Photo courtesy of the American Beach Museum

In 1935, Florida’s first Black millionaire, Abraham Lincoln Lewis, purchased a stretch of oceanfront property to provide “a place for recreation and relaxation, without humiliation” for African American people. Hold a conch to your ear and you might hear the ocean. Listen close to history and you might hear the whispers.

Story by Nikesha Elise Williams

True Black history is usually uncovered through the whispers of elders, telling stories in the next room, the children excised so grown folk can converse. Their whispers replicate the tradition of the griot in African cultures, though with much more secrecy and euphemized explanation, so as not to upset the racist power structure that may want to mute their whispers — or, worse, still forever the lips and tongues on which they are carried.

Whispers. That is the only way I can describe what drove me to American Beach, the little community on Amelia Island, Florida, nestled between two of the most glitzy, high-falutin’ hotels you can imagine. The Ritz Carlton and The Omni. On the drive up to American Beach on the rugged two lane highway that is Heckscher drive, pristine white sand beaches cohabitate with wetland trees, their roots rising from the water. But the untouched land does not last. The closer you get to Florida’s northernmost county, and one of its wealthiest zip codes, the more you see natural beauty altered in favor of man’s imaginative machinations. Million-dollar homes behind heavy, wrought-iron gates with posted guards, surround you on all sides of Beach Lady Highway. And then you see the white sign, diminutive in comparison to all that’s around it, that says “Welcome to Historic American Beach.”

I first learned of this beach owned by Black people from my news anchor when I worked as a producer at Action News JAX, the CBS/FOX affiliate in Jacksonville, about five years ago. She told me then she was working on a story about the community.

My second introduction to the subject was in 2017 through a book club. The group hosts a meeting at the American Beach home of Marsha Dean Phelts, who has written three books about the community. As of late, Mrs. Phelts has been working to acknowledge every port along the Eastern seaboard in which captive Africans were brought ashore, enslaved, and forced by the nature of their bondage to toil on plantations across the South.

My third introduction was through social media. I saw a picture of a friend standing in front of the American Beach sign with a caption marked “staycation.”

Three disparate connections, each whispering to me from somewhere in the saltwater depths of my creation that there was a story I did not know that needed to be told. I believe the whispers found their way to my listening ears from the realm of my ancestors. Their whispers connected me to the people at the heart of this story.

And they landed me an invitation to a gallery, for the opening of a show about the place called American Beach.

Photos courtesy of the American Beach Museum

Inside an inconspicuous and nondescript building on a rainy, February evening in downtown Jacksonville, Florida, 350 people gathered to honor and celebrate the legacy and history of “The Black Beach,” which is also the name of the contemporary art exhibition inside the Heather Moore Community Gallery. It is an in-depth visual meditation on the present condition of American Beach, Florida, the seaside community some 40 miles north of downtown Jacksonville that was founded by Florida’s first Black millionaire, Abraham Lincoln Lewis, in 1935. The feeling inside the gallery halls was electric. I was among people of all colors, creeds, identities and age ranges meandering through the corridors to celebrate history and history in the making. But the present-day collective of us — woke and conscious, Afrocentric and artistic, Black and excellent — is not where the story of American Beach begins. The story of American Beach is an American story, and like all American stories, its beginning — whether acknowledged or not — is slavery.

“Some say that slavery was our country’s original sin, but it is much more than that. Slavery is our country’s origin.”

— Hasan Kwame Jeffries, “The Courage to Teach Hard History,” 2018

Dr. Johnnetta Betsch Cole quoted those words during her keynote address — days before the gallery opening — at the 2020 Kingsley Plantation Heritage Celebration. The annual event is held to honor and recognize the history and the legacy of the plantation’s storied owner. Dr. Cole was there not only as a distinguished scholar, educator, and anthropologist, but also as a descendant of plantation owner, Anna Madgigine Jai Kingsley, or as she was known in her home country of Senegal, Anta Madjiguéne Peya Fall Ndiaye. Dr. Cole, her siblings, and their children are not only the descendants of Anna Kingsley, but also of Abraham Lincoln Lewis.

So the story of American Beach begins in Senegal. Anta Madjiguene Peya Fall Ndiaye was born in 1793, a princess in the Wolof Kingdom of Jolof. Kidnapped in 1806, at the age of 13, she survived her stay at Goree Island and the Middle Passage as the probable favorite — which earned her no favors — of enslaver Zephaniah Kingsley, who was 41. Captured and repeatedly raped, by the time Anta arrived on Kingsley’s sprawling estate in what is now present day Orange Park, Florida, she was pregnant with their first child.

Her name was changed to Anna Kingsley and she had four children with Zephaniah. She rose in prominence from being his enslaved property, to his wife and plantation manager. She ran his enterprise — powered by the labor of the enslaved — in a manner much like the Senegalese village from which she was stolen. Emancipated in 1811 she lived the rest of her life as a plantation and slave owner and Zephaniah Kingsley’s acknowledged wife, even after his death in 1843. Anna Kingsley also founded a free Black community, most of them Kingsley family members or their former enslaved laborers. This community survived until Florida seceded from the Union threatening the safety of every Black person under Anna’s charge.

One of the plantations she ran is the preserved and protected historic landmark Kingsley Plantation, on Fort George Island, situated between Duval and Nassau counties in Northeast Florida; between the ports of Jacksonville and Fernandina. Ports where enslaved Africans were brought into Spanish-held Florida and sold North to fuel chattel slavery in America after the United States made the importation of slaves illegal in 1808. The captive Africans brought into the ports of Fernandina made their way to Kingsley plantation in Duval County as well as Harrison plantation in Nassau County.

Kingsley Plantation

However, because of pirating and port inspections, sometimes the newly arrived cargo of people were thrown overboard into the Atlantic, their bodies washing up days later on the coast of Florida, in what is now known as American Beach. This too is a whisper of history: The pirating and port inspections are well documented, as is the disposal at sea of those who were captured and enslaved but did not survive the Middle Passage. What is harder to corroborate is the willful murder of captive Africans by drowning in the name of avoiding detection, followed by insurance claims for lost property.

This murky history lesson into the annals and underbelly of America’s beginning is vital to the story of American Beach because, as its denizens and defenders often note, there is magic, healing, and a certain energy in its waters. They attribute this alchemy to ancestors whose souls still speak from their watery graves to those willing to listen.

This history, that alchemy, this unexplained sequence of events is how Mary Sammis, the great-granddaughter of Anna Kingsley, became the first wife of Abraham Lincoln Lewis, and together they had one son, James Henry Lewis.

Abraham Lincoln Lewis was born in 1865 in Madison, Florida — between Tallahassee and Jacksonville — to parents who had been enslaved. His great-great-grandaughter, Peri Frances, said Lewis and his family moved to Jacksonville where they began to work in the sawmills. It was here, in the sawmills of Jacksonville, where Lewis rose through the ranks to become a foreman when he reached his early 20s.

“He had what was estimated as a third-grade education, and he was clearly brilliant and self-taught,” Frances says. And had a lot of business acumen and was a voracious reader.”

From a foreman in the saw mills, to an investor in a black-owned shoe company to the founder of the Afro-American Industrial and Benefits Association in 1901, Lewis was a natural-born entrepreneur. His benefit company, later known as the Afro-American Life Insurance Company — or simply the AFRO — was the first insurance company in the state of Florida “white or Black,” says Carol Alexander, the founding director of the American Beach Museum.

“Here’s a man in 1901 who didn’t call it the ‘negro’ insurance company or the ‘colored’ insurance company. It was the Afro-American Life Insurance Company,” Frances says, with reverence for the vision of her great-great-grandfather.

While the name of the company was emblematic of the future for Black people in America, its purpose was pragmatic. It was created so that Black people in the Jim Crow South of Florida could bury their loved ones with dignity. But the AFRO functioned as much more than a burial service. For the Black people of Northeast Florida in the early 20th century, the AFRO was what the still-segregated government should have been — a lifeline.

“The AFRO functioned as a lot of things we think of as government responsibility or social service, or social work,” Frances says. “It did those types of things when people were in crisis, or in stress, or in need of assistance.”

Abraham Lincoln Lewis had other entrepreneurial endeavors including a Coca-Cola bottling company and real estate holdings in Jacksonville, New York, and elsewhere, but there was a man behind the business.

Dr. Johnnetta Betsch Cole, Abraham Lincoln Lewis’s great-granddaughter and aunt of Peri Frances, says she and her sister, Marvyne, affectionately called him FaFa. She remembers him as a dignified man.

“An exceedingly proper individual,” says Cole, whose distinguished career included an 11-year stint as president of Spelman College in Atlanta and eight years as director of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African Art. “I cannot ever remember seeing FaFa without a tie. Now, when you wear a tie on the beach, you’re pretty proper.”

In Dr. Cole’s measured speech, she painted a picture of who Abraham Lincoln Lewis was with careful specificity — a deeply religious man whose favorite Bible verse was from the Old Testament prophet Micah.

“He has told you, O mortal, what is good; and what does the LORD require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?”

— Micah 6:8

Abraham Lincoln Lewis founded the Afro American life Insurance Company in 1901. His granddaughter Dr. Johnnetta Betsch Cole remembers him being “exceedingly proper….when you wear a tie on the beach, you’re pretty proper.” Photo courtesy of American Beach Museum

Dr. Cole recalled attending Mount Olive African Methodist Episcopal church on the east side of Jacksonville and then gathering at Abraham Lincoln Lewis’ home, where she and her sister would play. Before Sunday dinner, Lewis quizzed them on the three Bs.

“The first B is the Bible,” Cole said. The second B is the school book. And the third B is the bank book.”

Dr. Cole said these lessons from FaFa in her formative years have carried her through her adult life, reminding her of the centrality of faith and the importance of education and financial stability.

Abraham Lincoln Lewis, Cole said, “believed in education like the devil believes in sin.”

His staunch belief in higher learning led him to support Edward Waters College in Jacksonville. The college, now among the South’s ranks of historically black educational institutions, was the first of its kind in Florida. Lewis was also great friends with renowned Florida educator Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune, and later served on the board of Bethune Cookman College (now known as Bethune Cookman University), another HBCU. His commitment to service and his leadership of the AFRO led him at one point to becoming the vice president of the Negro Business League founded by Booker T. Washington.

The AFRO’s assets grew throughout the early 20th century. Even in the midst of the Great Depression, the AFRO’s assets totaled more than half a million dollars. The company was helping Black people achieve the “American Dream” in the face of oppression by helping to provide employment, home ownership, healthcare, and an elevated quality of life.

Cole believes that by reinforcing the importance of education, faith, and the power of financial independence, her great-grandfather was shaping a legacy among his loved ones to live in service to others. This legacy is evident in Dr. Cole’s own life, considering her career in education and anthropology — even if it was a departure from the family business.

“I feel profoundly grateful to have discovered anthropology because there was of course the expectation on the part of my grandfather, James Henry Lewis, who I called Papa, that I would come into the insurance business,” she says.

That spirit of service led Abraham Lincoln Lewis to search for — and make real — that “place for recreation and relaxation, without humiliation.”

In 1935 (12 years after the death of his first wife Mary Sammis), Lewis oversaw the purchase of 200 acres of remote beachfront property near high dunes, known now as “NaNa” (dubbed that by his great-granddaughter MaVynee), near the original Franklintown settlement. Franklintown was a community that arose from the formerly enslaved people of the Harrison plantation — in Nassau County — and their descendants who remained on Harrison to work in agriculture and fishing. The very existence of Franklintown paved the way for American Beach. American Beach became because Franklintown was.

Photo courtesy of Peri Frances

“We wanted a place to go where we could relax with our family, have a good time without being scrutinized, questioned, and stared at. So they would come here,” says Carol J. Alexander of the American Beach Museum.

For 29 years, from 1935 to 1964, American Beach thrived during a 20-Sunday season from April to September.

“They would come because the beaches in Jacksonville were segregated,” Alexander says. “Just like the water fountains, just like restrooms, just like us having to go to the back of the bus, we didn’t go [to] the back of the sand. They just wouldn’t let us on the beach, period.”

Black people from southern Georgia and northern Florida would caravan to American Beach. There would also be bus trips from historically Black colleges and universities. Frances says, “There were always some people who lived at American Beach, but the majority of people were vacationers.”

These vacationers returned year after year to this safe haven away from the ugly realities of lynchings, bombings, fire hoses, and domestic terrorism in the Jim Crow South.

American Beach then is comparable to Oak Bluffs in Martha’s Vineyard now. The Black glitterati and literati came to the Black beach on Florida’s pristine coastline. Zora Neale Hurston, Cab Calloway, Hank Aaron, and James Brown are just some of those who patronized the seaside resort town.

“There was a Miss American Beach beauty pageant. And for a long time American Beach was the economic engine of the south end of Amelia Island, white or black,” Frances says.

From 1935-1964 Black tourists from all over would flock to American Beach. These vacationers returned year after year to this safe haven away from the ugly realities of lynchings, bombings, fire hoses, and domestic terrorism in the Jim Crow South. Photos courtesy of American Beach Museum

Before the golf and tennis resorts that make the area surrounding American Beach upscale and exclusive, there was a community and economy of Black people built on small business, patronage, and racial pride.

Frances recalls being told of American Beach in its heyday — where there were dairies, ice cream parlors and sandwich shops all fueled by the economic activity of the Black tourists who were coming to American Beach.

Johnetta Cole, Annette Myers, and Marsha Dean Phelts lived it, and they all remember the throngs of people.

“I remember so well counting the buses and wondering how many more there could be,” Dr. Cole says. “No one was going to tell us we couldn’t be there.”

“There were hundreds and hundreds of people who would come to American Beach during the summers,” says Annette Myers, a longtime American Beach homeowner.

“It was like two things I’ve done — coming to Mardi Gras and going to Coney Island,” Marsha Dean Phelts says. “I didn’t know anything better than those two things, other than American Beach. It was my Mardi Gras. It was my Coney Island.”

Once the tourists from as far as Texas, New York, and Washington, D.C. reached American Beach, they stayed in the local motels like Duck’s or the A.L. Lewis Motel.

“To many of us it was like The Ritz Carlton,” Myers says of the A.L. Lewis Motel.

Phelts’ husband, as a teenager, worked at Duck’s, which fed and lodged caravans of tourists. She remembers him and other teenagers working almost around the clock, waking up at 5 or 6 to start breakfast, washing the breakfast dishes, cleaning the rooms, and then transitioning into dinner service.

“They had to go out, buy the supplies, get the fish,” she says. “The fish were cleaned, but the shrimp weren’t, so they had to peel and head the shrimp. And the whole time, they were cleaning toilets and emptying garbage and washing dishes.”

The call of the ocean — that desire for the feel of sand between the toes — was strong, but American Beach’s magnetism also came from Evans Rendezvous, a local nightclub.

During the opening exhibition of “The Black Beach,” the son of the owner of Evans Rendezvous told a story of when the police had to be called for “crowd control” when James Brown was scheduled to play a set at the club. Phelts doesn’t remember that particular night, but says that Evans Rendezvous “was the heartbeat of American Beach.”

Courtesy of American Beach Museum

“You might not want to go in the water, but you sho’ nuff wanted to get into Evans Rendezvous,” she says. “You just had to hang out and look in. You see a crowd coming out, a group coming out, you knew you could rush on in there.”

Warmth and a feeling of nostalgia fill the voices of Dr. Cole, Phelts, and Myers when they talk about American Beach in its prime. Their stories bring forth joy and laughter. Even for Peri Frances, who has only heard recollections of the heyday of American Beach, there is a twinkle in her eye and a tone of wonder in her voice when she recalls that reverie of Black excellence.

“I meet a lot of people in the Jacksonville area or in St. Marys and Darien who say, ‘Ooh, my grandparents used to go there,’ or ‘My mama and daddy told me about it,’ or ‘When I was little we used to go to the Black beach in Fernandina,’” Frances says.

In the midst of the Great Depression and in the face of relentless oppression, American Beach became the gathering place — one of the few places for Black people to go for rest and respite, without being questioned.

“American Beach is in the hearts of people,” Phelts says.

“An amazing and grace-filled community,” Dr. Cole says.

“It was the hotspot; it was jumping,” Frances says.

Then there was a hurricane.

Hurricane Dora developed as a tropical wave through the Cape Verde Islands near the coast of Senegal on August 28, 1964. Southern folklore suggests that because hurricanes generate off the West coast of Africa where the kidnapped first embarked on the Middle Passage, that the storms themselves are the souls of the Africans who chose suicide over slavery, were drowned intentionally, or died in the slave castles and dumped in the ocean, coming back to wreak havoc on a world that has never repented or even asked forgiveness for this most egregious sin.

My first encounter with this chthonic report was from a fellow news producer who — unlike me — was born and raised in the South, in the rural town of Ocala, Florida. When I made mention of such an embodied origin of hurricanes to my meteorologist in the midst of storm coverage during the 2018 or 2019 hurricane season, he nodded his head in agreement as he too had grown up hearing the whispers of why hurricanes develop where they do.

There were 11 days from the time of Dora’s development to its landfall as a strong Category 2 storm just north of St. Augustine on September 9.

The Jacksonville Historical Society notes, “The storm cut a path across the northern part of the state before finally making a track to the northeast on September 12. … Winds from the storm made one last return to Jacksonville about a week later as the system circulated back into the Atlantic Ocean. This time the winds were only at the tropical storm level, but they confounded the recovery efforts.”

What Dora demolished was further stymied from reconstruction because of desegregation. “Recovery efforts” didn’t reach American Beach, the Black beach.

On a visit to American Beach years after Dora had come and gone Frances recalled seeing the recovery that wasn’t.

“There were buildings you could see that still had fissures in their concrete foundation from 1964,” Frances says. “And there are places that were empty lots because the home that was there got destroyed in the hurricane and it never got rebuilt.

Hurricane Dora slams into American Beach in 1964. Photo courtesy of American Beach Museum

Ten years before Dora, the Supreme Court outlawed segregation in schools in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case. The work of the Civil Rights Movement had yet to reach its peak, but when it did — with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 Dora had come and gone and left American Beach razed in her wake.

“Things began to open,” Alexander says. “So, Black folk in Jacksonville could go to Jacksonville Beach. They didn’t have to come fifty minutes up Heckscher Drive. They didn’t come here...this thriving community became kind of dormant.”

American Beach suffered in the quest for equality and social parity.

“Once we could go anywhere, once hotel accommodations and travel opened up, people felt like that was a symbol of having arrived,” Frances says. “If you could afford to go anywhere you did. There was an exodus.”

Black people began to enjoy creature comforts closer to their actual homes, instead of traveling to American Beach, meanwhile capitalist opportunists and manifest destiny developers took to heart the infamous quote of World War II British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, “Never let a good crisis go to waste.”

The Sea Pines Company owned by Charles Fraser bought land on Amelia Island, surrounding American Beach, in 1970. By 1972 they unveiled the master plan for Amelia Island Plantation. That master plan can be seen today in the Omni and Ritz-Carlton hotels, and the million dollar beachfront homes in subdivisions. These testaments to progress came at the expense of the people who were there first.

“Fraser had this vision of these exclusive golf and tennis style resorts all along the Eastern seaboard from North Carolina to Florida,” Frances says. “They thrive off exclusivity, but they also disregard the fact that in almost every single one of those places there’s a pre-existing — either indigenous or African American — community that, in order for [the development] to succeed needs to be removed.”

Like the Gullah and Geechee people who were replaced so that Hilton Head or Saint Simons Island could become what they are today, the same logically should have happened to the residents of American Beach. But it didn’t. Today, the 11 blocks of American Beach, streets named for its Black founders, their wives, or mothers, stand defiant in the face of the upscale and opulent excess surrounding them, encroaching upon them, and insisting they give up the fight and their right to exist.

For that preservation, you must thank the remaining homeowners working to preserve their history — and the Beach Lady.

If Abraham Lincoln Lewis is the undisputed father of American Beach, then there is no denying that his great-granddaughter, MaVynee Osun Elizabeth Betsch, is its mother, its guardian angel, and its guiding link to the ancestral realm.

She was born Marvyne Elizabeth Betsch in 1935 (the year American Beach was founded). She crowned herself MaVynee Osun in the 1980s in protest of the environmental policies of Ronald Reagan.

Her niece, Peri Frances, says, “She had been in her life a former opera singer. So she was very into vibration, and notes and chords. So she made the decision in the ’80s, based upon the environmental policies of Ronald Reagan that she did not want to carry the same sound vibration as him, so she took the ‘R’ out of her name, and then she added an extra ‘E’ for the environment.”

MaVynee (Ma-Veen) chose Osun as her middle name after the Òrìsà goddess of femininity, sensuality, love, and the arts. Osun’s number in Ifá is five, which was also MaVynee’s magic number.

“She said everything is 5,” Alexander recalled.

“MaVynee was very into numerology, numbers, [and] symbols,” Frances says. “She had, like, her own cosmology, her own unique belief system.”

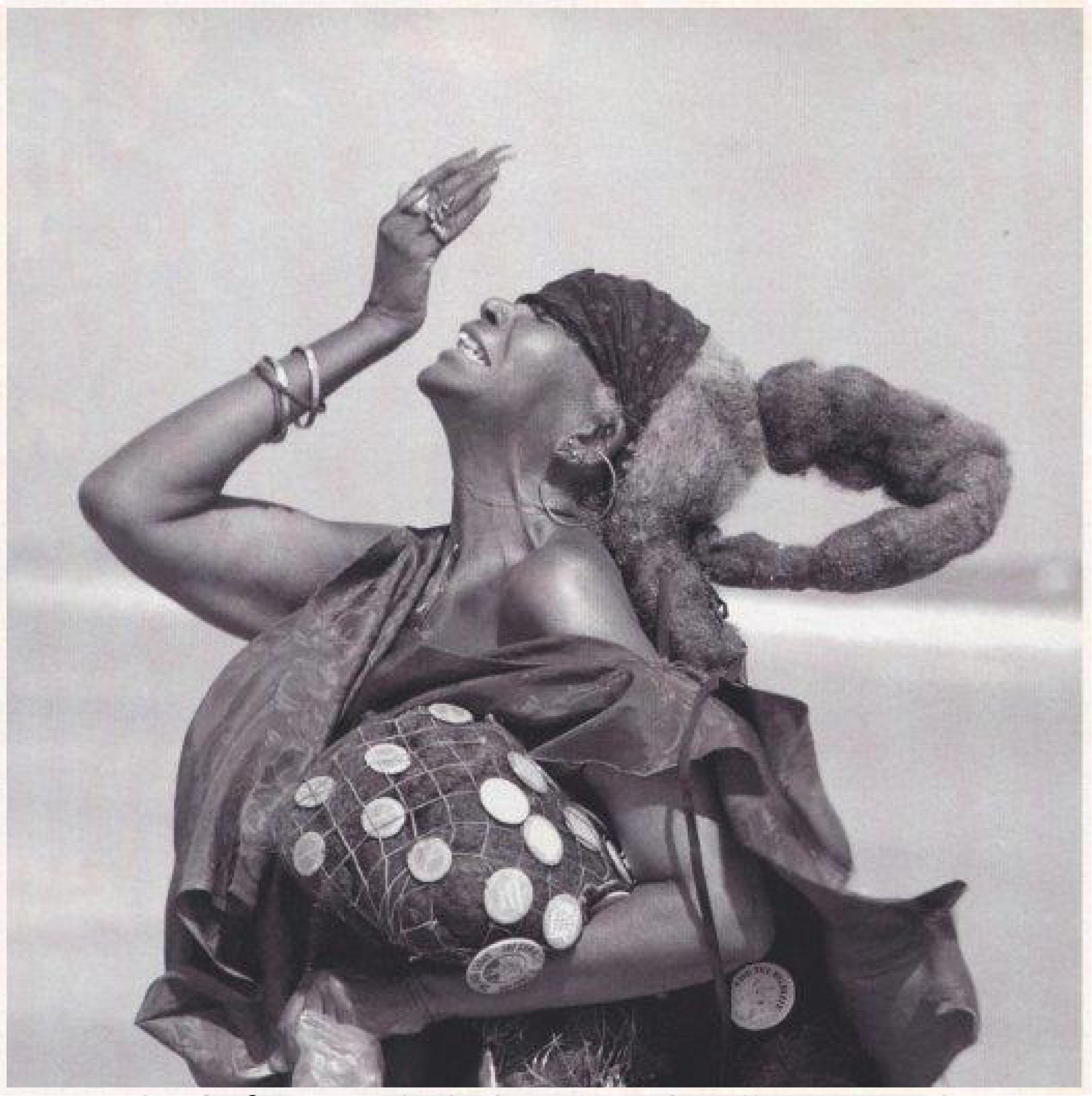

This belief system is only part of the legend MaVynee left behind. With a seven-foot six-inch dreadlock, and long, wild nails, MaVynee Osun is best remembered as the Beach Lady.

“I think people started calling her that as a derisive thing,” Frances says. “But MaVynee was born in that briar patch. She just embraced it and started calling herself by the third person.”

With her searing intellect, deep spirituality and 7 foot dread lock, The Beach Lady was a free spirit who fought for historical and ecological preservation of American Beach. Photo by Eric Breitenbach, courtesy of American Beach Museum

MaVynee returned to American Beach in 1975. She slept on the beach in her own chaise, bathed in the ocean, and gave tours of the area while fighting for the historical and ecological preservation of American Beach.

As noted inside the American Beach Museum, the high dune system called NaNa was preserved as a national park due to MaVynee’s environmental activism. In the face of major development, MaVynee fought to preserve the Franklintown cemetery.

Alexander, who calls MaVynee her spiritual mother, says, “She was this person that knew how to market. She was an excellent writer. She wrote to every newspaper, every periodical.”

Her writings would then reach journalists who would travel from as far as Detroit or California to American Beach where they would meet the Beach Lady in full regalia.

“She would have some theatrics,” Alexander says. “She could quote something, she could sing something, she had a brain, talked about the environment. She was a scientist. She was an engineer.”

And in this way MaVynee the Beach Lady helped preserve American Beach. In fact, Dr. Cole, MaVynee’s sister, says, “There’s been so much written about my sister. And for me the most moving and special chronicling is in Russ Rymer’s book, American Beach.”

“MaVynee was free,” Frances says. “I feel like if I had just wandered onto American Beach, as many people did, and saw her standing on the corner of Lewis and Greg, and sat down and talked to her for an afternoon, [I’d] never forget that.”

MaVynee Osun, “the Beach Lady,” 2005. Photo courtesy of American Beach Museum

Anyone who met MaVynee remains transformed by her enigmatic presence. But who was she? That answer can only come from her sister.

“She was absolutely brilliant,” Dr. Cole says. “When individuals saw her, in the fullness of her six feet of height, and the drama of her hair, and the colorfulness of artistry in the way she dressed, I’m not sure folk were always remembering they were in the presence of a brilliant Black woman.”

MaVynee died on September 5, 2005 at 5:01 a.m., just as she had predicted, Alexander says: “She said, ‘One day it shall be me and 5.’”

But MaVynee is absent only in body. Her spirit is alive and well and permeates every inch of the American Beach Museum. Her dreadlock hangs enshrined from the ceiling, imposed upon a hologram-like image in glass. A video allows visitors to go on one of MaVynee’s tours of American Beach.

Her aged and gravel-rough voice booms, “The richness that is American Beach is its history.”

The history of American Beach is what brought me — and 350 others — together inside a community gallery to gaze upon the photographs, mixed-media artworks, and the newly created T-shirts of artists Malcolm Jackson, Dustin Harewood, and Jordan Walter. In their work, what confronts the gaze of the aesthete is Black people, Black life, and Black culture barely surviving in an area they created and dominated.

“It’s a sign of the times,” Annette Myers says.

“That house is one house,” Marsha Dean Phelts says. “But it’s gon’ be timber on American Beach for African-American people. Timber. Not the fall of the trees, but the fall of the houses.”

In Malcolm Jackson’s hauntingly beautiful black-and-white photographs, the pristine coastline sits in stark juxtaposition with homes falling apart, some with tarps still on their roofs after hurricanes in 2016 and 2017 pummeled the coastline.

“With this work being a documentation of the current state of American Beach, I want people to have a bit more appreciation for what we do have while we have [it],” Jackson says. “I want them to understand this is important not just for Florida history, Jacksonville history, but American history.”

Mixed-media artist Dustin Harewood was inspired by Jackson’s photographs to present “The Black Beach” exhibition. Originally from Barbados, one of his works in the show, “Encroachment,” tackles the disappearing ecosystems fostered by coral reefs, and serves as a metaphor for what is happening at American Beach.

“When I started down American Beach and noticed we had the Omni coming from one side, the Ritz-Carlton coming from the other side, and developers coming in, I thought this was a very interesting parallel to draw between this idea of you have this beautiful thing, and then, if you look at those paintings, you’ll see I’m whiting them out, canceling a lot of it out, and leaving just little bits of the color.”

Many of the houses on American Beach have fallen into disrepair from hurricanes and lack of investment. As American Beach homeowner Martha Dean Phelts puts it “some families are selling their homes, not because they want to, but because they may have to.” Photo by Malcolm Jackson

But simply remembering the heyday of American Beach or lamenting its present state is not enough to save it. Peri Frances — along with friends, concerned citizens, and lovers of American Beach — have formed a collective called American Beach Afrotopia. Their goal is to foster a cultural renaissance and bring people back to American Beach.

“One of our main focuses was on campouts,” Frances says. “We would camp out in nature on American Beach as a way to inhabit that space, feel that energy, but to also pay homage to the Beach Lady.”

Frances’ campouts were first put on hold after the local government in Nassau County capitulated to wealthy homeowners who complained about “frat-house”-like campouts in Peter’s Point, not American Beach. The future of campouts is still unknown as Florida in general, and Nassau County specifically, slowly reopens amid the COVID-19 pandemic. While beaches are open, social distancing guidelines are still in effect.

Despite the setbacks, Frances is not defeated.

“The way you save American Beach is to come to American Beach,” Frances says. “How you perpetuate it as a historical space for free people, free Black people, is bring your free Black self: bring your family reunion, bring your church group, bring your sister circle, bring your book club, bring your yoga class. Bring your school group. Come! Come! Come! Come!”

Jordan Walter agrees. He believes the key is to bridge the gap between past and present: “If you support these areas by visiting and supporting that community, it will carry on. We’re quick to give our money and our time to other people, but we don’t give it to ourselves.”

For Dr. Cole, Annette Myers, and Marsha Dean Phelts, the way forward in American Beach is a much more committed approach: homeownership.

Dr. Cole says, “If you’re doing what my husband and I are doing, and that is taking all of our little savings and building a home on American Beach, which will be the last home in which I will live on Earth, I think that says what you think the future is.”

Annette Myers, who authored the book The Shrinking Sands of an African-American Beach agrees and calls for “African Americans who can afford to build here” to invest in single-family homes.

But Marsha Dean Phelts, who has authored three books on American Beach, including a cookbook and a book of homes, says she believes the lights are already out on American Beach. While she is a homeowner, and believes that is a way to preserve American Beach, she recognizes some families are selling their homes, not because they want to, but because they may have to.

“[They’re] selling because there may be a need, or a cause to leave, but in terms of dollars … like hell. Girl, no …. We wouldn’t have been here if money was the thing that would get us out of here.”

Photo by Peri Frances

For now, American Beach still exists, with or without hordes of tourists flocking to its shores to experience its magic. It exists as a testament to Black excellence, as an illustration of Black collectivism, and a representation of the power of cooperative economics. Eighty-five years after it was founded, American Beach still is, thanks to the work of MaVynee, Carol J. Alexander and the American Beach Museum, Annette Myers, Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, Marsha Dean Phelts, Peri Frances, Dustin Harewood, Malcolm Jackson, Jordan Walter, and so many more who still speak its name.

The future of American Beach, its next 85 years, is contingent upon us, people like me who follow the whispers of history into places and spaces that are both historic and sacred.

“American Beach is this treasure that is beginning to be uncovered,” Alexander says. “If we don’t preserve, and build more history, and put it in people’s faces, it’ll lose.”

Dr. Cole is adamant that American Beach is neither losing nor failing. During our interview, she was adamant the headline of this story should not be “The Rise and Fall of American Beach.”

Thus, this piece is but another whisper to the future of American Beach. My obedience to follow the story to the shores of its origins, speak to its caretakers, and share these experiences with my 5-year-old son (who was present for every interview), is only part of what is needed to ensure the future for a place so deeply rooted in the past. Its future depends on us.

Nikesha Elise Williams is a two-time Emmy award winning news producer and award winning author of four novels. She was born and raised in Chicago, Illinois, and attended The Florida State University where she graduated with a B.S. in Communication: Mass Media Studies and Honors English Creative Writing. Nikesha’s debut novel, Four Women, was awarded the 2018 Florida Authors and Publishers Association President’s Award in the category of Adult Contemporary/Literary Fiction. Four Women, was also recognized by the National Association of Black Journalists as an Outstanding Literary Work. Nikesha is a full time writer and writing coach and has freelanced for several publications. Her fifth novel, Beyond Bourbon Street, centering on the fifteenth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina will be released this August from NEW Reads Publications. You can find her online at newwrites.com, Facebook.com/NikeshaElise or @Nikesha_Elise on Twitter and Instagram.