Where do you go when you need to hear the voices of lost loved ones? A hundred years ago, if you were a Southerner looking for someone to help you talk to the dead, the place to go was Cassadaga, Florida. In 2017, it still is.

Story by Jessica Handler | Photographs by Ansley West Rivers

From The Daytona Daily News, January 1911

Lake Helen: Surrounded by several pretty lakes and guarded by lofty pine trees is Lake Helen, a winter resort of no little importance. Camp Cassadaga, a spiritualistic camp-ground, is situated near Lake Helen and at this place several hundred people make winter headquarters.

Most of my family is dead. I see them all the time, although it’s more accurate to say I feel them. Sometimes I think if I could turn my head quickly enough I’d catch them just behind my shoulders, but I never do. My mother is at my left shoulder, my sister Sarah on my right. Sometimes I hear her laugh.

I’ve come to Cassadaga, Florida, because I want to hear someone tell me that my family is still around me. My mother, my sister Sarah, and my sister Susie, too. My father. Willie the dog, Ed the cat, Peach the cat, and my mother’s mother, my grandma Jo. So many lives ended, so many voices silenced. I want someone to tell me they are still right here, that they love me, and that missing them so much I am sometimes speechless with grief is something I can stop doing.

I am not a religious person, not “spiritual” in any sense. But I have ghosts. And so, I am here. Cassadaga is home to the Southern Cassadaga Spiritualist Camp Meeting Association, a community incorporated in 1894 by a fellow from Pike, New York, named George Colby. Colby was a medium, who, on the advice of his spirit guide, took a train to Jacksonville, Florida, a steamboat down the St. Johns River as far as it went at the time, and then hoofed it 10 or so miles. There, in the flat scrub of central Florida among the longleaf pines, he founded the winter home for the Spiritualist community of Lily Dale, New York, a community organized in 1879, not far from Cassadaga Lake, New York.

Otherworldly practices like séances gained traction after the Civil War. More than 500,000 families on either side of Mason-Dixon Line had at least one son, brother, or father killed. Many of the living wanted to reach out to vanished loved ones, and the practice of Spiritualism, where mediums claimed to transmit messages from the beyond, offered a direct line. The living wanted to say goodbye, or hello. They wanted to stop being speechless with grief.

By the end of the 19th century, if you wanted mediums in the South, you wanted Cassadaga.

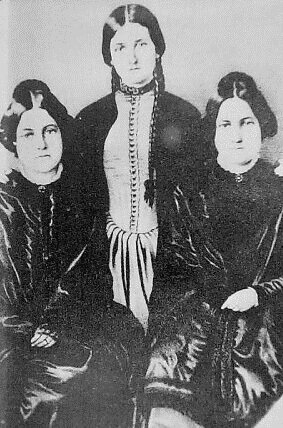

There’s a second reason I’ve come to Cassadaga, and that’s my fascination with a set of sisters other than my own. In 1848, Maggie and Katy Fox intrigued the citizens of their hometown of Hydesville, New York with what they came to call “spirit rapping.” Legend has it the two girls heard a knocking somewhere in their house. Rather than being frightened by the disembodied sounds, they communicated with the noises, asking questions and getting knocky answers in the “one means yes, two mean no” vein. Neighbors came to witness the demonstration and to ask – and have answered – questions of their own.

The Fox Sisters

Maggie and Katy soon grew overwhelmed by the crowds at their home and decamped to their married sister Leah’s house in nearby Rochester. There, the sisters amped up their extreme listening skills and founded the concept of Spiritualism — essentially the idea that life continues after death and that the dead can be contacted in the spirit realm.

Mid-19th century Rochester was a hub of religious and social reform, so much so that the area became known as the “Burned Over District” due to the proliferation of religious movements. Religion and social reform often go hand in hand, and one of the girls’ followers, abolitionist Amy Post, made her home a stop on the Underground Railroad. Susan B. Anthony (not a Spiritualist) lived in Rochester. Frederick Douglass (also not a Spiritualist) published his anti-slavery newspaper, The North Star, from Rochester. Over time, a particular group of Quakers in Rochester called the Waterloo Friends formed a bond with the three Fox sisters, and declared themselves Spiritualists.

And Cassadaga? The Fox Sisters never came to Florida, but George Colby, the fellow whose spirit guide directed him southward, was born in Pike, New York, just down the road from Rochester. The Fox sisters’ childhood home was moved in the early 20th century to Lily Dale, New York, although it has since burned to the ground.

Taking the long view, the Fox sisters are the reason the town of Cassadaga, Florida exists in the form it does. Taking a slightly shorter view, the Fox Sisters are why I have come to Florida, listening for a word from my own sisters.

Orphans Looking for Ghosts

From the DeLand Weekly News, January 23, 1903

Orange City – October 14. George Colby of Cassadaga and L.H. Brooke of Oak Hill drove over from Cassadaga Thursday morning on business.

At this juncture, a glossary may be helpful. From a bright red flyer I picked up at the Cassadaga Welcome Center:

A medium is one whose “organism is sensitive to vibrations from the spirit world.” It’s through them that spirit intelligence conveys messages.

A spiritual healer is not necessarily a medium, and sometimes heals through laying on of hands.

Spiritualism is the “Science, Philosophy, and Religion based on the principle of continuous life.”

A Spiritualist believes in Spiritualism.

A person becomes certified to be a medium or a healer. This isn’t something you decide to do on a whim. Training is involved, and the brochure tells me that multiple levels of study over four to six years are required.

Not from the flyer:

A Spirit guide doesn’t have a body, but as the name suggests, guides a living being.

Clairvoyants see, clairaudients hear, clairsentients feel. One person can do all of these. Or not.

These days, Cassadaga is an unincorporated community in Volusia County, Florida, with a post office, a hotel, and fewer than 100 full-time residents. It’s also recognized on the National Register of Historic Places, which means, among other things, that it “still look[s] much the way it did in the past.” The closest big towns are Sanford and Deland. The closest little town is Lake Helen. Daytona and Orlando aren’t far, at least in a physical sense. In an emotional sense, they are worlds away.

Cassadaga is a quiet sort of tourist destination. The bookstore sells T-shirts with slogans like “Cassadaga: Where Mayberry Meets the Twilight Zone.” Present-day Cassadaga shows up in travel articles about odd American places. It gets mentioned on the ghost-hunting shows. A visitor can take walking tours of the town, or classes in the “Art of Mediumship,” or attend the Gala Days celebration. But it’s mostly a tourism of the interior. Tripadvisor currently gives Cassadaga Spiritualist Camp 85 “excellent” ratings and two “poor” ratings, with the usual range across the middle. Search words include “eye opening” and “peaceful,” along with “historic town” and “lost loved ones.” The phrases “historic town” and “lost loved ones” make my heart sing. I am drawn to places that knock out their stories from inside the walls.

My husband Mickey and I have driven eight hours from our home in Atlanta, which is about the limit of my sitting-still ability. Remnants of Chex Mix and white-cheddar popcorn from a mini-mart (Pepe’s in Tifton? The BP station on I-20 near our house?) will need to be vacuumed from my floor mats and cup holders. I’m eating junk food, but at least I’m drinking herbal tea out of a portable jug. Somewhere south of Valdosta, a billboard advertises a “14-foot gator!” Mickey and I don’t even look at one another before we snicker, in unison, “that’s what she said.” This is the adult version of wanting to stop at every welcome center or playing the license-plate game until someone nods off. We’re pleased by the fresh orange juice at the rest stops, but lament the absence of plastic alligator toys or serrated straws to slam into a whole orange.

How many people take road trips looking for ghosts? I don’t mean overt ghost hunting, but the unavoidable encountering of ghosts in familiar landscapes. At highway speed, I try to catch evidence of lives lived and gone in the collapsing, rusted-out barns, gas stations, and concrete pads that flicker past.

When I travel, I never fail to wonder what the same trip was like before my time. How did a person traverse these mountains, this desert, those plains on horseback, with no one for company but their conveyance animal and the folks who populate their wishes? With all this wide-open landscape, a person would think they could see their future and their past, and watch themselves coming and going all at once.

In the car, Emmylou Harris sings from my iPod, “I am an orphan girl.”

They Are Everywhere

From the Ocala Evening Star [date unknown]

To Lake Helen, Fla. – September 15 and October 15, with limit to return 60 days from date of sale at rate of one fare for the round trip, account of Cassadaga Southern Spiritualists Camp meeting.

My ghosts are everywhere. Waving to the Amtrak Auto Train as it hurtles past us in the town of Barberville, Florida, I see the train as a silver bullet from the past. Throughout my childhood, my paternal grandparents took the Auto Train from Washington, D.C., to their winter place in Sarasota, Florida. My sister Sarah and I flew from Atlanta to visit them, airline-wing pins on our blouses and “stewardesses” tasked with watching over us, but in the Eastern Airlines jet, I loved the idea of the Auto Train below us, a vehicle so capacious, so luxurious, that cars travelled under a power not their own.

Mickey and I find that at Cassadaga, the waitress in the hotel restaurant has the same first name as me. She writes her name in purple crayon on our paper tablecloth, dotting the ‘I’ with a circle. The road out of Deland to Cassadaga is State Road 44, Voorhis Road. Seeing the road sign makes me shriek with a little burst of delight. I’ve been writing a book in which a medium with a grudge is named Mrs. Voorhees.

The Cassadaga Lyceum looks like the dining hall from my summer camp. The pine-paneled walls are hung with old photos and signage from the history of Cassadaga. We are two of a group of six who have signed up for the historic walking tour on a bright December afternoon. Fifteen dollars each.

When our guide mentions the Fox sisters, I don’t hide my delight. “Maggie, Leah, and Katy…” she says, beginning their story, and I nod, saying their names along with her.

Walking Cassadaga’s streets gives me the disorienting feeling that a central New England town from the era of William Howard Taft has landed nearly wholesale among the palms and wax myrtle. This doesn’t mean the place isn’t contemporary — a yellow school bus trundles past on the county road, the vending machine on the Welcome Center porch sells sodas and snacks, and the bookstore takes American Express. But much of the architecture is deliberately reminiscent of New England. This was once a winter home for Northern Spiritualists, after all.

Many of the homes in Cassadaga are clapboard. Some are smallish, but not all. Harmony Hall, two stories high with verandas and a wide central hallway, was built in 1897 as an apartment house. Brigham Hall, built the same year, has a deep porch and tall windows; the exterior is white-painted board. The folks who built it were the Brigham brothers of Fitchburg, Massachusetts, railroad millionaires and Spiritualists. Andrew Jackson Davis Hall, now the Welcome Center, Lyceum, and bookstore, was made in 1905, a long and low-slung building. The town thrived: Cottages and bungalows built almost a generation later sit on deep lots away from the main road, many adjacent to pocket parks. Time and distance run together here. Discarded sheet music, wet from a recent rain, spills from someone’s trash can. On the far side of a chain-link fence, a woman in bedroom slippers scolds her barking dog from her back door.

The Colby Memorial Temple holds my attention the most. It’s big and stucco and not New England at all, with louvered windows and a Mission-revival arch above the heavy front doors. Essentially, it’s cousin to my beloved Works Progress Administration-era elementary school in Atlanta, with the same interior smell of peppermint and old wooden chairs. Sunday services are held here, and “message services,” and some classes.

A Stop in Volusia

From the Deland News, February 12, 1909

New faces are seen at every turn, and rooms in cottages are being filled, but there is still room more guests at the Cassadaga [hotel] and Brigham Hall, and three cottages for rent upon the grounds. Visitors from nearby places have been daily attracted here. … The flags of all nations have a fair showing with “old glory” as a leader.

Cassadaga is quiet like a town in an old movie, quiet like summer childhood, quiet like the moments before sleep. A cluster of women and teenagers, tourists like us, ask me if I know where they can gas up their car. (I don’t – maybe Lake Helen, I suggest, wondering if I look like I belong here, like I know my way around.)

I think of that Twilight Zone episode, “A Stop at Willoughby,” in which a harried executive finds that his commute takes him not home to the suburbs, but to a sun-dappled town on a day in the late 19th century.

The only way to stay in Willoughby is death.

The Cassadaga Spiritualist camp administrative offices are inside a green-roofed, two-story clapboard house at the top of a hill. The building is called Summerland House. Our walking tour doesn’t take us there, so we gaze from the bottom of the hill. Summerland is the Spiritualist term for heaven.

Tom Petty grew up in Gainesville, Florida, about 100 miles from Cassadaga. His song “Cassadaga” interests me less than his hits, but it does have that “Fortune Teller” trope, from the Allen Toussaint song that the Rolling Stones covered, that Alison Krauss and Robert Plant covered, that everyone’s high school friends played in any number of garage bands. The song implies there’s a mysterious woman out there, the object of your desire, who knows you better than you know yourself. When you finally catch her, that mysterious woman points you inward, where you find you’ve been waiting for her all along.

At Cassadaga, the mysterious woman is a medium, although not all mediums are women. To work with a medium at Cassadaga, a visitor can select a name from the changing list on a whiteboard in the bookstore. On the day we’re there, three names are on the board. Mickey and I choose a woman with a soccer-mom name, and read her bio in a three-ring binder on the table. She has years of experience. She’s a former pastor of a Spiritualist congregation.

The way to make an appointment with the medium of your choice is by calling her on a landline. I pick up the handset of what appears to be a Trimline phone from the 1980s. The big square numbers are awkward and unfamiliar. I have to jog my memory: How do I work this? The tug of the phone’s cord feels weirdly heavy in my hand, but the ringtone is clearer than any cellular phone. The irony isn’t lost on me. I am using a nearly forgotten technology to communicate with someone whose purpose is to communicate with people I cannot forget.

I will not give the medium’s name here because I went to her purely to try a reading. I never told her I planned to write about Cassadaga. Her house is small and neat, the front room is a veritable exhibition of Christmas decorations. We meet in her office just off the living room. I want to record our session, but my phone batteries have run down again. They fail consistently at Cassadaga, a phenomenon that I’m told is the work of Spirit, using my phone’s energy. The medium offers me a charger — she has Mac and Android at the ready — and I plug in.

Now that I’m in Cassadaga, weird shit has haunted my dreams. Last night, I dreamed I used a shovel to hold down a cottonmouth snake while I hollered for my husband to come with a rifle and kill it. We do not own a rifle. I have never fired a gun. I do not ask the medium about my dream.

I have, she says, a lot of yellow around me. She’s talking about my aura. Yellow is the color of the mind. I am analytical, authoritative. She tells me about my grandfather (surrounded by friends), about my mother (proud of me), that my mother is with a small child with beautiful eyes. That she cannot hear my sister Sarah, an adult when she died, because I do not need a medium to contact her. That I should listen carefully to someone named Chuck.

That I went through a time when I wasn’t happy.

Silently, I argue. My grandfather was a loner, although he did work in a busy shipyard. All of us choose to remember the children in our lives as having beautiful eyes. Doesn’t everyone go through a time of unhappiness?

I am a dud at emitting what a medium needs to bring me constructive spirit communication. I leave her tidy house. While Mickey is inside getting his reading, I wait on her porch among the Christmas decorations and a basket of Real Simple magazines. There is suddenly no place as nice as this small front porch. I am calmer than I have been in days. The medium has told me my mother had pretty hands. My mother was very pretty in general. I look at my hands, my mother’s moonstone and garnet ring on the first finger of my right hand. My hands look like my father’s. He had nice hands, too. Real Simple shows me how to make polenta, and I think of how my mother tried to instill patience in me, stirring polenta. I still can’t make polenta, but suddenly I am smiling.

And my editor for this essay is named Chuck, a fact the medium would not know.

A Menace in the Air

From the DeLand News, February 26, 1909

There are people here who belong to other churches who aid in our entertainments and show a kindly interest all around.

The South is a divided place. This isn’t news, and it wasn’t news back in the day. Today, though, Mickey and I drive from our pleasant little VRBO in Deland (where, it turns out, my husband’s grandfather briefly considered buying an orange grove) for the 20-mile drive over to Daytona.

I haven’t been in Daytona since 1968, when as a second-grader I accompanied my father to Daytona Beach for a conference. In the lone Polaroid I have from that trip, three palm trees lean from shadow over a wide and nearly empty strip of beach. Two swimming pools are empty, the rows of lounge chairs, the same. The photo caption, in my childish cursive, reads, “Motel at Daytona the Beach from My Railing.” There are three, maybe four cars on the sand, two heading south, one north, another too distant to make out clearly. I remember I was fascinated and horrified that people drove on the beach. What if the sand shifted and they fell in, the physical world devouring their Bonnevilles and Fairlanes?

Today, the sand has shifted. Gun stores alternate with churches. Condos and apartments line the shore like Easter Island heads, sentries obstructing my view of the sea. A sticker in a car window reads “No Life,” in the bony font of the “Salt Life” stickers, and I turn away, anxious. On Speedway Boulevard, a pickup truck idles beside us at a traffic light, machinery and driver eager to bust through to the next light, the next block, the next phase of this life. In the truck’s back window, a handwritten sign reads:

One

Big

Ass

Mistake

America

From the bars just south of Daytona, Bobby Keys’ sax solo from “Can’t You Hear Me Knockin’?” winds out like a fanged snake. There’s a Mad Max menace to the air, or maybe five hours in Cassadaga has peeled back my armor and made me crave interiority. We find a relic of a bagel place and soothe ourselves with comfort food. I find that I miss Cassadaga fiercely, although I have so far spent only one afternoon there. We’re going back this evening, which can’t come soon enough.

While I make my notes, I listen to R.E.M., “The Sidewinder Sleeps Tonite.” Michael Stipe’s voice tumbles through the repeated lyric, “Call me when you try to wake her up.”

Orbwalk Empire

From the Deland Weekly News, January 1, 1903

Mrs. Nellie Morrison came over from Cassadaga Saturday to attend the chicken pillau supper.

We return to Cassadaga to photograph spirits in the dark, or to try. We can do this with our cellular phones, but pocket cameras like Canon Sure Shots turn out to be the equipment of choice. We are told that Spirit (Cassadagans use the word as a singular proper noun) can show up in photographs as translucent balls of light — orbs — or as strips of opacity across the frame.

Or those are lens flares and low light in a digital image.

If my sister Sarah still inhabited a body, she’d be laughing so hard now she’d pee herself. This thought occurs to me as Mickey and I wait in the little park outside the Welcome Center for the tour to start. This is stupid, I think, but I hold out hope that I’ll photograph something that shows me I am not alone. The Lyceum entrance is lit as brightly as if it were skit night at summer camp. Our guide is the same straight shooter I’d spoken to the on phone when I called for permission to write about Cassadaga. I like her: She’s no-nonsense, not woo-woo.

A dozen people are already here; more come in just past the 7:30 start time. Our guide counts our admission fees into a metal cash box and invites us to sit on the couches and wooden chairs arranged around a coffee table. Twenty-two people at $25 each isn’t theme-park money, but it’s tourism money nonetheless. We’re in an orbwalk empire, so to speak. This is the same room where we’d phoned the medium of our choice. The whiteboard has been erased, tomorrow’s date written across the top.

The guide places an EMF meter the size of a pocket flashlight on the table. The lights flicker reliably as the device scours the room for electromagnetic fields. As we set out after her lecture (how to spot orbs and energy plumes, the sample photos on a digital tablet of ghostly images captured on earlier tours) she cheerfully offers to play a mood-setting snippet of Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor from her cell phone. A yellow tomcat named Simba joins us as we promenade down Stevens Street.

My phone is nearly dead again. It was fully charged when I left the car less than an hour earlier, and I haven’t touched the thing once.

It’s a particularly Florida December night. The moon is full, the air soft and sweet. My sweater stays in the car, and in a T-shirt, jeans, and Doc Martens, I walk pretty much the same route as the historic tour. Stevens Street past Harmony Hall and Brigham House, down the hill to the Colby Temple. Outside the Temple, we come to the first “hot spot.” Orbs have been photographed here before, our guide says, near the memorial to George Colby. The 22 of us wander the park, photographing the dark sky, the Colby memorial, the pine trees lit up by flashes from our phones and cameras.

We are, all of us, attempting to photograph desire.

Once, I read a rumor that no birds fly over Cassadaga. This is untrue. During the day, crows barked and cajoled me from nearly every tree. Egrets and ducks settled on Spirit Pond. Overhead, a shorebird flew.

Of a speaker at the Sunday afternoon meeting in January 1909, the Deland News writes: