Tennessee-born Joseph Shipp turned up at The Bitter Southerner two years ago with an incredible archive — thousands of photos, shot across many decades, in a single Southern community. This is the story of how those photographs became a book — and what they might teach us about our region.

Words by Chuck Reece | Photographs by Tamara Reynolds and Joe Hardy Shipp

It started two years ago with a phone call to our co-founder Kyle Tibbs Jones from Jason Travis, who has repeatedly contributed photographs and films to The Bitter Southerner.

J-Trav, as folks in Atlanta called him before he moved out to Los Angeles, had a friend whose husband, he said, had discovered a treasure trove of old photographs he thought we should see.

We had no idea that phone call would lead us to publish our first hardcover book, A Community in Black & White: A Most Unusual Photo Album of One Southern Community. When we first met Joseph Shipp, who owned the archive, and his family, we found a trove of beautiful stories. But more importantly, we discovered a remarkable archive of 16,000 negatives — photographs shot in the mid 20th century in one specific Southern community: Hickman County, Tennessee.

Scenes from Centerville, Tennessee. Photos: Joseph Hardy Shipp

Joseph Shipp was the grandson of Joe Hardy Shipp, who in 1946 gave up farming to open a photo studio — Shipp Studio — in downtown Centerville, the Hickman County seat, about 50 miles southwest of Nashville. For decades, Joe Shipp and then his son, Ronnie (Joseph’s father), shot pictures of seemingly everything that happened in Hickman County — school pictures, weddings, funerals, car accidents, even jailbreaks.

But there was something odd in these photographs. In that period of the 20th century, Jim Crow was the law of the land in the South. Black people and white people co-existed in small communities like Centerville, but their lives were almost entirely separate. And in those days, black businesses served black clienteles. The same was true among the white folks. But about 10 percent of Joe Hardy Shipp’s photographs — a percentage roughly equal to the black population of Hickman County at the time — were of the schools, weddings, and social gatherings of African Americans.

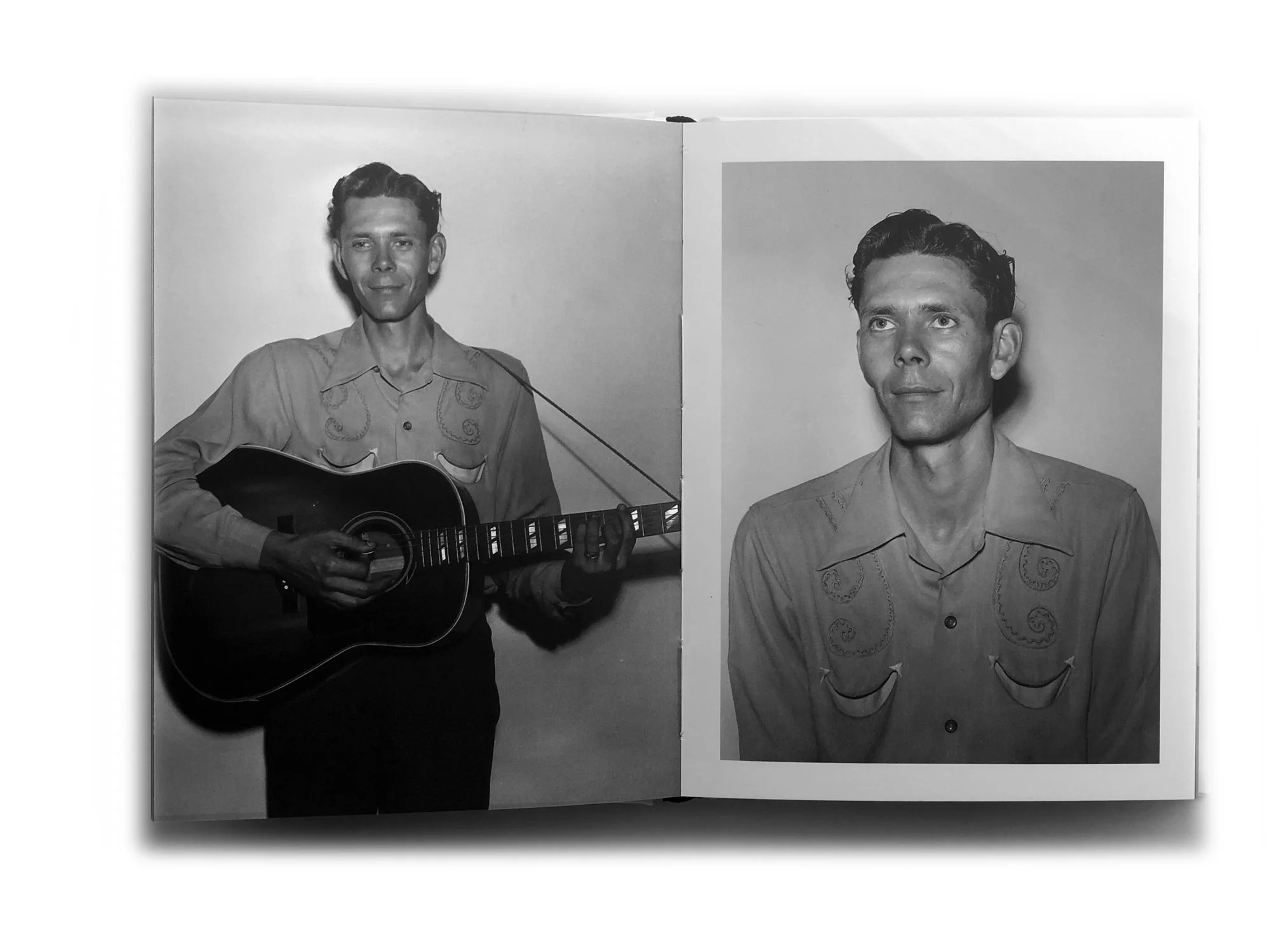

Pictured above: joe shipp

Joe Hardy Shipp, it seemed to us, was a different kind of rural Southerner, one who plied his services to everyone in the county, regardless of race.

We had questions. Were the Shipp family’s photographs unique in the way they portrayed Southerners on both sides of the color line? Were there other collections like this?

We consulted Richard McCabe, the curator of photography at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans. You could almost hear the reluctance in his voice when we explained we had an archive of 16,000 photos shot in the same Tennessee county, across many decades. Photography curators, it seems, are primary targets for almost anyone who finds an unexpected trove of old photos, which is why McCabe pronounced himself “really skeptical of these old things.”

Then, from a small website Joseph Shipp had built, we showed him a sampling of the photographs. Across the telephone line, we would hear McCabe’s skepticism morph into excitement.

“You very rarely see, in these archival collections like this, a mix of black folks and white folks,” he said. “These pictures are beautiful.”

We reached two conclusions: First, the Shipp collection was uncommon. Second, Joe Hardy Shipp was a profoundly talented photographer.

It wasn’t long until we found ourselves sitting around the table in Betty Breece’s kitchen outside Centerville. Breece, 72, is Joe’s daughter, Ronnie’s sister, and Joseph’s aunt. Joseph’s mom, Floy, was there, as was Joseph’s uncle, Joe Thomas Shipp, now 75, along with several other members of the extended family.

Joe Thomas Shipp has worked in the timber business all his life, and he spoke to us in the direct manner of working folks. We asked him if anyone in Hickman County had thought his father’s willingness to work for black and white clients alike was unusual.

“To some people, it was,” Joe Thomas replied. “But we weren’t raised racist at all. Daddy. He’d sit down at a table with black folks and eat dinner just like I would. I didn’t think nothing about it. Grew up that way.”

It was a straightforward explanation for the diversity in Joe Hardy Shipp’s photographs: The man saw no reason not to photograph the black people he shared Hickman County with.

Gathered around the table, from left to right, Joe Thomas Shipp, Betty Breece, Shirley Shipp, Joseph Shipp, and Floy Hildabrand. [Photos by Tamara Reynolds]

As the family chattered and told stories about the two missing faces in the room — the late Joe Hardy and his son, Ronnie, who passed away in 2003 from cancer — the family dragged out photo albums and talked about the memories arising from the images. Floy told a story about a time when her husband Ronnie was invited to photograph a church service in one of Centerville’s largest black congregations.

Pictured above: Ronnie shipp

“I think it was maybe a big anniversary for the church or something,” Floy said. “Ronnie was always one of these people that liked to stay low-key. He didn't want the photographer to be the main person everybody looked at all the time. David [an assistant at Shipp Studio] went with him to help him with the cameras. They got up there, and the congregation all was there. Ronnie said, ‘We were just gonna slip in the back door and sit on the back seat until they got through with everything that was going on. But when I opened that door, and the minister was up there talking, he stopped and said, “‘Mr. Shipp is here. Please come up here to the front of the pews and have a seat. We have it waiting on you.’”

“Those types of things never bothered Ronnie or our daddy or any of us,” Betty said. ”It didn't bother any of us, and everybody respected Daddy and respected Ronnie. They respected other folks. When you respect somebody, you're gonna get respect back. Some people, they're your best friend when they're making your picture, and then you go out, and you meet them on the streets, and you might not speak to them. That was not Ronnie or Joe. They knew you regardless of the situation. They always was your friend.”

Or as Joseph put it, “You can look at these images in a lot of ways, but you can always tell they loved these people. They were these people. They had a deep affection for this community.”

It wasn’t until we already had A Community in Black & White at the printer when I learned that Joseph Shipp had hoped, even before he visited The Bitter Southerner, that these photographs would turn into a book.

“Books are many things,” Joseph told us in a late November conversation. “Books are artifacts. Books are legitimate. Having a book means that someone took the time and money to publish it because they deemed the subject worthy of putting out into the world for others to see. Books are precious. Books are proof. Books are permanent.

“This book personally means I have a meaningful new heirloom to pass along, but one that is also a group celebration of Joe and Ronnie's legacy,” he continued. “One could say that I'm looking to bring honor to my grandfather and dad through this project. Not only honor to their names but the Shipp family as a whole. I'm very proud of my family history. In many ways, this is just one manifestation of that pride. I'm also proud of where I grew up. I hope it brings honor to those things as well.”

No book would exist had Joseph not discovered the archive of negatives in 2014. Even though Floy had closed Shipp Studio after Ronnie’s death in 2003, it was more than a decade until her son realized a treasure trove of negatives were sitting in storage — meticulously preserved and notated by his grandfather.

Joseph was working in California as a graphic designer when he learned about other photographic collections from the early and mid 20th century South, such as the landmark work of Arkansas photographer Mike Disfarmer.

“We had hired a photographer [for a project], and I was telling him about my grandpa, and how I grew up in a photography studio. And then he was like, ‘Oh, it sounds like Mike Disfarmer.” Two weeks later, the photographer sent Joseph a gift, a book collecting Disfarmer’s photos.

“I was just thumbing through it, and the first thing that hit me was like, I need to do this with Joe and my dad's photographs,” Joseph said. “Theirs were as good as this stuff. I called my mom, and I was like, ‘Mom, do you have any of those negatives? Do we have any or prints or whatever?’ And she said, ‘Yeah, we've got all of your granddad's stuff.’”

How many negatives were there? Joseph asked. Floy replied, “There's seven or eight big boxes full of them.”

His mother shipped all those boxes to California, and Joseph began the long process of digitizing 16,000 negatives — a process that remains far from finished. Then, two years ago, he moved home to Tennessee, to Nashville, which is when his book project began in earnest.

It’s a project, Joseph hopes, that can resonate far beyond the boundaries of Hickman County, or even the entire South.

“I see the possible messages this project can deliver, so I hope that comes through and resonate with others,” he said. “I hope it opens up a dialog about the social, racial, political, and economic contrasts in these photos. We are living in such divided times right now in America. I believe it's the role of art to help provide some answers to whatever's going on. Maybe this book only offers more questions, but I believe whatever it brings to the table it is good and meaningful.”