In the 1940s, E.O. Wilson was an Alabama teenager who wandered the bottomland around Mobile and studied its creatures. He never stopped and became the world’s foremost authority on biodiversity. He’s 90 now, but still working, because he knows there’s a way to undo the damage we’ve done to Mother Earth.

Story by Caleb Johnson | Photographs by Irina Zhorov

High on E.O. Wilson’s to-do list, right alongside convincing every nation on Earth to set aside half its land and water for nature, is to get rid of his aluminum cane. For now, he drags the nuisance down a hallway of the private community where he lives in Lexington, Massachusetts. Wilson is tall — more than six feet on orthopedic shoes — and, at age 90, remains quick on his feet, if a little "wobbly," as he describes his lurching gait. It is Valentine’s Day, and many of the elderly women we pass wear outfits in shades of red or pink. They smile at Wilson, who replies with a gentle hello and a slight bow. The retired Harvard professor maintains a school-boyish presence, in part because of a rakish hairstyle and his sartorial choices. During our three days together, with snow and ice blanketing the ground, he wears nothing heavier than an olive-green plaid blazer over a blue button-up shirt.

I’d come to Wilson in search of hope. A new decade had announced itself with the warmest January on record, smoke from wildfires in Australia visible from outer space, and a novel virus had just begun spreading outward from China. Here in the United States, the current presidential administration continued weakening environmental rules and laws by stripping protections for streams, wetlands, and groundwater. I needed to quiet my inner cynic and its grim take on a future shaped by more extreme weather events and leadership refusing to act on scientists' warnings that climate change affects every aspect of our environment, and our health, and will continue doing so if we cannot make major societal changes.

I figured who better to offer hope than Wilson? A world-renowned scientific thinker whose vision for stopping this unprecedented environmental hemorrhaging is based on more than seven decades of careful witness, writing, and work in ecology and conservation.

He leads me to a sunroom filled with tropical plants. We sit on wicker furniture and begin talking about the thing that binds us, the thing I’m certain got me an invitation to spend a long weekend with the man some consider the most important evolutionary biologist not named Charles Darwin: that thing being our childhoods in Alabama.

E.O. Wilson sits in a sunroom where he lives outside Boston. The retired Harvard professor retains a school-boyish presence. On his lapel, he wears a tiny blue pin given to him by King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden, the equivalent of a Nobel Prize for ecologists.

Wilson, who speaks with a whistly lisp, is thrilled to talk about his home with someone who understands its nuances and contradictions. The longer we’re together, the more y’alls he gleefully throws into his speech. At one point he says to me, “I think it’s up to us Alabamians to show people what it means to be well mannered.” I take this to mean he sees an opportunity for our people to lead. I wonder how someone who grew up during a time of strict racial segregation and violence could see this opportunity as anything but long squandered. Today, a majority of Alabamians continue electing officials who protect grandiose monuments to tyranny and hate, who refuse to provide adequate healthcare or education to all the state’s citizens, who allow corporations to pollute our soil and waterways without consequence. Of course, I don’t say any of this to Wilson because the myth of the well-mannered Southerner was hammered into me, too. I find it more natural just to smile and nod.

I learn this will not do.

In conversation, Wilson asks lots of questions. No surprise since he spent 40 years lecturing in classrooms. Initially, I mistake these questions for him pondering aloud. When I fail to respond to one about how he can better support literature in Alabama, he says, “I’m asking because I want to know what you think.”

So I tell him. And as I talk, Wilson takes out a piece of paper and a pen and scribbles notes. Later, he'll reference what he calls "our ideas" and share his plan to turn them into reality. Many things make E.O. Wilson extraordinary, not the least of which is, during his 90th year on this planet, he believes work remains to be done.

I'm gonna write me some music about / Daybreak in Alabama / And I'm gonna put the purtiest songs in it / Rising out of the ground like a swamp mist / And falling out of heaven like soft dew / I'm gonna put some tall tall trees in it / And the scent of pine needles / And the smell of red clay after rain — Langston Hughes, 1940

A whole canon of stories exists to explain the origin of Edward Osborne Wilson’s obsession with the natural world. As with any canon, these stories crystallized and over time were polished by journalists and by readers and, yes, by the subject himself. And, like any canon, the reason these stories became Wilsonian dogma deserves a certain amount of skepticism, which I armed myself with before our meeting. The problem with these stories is, well, they’re difficult to resist, despite knowing a life cannot be understood in a few finite moments, especially when you’re sitting across from the source himself.

Like the summer day in 1936 when 7-year-old Wilson, fishing off a dock near Paradise Beach, Florida, hooks a pinfish then yanks that sucker out of the water with such enthusiasm it whips into his face and one of the 10 sharp spines in its dorsal fin pierces the pupil of his right eye. Despite tremendous pain, Wilson keeps fishing and speaks not a word when he gets home. For months, the eye seems fine. Then one day it turns smoky blue, prompting a trip to a doctor in Pensacola who removes the eye’s lens in a surgery Wilson later describes in his memoir Naturalist as “a terrifying nineteenth-century ordeal.”

Now blind in the right eye, Wilson is left with full vision in the left, which, it turns out, is strongest at close range, meaning he has no trouble seeing, for example, a mass of citronella ants in a rotting stump. It is 1940, and his father’s government job has brought Wilson to live in Washington, D.C. He happily wanders the Smithsonian Institution's National Zoo, the National Museum of Natural History, and Rock Creek Park with his new best friend Ellis MacLeod. Citronella ants are bright yellow and let off a powerful lemony scent. In Naturalist, Wilson writes of finding a nest in the park, “That day the little army quickly thinned and vanished into the dark interior of the stump heartwood. But it left a vivid and lasting impression on me. What netherworld had I briefly glimpsed? What strange events were happening deep in the soil?” He will spend a lifetime asking himself this question. As a result, his posture will change, curving so his gaze permanently directs itself toward the ground.

Later, his family returns to Alabama, settling in a small town near the Florida border called Brewton. First thing, Wilson starts exploring.

“I always went looking for a private space,” he tells me, “And it was the most biodiverse, difficult to get to, unvisited place I could find.” In Brewton, this place is a goldfish hatchery fed by artesian springs and their surrounding bottomland. Wilson dons rubber boots and catches water snakes, including poisonous cottonmouths, that gorge themselves on goldfish. Any creature he can snag, he brings home to study before releasing it again. In Naturalist, he writes, “The hours I spent there were among the happiest of my life… In the swamp I was a wanderer in a miniature wilderness. I never encountered another person there, never heard a distant voice, or automobile, or airplane. The only tracks in the mud I saw were those of wild animals… Although I held no title, the terrain and its treasures belonged entirely to me in every sense that mattered.”

Wilson keeps a small library’s worth of books on science and nature in his office on campus at Harvard University. “I am not a Harvard professor born and raised in Alabama,” Wilson says. “I’m an Alabamian who came up North to have work.”

Perhaps his living situation has something to do with this way of thinking. Wilson’s parents divorced when he was 7 and his father’s itinerant government job meant he attended more than a dozen schools over 11 years. He admits he wasn’t good with girls and he was too puny for serious football. I ask if he ever felt apart from other kids his age and he says no. “Private space was what I most liked,” he says. “I had my creatures, I had my butterflies, my snakes, my nooks and crannies, and I was learning.”

Learning: This is what he’s doing the day he follows a column of dark-brown army ants across his backyard, now in Decatur, Alabama, and the day he purchases dozens of old-fashioned glass prescription bottles and rubbing alcohol from a local drugstore to store ant specimens in, the days he builds glass observation nests for live insects, the days he writes Marion R. Smith, an ant expert at the National Museum of Natural History, who grew up in neighboring Mississippi and encourages Wilson to build an ant collection. And learning is what he’s doing when he asks me questions and jots down my responses on whatever loose paper he can find. He tells me he found ants most fascinating among insects because they live in colonies.

“They weren't some lonesome butterfly in search of a flower,” he says, waving his hands. “They were a mass of insects — and they knew what they were doing.”

Go to the ant, thou sluggard; consider her ways, and be wise. — Proverbs 6:6

Wilson and I talk until lunchtime, then we move down the hall to a cafeteria where he orders a cup of clam chowder and half a margherita pizza.

“I hope you don’t expect me to leave before finishing this,” he says, picking up a greasy slice. After he does just that, Wilson calls a car on his iPhone and we ride into Cambridge. Our destination: the largest collection of ant specimens in the world.

I’d expected gray clouds and dim light, so it feels like a decidedly non-New England winter day. Bright sun, blue sky, though bitingly cold with temperatures in the teens. On the way into town, we pass a stone building where Wilson lived upon arriving as a 22-year-old Harvard doctoral student.

“I expected something very strange,” he says of moving up North, “and I was rewarded by finding an environment that was very strange.” I ask what he means, but before he answers, we arrive at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. Wilson shoves open the car door, swings his large frame out of the seat, and I’m playing catch up with the nonagenarian as he climbs the building’s granite steps.

We take an elevator to the fourth floor. Down a hall and to the left we stop outside a door. Someone has typed “Ant Room” on computer paper and taped it there on the glass. Inside smells like a grandmother’s chest-of-drawers. Ceiling low, windows small. Photos of myrmecologists (ant experts) hang between large metal cabinets. Every cabinet holds a varying number of drawers, and within those drawers are trays, and within those trays are pinned ants. A pin might secure one or two or three or even more ants.

These tiny insects, which evolved from wasps more than 140 million years ago, are Wilson’s long-lasting love. Over the course of his career, he has identified and studied every known ant species in Alabama, as well as others all over the world. With little more than a glance, Wilson can determine if a specimen is a new species or one of the close to 12,000 ants now known. In 1990, he and co-author Bert Hölldobler published The Ants, an encyclopedic study that won Wilson his second General Nonfiction Pulitzer Prize.

For more than a hundred years, whenever someone discovered a new species of ant, they sent it here. Likely there are a million specimens stored within these walls. Some have been described, others have not. One could discover a new species preserved in the trays without setting foot outdoors. This isn’t uncommon. In museums and laboratories around the world, there are bottlenecks of new specimens that sometimes wait decades before an understaffed researcher gets to study them. Luckily, ant specimens remain relatively stable over time once dried, pinned, and placed in glass. Certain species might lose a little color. Otherwise they appear just the way they did the day someone brought them in from the field.

Wilson descends the steps of Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. Founded in 1859, the museum houses one of the largest collections of ant specimens in the world. Many were documented and described by Wilson himself, going as far back as those he found in Alabama during the 1940s and ’50s.

David Lubertazzi, a researcher, and others at Harvard are slowly describing and cataloging the entire ant collection in a digital database that will be available to researchers everywhere. Lubertazzi shows us around the room. He holds each tray with care; one slip of the hand could destroy unknown amounts of knowledge. He guesses they’ve cataloged and digitized about 150,000 specimens so far. We are not here to see just any ant though. Wilson is determined to find ones from, where else, Alabama.

Lubertazzi starts searching. The cabinets are organized by genera, the taxonomic rank above species. He opens one, removes a tray, tilts it toward us and smiles. “Ed’ll have a tale to tell about this ant,” he says. The specimens are so small at first they’re hard to see. A minuscule tag reads Temnothorax tuscaloosae, an ant Wilson described in 1950 while a graduate student at the University of Alabama.

“That’s one that goes back in time," Wilson says. He recalls visiting a greenhouse one day with a botanist colleague. Wilson simply dug up a plant and in the dirt discovered T. tuscaloosae, previously an unknown species of ant. Now all these years and miles later, from the red dirt of West Alabama to a lab in Cambridge, the specimens remain.

“It’s a great, warm feeling,” to be able to revisit his life’s work this way, he says, “to know that work we do is going to stay here forever.” Wilson doesn’t mean just the specimens themselves, but all that can be learned from understanding them and their role in a given ecosystem.

Wilson found and described these ant specimens in Alabama more than 70 years ago. They're collected along with millions of species inside Harvard's Museum of Comparative Zoology.

Wilson is now known for his big ideas on evolution and conservation, but his career began in taxonomy. This most basic form of science involves naming and classifying organisms according to a specific set of rules that dates back to ancient Greece. The Swedish scientist Carl Linneaus, whom some call the original naturalist, invented our modern system of taxonomy in the 18th century. Each day we spent together, Wilson wore a tiny blue pin on his lapel given to him by King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden for his contributions to biodiversity research, representing the equivalent of a Nobel Prize for ecologists. The same emblem was given to Linnaeus back in the 1700s for his work Systema Naturae, which identified every known species with a set of Latin names based on their similarities and differences.

To understand an ecosystem, people must know what all it contains, and how all those individual species function within it.

When Linnaeus published his study in 1758, he recognized about 20,000 species in existence around the world. By 2009, according to the Australian Biological Resources Study, that number had reached almost 2 million. Wilson and other scientists believe the total number of species on Earth, both known and undiscovered, could reach 8-9 million. Linnaeus intended to describe them all. Wilson long ago took up that mantle. A lofty goal, but spend time around Wilson and you get used to seemingly impossible ideas. He frames what we don’t know about our planet and what lives on it as a thrilling mystery, an opportunity to learn rather than a problem too daunting or, worse, too late to confront.

He says most people don’t realize how little we know of life on Earth or how much biological diversity still awaits discovery. Progress has left the public believing that what he calls the “unfinished mission of science” is complete, that the discovery of a new species is a notable event when, statistically speaking at least, it is not.

This is especially true for the region that shaped him.

“The South is a major stronghold of biological diversity,” he says. He gives an example — 24 types of oaks and 126 types of fish exist within the Mobile-Tensaw River Delta, which collects river flow from the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains further north. “When these [ecosystems] are destroyed, or even reduced significantly, there’s going to be a loss to the country forever.”

This loss is happening at a significant rate in the South, which holds seven of the 10 states with the highest number of endangered species. Alabama alone has 131 endangered and threatened species, behind only Hawaii and California. Across the world, according to an Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) report, as many as 1 million plant and animal species are now at risk of extinction because, in large part, of how we farm, fish, mine, log, and poach. Now you might ask, why should I care whether Alabama’s Red Hills salamander exists? Or whether we examine one of the millions of unknown insects? As Wilson writes in Half-Earth, “Human beings are not exempt from the iron law of species interdependency. We were not inserted ready-made invasives into an Edenic world… The biosphere does not belong to us; we belong to it.”

Now, because of a complicated web of man-made reasons, the biosphere faces what Wilson calls a three-headed environmental crisis — climate change, mass extinction, ecosystem collapse.

“This paper-thin layer of species and ecosystems that make up the environment we live in is threatened,” Wilson says. When I tell him that, anecdotally, it seems like many of our fellow Southerners don’t understand the urgency, he disagrees.

“I’m heartened by the ease by which people listen to you when you talk about species extinction,” he says. “That they understand. Climate change was a little bit more difficult to explain and convince people with.” I’m impressed by his generosity toward a place that often flouts his life’s work — that of preserving biodiversity while there’s time left. This optimism is what I admire most about the man, what brought me to him in the dead of winter, his refusal to believe that continuing his life’s work, even now, is just a shout among the ruins.

Let me enter a tract of rich forest and I seldom walk more than a few hundred feet. I halt before the promising rotten log I encounter. Kneeling, I roll it over, and always there is instant gratification from the little world hidden beneath. – E.O. Wilson, The Future of Life

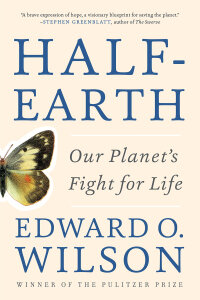

In 2016, Wilson published Half Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life, in which he claims that if every nation sets aside half its landmass and waters for nature, then we can ensure the continuing existence of 85% of all species on the planet — including ourselves. The book garnered acclaim and criticism, but, like much of Wilson’s work, its central tenets have become more mainstream over time.

The first line of the book is, in Wilsonian style, a simple question: “What is man?” Wilson lists some generous and not-so-generous suggestions before writing, “Humanity’s grasp on the planet is not strong. It is growing weaker… Because the problems created by humanity are global and progressive, because the prospect of a point of no return is fast approaching, the problems can’t be solved piecemeal.” In other words, we need what Wilson describes to me as “a moonshot of global conservation.”

A full half the planet's landmass is necessary, Wilson writes, because large plots can sustainably support more ecosystems and more diversity. According to the IPBES report, more than a third of the world’s land surface and nearly 75% of its freshwater resources are currently devoted to crop or livestock production. Three-quarters of the land-based environment and about two-thirds of the marine environment have been significantly altered by human actions. We live in the Anthropocene, the Age of Man, a geological epoch in which the entire Earth has been altered by humanity. Wilson’s Half-Earth goal offers a way back to a biosphere in which humans coexist with, rather than rule, millions of other species.

It’s hard for me to believe world leaders will take such drastic action when they couldn’t even hold together the Paris Agreement, which, according to current research, wasn’t enough to prevent catastrophic climate consequences anyway. Wilson admits Half-Earth is ambitious. He makes clear he is not asking for the planet to be divided up differently or for the ownership of land to change hands. Instead, he asks for “… a major shift in moral reasoning, with greater commitment given to the rest of life…” In the book, he writes, “People understand and prefer goals. They need a victory, not just news that progress is being made.”

One victory Wilson mentions several times is the Paint Rock Forest Research Center. In Northeast Alabama, on about 4,500 acres where the Tennessee and Paint Rock rivers slice into the Cumberland Plateau, the center serves as a training ground for what its executive director, Bill Finch, calls “Wilson’s Army”: a new generation of researchers who understand both ecosystems and microbiology, the big and small parts of our natural world.

Finch is proud of his state’s biodiversity the way some Alabamians are proud of their chosen college football team. Without being prompted, he rattles off how many species of oaks can be found in the Red Hills near Monroeville, how many freshwater fish can be found in the Mobile-Tensaw River Delta, tells me that Alabama has the greatest number of hickory species, of magnolia species in North America.

“I could go on,” he says.

Over the course of an hour-long phone call, he does.

Wilson has published dozens of books, which have been translated into many languages, including Anthill, a novel about his boyhood in Brewton, Alabama. Various copies fill several shelves in his office, where he still comes to work each week.

Through a United States Department of Agriculture grant, the center works with Alabama A&M, a historically black college in Huntsville, to introduce underrepresented students to ecology and train them in the field. Finch hopes to develop a program that introduces high-school juniors and seniors onto a track toward undergraduate science programs.

“We want to create a training center for this new generation to understand diversity in all of its aspects,” he says. “And we also realized we didn’t think we could understand diversity if we weren’t looking at it with diverse eyes.”

This comment reminds me of a poignant moment in Wilson’s Naturalist. It is 1944 and Wilson, an Eagle Scout, has been invited to speak about scouting to a group of young black men near Brewton, Alabama. For the first time in his life, he is forced to confront his white privilege. Wilson writes, “When we left I did not feel pride in the example I was supposed to have set; I felt shame. I was depressed for days. I knew in my heart that those boys, mostly two or three years younger than I, would have few real advantages no matter how gifted or how hard they tried. The doors open to me were shut to them.” Wilson tells me that the older he gets the more he regrets he wasn’t able to know his black peers in Mobile and other places he lived throughout his childhood.

Besides working with in-state universities, including Wilson’s alma mater, the University of Alabama, Finch also works with out-of-staters such as Stephen Hubbell, a prominent ecologist based at UCLA. The idea is to attract an array of brilliant minds to rural Alabama and train them in conservation work that can then be applied globally. This work involves identifying every plant and animal species on the land to understand the role each plays in the ecosystem. Finch and others are working to establish a 50-year research plot inside which they will identify and catalog any woody stem over 1 centimeter tall. Researchers will collect data that will tell them, in part, how the forest survived and adapted to previous changes in climate — and help them make good conservation decisions for the future. Right now, about 15 acres of the 150-acre plot have been tagged, and about 200,000 stems are being monitored.

I ask Finch how he speaks to local people about climate change. He brings up a group of hunters who are members of a club established on the land before the research center existed and who still hunt there.

“I can say, ‘You know, we haven’t seen rain like this.’ And they say, ‘You know, you’re right.’ And I say, ‘You know, it’s funny because we’re getting these warm spells interrupted by cold spells. It didn’t used to be this way.’ And they say, ‘You know, you’re right.’” Finch laughs. “They see these effects. They want to know about them. They want to understand them.”

So much of our common way forward relies on how we communicate our ideas for the planet we share. As usual, Wilson understood this before many others. He speaks and writes plainly yet exquisitely. When I ask how we convince our fellow Southerners that climate change will continue to have an outsized impact on the region due, in part, to its geography and economy, Wilson says, “It’s a contradiction of the kind that begets literature, begets serious deep reasoning about the history of a place and what is best for its own self-image.” He pauses. “Let’s use a different language to talk about what Alabama has.”

He relies on biblical terms to explain, saying, “If we can hold to what we’ve been given, so to speak, by the rest of life in our own emergence as a species, then humanity can live forever. And Earth can be a paradise. There’s no reason we can’t think of ourselves as immortal as a species. And the planet, this biosphere, as immortal with us.”

Those words — paradise, immortality — make my ears prick up. Like myself, Wilson was raised Southern Baptist. Neither of us regularly attend church anymore. But such a formative part of one’s past isn’t easily left behind. In our conversations, Wilson compares himself to a preacher with a message to spread. At times he dismisses Christianity altogether, calling it a tribal endeavor. At one point he compares it to another of our shared cultural touchstones.

“When the Crimson Tide pours onto the field, you can see [tribalism] illustrated in raw, naked form,” he says.

I mention how he and I have been identifying ourselves by tribes since I arrived.

“Yes, we have,” he says with a knowing grin.

Now he calls his faith profoundly humanistic. “It’s faith in humanity,” he says. “An absolute faith because we don’t have anything else to fall back on.” He believes if he sits down with, say, a Southern evangelical, they can agree on certain things. He will not change their minds on the origin of humanity; nor they change his. But they can find ways to channel their fervor toward a shared future. “If you want to be deeply religious in the Baptist manner, which I was raised, well, fine, believe,” he says. “Because in believing you’re reinforced toward the kind of behavior that would make the most out of your and my existence on the planet.”

Before we leave the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Wilson shows me one of his private spaces. To get there, we pass through a room filled with bound dissertations written by former students, a quiver of large arrows given to him by Papuan natives, and more figurines, photographs, and drawings of ants than can be counted at a glance. Wilson stops, opens a file cabinet and runs his fingers across the tops of many curled papers. His ongoing personal collection of every published text on ants he can find. A physical manifestation of his brain.

He jams a key into a door, next to which hangs a poster for the Monroeville (Alabama) Literary Festival, and we enter a rectangular office. A cream-colored phone and a lamp sit atop his desk. Otherwise, the only piece of technology I notice there is a magnifying glass. On one wall is a world map so old it still shows the Soviet Union. On another, a sign that reads “Alabama: We’re Kind of a Big Deal.”

“I am not a Harvard professor born and raised in Alabama,” Wilson says. “I’m an Alabamian who came up North to have work.”

I ask if he enjoys saying that line in front of his Harvard colleagues, maybe ruffling their feathers just a little bit.

“You can put it somewhere that the subject of your article is indeed a bitter Southerner,” he says, laughing at himself.

On the way out, Wilson wants to show me one last thing. We turn right from his office and on the other side of a door enter a public exhibition space. The enormous bones of a right whale hang from the ceiling, stuffed gorillas and zebras and rhinos stand frozen in glass cases below us. Wilson tells me this collection was started by Louis Agassiz, a Swiss biologist who wanted to educate the public about creation by allowing them to witness it up close. At this moment in history, it was more common to listen to lectures than visit museums filled with specimens. It’s fitting, I think, for Wilson’s office to be on the other side of a thin wall since he’s spent much of his life bringing big ideas to the general public through his books.

As we leave, Lubertazzi, the researcher, shares a bit of trivia. Despite founding the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Agassiz was one of the last major scientists to disagree with the theory of evolution. In fact, he was a staunch critic of Darwin.

Wilson jumps in, reminding us, “But Darwin didn’t build a museum.” Another example of Wilson’s generosity even toward those with whom he doesn’t see eye-to-eye.

I decline to accept the end of man. It is easy enough to say that man is immortal simply because he will endure: that when the last dingdong of doom has clanged and faded from the last worthless rock hanging tideless in the last red and dying evening, that even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking. – William Faulkner, Nobel Prize speech, 1950

Our last morning together, Wilson and I meet again in the sunroom downstairs from the apartment he keeps. I come prepared with questions I hope will goad him into speaking philosophically or poetically about complicated problems which have no simple answers. He doesn’t take the bait, which makes for a thrilling back-and-forth. Wilson is not prone to romanticism, like me. Rather than disappoint, realizing this actually makes ideas like Half-Earth seem more hopeful, because I know Wilson has thought them through carefully and rooted them in decades of scientific knowledge.

This time, I ask bluntly how he remains optimistic in the face of environmental catastrophe.

“Self-understanding,” he says. He retains a sense of responsibility to affect change while he still can. And like a good Southerner he comes back to faith. He credits Belle Raub, a close family friend he lived with for a time as a boy in Pensacola, with introducing the notion of belief. Though he left behind the religious tenets she taught him, he didn’t forget their power.

“I always felt a responsibility to do something right that was religious in intensity,” he says to me. “I think it’s possible to have a secular, scientific view of the Earth, particularly its living part, nature. If we protect that then we’ll be protecting our own future, and together we can find potentially eternal existence.”

Again, that biblical language. I tell him experiencing nature always stirs something spiritual in me. In turn, Wilson recites a line from a book he’s working on. “Nature is the metaphoric goddess of all things in the universe, outside of human control.”

Soon the conversation steers toward mortality. Wilson lowers his voice. I ask if he thinks about death.

“I guess we all do,” he says. “I’ve lost all my friends. All of them now are gone. So I’m the last survivor.” He continues mulling this out loud. “I don’t know how we should face this except to worry about how we live. If you want to press me on it, I don’t worry about it. I know it’s coming, but I don’t worry about it. I expect to be gone… No one in my family except for one first cousin ever made it past 91.”

Wilson, who speaks with a whistly lisp, talks about Alabama with the author, a fellow native of the state. Over three days, Wilson gleefully throws more y’alls into his speech while discussing everything from religion to tips on catching poisonous snakes.

This summer Wilson will reach that prophetic age. Before the COVID-19 outbreak, he’d made plans to visit the Amazon and collaborate with local researchers on ways to stop the slashing and burning of the rainforest. He’s also writing yet another book on, what else, ants. Perhaps all the projects, all the work, help put off the number on the horizon. But I sincerely believe Wilson when he tells me he doesn’t worry about death. He sees its inevitability no differently than he sees his work — necessary. He learned this early on while delivering newspapers around Mobile before dawn, then going to school all day, spending afternoons building serious collections of specimens from the woods and wetlands. There’s nothing special about this ethic either, as far as Wilson believes. It’s life how he’s lived it — and will continue to until the end.

Wilson has argued that if we don’t soon change the way we live we will leave behind the Anthropocene and enter the Eremocene, or the Age of Loneliness, a term Wilson has popularized that defines an epoch marked by an existential and material isolation resulting from having extinguished so many other forms of life. To his point, a new study published in Nature suggests that mass extinction will look like a cliff rather than a slope as previously predicted. Ecosystem collapse in tropical oceans could begin as soon as next decade, followed by collapse in tropical forests — the most diverse ecosystems on the planet — in the 2040s. In other words, as Wilson writes, the biosphere will be reduced to “our domesticated plants and animals, and our croplands all around the world as far as the eye can see.”

Scientists conceive of time differently than us layfolk. Millenia rather than days, centuries as opposed to minutes. E.O. Wilson is no exception. He assures me it isn’t too late to avoid an Age of Loneliness. He is also known for popularizing the term biophilia, or the innate pleasure we take in the presence of other organisms.

“We can confer immortality on the rest of life if we wish to do so,” he tells me. I leave feeling somewhat convinced, and I wonder what would happen if more people were imbued with a similar sense of possibility and responsibility toward our present environment. What if we considered the changes we can make right now, especially those of us living in the South? Wilson senses such a moment on the horizon.

“We have a region that is waiting to be heard,” he says.

Who am I to doubt?

EPILOGUE

Late last week, I spoke on the phone with E.O. Wilson. The community where he lives is, of course, locked down to visitors and following CDC guidelines strictly. He compared living there right now to being trapped in a bubble. However, Wilson remains healthy and, as usual, in high spirits.

“I’m using this time — and trust me, there’s plenty of it — to read and research for a book I’m writing on ecosystems,” he said. I told him I was glad to hear that and admired his determination to forge onward with his work during this uncertain time. We talked a little about some writing projects of mine, and he encouraged me to keep pursuing them. As the conversation wound down, Wilson told me how much he hoped we could spend time together again soon. I agreed. His suggestion for what we do when able: convene in Alabama and go searching for a particular species of salamander that lives there.

Caleb Johnson is the author of the novel Treeborne and a previous contributor to The Bitter Southerner. His work can be found in Gravy, The Paris Review Daily, and Southern Living, among other publications. Caleb grew up in Arley, Alabama, and now teaches writing at Appalachian State University.

Irina Zhorov is a writer, photographer and producer, focusing on the natural world and how we live in it. She’s working on a novel set in Soviet Siberia.