Beneath the popular folk song, “Swannanoa Tunnel,” and beneath the railroad tracks that run through Western North Carolina, is a story of blood, greed, and obfuscation. As our nation reckons with systematic racial violence, the story of this song points to the unmarked graves of the hundreds of wrongfully convicted Black people who died building the tunnel.

By Kevin Kehrberg & Jeffrey A. Keith

One rail of this investigation is industry. The other is a song.

They pass through the Swannanoa Tunnel and over unmarked graves.

here’s a reckoning taking place in Asheville, North Carolina. The Vance Memorial, a towering obelisk long considered a staple of the city skyline, has been shrouded in black because Zebulon Vance, a former governor and U.S. Senator, was a slaveholder who fought for the Confederacy. The city also removed a bronze marker honoring Robert E. Lee located near the base of the monument. On the street surrounding the shrouded tower, local artists have painted the words “Black Lives Matter.” And on July 14, 2020, the city council unanimously voted to pass a resolution aimed at increasing generational wealth among African Americans through reparations.

In front of the Buncombe County courthouse, a Confederate monument is gone, and county commissioners will vote today, Aug. 4, on a "Resolution to support community reparations for Black people in Buncombe County.”

Another reckoning is taking place in the traditional music world that claims Asheville as a prime hub. Performers of bluegrass, old-time, and folk music celebrate the multicultural roots of these genres, but the traditional music scene has been predominantly white for more than a half century. Now, many musicians are urging one another to engage with the complexity of lyrics and songs rooted in the Black experience. For the past eight years, we have been doing this work by studying a single song - one called “Swannanoa Tunnel” - that commemorates a long railroad tunnel just beyond the city limits east of Asheville.

“Swannanoa” is a corruption of the Cherokee phrase “Suwa’lĭ-Nûñnâ’hĭ” that means “the trail to Ani-Suwa’li,” referring to the Siouan-speaking people who lived just beyond the mountains. A popular local myth is that Swannanoa means “beautiful waters” and alludes to the Swannanoa River, which flows down from the Swannanoa Gap before rolling through the small mountain town of Swannanoa and on into Asheville. Train tracks snake along this key river valley, and they go through a tunnel under the gap.

The Swannanoa Tunnel transformed the Blue Ridge Mountains. This 1,832-foot tunnel is the longest in a complex of six tunnels completed between 1875 and 1879, and the railroad that goes through them connected the mountain’s primeval forests to the Atlantic seaboard. Within a decade of the tunnel’s completion, Asheville grew from a rural town of 2,600 people to a small city of 10,235. Lumber crews scoured the mountains, reducing old-growth trees to sellable timber.

As white scholars of Appalachian history and music, we had assumed this much accounted for why a song about the tunnel existed, but then we learned three critical facts that forever changed how we think about this tunnel and its song. First, the Western North Carolina Railroad (WNCR), the state-owned corporation in charge of building the line, used mostly Black people on its construction crews. Second, those workers labored at gunpoint. Third, this was their song.

Asheville Junction,

Swannanoa Tunnel,

All caved in, babe.

All caved in.

The WNCR’s construction was a murderous business. From 1875-1891, the corporation forced an unknowable number of wrongfully imprisoned African American men and women, mostly from the eastern part of the state, to work under the watchful eyes of armed, white overseers. In 1879, a white traveler passed through the Swannanoa Gap and described what he saw. “No criminals among them,” he said of the hundreds of Black people leased out by prisons to keep costs down. “But the South must have convict, if not slave labor to finish her railways.”

Many so-called convict laborers were forcibly worked to death. Some died of sickness, others in accidents. Guards killed workers, too. A representative legend endures: Two brothers walked away and ignored warnings to turn back, essentially accepting death over continuing to work in chains.

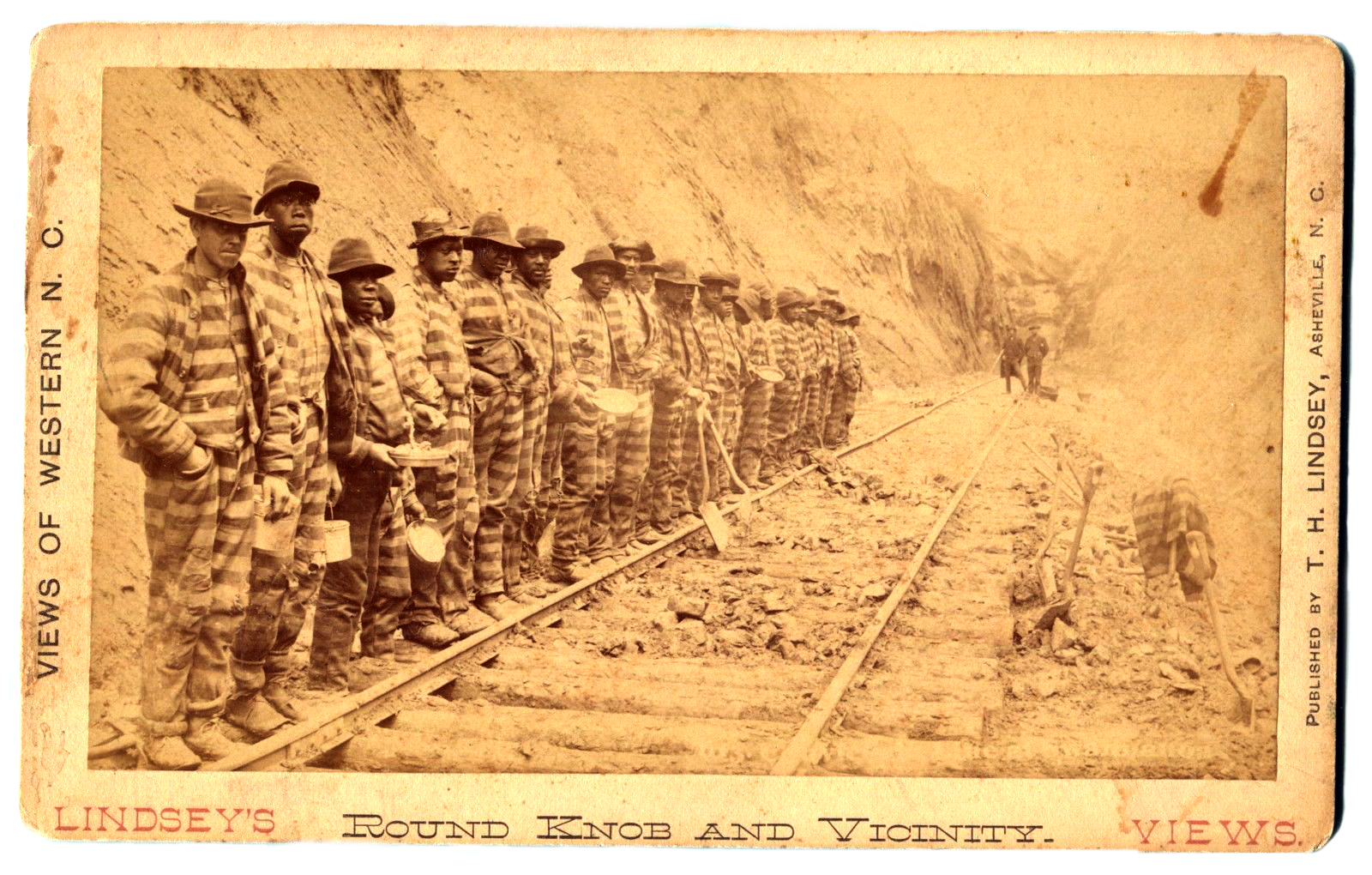

Round knob stockade, circa 1878.

In a well-documented event, 19 shackled men drowned when their transport boat sank into the icy Tuckasegee River. One imprisoned worker named Anderson Drake saved a guard, but the hero remained a convict laborer because the guard accused Drake of stealing his wallet during the rescue. That night, a prison camp guard whipped Drake as the enchained bodies of 19 men remained at the bottom of the freezing river.

These train tracks are more than a transportation route. They’re the closest thing there is to a monument for hundreds of people who lost their lives building the railroad. An inadequate historical marker nearby notes the tunnel’s length and adds, “Constructed by convict labor.” According to multiple newspaper accounts and a government engineering record, laborers who died near the Swannanoa Tunnel were buried along the tracks. There’s no reason to doubt these graves exist, but their locations are unknown. No one has gone looking for them.

Official and media accounts of the time cast a positive portrayal of the Swannanoa Tunnel, celebrating industry, progress, and humanity’s dominance over nature. In song, the tunnel is a site of bone-crushing tragedy.

Last December,

I remember.

Wind blowed cold, babe.

Wind blowed cold.

“Hail to the Chief!” heralded the Asheville Citizen on March 13, 1879. The chief was James W. Wilson, a former Confederate officer and the president of the WNCR. He was hailed for completing the Swannanoa Tunnel by having workers blast through the gap from both the east and west simultaneously. They mixed nitroglycerin into a thick mash with sawdust and cornmeal before tapping it into drilled holes in the rock. The railroad needed to climb 1,100 vertical feet in a distance of less than three and a half miles, a gradient far too steep for a train. This dictated a circuitous, nine-mile route and several tunnels to reach the Swannanoa Gap and, beyond it, the high valleys of Buncombe County.

Wilson telegraphed Governor Zebulon Vance, a close friend and another former Confederate officer. “Daylight entered Buncombe county today through the Swannanoa tunnel; grade and centres met exactly.” Shortly after Vance read those words, 20 incarcerated men and a guard were crushed to death by a cave-in at the Swannanoa Tunnel.

The deadly work continued. At least 120 people died while working on the tunnel. More than 300 died at other points along the line. These are conservative estimates that fall short of an elusive total, but the railroad building effort claimed hundreds of Black lives.

The twisting route necessary to gain a rise of 891.5 ft. between mileposts 113 and 122 is shown in this map of the WNCR, dated 1881.

Wilson and Vance understood convict labor as an economic efficiency. A formal letter between them recounted the amoral cost benefit. “The actual cost of supporting the convicts up here is a little under 80c. per day: feeding 7c., guarding 10c., and the remainder for clothing, medical attention, &c.” In exchange, “the State is amply repaid in the quadrupled value of land and other property.”

With poor housing, muddy work, and an insufficient diet, more death arrived on freezing winds. Penitentiary doctors ignored the pestilence. Rebecca Harding Davis, a white journalist from Pennsylvania who published a travel article about the region in Harper’s Magazine in 1880, noted how “the wind drove from time to time with angry shudders” through the Swannanoa Gap. She recounted that Black laborers “were driven into a row of prison cars, where they were tightly boxed for the night.” Years later in the Asheville Citizen, one of Wilson’s employees acknowledged the existence of a mass grave near the tunnel, “where the unmarked graves of 400 convicts give mute testimony to the death toll reaped by pneumonia.”

If disease threatened incarcerated workers, then white political ambition further imperiled them. Two years before he was hailed as chief, Wilson literally used the muscles of prisoners to secure his own political power. To keep his position as president of the WNCR, Wilson needed to deliver an engine to Buncombe County before the end of 1877. To remain a beloved governor in his hometown of Asheville, Vance needed Wilson to succeed. The tunnel wasn’t done yet, so the two friends had a common interest and a shared problem.

Wilson came up with a solution. Lay temporary tracks up the eastern side of the gap. Tether together hundreds of men, mules, and oxen, and force them to haul a 17-ton train engine up the slope using ropes. Then lay temporary tracks down the western side of the gap, and force the men to assure its safe descent using back straps. James Wilson’s idea, in other words, was that incarcerated workers should pull a locomotive over a mountain.

Wilson followed his hideous plan. Vance, who is characterized as an “avowed racist” by his biographer, reflected on the undertaking casually and callously. “No one but Jim Wilson would have thought of or executed such an idea.”

The governor stood in awe of his friend’s ambition, but he was hungry for glory. Wilson obliged, inviting Vance to blow the first train whistle in Buncombe County. The Asheville Citizen likened the county’s residents to Rip Van Winkle, saying they had slept in ignorance of progress until Vance made his move. “The Governor climbing into the engine — the first pioneer of modern civilization among a people just waking — placed his hand upon the throttle valve and the glad blue hills re-echoed the long expected sound.”

The historical record suggests that this photo is of the Salisbury, the 17-ton engine that was pulled over a mountain by the human strength of incarcerated workers — a feat that bolstered the political careers of James Wilson and Zebulon Vance and imperiled the lives of the Black men who completed the task, men whose names were not recorded.

While Wilson and Vance basked in their unearned accolade, another sound came from the incarcerated people who did the hard labor. They used a song to remind one another of the recent news about John Henry. Scott Reynolds Nelson’s book Steel Drivin’ Man investigates the real life of John Henry, a Black Union veteran who received a grossly inflated sentence for a minor crime in Virginia. The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway worked him to death as a convict laborer in the Appalachian Mountains, where he died during the summer of 1871.

The folk song commemorating Henry’s downfall became famous in the 20th century after E. C. Perrow, Carl Sandburg, and other white folk song collectors took note of its popularity, but it survived during the late 19th century as an urgent yet underground reminder for workers to avoid danger. At the Swannanoa Tunnel, “John Henry” was both a current event told in song and an object lesson, reminding workers that Black freedom amidst white supremacy could be lethal.

Irony, inversion, and obfuscation braid through these stories. John Henry, a Union veteran, died young and imprisoned; Vance and Wilson, Confederate veterans, died old and elite. Newspapers made a habit of referring to Wilson as “Major Wilson,” referencing his former Confederate status; the names of incarcerated workers appeared nowhere in those newspapers. (172 laborers, however, were named in the 1880 census so as to increase the area’s political representation.)

Once the Swannanoa Tunnel welcomed regular traffic, the glory that shone upon people like Wilson and Vance grew bright enough to blind many to the truth. The Carolina Watchman announced that the Swannanoa Tunnel’s completion meant North Carolina, at last, was a “state without an east or west.” The report erased incarcerated workers from the story, claiming the construction had been “at last accomplished by the resolute courage and discriminating judgment of men who were for the most part citizens of this community.” But the song “Swannanoa Tunnel” endured.

When you hear my

Watchdog howling,

Somebody’s ‘round, babe.

Somebody’s ‘round.

Drone footage by Nolan Swoap

“Swannanoa Tunnel” - also sometimes called “Asheville Junction” - began as a hammer song. Hammer songs make up a subcategory of work songs associated with the building of railroads. “John Henry” is by far the most well-known example, and certain verses associated with it sometimes appear in “Swannanoa Tunnel.” Both songs helped time the hammer blows of teams drilling holes in rock for nitroglycerine, where one worker held and twisted a large bit while another (or two) hammered the bit between turns. Timing was of the essence. While the rhythm had to be exact, the lyric structure of the song welcomed flexibility, allowing workers to improvise verses as long as they maintained the poetic cadence. Hammer songs became running commentaries on the trials and tribulations of forced labor under cruel conditions, an expression of lament, and a form of creative resistance.

During the building of the WNCR, laborers sang outside of work hours, too. Saturday nights and Sundays offered the only opportunities for rest and recreation. A guard during this time, interviewed decades later for the Asheville Citizen, recalled that “music and singing were engaged in freely” at the camps on the weekends, and that “some of the prisoners could play the violin or pick the banjo and guitar.” He continued, “Visitors often came in from the community around and listened appreciatively to the prisoners’ performances.” At some point, these listeners began to learn, and “Swannanoa Tunnel” began to travel.

The frets on a banjo neck look like railroad ties, with the strings spanning them like rails that parallel the white and Black dimensions of folk music in general and “Swannanoa Tunnel” in particular. As a musical instrument, the banjo symbolizes the incorporation of African cultures into the very essence of what America claims to be, but the truth of its African lineage remains hidden to or denied by many. Similarly, the song “Swannanoa Tunnel” entered the canon of Western North Carolina folk music in ways that covered up its backstory.

In both cases, the confusion stems from the legacy of those who tried to control and present the music of America’s “folk.” Bascom Lamar Lunsford, a prominent white folklorist in Western North Carolina during the 20th century, adopted the banjo as his “basic instrument,” and he became obsessed with presenting his notion of the region’s folk music to a wide audience. He was most responsible for establishing “Swannanoa Tunnel” as a representative song from the region, but he was not the first to document it.

In 1905, Englishman Cecil Sharp left his post as the principal of a London music conservatory to direct his full attention to documenting English folk songs. Sharp came to believe that they had been preserved in southern Appalachia as cultural orphans, uncorrupted by the Industrial Revolution. He began making collecting trips throughout the region, and in 1916, Sharp collected a version of “Swannanoa Tunnel” sung by two white women who lived a couple miles west of the tunnel.

A year later, Sharp published it as “Swannanoa Town” in his influential collection English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians. The lyrics “Swannanoa Tunnel” had become “Swannanoa Town, O.” In his endnotes, Sharp references “John Henry” as an “American variant” of the song. In other words, Sharp claimed “Swannanoa Town” (explicitly), “Swannanoa Tunnel” (by extension), and “John Henry” (for good measure) as English in origin.

Such distorted conclusions resulted from Sharp’s understanding of folk music that placed Europe in general and England in particular at its center. This warped logic led Sharp to claim English ownership of music that was 200 years and 5,000 miles removed from his homeland. Travel diaries from his Appalachian collecting trips also reveal a categorical disdain and dismissal of Black people. Had he known the true source of “Swannanoa Town,” he may not have even bothered to preserve it. Despite such views, the influence of Sharp’s work lingers on today in common cultural perceptions of American folk music.

Beyond the bizarre mistitle, Sharp’s version is anomalous in other ways. It’s in triple meter, like a waltz. This phrasing removes the song’s utility; the beat on which workers would have swung the hammer is gone. Despite some lyric parallels with other versions, Sharp’s transcription contains no references to railroading, a cave-in, or a tunnel. Through poetic and sonic omission, this version conceals a record of social injustice and tragedy.

English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians inspired a frenzy of folk song collection among American scholars, institutions, and enthusiasts, and Bascom Lamar Lunsford joined the effort. Lunsford was an Appalachian Renaissance man who ran local newspapers, practiced law, and had helped the so-called Dixiecrats regain political control of Western North Carolina in the early 20th century. However, Lunsford’s true calling — as he described it — was “spreading the gospel of folk music.” He boasted about his “memory collection,” a mental repository of more than 300 ballads, songs, and tunes from which he could draw at will.

Growing up, Lunsford learned “Swannanoa Tunnel” from Fletcher Rymer, a local white banjo player, and it became one of his signature songs. In the 1910s, he devised a public lecture-performance called “North Carolina Folklore, Poetry, and Song,” in which he prominently featured “Swannanoa Tunnel” with banjo accompaniment. The song traveled extensively via Lunsford’s efforts, and he assured its present-day ubiquity among folk musicians in the region.

In 1929, Lunsford included the song in a collaborative publication with Lamar Stringfield, a Pulitzer Prize-winning composer and symphony conductor who helped establish the North Carolina Symphony in Raleigh in the 1930s. It was common at the time for American classical composers — both Black and white — to follow the European model of studying folk material for inspiration and elevating it to the level of “high art.” In their collection, 30 and 1 Folk Songs from the Southern Mountains, Lunsford and Stringfield arrange “Swannanoa Tunnel” as “an old labor song” with instructions that even detail the proper place to “grunt” in performance.

They make no mention of African American people or convict labor, citing only the “section hands” who built the tunnel. One of the printed verses, in fact, revises the story in a sickening fashion: “When you hear my pistol firin’, nother n----- dead, baby, nother n----- dead.” The simple piano accompaniment signals the collection’s intended market: middle-class, amateur music makers — presumably female and white — providing entertainment in the home parlor. At the risk of putting too fine a point on this: white mothers likely sang these words to entertain their children.

Lunsford included this verse in his first recording of “Swannanoa Tunnel” in 1935, when he recorded his “memory collection” for the Department of English at Columbia University. He also includes commentary on the recording, calling the song “indigenous to that great mountain country” around Asheville. Lunsford mentions “Negroes” as the “construction men” who built the tunnel and brought the song, but then emphasizes that it “has been influenced a great deal by mountain sentiment,” explaining that, “where music is brought in, the mountaineer works it over and uses it to his own taste.” That is to say, Lunsford was defending the song’s shift in perspective from an incarcerated laborer in an unfamiliar place to a local wage worker or guard, a process that dramatically transformed it from a Black work song to a Southern Apartheid-era white, working-class anthem.

Lunsford recorded “Swannanoa Tunnel” at least two more times in the 1940s: once for the Library of Congress and again for what eventually became an album for Folkways Records, Smoky Mountain Ballads. Both versions omit the “pistol” verse, but Lunsford’s notes on the recordings make no mention of Black people or the forced convict labor that built the “great” and “famous” Swannanoa Tunnel. Instead, he specifically cites Sharp’s claim that “it is a variant of an old English song.” Lunsford’s preference for a white narrative of Appalachian folk music is no secret; over the course of his more than four decades at the helm of Asheville’s historic Mountain Dance and Folk Festival, the only known appearance of a Black artist was in 1942, when dancer Billy Smith performed.

Three men, names unknown, stand with banjos behind the Swannanoa Hotel in Asheville, 1890. Photograph by Marriott Canby Morris, (1863-1948)

Artus Moser was a colleague and contemporary of Lunsford, and another white luminary of Western North Carolina folklore. Born in the area, Moser taught at various colleges and universities throughout Appalachia before settling in Swannanoa in 1943. He collected folk music for the Library of Congress, including numerous versions of “Swannanoa Tunnel.” One of them came from his father, an early-20th-century forest warden in Buncombe County.

In 1955, Moser recorded the song for his own Folkways album North Carolina Ballads. Moser credits Black convict laborers as its source, but he uses Sharp’s lyrics and title — singing “town-o” instead of “tunnel” — and performs it in an arrhythmic and unaccompanied ballad style. In the album notes, Moser promotes the same colonialist understanding of the folk process as had Lunsford 20 years earlier. He disputes the idea that Sharp’s variant title and text reflected a misunderstanding of local dialect, asserting rather that “the people in the area, proud of the song and the things it helped to accomplish, adapted it to their own devices when it no longer served as a work song.”

Audio recording courtesy of UNC Southern Folklife Collection, Artus Moser Papers, FD-20005/537.

Moser also taught “Swannanoa Tunnel” to younger singers. His daughter Joan Moser recorded and submitted it in 1960 as part of a Fulbright application. She credits it as a “Negro work song,” but performs it in a style similar to her father and even begins substituting “town-o” for “tunnel” toward the end of her recording, symbolizing the song’s ongoing metamorphosis. Mickey Miller was another young white folk singer who learned “Swannanoa Tunnel” from Artus Moser and recorded it for her 1959 Folkways album. In the album notes, she wrote, “One of the highways into Asheville from the west goes through the Swannanoa Tunnel. We haven’t found whether or not any disaster ever occurred there… [My] rendition excludes two Jim Crow verses which are perhaps the reasons why this song has not been more popular.” The real story behind “Swannanoa Tunnel” was continuing to fade, and the song’s supposed origins had shifted to align with whiteness and racism.

In the 1960s, “Swannanoa Tunnel” traveled far beyond the boundaries of Western North Carolina, mostly by way of white performers capitalizing on the folk music revival. Paul Clayton and Erik Darling both released versions. The former learned it from Lunsford; the latter from fellow New York City revivalists. It also emerged on the West Coast. Les Baxter, the famed Hollywood composer, made an arrangement for his concert folk group the Balladeers (of which David Crosby was apparently a one-time member). It was also recorded by The Johnson Boys, a California band who heralded themselves as “the 1963 campus folk favorites.”

From 1916, when the song was documented and mislabeled as an English folk song, to the present day, “Swannanoa Tunnel” — also sometimes called “Swannanoa Town” and "Asheville Junction" — has appeared on multiple commercial recordings released by white artists active in folk, old-time, bluegrass, and related genres.

As the song spread, its backstory only grew more obscure. The Johnson Boys sing of the “Swannanoa Mine,” the site of an apparent coal mining disaster. Other versions misremember details or insert unrelated folk tropes. Lyrics mentioning Tom Dooley appear; there are references to gold-mining; one version by a psychedelic rock band sings of the “Nashville Junction” that has all caved-in.

Another compelling example comes from Roscoe Holcomb, a banjo player and singer from Eastern Kentucky. John Cohen — a documentary filmmaker, photographer, and musician from New York — made several recordings of Holcomb in the 1960s, including “Swanno Mountain.” Holcomb claimed to have learned it from North Carolina lumbermen. Taken together, these examples provide evidence that, by the end of the 1960s, a combination of factors involving the efforts of song collectors, recordings by folk revival artists, and regional performance practice mostly stripped “Swannanoa Tunnel” of its powerful legacy as an African American work song and cautionary tale.

Since the 1960s, performances of “Swannanoa Tunnel” have continued to appear on commercial recordings released by white artists active in folk, old-time, bluegrass, and related genres. The latest high-profile example came from Bryan Sutton, a three-time Grammy winner who included it on his 2014 Grammy-nominated album, Into My Own. For white musicians and fans from the area, the collective memory surrounding this song’s provenance produces a vivid sense of local identity and regional pride connected to Western North Carolina. For those outside the region, it’s a generic musical memorial of industrial danger and human resilience. Such misremembering persists because Black artists are missing from the corpus of issued “Swannanoa Tunnel” recordings.

When you hear that

Hoot owl squawling,

Somebody died.

Somebody’s dead.

In this kind of research, academic discographies are a gold mine. First published in 1964, Blues & Gospel Records 1890-1943 is considered “the Bible” by collectors and researchers of pre-war recordings by Black performers. It lists commercial releases as well as so-called field recordings. Upon learning the real story behind “Swannanoa Tunnel,” we checked for references. There was one listing under an alternate title: “Asheville Junction” by Will “Shorty” Love. Duke University folklorist Frank C. Brown had recorded Love in 1939. Brown’s description of Love as a “colored janitor for many years” on Duke’s East Campus intrigued us for its inadequacy and its implications. Aside from being a performance by a Black man in North Carolina, this recording was quite old. Few versions predated it.

The Library of Congress held the recording, but it had never been issued. We checked with staff at Duke’s rare book and manuscript library about the audio material in its Frank Clyde Brown Papers. Sure enough, they had the original phonodisc, and it had been digitized. This is no small matter. Field recordings from the early-20th century are often trapped on fragile wax cylinders or brittle lacquer discs that require elaborate technology to digitize them. After several emails and a $5 reproduction fee, we had a digital copy of Love’s “Asheville Junction.” The arrival of the MP3 attachment was ordinary enough, but the sound file proved extraordinary.

Love’s rendering bears all the hallmarks of a classic hammer song. He sings unaccompanied and pounds on something nearby — perhaps a table — to mimic the hammer blows of hard labor. His exertion is audible at one point, as if he’s actually driving steel. His melody and lyrics are redolent of other performances. (Love’s verses are the ones that appear throughout this article.) Love’s singing, however, is distinctive, stark and unadorned. It sounds nothing like the versions we had heard before. We needed to learn more.

It was easy to learn about Dr. Frank C. Brown, a white man who left behind a collection that a fellow scholar called “the most imposing monument ever erected in this country to the common memory of the people of any single State.” Brown taught courses on Shakespeare and English literature at Trinity College, played a central role in managing Trinity’s expansion into Duke University in 1924, and spent decades collecting tens of thousands of items pertaining to North Carolina’s folk heritage. He was instrumental in the formation and activities of the North Carolina Folklore Society, one of the oldest in the nation, and he joined British and Irish folklore societies as well. Following Brown’s death in 1943, Duke compiled his enormous collection of materials into seven massive volumes, a herculean task that required an editorial board of over 10 scholars.

Will “Shorty” Love’s voice is preserved in the American folk music canon thanks to Brown, but Love’s presence, in part, is a representation created by Brown’s scholarly (white) mind. Put another way, if not for Brown’s interest in cataloging folk practices then Love would not be part of this story, but the representation of culture that Brown endorsed warrants scrutiny. Benjamin Filene’s Romancing the Folk explores this idea, writ large, through profiles of cultural “middlemen” who romanticized “the folk” in their documentary work. Woven throughout Filene’s book is the father-son team of John and Alan Lomax, two white men who “discovered” Black musicians such as Huddie Ledbetter — professionally known as Lead Belly — and Muddy Waters.

There are notable connections and parallels between John Lomax and Brown. Contemporaries in age, they made folklore into something more than a sub-discipline of English, and in this spirit, Lomax encouraged Brown to organize the North Carolina Folklore Society. Both approached fieldwork with missionary zeal. They loaded their car trunks with portable recording equipment, weighing hundreds of pounds, to document the sounds everyday people made in their home communities, or what scholars refer to as “the field.”

Fieldwork can mean a lot of different things. Lomax sought out southern prisons to collect “pure” material from incarcerated Black men, believing that “convicts heard only the idiom of their own race.” Brown traipsed through the Carolina backcountry, risking — on account of his dapper outfits — being mistaken for a revenue agent. Unlike Cecil Sharp, these men collected songs from a diverse array of communities on principle, but they saw their subjects as exotic. The American folk music canon would be paltry if not for the brazenness of such collectors. They lived for awkward encounters wherein they exercised, consciously or unconsciously, tremendous social advantages. These collectors stepped up to the folk and asked, “Will you sing for me?”

Brown and Love had many such encounters. Brown made written transcriptions of Love’s singing in the early 1920s, but their only audio recording sessions occurred in 1939. At the first session, Love recorded only “Asheville Junction.” The following month, Love sang seven more songs, mostly sacred in nature. The recordings themselves convey little beyond the music. Love laughs at the conclusion of a couple of them, but there are no spoken words on the phonodiscs. Surely the men had a rapport, but all of that is lost to the record.

Several of Love’s melodies and song texts appear in the multi-volume anthology of Brown’s folklore, but “Asheville Junction” does not. The editors mention it only to say that it “does not differ in any significant detail” from a version Brown collected from Lunsford in 1922. While there’s no audio from 1922, this claim is suspicious considering how different Love’s version is from Lunsford’s subsequent recordings. When the collection does cite Love as a source — at least 15 times — it occasionally identifies him as a “Negro,” and always as a janitor.

James William Love, 1876-1963, worked at Duke University for 44 years. In 1939, Duke University folklorist Frank C. Brown recorded Love singing “Asheville Junction,” the only known recording of a Black person singing the song.

It was difficult to learn about Will “Shorty” Love, a Black man who worked in interwar Durham, North Carolina. Internet searches through social security records yielded more than 1,200 people with the name William Love in 1920. Searching within these for the words North Carolina, as well as cross-referencing to exclude people with death dates before 1939, winnowed our search to three men.

At this point, our hunt for answers blossomed into a group effort. A colleague who studies genealogy narrowed our list to one person, and produced his WWI draft card and death certificate. The documents identified Love’s occupation as “janitor” and his stature as “short.” He was 86 when he died in 1963, which meant he was a teenager when the WNCR’s construction ended in 1892. Another disturbing wrinkle emerged from the death certificate. Love had died of malnutrition and exposure; his frozen body had been found in the woods on the outskirts of town in mid-January.

We called Duke’s human resources department to see if they might have a file on a janitor from 80 years earlier, and a befuddled receptionist referred us to the university archives. Ironically, this put us right back where we’d started. Thanks to a helpful archivist, we soon had a set of documents about Will “Shorty” Love that reminded us of a central lesson we’d learned in researching the Swannanoa Tunnel: there’s a gulf between white perceptions and Black realities.

Brown left a thin record of his meetings with Love, but the two men’s relative positions at Trinity, as conveyed by documents in the archives, suggest plenty. Brown had power. When Trinity College transformed into Duke, he selected the stone for its iconic chapel. He also traveled with Trinity President William Preston Few to approximately 20 different elite institutions, weighing architectural and landscaping options for Duke’s new campus.

Love, on the other hand, had a different relationship with the president. A 1919 typewritten letter to Few from the Trinity “juniters” makes a harrowing appeal for a raise on the grounds that “ouir,sary,dose,not,cover,our,in,debtness.” They conclude, “please,raise,ouir,sary,if,you,please,sir we,hope,that,you,will,not,forget,us.” One can assume the song collecting encounters between Love and Brown were fraught with inequality.

When modern archivists became aware that Brown and other song collectors rarely shared their field recordings back with the marginalized people from whom they collected them, some began a practice of repatriating recordings. Our correspondence with the Duke archives led us to Dr. Trudi Abel, an archivist who had repatriated recordings to Will “Shorty” Love’s descendents. On account of a minor error in Duke’s database, she had shared all of Love’s songs with his family except “Asheville Junction.” Thanks to Dr. Abel, however, we had contact information for Clarice Thorpe, Love’s 87 year-old granddaughter who still lives in Durham. Thorpe’s niece Valerie Gill graciously organized a visit and shared that her aunt was excited to meet with us to talk it all over.

I’m going back to

Swannanoa Tunnel.

That’s my home, babe.

That’s my home.

Drone footage by Nolan Swoap

The most direct route from Swannanoa to Durham remains the Swannanoa Gap, where Interstate 40 cuts through. We sensed the tunnel passing beneath us as we headed toward the Piedmont and our meeting with Clarice Thorpe. A few hours later, we pulled into the lot below her Durham apartment building. Clarice Thorpe’s nephew, Tim Thorpe, and his daughter Kiara Thorpe met us at the building’s entrance. Gill would also be coming, and they had plans to have Clarice Thorpe’s cousin Ruby Adams (another surviving granddaughter of Love) join us on speakerphone from Florida.

We all walked down a third-floor hallway until stopping at a door with a handwritten sign in red lettering:

Notice — Please Do Not Ring My Bell To Borrow —

Thanks.

"Christ Is The Answer."

Inside, the apartment was cozy. As we found our seats, Clarice Thorpe entered the living room. She was petite, carrying an overstuffed scrapbook that she called the “family book.” Once we had introduced ourselves, Ms. Thorpe immediately unfolded the book and began filling the room with rich anecdotes about her “Grandpapa” Love. As we sat and listened, a wholly different story emerged before us.

James William Love was born in 1876 and settled in Durham in the 1890s. He began working at Trinity College around 1905 and retired from Duke after 44 years of service. The family members were surprised to hear about sources identifying him as a janitor. His granddaughters explained that he had been a mail carrier for the bulk of his career, serving the female dormitories on the East Campus. He was a caring man who sometimes referred to the students as his “daughters.” Through his friendships with them, he became conversant in three languages, including Yiddish and French. Love’s formal schooling stopped after seventh grade, but he read three to four newspapers a day.

“I’d never seen Grandpapa in a pair of overalls or dungarees. Never in my life,” Clarice Thorpe said at one point. “Most every time you’d see him he was in a suit.” He sported a Stetson fedora. “Always tipping his hat,” she said. Love was a middle-class, family man who purchased his own home around 1912 and owned a Model T. A deacon at his local church, he loved to sing sacred songs. He also pushed back against the status quo. When a police officer questioned Love about his driver’s license and threatened to ticket him, Love defended himself and his record. “I have never been to jail, and I’m not going to jail,” Clarice Thorpe recalled him telling the officer, who issued a warning instead.

We had imagined Love dying of exposure because of poverty, but the real Will Love had died, in part, due to his distrust of the police. He was a peripatetic man who preferred to walk everywhere. In retirement, Love walked miles to visit former neighbors at the only Durham nursing home for Black people. Love’s daughter - Clarice Thorpe’s mother, Bessie Thorpe - worried over him after he got lost one time; his mental health was in decline. This gave rise to another encounter with the police when they offered him a ride and he refused. The police threatened to put him in jail if he didn’t start listening to his daughter. Love had begun to lose his mind, but he stuck to his principles of independence. One January afternoon, he set off on foot from the nursing home, lost his sense of direction, and never returned. Hunters found his body in a makeshift shelter nine days later — frozen stiff in his tailored suit.

As we turned to explain the recording, we recounted our excitement at finding a listing for Will “Shorty” Love. “Shorty?” wondered Tim Thorpe. “Well, he was short.” Clarice Thorpe also seemed puzzled. Although this nickname appeared throughout writings by white scholars, it was unknown to his family. Clarice Thorpe corrected us. “Everybody called him Will,” she said. “I never heard nobody call him ‘Shorty.’”

“Shorty” the janitor faded as our visit wore into the evening, and in his place, the real Will Love emerged. A respected man with a formidable intellect, caring nature, and a talent for music, he resisted power structures, petitioning the president of Trinity College for a raise and defending himself against police mistreatment.

According to Clarice Thorpe, Love’s history with the police was shrouded in general disdain. “Something must have happened in Grandpapa’s life,” she said. “I don’t know what it was.” Yet the outcome was certain. “He didn’t like police! I’d say, ‘Grandpapa, police are alright. Police are there to protect you.’ ‘No, they’re not. No, they’re not,’ he would say.” She recalled that her grandfather kept a loaded shotgun behind his bed in case he needed it, but mostly for protection from the police and white people. “He didn’t like the police because he knew the police would lock up Black folks.”

Tim Thorpe was shocked to hear that workers dragged a locomotive over a mountain. “I can’t even imagine the amount of force it would take to move a train across terrain!” he said. “I can’t even imagine the thought of that!” He pondered the connection between Love, the tunnel, and the recording. “Could Great-grandpapa possibly have been taught this song by a family member?”

Clarice Thorpe offered her theory, “I think it was one of Grandpapa’s brothers. That’s where I believe it came from. I really think so.”

Her nephew wondered, “What’s the connection to our great-grandfather?” Then he turned from the oldest person in the room to the youngest, his daughter Kiara Thorpe: “To your great-great-grandfather. That’s the big mystery.”

Kiara Thorpe had been listening closely. When she spoke up, she started brimming with ideas, making connections between slave spirituals, Jim Crow abuses, work songs, and her life today as a graduate student at Vanderbilt University. “I’ve been working with the National Museum of African American Music in Nashville,” she said casually. We turned the recorder her way. “And with the earliest exhibits they have, they talk a lot about how Black folks didn’t want to have their voices recorded, so I think that this idea of ‘feather-bed resistance,’ as Zora Neale Hurston talks about, of preserving culture or songs like that for your community — that may be another reason behind why it wasn’t recorded [by Blacks] before William Love.” Her words energized the room. Shortly afterward, everyone left but us. Clarice Thorpe invited us to stick around, and we chatted about her family until well past ten o’clock.

Photos of William Love and his daughter Bessie Thorpe (Clarice Thorpe’s mother), taken at their home on Englewood Ave., Durham, North Carolina. Published with permission from private family collection.

Our drive home was a flurry of dialogue. We reflected on being present as a family listened to an ancestor sing into the room, and we discussed the complexity of this song. We remembered what Kiara Thorpe had said, and Googled “feather-bed resistance.” The search yielded passages from Hurston’s 1935 autoethnography Mules and Men. She wrote these words not long before Love sang “Asheville Junction” for Brown:

Folklore is not as easy to collect as it sounds. The best source is where there are the least outside influences and these people, being usually under-privileged, are the shyest. They are the most reluctant at times to reveal that which the soul lives by.

Instead, Hurston continues, Black people “smile” and offer something ”that satisfies the white person because, knowing so little about us, he doesn’t know what he is missing.” This “feather-bed resistance” lets the folklorist’s “probe” enter, “but it never comes out. It gets smothered under a lot of laughter and pleasantries.” Hurston explains further:

The theory behind our tactics: “The white man is always trying to know into somebody else’s business. All right, I’ll set something outside the door of my mind for him to play with and handle. He can read my writing but he sho’ can’t read my mind. I’ll put this play toy in his hand, and he will seize it and go away. Then I’ll say my say and sing my song.”

We sat in silence. Were we, like Brown before us, “trying to know into somebody else’s business?” Were we handling something “outside the door” of Love’s mind? Or had our trip been something different?

Upon listening to the voice of her Grandpapa Love, Ruby Adams had said, “Somebody had the intent for this to be discovered at some point. I really do believe that this was not just coincidental. I think it was really, specifically, done on purpose that someone, someday, would discover what these people went through.” She commented on the song’s beauty and function before driving home her point. “They stuck together until the very last end. And I really believe that that may be a message that they were really trying to leave.”

We climbed toward the Swannanoa Gap, switched on the radio, and heard the news that Covid-19 had arrived in North Carolina. But we kept up our conversation. What had been an eight-year journey, we felt, had reached a terminus. The answers to our questions weren’t straightforward, but our investigation felt complete.

As we reflected on the lost lives commemorated in “Asheville Junction” and how they still lacked a proper honoring 140 years later, little did we know that a great reckoning was just around the corner.

Kiara Thorpe’s observation regarding Hurston kept ringing in our ears. We settled on an interpretation for that as well. By way of his great-great-granddaughter, James William Love had just tipped his hat.

Hammer falling

From my shoulders

All day long, babe.

All day long.

Kevin Kehrberg, musicologist, and Jeffrey A. Keith, historian, met in graduate school at the University of Kentucky, where they both earned doctorates. As graduate students, they founded the University of Kentucky String Band ensemble and learned to sing "Swannanoa Tunnel" before they even knew where Swannanoa was. Now both of them teach at Warren Wilson College, located in the Swannanoa Valley east of Asheville, North Carolina. This project emerged from a team-taught course they offered on work and music in Appalachia back in 2012. As part of that class, the two sought out a kudzu-covered trail east of town that snaked down to active train tracks, and they looked up a handful of state records about the tunnel's construction. The rest is in the article.

All drone footage by Nolan Swoap

All payment for this story will be donated to the South Asheville Cemetery Association and Building Bridges of Asheville.