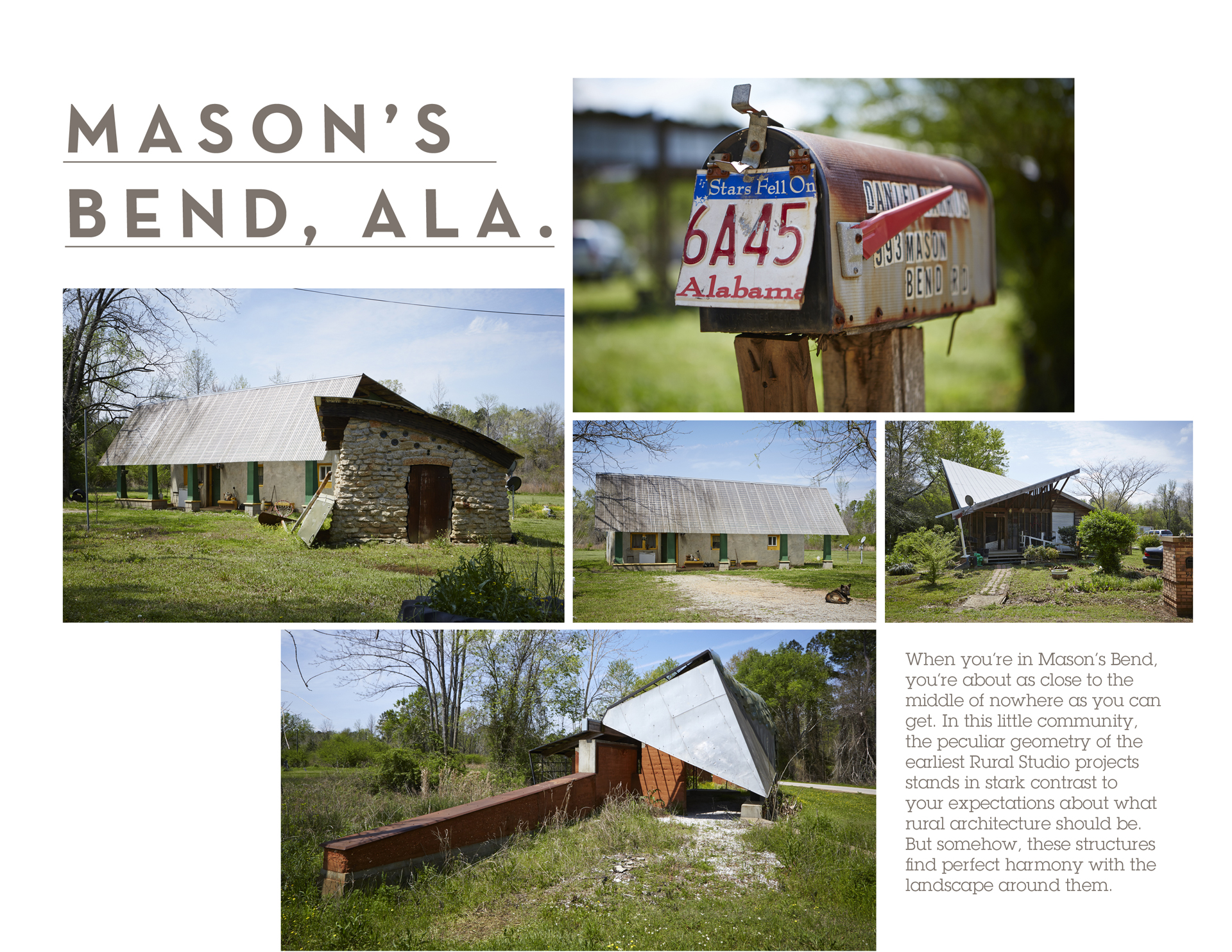

Mockbee, a kind of Southern sage with the face of a sheepdog and the body of a bear, was known to speak in proverbs, one of his most famous and enduring being, “Everyone, rich or poor, deserves a shelter for the soul.” Crisscrossing the South in a beat-up Daihatsu, he saw plenty of people struggling to make do, but the tiny community of Mason’s Bend stuck out. Tucked into a wide oxbow of the Black Warrior River on the western end of Hale County, Mason’s Bend is an isolated cluster of homes occupied by multiple generations of four families. It’s the kind of place that, for all intents and purposes, has no business even existing anymore. But Mason’s Bend is home for the Harris, Bryant, Green and Fields families, and it’s a sacred place for the Rural Studio as well.

Four of the first five projects the Studio took on were in little Mason’s Bend. Those include a cobblestone smokehouse and a home made of stucco-covered hay bales for the Bryants, as well as the Butterfly House, whose roof resembles fluttering wings, for the Harrises. The most well-known project there has to be the famed Glass Chapel community center. Its name comes from the quilt of car windshields that forms part of the small building’s roof. The windshields were salvaged from a Chicago junkyard by one of the students who worked on it back in 2000. Sadly, the building has seen better days: Chunks of its rammed-earth walls have crumbled away, and graffiti covers parts of its interior. Still, the power of the structure remains intact.

Because, by law, Auburn cannot subsidize construction, the Studio receives operating funds from the university but must rely on donations to fund the projects. That means design decisions often hinge on what materials are available. Hence the car windshields in the chapel and the odd materials in other early projects like the Yancey Tire Chapel and the Corrugated Cardboard Pod, part of the student dorms at the headquarters in Newbern. Under Freear, the Studio has moved somewhat away from using the kinds of non-traditional materials that were common during Mockbee’s time, instead favoring more solid, long-lasting components like steel and reusing parts of buildings whenever possible.

“You’ve got to be more grown up,” Freear says, “and be sure how long buildings are going to last.”

As the Studio has expanded, so has its ambition. Now, instead of doing things like building houses out of carpet tiles, they take on public-use projects like parks and Boys & Girls Clubs, the sort of work that can lift up entire communities.

In Newbern, down the street from the Studio’s mini-campus, you’ll find the slender, cathedral-like Fire Station, which was the first public building constructed in town in the last century. Next door is the new Town Hall, a much-needed civic space for the hanging-on-by-a-thread town. And nearby is the newest addition to Newbern’s recent building boom, the Public Library, now under construction in a long-vacant bank building.

In Greensboro, the county seat and self-described “Catfish Capital of Alabama” nine miles north of Newbern, the Studio has left its fingerprints practically everywhere you look, from the modern, hangar-like Animal Shelter to the Hale County Hospital Courtyard, where tooth-white walls are formed from misprinted headstones, to Lions Park, now chock-full of Studio projects including baseball fields, a skate park, a playscape straight out of Super Mario Bros. that’s made from old mint-oil drums, and a shiny steel concession stand that opens like a massive mouth to reveal its counter.

When the students do think about building houses these days, they show off the kind of raw, moonshot zeal that tends to wear away by the time most of us turn 30. They ask big questions like, “Why does anybody have to live in a trailer?” As in all rural areas, trailers are everywhere in Hale County. They’re “faceless and inhuman,” Freear says. They don’t appreciate in value, and they don’t last.

The answer to that big question is what the Rural Studio calls the 20K House, a livable home designed simply and efficiently enough to be built on a large scale by contractors for just $20,000, roughly the amount a person on Social Security can receive through the Department of Agriculture Rural Housing Service’s Direct Loan program. “Since 2006 we’ve been looking at the 20K House,” Freear says, “which has no design value in it at all. No architect, no builder, no contractor, no developer could afford to do that. And yet we have this sort of luxury of a constant supply of students, an endless supply of folks who could live in them, and so we can watch. I almost feel more of a responsibility to do it.”

The houses are small and modestly designed, especially when compared to the now iconic, rather idiosyncratic homes in Mason’s Bend. But they’ve been worked over meticulously, with a nod to another iconic style of home that you’ll still find all over Greensboro. “All of our 20K Houses ... to me what’s interesting about those is that the architecture of those houses is learned from antebellum houses that were built 150 years ago,” Freear says. “They were all wooden houses. They were all raised off the ground. They all had big roofs and big overhangs. They all had tall ceilings. They all had good cross-ventilation. They all had porches. And they survived, right?

“Forget the times that they were built in and all of the kind of social, cultural, political shit that happened, they did something right with their accommodation. They were smart and the things have lasted, so why not learn from those?”

So far the Studio has built 12 20K Houses in all. This year, as part of the anniversary, they’ve raised money to build eight more. Each one takes about three weeks to complete.

“At schools of architecture, very often I wonder why people aren’t more interested in housing,” Freear says. “And housing as a kind of an aggregation. Because it is a challenge, and it’s also difficult. And I think schools of architecture don’t do it because it’s not that sexy. It’s not going to attract students. Tell them we’re going to design a museum and maybe they’ll want to come do it.”

Freear pauses, leaning back in his chair to look at pictures of 20K Houses that cover the walls of his office.

“I’ll go to my grave believing it’s relevant,” he says after a moment.

If all this is making you rethink the way you look at architecture, you’re not alone. Steve Gentry grew up in Demopolis, Ala., just south of Hale County. He moved to Louisiana to work for a number of years but returned when he married a local girl. Wanting to help affect some positive change in the area, he served on the Greensboro City Council from 2008 to 2012, working closely with the Rural Studio on the projects in Lions Park.

“What I’ve learned was this is more than just architecture,” Gentry says. “A whole lot more than architecture. I mean they really got involved with the community, the needs. And I’ve looked at it as them saying ‘What problems can an architect solve in rural America?’ And it was profound to me that they were so much involved in not just building a building but building things that made us better.”

“Architecture is a pretty good education for asking questions about stuff,” Freear notes. “Steve Gentry has been blown away by what we as architects have been able to offer as far as resources. Especially in places like this, there are not great expectations. So we try to raise people’s expectations without patronizing people and patronizing our students.”

These days, Gentry’s passion is the budding Greensboro Farmers Market. While he was on the City Council, he floated the idea of starting a market but wasn’t able to get the city behind him. “So of course you know who I went to,” he says.

Freear, already frustrated by the lack of fresh produce available in the area, jumped at the idea. Rural Studio instructors took the project on themselves, designing mobile stalls that could be towed wherever the market set up. They helped get the word out by going to schools and working with kids to design flyers, and they created a logo and painted it on the side of a building downtown.

This spring will be the start of the market’s fourth year. Situated across the street from the Piggly Wiggly next to the road that connects Greensboro with Newbern, the market has grown every year, Gentry says. When it started, there were only three farmers from Hale County. Last year, 15 local farmers participated at one point or another. “When I was a kid growing up in this part of the country everybody had a garden,” Gentry says. “But that was sort of an art that was getting lost and people were not doing that anymore. Come to find out yes, we can do that and we can make a little money at it, too.”

The Rural Studio has “started to be trusted as a neighbor if you like, and as a resource, and inevitably these sorts of things at the beginning, they sort of flounder around looking for an identity,” Freear says. “I think now it helps to kind of identify resources and offer resources. You know, people who are trying to do stuff, help and support them, that’s it. The Safe House is a classic example.”

Like Gentry, Theresa Burroughs knew just who to talk to when she needed a hand back in 2010. The founder of the Safe House Black History Museum in the Old Depot neighborhood of Greensboro, she had watched the Studio chip away at problems around Hale County for years. Now the museum, which opened in 2002, was desperately in need of a renovation, a shot in the arm to help get its story out, because, really, a story that good needs to be told.

The shotgun shack at the end of Davis Street became known as the Safe House on the night of March 21, 1968, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. came to Greensboro to speak at St. Matthew AME Church. King was in town to rally the rural base that had first set the Civil Rights Movement in motion years before. His appearance drew quite a crowd, of course, and local members of the Ku Klux Klan took notice. Fearing for King’s safety, organizers of the event secretly shuttled him to the nondescript little house, which was owned by the Burroughs family. Theresa Burroughs remembers watching Klansmen ride around in pickup trucks that night wearing their hoods and robes, the lights on inside the trucks’ cabs to make sure everyone could see their shotguns. The Klan never found King that night. But only two weeks later would come the fateful day at the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis.

Burroughs, one of the many local “foot soldiers” in the movement, started organizing protests when she was only 17. “We were just invisible people, so we had to do something,” she says in a short film that plays in the museum. Looking into her eyes as she tells story after story, you see history staring back at you. Burroughs was arrested in Montgomery during the bus boycott. She was beaten on the Edmund Pettus Bridge during “Bloody Sunday,” the first Selma to Montgomery march.

The Safe House Museum is her legacy, but it’s too often overlooked, she says. “I remember some young man was walking by one day and he said, ‘You mean to tell me that Martin Luther King stayed right in there in that green house?’ He said, ‘Yeah right. You think Martin Luther King would come to Greensboro, some little place like Greensboro?’

“It makes me feel that there’s been a disconnect between my generation and the generation two generations below me that have not continued the struggle, because the struggle goes on. I tell them all the time you can jump on the train and ride or you can just keep walking. It goes on.”

The Rural Studio’s renovation, completed by three thesis students in 2011, restored the house to its original state and connected it to a twin shotgun next door via a glass-walled walkway that is covered in a transparent image of the second Selma to Montgomery March. Recently, the museum took third place in the Building of the Year competition held by American-Architects.com. An event was held there as part of the Studio’s anniversary, drawing a crowd of locals.

“We have the toughest time getting people from the community to come to the museum,” says Dave Cooper, one of the museum’s board members. “But I think that it’s slowly growing. We have to break this community out of the paradigm that they’re in.”

“I think the Rural Studio is one of the better things that have come into Hale County in my lifetime,” Burroughs says. “They talk about food stamps and things like that. But you know, there’s so much empty land out here, we can raise food. We don’t have to have food stamps to eat, you know. Because we can live without those. But to come in and give people comfort, just to have hot and cold running water, that’s changing a person’s lifestyle.”

When Mockbee started the Rural Studio, he made it clear that part of the mission was to help the people of west Alabama. The need is certainly there – according to the latest Census figures, close to 30 percent of Hale County’s 15,000-some-odd residents live below the poverty line. But social work can be a rather heavy, if not controversial, cross for the Rural Studio to bear, and Freear is quick to draw a line between the Studio’s work and charity.

“It’s not meant to be do-gooding,” he says. “I think it’s a response to necessity. At the end of the day we’re a school of architecture, right? I mean these folks are getting classes. And so anything we do is really a byproduct of those classes. I hope it’s a good byproduct.

“We ain’t changing the place,” he continues. “We’re not ambulance chasers, I don’t want to be perceived as an ambulance chaser. You know, architecture is not going to cure poverty, but I think we’ve helped some organizations here that can begin to have an impact on the health and welfare of people here.”

If you want to find a “do-gooder” in Hale County, you don’t have to look hard. Head down Main Street in Greensboro to the office of H.E.R.O. (the Hale Empowerment and Revitalization Organization), a non-profit housing resource center, and see the director, Pam Dorr. A tornado on two legs with a smile that could melt a frozen pipe, Dorr first came to Hale County from San Francisco in 2003 as an Outreach fellow with the Rural Studio. Originally from the San Francisco Bay Area, she had worked as a designer for Victoria’s Secret and Baby Gap. A friend gave her a copy of a now well-known book about the Rural Studio by Andrea Oppenheimer-Dean and Timothy Hursley, and that was all it took.

“Sambo Mockbee was doing work that I was doing work on a small scale there” in San Francisco, Dorr says. “I had done some community garden work and helped some homeless people get on disability and try to find ways to live in the most expensive county in California, or most expensive in the nation, right?

“I didn’t know much about architecture and I certainly didn’t know if this would be a fit for me. You know, I wanted to learn more and I didn’t feel challenged in my job, so it was a chance to kind of wake up a little bit.”

Long story short, that was more than 10 years ago, and Dorr never went back to California. “I just stayed,” she says. “I never went and got my stuff. I rented out my house there. It worked out well. You just don’t go home again.”

When Dorr was working with the Rural Studio, she was often asked to do odd jobs for locals, help repair an elderly woman’s home, for instance. But mostly she was asked to research, to investigate what it was that the community needed.

“We were really just looking at federal programs that are supposed to work nationwide, why have they stopped working here?” she says. “What could we do to make those work again? And that’s really the basis of what we still do today, you know, just asking those basic questions. Like, why don’t things work?”

The answer: “It’s a lot of things,” she says. “I think a lot of time federal agencies expect people to be web-based and our culture may not be web-based. So as the programs moved away from local offices to a regional office, it’s unlikely that a local family would travel an hour and a half to get somewhere, and then when they get there they’ve got to go home and get some paperwork. They end up just getting lost in that shuffle. And what I was finding was that 80 to 90 percent of applicants that qualified for programs were getting dropped for non-responsiveness.

“They were waiting three to five years to get help,” Dorr continues. “So if they had a hole in their roof and they wanted help they would wait three to five years to get that help. So our job was to create this pathway or navigate through that.”

H.E.R.O. has no formal relationship to the Rural Studio, but naturally their work overlaps. “Say the Rural Studio went to Mason’s Bend and built a beautiful home. What we can do over the next 20 years is help that family stay in the home. If they need repair we can teach them how,” says Dorr, who was also closely involved in the impetus of the 20K House effort.

You can see the product of Dorr’s efforts all up and down the historic storefronts on Greensboro’s Main Street. First there was the Thrift Store she started. Then came PieLab, a community meeting place disguised as a bakery whose motto is “pie + conversation = social change.” Next up was HeroBike, which has been clearing swaths of bamboo from around the area and turning it into bicycles. The businesses make jobs in addition to pies and bikes, of course, and they have pointed a pretty bright spotlight on Greensboro – HeroBike was featured on the CBS Evening News recently, and PieLab was nominated for a James Beard Award for best restaurant design in 2010.

The snowball that Mockbee kicked off a mountain two decades ago now looks to be barreling through downtown Greensboro, and that has attracted a lot of folks in the design world to come to west Alabama. Project M, which helped create PieLab, is probably the most well-known of the visiting programs. Started by the designer John Bielenberg, Project M – the “M” is for Mockbee – has worked often in Hale County over the past decade, raising funds to hook houses up to the municipal water system, for instance. Recently, a group of designers from the University of Kansas were in town building bamboo skateboards at the HeroBike shop.

For Freear, ever the uneasy provocateur, the scene in Greensboro can raise some concerns. “We certainly don’t want to be like Marfa, Texas, where the artists have overrun the place. This is Newbern, Hale County, west Alabama,” Freear says.

“I’m glad I’m not in Greensboro. I’m worried that it’s sort of understood as being part of our legacy. And unfortunately every young person in Greensboro is understood to be a Rural Studio student and actually they’re not. And they’re certainly not under the same leash that they are with me. Read into that what you may. There’s nothing I can do about that, and I’m not interested in policing other organizations.

“Not about us,” Freear says, his voice rising slightly. “Not about us. Not about our kids feeling good about themselves. It’s not about happy, feeling good. It’s about doing the right fucking thing.”

The Rural Studio has entered its third decade at a full sprint. Thanks to a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Studio has commissioned a short film on its work. A third book in the critically lauded series by Andrew Oppenheimer-Dean and Timothy Hursley is on the way. And a number of events, like alumni lectures, have been taking place throughout the school year.

The Newbern Library, Greensboro Boys & Girls Club and a Boy Scout Hut in Lions Park are all expected to be completed during this anniversary year, along with the new 20K Houses. The Rural Studio Farm, a long-planned attempt by the Studio to become more sustainable by sourcing its own food, is set to officially open soon at the campus in Newbern.

It seems like another one of Mockbee’s well-known sayings – “proceed and be bold” – is on everyone’s mind these days. But still, Freear isn’t ready to pat the Studio on the back. “Twenty years is not a long time,” Freear says, “but it probably gets difficult from now on, because a lot of it is about responsibility. And responsibility is not necessarily very sexy, for students or for anybody.”

You would never hear it from Freear, but it sure looks like Hale County has finally found its success story.