Sixty years ago, small-town Alabama musicians, many of them sons and daughters of farmers and sharecroppers, came together in homegrown recording studios in Muscle Shoals, and proceeded to lodge their little town forever in the minds of music lovers. Today, a small Shoals record label, Single Lock, is changing minds about exactly what “Southern music” means — and collapsing the barriers between the hometown legends of old and the music of the young.

Story by Amy C. Collins | Photographs by Abraham Rowe

Those who know about the Shoals, the quad-city community made up of Muscle Shoals, Florence, Sheffield and Tuscumbia, Alabama, honor its deep, rich history in the American music industry. They know something special happened there, something that changed the sound of American music forever. They might know it was magical, even miraculous, how this thing happened. They might know the Shoals is a “cool” place nestled into the northwest corner of a state not considered “cool” in the political or forward-thinking cultural spectrum of today’s society. They might know that the largest of the four towns, Florence, has a thriving downtown atmosphere that includes restaurants with James Beard Award cachet and bars that rival the highbrow standards of big-city folk up North and out West. They might even know the music scene in the Shoals is, even today, alive and kicking, that native son Jason Isbell, a Grammy-winning songwriter/musician, produced the inaugural Shoals Music Fest in 2019 that brought Mavis Staples and Sheryl Crow to town.

All this in an area surrounded by farmland and populated by God-fearing folk, who for seven years were my neighbors.

Those who know about the Shoals the way I do might even know there’s an indie label, Single Lock Records, that’s putting out killer art, regionally focused, and that with each release is effectively redefining Southern music — with the old tropes of cowboy boots, tall hats, and the white patriarch’s ego no longer at the center. Even the catchall Americana category that once blanketed all outsider artists has increasingly lost relevance in an ever-widening circle of artistic creation.

“I’m sitting here in my office and looking at the wall, and the wall is basically every record we’ve ever released,” says Single Lock partner Reed Watson during a phone interview a few days before a planned Australia tour with Cedric Burnside, cancelled shortly thereafter when stay-at-home orders and closed borders took effect. Watson is most often the face of the label, the words man, the one with his boots daily on the ground. He’s also a talented drummer who plays with multiple artists on the label, both live and in the studio.

“I often do this in interviews because it’s a good way for me to think back on where we’ve been and where we’re going.” Watson is patiently taking me through the label’s evolution from the beginning up to its newly refined vision. “All of this stuff is all Southern music, but none of it really definitely lives in a certain genre. It can all live in two, three … five different worlds, and none of it is really what you’d expect.”

Four of Single Lock’s five owners (left to right): Will Trapp, Ben Tanner, Reed Watson, and John Paul White. A fifth partner, Reed Trickett, stays out of the publicity shots for the most part, but has served the label as a critical advisor in recent years.

Music nerds who happen also to be highly skilled and accomplished musicians run Single Lock. Three of the five owners regularly play on the albums the label produces, tour with those bands, or are solo artists on the roster. They know great music, they know phenomenal songwriting, and they are on a clear mission to collect great new music across the region. Since the label’s inception in 2013, Single Lock has compiled a growing list of artists whose work bends the rails upon which folk, country, blues, rock and roll, electronic, and pop travel.

Still, what they’ve accomplished — that they even exist — is tied forever to those magical, even miraculous things that happened 60 years ago at two small recording studios.

“We stand on their shoulders a lot, and that’s a proud thing,” Watson admits. But Single Lock does more than merely stand on the shoulders of American music giants; they invite them into the studio to record with the younger musicians. It’s a situation not too unlike what happened on a particular day in Muscle Shoals 53 years ago.

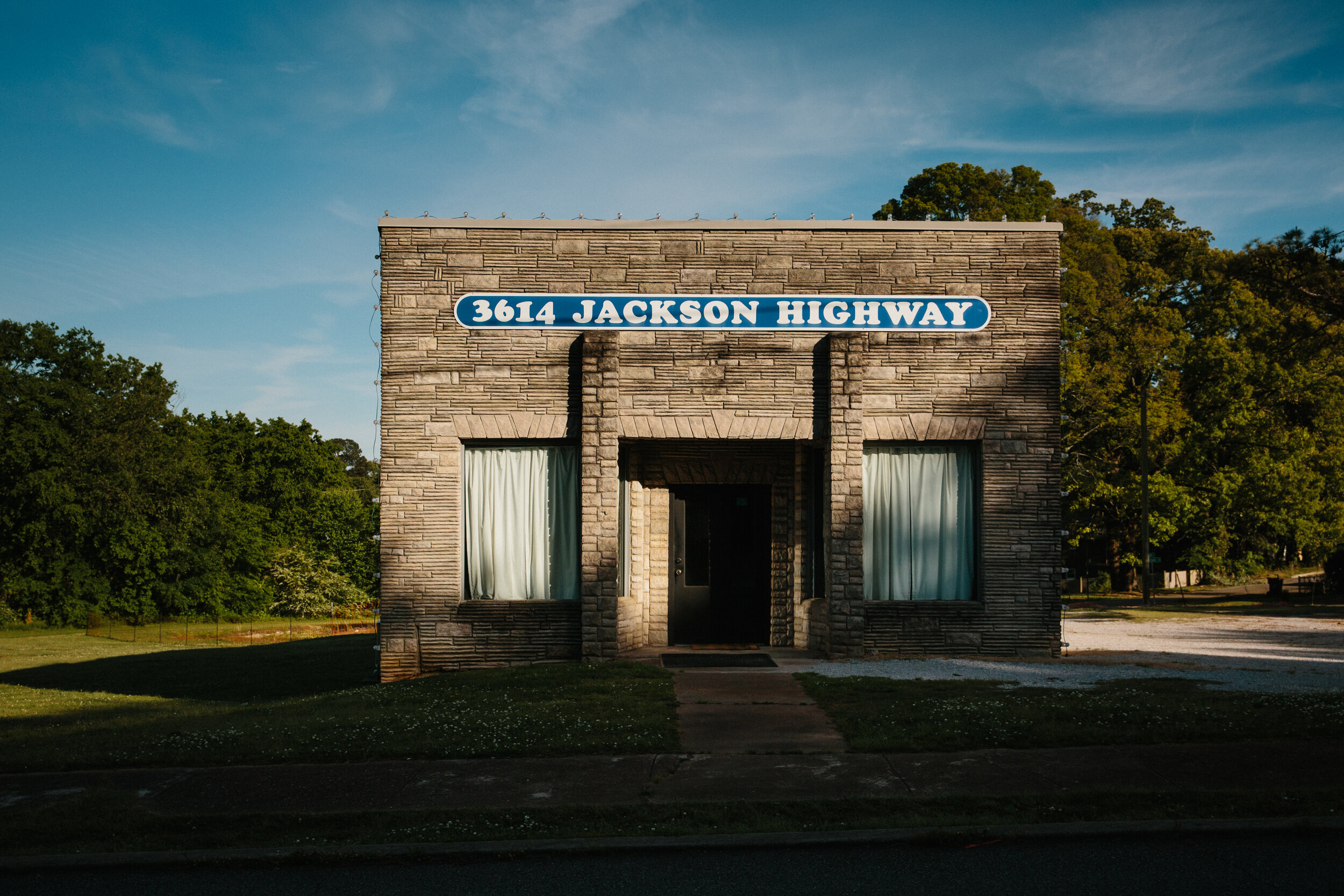

Muscle Shoals Sound at 3614 Jackson Highway in Sheffield.

On January 24, 1967, a young singer with nine albums under her belt but not one hit walked into FAME recording studios in Muscle Shoals, where a group of session players, most of them white men she had never met, were ready to work without expectation. Her previous records had been made within a clearly defined structure; play the song as it’s written and call it a day. But that wasn’t working for anyone in the room. There was tension in the air. No one knew how to start, and the song she’d played for them wasn’t grabbing anyone.

After several minutes, the room still quiet and the vocalist reserved, keyboardist Spooner Oldham started riffing a simple tune on the Wurlitzer electric piano. Roger Hawkins added a soft drum beat. And then, seated at the grand piano, she sang the words, “You’re a no good heartbreaker, you’re a liar and you’re a cheat.” It’s a story that’s been retold many times and immortalized in the documentary film, “Muscle Shoals.” That was the day Aretha Franklin found her voice — and became the Queen of Soul. It was also the day Muscle Shoals, Alabama, would anchor itself so firmly in the annals of American music history that nearly every ear came to know this iconic song.

FAME in Muscle Shoals and Muscle Shoals Sound in Sheffield sit across the Tennessee River from Single Lock headquarters in Florence.

In 1961, a mad genius with a massive chip on his shoulder and a drive to prove himself to the world opened a recording studio in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, a place no one would point to on the map unless they were trying to find their way home.

“The pictures of that place when it was built … there’s nothing around it!” Watson says of Hall’s FAME studios on Avalon Avenue. It grew up out of the Alabama chert, in the middle of a cotton field in a dry county.

“Who in their right mind would put their time, money, heart and effort into opening a recording studio in Muscle Shoals, Alabama?” Watson asks.

The studio made its first hit when it released Arthur Alexander’s “You Better Move On,” then Jimmy Hughes’ “Steal Away,” and within a matter of a few years, it had helped take Aretha Franklin from a no-name great voice to the powerhouse “Queen of Soul.” Rick Hall was the conductor on that train.

FAME has recorded hits here at 603 Avalon Avenue in Muscle Shoals for the last 58 of its more than 60 years in existence.

Hall was a musician and songwriter himself and a native to the area who joined up with fellow musicians Billy Sherrill and Tom Stafford in the late 1950s to open FAME, an acronym for Florence Alabama Music Enterprises, in downtown Florence. After a falling out, Stafford kept the publishing catalog and Hall took the name across the Tennessee River and declared he would do it his way. His way, however inflexible and demanding, turned out damned successful. When a studio produces hits like “Respect,” “I Never Loved A Man,” “Dr. Feelgood,” and “Save Me” — all on one album - other artists will want to record there, and so others followed suit, many under the guidance of Jerry Wexler’s Atlantic Records, which was, at the time, the premier R&B and soul record label in the country. FAME is still a fully operational recording studio today.

But what made FAME so attractive was the sound created there, and the phrase “Muscle Shoals sound” quickly became part of music-biz conversations. That sound came from a group of humble session players who laid down a funky rhythm that was distinctly its own, just a bunch of white country boys who taught themselves and each other to play the black music they loved. Eventually dubbed “the Swampers,” these guys, with their bass, drums, guitar and keyboards, backed black artists such as Wilson Pickett, Percy Sledge, Arthur Alexander, Aretha Franklin, Etta James, Clarence Carter, and the list goes on.

How does that even happen in the rural South of the early 1960s?

“The only word for it is miraculous,” says Watson. “We don’t exist without them.”

Just a few of the artists who made hit records in the Shoals that became standards of American culture: Aretha Franklin, Arthur Alexander (second from left at top), Wilson Pickett (second from left at bottom), Percy Sledge, Etta James (far right at top), and Clarence Carter (far right at bottom).

The Swampers — Jimmy Johnson, Roger Hawkins, Barry Beckett, and David Hood — left FAME to start their own studio in 1969: Muscle Shoals Sound Studio at 3614 Jackson Highway in Sheffield. “Take A Letter Maria” by R.B. Greaves was their first hit, which went all the way to No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100, and it set the tone for years of success with a discography that includes tracks by the Rolling Stones, Cher, Paul Simon, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Bob Seger, Willie Nelson, Cat Stevens, Rod Stewart, George Michael, and so many others. It is still a fully operational recording studio.

Bassist, Swamper, and co-founder of Muscle Shoals Sound Studios David Hood (father of Drive-By Truckers frontman Patterson Hood) bought his first bass guitar at age 18 and started playing in a rock and roll group that played covers of songs they’d heard on the radio. Hood’s first studio session was in 1965 for Quin Ivy, who was a disc jockey at WLAY radio, owned a record store called Tune Town, and, after seeing Rick Hall’s success at FAME, had opened his own sound studio, Norala Recording Studio. The track was Percy Sledge’s “Warm and Tender Love,” the follow-up to “When a Man Loves a Woman.”

“I went from barely knowing how to play to at age 23 I’d played on some gold records,” Hood says of his early career success. He learned a lot in a short time, listening intently to records by Booker T. & the M.G.s, Sam and Dave, and other soul productions from Memphis and Detroit to pick up what they were doing. That influence became the backbone of what the Swampers did for FAME and later for their own productions.

At age 76, Hood is still working and has played on several records produced by Single Lock.

“I’m the old guy now,” he says with a laugh. He recently spent two days working in the studio with a group of young people, the oldest behind himself, he figures, was under 40. “They do know the history a little bit and all the records I’ve worked on and things. I have to earn their respect again. I’m not just the old guy who’s done a lot of stuff a long time ago, I’m still doing stuff.”

The Single Lock shingle as it hung over the company’s original headquarters in Florence.

What Single Lock is doing today isn’t a complete departure from what Hood and his partners were doing in the 1970s. They share a committed desire to make world-class records. Hood says with reverence for Single Lock, “Trying to do what me and my partners did 40 years ago, and they’re trying to do it now, and, boy, it’s so hard now. Everything has changed.” Record sales today are almost a by-product for musicians; a few decades ago, they were the only thing that made a career.

“Now everybody gets the music for free, so that means these younger musicians have to travel all the time playing shows to make their living,” Hood adds. “In the old days, we would record something with an artist and take it to the local radio station and it would air and we’d sit in our cars and listen to it and judge the mix and all that kind of stuff.”

Most artists today also hold day jobs or night jobs or some type of flexible contract work to supplement their income or to provide the lion’s share of what our present economy demands just to keep the lights on. The late Donnie Fritts, songwriter, pianist, and Single Lock artist, used to lament the same loss. He was the same age as Hood, but once he got his foot in the music door, he was able to dedicate a lifetime to a pursuit that very few artists can even hope to achieve now. Just as that era of American industry passes, many of the early pillars in Muscle Shoals’ history have gone. Guitarist, sound engineer, Swamper, co-founder of Muscle Shoals Sound Jimmy Johnson died in 2019, Donnie Fritts less than a month before him, Rick Hall in early 2018.

“The legendary music scene that they made the movie [“Muscle Shoals”] about, that pretty much dried up in the early ’80s. There was kind of an exodus,” says Patterson Hood. The songwriter and Drive-By Truckers co-founder is a product of those lean years. He left the area in 1994 for Athens, Georgia, with longtime friend and bandmate, Mike Cooley. Soon after their Athens arrival, the two started DBT, a band widely noted for honest songwriting that skirts the traditional norms of Southern politeness in favor of painting a truer picture of the region’s good and bad traits. Their most recent album, “The Unraveling,” was released in early 2020.

“There was nowhere to play, no infrastructure for a live music scene and the scene that had inspired all that success in the old days wasn’t ever placed on playing live, it was strictly a studio scene,” he says. “When I was growing up, most locals didn’t know about the music that had happened there. There were all these hit records that had come out of Muscle Shoals, and most people living there had no idea. It was almost like a secret thing that was going on, and to some extent, I think it was.”

In Watson’s estimation, “Patterson has taken the role of being an alternative voice for Southerners, which I think is powerful. Throughout his entire career, he has pointed back to this community. There’s no telling how many people found out about Muscle Shoals through the Drive-By Truckers. For that, he should be commended a hundred times over.”

Jason Isbell, a songwriter, Grammy winner, solo artist and early member of Drive-By Truckers from 2001 to 2007, grew up down the road from Florence in Green Hill, Alabama. He too came up during the lean years, though a few years junior to Patterson and Cooley. He too pays frequent homage to the area’s rich history.

“If you take those two out of this area in the ’80s and ’90s, what is there?” Watson says. “It’s a pretty bleak spot if you remove them from the timeline. They are both indispensable.”

Keyboardist, sound engineer, and founding Single Lock partner Ben Tanner, at work in the Muscle Shoals Sound control room on an upcoming record, the first hip hop ever cut at the legendary studio.

When the documentary, “Muscle Shoals,” came out in 2013, the blind spots of locals began to fill. All of a sudden, every Shoals citizen knew all about their cultural ancestry, and they bear-hugged it with genuine pride.

“The documentary was such a big deal because no one had done a good job ever of framing that narrative, what it really meant, what went on,” says keyboardist, sound engineer and founding Single Lock partner, Ben Tanner. “The people who did it were more concerned about making records than telling their story.”

The movie tells a romanticized version of the story, barely touching on the risks faced by African Americans and whites who made music together during the heat of the Civil Rights movement, and attributes the bulk of success to a single person, Rick Hall. But it brought renewed interest in the area from music lovers and makers and gave permission to young locals to take up an instrument where they might have previously felt that football was the only option. It also helped birth a little indie co-op record label called Single Lock, which wanted to test the waters on an increasingly uncertain music-industry sea.

Rick Hall and the Swampers had long ago laid the bricks for the path of Muscle Shoals music, and the movie ignited a forward-looking spirit in the community, but one man served as the deep link between the Shoals music of yore and the new music Single Lock dreamed of producing. It was the presence of songwriter and keyboardist Donnie Fritts on the Single Lock registry that brought the label serious respect from the elders and helped hone the label’s evolved vision.

“Donnie gave us some legitimacy with that generation,” says Tanner. Fritts’ connections went far beyond Muscle Shoals. His presence on the Single Lock label garnered respect from Nashville hit songwriters like Dan Penn and John Prine, guys from Fritts’ generation whom he considered close friends as well as collaborators.

In 2015, Single Lock released Fritts’ first solo album in almost two decades. “Oh My Goodness” featured musicians from the old camp as well as those from younger generations. That period coincided with my years in the Shoals, when Donnie became my friend and mentor. We often ate lunch together. He was over 70 when the album came out, and he told me more than once that he was astounded that anyone would take a chance on such an old guy, especially an unfamous one. We would talk about writing and music and staying the course toward a dream. He wanted to read whatever I was working on, and he always made me feel like my efforts meant something. But that was Donnie. He made everyone feel like their creative endeavors, their mere existence, meant something, especially the people who were on the fringes of the scene. There was always a humility about him, and he never expected anyone to return the trust. Then Single Lock did.

John Paul White and the late Donnie Fritts

Founding partner Will Trapp recalls the question of what to do with Donnie once the album was ready for release. T-Bone Burnett had sent Donnie to Single Lock partner John Paul White to make the record, but the label was still in its infancy. Fritts was insistent he be a part of their story.

“He said, ‘I want to be with you guys, I want this record to come out on your label,’” Trapp says. “He didn’t really know us at that stage, and I think we all got pulled into his personal connection to us, and we wanted to give that connection a chance to happen for other people.”

Fritts’ gift was that his reach was broad and it touched audiences in ways most artists can’t accomplish.

“To listen to Donnie play, he would draw you in, in a way that a star might not because they might be more into themselves,” Trapp says. “Donnie was into the song or the scene or the room or somebody in the room and he’d just pull them in. He did that to all of us.” It’s the reason dry eyes could be scarce at a Fritts show, especially in a small venue.

Donnie Fritts: 1942-2019

In August of 2018, Single Lock released what would be Donnie’s final album, “June (A Tribute to Arthur Alexander).” That spring, he performed on The Bitter Southerner stage at the Word of South Festival in Tallahassee, Florida. John Paul White, David Hood, and Reed Watson accompanied him on stage.

“That was one of the only times we had an opportunity for Donnie to share his tribute to Arthur Alexander. It was a big thing for him,” Watson says. “I could tell that we were nearing the end of Donnie’s ability to get out and play a lot. That part was tough. It wasn’t a perfect set, but it was a poignant set. It meant the world to him, and that meant the world to us.”

What Fritts might not have fathomed for himself was that he became a bridge between the past and the present within the structure of Single Lock. “When he passed, the soul of this label in a lot of ways had passed,” says Watson, who was very close with Fritts and often performed with him.

Donnie Fritts was decidedly unmarketable by industry standards. He was an incredible songwriter with a voice like a wayward angel who’d been wandering the desert for a century. His work is impossible to peg and his style outside anything trendy or exactly familiar, his lyrics volleying between joy and suffering and always with a pure heart that forms a visceral connection with the listener. He is irreplaceable and completely unmatched.

A thumb through the Single Lock catalog reveals more evidence of unboxable talents, gems that exist even if a formula to contain them has not yet been written.

“A lot of the folks we work with are inspirational,” says Trapp. “They inspire other musicians in ways that other folks don’t. For people who really understand the craft of songwriting, they find the differences in our artists, the inspiration.” Fritts, a unicorn in his own right, was the archetype of the Single Lock way.

A few of the acts on the Single Lock roster: Nicole Atkins, Space Tyger, Lera Lynn, Mia Dyson, The Blind Boys of Alabama, Belle Adair, The Bear, Exotic Dangers, Erin Rae, Dylan Leblanc, & Caleb Elliot. Photos courtesy of Single Lock Records.

“When your own music attorney is like, I trust this label, wholeheartedly, that speaks volumes,” says Birmingham songwriter/musician Duquette Johnston, former bass player and founder of the ’90s rock band Verbena, who also has a handful of solo albums that range in sound from organ and tamborine-laced rock to cinematic soundscapes and heavy vocal harmonies. Soon, Single Lock will re-release Johnston’s 2006 album “Etowah,” which chronicles his time spent in prison, plus a new record later this year. Johnston has been in the business for roughly 30 years and has worked with both corporate and indie labels. For him, Single Lock makes sense because they respect his artistic vision and are willing to wait until all the parts come together.

“I think they understand the importance of history and telling the stories, and they understand the importance of artist development and letting an artist make the best record that they need to make,” Johnston says.

While there are a handful of cross-genre labels owned and operated by artists for artists, they are few and far between. This alone sets Single Lock apart from their contemporaries. When the money men also live the emotional, spiritual and intellectual struggle of the art maker in their own lives, that empathy runs deep.

“It can be a weakness of ours that we wear our artists’ hats too much sometimes,” says John Paul White. “We probably disadvantage the label to the betterment of the artist, but it all pays off. That we are actually facilitating that sound in their head they want to get out, that’s where our bread is buttered, helping them articulate that thing in their head that they couldn’t do by themselves.”

Single Lock recording artist Dylan LeBlanc and John Paul White warming up backstage at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium before Dylan’s show there in 2016.

White’s rise to musical success is different than most. He was a student at the University of North Alabama in the entertainment department when he earned an apprenticeship with esteemed songwriter Walt Aldridge. That led to a position as a staff songwriter for a major Nashville publishing house. Later he was one-half of the duo the Civil Wars, a partnership that put a few Grammy Awards on his mantle, and has since released multiple solo records on his joint venture label.

Cedric Burnside is a newer artist signed with the label, though he started touring and playing drums with his grandfather R.L. Burnside when he was 13, nearly three decades ago. His album “Benton County Relic” was released in 2018, a nod to his Mississippi Hill Country blues lineage.

“I was afraid they were gonna want to change how I record my music, like other record companies,” Burnside says. “But that’s not what they wanted to do at all. They wanted me to be me. It turned out to be one of the best things I ever did in my career.”

“I was afraid they were gonna want to change how I record my music, like other record companies,” says Single Lock artist Cedric Burnside, pictured here at his home in north Mississippi. “But that’s not what they wanted to do at all. They wanted me to be me. It turned out to be one of the best things I ever did in my career.”

It was always going to be an artist-run label with the integrity of the art at the center.

“It started as this very local, slightly regional collective co-op idea,” says Tanner of Single Lock’s origins. “And then the St. Paul [and the Broken Bones’ “Half the City”] record, being the third thing that we put out and the first thing we did top to bottom, was so big and so successful, it kind of put us into hyperdrive, into a whole other part of the business and a kind of stratosphere that if we thought about it at all, we thought would be years down the road, not the third record.” Tanner, himself a talented keyboardist and sound engineer from Muscle Shoals, got his start at FAME after college. It was an admin position, but he was able to shadow the engineers on duty, fill in for demos and small projects and even play on a recording if something simple was needed. He knows first hand the difficulty and rewards of working with Rick Hall.

“When I was growing up here, there was a lot of stuff that was good for Florence, good for around here,” he says. “I think one of the parallels is that Rick really wanted to make world-class records, here. We want to do the same thing. We want to put out world-class stuff and conduct ourselves in a way that’s not just some little local label.”

Tanner, Trapp, Watson, and White on the front steps of Single Lock’s current home.

As expected of artists, they lead with their hearts. “It’s subjective about what’s great music and what isn’t and what will sell and what won’t, and you never know until you put it out there,” White says about the group’s approach to working with artists. “But we know that we love it, and we try to make that the continuing criteria, not, ‘Will this sell?’” White resists my pleas to define what makes an artist interesting to the label, instead describing it more as a feeling than an intellectual pursuit. Beyond that, he allows only that every record on the label is song-driven, that great writing is the key.

White and Tanner are businessmen, too, and money is necessary, but behind closed doors, the conversations sound more like frugal family vacation planning than big enterprise. How much can we spend to enjoy the seaside without trying to bottle the ocean? That approach had them stumble upon their current mission to redefine Southern music. If the art moves you, don’t pin it down. Just help share it with the world.

The label’s Florence office sits adjacent to their recording studio, a nondescript house with each room dedicated to storing particular families of instruments. They record many of their releases there, but also at FAME, Muscle Shoals Sound, and other studios. Liner notes for every production live freely on their website as well as a love list of independent record stores across multiple continents and three iterations of Single Lock T-shirts, which carry their own social currency.

Single Lock, as a noun, a commodity, a philosophy, is a collection of great music from all influences and sensibilities, music made without narrow boundaries, without dollar-focused directives, and with 100% artist integrity at its core. You don’t have to be an A+ music aesthete or discophile to get it.

But you can always trust that Single Lock will deliver exceptional art — stuff that re-examines what Southern music is and rewrites the rules of how it is made, much like the giants did six decades ago did in Muscle Shoals.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this piece described Donnie Fritts as 10 years older than he actually was.

A Single Lock showcase in 2014 at the Norton Auditorium at the University of North Alabama in Florence. Tanner, on keyboards at left, White (at center) and Fritts (at right at his beloved Wurlitzer) with a host of the label’s artists, including Dylan LeBlanc and members of Steelism, Belle Adair, the Bear, and the Pollies.