This Man Is an Island

David Wolkowsky returned to his childhood home of Key West, Florida, in 1962, when he was in his 40s. Today, as he nears 100, he has long been known as Mr. Key West. Michael Adno tells us how the island we know today became a reflection of one man’s campy sense of style.

Story & photographs by Michael Adno

Archival photographs courtesy of Lawson Little, Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, & David Wolkowsky

Close to midday in the middle of July, I edge toward the last block of Flagler Avenue on the fringe of the hive-like bungalows of Old Town Key West, near Higgs Beach. Only a few blocks off the water, the steady trade winds make the palms and poincianas whir and bend. Looking south, the sky holds a taupe blue that bleeds into a dark gray further west. To the east, the sun hangs high, its light making everything look postcard tropical.

I’m headed to the home of a man whose name every local knows: David Wolkowsky.

A street named after Wolkowsky (photo by Michael Adno) and David Wolkowsky just off Mallory Square with the Mercedes given to him by John Hersey (photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders).

When I reach his house, Wolkowsky tells me he returned home to Key West 56 years ago, in 1962. “It was literally a village. It was still like that,” he says, pointing to a large photograph of men clad in U.S. Navy garb crowded into a bar.

“There were remnants of the war, and they were trying to keep the Cubans out,” he says. “They had wiring around the beach to protect against a Cuban invasion.”

The big photograph sits on a counter, leaning against a bookshelf filled with biographies and monographs sandwiched between Indonesian shutters. From a couch in the center of the space, four wooden columns stretch upward toward high ceilings, and a thin sliver of a skylight stakes the perimeter. On the ground, sculptures, paintings, and orchids creep up to tables. Countertops are strewn with mementos Wolkowsky had collected. A note to Wolkowsky from Buckminster Fuller hangs below an Isamu Noguchi model. Leaning against an archaic Greek sculpture is a portrait of Wolkowsky drawn by the playwright Tennessee Williams. The words, “L’in Connu: C’est les yeux” — “the unknown: it’s the eyes” — are scrawled across it.

Portrait of David Wolkowsky by Tennessee Williams and a lime tree on Key West. (Photographs by Michael Adno)

Wolkowksy, 98, is most commonly referred to as Mr. Key West. In the 1960s, he developed the Old Town portion of Key West, which ultimately led to its ascension as a tourist destination. As a native, Wolkowsky set out to “preserve the past by making it work for the present at a profit,” he told a Miami Herald reporter in 1969, not long after opening his landmark project, the Pier House Motel, in 1967.

Today, much of what locals call “the rock” lies under the weight of development, yet when you wander around Old Town, almost every other home bears a Historic Register plaque, and the sky remains big and open. Much of that charm is due to Wolkowsky, maybe the town’s most celebrated yet most mysterious proponent, who was undoubtedly a catalyst for its rich melange of cultures.

Where the Overseas Highway stretches across 120 miles of contiguous islets and islands, the 6-square-mile island of Key West punctuates its terminus. To most, the tiny blip of limestone is known for the arterial vein of debauchery known as Duval Street, which some misguidedly compare to Bourbon Street in New Orleans. But between the franchise bars and frozen daiquiris and T-shirt shops, little portals lead through flora-laden haunts to the Key West that has drawn so many people over time. For some, it’s served as an outpost of solitude, to dry out, to feel less strange. To others, it’s been a dead end, a place to reinvent oneself, maybe a place to disappear. That’s to say the place casts a spell on people.

Its striated layers of codes, milieu, and history are part of what’s made the place so attractive — the gloss of its celebrity past, too. But even today with the influx of cruise-ships and Segway tours, ballooning rents and shadows of eras long-gone, the allure remains. If there was one way to put it, Key West exceeds your expectations — again and again. For me, it’s only grown more mysterious with each visit.

Meeting David Wolkowsky only deepened that.

When I arrive at his house, I pass through a hand-carved wooden door and through a courtyard littered with orchids, following one of Wolkowsky’s staff, Marcia, up a staircase inside. The periodic buzz of an oxygen machine fills the airy, open space, and my eyes begin to dart all over. Wolkowsky emerges from his bedroom in a loose-fitting, blue oxford shirt, pink pilled shorts, and slippers — his hair tucked behind his ears.

“I retired in 1962 and came back here, because my father died,” he told me. “Sloppy Joes and Captain Tony’s bar was condemned, so then I restored it. And here I am with my nudes.” He grins and eyes an oil painting propped up on the coffee table — an unclothed Tilda Swinton painted by her partner, Sandro Kopp. Then, he points out a model of Ernest Hemingway’s boat, The Pilar, in a plexiglass vitrine.

“And you still have to pay to get on the Conch Train,” he tells me, referring to the longstanding local history tour on wheels.

Of all the things in his home — which some call the David Wolkowsky Museum of Art — one work seems centripetal. Positioned on a table facing the couch we sit on, a painting of Duval Street storefronts stares back at us. The work is a low-relief carving with its surface painted in a simple yet meticulous fashion by Mario Sanchez, titled “Golden Era.” On the right side, a dim lamp’s glow highlights Sanchez’s rendition of Wolkowsky’s grandfather’s store in Key West, which reads “Wolkowsky & Sons Clothiers.”

Every time Wolkowsky talks about that piece, his friend Cori Convertito, a curator at the Key West Art & Historical Society, tells me, “he lights up.”

“Golden Era,” by Mario Sanchez (1908-2005), Oil on wood, 16.5 x 33.25 inches, 1975, Courtesy of David Wolkowsky

“Three generations back to panhandling,” Wolkowsky says as he begins to tell his family’s story. “My grandfather came to New York then Jacksonville and gravitated to Key West in 1880 almost penniless. Then, he saved enough to buy a small store.” His grandfather, Abraham Wolkowsky, came to America from Russia and slowly made his way to Key West, where he opened a small mercantile store, selling mostly men’s clothing, and his wife opened an adjoining store selling fabrics shortly after.

“They limped along financially when they got here,” Wolkowsky says.

Suddenly, he asks to be excused to “follow up on something.” As he pulls out his iPad, he encourages me to wander around.

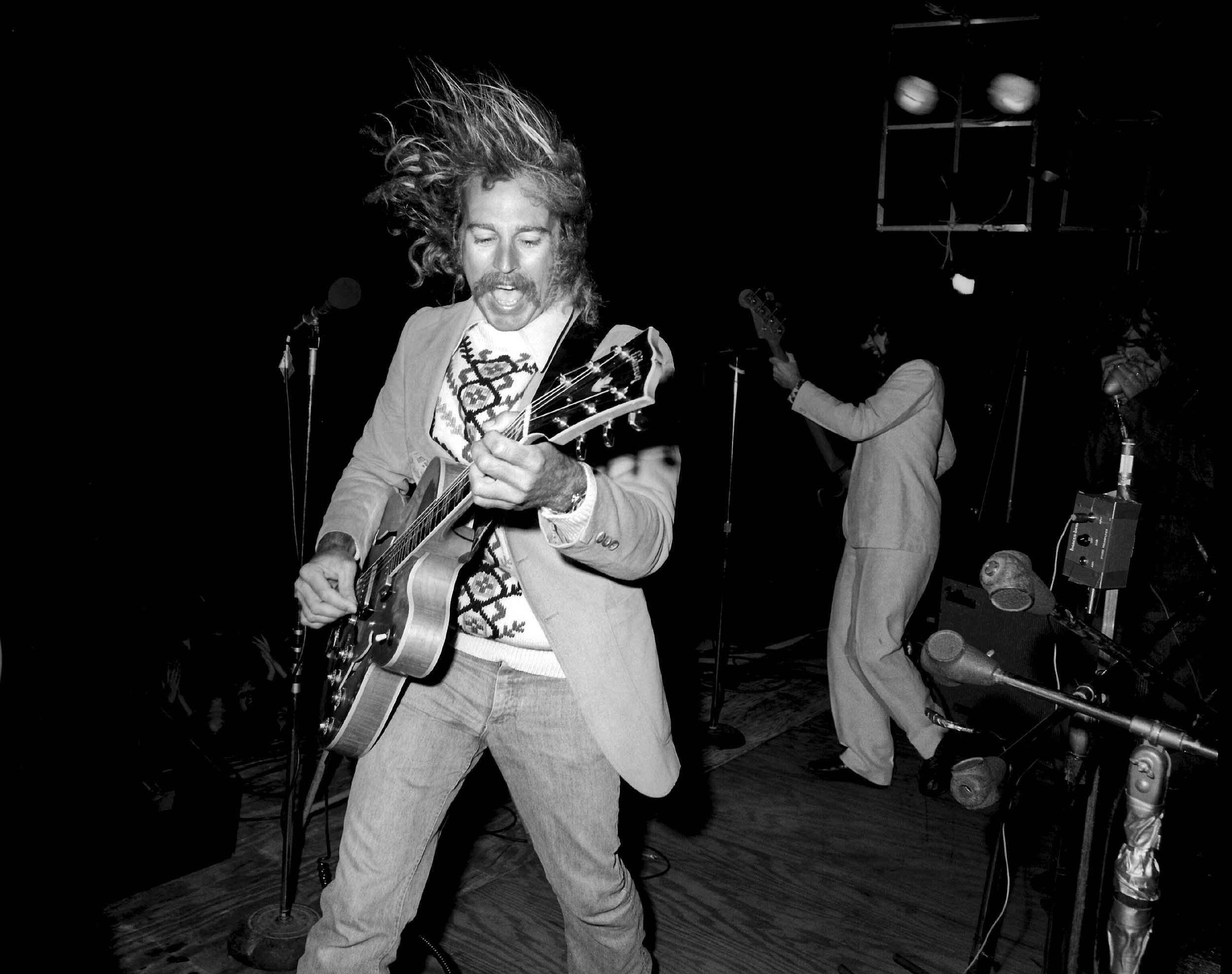

Moving around the living room, faux master paintings hang next to modern prints — Miro, Copley, Matisse. Mementos of projects past, press clippings, and letters adorned the walls — spilling onto tables interspersed with photographs and piles of books. High and low become indistinguishable. On one table lined with small, framed photographs, Wolkowsky’s indelible grin turns up in images of countless celebrities and artistic pillars of the South. There is Jimmy Buffett, who played for drinks and performed his first paid gigs at the Pier House’s bar, the Chart Room. There is Truman Capote, whom Wolkowsky lent a double-wide trailer on the Pier House property, and it was there Capote penned his final novel, “Answered Prayers,” although he never finished it.

Jimmy Buffett and the Coral Reefers playing at Mallory Square in Key West, 1977. (Photographs by Lawson Little)

Passing by a menorah nearly my size — a piece Wolkowsky acquired from a demolished theater in East London — he asked, “Do you like the menorah? Or is it too Yiddish for you?”

Picking up his story again, he explains that in 1923, when he was 4, hard times reached Key West, and his family moved to Miami — then a new town.

“We lived on the bay at 21st Street. It’s now a hotel,” he says. “When we moved there, it was the most anti-Semitic city in the world. Jews were always looked at a little oddly.” He remembers attending “Ms. Cushman’s school with the newly rich.” On 19th Street, the family attended a Reform temple. “My father wasn’t religious, but my mother had tried to emulate her mother — tried keeping kosher,” he says. “My father went along with it, but he would still get a crate of stone crab.”

As to Wolkowsky’s faith, an old friend of his explains he did not think Wolkowsky was religious, but he had noticed frequent visits from a rabbi. When he asked Wolkowsky why, Wolkowsky simply said, “Gelt.”

Of his mother, he tells me, “She was a Yankee, and like all good Jewish mothers, she wanted me to be a doctor.” Later, Wolkowsky found himself on a pre-med track at the University of Pennsylvania where he realized, “I wasn’t cut out to be a doctor; I was cut out to see a doctor.”

He remembers visiting one of the plentiful Jewish fraternities at Penn.

“I brought my bag, but I wasn’t particularly enchanted, so I moved into the dormitory,” he recalls. “There, I became busy with debutante parties, which changed my outlook, and now I’m back to being basic on my own time,” throwing his head back and cackling. “I got interested in architecture, and then I graduated in 1943.” After four years in the Merchant Marine, he ended up in New York City.

“I wasn’t very good at my job, so I moved to Philadelphia,” he says. “I started doing over little slums, broken down little alleys that are now the place to be.”

In the 1950s, Wolkowsky (who went by his middle name, Williams, because “it was simpler”) began restoring the outer ring of Rittenhouse Square in Center City, Philadelphia — little streets and alleys with two- or three-story buildings with no plumbing, the homes of servants.

“I started very gradually,” he says. “People all took trains out to apartments and houses on the main line then, and I coaxed them into living in Center City.” He remembers buying homes for as little as $100, “but the houses were in deplorable states.” And in March of 1955, with a few projects in the rear-view, Wolkowsky was named the Man of the Month by Town & Country magazine in March 1955 for his work in restoring the forlorn but historic center of Philadelphia — a city which today boasts more than 600 National Historic Register sites.

A few years later, he set in on his hometown — Key West.

Key West’s vernacular architecture in Old Town. (Photograph by Lawson Little)

First, Wolkowsky rescued Sloppy Joes — formerly further down Greene Street but later moved to its current location at the corner of Greene and Duval, The original location bears the name Captain Tony’s — after another eccentric from the end of the road, Tony Tarracino. Shortly after, Wolkowsky began buying swaths of Key West, moving homes to the lower portion of Duval Street. Then he purchased the original cigar factory, the Cuban ferry docks adjacent to what is now Mallory Square, and then finally, he began the Pier House, which he hired Yiannis B. Antonidis to design. Renee d’Harnoncourt, former director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, deemed it the “most unusual motel design in America.”

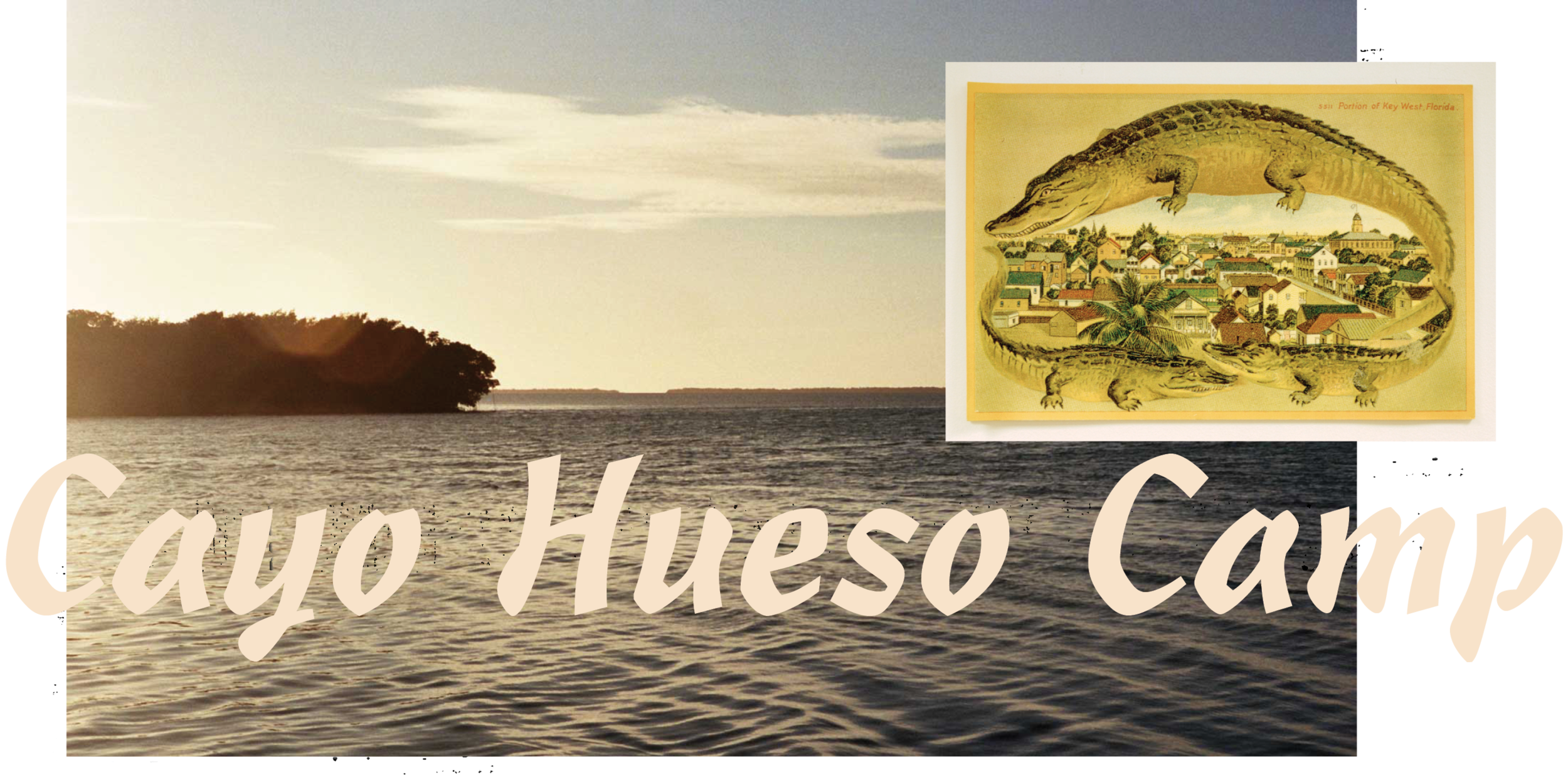

Long before 1962, as polar caps reformed in the Pleistocene Age, the coral forest skirting the edge of the Florida shelf peered above the ocean’s surface. Soon, lifeforms propagated along the chain of islets all the way down to Key West, which was deemed Cayo Hueso by Spanish explorers. In 1776, the first recorded mention of “Key” was adorned to the place. Except for Native Americans, the place remained uncolonized; the occasional seafarers would come ashore in search of fresh water, but otherwise the place was wild and uninhabited. Then, in 1821, when Florida became a U.S. territory, Key West was settled due to its natural deep-water port, and the city developed rapidly. In its first 40 years, the population grew from 500 to 5,000, subsisting on wrecking (ship salvaging), trade, and the promise of a burgeoning military economy.

Although Florida was a Confederate state, Key West became a strategic Union stronghold during the Civil War. So, while much of the South disintegrated following the war, Key West remained intact, which led to it becoming the largest city in Florida at the turn of the 20th century. Plus, its proximity to Havana buoyed the town as a trading outpost.

In the 20th century, the railroad arrived along with sea planes and 42 bridges that connected Key West to the mainland. Mile Zero became accessible. Piracy and wrecking molted into shrimping and the first signs of tourism. With World War II, Key West’s military infrastructure swelled, eventually receding after the Cuban Missile Crisis. And with its ebb, Key West’s shift from an economy based on the military gave way to its tourism economy, although nobody would have been so bold as to predict that change — save Mr. Key West.

Two things followed Wolkowsky to the end of the road in 1962: his sense of preservation and the inextricable ingredient that has lent Key West its ineffable charm — camp. Fortunately, both have remained extant.

When I go to Wolkowsky’s for lunch another day, we watch a film together. Before I come, he warns me to “throw the pen away.”

On a couch in his bedroom, we watch “Call Me Madam,” an Irving Berlin musical from 1953 starring Ethel Merman. Wolkowsky loves it. After one of his favorite scenes, where the young press attaché (Donald O’Connor) approaches Princess Maria (Vera Ellen) while perusing a record shop in song and dance, Wolkowsky tells me the story of how he came to know the word: “camp.”

At a party in Philadelphia while Wolkowsky was still a student, he recognized Lucien Beebe, the bicoastal polymath who had started Nevada’s first newspaper. Beebe approached, and “I just handed him my drink,” Wolkowsky tells me. Beebe laughed and replied, “You’re such a camp.” That was the first mention, the flowering, the thread of solidarity that has stuck with Wolkowsky since.

“Michael, the most important thing is camp,” he tells me. “Very few people have it.” He assures me I have it — “but not completely.”

Pausing the movie, we parse the idea of camp — pulling up websites, laying books on their spines, running through examples to ask: What is camp? Or, more specifically, how do we articulate Wolkowsky’s idea of camp?

He agrees with some denotations we find online — theatrical mannerisms, exaggerated humor, a mingling of high and low that challenges the status quo in art. Of course, as many have tried, the word, its sensibilities, and its proxies have remained elusive and difficult to pin down. But camp is as plain as day in Wolkowsky’s home, with its faux paintings that are nearly indiscernible from the real things, the levity with which he addresses all things, his coded language.

In the town, itself, camp seems essential to Key West’s sense of place. While Susan Sontag was heavily criticized for her explication of the word as a sensibility, as a style, she put it well when she wrote in 1964, “Camp is esoteric — something of a private code. To talk about camp is therefore to betray it.” In other words, depending on where and when or with whom, the word holds different meanings, evading classification for decades, maybe deliberately. And while increasingly difficult to articulate, Key West’s brand of camp reflects Wolkowsky’s understanding — never on the nose, always sideways, a place where anonymity feels like an innate right.

We talk about the merit of being concurrently campy and professional.

“You have to be both,” Wolkowsky stresses as his voice takes a lower register. Marcia walks by us with yellow latex gloves on, and he smirks. “Get a picture,” he says. Then, we all break into a mock fashion show, laughing and striking poses in a triangle.

Wolkowsky kvetches about most of the stories written about him in the past, dismisses them with a wave of his hand.

“I’ve been through the paper mills, and in the end, it’ll all end up in a diamond waste paper-basket,” he says. He takes a breath, his smile returns, and he adds, “But I appreciate good trash.”

David Wolkowsky (right) and Sir Richard Shepherd on the roof deck of the Duval Street apartment.

On the roof of the Kress building in the heart of Duval Street, next to the San Carlos Institute and directly above Margaritaville, is Wolkowsky’s downtown apartment, a penthouse of sorts. If you look up from Duval, modern facades climb up for three stories, and then you see just a sliver of a weathered, wooden balcony poking out, seemingly out of place. Each year after the first day of the Key West West Literary Seminar ends, poets, writers, and historians file into this space via a tiny passenger elevator that has become legendary for its malfunctions.

Annually, Wolkowsky hosts a party here for invited writers — in a building he sold to Jimmy Buffett while retaining lifetime rights to the penthouse apartment and rooftop. It has an air of alchemy inside. Large-format cameras sit dormant on tripods. There are enough books to fill municipal libraries, dynamic arrangements of furniture, photographs of Key West in the 1960s, and faux master paintings like “The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries.”

His longtime friend Phyllis Rose, an author who has lived in Key West since the early 1990s, points out that all his homes — his house on Ballast Key, his apartment on Duval Street, and even the rental homes he owns — brim with books. On bowed shelves, in neat stacks, everywhere.

During the 2017 party, I quietly scanned the room, looked out through the sliding glass doors, over the top of Key West’s flora-laden haunts with nothing to break my line of sight, and became fascinated with the apartment’s owner, David Wolkowsky.

That’s where I fell down the rabbit hole of Key West.

The phone rings, and Wolkowsky’s eyes widen.

“It could be the sheriff,” he quips. “We might have to hide you in some orchids.” On the phone is a woman from Books & Books, an independent bookstore in town, telling Wolkowsky his copy of Marlene Dietrich’s biography has arrived. He asks her to order another copy along with David J. Garrow’s “Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama,” for Marcia.

In February 2016, Key West’s Books & Books opened under the supervision of the renowned children’s fiction writer Judy Blume, her husband George Cooper, and founder Mitchell Kaplan — it was the chain’s ninth location. In the early 1990s, Blume needed a place to finish a book. It was winter in New York, and she craved warmth. Wolkowsky’s friend Phyllis Rose was then a recent transplant to Key West, and she suggested Blume finish her book there.

“We rented a house sight unseen,” Blume tells me. “It turned out that it was a house owned by David.” When she and Cooper arrived, Wolkowsky was there to welcome them, and afterward, he took them in.

“I’m here 22 years later, and that’s because of David Wolkowsky,” Blume says.

During the summer, squalls pass over the thin blip of land between the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico, showering Key West almost every afternoon. Those squalls often turn into thunderstorms that send dogs scurrying into corners come 3 p.m. Blume likens herself to those dogs because she suffers from astraphobia — the fear of thunder and lightning. Once during a storm, Wolkowsky, who visits the store nearly once a week, pulled up outside as thunder groaned. His driver came inside to let Blume know Wolkowsky wanted to show her something in the car. Afraid to leave the tiny inner office, let alone venture outside, Blume apologized and told the driver she’d come see Wolkowsky at home once the storm passed. The next thing Blume knew, Wolkowsky was out of the car and braving the downpour to pass through the double doors of the bookstore. Inside, he sat down and told her, “I want to show you something.” Slowly, he unwrapped a photograph of Olivia De Havilland holding a painting he had commissioned for her 100th birthday — a painting by a local artist, Susan Sugar, of his home on Ballast Key.

“Only David,” Blume says, glowing.

David Wolkowsky with the bones of the Pier House Motel being assembled at the west end of Duval Street. (Photo courtesy of David Wolkowsky)

To her point, Wolkowsky’s Ballast Key home might be most illustrative of who the man is. Eight miles west of Key West, across the Northwest Channel and the greater portion of 200,000 acres of flats, basins, and cuts that make up the area known as The Lakes, lies Ballast Key — Wolkowsky’s private island. While the corner of Whitehead and South streets in Key West boast the title of southernmost point of the continental U.S., Ballast Key is actually the southernmost point in the contiguous U.S. Out there, where the water quickly falls off into the straits, it feels like the end of the world.

“The locals used to go out there and picnic,” Wolkowsky says. “They’d cook a hot dog over burning trees.”

Views of Ballast Key, courtesy of State Archives of Florida, Timothy Greenfield-Sanders and David Wolkowsky.

As to how he bought the island, which once belonged to the U.S. Navy, he says, “I called the owner, who was in Central America, and I spent years negotiating with him. Finally, he agreed to sell me half the island, but I told him that I couldn’t deal with that.” Then, in 1974, Ballast finally became his.

Over the following years, Wolkowsky built his home on the island’s southern edge, assembling his “big metal shack” on land and schlepping each piece out bit by bit. The four-bedroom home on Ballast is based on the Northwest Channel lighthouse, known as the “Hemingway Stilts,” that burned in 1971. Wolkowsky’s nephew, Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, a prominent photographer and filmmaker, calls it “a simple little family retreat — eight miles off Key West.”

He adds, “It has tremendous sensibility to it.”

When Wolkowsky began building, Ballast Key was barren. As Rose tells me, “He put every single tree on that island,” along with plumbing, desalination tanks, and a 550-foot dock. “He is indomitable,” she says. But when I ask Wolkowsky what’s out there, he replies, “Just mangroves.”

Then, he adds with a smile, “I brought cashmere to Ballast Key.”

Out at Ballast, Wolkowksy has hosted guests from Truman Capote to Margaret Thatcher. He still — to this day — serves his most revered guests wine, potato chips, and hot dogs.

“Key West is always on his mind,” Rose explains, and whenever someone comes to visit, he thinks of how that can be used to advance the reputation of Key West. Like his nephew explains, “He brought a lot of important people there. He made it into more of a winter retreat than it ever had been. I think we forget all that with the cruise ships, the Conch Train, and the bicycles everywhere, but the buildings they’re there to look at are there because of David Wolkowsky.”

He would never mention the award, but in 2001, Wolkowsky endowed the Teacher Merit Awards, which give nine teachers individual grants, totaling $65,000 annually. Despite his modesty, you can tell it’s one of the things he’s most proud of.

“He does a lot of behind-the-scenes work that he’s not recognized for,” Convertito tells me. “He makes contacts and brings donors in.” Simply, he does the legwork that’s become invaluable to Key West’s art community and its history.

Fortunately, that good faith has extended to local businesses, events like the Key West Literary Seminar, as well as individual artists and writers.

“David is one of the few people who understands that the best way to support artists is by buying their work,” Rose says. “You can have all the institutions, fellowships, and grants that you want, but the best way to support an artist is to buy their work, and David has always done that. There’s a clarity of mind about him that’s so wonderful.”

Caroline Street in Key West and Wolkowsky showing photographs of when his home on Ballast Key was being built. (Photographs by Michael Adno)

Scanning the walls of his home together, Wolkowsky and I arrive on a painting of Key West’s inimitable sky — those soft clouds reflecting brilliant hues of pink and amber that tend to appear nearly each day here. He told me it was by the best artist in town, Susan Sugar. And he immediately dials Sugar and invites her over. In 20 minutes, she arrives clad in a sundress and hat. Warmly, she greets Wolkowsky, who introduces me as a “27-year-old Yohoodum” checking to see how Jewish he is.

She asks him, “Who writes your scripts?”

Sugar — whose subjects for 14 years have been Key West’s sea and sky — met Wolkowsky through friends who suggested he have a studio visit with her.

“She married a house,” Wolkowsky says, referring to the Old Town bungalow she inherited from her late husband. Sugar, a New Yorker turned Key West transplant, remembers that after she first met Wolkowsky, he sent her a postcard that read: “Dear Susie, Hope New York is good. More vodka. More mink.”

As Rose tells me, “You can’t learn from anybody better than David. He really knows how to live.”

From the opening of the Pier House in 1967 alongside the reanimation of Duval Street, Old Town, Pirate’s Alley, The Reach, and a seemingly endless litany of projects, Key West took shape under Wolkowsky.

“Key West is his ongoing project,” Rose says. “It was literally a dump. There was nothing. He made the place by his vision and his charm as dispensed through the Pier House. And now, he continues to do that by entertaining people, celebrating them.” And that’s all to say, beyond just the physical architecture that hemmed the place in and gave life to the rock, Wolkowsky’s vision — to see what nobody else could have — transformed the terminus of the Overseas Highway from a sleepy, wartime hangover into a bustling, rich cultural destination. Rose says Wolkowsky understood the importance of style, and ultimately, she contends, “The whole of Key West is really founded on David’s style.”

His nephew says that “so much of David is his sense of style. He’s an artist in his own way. That comes through both in his personal life, the way he lives, the cars he drives, and the way he dresses. But also, you see it in the things he builds.”

I asked Wolkowsky what he sees in Key West today more than 55 years since his return. He chews on the question for a second.

“I see a charming town, but I don’t see the village I remember,” he finally says. “It’s professional charm now.” His checked brow straightens. The corner of his lips rise, and he looks toward the Sanchez painting of his grandfather’s store.

“I ruined it,” he says, and his bright laugh fills the house.

David Wolkowsky (left) and Sarah Benson, 2012. (Photograph by Nicholas Doll)

Later that night, family friend Jolly Benson reminisces about spending summers out at Ballast with Wolkowsky. On a spacious plot in Key West, we sit inside the heart of a behemoth banyan tree, its tendrils spilling out all around us. Illuminated by a chandelier hanging from the tree, Benson tells me how Wolkowsky planted a swath of palms on Ballast recently — noting by the time they reach maturity, most of us along with Wolkowsky will be gone. But like many of Wolkowsky’s contributions, it’ll take decades for us to truly register their meaning, to appreciate them wholly.

“I think the thing that David has done more than anything else is to keep Key West from becoming high rises,” Greenfield-Sanders says. “And while other people were a part of it, he was instrumental. You can’t build higher than 40 feet: That’s the legacy of David Wolkowsky.”

Something Wolkowsky had said to me a few days earlier came back to me with the trade winds rustling the banyan’s tendrils. He told me, with a grin, “Don’t let facts get in your way.” Then, more seriously, he added, “The world is made up of distortions that turn into fact.”

Just like the coral forests that climbed out of the sea during the Pleistocene Age, giving way to Key West as an outcrop of porous limestone, the town is now an adept register of David Wolkowsky’s sense of style. His spirit perforates the place, and his presence hangs over it — ever charming, ever David.

Michael Adno is a Florida-born writer and photographer. He last wrote for The Bitter Southerner in January 2018 about Ernest Mickler, his anthology "White Trash Cooking," and the effect AIDS had in rural Southern communities in "The Short & Brilliant Life of Ernest Matthew Mickler."