Welcome home from Labor Day. Few people ever put more muscle into American labor than Rosie the Riveter. Rosie is the iconic designation for the 6 million women who took up “men’s work” in World War II. The American Rosie the Riveter Association is headquartered in the South, and Camille Pendley visited their convention in June to meet some real Rosies. We think you’ll enjoy meeting them, too, and we expect you’ll forgive us the fact that some of these women are not Southerners. In this case, we don’t care, because they’re all worthy of honor.

Story and Photographs by Camille Pendley

You’ve seen the bandana-clad Rosie the Riveter icon in all her glory. While 350,000 American women served in the military during World War II, Rosie the Riveter represents the 6 million women, black and white, who took up jobs in factories, shipyards and elsewhere to support the war. Their support was critical: Women made airplanes and bombers. They worked in shipyards, building Liberty ships that brought food and other supplies across the Atlantic Ocean to soldiers. They worked in the War Department, now known as the Department of Defense.

The image associated with World War II workforce recruitment is of particular resonance now, with a woman on the presidential election ballot for the first time and combat positions of all types now open for women to serve.

When the war was over in August 1945, so was the women’s welcome at their jobs. Many were told to pack up and move out as veterans returned to fill their old positions. Few women were given the chance to stay, including those who lost husbands and sons in the war.

In June this year, “Rosies” from all over the country gathered in Atlanta, Georgia, the birthplace of the American Rosie the Riveter Association. It was here that these women — now in their late 80s and early 90s — came together to share stories from their time supporting war efforts, when many of them were just 16, 17 or 18 years old.

Jane Tucker had never seen a boat when she, her sister and single mother left their Alabama town of 1,000 to work on a shipyard in Savannah. At 16, Jane worked as a welder on Liberty ships, which brought food to British soldiers across the Atlantic before the U.S. entered the war.

When we took the jobs, especially all of the manufacturing jobs, we had agreed that we’d go back home — that they (the men) could have their jobs back. And so that’s what happened. But it was so unfair, because the only jobs to go back to were as waitresses! At 14, I worked at the nickel-and-dime store and made a dollar a day on Saturday. And when I went to work at Southeastern [Shipyard], my starting pay was $1.20 an hour. That’s a lot more.

So, did society’s need for women to join the workforce en masse make a difference for women?

Oh, I know it did, darling. The women who [as Rosies] learned that they could do anything, and do it well, taught their children that. And so, look what has happened! We opened the door for Hillary Clinton!

Needless to say we went to the USO (United Service Organization) every night, and they’d take us to the base to dance.… I met all these wonderful guys, boys really.

A lot of ’em were ‘damn Yankees,’ and that’s exactly how my grandfather talked about ’em, and he helped raise me. He was 7 when the Civil War ended, so he remembered what the Yankees did when they came to the South.… He hated Yankees. And I was afraid of ’em!

But after my experience in Savannah knowing these wonderful ‘Yankees,’ I really was not afraid when I got to Chicago. I was scared to death of the big city, but I was not afraid of the people. People are wonderful wherever you are. That’s what I learned from that experience.

Up until 1941, you know it was really a man's world. And when WWII started, and women filled the men's shoes, they didn't realize what American women were capable of. And we sure proved what we could do.

I built B-17s and B-29s in Seattle, Washington, for Boeing. That was my story. Loved it. It was a great time in women's lives. It wasn't my job, or your job — it was our job. And we were just there to do a job and win the war.

We worked with gold-star mothers — that's a mother who lost her son. And she didn't stop working because she lost her son. She said she wanted to continue to work so another mother didn't lose her son because he didn't have the equipment he needed.

Mae wears a dog tag given to her on the runway of an airshow in Reading, Pa., where she was admiring B-17s and B-29s like the ones she built in the 1940s

My wish, My twilight”: Mae Krier says she travels around the country telling stories from her time as a Rosie with support from the Twilight Wish Foundation.

They ask me if I'm a liberal, I say, “No, I don't think I'm a liberal. I'm an ‘equal righter.’’’ I think it's only fair that a woman should get equally paid, the same as a man, when they're doing the same job. We did it; I can do it.

And you know, I met a sailor — a cute sailor — on the dance floor in Seattle in 1944. We had such a good life. We were both good dancers. We were married almost 70 years.

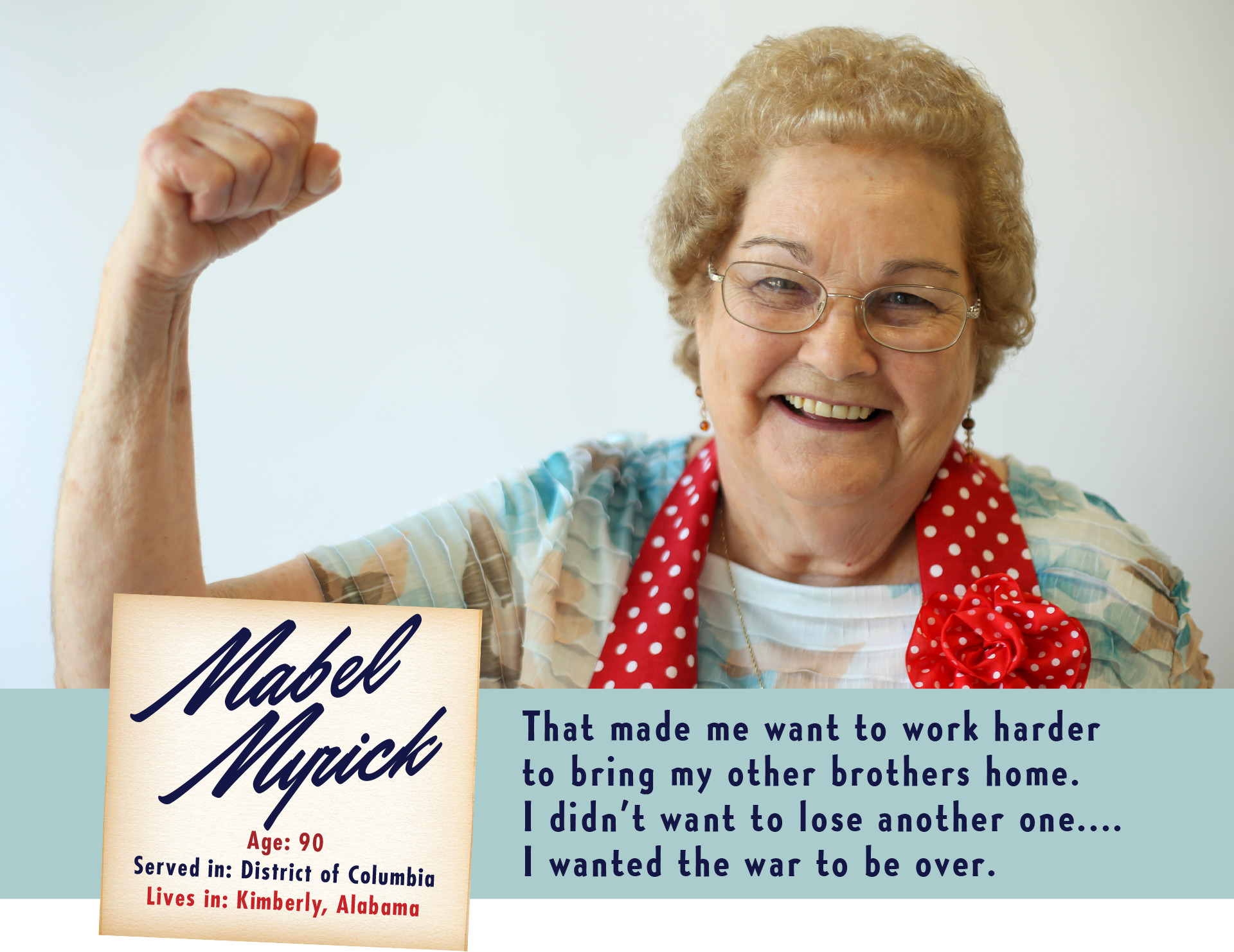

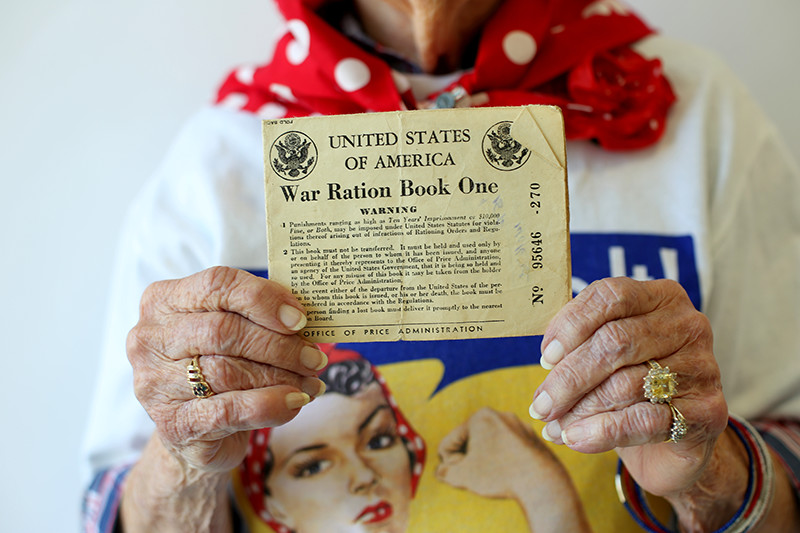

Just before I graduated from high school, a man from the government came around offering any of us who took shorthand and typing or bookkeeping a chance to take a government test. When I got [my results] in the mail, it had a train ticket to Washington, D.C.

Mabel was one of two secretaries in her department at the Pentagon.

I had never been out of the state of Alabama except once!” — a day trip on the train to Atlanta. “I was excited about being able to go to a big city like Washington, D.C.

I was overwhelmed by all the busy streets and many big buildings … and all the attractions that were there. I made a lot of friends from different states, and we would go sightseeing on the weekends and see everything there was to see.

One of Mabel’s four brothers was killed in action in November 1944, five months into her time working at the Pentagon.

That made me want to work harder to bring my other brothers home. I didn’t want to lose another one.... I wanted the war to be over.

Mabel was one of the few given the chance to keep her job when the war was over. She and others were cleaning out their desks when her boss asked her to meet him in his new office. She arrived to find an empty desk with an application on it. He changed divisions and kept her on as secretary in his new role.

On the convention: Well, I just think it's real nice to get to see people our age, you know, still able to go and do. And to hear their stories, it brings back memories of when we were working.

On being a Rosie: Well, I'm proud of it. I'm proud that I was able to go and work and do and help the servicemen.… They did not have things to fight with because the United States didn't think they'd ever have to do war.… We had to file in and do work that the men was doing so they could go and fight.

When the war broke out … the women were all swooped up. Over 9 million of us were needed.

Milka Bamond, born to a miner in West Virginia, served as a Rosie in Detroit.

Automotive city! A lot of girls came up from the South.… We'd never been away from any of our small towns and we'd be in a big city.... At some point in our city, there was actually a drive going from door-to-door persuading them to come to work.

I was a riveter. We were making wing and tail sections [for airplanes] … and there were so many workers, it was like ants all over the place. Shoulder-to-shoulder, barely enough room to move around. Everybody knew what they had to do. It was very organized.

When Japan declared war … they miscalculated! They thought because we were involved in the European Theater and we had very little as a war machine, that if they attacked us on the other side of the planet, it was a done deal.

So that's what really fired us up and put us over the top! … That's how it was — everybody was just gung ho, you might say. We had to save America! That's what it was all about.

It was a frightening time for America. And to see us here, old women in our 80s and 90s — some are younger, of course — but it brings back the spirit of what held America together, and it was patriotism.

It seems to be nonexistent right now.

During the war, everybody was working. Everywhere you turned: “We need you. We need you to come to work.”

Fran grew up during the Depression in a house of 12 — eight children, two parents and two grandparents. She worked as a bucker and riveter for Boeing in Seattle.

The boys were drafted, that’s why us girls and women all went. … We hardly had any boys left in the whole high school because they all left for the service! When I first started out [working], honey, I got 69 cents an hour. When I left there about six months later, I was making 72 cents an hour. Big pay, huh? That ain't very much, kiddo! But then, at that time, I think we were only paying two bits for a dozen eggs.

In our home, there was blinds, you couldn't have lights showing anywhere.

Her family and others did this for civil defense purposes.

Why? [So] the Japs couldn't see you if they came over there by chance! All of our buildings even, like up in Seattle, all of those buildings where we were working and stuff was all with netting and camouflage and everything else where you couldn’t see it from the air.

But there was fun to be had as well.

It was a wonderful time.… There were a lot of soldiers around, and you were always bringing somebody home. You know how that is....

Another thing that happened during that time: We started wearing pants, because when we went to work, they made us wear overalls. We’d come down there with skirts or whatever on, and they’d make us put overalls on…. Ohh, then it became where we really started wearing pants!

I’ll tell you something else: The United States was all together. It just wasn’t like it’s been over the years. It’s just crap … a bunch of bullshit — pardon me — now.

I told Iris she struck me as tenacious.

I am. I'm Scottish, I will say. Let's get this over with.... Yeah, I can talk. I was on the debating team for four years, and it helped me a lot in my work.

Iris, one of six children, all boys but her, worked as a riveter in Fairburn, Ohio.

They wanted us to wear lipstick in the jobs that we had. You want to know why? We had to wear pants, and nobody — women didn't wear pants back then. So they said, “Put the red lipstick on, so we'll know you're a woman rather than a man.”

They didn't make much of us then. In fact, the day after Hiroshima was bombed and the war was over in Japan, they came in and told us that they didn't need us anymore and “Goodbye.” And that was about it.… We just gathered up what was ours and walked out. It felt like we were kind of being deserted. I also felt like there might have been a nice way to show us appreciation … like have us for lunch or something.

But we were so glad the war was over, that was secondary. It really was.

Iris left the interview as abruptly as she began it.

I’m leaving now.

At 18, Constance was a technical illustrator supporting the Air Force.

I worked at two different places. I worked for Mr. Higgins in Michoud, outside of New Orleans, Louisiana. Mr. Higgins, he was building the great big cargo plane, the C-46. And it carries, of course, a lot of soldiers and equipment. I did charts for Mr. Higgins and plans for his activities and everything.

She then moved on to illustrating airplane-maintenance manuals, now kept in the National Archives.

It was a tedious job. I did the final inkwork. I would sketch them by hand — we didn’t have computers then.

Constance remembers leaving work at the New Orleans plant and walking past German prisoners of war detained at a camp across the street.

When we got finished working, they’d go crazy whistling at us — “Girls!!!”

Louise Unkrich, now 92, had been helping her father on their family’s Iowa farm when she went to work as a riveter and bucker an aircraft manufacturer after high school. Unkrich made B-26 and M-29 bombers at Glenn L. Martin Company and was a catcher for the company softball team. Glenn L. Martin, after a series of mergers, became what is now Lockheed Martin Aeronautics, based in Marietta, Georgia.

It didn’t take very long to know what was going on. They’d line up all the pieces and one person would rivet, one would stand on the other side as a bucker.

Louise’s year-and-a-half in manufacturing came to an end suddenly, but not because the war was over.

My boyfriend found how he could get leave from the Navy if we got married. [So] I left work at the plant, and five days later we got married.

Just out of high school, Wilma Foster went to work as a riveter on the wings of PT-19s, and she did it to support her brothers who were in the Navy. Her brother told her about an airplane being built in Hagerstown, Maryland, and off she went.

When the war was over, the boys that worked — of course they came back for their jobs. I had been away from home for four years and I wanted to go home. When I got home, I met my husband, and we got married when we knew each other just a little while. And it lasted forever!