150 Years After the Fight,

Our Struggles Continue.

One-hundred-fifty years ago next month, some 25,000 ill-fed, ill-dressed men issued from wood and earth fortifications around the perimeter of what is now downtown Atlanta. Their aim was to sneak around the edge of a sizable Federal army and slay them all from behind. The effort entailed a 15-mile march through the dark of night, in the smothering July heat, down dusty paths and through a trackless wilderness.

There's not a whole lot I can say about these people and their quixotic mission that hasn't been said at absurd lengths by a battalion of better writers and better researchers than I. However, I bike past the remnants of those fortifications on my way to work every day. My house is just a mile from no-man's land.

Modern Atlanta sits atop a thick loam of history, but sometimes you can't tell without a bit of digging. Historical markers are a blur glimpsed from the windows of cars. The terrain has been razed and raised until it bears no relation to the hills and valleys over which armies fought. There are but four antebellum houses still in the city, and one of them was carted across town some 40 years ago. The symbol of Atlanta is the Phoenix, rising from its own ashes, but perhaps it ought to be the ostrich, burying its head against recognition of its own past.

For years I've read about that march and spotted the markers fleetingly from car windows. As July loomed, I began to think, "Gee, I've got a good pair of boots. I ate a double-cheeseburger for dinner last night — there's no reason I couldn't make that march myself.”

So on July 21, 2012, the 148th anniversary of the Confederate march that inaugurated the Battle of Atlanta, I did just that.

Hiking is something people usually do in the woods. I enjoy hiking the wilderness of our great nation as much as anyone, I suppose, but there's an appeal to urban hiking I think is systematically overlooked. It's been said that the Civil War was transformative for the United States not least because it was an opportunity for millions of people — soldiers, mainly — to traipse across it and to get a first-hand idea of what it was they collectively possessed. It’s for the same reason I believe everyone should take long walks through American cities.

There's a big difference between viewing a city from a bucket seat and experiencing it on foot. In a car the landscape spools past like a film, accompanied only by the sound of whatever music happens to be bubbling from the stereo, the atmosphere attenuated to its nadir by air conditioning. It's fast, one-dimensional, and — barring a fiery accident — quickly forgotten.

On foot, by contrast, the world inhabits not only the eye, but also the ear and not seldom the nose. It touches the skin and even the tongue, and it does all this at a stately pace. The horizon manifests its mysteries with exquisite leisure, charging the initiate in both time and sweat for the pleasure. Objects rise up, pass, and linger in the distance, giving you plenty of time to observe, to digest, to think. The road trip may be the modern rite of passage, but as is usually the case with technology, for all we gained, something was lost — richness of experience, in this case. Which, after all, is the stuff of life.

With this notion in mind, I packed a bag — a bottle of water, my phone and an external battery to keep it charged, a pair of binoculars, an expensive (borrowed) camera, and a giant hunting knife with which I imagined I would defend the camera if I wound up running afoul of hoodlums. I stepped out of the front door of my house at 12:30 p.m. on Saturday, July 21, with a light heart and a matching step, determined to share some of the experience of that particular group of soldiers on a similar day 148 years prior.

For those who are not regular subscribers to Military History Quarterly, a bird's-eye view of the event is in order.

Throughout the summer of 1864, Federal Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman had relentlessly driven his Confederate foes under Gen. Joseph E. Johnston southeast from Chattanooga to Atlanta, roughly along the route of the modern I-75. Johnston was a wily defender, but Sherman was tenacious, forcing Johnston to retreat time and again, finally reaching Atlanta in early July. The Confederate government took a dim view of this turn of events, and plucked Johnston from his command on the eve of the Battle of Peachtree Creek, replacing him with his very aggressive — some would say rash — subordinate, Gen. John Bell Hood. As he had done in each of the previous battles of the campaign, Sherman sought to circumvent, or "flank," the Rebel defenses, sending half his army, under Gen. James Birdseye McPherson, southeast toward Decatur.

After a failed attack on the Federals as they crossed Peachtree Creek north of Atlanta, Hood drew his troops into the city's inner defensive lines, in the hopes of getting Sherman to stick his neck out. Sherman arguably did just that, sending McPherson due west from the Decatur area along a route roughly corresponding to I-20. At nightfall on July 21, McPherson's 35,000 men were arrayed in a north-south line, from somewhere near the intersection of I-20 and Moreland Avenue to the vicinity of Little Five Points, with a reserve division (around 12,000 men) encamped in modern Candler Park.

Seeing his opportunity, Hood ordered one of his corps commanders, Gen. William J. Hardee, to march his men along a hook-shaped route, south, then east, then back north, seeking to fall undetected upon the left flank and rear of McPherson's army. The march was to be performed under cover of night, aiming to recreate Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson’s similar maneuver at Chancellorsville the year before, which had produced a stunning victory. Audacious as Hood’s idea may have been, however, Hardee’s march was beset with unexpected obstacles, and the troops were not in a position to attack until past noon the following day, by which time McPherson had sniffed out the plan and sent his reserve to meet them. While the Confederates enjoyed some initial success, the offensive ultimately failed, and subsequently the Confederate position in Atlanta began to slowly unravel, culminating in a fiery retreat some six weeks later.

It was Hardee's route I aimed to duplicate.

From left to right: John Bell Hood (C), William J. Hardee (C), James McPherson (U), & William Tecumseh Sherman (U)

Less than two blocks from my house I was waylaid by a thicket of blackberries.

I can’t resist wild blackberries, so I paused to pick as many as I could carry. As I walked along, shoveling blackberries into my gullet, a fact began to dawn on me: Moving 25,000 people through the Georgia countryside was probably a damned difficult thing to do. It’s a good bet the soldiers of Hardee's corps hadn't had a bowl of Kraft macaroni and a roast beef sandwich for lunch. Assuming they had anything at all (not a lock), it was likely hardtack, which is like crackers except harder, like wood. Or parched corn, which has strangely survived into the present day as Corn Nuts, available at most gas stations throughout the land. I like Corn Nuts, but they don't constitute a meal by any standard.

So they were likely hungry. And thirsty — I made my way through half of a 32-ounce bottle of water before I had gone a mile. Moreover, among any group of 25,000 folks, a significant number at any given moment will have to visit the loo. More than a few will stop to shake a stone out of a boot. Or adjust their gear. Or just sit on a rock until yelled at. In short, the column was doubtless disposed to spontaneous dissolution into the woods on either side of the road, and thus the mystery of why it took them so long to cover 15 miles is partly solved.

I ate my berries in solemn silence, thinking how much easier logistics are when you have a credit card.

In 1864, Atlanta was wrapped in concentric rings of fortifications — trenches and breastworks, these latter being essentially mounds of dirt thrown up in front of the former, perhaps with wooden palisades atop them, anchored by earthen forts, or "redoubts," and fronted with “chevaux de frise” — lines of sharpened logs arrayed at angles like crossed swords. The logs provided a formidable barrier to any troops that might make it within spitting distance of the trenches or redoubts.

Not that this was likely; the land for several hundred yards before the fortifications was stripped bare of vegetation to provide killing fields to defenders — several football fields worth of ground any attacker would have to cover with no defense but his own speed and luck.

It was from one or more of these fortifications that Hardee's corps emerged on the evening of July 21. The consensus is that they took what is now Capitol Avenue southward, past Turner Field and on down Hank Aaron Way. I opted to start my journey proper at Grant Park, somewhat to the east of their presumed departure route. Here can be found the only remaining fragments of the fortifications; the remains of a redoubt called Fort Walker, named for Maj. Gen. W.H.T. Walker, one of Hardee's divisional commanders, doomed to die early in the next day's battle while he inspected the land before the Confederate lines. The remains of the fort require some exercise of imagination — they amount to little more than a semi-circular mound of dirt covered in wood chips. In the middle of the circle is a playground, empty and forlorn; this part of the park is partly isolated from the rest by Zoo Atlanta and its parking lot. I threw myself down on the wood chips and took a few pictures, seeking the view through the sights of an imaginary musket.

From here I walked down Atlanta Avenue westward toward Turner Field. This seemed reasonable to me — out of 25,000 soldiers, there had to be a few stationed at or near Fort Walker. I was one of these unlucky fellows, compelled to walk an extra half-mile or so.

The walk from Fort Walker to Turner Field is a microcosm of some of the problems facing Atlanta. Grant Park is an increasingly affluent, gentrified neighborhood. Moving west you pass through an invisible race barrier, from white to black, and slowly through an economic barrier as well, from comfortable to struggling. By the time I reached Hank Aaron Way, I had begun to feel distinctly alien and extremely self-conscious. Like many liberal white Atlantans, I like to think I don't carry any racist baggage, and indeed, among wealthy and middle-class blacks, I find myself much more well-adjusted than I ever did living in places with higher percentages of whites. Like, say, rural Michigan.

But the discomfort that rises like magma when entering a poor black neighborhood is hard to tamp down. I viewed with deep suspicion a group of half a dozen young black men conversing in front of a dingy convenience store — it’s a lizard-brain reaction, and doubtless a deeply unfair one. It was me, after all, that had come into their neighborhood. It’s not as though they were lurking there in hopes that a lone white guy with a pricey camera would come loping past.

It’s a joy to live in the heart of the Civil Rights Movement. I cast my votes for John Lewis with great enthusiasm and I view the MLK Center with great reverence. But that irrational tic is still there nearly eight generations after the Civil War. It’s enough to inspire a deep pessimism, given that there are so many in these parts that seem happily willing to be governed by their passions rather than their reason.

On this gloomy note I turned south, and for a mile or so the caliber of the neighborhood continued to plunge. At first it was mostly residential; tattered cinder-block houses interspersed with the occasional dilapidated market tattooed liberally with "EBT accepted here" signs. There were a handful of churches and mosques, usually in old buildings that still bore the characteristic shapes of the businesses that once inhabited them — fast-food restaurants and banks mostly. There were no functional chain operations of any sort. The few businesses that remained were loners and very much on life support.

As I approached McDonough Boulevard, the character of my surroundings began to take on a decidedly more industrial flavor. McDonough is intertwined with a railroad, and a couple trucking concerns have colonized the intersection between it and Hank Aaron Way, presumably taking loads from the train and sending them across town. There was a cardboard recycling facility as well. These might be bustling on a weekday, but on this day they were as dead and empty as cicada husks.

Incongruously, across the street from the recycling plant was the very posh Carver High School. Carver is no joke. It offers a performing arts program, an early college program that includes some classes at Georgia State University, and a sort of pre-pre-med program. This is in sharp contrast to my own high school, which primarily offered an opportunity for kids to show off their cars in the parking lot. Still I'm surprised at the oddball location of this magnificent school with its lush and lovely campus. Catering to the disadvantaged I can understand, but its placement in the midst of an industrial slum imparts the sense of a besieged castle. It’s hard to fathom how the students must feel here — whether they look inside at the plenty they’ve been given, or whether they look outward at the ruin that surrounds them.

Defunct businesses have a sort of patron saint on McDonough Boulevard — a vast, decaying distribution center that looks to have been extinct for several years. The grounds comprise something in the neighborhood of 20 acres — a sprawling field of broken concrete with weeds sprouting through every available crack and hulking enigmas of yellow-painted steel equipment scattered like dinosaur bones in an ancient riverbed. The main building is the size of two Super Walmarts plugged together, and is tattooed with graffiti tags the size of freeway billboards. A sign indicates the facility's availability to any who might see in its ghostly wreck some vision of an industrious future. I can't imagine many do. And like a punchline, the derelict facility is immediately followed by the grounds of the federal prison.

The United States Penitentiary on McDonough possesses at once an austere beauty and a cold menace. Built in 1902 on a design by the architectural firm Eames and Young, which also produced the design for Leavenworth Penitentiary and many other historic buildings of a less penal nature, the main building is essentially a perfectly squared block of stone the size of an aircraft carrier. It's built out of blocks of granite brought in from a local quarry, which create strong horizontal lines like children's writing paper. The walls are pierced in a regimented fashion with tall rectangular windows, producing a look reminiscent of marching columns. At each corner of the building is a square tower with a smallish onion dome. Top center is a copper cupola.

For all the suggestions of prison bars inherent in the structure, it's not until you take a closer look that it really begins to take on a more sinister character. Every surface upon which a would-be escapee might climb is lined with coils of razor wire. The tall windows turn out to be fakes — they are really just rectangular depressions in the building's face. Within their back surfaces, there are small horizontal windows cut, but these are covered with steel bars. Extending from the back corners of the building is a concrete wall, 38 feet high and four feet thick. This wall runs in a T-shaped circuit four-fifths of a mile long, punctuated at each corner with tall watchtowers that look like something intended for air-traffic control. I tried to spot guards in these towers, but they were invisible behind the bluish glass.

The prison has hosted a good share of famous prisoners: mobsters such as Al Capone, John Gotti, New England crime boss Whitey Bulger, and Jimmy Burke — the inspiration for Jimmy Conway in “Goodfellas”; Frank Abagnale, who was immortalized in the film “Catch Me If You Can”; perennial Socialist candidate for president Eugene V. Debs; Carlo Ponzi and his criminal disciple Bernard Madoff; and no fewer than two former Major League Baseball players, including Denny McLain — the last pitcher to win 30 games in a season. It was also the site of the longest prison takeover in American history, when a group of Cuban refugees being held there rioted for 11 days in 1987.

I stopped out front and took a good number of photos, fully expecting an armed guard to walk over and start questioning me at any moment. The guard failed to materialize, but the rain did, so I trekked across the street to a Chevron, the first business I'd seen for almost two hours that didn't appear to be on the verge of bankruptcy. There was a small Mexican grocery across the street doing a fairly brisk business, alongside a Mrs. Winner’s Chicken and Biscuits that was decidedly not. In the Chevron I pulled 40 bucks out of the ATM and purchased a Coke and the only object I could find that resembled actual food: a "Firecracker," described on the display box as "The Official Red Hot Pickled Sausage." It tasted like a condom stuffed with soil and Sriracha, but it felt proper to eat something official while standing near a penitentiary.

The rain passed quickly, and I hit the road again right away.

The next stretch of the hike, from the prison to Moreland Avenue, was the worst in terms of poverty and desolation. I had slowly come to grips with the looming sense of danger, though I had my moments. At one point I was walking past a small cluster of dingy apartments when a guy on a cell phone fell in behind me. I could hear him talking away loudly and coarsely about a woman. He was totally engrossed, but I still didn’t like having him behind me. Presently, we passed a stretch of road bordered on one side by nothing short of a bona fide forest — oaks and maples with a thick undergrowth of kudzu — and on the other side by an empty field of high grass, across which at a distance of maybe a mile could be seen a few shabby houses huddled together like cowering animals. On neither side was the vegetation less than four feet high, and yet behind the curtain of grass my cell-chatting shadow abruptly vanished.

There's a reason a guy has to hike across a field full of burrs and ticks to get where he's going: His government has failed him. The city of Atlanta has a responsibility to provide infrastructure — roads, bridges, sidewalks, electrical, and water service — to its citizens. But unfortunately, in this the nation's seventh emptiest city, the money is not sufficient to serve a population occupying as much territory as we do, even if it is spent well, which is often not the case. It's like too little icing spread over too much cake. The obvious solution is to reduce the size of the cake, but there's no easy way to do that — simply put, those on the margins are priced out of the core. And so they remain on the margins and make their own infrastructure: footpaths through the wilderness.

It almost goes without saying that the people who live in these places are at a tremendous economic disadvantage. There’s a recent coinage, “food desert,” that wonderfully describes areas without ready access to decent food. But places like these are deserts of all sorts of things — transportation, culture, jobs, beauty, joy. It must be awfully hard to grow up surrounded by rotting houses and empty storefronts. At one point I saw a group of 5- to 7-year-olds playing in the yard of a dingy cluster of apartments while blaring rap music intoned to them, “that pussy, that pussy, that pussy.” Grotesque, to be sure, but it is it any worse to be a child in a world where the most effusive demonstration of government money and power — indeed perhaps the only evidence of government’s existence at all — is the sprawling prison next door?

After passing the last and gloomiest of the grim little apartment complexes that dot McDonough Boulevard, I passed into a sort of silent, empty purgatory. The land opened up somewhat — less of the wild vegetation that defined most of the previous stretch, and fewer buildings as well, of either a decrepit or robust character. The change was signaled by the appearance of two historical markers in quick succession. The first detailed Hood's evacuation of Atlanta on Sept. 1, 1864 — the route taken in this event was, ironically, the same as that taken by Hardee on the night of July 21. The second marker was a reminder that I was, in fact, still on the scent of Hardee's march. I found it covered with graffiti.

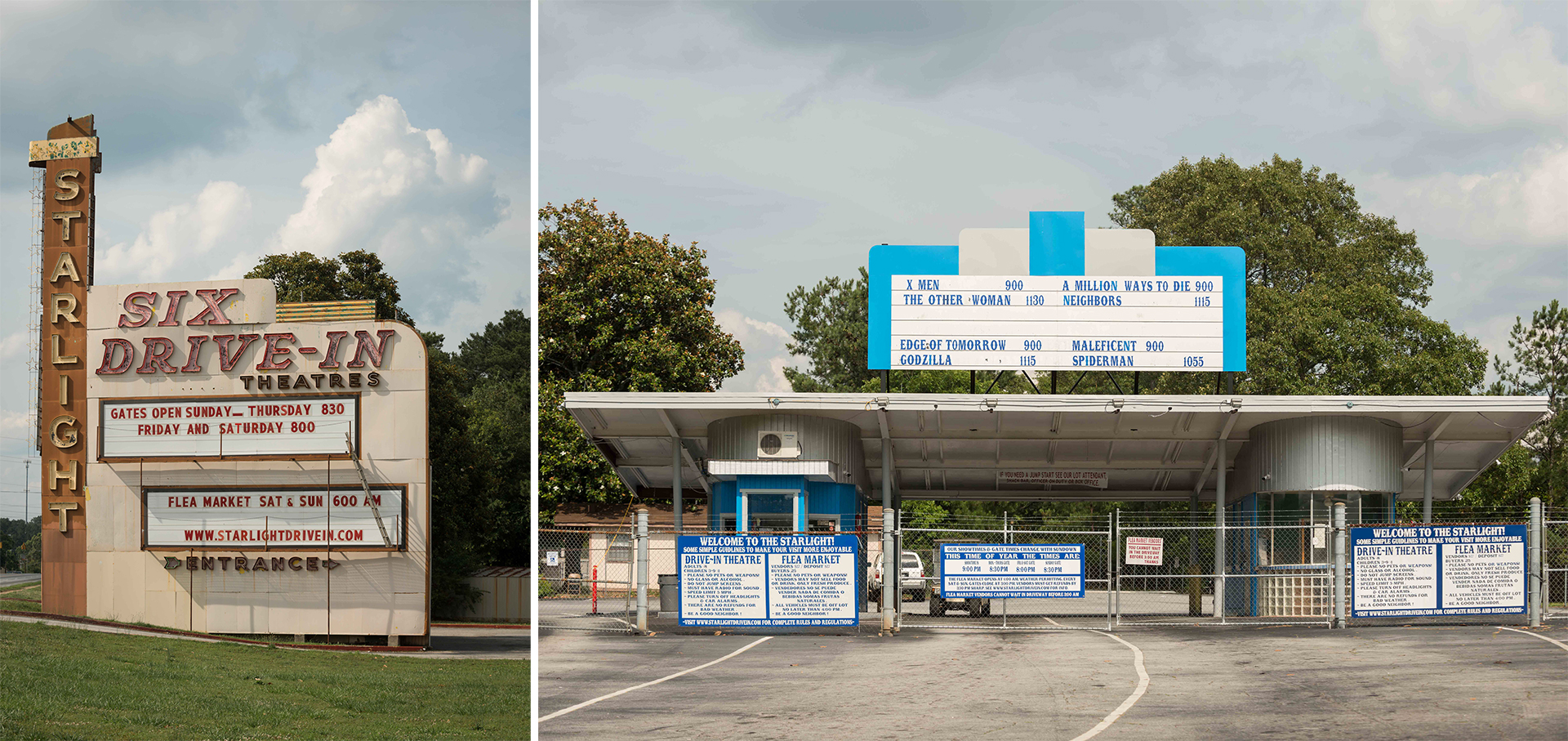

Reaching Moreland Avenue, I turned south. Hardee's route at this point is fuzzy — Moreland didn't exist at the time. Whatever the specifics, it was something of a relief for me after the desolation of McDonough Boulevard, to arrive in a region exhibiting at least a modicum of economic activity. And though it can hardly be called thriving, the area does sport one of Atlanta's treasures — The Starlight Drive-In. This 65-year-old paean to the art of tailgating survives, no doubt, due to the supreme undesirability of the surrounding land. Sometimes a poor location is a good location.

The rest of the journey down Moreland was unremarkable, save for traffic density, which was the highest I was to see all day, and a tiny notebook I spotted on the sidewalk. I picked it up and rifled through it as I walked. It was a diary, presumably written by someone living nearby, full of depressing stuff like this:

Goals

Find a new home for my family.

Help De get her a new car.

Get me a new car.

These goals I have set for now.

Stay Focus is my motto.

Stay focus. It’s a good motto, isn’t it?

At length I arrived at Fayetteville Road. It was at this juncture that Hardee judged he had gone far enough south to be certain his movement would be masked from the Federals. His men, and I, turned to the northeast.

The change wrought by this turn manifested at once. Suddenly I was no longer in Atlanta, the 11th largest metropolitan area in the United States. I had entered a wilderness. There were no more sidewalks. The road was lined with neck-high grass and brambles, followed hard on by thick woods. I was out of water (and Coke) and had seen no place along Moreland at which to refill, but I wouldn't have guessed this wilderness would extend as long as it would turn out to. Poor judgment, that.

Fayetteville Road was not without residents, but their houses were scattered at a fairly good remove from one another. At the least they did evince some signs of vitality — mostly in the form of heaps of plastic toys, or pieces thereof, strewn willy-nilly in backyards amidst the carapaces of cars perched gingerly on concrete blocks. I crossed a lonesome railroad track and shortly thereafter passed some sort of small warehouse still in operation but very much in danger of being swallowed by the vegetation, as was the police training academy a few hundred yards past that. The frequency of houses declined and finally all signs of present civilization passed away like a scrap of newspaper in the wind, leaving me in an empty and silent landscape. Yet every now and then a break in the trees would provide an incongruous view of the skyscrapers of downtown Atlanta just a few miles distant and yet as far economically and psychologically as if they had been across an ocean.

After a time with no sights but the trees and grass and no sounds but the buzzing of cicadas, I spotted a pair of kids walking toward me with a camera tripod. A guy and a girl; I wondered how they would react to my appearance in this desolate wasteland. I didn't have to wait long — they hailed me at some distance to ask if I was taking photographs. Yes, I said, and explained my journey. The girl told me that I was almost on top of the old state prison farm. They indicated a break in the brush up ahead, where I might cut through onto a path that led to the prison buildings. Now, you may think me a fool, what with my parched throat and empty bottle, but this was something I couldn’t resist.

The state prison farm is a boon to the sort of people that keep spelunking gear around for the purpose of exploring rotting buildings. For the rest of Atlanta, not so much. It opened in the early 1900s and closed around the early- to mid-1990s, and during its life it collected a checkered reputation as a dumping ground for undesirable populations — blacks early on and the homeless later. Since its closure, it's been left simply to decay — an object of contention between the city that owns it, Atlanta, and the county that houses it, DeKalb. It would make an excellent city park, but instead, for almost two decades it has served as an illicit playground for fringe types — drug users, homeless people, graffiti artists, and the occasional tourist of rot such as myself.

I walked along the quiet curving road that led through the trees, unsure what to expect. A building emerged. White concrete, blanketed in kudzu, with a steel staircase on the near end. I approached it, crossing a smallish asphalt lot with a basketball hoop on one side. I climbed the rickety stairs and peered down a long, trash-filled hallway pierced on either side with open doorways. One of these was close at hand and fairly beckoned to me, so I walked a few feet down the hallway and peered in.

I was presented with a view of a long concrete room which I assume was once a dormitory. In a manner of speaking, it still was. The floor was covered with detritus indicative of countless camps: the remains of a fire surrounded by flattened cardboard boxes and filthy sheets and blankets, empty food cans, booze bottles, newspapers. Glancing to my right I saw a metal frame which may once have been bunk beds. Someone had hung a profusion of rubber chickens and doll heads from it. And then, looking back to the camp area, something shiny caught my eye — an enormous meat cleaver.

Too weird for me. A few feverish minutes later I was back on the road with Hardee again, hauling my cannons up Key Road in the ever-growing heat of the afternoon.

Photographer Brett Falcon traveled the same path as Gen. Hardee — and our writer Fletcher Moore.

These are some of the people Brett met along the way.

Back on the road, I rounded a curve and came to two more historical markers. These were the first I had seen in quite some time (the one located at the corner of Moreland and Fayetteville appears to have vanished some years ago). They detailed Hardee's pre-dawn arrival at the now long gone Cobb's Mill. Here he procured guides for an upcoming wilderness march, or at least, so read the marker. I am unable to find any indication that either Key Road or Bouldercrest didn't exist in 1864, but I suppose it's reasonable to assume that either or both may have been little more than goat tracks and possibly unreliable or laced with frequent off-ramps. At any rate, it is clear that confusion was beginning to set in for Hardee, and it's understandable why. Even with my fancy iPhone in hand I had difficulty judging the distance to the next convenience store, whereas Hardee and his men lacked not only the convenience store and the iPhone, but also the promise of a ride home once they reached East Atlanta. The greater likelihood for them were permanent resting spots in Oakland Cemetery.

It had been a good hour since I'd last had a drop of liquid, and the cool weather of the early afternoon had given way to a smothering blanket of unbreathable air more or less at the same moment the path began a grueling climb to Bouldercrest Road, still over half a mile distant. I was parched. Perhaps dangerously so.

To my great shock, the next feature I passed turned out to be a water treatment plant.

My natural assumption was that there was no better place in Atlanta to procure a glass of water. As I approached the somewhat intimidating guardhouse, though, I received a rude awakening. One of the guards popped out of the door and she asked me to explain myself even though I was still 50 feet distant. "Can I get some water?" I shouted. Her reply was as terse as it was negative, and I wondered, were I to simply drop dead in front of her, would my body find its way back to my family, or would it slowly make its way, molecule by molecule, into the water of nearby Intrenchment Creek, to be filtered out in this very treatment plant and subsequently be sprinkled in powder form on the farms of South Georgia?

So onward I trudged. I went perhaps 200 yards, and for the first time in the day the wilderness at the side of the road was actually inviting — a large field of clover lay to my left, so into it I went. I gratefully flung my gear and myself to the soft, cool ground.

There I remained for 10 minutes, watching the cars zoom past on their way to purchase jugs of iced tea and bags of candy bars. I was in a bind. I knew I was overheating, and I knew that to go on would probably mean heat exhaustion, with its attendant vomiting and headaches. Perhaps heat stroke would follow, with its attendant coma and death.

Still I couldn’t bring myself to call the rest of the trek off.

At that moment, a big white Cutlass Ciera passed, slowed to a stop, and began to back up. My mind immediately turned to developing cutting remarks in the event, greatly anticipated, that the driver was simply looking for an opportunity to exercise his anti-pedestrian wit.

But the Ciera proved to be the chariot of an angel. The driver, a plump black woman in her late 40s, leaned out the window and shouted, with concern visibly etched on her face, the words I least expected, "Do you want some water?”

I sprang to my feet like I’d been shot out of a toaster and skipped toward the car.

"You have water?" My voice fairly trembled.

"Well, I don't have water, but I have Gatorade."

She handed me a 20-ounce bottle, painfully cold. I told her my mission — she nodded, somewhat blankly but with an amiable smile — and she told me that she and her husband were building a house near the Starlight. She was on her way to pick up supplies of some sort and just happened to be carrying a cooler full of Gatorade. What are the chances?

"Can I take your photo?" I asked. She assented, and I ran back to my piled-up gear, trying to keep my giant buck knife well out of view. I suddenly felt embarrassed to even possess it. I took a couple photos and thanked her as profusely as I was able. Then off she went.

I emptied the entire bottle in one long pull.

Feeling much refreshed, I shouldered my pack and continued up the hill. Intellectually I knew the Gatorade had had its impact, but the way was steep and long. By the time I emerged onto Bouldercrest Road, I was already casting about in minor desperation for more liquid. I sat down on a short brick wall and rested for a long while. At this stage I was not only hot and thirsty but bone-tired. My feet felt swollen and my legs ached severely. Getting under way again, I began to feel that every step was a conscious effort.

It's not as though I'd never walked anything like this distance. I can only assume that it was a combination of the heat, the dehydration, the hills, and the weight of my pack that was reducing me so savagely. I can't imagine that Hardee's men would have been free from the same difficulties, and many others besides. It must have been a weary army indeed that approached the Federal lines in the late morning of July 22, 1864.

The neighborhood was ratcheting upward in terms of affluence, and was denser than any I had passed through since leaving Grant Park. Earlier in the day I might have welcomed this change, but curiously it seemed to drain all my interest, to turn it from an invigorating backcountry adventure into an enervating slog through the all-too-familiar autopia.

Before long I came to a fork. Bouldercrest led northwest toward East Atlanta. Fayetteville led northeast to a point just past I-20 where the interstate curved south. It was here, already hours late and in some disarray, that Hardee made his final, fatal mistake. Lacking sufficient information about the two roads and his own position, he divided his army, sending generals Clebourne and Maney with their divisions toward East Atlanta, and Walker and Bate to the east, where Walker would shortly meet his doom. The former pair would become tangled up with McPherson's reserve, which he had wisely sent south from their camp in Candler Park against the possibility of just such a flanking move as this. The other pair, while undeniably testing the mettle of the Union troops, was too diminished and too weary to finish the job. Had the entire corps taken the eastern road, events might taken a different turn.

Or perhaps not. In retrospect it's pretty easy to see the fight for Atlanta for what it was — the final throes of a defeated rebellion. The fall of Vicksburg in July of 1863 had already cut the Confederacy in two, and the conclusion of Gettysburg the day before extinguished any reasonable hope of deliverance from external powers. It takes a generous helping of fantasy to see any kind of path to victory for the South after that point.

Cooler heads would not, of course, prevail for a good while longer. The Battle of Atlanta was a loss for the Confederacy, but it wasn't decisive. Hood held out for six more weeks before fleeing the city. Even then he wasn't done: His army ultimately made its way to Tuscumbia, Ala., whence he launched a hopeless stab at middle Tennessee, which earned his men graves in Franklin and Nashville but no appreciable strategic improvement for the Confederacy. Sherman, meanwhile, largely ignored Hood, marching onward to the sea in a path some 30 miles wide, making a powerful point: The Confederacy could no more stop him from going where he wished than they could stop the rain.

Meanwhile, in Virginia, Gen. Robert E. Lee was checked again and again by Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, frantically searching for a way out until he simply had no moves left. The determination of these men to soldier on in the face of futility is often taken as a sign of their fighting spirit. I'm inclined to think it was just a bullheaded refusal to face the failure they had wrought. This may not be a characteristic unique to the South, but there can be no doubt that the South has long walked arm in arm with denial.

And still does.

Historical sources always make reference to Hardee’s 15-mile march, as indeed I have up to this point. The route followed by Walker and Bate may have been closer to 15 miles, but I can’t see any way to stretch Clebourne and Maney’s march beyond 10. Whatever the explanation for this discrepancy, my hike was about 10 miles.

In those 10 miles, I passed through racial barriers that that make hay out of integration. I saw vast swaths of land mired in something close to third-world poverty. The old saw is that Atlanta is the city too busy to hate, but when you get out of the car and press your feet against the soil, it becomes hard to shake the feeling that it's really a city too busy to give a rip.

Well, that might not be entirely fair. Any moderately perceptive resident of the city quickly gets a sense of the anti-Atlanta vibe coming from the rest of the state. Legislative season is more like a cavalry raid than a function of government, with some legislators declaring their eagerness to leave town before they even arrive.

The charitable view of Atlanta might be that it's a city with a lot of problems, and that its people are doing the best they can to address them. To a Confederate hunkering in the Georgia wilderness like a Japanese soldier on some Pacific atoll in the 1970s, the idea that Atlanta, one of the capitals of the Rebellion, would dare apply a liberal solution to problems of race and class (and more recently, sexual orientation) would have been anathema.

But our modern die-hards aren’t isolated and living off grubs and roots. They are in positions of power, and so Atlanta continues to be besieged.

As I trudge through East Atlanta and drop myself on a bus bench to await my ride home, I can't help but think of the one detail of the battle that seems to escape the attention of those who identify with the “lost cause”: When Hood finally gave up the ghost and fled the city, it was he who lit the first match that burned Atlanta to the ground.