On the weekend following the presidential election, some people sought comfort and understanding. The Bitter Southerner had a notion we might find those things in a small town in southern Georgia, so that’s where we went: the Sunday school class taught by President Jimmy Carter at little Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains. This is what we heard and saw on November 13, 2016.

Story by Jennifer Crossley Howard | Photographs by Johnathon Kelso

The path to Plains, Georgia, in November is lined with barren cotton fields, harvested before a mean drought began plaguing the Southeast, draining the inlets of great rivers and spreading cracks through the red clay earth.

The small wildfires I passed along I-65 South, my route from North Alabama toward South Georgia, seemed to symbolize the surprise of a bitter election and possibly a foreboding of what is to come.

But it appeared the road to Plains was also sodden with hope. Americans as varied in background as a lifelong Democrat and a former aide to George W. Bush flocked here on the Sunday after Americans made Donald Trump their president-elect. When Jimmy Carter first ran for president in 1976, he invited curious reporters to his Sunday school class to learn more about what having an evangelical Christian as president would entail. Forty years later, they pack the pews every time he is in town to teach. This Sunday, visitors arrived before 6 a.m. at Maranatha Baptist Church to get a seat in the sanctuary for Carter’s 10 a.m. class. Many said they came to find some sort of sanity and faith after a bleak week. They shivered and took pictures in front of the simple brick church in a pecan orchard. Portable bathrooms and a small playground helped them pass time until they could go inside.

Inez Haynie Dodson of Baltimore traveled to Plains with her daughter, Sharon, to kick an item off Inez’s bucket list.

“He’s such a great humanitarian, and he and Ms. Carter, I feel like, live the gospel,” Dodson says. “That’s what endears me most to them.”

She planned her visit well before the presidential election, but the timing had its benefits.

“Being here makes me not think about it,” Dodson says.

Robert Martin worked in Washington on the staff of President George W. Bush. He made the trip to Plains from Dallas because he has always been intrigued by Carter’s faith.

“President Carter is one who, both while serving and after, has a solid faith in God and his word,” Martin says. “And that’s a rare thing these days.”

Martin’s thoughts on the election were similar to those of many others who came to Plains: “What’s coming next? Nobody really knows what to expect.”

When you pull into the parking lot at Maranatha, you’re given a number, and when Jan Williams, the church pianist, calls out your number, you’d better listen and step in line. That secures your spot in the sanctuary. The overflow crowd has to watch Carter on a TV in another room. She warns women to put their “pocketbooks” in the car if they don’t want them in a photo with the Carters after the worship service.

Before congregants enter the church, Secret Service agents, who scoped the property well before dawn, check cell phones and Bible covers. One at a time, they examine worshippers, as they raise their arms and turn around.

James Earl Carter Jr., the 39th president of the United States, is neither typical nor predictable. He is an evangelical Christian who believes in separation of church and state. He said he believes Jesus would support same-sex marriage. A peacemaking former politician. A Sunday school teacher who gave Playboy an interview. A peanut farmer who became president.

Carter, 92, and his wife, Rosalynn Carter, 89, today keep one foot in politics and another in humanitarian deeds — and manage to do so in a way that gains respect and admiration.

Kim Fuller walks to the front of the church in a ruffled-collar dress and gives what she calls orientation.

“We’re so glad you’re here,” she says, and smiles, and you believe her.

When President Carter — that’s the correct reference — enters the room, do not clap, she says. We are, after all, here to worship God. And Mrs. Carter’s name is pronounced Rose-a-lynn, not Rah-sa-lynn, though she’d never correct you, Fuller assures us.

Members of the military should stand and remain upright until President Carter relieves them. This is the rule, even if you are family hanging out with Jimmy. Fuller recalled an episode in the 1970s, when her husband and brother-in-law stood for their commander-in-chief in a rather informal setting. “What were they doing?” she pauses and frowns. “What they were doing was drinking beer at Billy Carter’s service station.”

Everyone laughs, partly because they are nervous and partly because they are trying to stay awake. And because hearing a Baptist woman spill a beer tale in front of the pulpit already makes this early morning well worth it.

Maranatha Baptist was born out of Plains Baptist Church, a white, wooden Carpenter Gothic beauty that sits down the street from its child. Maranatha can hold 276 worshippers when Carter is in town to spread the gospel. It gets about 50 congregants on other Sundays. The church will celebrate its 40th anniversary next year, and Carter joined it when he returned home from Washington in 1981. Plains Baptist, Carter’s home church, was a member of the Southern Baptist Convention, and Maranatha began partly to start anew as a Cooperative Baptist Fellowship congregation because, unlike the SBC, the CBF supports the role of women in ministry and leadership positions. Carter published a letter in 2000 explaining his need to disassociate himself from the Southern Baptist Convention. The news even made Gloria Steinem’s Ms. magazine. He told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution the same year: “I personally feel the Bible says all people are equal in the eyes of God. I personally feel that women should play an absolutely equal role in service of Christ in the church.”

Virginia Applebaum and her daughter, Hannah, drove to Plains from Calera, Alabama. They said they were on a “Democrat all-star tour,” also seeing Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s retreat in Warm Springs.

“I’m a lifelong Democrat,” Virginia Applebaum says. “FDR is the gold standard for that.”

Carter, she says, represents the best that Democrats have to offer.

“President Carter is just an amazing, very kind, very good man, and after this election, I just needed to get my mind right,” Applebaum says.

Someone told her the Carters still Iive in the house they built in the 1960s.

“He had all the trappings of power and privilege, and he is the person he always was,” Applebaum says.

Plains is where the Carters were born, where they met and where they live, a few miles from where Jimmy Carter grew up on his father’s sharecropper farm. There, he played with black children, and Carter’s mother, Lillian, a pistol of a woman and a forward thinker, invited those children’s parents into her home. “Miss Lillian” worked as a nurse and generally ignored the laws of segregation. Her son inherited her verve and conviction, and rewrapped it in a wide smile and quiet charm.

There are a few Trump/Pence campaign signs just inside the Sumter County lines, but residents still seem to appreciate that one of their own, a Democrat and peanut farmer, made it to the White House. “Back the Blue” signs prick the front yards in Plains, alongside “Jimmy Carter for Cancer Survivor.” Last December, Carter declared he was cancer free.

Inside the sanctuary, Kim Fuller says Carter’s boyhood farm, part of the Jimmy Carter National Historic Site, just received four new Spanish goats, one named Brother Billy, for Carter’s colorful younger brother. Congregants whisper about the quaint sanctuary with mint green walls.

“Same paint as Grandma’s.”

“Same carpet as Grandma’s.”

Fuller passes two wood offering plates that President Carter carved, his initials “JC” on the back. In addition to winning the presidency and the Nobel Peace Prize and being a student of the Holy Bible, the man also, it turns out, dabbles in woodwork. Fuller points to a cross hanging behind her. He made that, too.

Balaji and Manjula Puttagunta of Newcastle upon Tyne, England, remember when Carter visited their city in 1977. Manjula was in high school, and when she heard Carter was in town, she ran down the sidewalk, only to see his hand waving from a departing car.

“She came here today to see the rest of him,” her husband says.

Later, he is serious. “People talk about a national treasure?” Balaji asks rhetorically. “He is a global treasure.”

The Puttaguntas admire Carter’s “forgiving nature and global view of concerns.”

To be fair, many view Carter as a one-term president who did far more good after 1981 than he did while in office. John Jalocha, a former Chicagoan dressed in a fedora and leather for the 45-degree fall morning in Plains, disagrees.

“It’s funny, I talk to people in the South, and they’ll tell me they think Jimmy Carter is a great man and a horrible president,” he says. “I tell them that’s basically how I felt about Reagan. I think they’ve got it backward.”

Jalocha says he wasn’t surprised Hillary Clinton lost.

“The Democratic Party is always trying to educate, and the GOP tries to sell.” He throws his hands in the air. “When you vote, you’re buying.”

Around 9:30, the Rev. Jeremy Shoulta comes to chat with the congregation. This Sunday is his last at the church, before moving to shepherd another congregation in North Carolina. President Carter has always been supportive of him, Shoulta says, but he was intimidated at first to take to the pulpit after a president.

“I’ll admit the first couple of times, it was tough to preach and look down and see that person sitting there,” he says.

The population of Plains is around 700, Shoulta explains, and its largest industries are peanut farming and tourism, both paths that lead to Carter.

Shoulta walks out, and moments later, Jimmy Carter walks slowly to the front of the church wearing a gray suit and turquoise bolo tie.

“I know you’ll be asleep before I get through,” he says, in that accent that is as familiar as a grandparent’s voice.

He asks where everyone is from, and as instructed, they call out a state or country, never the same one twice.

“Washington, D.C.?” he repeats. “I used to live there.”

He smiles the signature grin that launched a thousand caricatures, and visitors laugh in delight.

A few moments later, Carter says this crowd is lucky because the last few lessons were on tithing. He’s covering the Book of Revelation this month.

“I think it tied in quite well with the election this week,” he said, pulling more punch-drunk laughter from the congregation.

He gets down to it. Donald Trump won a “fair and square honest election,” Carter says.

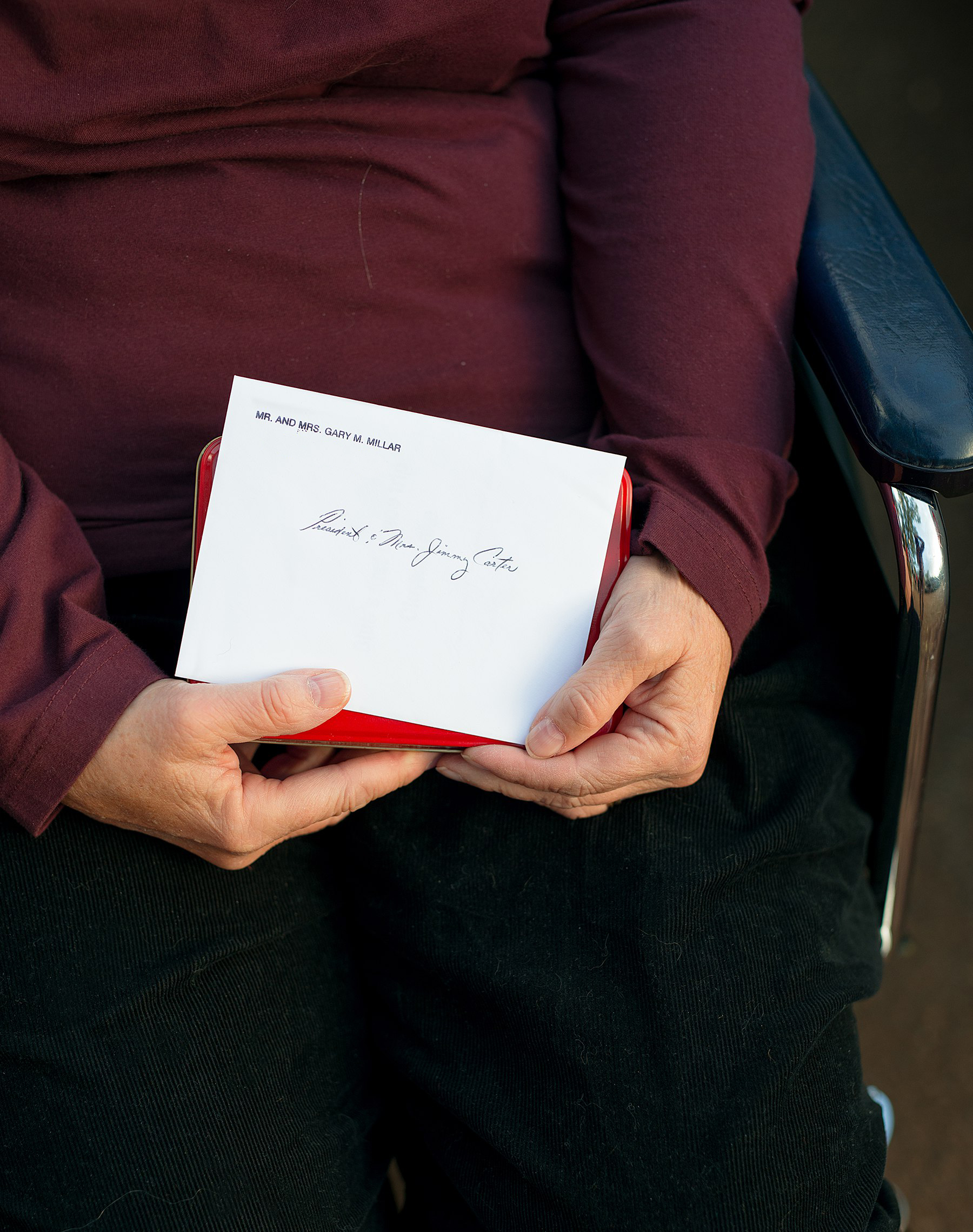

He called Trump first to congratulate him, and then he called Clinton.

“I was highly qualified to make both phone calls,” Carter quips. More laughter.

Carter endorsed Barack Obama in 2008, when he ran against Hillary Clinton in the Democratic primary. In a video shown at the Democratic National Convention this year, he questioned whether Trump’s morals and ethics match those of this nation’s founding. He endorsed Clinton.

He hopes the country will support Trump, he says. He adds that he spoke recently at Emory University in Atlanta about the politics of inequality, and that white, middle-class workers felt they have been treated unfairly. The Carter Center, the nonpartisan nonprofit the Carters started in 1982, just completed a six-month study of human rights. The center, which advocates for peaceful elections, negotiations and healthcare worldwide, assumes the most basic human right is peace.

“We need to make sure we pray for our incumbent, for Obama, until he leaves and for President-elect Trump,” Carter says.

Now, it’s time for church.

“I have very hard time understanding Revelation,” Carter says, pacing in front of the church. He will stand, slightly stooped, the duration of the 45-minute lesson.

He asks if anyone knows why there is so much symbolism in the book.

John was in prison, someone calls out, and he was speaking in a code to other Christians to avoid further persecution.

Carter goes through Chapters 6 and 7, and then asks, “How do you look upon worship?”

Silence.

Carter recalls Soren Kierkegaard, the philosopher and theologian, who was critical of the Church of Denmark because the government supports it. He also cites Kierkegaard’s belief that Danish churchgoers had an improper attitude toward worship: They came for their own entertainment, placing themselves in the role of audience members, when God should be the audience for their worship.

“We all think about what life would be like if it was perfect, pure,” he adds. The idea of purity is at the center of Christianity, Buddhism and Islam, he points out.

“What do we envision for a perfect future?” Carter asks. “What am I going to do about it?”

There’s a knock on the door to the sanctuary. Carter smiles.

“Are you thinking about it?” Carter asks. “God gave every person life and freedom to choose: What am I going to do to create a world close to perfect? We make these decisions hundreds of times every day.”

He continues: “I’m sure everyone who voted in the election last week feels they were right, and the others were wrong. We can choose to love one another. I think loving one another is the essence of Christianity.” Jesus, Carter points out, surrounded himself with the unlovable. He exemplified love “in an agape way,” Carter says. “Loving people who don’t love us back. Loving people who are different from us, loving people who are unlovable.

“It’s not easy to love someone who doesn’t love you back. We have a perfect example to follow if we want to. We have to decide individually. It sounds pretty simple, and it is!” Carter’s voice raises, then he finishes:

“There’s no tricks in it.”

We bow our heads to pray.