What if we told you that in 1921 a battle raged on American soil in which a million rounds were fired, bombs were dropped, and 10,000 Appalachians fought for their livelihoods? In this excerpt from his new novel, Rednecks, Taylor Brown introduces us to some gritty characters, both real and imagined, who waged the largest labor uprising in American history. Union miners versus King Coal. Can you smell the smoke?

From the Upcoming Novel by Taylor Brown

March 17, 2024

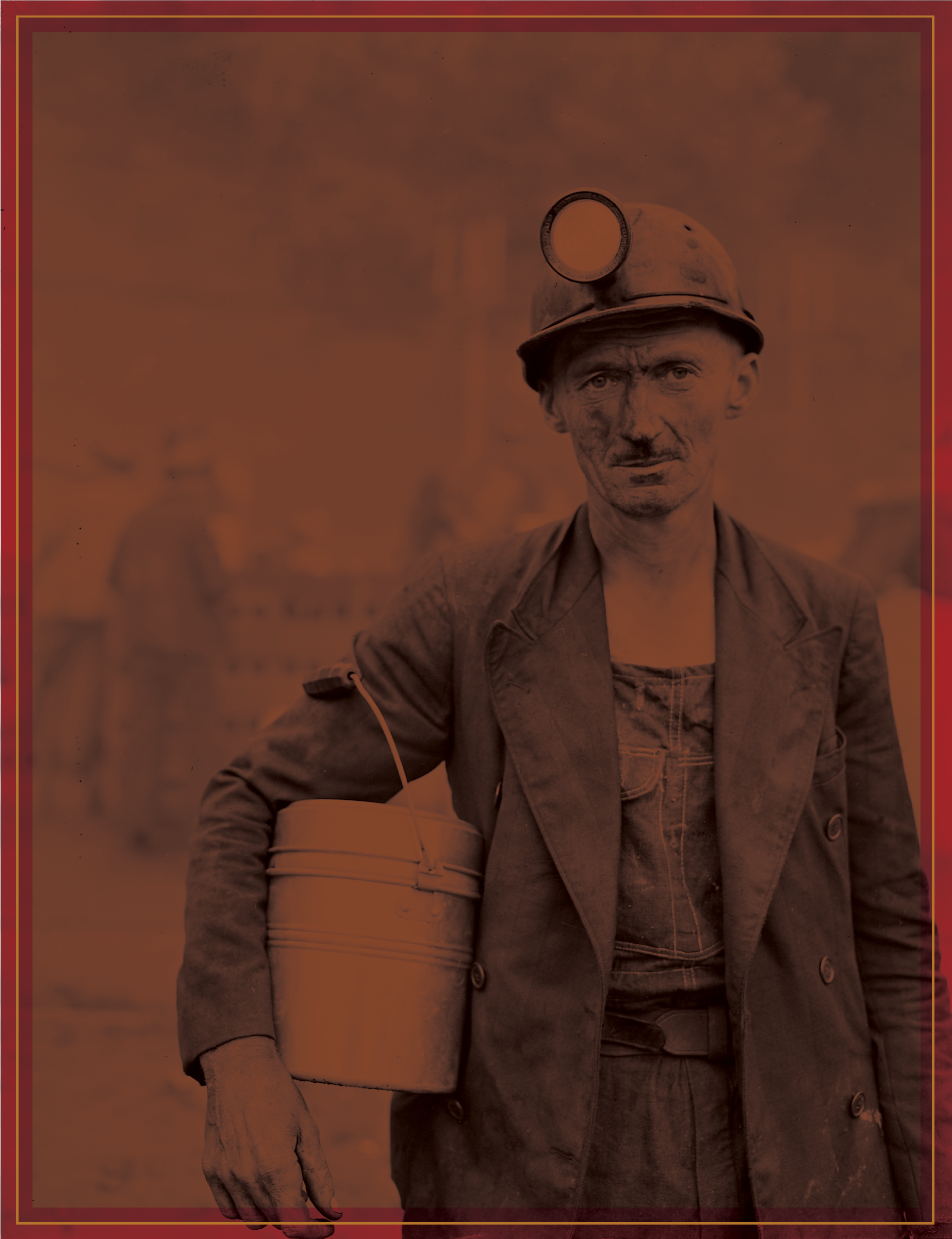

THEY WORK BENEATH the pale flames of carbide headlamps. Some swing picks into the face, hewing the coal straight from the seam, while others shovel the black rubble into iron carts. All crouch like boxers in this shoulder-high chamber, which they call a room. They work dark to dark in this mine, descending before daylight touches the deep, coal-camp hollers where they live and surfacing ten hours later, soot-faced as chimney sweeps, the last glow of dusk to greet them.

The mine cars are drawn to the surface by mules born underground, animals who only know darkness, like some cave species, pulling their trains of coal through swinging trapdoors attended by ten-year-old boys who curse and sweet-talk them in turn. Boys they kick into the wall when they like. All breathe a black dust, explosive, which swirls through the cramped, yellowy light. The pickers and shovelers work with red bandannas knotted over their faces, the cotton black-fogged over their noses and mouths.

Perhaps it’s an inadvertent spark from a miner’s pick, striking an unseen shard of flint. Perhaps a pocket of methane has just been exhaled from the strata, freed after eons. The mountain erupts. A train of fire bores through the tunnels and shafts and rooms. Men are burned alive, boys buried underground. A great plume of ash blows from the mouth of the mine and rolls skyward, seen for miles.

The morning papers will read 21 KILLED IN MINE BLAST. The country will hardly register the news. Such headlines are frequent, far removed from the reading public, like earthquakes or eruptions on far sides of the world.

Outside the drift mouth, two miners lie on their bellies, heaving, their hands atop their heads. They look at each other. Red-eyed, dizzied, ears a-whine. The world blows around them, dust and smoke and red meteors of coal. Everything clad in a pale of ash, thick and wooly. Tonight the coal camp will wail with death.

One raises his head. “Told you she’d blow, ain’t I? This wouldn’t never happen at no Union mine. We’d have them vent shafts we asked for.”

The other miner looks over his shoulder, eyes wild, as if the Devil might be standing behind them, marking their words. He hisses through his teeth: “Hush with that talk, man. You’re like to get us kilt.”

OC MOO WAS UP at the coal camp above town, checking on an elderly patient of his, when the Baldwins came rattling up the road in a pair of tin lizzies, their rifles and shotguns prickling from the windows like hackles and spines. The doctor touched the small, three-barred Maronite cross at his throat.

“Al’aama,” he whispered. Blindness. The same curse he used to hear his father utter in the back of their barn, swearing over a busted plow harness or olive rake on their farm in Mount Lebanon. Doctor Domit Muhanna hadn’t seen his father since he set sail for America thirty years ago, at the age of fourteen, landing at the Port of New Orleans and traveling upriver on a Mississippi riverboat full of Kaintucks with long knives and short tempers — boatmen traveling home after blowing their pay in the taverns and flophouses of the French Quarter. Muhanna was headed for the University of Kentucky — a brilliant student, his family’s great hope to carve a life for future generations in America.

He feared he wouldn’t survive the Kaintucks and their beloved bowie knives until one of them slashed another over a galley card game and he managed to sew up the wound with catgut from one of their fiddles — suturing a skill he’d learned as a goatherd, not in any clinic, but the boatmen were well-pleased, slapping his back and pouring rotgut whiskey down his throat.

“Ought to bring ye to ever poker match so the hangman don’t string us up!”

Muhanna graduated medical school and opened a practice in the feud-hot borderlands of Kentucky and West Virginia, earning a high place in the esteem of the community despite his tobacco skin. A man willing to mount his great white horse at any hour and barrel through the country darkness to attend to childbirths and hemorrhages and hysterias on both sides of the Tug Fork River, fevers and gunshot wounds and the black-bloody lungs that came with years in the mines, sucking coal dust underground. Some people said he’d saved more Hatfields and McCoys than Jesus Christ — others said that wasn’t but poorly few.

Now his patient, Miss Beulah, patted his arm. She didn’t know Arabic, but she could tell a swear when she heard one. “Don’t cuss ’em just yet, Doctor Moo.” She cut her eyes at the Baldwins getting out of their cars. “Best wait till the thugs can hear you do it.”

Miss Beulah had been born in Georgia sometime around 1850. She didn’t know her exact age, but she’d got her blood the same year the War Between the States blew the country wide open and a whole bunch of men and women and children with it. People thought the Mason and Dixon line was some kind of sharp divide, like it was made with a captain-man’s saber, but there wasn’t a thing sharp and clean about it. It was more like somebody had blown them free with dynamite. Sherman had come through and burned their cabins to the ground alongside the big house and the gin house and the cotton cribs, and soon enough it was the whitecaps and Ku Kluxers night-riding through the land on their white-hooded horses, slinging their ropes and fire like hell on parade.

She and her husband came up to West Virginny in 1880 for him to work in the coal mines opening on the backs of the railroads carved through these mountains. Hellish work down there in the mines and these shabby company towns with their paper-thin houses and tin-scrip money and black dust that got everywhere, all the time — up your nostrils and between your toes. Every man jack of the miners, no matter his skin, came home looking dark as those ancestors of hers when they first stepped off the slaver’s boat. Her husband had died of the miner’s asthma in 1900 and she spent her days now on this little porch of her grandboy’s cabin doing sitting-work, darning socks and quilting blankets, her feet swole up like pink-brown piglets beneath her rocker. The dropsy, what it was. The nice Doctor Moo came to give them a draining once every week.

Her eyes had been clouding these last few years, but she knew Baldwins when she saw them. They weren’t but thugs, petting their oil-slick rifles like skinny little girls. Her grandboy Big Frank had gone to the Great War himself carrying such a gun. People said it was safer to serve Uncle Sam over there than King Coal back home. A statistical fact, that. Now she leaned and rang the spittoon beside her, gripping her rocker’s arms hard enough the old chair crackled beneath her.

“Strength, Jesus,” she said. “Strength for this ole tongue.”

The gun thugs came strutting stiff-legged up to her house first. She figured they would. Their fine town shoes squelching in the muck. Above them, above the sooty roofs of the coal cabins and the steep dark sides of the holler, so steep the trees grew nearly lying down, big clouds of mist held sway. Rain soon, she thought. The head thug snapped his fingers like she was a dog. She knew who it was. One of the three Felts brothers who lawed for P. J. Smith who ran the Stone Mountain Mine that owned the houses and the store and the church and thought it owned them.

“Beulah Hugham,” he said, reading from a list in his hand. “That you?”

“Miss Beulah to you. I seen that mug of your’n up here not a month back.” “I’m Special Agent Albert Felts of the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency. The lessee of this house, Mr. Frank Hugham, has been terminated from his employ in consequence of joining the United Mine Workers of America labor organization. We’re here to carry out the eviction.”

Behind him, agents were already going to other houses, knocking on doors, using skeleton keys if no one was home. They were coming out with chairs and pictures and folded quilts, stacking them on the side of the street.

“Hell you is,” said Miss Beulah.

“Excuse me?”

“Special agent, hell. You ain’t got a lick of authority outside that gun on your belt. I ain’t coming off this porch without some real law making me.”

Felts took a step closer. “We’ll see about that.”

Doc Moo held up his hand. “Now hold on here, Agent Felts. Mr. Frank Hugham has already vacated. He moved to the Union camp up on Lick Creek last month. But Miss Beulah here is in no condition to be living up there in one of those canvas tents, all but out of doors. I already cleared this exception with Mr. Smith, the mine superintendent.”

Since the start of the year, many of the county’s miners had joined the United Mine Workers of America labor union. The coal companies had responded with mass firings and evictions. For weeks, the ousted families had been living in tents outside town. Men, women, children, pets, livestock. A few refused to leave home, too old, sick, or stubborn to budge.

The chubby-cheeked agent next to Felts shook his head. “Smells like bull to me, Boss.”

Felts looked around, sniffed. “What doesn’t?” Then to Doc Moo: “There will be no more exceptions starting today, Doctor, by order of the Baldwin-Felts.”

Felts jerked his head to the other men, who palmed their belted pistols and started for the porch. Doctor Muhanna stepped in front of them, his heart firing rapidly in his chest. “This woman is a patient of mine, and this eviction is illegal. I want to see a court order.”

In a flash, the blue-black gleam of a pistol in Felts’s hand. “Here you go, Doc. See it here? Now, if you want a special dispensation for the old lady, you can ride your tan ass on up to the mine office and get yourself one. Till then, you stay out of our way lest you want to see how well you can stitch up holes in your own belly.”

Moo gritted his teeth and knelt down beside the old woman. “I’ll be back as quick as I can, Miss B.”

Miss Beulah patted his arm and leaned to his ear, her voice hot in his ear.

“Nothing but thugs. Got-damned thugs, the lot of them. Don’t strain nothing for them.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

Doc Moo was halfway to the mine office, hiking the rough road in his riding boots, when he heard shrieks and curses behind him. He looked back in time to see the agents lifting Miss Beulah from her porch in her rocking chair, hoisting her high on their shoulders like a queen or lady of renown, then setting her down in the middle of the muddy street, where she cursed and swung her gnarled fists at them.

“Allah Yakhidkoun,” he hissed.

God take your souls.

MILIN’ SID HATFIELD, KIN to Devil Anse, stood on the plank porch of the hardware store, his palms set casual over the curved handles of his double-action revolvers. He was the tenth child of twelve. One of nine who survived. The badge over his heart read MATEWAN POLICE, with the number “1” stamped between an eagle’s wings.

Chief.

His head was shaved high over his ears, his hair grown spiky from the crown of his skull. His tie was wide and flat and short, decorated with paisleys. People called him “Smilin’ Sid” on account of the gold caps on his teeth, which flashed whenever he smiled, which was all the time. A gold metal smile, loved and feared. Folks said he was cut from the same stump as old Devil Anse himself, patriarch of the Hatfield clan, who lived in a bulletproof log fort not ten miles from Matewan, his beard grown long and gray as a wizard’s.

Sid cocked his head. Thirteen men stood in the street before him. Men from the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency. Mine guards. Gun thugs. Hard-faced men in city-cut suits, who thought they were the law here in the Tug Valley, where the railroads had come boring through the mountains at the turn of the century and coal became king.

Here, four of five towns were coal camps, company towns that smoked from the hillsides, and miners worked ten hours per day, six and one-half days per week, paid forty cents for each long ton of coal they blew, picked, and shoveled out of the sunless dark of the mines, where collapse and explosion and sickness lurked. A land where any attempt to organize, to join a union for better pay or safer conditions, was met with these men in the street.

The Baldwin-Felts, hired guns of King Coal.

Some of them cradled self-loading rifles disguised in butcher paper, like cruel bouquets. Others held their gun-hands inside their coats like upstart Napoleons, thumbing the hammers of their pistols. They pushed their bellies with pride against their belts.

Sid smiled back at them, showing them the raw blade of his teeth.

They’d built themselves an ironclad automobile for use in the silver mines out west, using it to machine-gun striking miners as they huddled in trenches dug beneath the duckboard floors of their canvas tents. The Death Special, they called it. A girl was shot in the face, a boy shot nine times in one leg. For West Virginia, they’d built the Bull Moose Special, an armored locomotive that steamed past a strikers’ tent colony up on Paint Creek in ’13 with machine guns ablaze, blasting the brains of a well-loved miner across the walls of his frame house.

Now they’d come to Matewan.

Mingo County, West Virginia.

Sid’s town.

That morning, they’d gone up to the coal camp above town and thrown out the families of every miner who’d joined the Union. While the men were at work underground, they’d forced out the wives and children at gunpoint, piled their belongings in the road, and barred the doors behind them. Quilts and kettles and hobbyhorses were hurled out into the rain, cane chairs and hanging mirrors and old war uniforms — anything the company didn’t own.

Now they’d come for Sid.

Days back, their leader, Albert Felts, had offered him one thousand dollars to mount machine guns on the town rooftops — enough cash-money to buy three Ford motorcars fresh off the lot. Sid had smiled at Felts and told him what he could do with his machine guns, where he ought to insert them. The man didn’t seem to understand that you could buy a whole valley, but not the people who lived in it.

Now Felts stepped forward from his bunch, holding out a writ. “We got us a warrant here for your arrest, Hatfield. You’re gonna have to come back to Bluefield on the train with us.”

Sid kept smiling. “Say I am, Albert?”

Past the man, not one hundred yards from where they stood, ran the heavy green water of the Tug Fork River, which divided West Virginia from Kentucky. In this borderland, Sid’s ancestors had warred with the McCoy clan for thirty years before his birth. Hatfields had splashed back and forth across the Tug Fork in midnight posses and raiding parties, revolvers thumping against their thighs, shotguns slung across their backs on strings and ropes. Men of his blood had tied McCoys to pawpaw bushes and shot them to pieces. They’d set fire to McCoy cabins in dead of winter so that McCoy children went barefoot in the snow.

Sid had come up on a tenant farm just across the river. As a teen, he’d wielded a pickax and blasting powder in the mines, back-bent in those squarish caverns of rock eons beneath the earth where blackdamp could choke a man to death and firedamp blow him to kingdom come. Friends of his had been killed in roof falls and blasting accidents; he’d seen boys not ten years from their mamas’ bellies with their fingers sheared off in coal conveyors — one squashed dead beneath the wheels of a mine car. A sight you never unsaw.

His hands were black-seamed from the mines, cuts and blisters healed with coal dust under the skin, as if tattooed. He’d worked as a smithy’s striker, too, swinging a sledgehammer onto an anvil again and again, pounding shapes from that glowing iron, dousing red-hot horseshoes and plow blades in bubbling cauldrons of quench water. Policing was the first trade in which his face wasn’t blacked with dirt or coal or soot, only his eyes and teeth to show.

“That’s right,” said Felts, cocking his head, his dozen thugs spread wide-legged behind him. “We’re taking you back to Bluefield in cuffs.”

A warmth at Sid’s hips. His shooting irons turning hot in their holsters, same as always before a fracas, as if they recalled the hell in which they’d been born. The red iron, liquid, hammered into the die. He looked from man to man of the Baldwin bunch. They were beginning to shift their weight from foot to foot before him, twitching their noses and tapping their fingers, wondering why he was still smiling.

Sid had dug the black veins of West Virginia coal that made the companies rich that hired these men. Money that could buy mansions on the shores of cold clear lakes and twelve-cylinder Italian automobiles and murder in muddy streets behind the gleaming badges of private detective agencies. Coal money, God-strong in Mingo County. Sid smiled because he was risen from the mud of this place, born to meet such men in the street.

The mayor, standing beside him, squinted at the warrant the Baldwin-Felts had produced. A misty rain was falling now, slanted and feathery, tickling the shoulders of the agents’ suits. Tiny bright pearls in the wool. Sid knew these men had warred for their country in trenched hells of mud, killing Krauts with machine guns and hand grenades and trench knives. He also knew they were aliens in this place, in these jagged dark shadows between the hills of his birth. He stepped slightly back into the door frame, feeling the darkness drip down his face.

He could be happy-go-lucky Sid, devil-may-care Sid, the Sid who didn’t but shoot pool and play poker and run around with the other young men, chasing bucks and gobblers and big brownie bass. But these Baldwins, they just wouldn’t learn. They had to come here and throw his people out their homes without the due process of law. They had to hurl their family heirlooms and hard-bought belongings in the muck like a bunch of trash.

They had to put an old woman out in the rain.

There was the law of the courts, Sid knew, and the law that was older, deeper, which even the littlest trapper boy in the mines knew in his born heart. Which even that boy’s greatest granddaddies had known ten generations back, in whatever highland or desert or forest raised them. There were some people these days who’d chosen to forget that older law, but only because they could. Because somebody had done away with their Baldwins for them, put them in prison cells or pinewood overcoats.

Not a month ago, this same bunch had been arrested for this same crime. Albert Felts had leered at the arresting deputy over a mine office desk covered in guns of every caliber and description. Large-frame revolvers and sleek automatics, bull-nosed shotguns and high-powered rifles with telescopic sights — the latest in handheld firepower. “Know this, I’ll break the unions of the Tug Valley if I have to send one hundred more men to hell.”

Here he was again, still cock-lording about, no matter his late arrest. A man irreformable, it seemed. The Baldwins had the coal operators on their side, which meant the judges, the politicians, and half the high sheriffs of the state. But Sid knew that wasn’t the root of the problem, the real reason they kept coming back. The reason they could. It wasn’t something they had on their side. It was something they lacked.

Fear.

They didn’t know this county had been called Bloody Mingo long before the companies came to unbury the coal kept deep in the guts of the hills and send it forth in mile-long trains of dark rubble to light the boilers of ships and trains, steel factories and power plants. A land of fracture and feud, where men of the same family fought on different sides of uncivil wars and bands of marauders roved the hills since the days of scrape-fires and cap-shooters and a man had to be willing to kill and die to earn any single inch of respect.

They didn’t know where they were. In whose valley they walked.

It wasn’t a thing that could be told.

Someone had to show them.

Sid never took the wearing of the badge lightly. It made the whole town his family, his kin. Here in the Tug, lawing meant swinging fists and wrestling down drunks, raising ax handles and sometimes a gun. It meant sacrifice. A lot of people thought dying for something was the biggest sacrifice of all. Like Christ. But Sid knew there was something more than that. Something he’d learned from Devil Anse himself. They all had. A man didn’t just have to be willing to die for his kin, but to burn in Hell.

To damn himself.

In the distance, the whistle of the 5:15 train, carrying the promise of arrest warrants for the Baldwins from the county seat. Mayor Cabell looked up from the writ. “You got to be shitting me, Felts. This arrest warrant is bogus.”

Sid knew it would be. He leaned back farther into the shadow of the hardware store, feeling the darkness paint his cheeks, run down his neck. The butts of his pistols glowed like skillet handles beneath his palms.

“You’d better wrote that warr’nt on a ginger snap,” said a listening miner, spitting in the road. “So ye could eat it.”

The detectives in the street smiled, hard-faced, like it was all a joke. Then Albert Felts reached into his coat — or so Sid would tell the jury later. Albert Felts, who’d boasted he would break the unions of West Virginia if he had to send a hundred more men to Hell.

He would go first.

Sid’s pistols leapt from his belt. He shot Albert Felts in the head, a halo of spray. The other agents dropped to shooting positions, drawing their guns to return fire, but the rifles of hidden miners cracked from trees and bushes and windows like a dam breaking. Like Sid knew they would. The Baldwins were sent tumbling and screaming, dying in the street. They turned tail and fled, and Sid stepped down from the porch and walked after them, his pistols barking again and again at the ends of his hands, like the barking mouths of dogs. ◊

Pre-Order Your Copy of ‘Rednecks’ Here

From “Rednecks” by Taylor Brown. Copyright © 2024 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Taylor Brown is the author of the short story collection In the Season of Blood & Gold, as well as the novels Fallen Land (2016), The River of Kings (2017), Gods of Howl Mountain (2018), Pride of Eden (2020), and Wingwalkers (2022). You can find his work in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Garden & Gun, and many other publications. He’s a recipient of the Montana Prize in Fiction, a three-time finalist for the Southern Book Prize, and was named the 2021 Georgia Author of the Year for Literary Fiction. He lives in Savannah and serves as editor-in-chief of BikeBound.com, a custom motorcycle publication.