When we arrived at the Ark Encounter, just a few minutes after it opened for the day, the parking lot was already full. We sat and watched families wander from their cars — many with license plates from Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin still crusted in ice and salt — to purchase tickets and board buses that would shuttle them to the ark.

My husband and I had been in high spirits on the hour-long drive from Louisville, listening to music and pointing out bands of deer grazing in the fields on either side of the highway. Northern Kentucky is a landscape of in-betweens: not quite hilly or flat; neither wholly southern or midwestern. The land itself, in mid-February, seemed to hover between seasons: the yellow winter grass was crisp with frost, while the morning’s sun was so warm I didn’t need a coat.

A 500-foot-long replica of Noah’s Ark might seem strange anywhere, but this monument to certainty felt especially out of place in this particular place, where nothing seemed quite settled. In the parking lot, a stony silence settled over us as we watched large families — some wearing suspenders, trim white bonnets, or long denim skirts — climb out of their minivans and church buses and stretch their limbs.

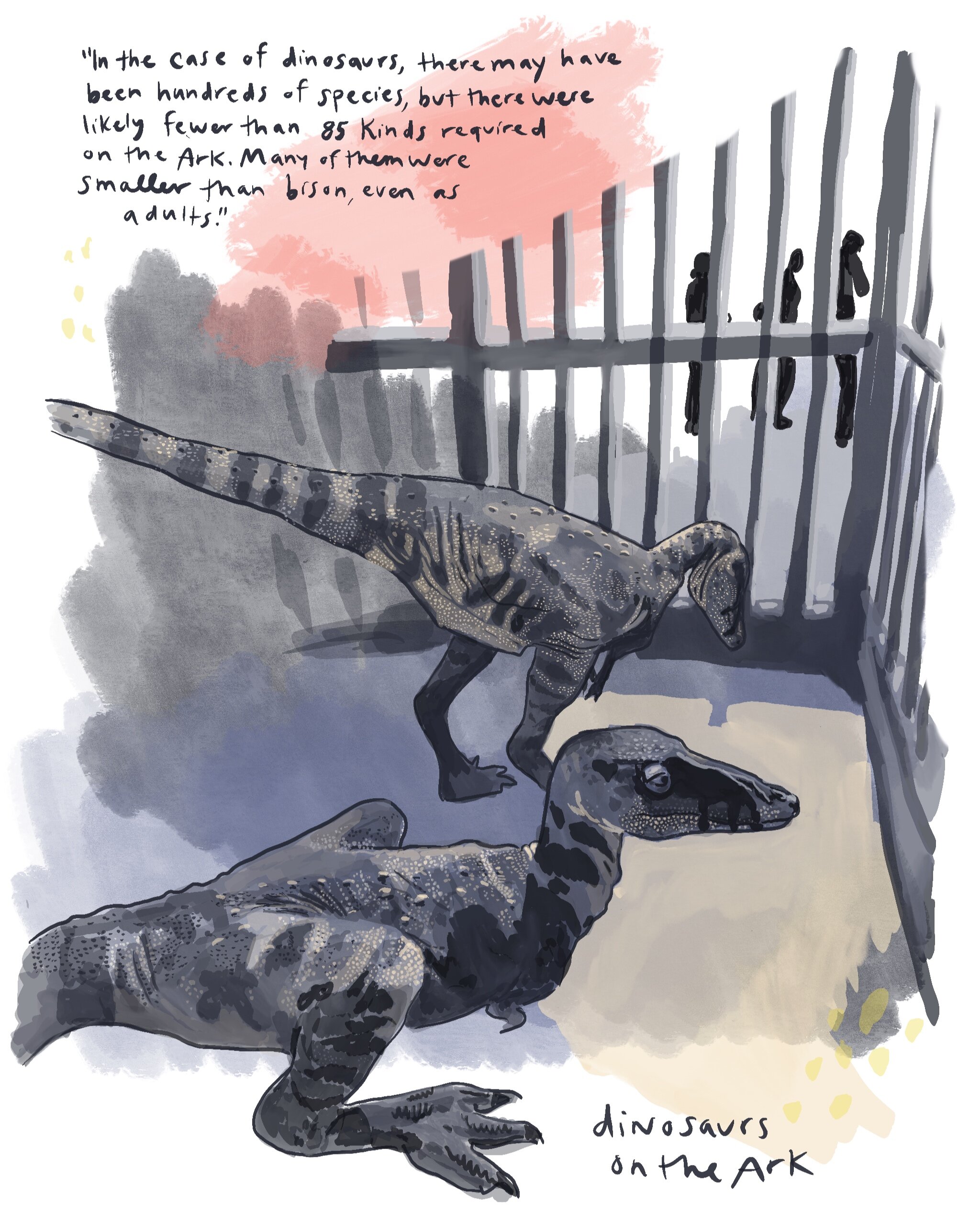

The night before, we’d stayed up late on strange corners of the internet, watching vlogs: groups of atheists debriefing in the parking lot after touring the ark, or Christian families with five or seven or nine children taking pilgrimages to the ark, traveling in hulking vans across several states. We read reviews in which even the believers complained of the ark’s too-small signage, confusing layout, and the $10 parking fee. One reviewer noted that “it was odd to see dinosaurs on the ark.” Another said, "Christians will want to spend a lot of time here.” Everyone loved the buffet.

When we finally exit our car and board the bus, the music piping through the speakers sounds eerily similar to the theme song from The Hunger Games. The bus passes through the shadow of what I think are guard towers, like those looming over prison grounds, until I realize they are stations in a zipline that sweeps visitors over the forested, gentle hills. The bus drops us off at the gift shop and we walk the winding pathway toward the boat. This is the “encounter” emphasized in the attraction’s name; the ark itself is hidden far from the road, so that when you see it clearly for the first time, you are arriving on foot, as if you’re one of the lucky few allowed to board the boat before disaster comes. This set-up — including the parking fee and tickets purchased in the parking lot a bus ride away — also ensures people won’t be able to drive by the ark to gawk or take photos for free. By the time you make it to the ark, you and your fellow visitors have been vetted; you can be sure you’re all here in good faith.

Except that I wasn’t. As the daughter of a Methodist preacher from Memphis, I’ve always been fascinated by evangelical Christianity: its newness, its certainty, and its urgency all seemed so foreign from the quiet, painfully moderate tradition I’d been raised in. My husband, Colin — a native Kentuckian who was raised in an evangelical church housed in a former shopping mall — nearly broke out in hives when I asked him to visit the Ark Encounter with me.

We’ve both drifted from the faiths of our childhoods, but as I’ve lost my footing in any particular tradition, I’ve cultivated a growing obsession with religion in general. It would be easy to dismiss this massive boat as an extreme but essentially goofy version of white conservative evangelical Christianity, but I felt determined to suspend my own judgment, to try and discover whatever it was that appealed to the people all around us, cheerfully making their way toward the boat.

The Ark Encounter is operated by Answers in Genesis, a young- earth creationist organization led by Ken Ham, who moved to the United States from Australia in 1987 to work for the Institute for Creation Research. Answers in Genesis, which he founded in 1994, also operates the Creation Museum, forty-five miles away, in Petersburg, Kentucky. The goal of the Creation Museum and the Ark Encounter is to promote young-earth creationism and a literal interpretation of the Bible and, ostensibly, to make a lot of money: the $73 million Ark Encounter opened in 2016 with the help of $18 million in state tax incentives, despite requiring employees to testify to their Christian faith on their hiring paperwork.

The Ark Encounter and the Creation Museum have quickly become the largest tourist attractions in the area, and their closest competitors are vying not just for crowds but for distinct worldviews. This area of northern Kentucky — as well as bands of southwest Ohio and southeastern Indiana — are home to the Cincinnatian fossils, dating back more than 443.7 million years, and the map surrounding the Ark Encounter and the Creation Museum is studded by fossil parks, fossil outlet stores, geology museums, and art galleries specializing in “geo rarities.”

Depending on which roadside attraction you choose, you’ll be presented with opposing visions of the world: one in which the world is billions of years old and the product of constant, ongoing change; and another in which the world is 10,000 years old, at most, and was created in only six days. In this second worldview, evolution remains, at best, just an unsubstantiated hunch, an improbable inkling. At worst, according to Henry Morris, one of the founding fathers of young-earth creationism, evolution is a “tool of Satan to destroy belief in God” and “the root of atheism, of communism, nazism, behaviorism, racism, economic imperialism, militarism, libertinism, anarchism, and all manner of anti-Christian systems of belief and practice.”

At the opening of the Creation Museum in 2007, Ken Ham referenced the 1925 Scopes trial and promised that the Creation Museum would serve as a reversal to the humiliation suffered by creationists when Clarence Darrow grilled William Jennings Bryan on the stand. The Scopes trial “was the first time the Bible was ridiculed by the media in America,” Ham said, and made a promise: “We are going to undo all of that.” In the Creation Museum and the Ark Encounter, Ham aims not only to rewrite history, but to create a future in which modern science is suspect and creationists are no laughing matter.

The writer Meghan O’Gieblyn, a former young-earth creationist, described Ken Ham’s projects as “the church’s latest attempt to bewitch unbelievers with glitzy multimillion-dollar productions.” As we approached that giant ship, its smooth wooden sides faded from four land-locked years in direct sun, I wondered whether I might find myself sympathetic, or even susceptible, to anything I found inside.

We enter through the belly of the boat, into a dark room filled with empty wooden cages stacked from floor to ceiling. There is little signage and no clear direction in which to travel, so we all wander aimlessly, looking up at the ship’s organs, the dimly lit lanterns hanging from the wooden beams overhead. Sounds of a storm at sea roar through the speakers — thunder cracking at surprising intervals, waves crashing against the side of the ship, people moaning, animals crying out, the wooden boat itself groaning under the strain of the storm. In the midst of it all, we come across an animatronic version of Noah’s family, mid-prayer, fallen to their knees.

“Noah, that’s my name!” exclaims one kid, who we will come to find is one of many children named Noah running around this boat.

In the second room, the cages are larger, and filled with unmoving replicas of each animal “kind” — the signs are careful to avoid using words like “species” that sound overtly scientific. As we trudge in a single-file line past the cages, people hold their cell phones up to the wooden bars and take photos of the animals, with their plastic sheen, sitting unmoving in their dark cells.

According to the Ark Encounter, the 6,744 animals on board included “up to 85 kinds of dinosaurs.” The Ark Encounter argues that the location of fossils discovered throughout the Earth’s substrata tells us nothing about their age, or the eons that scientists claim separated them; instead, these remains are located wherever the floodwaters deposited them as they swept across the Earth’s surface and retreated. Dinosaurs did not evolve over time, with different species existing in distinct eras separated by millions of years; they were all created on the same day, and most of them perished in the flood or were wiped out by humans after Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden. Before then, dinosaurs had coexisted peacefully with humans; it was only after Adam and Eve sinned that dinosaurs and humans began to have trouble. In one video — which a boy ran past and pronounced boring! — Adam is seen cuddling a brontosaurus.

The boat was built using dimensions taken from Genesis: 300 cubits translated to 510 feet; the exterior of the boat was constructed with a mix of cypress and pine. This is one of the strengths of the story of Noah and his ark for proponents of Biblical literalism; the story comes with specific measurements, precise numbers of animals, and exact amounts of time, that make this kind of replica possible. But in their emphasis on recreating the ark — simply to prove it was possible to fit two of every animal “kind,” as well as Noah’s family, onto a single vessel — the creators of the Ark Encounter reduce the story to its barest details, draining it of any larger significance.

I wondered whether finding any greater symbolic meanings in this story — like those I apprehended as a child learning a less-than-literal interpretation — might actually be counterproductive to the mission of the Ark Encounter’s creators: perhaps the ark might be simply a multi-million-dollar cacophonous production, full of sound and fury, but ultimately meaning nothing at all.

Behind us in line, a small boy stared at a pair of Scutosauruses cowering in their dark cell. He asks his mom, in a small, worried voice, how all these animals survived the flood. His mother seems genuinely stricken, overcome, with her hand over her mouth and her eyes wide and shiny.

“How did God even survive?” she asks him in response.

Perhaps this kind of sensory dramatization, itself, is the point: the Ark Encounter allows us to stand in Noah’s rope sandals, walk around his dimly-lit boat, and try to imagine experiencing a storm of such magnitude that it gave us the “biblical proportions” by which we now classify weather events that once seemed extreme and rare. We wander the ship’s bowels, listening to the recorded waves crashing all around us, and wonder what it would be like, to feel so much fear, and to have so much faith.

By the time we make it to the second “deck” — a little brighter and a little quieter — it takes me a full minute, staring at a llama whose ears rotate precisely from side to side, to discern that the animal is real, and not an animatronic replica. Other than this single corner reserved for a strange mix of live animals — two llamas, a tortoise, and a porcupine — the rest of the second deck is occupied by the same unmoving animal statues as the deck below.

The cages are large, and filled with “kinds” of animals I’ve never seen before — strange-looking super-sized bears (which I would be tempted to describe as “prehistoric,” even though there is no such thing, according to young earth creationism) towering alongside miniature hippos — but these cages take up only the center of the ship. Surrounding the cages are museum-like exhibits on the fall of man, the dangers of children’s book depictions of the ark, and how the women that Noah’s sons married would determine the various ethnicities of the world. It is clear that we are transitioning from the purely sensory and arriving at the meat, the message.

In an exhibit titled “Descent into Darkness,” dioramas show scantily-clad women dancing around bonfires, or men battling giants and dinosaurs in gladiatorial rings, surrounded by jeering crowds. Above us, a message printed in capital letters runs the length of the exhibit: “THE PRE-FLOOD WORLD WAS EXCEEDINGLY WICKED AND DESERVED TO BE JUDGED…DOES OUR SIN FILLED WORLD DESERVE ANY LESS?” We are meant to see our own world reflected in this fallen one, a world deserving of pity, if not punishment.

I watch as a father lifts his toddler into his arms and holds him close to one of these dioramas, in which tiny and incredibly realistic people are contorted with all kinds of suffering. The child starts crying, burying his face in his father’s shoulder.

“Look,” the man says, rotating his body so that his child will again face the diorama, “Daddy wants you to see.”

By the third floor, the animals disappear, and we wander through a rapid-fire re-writing of natural history. The Ice Age exhibit I’d wanted to see is closed to the public for “defrosting,” but other exhibits expound on evolution, carbon dating, and the age of the earth, contrasting “the evolutionary worldview” with “the Biblical worldview.” One exhibit asks how “evolutionists” and “creationists” can consider the same evidence and come to different conclusions: “Our conclusions are strongly influenced by our worldviews,” the sign argues, “Which worldview makes better sense of the evidence?”

This phrasing dismisses scientific discoveries as mere confirmation bias, while another panel suggests that scientists ignore evidence selectively, just to spite Christians: “…nearly every geologist would appeal to a global flood to explain many of Earth’s features if the Bible had never mentioned such an event.” In this line of thinking, knowledge itself begins to look polarized; scientific discoveries are merely the result of ideological camps reverse-engineering their findings, bending evidence to their will, to further their own worldview and destroy those with whom they disagree.

In the early years of the 20th century, conservative Christians became increasingly suspicious of the modernism and liberalism they saw all around them: the country was becoming more diverse, and more concentrated in cities; other protestant denominations were accepting evolution; even the authorship of several books of the Bible had come up for debate. Between 1910 and 1915, conservative theologians published a series of pamphlets titled The Fundamentals, defending tenets like Christ’s virgin birth, the inerrancy of the Bible, and Christ’s impending return to Earth.

But the Scopes trial of 1925 was a particularly galvanizing moment for white evangelicals who felt increasingly alienated: “The ignominy surrounding the Scopes trial convinced evangelicals that the larger culture had turned against them,” Randall Balmer writes in The Making of Evangelicalism. Evangelicals “responded by withdrawing from the culture, which they came to regard as Satan’s domain, to construct an alternative universe, an evangelical subculture.”

These first subcultures included Bible colleges, publishing houses, and seminaries, but soon expanded beyond the explicitly religious realm. In The Anointed: Evangelical Truth in a Secular Age, Randall J. Stephens and Karl W. Giberson describe the growing (and increasingly lucrative) “parallel cultures” of the contemporary evangelical world: in addition to Christian music, books, and movies, evangelical leaders and organizations produce “in-house versions of natural science, history, social science, and views of the end-times.” The efficacy of these parallel cultures enables evangelicals to “reject the non-Christian world around them.” In a 2010 speech, Ken Ham echoes this sense of a definitive binary, arguing that there was “no neutral position” between biblical literalism and atheism.

Some refer to this thread of conservative evangelical Christianity as “anti-intellectual,” but this doesn’t seem totally representative of the way the Ark Encounter appropriates the trappings of science while rejecting the actual findings of science. Beyond the walls of the Ark Encounter, creationists have established their own parallel cultures in the form of peer-reviewed journals and research institutes seeking to prove their theories about creation and the age of Earth. It was surprisingly unsettling to see the familiar setting of the natural history museum re-appropriated in order to undermine scientific knowledge. But it is a specific understanding of science on display at the Ark Encounter, a version of science that is adversarial, that seeks to prove, explain, and dismiss, rather than to probe, question, and describe.

Wandering the Ark Encounter, I can’t help but think about the fact of its timing. As global temperatures and sea levels rise, the future is increasingly uncertain. Many scientists can’t agree on the specific effects of climate change — can we stave off the worst effects by capping temperature rise at 1.5 degrees Celsius, or will 2 degrees be enough? Will oceans rise globally a certain number of inches, or feet? Will we lose all of Boston to rising seas, or just select streets? At the Ark Encounter, none of these questions exist. The rising temperatures we see now are either overblown, or part of the natural fluctuations the planet has seen, in cycles, over the course of its 10,000-year existence. Plus, God promised never to flood the Earth again, so we shouldn’t worry too much about rising seas.

Over the past few years, there’s been a deluge of anxious writing about how to win over the other side; how to convince climate change-deniers of the scientific facts; how to persuade Trump voters that they’re voting against their own interests; how to convince your racist uncle to be less racist. But Yale professor of law and psychology Dan Kahan writes that the facts are only one part of the conflict at hand: “We are, in one sense, only arguing about ‘facts’ — Is the earth heating up or not? Does allowing individuals to carry handguns in public increase crime or protect us from it? — but in another sense, we are arguing over something much more basic: whose cultural cues are valid, whose cultural authorities know what they are talking about, whose group is competent enough and entitled to respect and deference and whose is out of touch and contemptible.”

When I first heard of Ham and Answers in Genesis, I was struck by the insistence on “answers” in all official titles and materials. The Ark Encounter gift shop houses a sleek auditorium called the Answers Center, where Ham and a rotating cast of characters give talks — recorded for the Answers in Genesis podcast and re-printed in Answers Magazine — on subjects like “grace not race relations” and “the forensics of God’s fingerprint design.” The tagline at the bottom of articles on their website reads, “Don’t Just Wonder. Get Answers.” At a time when answers seem hard to come by, Ham is eager to give the people what they want.

One Sunday morning, a couple years before our trip to the Ark Encounter, Colin and I visited his parents’ nondenominational evangelical church in western Kentucky, where the preacher announced he was beginning a sermon series on Genesis and evolution. He described the three perspectives he would be exploring more in the weeks to come: those that believe in the science of evolution and saw the Bible as a myth; those that believe that creation was likely a mix of the scientific understanding of the earth’s origins and a metaphorical understanding of Genesis; “And the one most everyone in this room will be familiar with,” he said, “young-earth creationism, which says that the earth is somewhere between 6,000 and 10,000 years old.”

The preacher didn’t spend much time elaborating on young-earth creationism that day — ostensibly because it was the most prevalent of the three belief systems he mentioned — but this casual reference seemed to hang in the air over our heads for the rest of the service. After church, we got lunch at a pizza place a few steps away from the banks of the Ohio River, where locals passed the afternoon hours in a plaza named for Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. McConnell has represented Kentucky in the U.S. Senate since he was first elected in 1984, despite his consistent unpopularity in his home state.

The Ark Encounter, similarly, encompasses more ironies than can be named. That a monument to young-earth creationism exists alongside ancient fossil deposits encapsulates some of them. That the roadside attraction famous for denying human-made climate change sued for $1 million in property damage, following unseasonably heavy rains, gestures toward a few more. But the fact that the Ark Encounter opened the same year that Donald Trump was elected president, with the help of the white evangelical voting bloc, highlights perhaps the most essential irony of the Ark Encounter: its mission is not religious at all, but political.

The Ark Encounter celebrates a culture in which experts are referred to in quotation marks, where knowledge stemming from any source other than a single, ancient text is relative, mutable, and untrustworthy. This is conceived as being apart from the world — being from it, but not of it — and it manifests in larger trends like Christian homeschooling, the anti-vaxxer movement, and the Christian right’s willingness to support a president who shares none of their purported values.

Though Ham claims he chose to locate his attractions in Kentucky because of its central location to the rest of the country, he might as well have surveyed the American political landscape and planted his flag at the epicenter of Mitch McConnell’s legion of white evangelical supporters. Because although McConnell is deeply disliked in his home state, his voting record adheres to the evangelical line, and he has been re-elected five times.

In this way, something about Ham’s decision to land in Kentucky feels calculated. Though the ark seemed out of place as we drove up that morning, the more I think about it, the more Kentucky seems like the perfect home for a site of such contradictions. Perhaps the Ark Encounter is not an extreme outlier of conservative white evangelicalism, but the logical conclusion for a culture that claims to be separate from the world while remaining irrevocably tangled with the worldly forces embodied by capitalism and right-wing politics.

In The Anointed, Stephens and Giberson describe the social — not religious — argument made by young earth creationism: “that America’s worrisome slide into immorality, liberalism, and unbelief was caused by the widespread acceptance of evolution.” In the Ark Encounter, neither science nor evolution are the real targets, so much as they are a shorthand, a symbol, for the fallen world from which believers should turn away.

The strangest part of the Ark Encounter might be a series of two short films — part one shown on the second floor, and part two shown on the third. In the first video, Noah, played by a very tanned, dark-haired (apparently) white American actor, hurries to complete his ark while a storm builds in the background. A sneering British journalist, adorned in piercings and tattoos, asks Noah half-hearted, condescending questions about his project, while the sky glows an ominous green, flashing with computer-generated lightning. In the second video, set in the present-day, the same journalist visits the Ark Encounter and is so moved by a video, just like the one we’re watching now, that she converts to Christianity.

“Every year,” a man standing in for Ken Ham proclaims, “fifty million people are swallowed by this black hole called death.”

The journalist’s mouth hangs open. She’s no longer ironic, detached, or surly.

“You don’t have to get religious,” the man says, “You don’t have to change who you are…You get to trade your judgment in for [Christ’s] perfection.”

I’m struck by the formulaic presentation of what a life of faith was supposed to mean: give this, get that in exchange. And though the video showed the journalist transformed, shaken to her core by the experience of visiting the Ark Encounter, her conversion is not so much from doubt to faith as it is from fear to certainty. The video’s message seems uninspiring to the point of meaninglessness for the uninitiated, for the outsider it purportedly hopes to reach.

As we watch, I feel my commitment to stay curious, to withhold judgment, begin to crack. I’m wary of my own reaction to this place leading me to a place of certainty, a stance not unlike the Ark Encounter itself. But I am beginning to see that the Ark Encounter is not a tool for conversion, so much as a tool for confirmation. And once you’re in, the film — and the ark — promises, you don’t have to change your life. No soul-searching or good works required. You just have to sit secure in the fact that you have all the answers; wait for the end; don’t rock the boat.

I think of a claim Ken Ham made, that if people were to doubt the book of Genesis, this kernel of doubt would “eventually lead to them not believing the rest of the Bible.” This concern reveals the inherent precarity of literalism, of reducing faith to a formula: if any piece is removed, the whole thing falls apart.

Even as young-earth creationists reject the findings of science, they appropriate the logic and rationalism of science, as if through these tools they might create an airtight faith that can’t be disproved. From the inside, young-earth creationism offers a logical answer to every question. And though these answers tend to seem totally nonsensical from the outside, as long as you’re in, the world makes perfect sense.

But the theology I encounter at the Ark Encounter has been stripped of the essence of any religious experience I’ve ever known: a sense that some things are unknowable but still worth questioning; that a spiritual life takes shape within those questions that have no answers; that glimpses of the divine are always only glimpses — fleeting moments of revelation and surprise — that open not to concrete answers, but to a deeper sense of the unknown.

When I described the Ark Encounter to a friend who was raised in more charismatic branches of the evangelical church, he told me he often wondered if young-earth creationists might be defending themselves not against science, as they claim, but against the messiness of faith itself. He thought their motivation might be to contain the wild, mysterious, and contradictory aspects of faith by channeling it all into a rational, self-contained system, one that is only legible from within.

In the faith tradition I grew up in, science and religion were compatible — not competing — sources of truth. This made any tensions I felt between the world and the church negotiable, a question of my ability to hold multiple perspectives in tension, rather than choosing one over the other. But the certainty, the demands, of a more conservative theology might be a more effective tool for retention rates; I never had to choose between the world of faith and the world itself, and I’ve wondered if my ease in the world contributed to my ultimate wandering from faith. The religion I was raised in never demanded that I choose it and forsake all else, so I never did.

Ham argues that science is constantly changing with each new discovery, and so can’t be trusted; the Bible is the only source of infallible, unchanging truth: “Apart from the foundation of the Bible,” Ham argues, “we couldn’t really know anything for certain.” But certainty might be a barometer, not for the strength of one’s faith, but for its fragility. There is an amount of risk inherent to living as a person of faith in the world. Perhaps it is a comfort, then, to leave the secular world behind in favor of one that hews more closely to your own beliefs.

The widespread effects of this rejection of the world were on display, in the short weeks after we toured the Ark, when the country abruptly shut down as the coronavirus pandemic swept across the globe. One day in April, in Kentucky, just before Governor Andy Beshear was to announce updated death totals, protestors swarmed the capitol building and demanded he reopen the state. Some protesters held signs reading, “No King but Jesus.”

Reading reports of these protests, I wondered if a theology focused on individual salvation might surface in these politics, which prioritize the freedom of the individual over the health — and survival — of the collective. A week after the protests, Kentucky reported its highest-yet single day total for new infections.

Back home, watching this news unfold, I thought of our trip to the Ark Encounter, about the way that massive ship filled with people as the morning went on, and how — as we made it to the third deck — the air had gotten stuffy and warm, each exhibit packed with people standing shoulder to shoulder. I hurried past the last few exhibits, my brain weary, my body increasingly wary of the growing crowds. We squeezed past families smiling in front of green screens, posing for portraits they would purchase inside to commemorate their trip. As we emerged from the boat, new streams of visitors arrived on tour buses and poured through the entrance. Outside, we stood blinking into the sun, at this world that seemed so new and strange, like a place we’d never seen before.

Correction August 20, 2020: An earlier version of this essay used the word “tenant” where it should have been “tenet.”

Martha Park is a writer and illustrator from Memphis, Tennessee. Her work appears in Guernica, Granta, Ecotone, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. She is currently at work on a collection of essays about faith and the South.

More from The Bitter Southerner

Somebody Died, Babe

Become A Member

Support Southern Storytelling