Wild Miles on the Big River

The Mississippi River is big, dangerous and industrialized. But from St. Louis down to the Louisiana bayous, more than 500 miles of the great American river remain wild. And you could have no better guide through the river’s ever-decreasing “wild miles” than John Ruskey.

From five miles upstream the boys spied the electrical lines, arcing over the river and buttressed by two sets of truss towers. But why would they care? The Mississippi River is wide. What are the chances you’d hit a little pylon?

Then they were 100 yards away, caught in fast water. They paddled hard, but their raft — ungainly, hand-built, their home for five months now — would not budge from its path. As it slammed against concrete, both boys fell. Supplies scattered, journals and a guitar and precious food disappearing into February water flowing cold and fast. The front of the raft began to ride up the pillar; the back slipped into the river. Then, snapping like a cracker, the raft came apart. Both boys plunged in.

One of those boys, John Ruskey, had always been drawn to water. There’s a story his family tells: At age 2, young John often stared out the window at the pond on the far side of his Colorado road. One day, unaccompanied and unannounced, he walked out the door, seeking the pond. As a first grader, his peers called him the Weatherman; a teacher phoned home because during a downpour he refused to come inside. When he graduated from prep school in 1982, Ruskey ventured to the Mississippi River.

He and a friend camped in Wisconsin, building a 12-by-24 foot raft from refuse and scrap wood. They floated south through winter, warming themselves alongside a fire built in a halved oil drum. They sipped coffee and played chess with pieces they’d carved from willow branches and watched America slip by.

Just past Memphis — one of the most memorable sights on the southern Mississippi according to Ruskey, shimmering on its bluff above the water — they noted and ignored the electrical lines. They resumed a game of chess.

Ruskey cannot piece together all that happened. He knows he went numb, and that he and his friend lashed together the pieces of wreckage they could grab. They heaved their chests out of the frigid water. As the sun slipped down, Ruskey was shivering, nearly catatonic, ready to let go of life. Given the cold water and their lack of precautions (Ruskey was not wearing neoprene, as he does now on cold days), he probably should have died.

He has written an account of the wreck. It serves as a kind of creation myth, an explanation of the man Ruskey has become. He describes his delirious exit from the industrial outskirts of Memphis and his arrival in a realm unimpaired by the toils of mankind. The boys washed up on Cat Island, just past the Mississippi border, where a flock of red-winged blackbirds was settling into the darkening woods.

He made a promise, to himself and to the river: If he survived the night, he would return to this beautiful place.

Thirty-three years later, John Ruskey is a quiet man. If you meet him in the street, he can seem removed, even standoffish; an interlocutor struggles to find the right questions to ask. He’s self-possessed, so much so that he seems bored, or maybe bewildered, by our workaday world.

Once, years after that crash, he found himself working an office job. Every afternoon he would get overwhelmed and claustrophobic, he’s said. “I had to get out,” he once told an interviewer. “I had to go.”

He would go to the Mississippi River.

If you see Ruskey there, on his river, you see a man come alive. His eyes sharpen. His posture loosens. He sings as he paddles. Every sight inspires a story — an abandoned house on stilts recalls an anecdote from Twain; the fog atop the river reminds of him being lost on the river at night. He shares his wisdom: ornithology, astronomy, physics, geology, navigation, more.

I’ve seen him perch in a drowned willow, floating down the river. When it came alongside his canoe, he scrambled out onto the limbs to investigate what detritus had been caught. Then, grinning, he rode the tree a half mile downstream.

Here, on the river that almost killed him, Ruskey found peace — and a career. He has almost certainly spent more hours paddling the Mississippi than anyone else alive. He leads custom river tours. He rents canoes and kayaks. He mentors low-income students, teaching them to build canoes and camp and serve as river guides. He paints watercolor interpretations of the river, which he hands out on his journeys as a way to introduce wary locals to the wilderness that flows through their backyard.

It took him years to get back to the river: wandering years.

“I was just a kid off the street,” Ruskey told me. “I had a backpack and a guitar.” He returned to Mississippi not to see the river but to learn the blues. For a while, that music sent him touring the world. But he would always come back to Mississippi, where that river ran relentlessly south. He could never stay away long.

Now he’s nearly completed what might be considered his life’s great work. “Rivergator,” it’s called, a document that when finished will be more than 1,000 pages long. It contains plenty of history, some lovely storytelling and lots of philosophical wisdom. But really it is a guide: Mile by mile, it leads readers down the Lower Mississippi River Water Trail, which, stretching from St. Louis to the Gulf of Mexico, will be the longest river-based water trail in the United States.

Somehow, he’s got to convince a nation that their beliefs about their iconic river are all wrong: that it’s not dirty, not dangerous — at least not too dangerous. That it’s exactly the place you want to be. First, though, he’s got to get to the water.

Ruskey naps, tucked between coolers and luggage in the trunk of an old Chevy Suburban. The truck barrels south through Mississippi darkness; a 33-foot wooden canoe, built by Ruskey, is strapped to a trailer behind us. It’s March 2015, one of those hazy hours before dawn. Somewhere before Vicksburg, Ruskey sits up. In Natchez, he pulls out his cell phone. This might be the best office space he’ll have for a week.

Ruskey woke today at 1 a.m. to load the canoe; for a week straight he’s been up each day before dawn, seeking a few quiet hours to work. A voyage like this requires a flurry of emails. He must consult maps and weather forecasts and compare the river levels at more than 20 gauges to predict its speed and how quickly it’s rising. It’s high enough right now that, according to the warnings Ruskey has included in “Rivergator,” paddlers should not be out.

Creeks and bogues slip past outside the truck windows, thin lines of water trickling into the woods. This is how Americans know their rivers, Ruskey often says. Even the famous Mississippi is, for most of us, just a glimmer of water through a guardrail as our car speeds over a bridge. Where Ruskey lives, in the Mississippi Delta, the big river is hidden behind levees, so that even those who live within a stone’s throw must make an effort to reach the water. That’s the way most want it, thanks to memories and legends from 100 years of devastating floods. (The most recent, in 2011, caused several billion dollars in damage). The ports of New Orleans and Memphis, where the river is most visible, stink of oil and fish. Many believe that the river is just a sewer for toxic waste.

Ruskey disagrees. He considers nearly two-thirds of the riverbank along this southern stretch of the Mississippi wild. Indeed, in this part of the Deep South, it is some of the only wilderness left.

Few see it. While more than 600 people summited Mount Everest last year and more than 700 through-hiked the Appalachian Trail, Ruskey believes only 50 paddled the length of the river.

In 1998, 16 years after the Coast Guard rescued him off Cat Island, Ruskey incorporated the Quapaw Canoe Company. Based in Clarksdale, Mississippi, it was the first wilderness outfitter along the Lower Mississippi. In 2011 he began compiling Rivergator. For four years, he’s led expeditions down a hundred miles of river at a time, ensuring the details are up to date. More than 900 miles of guidance are already available online; the project will be completed in late 2016. It is, Ruskey says, the culmination of more than 30 years of work.

Today begins the penultimate Rivergator expedition. Since the final journey will be down “Cancer Alley,” lined by heavy industry from Baton Rouge to the coast, this is Ruskey’s last voyage through his beloved “wild miles.”

But now, all his careful plans have gone awry. In Woodville, where the crew gathers at a gas-station café to fuel up on soul food and collect its final few members, Ruskey learns that the flooding has washed out the road to the boat ramp. It’s the only river access for miles.

There are eight of us: two journalists, two paying customers, a hired videographer, plus Ruskey and two trusted guides. Mark Peoples, who played pro football for the New York Giants, encountered Ruskey during one of his daily visits to the riverside in St. Louis, his hometown. Seeking a way to serve the river, Peoples was inspired by Ruskey’s passion. After a trial expedition with Quapaw, he moved to Clarksdale — into an old bar that sits above Ruskey’s office — and became a guide. Now everyone knows him as River. Braxton Braden, known as Brax, is retired after 20 years in the Navy. They call Ruskey John or Johnny or Driftwood Johnny.

Of this crew, I have the least experience on the big river: none at all. I’ve arranged to join the trip for its first three days. While everyone cinches shut dry-bags and tugs on boots and wetsuits, I watch to see how it’s done. The truck is backed up on a farm road that, a few feet beyond us, has been seized by the flood.

Such is the nature of rivers. They are not the stable, identifiable places to which we’re accustomed in the age of Google Maps. Change the zoom on Google’s satellite map, in fact, and you’ll see the river change. Different photos show different water levels, which vary up to 30 feet in a typical year. Dry land turns to back-channels; islands emerge from the water. Now this pasture has joined with the river system.

“We’re getting onto the biggest river in North America,” Ruskey says later, “and the only access in southern Mississippi is through a cow ditch.”

A snake skims across the surface of the ditch. Ruskey dives in, baptizing himself in scummy water.

We’ve been sent here by the mayor of Woodville, who heard that Ruskey was in town. He arrived at the café with a delegation of locals, who unfurled a surveyor’s map and pointed out a route: Paddle a few miles across this flooded field to the Buffalo River, then a few miles more to the Mississippi. Just one problem. This is private land. A phone call has assured our safe passage; down some of these dirt roads, Ruskey says, the locals aren’t too friendly.

We met our one-woman welcoming committee in Fort Adams, which, when New Orleans was foreign property, was the U.S. port of entry on the river. Now there’s little more than a one-room store that sells fishing supplies. Our contact, a middle-aged woman whose family farms nearby, stands in the dirt lot and squints at the canoe.

“That your idea of a good time?”

Though the sun is past its zenith, Ruskey does not rush. He chats with the locals, as he chats with everyone he meets, waging a slow campaign of hearts and minds. He gives a copy of the latest Rivergator poster, a reproduction of a watercolor map, to the storekeeper. An earlier edition is already tacked to a wall inside.

The Lower Mississippi is a big river, fed by the collected waters of many tributaries — the Missouri, the Ohio, its own headwaters in the Minnesota lakes. You could call it the real Mississippi, the place where the waters of the continent finally merge. The river basin drains portions of 31 states, from New York to Montana, over 40 percent of the continental U.S.

Controlling that water requires infrastructure. The woman at the store is fluent in its technical terms, and talks of spillways and the distribution of flow. She has clear opinions, too: The water floods here and not downstream, she says, because Louisiana farmers have more money and power. The U.S. government, which controls the river, cannot possibly keep everyone happy.

Another woman pulls into the lot, seeking gas at the empty pumps, and our host discloses the nature of our strange quest. River chats with this new arrival. As we drive away, he shares her story: She lost a son to the Mississippi. Fishing without a life jacket, he fell in, and was drowned by the weight of the water that rushed inside his boots.

Now, after a brief ceremony, we paddle out. What is usually a hunting club is hidden beneath five feet of flat backwater. Birds of prey sit watchful in the treetops; colonies of fire ants have linked their legs to form a fabric that floats on the water and shimmers as they move their legs. The natural world thrives in this flood.

As we arrive on the water of the Mississippi, I hear an incessant ringing tone. It comes from the control structures, massive metal floodgates built nearby to constrain the river to its path. It’s a warning: Stay away. On the maps Ruskey carries, a note declares the structure’s inflow channels “very dangerous… Under no circumstances should any vessel attempt to enter.”

“If you paddled into that, you’d have to make some quick decisions,” Ruskey says.

He estimates that more lives have been lost on the Mississippi and its tributaries than on every other North American river combined. We stay on the river’s far side; I see the structure only when we stop and climb the bluff.

Despite the dangers, in Ruskey’s care I feel safe. He is gentle on the river, and amid close quarters and novice expeditioners he never shows any sign of frustration. Our first full day begins with a prayerful speech; Ruskey compares our crew to a flock of birds. The more that watch the river, he says, the safer it will be.

After the speech, Ruskey performs the same ritual that launches all his trips, a smudge ceremony he learned from a Cherokee healer. While River beats a hand drum, Ruskey waves a smoking bundle of sage over the canoe and its passengers, who turn to face each direction. The ceremony is meant to help us transition from our lives on land to our lives on water.

“We did that in honor of the Mother Mississippi,” he says when the ceremony is through. “It makes me a little bit sad to be leaving the big river.”

Most of this expedition will not be on the Mississippi; it will follow the Atchafalaya River to the Gulf. Thirty percent of the Mississippi’s water is diverted down this distributary, a rate that is set by law. In 1950, as engineers worried that the Atchafalaya might seize the entirety of the bigger river, Congress declared that “the distribution of flow and sediment in the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers is now in desirable proportions and should be so maintained.” (Thus the control structures and their warnings.)

Such seizures are the nature of rivers, when left alone. A river carries soil, which it deposits as it slows, building up new land. Gradually its path to its mouth grows longer. The Atchafalaya now offers a shorter and faster route to the Gulf — making it the route the water would have chosen if left to its own devices. Until the engineers arrived, the river granted itself such shortcuts roughly once every thousand years.

Ruskey is including the Atchafalaya in Rivergator because he believes that for paddlers, too, it is preferable route. South of the fork, the Mississippi is clogged with industry; the Atchafalaya is all cypress woods and back-channels. Wild miles.

Ruskey coined that phrase to describe the places on the river where there is still little evidence of the permanent intervention of mankind. The batture, or the untended land between the levees that still gets flooded each year, is a critical habitat for many species. Two-thirds of the nation’s migrating birds use the Mississippi as a flyway.

Ruskey compares these riverbanks to “long landscapes,” which the Pulitzer Prize-winning biologist E.O. Wilson considers key to conserving biodiversity in a world where species are gravely threatened by the actions of mankind. Long landscapes cut continent-long wilderness corridors through our developed land, allowing animals to migrate — or flee disasters. People used to say that when the South was wooded, a squirrel could travel from Arkansas to Virginia without ever touching the ground. Such long-distance travel may still be possible up and down the Mississippi, Ruskey told me, though only in a stretch five miles wide.

On the river between St. Louis and Baton Rouge, roughly 600 wild miles remain, though the number is always falling. On our first day, Ruskey pointed out a mansion perched above the Mississippi. Less than three years old, the house now disqualifies this stretch as wild.

House or no, it is not a particularly beautiful stretch of river. Sometimes that is the fault of humans, who in places have shoveled refrigerators and other large-scale waste down the riverbank — out of sight, out of mind. (Ruskey notes the coordinates of such dumping sites, as well as illegally gated back-channels, and sends them to a volunteer who works with the Waterkeeper Alliance.) But it’s also one of the last days of winter, and the landscape is grim. The muddy water swells up the levee; in places, only the barren top branches are visible, grasping up from beneath the water.

Three weeks later, back in Clarksdale, Ruskey and I sit in his basement office. I ask about his definition of wilderness. His answer is not at all about beauty.

“When you walk through a city park, it’s pretty,” he says. “You hear birds. But when you walk across a sandbar in the Mississippi, you’re dwarfed by the scale of things. For me it’s a humbling experience, a painful experience. Sometimes it’s a frightening experience.”

Ruskey says the secret to our species’ success has been our ability to manipulate our environment and make it hospitable.

“But we’ve forgotten that it’s important not to be in control.” He wrote about this in his account of the raft wreck: When we let ourselves go, he says, we open ourselves to all the possibilities of the universe.

Up on the streets of Clarksdale, the Juke Joint Festival, one of the region’s best-known celebrations of the blues, its native music, is in full swing. Ruskey has set up a dugout canoe demonstration so that tourists can whack at the wood with an adze. Outside his shop, advocates from a partner nonprofit ask passersby to pledge themselves as “river citizens.” Out back, behind the office, tourists camp along the Sunflower River, paying $25 each to the canoe company for their spots.

Ruskey calls this office the Cave. In 1991, he moved in, just a broke kid looking to learn the blues. It was a storage space for the bar upstairs; he found a pingpong table to serve as a bed.

He was tutored for two years by the late Johnnie Billington, and later, backing James “Super Chikan” Johnson, he toured the country and played a few international gigs. He found a job as the curator at the Delta Blues Museum — a dream job, but a desk job all the same. The river became his solace.

He tells me now that the river always reminds him how he is a tiny fraction of a bigger world.

“That’s very good for the ego, to get deflated,” he says. “It’s the purest form of reality check.”

In 1996, a German tourist heard that Ruskey knew the river, and hired him as a guide. Two years later, the Quapaw Canoe Company was incorporated. (The name means “downstream people,” and honors a tribe that, rather than paddle the river up to the Great Plains, followed the water south.) Over the years Ruskey has led groups for Outside Magazine, ESPNOutdoors and National Geographic, and last year appeared on “Parts Unknown,” Anthony Bourdain’s new travel show. Despite locals’ wariness of the river, in 2013 Quapaw was named Coahoma County’s business of the year. Over his years as a businessman, Ruskey settled into a more typically adult life: He married, fathered a daughter, and moved out of the Cave and into a former boarding house in town.

Now the Cave is cluttered with river driftwood, maps and stacks of magazines. Floor-to-ceiling shelves bulge with books about bluesmen and explorers. Ruskey is in his last year of payments for the building, which he bought in the early 2000s. After serving as landlord for a series of short-lived bars, Ruskey expanded the canoe company to fill all 18,000 square feet. A former distribution center for automotive parts, it now houses living quarters and hostel space, boat storage, and workshops in which Ruskey and his students carve canoes.

Last February the state demanded more than $42,000 in back taxes from the company. Ruskey had been operating under the assumption that, per federal law, activities he conducted on navigable rivers are tax-free.

“I’m not sure we’ll survive this fight,” he told a journalist at the time. But supporters voiced their concerns; the company delivered over a thousand pages of documentation and testimonials about their work. As a result, the state updated its tax code and abated the assessment.

As his business grew, Ruskey has invested in Clarksdale. He launched Friends of the Sunflower River, which is devoted to caring for what Ruskey calls the “blues river,” since it winds past so many musical landmarks in Clarksdale and beyond. In 2011, he incorporated the Lower Mississippi River Foundation, a nonprofit that oversees his community work. Much of that work, including Rivergator, is funded by the Walton Family Foundation.

Ruskey’s biggest project — more important even than Rivergator, in his eyes — is the Mighty Quapaw Apprentice Program. Johnnie Billington, his blues mentor, decomposed the music into its constituent skills and taught them one by one to local children. Ruskey applies the same logic to his various river arts.

“If you don’t share what you have with the youth around you, then it’s going to die when you die,” he says. “I’ve done so much work pushing this boulder up the mountain, and I don’t want it to go tumbling back down.”

He did not plan to apprentice students, he says, but local youth began to hang around as he carved canoes. Someone brave would sidle up and ask what Ruskey was doing. He would answer, and then the boy would fall back into the group. Then someone else would step forward to ask if he could try. Ruskey tells me he sees something of himself in these young men.

“They’re the circles that don’t fit through the squares,” he says.

Some have worked with Ruskey for over a decade, and now, he says, they are among the best paddlers on the river. Most are young black men. The river offers both economic and spiritual solutions in a place where options can be slim: Clarksdale, which like the surrounding Delta is majority African-American, is the seat of one of the poorest counties in America.

“We’re barely scratching the surface,” Ruskey says. “I just don’t have the time to do it. I’d like to do a better job.”

A few apprentices have decided to make careers as river guides. As Ruskey talks, his pride in these young men is apparent. But others, he tells me, come and go. They haven’t found what Ruskey and Brax and River all know: that the wilderness can yank out your heart and then return you to your place in the natural order.

At the boat ramp in Louisiana where I disembark from the trip, two women in a car gawk as we come ashore.

“Don’t you know you’re crazy?” one says. They, too, have lost family to the water. Earlier, as we paddled the canal that would link us to the Atchafalaya, two boys fishing from a motorboat asked our destination. When they heard we were headed for the coast, one declared us insane. We were wearing life jackets; they were not.

But towboats present the paddler’s greatest danger. The Mississippi is a towboat highway: The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers maintains a shipping channel at least 300 feet wide and nine feet deep, the main corridor of an inland waterway that transports more than $100 billion in goods each year. To pass between the Atchafalaya and the Mississippi, boats must use a lock, a kind of river elevator that seals at both ends so that water can be pumped in or out, raising or lowering a boat. The Mississippi, pushed up by its levees, now sits as much as 33 feet higher than the Atchafalaya at the lock.

The lockmaster is required to pass all vessels through, no matter their size. But as we approach, a truck comes screaming down the levee, honking its horn.

“We’ve got a visitor,” River says. As a louder warning bellows from the lock, the driver spills from his truck, furiously waving his arms. I worry the metal gates will open and a towboat will plow forward into our water.

It turns out the lockmaster is simply surprised. He has never seen a boat like ours. After a few minutes of conversation, during which Ruskey hands over another of his maps, we paddle into the canyon of concrete and steel. For 15 minutes we sit while the pumps squeal and squeak and the water falls.

Biologist Paul Hartfield, a friend of Ruskey’s, calls the Mississippi one of the most controlled rivers on the planet. Its floodplain, which once spread as much as 50 miles in each direction, has been reduced to just 10 percent of its historical size. One could argue that nothing on this river is wild, since its boundaries are dictated by the placement of manmade levees. Ruskey’s “wild miles” are simply the places where human influence is least apparent.

When I interviewed Ruskey in the Cave, I pressed him on this fact. He pointed out that at this point human beings have altered every corner of the earth.

“Even in Antarctica carbon dioxide from vehicles is being captured by ice,” he said. And in an engineered world, he added, there is something special about water: It takes away your feeling of control.

Hartfield told me his measure for wildness is whether an ecosystem remains intact. By this metric, despite the engineering, the river is quite wild. No species of fish has gone extinct on the Lower Mississippi, and over the past decade, as the Corps has emphasized the use of “notched dikes,” more water has flowed into back-channels, expanding critical habitats. Pallid sturgeon populations are booming; the fat pocketbook mussel, once found only in an Arkansas tributary, has now migrated into the Mississippi. The population of the interior least tern, an endangered bird species, has, thanks to the development of new sandbars, climbed from 2,000 to 20,000.

Ruskey would love to see this wilderness expand. He told me that if we pulled back the levees and widened the floodplain, it would benefit the entire continent: Lakes would regenerate; landmass would accumulate in Louisiana; the Gulf’s dead zone would shrink. It would help city folk, too: Flood control in New Orleans would be simplified.

John Ruskey holds to a riverman’s rule: Always stop at the first good-looking campsite.

The first night, as we paddle up to Shreve’s Bar, a warm breeze blows off the island, relieving in the afternoon chill. The water is cold — 42 degrees, we estimate — but every day Ruskey is on the river, he takes a swim. At that night’s driftwood campfire, Brax and River tell a story of a frozen expedition. It was December; the air temperature never rose above 32 degrees. But, in grant applications, they had promised to make this trip; they were locked in.

We are just across the river from Angola, the Louisiana penitentiary that is the country’s largest maximum-security prison. A soft glow from its lights is just visible above the trees. But camped on a sandy island beach, my tent backed by a forest of willows, looking up at a sky of bright stars, I cannot imagine a more wonderfully inaccessible place.

As a boy in Colorado, Ruskey and his family packed into a van and drove into the vast Rocky Mountain wilds. Those childhood trips instilled a democratic wilderness ethic in Ruskey: The wildest lands should be available to everyone, he thinks, and not held by private, high-priced hunting clubs, as is often the case in the South. In our interview, he told me that the Mississippi floodplain is just as wild a place as more iconic wilderness parks in the American West, though it’s rarely recognized as such. Too few people have been here.

The second night we park the canoe in a tiny runnel, which by morning has become a full backwater creek. Such seasonal streams are key to river biology, providing a water source for mammals and a place for frogs to lay eggs, which in turn are consumed by fish preparing for spawn.

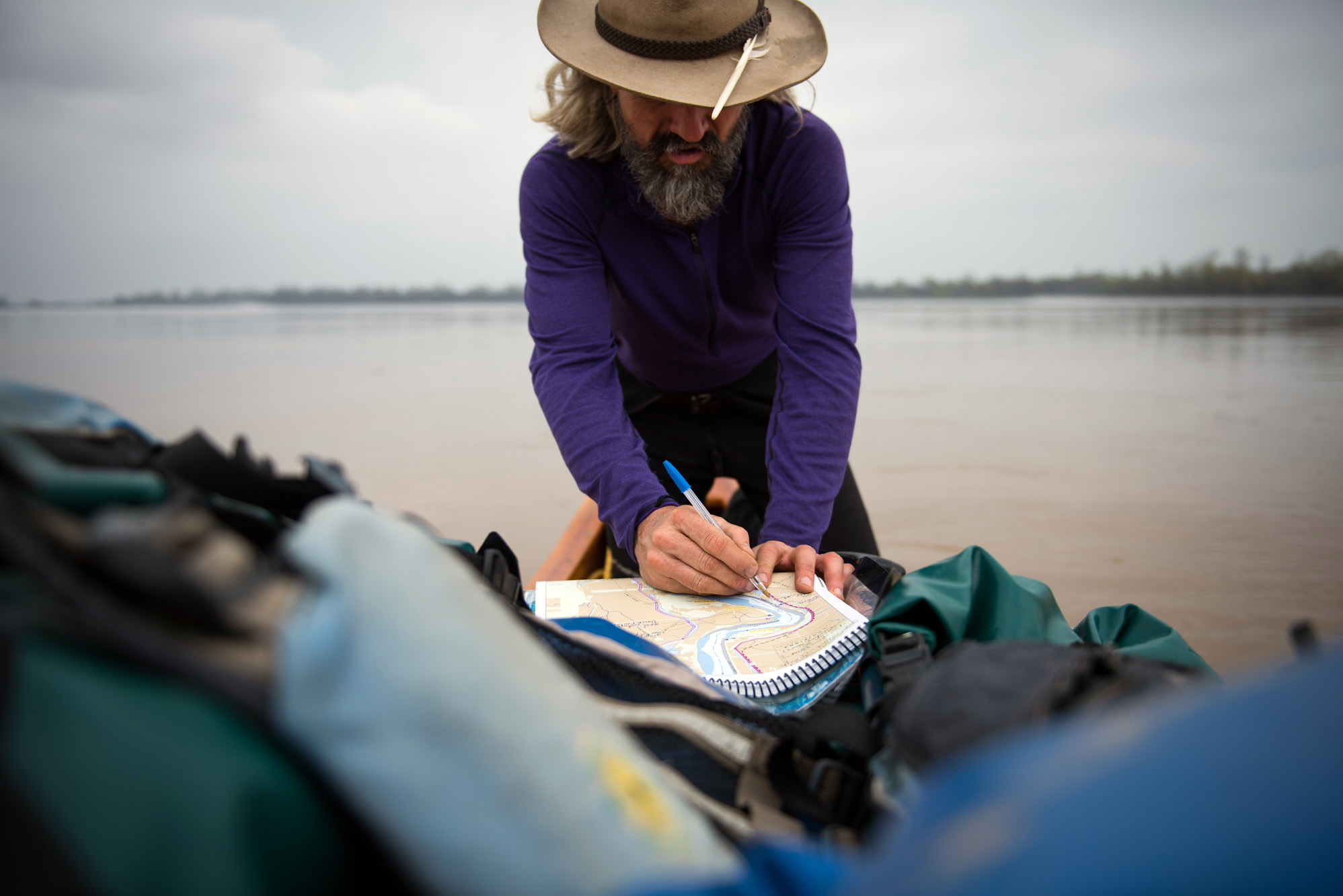

Ruskey sits above the creek, annotating a map. He flags potential campsites and notes a mismarked boat ramp, which, if it ever existed, is now gone. His laptop sits nearby, plugged into a portable battery, so that updates from the expedition can be posted online. Ruskey loves and hates the Internet. Now everywhere is an office, even a riverside bluff.

Each morning the world is wrapped in fog. On Shreve’s Bar, we can hear the towboats churning downriver — invisible, though only a hundred yards away. A pelican loops in the sky, and we are not sure if he can see us through the clouds. While we wait for the fog to lift, the crew journals and draws and drinks river-water coffee. Ruskey disappears.

Ruskey often speaks of “finding the wilderness within,” meaning the biodiversity that is still protected by the river that snakes through our developed South. But I think he is also speaking of the wilderness inside ourselves.

Hartfield told me that he has been on trips where, as soon as camp is set, Ruskey is gone. It can unnerve tourists, Hartfield thinks, to suddenly find themselves alone on the banks. Ruskey, despite a career as a tour guide, is an obvious introvert. He needs time to himself, alone in the wilderness within. Perhaps we all do.

When he is back, Ruskey sits facing the water and plays slide blues on an acoustic guitar. It is less a performance than a meditation.

As he sits on a driftwood log — and later, as he stands in the stern of the canoe, peering into the woods we pass — I feel a bit embarrassed. I’ve spent years trying to fit myself into the clean delineations of modern American success: paychecks and publications and grad school. But here is someone who has learned precisely what he wants and needs from life. He makes me want to devote myself to something just as deeply as he does — to words, maybe, or telling stories; to a river, to conservation, to a job, to a marriage, to goddamn anything. He makes me want to stop wasting time. No more mucking around with the strictures and niceties and control structures of society.

Rivergator is named for “The Navigator,” a bestseller first published in 1801 and reprinted 12 times, a book that guided pioneers through the Mississippi Valley. There’s irony to the name, I think: Those pioneers launched a process that’s proved irreversible, and now we have the sprawling towns and highways of today’s unwild South.

When we talk in the Cave, I ask Ruskey if he struggles with the idea that he is inviting more people into a place he cherishes for its emptiness. Mount Everest, to which he has compared the river, has now become dangerously congested.

“Any place can get overused,” he says. “I don’t know how I’d feel if I arrived on an island and there were 10 camps and 500 people. But if we don’t have more people engaging with [the Mississippi River] for its natural qualities, it will eventually become more and more industrialized. We’ll completely lose what wilderness we have.”

When I ask how he measures his impact, his answer is simple: people. The number of apprentices who have gone through the Mighty Quapaw program. The number who stick with it. The number of river guides he has helped open partner companies or Quapaw outposts in other towns.

“There are hundreds of people up and down the river,” he says.

As we talk, a man knocks on the window and waves goodbye. It’s a friend, Ruskey says, who first came out on the river five or six years ago. He read about Ruskey’s trips and became obsessed. His wife told him to get it out of his system and go. That backfired: Now he organizes a yearly trip.

Ruskey invites me to camp out behind the Cave that night. There are bright streetlights and roaring pickups all night, and I wake to the sound of the last festival revelers departing the nearby bar. But at dawn I’m gratified, unzipping my tent to the sight of the little Sunflower River trickling past.

That afternoon, I join a group of tourists on a day trip — three canoes and many novice paddlers. A group of women sings rounds they composed as children at summer camp. A ponytailed man holds a bongo, and while everyone else paddles, he keeps an unsteady beat. Ruskey, through it all, stays gentle. He explains the passing landscape, and when two towboats appear, he calmly guides the flotilla to safer waters.

We stop on a sandbar for lunch. Once the food is served, Ruskey is gone.

I step away from the crowd — I need a quiet moment, too — and see him. He is taking his river swim. Here, 50 miles from the beautiful island where he nearly died, Ruskey is still at home. I watch his back for the half-second it is visible, and then he is gone beneath the muddy water.