A Reconciliation in Georgia

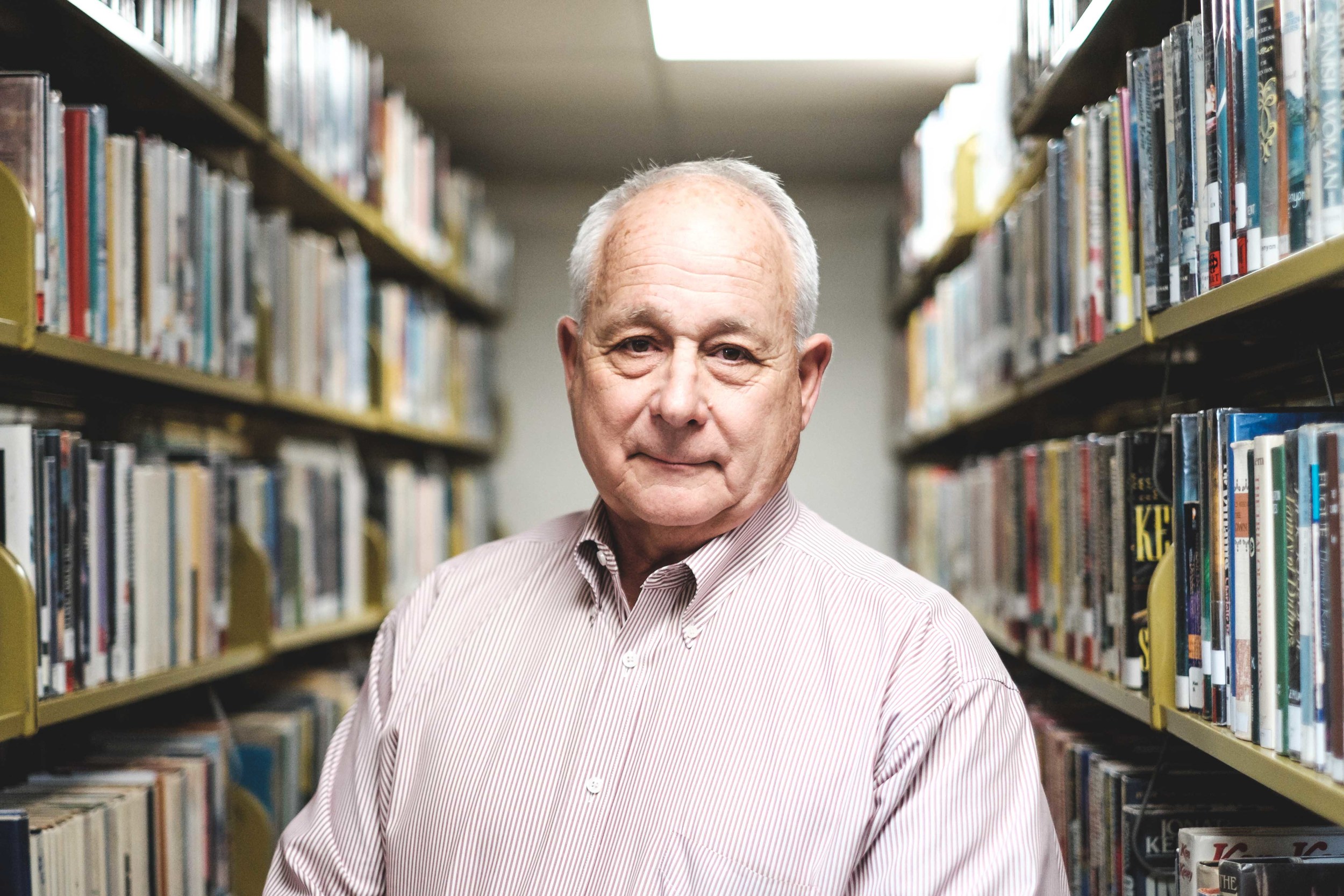

Earlier this year, Atlanta author Jim Auchmutey published “The Class of ’65,” a stunning book about a tortured civil-rights era triangle in Americus, Georgia: black students integrating a public school, one young white man who stood with them, and the white students who abused them all, After the book came out in April, Jim and that now older man, Greg Wittkamper, went back to Americus, where they learned even more about the power of reconciliation — and just how hard it is to achieve.

One summer a few years ago, my wife and I were on vacation at Rocky Mountain National Park when I did something that suggested I probably needed a longer vacation. There we were, surrounded by some of the greatest scenery on the continent, and I felt a twitch to check my voice mail back at the office, at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, where I had worked as a reporter for almost 30 years.

There was a message from a former editor of mine, Ann Morris. She had gotten together with some friends from her hometown of Roanoke, Virginia, and had heard a remarkable story. One of them was married to a man who had just returned to Georgia for a high school class reunion he never dreamed he would be invited to, let alone want to attend. He had been bullied something fierce as a teenager. It had to do with civil rights and a communal farm and the demons of bigotry that had to be exorcised in the South and elsewhere.

“I thought it sounded like your kind of story,” Ann said.

It was. I’ve written about many topics over the years, from religion to politics to food, but I’ve always gravitated toward stories about the intricacies of our race relations. Perhaps it’s because I’m a fifth-generation Georgian who came along during the Civil War centennial years, which coincided with the height of the Civil Rights Movement, both of which unfolded momentously in my hometown of Atlanta. This particular story struck my tuning fork so resolutely that I turned it into a book: “The Class of ’65: A Student, a Divided Town, and the Long Road to Forgiveness.” As that title implies, I found more than demons in this true tale; I found the promise of change and reconciliation – a message of hope that, given recent events in Charleston, South Carolina, we need now more than ever.

Here’s how it came about.

Clarence Jordan, the co-founder and longtime leader of Koinonia, used this small shack as a study. The farm has kept it as a shrine to him called Clarence's Writing Shack. Jordan is best-known for composing the Cotton Patch Gospels, translations of the New Testament into the vernacular language of the South. He was in the shack working on the Gospel of John when he died of a heart attack in the fall of 1969.

When Ann mentioned the name of the communal farm, I recognized it instantly: Koinonia (pronounced COY-na-NEE-ah), a Greek word that means fellowship. Koinonia is known today as the birthplace of Habitat for Humanity, the nonprofit housing ministry, which evolved from an experimental program at the community during the late 1960s, but it had a very different reputation before that. There was a time when Koinonia was one of the most controversial and persecuted religious enclaves in the nation.

It was founded in 1942 near Americus, in southwest Georgia, by two white Baptist ministers and their wives who wanted to live simply, like the early Christians, sharing their resources and welcoming everyone in the spirit of brotherhood. In other words, they ate and lived with black people deep in the heart of the Jim Crow South.

Despite Koinonia’s race-mixing ways, the locals mostly tolerated it for the first few years, as they might have put up with a nudist colony; they didn’t approve, but they didn’t get too agitated as long as no one paraded through town nekkid. That forbearance vanished in the mid-1950s when Koinonia’s leader, the Rev. Clarence Jordan, spoke out on behalf of two black students who wanted to enroll at the Atlanta college that later became Georgia State University. Overnight, the commune became the target of vandalism and violence. Fences were cut and fruit trees chopped down. Koinonia's roadside market was leveled by a bomb. Businesses boycotted the farm’s products and refused to sell it supplies. Klansmen shot into the property and snipers took aim at its houses.

That part of the story is fairly well known in certain religious, academic and journalistic circles. I knew it myself from visiting the farm in the fall of 1980, on my first out-of-town assignment for the Atlanta newspapers, when you could still see bullet holes in one of the older frame buildings. The fresh aspect of the story – at least to me – concerned the children of Koinonia and the hell they went through when they entered the public schools just as the Civil Rights Movement was coming to a boil. One of those children was Greg Wittkamper, the husband of Ann’s friend, who had the misfortune of being the only Koinonia kid at Americus High School the year it admitted its first black students, in the fall of 1964.

I phoned him in West Virginia, where he had lived for decades, and asked whether he would mind talking with me.

“How soon can you get here?” he said.

Greg Wittkamper visiting Koinonia when he returned to Americus for the book launch. The community set out pecan trees when it was being boycotted by the locals during the 1950s and had to find a new way to support itself. It decided to sell pecan products by mail order under the slogan ,"Help us ship the nuts out of Georgia."

Greg picked me up at the airport near the Greenbrier Resort, and we drove half an hour into a remote section of the Allegheny Mountains, where he lived in a rambling hillside house overlooking a pond where he sometimes went skinny-dipping. It was the summer of 2006 and he was almost 60, with gray patches in his beard. Now semi-retired from the real estate business, he was enjoying life with his second wife and their young daughter. He seemed a supremely contented man. But when we sat down on his wraparound deck to talk about his high school days, it didn’t take long for the memories to bring tears to his pale blue eyes.

Greg is a preacher’s son whose father moved the family to Koinonia in 1953 because he wanted to live among pacifists and back-to-basics Christians. When he began grade school, Greg was aware that other students regarded him as something of alien because of where he lived, but he didn’t feel threatened until the night riders started attacking the farm three years later.

One night in 1957 stands out. He and some of the other children were playing volleyball when two cars slowed down on the highway and fired into the court area, sending the kids diving for cover. He vividly remembered seeing tongues of flame flicking from gun muzzles.

“We thought they were going to take us out and hang us on crosses,” Greg told me in his soft, gentle voice.

The conflict between Koinonia and the outside community eventually moved into the public schools. The fellowship had to file a federal lawsuit in 1960 to force the city system to admit three of the farm’s teenagers into Americus High, where authorities feared that their presence would cause trouble because the commune was an open supporter of civil rights. Greg enrolled there the following year.

All of the Koinonia children were harassed in high school, but none of them went through the hazing Greg experienced during his senior year. It started when he showed his solidarity with three of the students desegregating the school by riding to class with them in a limousine provided by a black funeral home. They were met by a mob throwing rocks and spewing hatred. Over the course of the school term, Greg was tripped, spat on, pushed down stairs, hit in the face with a sloppy Joe, called every ugly name in the book and shunned like a leper. He was physically assaulted on two occasions. True to his pacifist teachings, he never fought back.

The year ended much as it had begun. At graduation, in June 1965, Greg was booed as his name was called to collect his diploma, and then a couple of dozen ruffians chased him and his best friend, a young black man, off campus with more rocks and invective.

But something else happened at commencement that foreshadowed better days to come. One of Greg’s classmates, who had become unsettled over the way he was being treated, walked up to him in front of everyone, shook his hand and congratulated him on surviving. His name was David Morgan. Decades later, he was the alumnus in charge of planning the 40th class reunion.

Greg had recently received a letter from David, the first communication they had had since that handshake. He went inside the house and came back with an envelope that contained three handwritten pages.

“I expect you will be quite surprised to hear from me,” the letter began. “If you remember me at all, it will likely be for unpleasant reasons.

“I don’t recall ever directly assaulting you, but I probably did to gain acceptance and accolades of my peers. In any case, I surely participated as part of an enabling audience, and tacitly supported and encouraged those who did. For that I am deeply sorry and regretful.

“Throughout the last 40-plus years, I have occasionally thought of you and those dark days that you endured at our hands. As I matured, I became more and more ashamed, and wished that I had taken a different stand back then. I knew, even then, that it was all wrong, yet I did nothing to stop it, or even to discourage it.”

David’s wasn’t the only letter. Greg had a folder full of of them from people he had never expected to hear from again.

Americus High School was largely destroyed by fire during Greg's junior year. During his senior year, many of his classmates wanted to destroy him.

I could have written a compelling book if I had done nothing more than document the way Greg, Koinonia and their friends in the black community were terrorized during the civil-rights era. That part, sadly, was predictable. The apology letters and the invitation to return for the reunion were unexpected. Seeking forgiveness for something that happened almost half a century before struck me as an extraordinary gesture. I wanted to understand it, to explore how these children of segregation had changed and why they wanted to apologize.

About a dozen classmates wrote or phoned Greg in the spring of 2006. They were not the ones who actually attacked him but were rather the “good kids” who had stood by and said nothing while the bullies – always a noisy minority – hounded him. Their silence reminded me of the white clergy that the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. addressed in his letter from the Birmingham jail, the ones who knew right from wrong but seemed to prize order and tradition more than justice and morality. I wondered whether I would have been among the sheep if I had been a few years older and had been raised in Americus instead of Atlanta. Probably so.

I decided to focus on four classmates who had written the most heartfelt messages: two men and two women. They had all left Americus after high school and had their minds broadened by some combination of college, military service, change of locale or a deepening comprehension of their faith.

David, the reunion planner, had gone on to become a banker in Perry, Georgia. I visited him at his office and later at home and asked him to read his letter into my recorder so we could put it online with the initial feature story I did for the Journal-Constitution. It moved me to hear his eloquent words repeated in such a honeyed Southern accent.

David Morgan, at the book talk in Americus. He was the classmate who planned the reunion and set the reconciliation into motion.

One of David’s pals in high school was Joseph Logan, the co-captain of the football team, who had become a professor at a community college in Enterprise, Alabama, where his attitudes evolved as he began to teach black students. When I went to see Joseph, he was in poor health and seemed to be in a confessional mood. He told me about a night on the streets of Americus when he joined a pack of white guys who assaulted a black man simply because they were angry about civil-rights protests. Joseph hadn’t struck the man himself, but he nearly did, and he considered the moment an epiphany in his life. Joseph died before my book was published. I wish he could have seen how I used his powerful example of a young man finding his moral footing.

The two women I concentrated on had been best friends in high school. Celia Harvey Gonzalez, who was living outside Charleston, had married and moved away and then remarried a man of Spanish extraction who couldn’t believe some of the stories she told him about life in Americus during segregation. Celia was particularly concerned about how I was going to portray her parents’ generation, the adults who had defended the old racial order and tried to force Koinonia to leave the county, going so far as to launch a grand jury investigation of the farm as a communist front. She and I both knew that they wouldn’t be heroes.

Celia’s friend Deanie Dudley Fricks had written one of the most emotional letters to Greg. She was deeply religious and cited scripture about outcasts and persecution, even comparing the silence of her high school class to the silence of Christians during the Holocaust. I caught another glimpse of her sensitive nature this spring, a few weeks before the book came out, when she phoned me on the weekend of the commemorations of the Selma voting-rights marches. She had been watching TV in Albany, where she lives part of the time, and had seen a news program about the Leesburg Stockade, an infamous chapter of the civil-rights saga in which three dozen black girls protesting segregation in Americus were arrested in 1963 and held for weeks under primitive conditions at an antiquated stockade in the next county south.

“I can’t believe that happened in my hometown and I never knew about it,” Deanie told me. “Those girls were about my age. Why didn’t I know about that?”

I tried to reassure her. I told her that I wasn’t surprised she didn’t know because she didn’t go to school with those girls or go to church with their families. The local paper wasn’t covering the protests, and most of the adults weren’t talking about them in front of their children.

There was a long pause. I could tell Deanie was upset.

“That’s my hometown,” she finally repeated, “and I didn’t even know.”

Downtown Americus at dusk

Americus is a contradictory place whose history shows bright flashes of the Old South and the New South. A few miles north of town is the Andersonville prison camp, where almost 13,000 Union soldiers died of disease and exposure during the waning months of the Civil War. A few miles west is Plains, home of Jimmy Carter, whose election as president more than a century later wouldn’t have been possible without the votes of millions of white Southerners and African-Americans. There are few places where the ghosts that still inhabit our region dwell in such close proximity.

When “The Class of ’65” came out in April, Greg and I gave a talk to a large, appreciative crowd at the Carter Presidential Library in Atlanta and then drove to Americus for a presentation there. But first we headed out to Koinonia to visit the place that birthed the story. It’s still there, on Highway 49, the old Dawson road, a working farm with some two dozen full-time residents and many more visitors who come like pilgrims to appreciate its history, its alternative take on Christianity and its dedication to organic agriculture.

Greg and I stood outside the cabin where his family used to live, identified by a sign as the “Wittkamper House.” It was unseasonably warm and the gnats were already dive-bombing our ears. “Welcome to southwest Georgia,” he said. We wondered aloud how the locals might receive the book. Greg had already heard of someone who had made a crack about how he wasn’t interested because it was just something about “those communists.”

We needn’t have worried. The book was received warmly, thanks in part to a sympathetic front-page story in The Americus Times-Recorder. When we spoke that evening at the Lake Blackshear Regional Library, there was an overflow turnout that included several people from Koinonia, Habitat for Humanity and its spinoff, the Fuller Center for Housing. Some of Greg’s classmates made it, including David Morgan, who had driven down from Perry. All four of the students who had desegregated Americus High in 1964 were there: Jewel Wise, David Bell, Dobbs Wiggins and Robertiena Freeman Fletcher. I was pleased to see them, not just because they were an integral part of the story, but because their presence spoke to a question I had considered at length: What do we make of a civil-rights tale whose hero is white?

The four students who desegregated Americus High, at the book talk in April (clockwise from top left): Dobbs Wiggins, Robertiena Freeman Fletcher, David Bell, Jewel Wise.

I didn’t have to wait long for someone to broach the topic. In one of the first reviews of the book, in The Washington Post, columnist Donna Britt came right out and said it: “As a black person, I wondered: Was this another ‘white savior’ narrative – think of the movies ‘Mississippi Burning’ or ‘The Help’ – celebrating a white person’s bravery for supporting beleaguered blacks while de-emphasizing the African-Americans who required courage just to survive? Wittkamper was horribly mistreated. So were his black schoolmates ...”

Perhaps I should I have paid more attention to the struggles of those four black students. I did tell their stories, but only in threads and patches. They were treated horribly, especially Robertiena, a bright, outgoing sophomore who had transferred from the black high school thinking that she could make some white friends if they would only be willing to talk to her. She was shunned as thoroughly as Greg. Then, near the end of her first year, she was arrested on a bogus morals charge – she had been caught in a car necking with her boyfriend – and had to study for her final exams in a jail cell. Despite that nightmare, she remained at Americus High and became the only one of the four who graduated there.

All that backstory was churning through my head during the question-and-answer session after our talk at the library. At one point, I located Robertiena in the audience and told her that her tribulations were worthy of a book in their own right.

“Don’t worry,” she said, smiling. “I’m thinking about doing one.”

Robertiena recently retired as head of the pharmacy at the Houston Medical Center in Warner Robins and has more time on her hands now, so maybe she will write a book. I hope so. There are so many stories of pluck and bravery from those years. I told one of them.

Ultimately, that was enough for The Washington Post reviewer, who ended her meditation on the “white savior” question with this:

“But the more I learned about Wittkamper’s grit, the more I admired him. Courage deserves acknowledgement no matter what color it’s wrapped in. My predominant ‘why’ became ‘Why can’t the rest of us be as brave?’”

On the morning after our talk, Greg and I stopped by his alma mater to take a look around. Americus-Sumter County High School South, as it’s now known, has changed substantially since the first black students walked through its doors in 1964. As integration progressed over the following years, most of the white families pulled out of the public schools and enrolled their children in a new private institution called Southland Academy, leaving Americus High almost 90 percent black. Years later, in a crowning irony, Robertiena’s sister Juanita became principal.

It was a school holiday, and the doors were locked, but we were able to find an open gate and slip onto the grounds. We walked toward the baseball grandstand, a green wood-frame relic of the 1930s, where one of the most dramatic scenes of Greg’s time in high school played out. One of his classmates, Thomas, accused Greg of calling him a bastard and challenged him to a fight after school. Word spread that the kid from Koinonia was finally going to get his butt kicked, and when Greg tried to walk off campus, a pack of boys who wanted to see that happen stepped out from behind the grandstand and blocked his way.

“It happened about here,” Greg said, stopping as if finding his mark on a stage. “They tell me there were about 50 boys, but it felt like the whole school was watching.”

I assumed Thomas’s role and faced Greg with my fists raised.

“So another boy came up from behind and knocked the books out of your hands,” I said, picking up the narrative, “and that was when Thomas took a swing at you.” I made a slow-motion arc with my right. “Exactly where did he hit you?”

Greg pointed to his cheek. “Right here. Hard. It almost knocked me down.”

When I was writing about the showdown at the ballfield, I thought about the fortitude it took to get walloped in the face and not lash back in anger: the self-control, the commitment to nonviolence, the practical calculation that a counterpunch would invite others to join the attack. Now that I was confronting Greg with clenched fists, my viewpoint switched to Thomas’ and what it must have felt like to throw that punch. I could remember only one time in my childhood when I had hit someone, a boy in the neighborhood, over some silly disagreement during a game. I’ve never forgotten the white-hot flash of shame that surged through my head. It actually made me dizzy, as if I had been the one getting socked.

I told Greg about the encounter and how I instantly regretted striking another person. “It’s a hell of thing to hit someone,” I said.

Greg nodded. “I don’t think Thomas really wanted to do it. He looked scared. I think he was just doing what he thought everyone wanted him to do.”

As we stood there reliving the distant traumas of our youth, they didn’t seem so distant, and I noticed that we both had tears welling up in our eyes.

Greg Wittkamper revisiting the ball field at Americus High, where the most dramatic day of his senior year played out, sorely testing his commitment to nonviolence.

The Class of ’65 keeps getting its anniversary dates wrong. The 40th reunion that was the centerpiece of my book occurred 41 years after graduation. The first pass at a 50th reunion took place last year, 49 years after the fact, when several classes were hoping to hold a joint gathering in Americus. After those plans evaporated, some of Greg’s class decided to get together anyway, and they enjoyed it so much that they scheduled another, larger reunion closer to the actual anniversary this year.

The 50th reunion of the Class of ’65 was held three weeks after Greg and I went to Americus to speak at the library. I had planned to go back with him for the occasion, but several of the members I had interviewed politely asked me to reconsider. Their 40th reunion had been dominated by the reconciliation with Greg. Maybe this time, they suggested, we could leave them to each other’s company without the reportorial attention and critical analysis.

I thought it was a reasonable request. I had already written about them welcoming Greg back to the fold. What else did I want – everyone to link hands and sing “Jesus Loves the Little Children”? As it turned out, there was another problem with my attending the reunion: Greg didn’t really want to go.

He had his reasons. Americus is a long haul from his home in Sinks Grove, West Virginia – 560 miles. He had just made the 10-hour drive earlier in the month and wasn’t looking forward to doing it again. More importantly, there was a grave illness in his family. His brother David, his closest sibling, who had accompanied him to the 40th reunion to watch his back, had Stage IV bladder cancer and was about to move into hospice in West Virginia. The whole time Greg had been in Georgia for the book launch, he was afraid that his phone would ring with bad news. It was a cruel twist that one of the happiest times of his life – seeing his story told in a book – would be tangled up with such creeping sadness.

But there was something else. Greg didn’t especially want to go back to Americus for the 50th reunion because, to be honest, he didn’t have much in common with most of his former classmates. He deeply appreciated their reaching out to him before the earlier reunion, and he did feel a closeness with several of the people who had led that rapprochement, such as David Morgan and Deanie Fricks. But he didn’t feel a keen urge to see most of the others. He had made his peace with them – and they with him – and he didn’t think there was much else to say.

Besides, there was another reunion this spring that he really did want to attend. After Greg graduated from Americus High, he was accepted into Friends World College, an experimental Quaker program that sent students around the world to study other cultures. Now part of Long Island University, the school was holding its 50th anniversary celebration in New York City, hosting several hundred alumni at its Brooklyn campus, where they would be put up in dorm rooms.

On the last weekend in May, Greg joined his fellow Friends, many of whom came from alt-cultural backgrounds like his. Although most of them were far younger, they still wanted to know about what had happened to him in Georgia during the civil-rights era and about the book that laid it all out. To them, he was living history, a participant in one of the great social movements of the 20th century. To him, they were kindred souls who felt much more like his true classmates.

“These are really my people,” he said.

While Greg was flying to New York for the Friends World reunion, I was back in southwest Georgia speaking at the Albany Civil Rights Institute, a museum celebrating the movement that in 1961 launched some of the first mass protests against segregation anywhere. So many people were arrested that the authorities ran out of jail space and had to send detainees to surrounding counties – which is how Martin Luther King Jr. came to spend two nights behind bars in Americus. Koinonia was part of that saga; activists considered it a safe haven and used to hang out at the farm and hold orientation sessions there.

As I was preparing my talk, I heard from a woman in Americus who had opened the town’s first bookstore in years, a place called Bittersweet, a nod to the fact that it also serves coffee and chocolate. Elena Albamonte told me that the shop’s first sale had been a copy of “The Class of ’65.” She wanted to know whether I would be willing to stop by for a meet-and-greet after my appearance in Albany. Of course, I said.

I had been at the bookstore an hour when I noticed a vaguely familiar face approaching the signing table. It was Lorena Barnum Sabbs, president of the Barnum Funeral Home, one of the oldest and largest black-owned businesses in town. I had spoken with her several years before, and although she is not mentioned by name in the book, she is closely connected to its events. Her family provided the funeral home limousine that took Greg and the black students to Americus High on the day they were met by a mob in 1964. A year later, it was Lorena’s turn to face the scorn as she started at the school and endured the same sort of daily harassment and name-calling that Greg and the others had put up with. She stuck it out and graduated in 1969.

Lorena told me that had she bought half a dozen copies of the book and given them to her children and other family members in the hope that they would remember where they had come from. I thanked her and asked whether any white graduates had ever apologized to her for the way she had been abused.

“A woman came up one time and said she couldn’t believe the way they had acted toward us. She said it was a shame because we might have been friends under other circumstances.”

“Did she apologize?” I asked.

“Not really.”

I remembered Lorena telling me that she used to run into people around town who had mistreated her in high school. I wondered if that still occurred.

“Not a month goes by that I don’t see one. In fact, I saw one here tonight in this bookstore. They usually act like nothing ever happened.”

I wish I could report that the black students who were badgered like Greg had experienced the kind of reconciliation he has, but I cannot. With a precious few exceptions – one of which plays a crucial role in the book – it has not come to pass.

“I don’t want you to get the impression that I think about this history all the time,” Lorena continued. “I don’t. I love this town, and I know we’re going to get better. But we’ve still got a long way to go.”

As she was talking, I glanced at the front window and saw the bookstore’s name in a new light. How appropriate, I thought: Bittersweet.