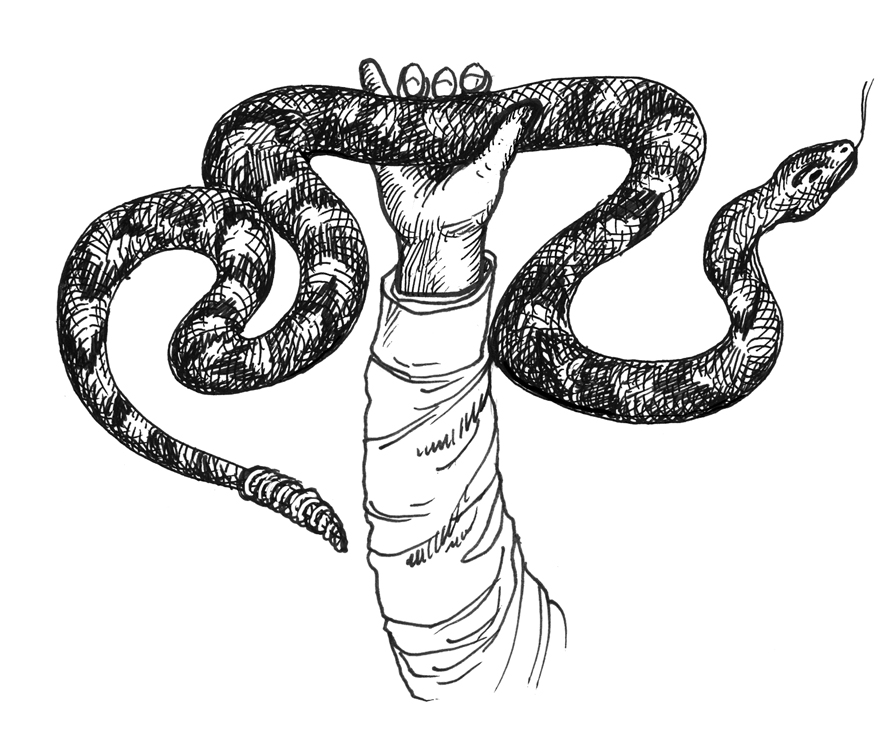

The Pentecostal Serpent

Sometimes, God holds back the snake. Sometimes, He sends you to heaven.

Story by Asher Elbein

The serpent’s tongue flicked from scarred lips. Its fat brown body coiled in the palmetto, black eyes glinting in the dim light. The forked tongue touched the glass and retreated, touched and retreated, steady as a metronome. Without that flicker of motion, the snake would have been invisible, one more piece of driftwood lost in the shadows thrown by the branches and wire mesh atop the display.

“You ever seen a serpent handler’s snake?” the zookeeper said. His cut-up arms bulged from a work shirt emblazoned with the logo of Zoo Atlanta. He passed me twice before he spoke, the two of us alone in the gloom of the reptile house, with nothing but the rustle in the cases for company.

“Never have,” I said. “That’s a cottonmouth, right?”

“Sure is,” the keeper said. He nodded at a lonely rope divider, meant to hold the public a few feet away from the glass. It was the only such barrier in the building. “That’s a Pentecostal snake. You come close, she’ll strike at you through the glass and smash her mouth up. She’s done that a couple times already, you see? That’s why we’ve got the rope. She’s an angry snake, Jack.”

I looked down at the rope divider. The cottonmouth’s head tracked my movement. “Where’d she come from?”

“Donated,” he said. “Came off some Alabama snake handlers. Apparently she bit a few too many. Some people died.” He looked down at the heavy brown coils with a beatific smile. “We call her Preacher Killer.”

I laughed. “She’s that mean, huh?”

“Not mean, Jack,” the zookeeper said. He nodded to me as he left. “Just angry.”

The cottonmouth’s jaws opened in slow, threatening gape. Its gums glowed a ghostly white. Above the open mouth its eyes glittered, unblinking. I met its gaze for a long time before I walked away.

I thought of Preacher Killer now and then, in the following months. I knew nothing about serpent handlers at the time, having grown up Jewish in Orthodox neighborhoods in Dallas and Atlanta. But I loved reptiles, and 20 years of experience of turning over logs and scrambling down ravines had taught me a lot about snakes. I’d seen them agitated, made aggressive by fear or territorial instinct. Never anything deeper than that.

But if any snake was angry, it was that one. Angry enough to bash her own face in by striking against solid glass, striking at anything that came close, striking from the sheer existential rage of a snake born into a world filled with people. Had she hatched that way, I wondered, or was that anger born in a wooden box, buffeted to life by holy hands? Who were the people who had kept her?

What was life like for the Pentecostal serpent?

The Reptile House at Zoo Atlanta Photos by J.R. Ward II

The origins of serpent handling lie in the old folk traditions of the Appalachian mountains, a place where scripture and snakes were in generous supply. But the ritualized handling of snakes attained national prominence in 1910, when a traveling preacher named George Hensley began including it in his sermons. For textual justification, he pointed to the verse Mark 16:18, where handling serpents was listed as one of the signs of those faithful to God. Clearly, Hensley argued, that was a command to take up venomous snakes. (Non-venomous snakes are not considered to be serpents.)

For a time, his contemporaries agreed with him. Appalachia was still caught up in the great revival, a wave of Holiness and Pentecostal evangelizing that swept across the country and promoted ecstatic, emotionally charged forms of worship. Adherents were compelled by the power of the Holy Spirit to speak in tongues, cast out demons, heal with their hands. Any man could preach, if he felt the spirit. Serpent handling was an escalation, a powerful ritual that drew crowds of believers and sceptics alike. The practice spread quickly, sister congregations popping up like mushrooms across the hills.

The snakes themselves were transformed, no longer dangerous vermin or vague symbols of evil, but conduits for the will of God. In a sermon at the height of his powers, Hensley compared serpent handling to other forms of biblical deliverance: Daniel in the lion’s den, Jonah in the fish’s belly. “But that was before your time,” he called to the crowd. “I’ll show you something of your time. I’ll show you how to handle the rattlesnake. And you all know the result of a rattlesnake!”

Photo from the archive of Dr. Ralph Hood

But reporters knew the result of a rattlesnake too. As the dangers of the practice caught up, articles about fatal snake bites appeared in The New York Times, in The Chattanooga News-Free Press, in any number of local papers. By 1955, there had been at least 35 confirmed deaths as a result of snake handling. One of them was the 75-year-old Hensley, killed by a five-foot rattlesnake on a boiling Sunday afternoon in Florida. By then, the Holiness and Pentecostal assemblages had disavowed the practice and every Appalachian state (with the sole exception of West Virginia) had banned it. What had been an exciting new religious practice was cast to the margins of American religious history and left to die.

But a few serpent handling churches hung on, underground, in the tangled hills and rural communities of Appalachia. There they developed their own traditions, independent of the wider denominations, and often independent of each other. For a while, they were one of the South’s open secrets: backwards, backwoods people, shaking their snakes, rating somewhere between a curiosity and a joke.

That changed in the 1990s, when a preacher named Glenn Summerford got drunk, put a gun to his wife’s head, and forced her to stick her hand into a crate full of rattlesnakes. She was bitten twice before she managed to escape and call the police. Her ordeal – and Summerford’s subsequent conviction for attempted murder – drew national attention. Journalists once again flocked to services. Cable channels, desperate for content, discovered in serpent handling the perfect excuse for a steady stream of lurid documentaries and reality shows.

Most congregations shied away from the limelight, but some – especially those led by young, telegenic pastors – saw the attention as a chance to boost their ministries. One of them was Jamie Coots, Kentucky preacher and star of the 2013 reality show "Snake Salvation." For 16 episodes, Coots invited producers into every aspect of serpent-handling life, and he used the publicity to invite skeptics to his church. Then, in February 2014, he died of a timber-rattler bite during services. His passing prompted its own wave of sensationalist coverage, further wrapping serpent handlers in a televised enclosure of strangeness and death.

The news stories shook something loose inside my brain. It had been two years since I had seen Preacher Killer, and as a busy undergraduate, I’d hardly had time to think of serpent handlers. The death of Jamie Coots brought back half-forgotten memories of that angry cottonmouth in a glass case, memories tangled up in snatches of film and hazy imaginings. What little I knew about serpent handlers came from the television, and that information now seemed simple and shallow. I wanted to know why Coots had picked up something he knew could kill him.

And at the back of my mind, I wanted to know about the snake.

The locus of academic research on serpent handling resides in a tiny, book-choked office at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. Broad wooden boxes and the shed, flaking skins of rattlesnakes line the walls. The office belongs to Dr. Ralph Hood, a professor of religious psychology who’s been studying the practice since the 1970s. Originally, Hood said, serpent handling was academically dismissed, a deviant tradition of a culturally impoverished people. That’s changed over time, as scholars have been more willing to view the practice as unique and interesting in its own right. Hood himself has amassed hundreds of hours of recordings, interviews and video footage of services, and is on good terms with handlers all across the mountains.

But legislative attitudes have not kept pace with academic ones. Serpent handling is still illegal in most Southern states, and practicing churches are occasionally raided by police. This is constitutionally tricky, however, so states like Tennessee have recently chosen to pursue serpent handlers for violating laws about wildlife collecting. Officially, the purpose of the ban is to protect people from snake bites. To Hood, that’s a flimsy rationalization, meant to hide the fact that Southern legislatures have long viewed the tradition as distasteful.

“Driving to church is pretty dangerous,” he says. “But nobody’s going to ban cars. The argument that the states are protecting people from a religious activity reveals the bias. We allow all kinds of high-risk activities in the secular world. But serpent handlers are taking a serious risk during a religious ritual, which is something other Christians don’t do.”

No mainstream religion in America does. Secular risks are often brushed off as the choices of consenting adults. But religious risk is not something American thought has a frame for, and ecstatic worship in general is usually viewed as the province of the poor. It's not hard to see why the larger revival groups, in a bid for mainstream acceptance, toned down their services and removed the riskier elements. In return, they’ve reaped the rewards of rich donors and massive congregations. Mainstream Christians – the kind who sit quietly in church, live comfortable, middle-class lives, or get elected to state office – would never do anything as outré as dance with a rattlesnake.

This suspicion leads state authorities to assume that taking up a serpent is, effectively, suicide. In fact, the risks are more complex. Six types of venomous snakes are found in the South, and serpent-handling churches make use of all of them. There’s the copperhead, the color of a dead leaf and shy; the burly eastern diamondback with its ridged scales and chocolate spangled hide; the tawny timber rattler, lean, yellow, and lethal; the grey-black pygmy rattler, small and rare; the coral snake, smaller and rarer. And of course, there is the cottonmouth, fat, hissing, with long fangs and a mouth the color of snow.

Handling any of them is a daunting prospect. But surprisingly few people get bitten, a fact that is commonly attributed to some kind of trickery on the part of serpent handlers. In fact, Hood’s research suggests, a person’s chance of being bitten is fairly low, especially if they only handle occasionally. Venomous snakes are calmer than we give them credit for, he says, and they can become accustomed to being held and thus less likely to bite. Other researchers disagree with this explanation, suggesting instead that the common practice of crowding multiple snakes in a single box leaves the animals sick and parasite-ridden, unable to muster up the energy to strike. There’s some evidence for this line of thought; a group of snakes confiscated from a church in Tennessee were so sick that Michael Ogle, a curator of herpetology at the Knoxville Zoo, was forced to have them put down rather than risk the rest of the zoo’s collection.

Hood brushes this off. Yes, he says, some of the snakes are sick. But most of them are freshly caught before every service, and are released soon afterward. Handling sick snakes would be like handling non-venomous snakes, and that would defeat the purpose. The point is to have enough faith in God to take up something wild, untamed and unpredictable.

That unpredictability, however, is the root of the danger. However acclimated to humans a snake might be, it’s never truly tame. The more often a person handles, the greater their chances for a bite. Bites aren’t necessarily fatal: Toxin is both metabolically expensive for a snake to produce and its only tool for subduing prey. So snakes often give “dry bites,” warning nips that inject none of their precious venom. A full bite from some vipers, like the copperhead, is easily survivable. Contrary to popular belief, though, it's impossible to become immune to snake venom. Instead, successive bites often lead to worsening allergic reactions. Hensley claimed to have been bitten more than 400 times before he died. Coots was bitten eight times before he received the killing strike. Handling snakes is not a death sentence, but any handling could be your last.

Practitioners are well aware of this. There’s a constant repetition in recorded interviews: Don’t take up a serpent if you don’t feel the Spirit. Don’t handle for show. There’s death in that box, boy, and you open it at your peril. At the same time, they embrace the risk. Life and death rest entirely in God’s hands, they believe, and whatever happens while handling is His will. Sometimes He holds back the snake. Sometimes He calls them to Heaven. It’s not something they expect the rest of the world to understand.

It’s difficult getting invited to a serpent-handling church these days. The publicity surrounding Coots' death forced the smaller churches to adopt a siege mentality, with any requests for interviews or recordings met with flat denials. Still, Hood provided me with a contact: Billy Summerford, the pastor of a little church in northern Alabama and the cousin of Glenn Summerford, who tried to kill his wife with a box of rattlesnakes. A week later, I drove up the winding roads and along the eroding flanks of Sand Mountain, toward Macedonia, Ala., and Billy Summerford’s church.

I arrived at sunset. Tides of blue shadow washed along the trees and swallowed the pitted tracks, calling up a chorus of peeping frogs. The church – white clapboard, weathered and sunken – sprawled behind a gravel parking lot filled with pickup trucks. Summerford stood outside, a heavyset man with greying hair and hound-dog eyes.

He looked at me as I climbed out of my car. “You that Texas boy?”

I had not told him that I was from Texas, but I was wearing an old black hat and I suppose he guessed. “Yep.”

“Well, good to see you.” He pumped my hand. “Go on in, find yourself a seat.”

I went up the creaking steps and slipped inside. Unlike the innumerable brick Baptist churches scattered across the fields of Macedonia, the Summerford church was entirely made of wood, with low ceilings, scuffed green carpeting and an atmosphere heavy with the scent of sweat and old plywood. Rows of pews took up much of the room, with the stage at the other end separated from them by an expanse of open floor. The stage itself was crowded with a pulpit, electric keyboard, numerous guitars, and a drum set. Above them hung a huge wooden cross and a pair of scuffed speakers. At the foot of the stage sat two wooden boxes. Snake boxes. About 30 people showed up that night, most of them either under 15 or over 40. They found their seats slowly, stopping to shake hands or kiss each other on the cheek, children running in shrieking patterns across the floor. Everyone in the congregation made it a point to come shake my hand and tell me how happy they were that I was there.

Photos from the archive of Dr. Ralph Hood

Summerford took the stage, accompanied by four women from the congregation. He called for a silent prayer first, as the women tuned guitars and checked the drums. He called out the names of the sick, the words “remember them” spoken after each name and greeted with a mutter by the congregation. Then cymbals crashed and drums pounded, and the women on stage launched into a thunderous set of hymns. The congregation sang along, beating tambourines and triangles, stomping and clapping to keep time. The energy built in the room, twisting in the air, until one of the men crumpled, head jerking, mouthing strange words. Those around him laid hands on his shoulders and back as he twitched, head bowed under the weight of some invisible force. Summerford stood above him on the stage, eyes closed, hands up toward heaven.

The floor shook under the stamp of feet, sound echoing and curling in dissonant tapestries. Another man snatched up a glass bottle filled with flammable liquid, lit it, and held the flame to his throat as he danced. “Jesus,” he shouted. The flame danced, in and out, licking his throat. “Jesus.”

Then the music died down. The flame was blown out, the bottle replaced. The snake boxes remained untouched. Summerford sat as a narrow-faced man took the stage, a bible in his hand. “Modern life will make you sick!” he said, patrolling back and forth like a wading bird. He flipped the Bible open and began to speak, glancing down occasionally to help himself along. “They’ll give you medicine that won’t help, and pills that make you feel worse. But Jesus won’t give you none of that!”

“Yes, lord,” said a woman in front of me, her eyes closed and her head rolling.

“Jesus gives you salvation and life everlasting. There’s trouble and pain in this world, there sure is, but in the next one, all will be healed.” He thumped the pulpit, his voice conversational. “I was going to the store and the folks behind the counter asked me what church I go to. I told them that I come here, to the Holiness church, and they looked at me like I was crazy. I said to them, 'Boys, you had no problem with me before you knew I was a serpent handler.' They don’t believe what we do is real. But it’s a real thing, isn’t it?”

“It is,” called the congregation.

“It’s a real thing,” the man said. His eyes swept the congregation, never quite landing on me. “I been to services with strangers, come to see the snakes. The Lord held us down and wouldn’t have us handle, so that his grace wouldn’t be profaned. But we know the truth, don’t we?”

“We do!” shouted the congregation.

Then there was a gentle sound in the air, a sound that burrowed through the ears and danced along the spine. It was the warning buzz of a rattlesnake, muffled by wood, abstract, theoretical. Death in a box.

“It’s real, this thing,” the man said again, at Billy Summerford, at me, at the box. When he spoke his voice was soft, gliding along with the buzz. “It’s surely real.”

Photos from the archive of Dr. Ralph Hood

I visited the Summerford church twice more in the following month, and never once did I see them handle a snake. Perhaps they never felt called to do so. Perhaps they were wary of me, a stranger. The rattle in the box was the closest I ever got.

In the absence of serpents, the serpent handlers came into focus. Before the preaching, they leaned on the pews and gossiped, or talked about fishing trips, or shook their heads over politics. The kinds of things people do before every service, and the kinds of things that television cameras cut away. In this, the Holiness people are one more portion of Appalachia to be strip-mined, all context discarded, their lives edited into five-minute segments and half-hour shows. Hillbillies with snakes! See them sweat and jabber on your television, see them dance and wave vipers. Watch long enough, and you might see someone die.

Step back from the outlandish trappings, though, and what you see are a people who believe themselves chosen, anointed, the last folk standing against a fallen, secular world. In this they are not strange: Proud anti-modernism is a long-standing American tradition. If they are different from other strongly religious groups, it’s only by a matter of degrees: people willing to put their money where their mouth is.

But what becomes of the snake, when you strip everything away? That’s the more intriguing mystery, one that discussions of the topic inevitably orbit and seldom touch. Archives are stuffed with analyses, footage and recordings of serpent handlers. In all of these, the handled are present merely as snake-shaped hangers for human symbols. The serpent is Christ on the cross, or Satan in the garden, or Death waiting in the dusty road. Because we can’t know the answer, its experience of the proceedings is never asked.

I can imagine it, though: A rattlesnake sits in a crevasse beneath the folded rock, a copperhead lays in the bracken, a cottonmouth hides in the reeds. Hands come down and pull the snakes from their place, stuff them in a bag, dump the bag in a box. The snakes wait, coiled in the dark, the wail of the electric guitar and the smash of cymbals humming beneath their scales.

Then the box is opened and they are lifted into the blinding light by sweating hands. Their pit organs burn with the heat of shouting people. Their tongues taste air thick with sweat, oil and mildew. A few snakes, timid or unconcerned, take it in stride. Some, sick, loll lethargically, already near death. Some snakes rattle or flash a white lipped threat. And some snakes strike.

Venom sacs contract. Poison courses up dilated veins toward its mark. The preacher picks up the serpent, and the serpent kills him, and we watch. This is the ritual we all play out, building boxes around each other: An animal's assertion of its autonomy becomes a moment of religious meaning, and the religious meaning is filtered through empty spectacle. A reinforcing coil of fascination and fear, a tangle of nested stories mistaken at every step for truth.

But the serpents are just snakes. The serpent handlers are just people. Everything else is a box, built to be peered into. Sometimes, the things in the box stare back.

Photo by J.R. Ward II

I never saw Preacher Killer again after that day in the reptile house. The next time I visited, the rope had disappeared and the case was occupied by a sleek, mild kingsnake. The scarred cottonmouth who had nearly broken her jaws striking at the glass was gone. Perhaps she was traded to another zoo, or released into the wild. Perhaps she struck the glass one too many times and was killed. I only remember her because the zookeepers gave her a name: “Preacher Killer.” The last box for an animal that lived its life in boxes, a perfect encapsulation of its expected role, a narrative shape concealing the real thing inside.

A few months ago, I nearly stepped on a wild cottonmouth, out in the tangle of swamps and fields behind the Tuscaloosa airport. It raised its thick body and opened its mouth in warning, gums shining white in the Alabama sun. I stepped back and stared at it, trying to see Preacher Killer in its black eyes, looking for the telltale infection of the divine. Looking for the Pentecostal serpent.

But it was just a cottonmouth in the dry grass. Eventually it grew tired of being stared at, and slithered away.