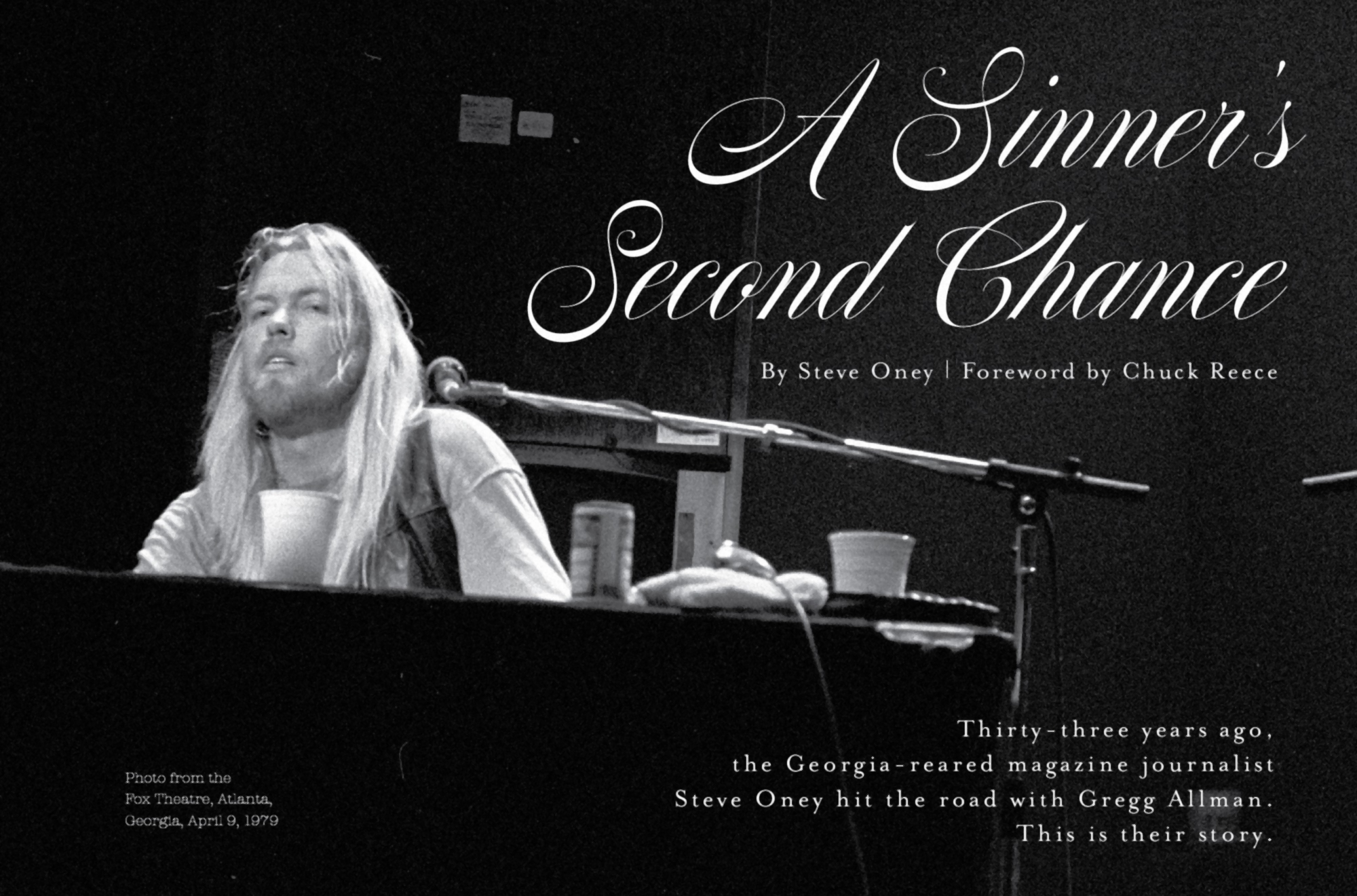

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story was originally published in Esquire magazine in November of 1984. I remember reading it when it came out, and I’ve never read another story about Gregg Allman that I admired more. We asked its author, Steve Oney, for permission to reprint the story here to commemorate the death of the legendary Southern musician. This story is also part of a recently published collection of Oney’s work called “A Man’s World, Portraits: A Gallery of Fighters, Creators, Actors, and Desperadoes.” The story about Gregg, of course, falls into the “Desperadoes” section. As Allman’s spirit floats away, we look back at a time when he faced a big transition in his life.

— Chuck Reece

Story by Steve Oney | Photo by Tom Hill/Getty Images

As the black bus barrels southward, the sun begins to drop below the horizon, and up ahead, far away, the spires of New York City glimmer in the dusk. Gregg Allman, his lead guitarist, Danny Toler, and his pianist, Tim Heding, are sitting around a small table in the front of the coach, with the rest of the band members asleep in bunks at the back. Toler taps Allman on the knee and asks, "Brother, you remember that dream you had when you were nine?"

Allman winces. "If I saw some guy on TV explaining that dream, I'd think he was crazy."

"What was it?" Heding asks.

Allman lights his tenth cigarette of the day. "Well, about the time I was in third grade, I had this recurring dream where I was being led up a high set of steps. At first I thought it was to the gallows. People were behind me, and there were all these bright lights. When I got four steps from the top, I saw a solid block of finished wood — something fine, like walnut. And then I heard this roar. It was a happy sound, like everybody had gotten together for a big barbecue. I jumped up and down, but I couldn't see over the top of that piece of wood."

Allman takes another drag from his cigarette. "I had that dream thirty or forty times then it stopped. I didn't think about it again until years later, when one night at Madison Square Garden I was walking up the steps to the stage and there was my Hammond organ, all shiny and beautiful, and light was coming over it, and the crowd was roaring, and my brother was in front of me. I froze. It was the dream."

But that was long ago. When New York draws so tantalizingly close that Allman can almost reach out and touch it, the bus veers west onto another highway. Gregg Allman doesn't play the Garden these days. Instead, he's headed to a cold little club with concrete slab floors and graffitied plywood walls in Hackettstown, New Jersey, where the band will earn $5,000 then pack up the equipment and head on. In a sense, the job isn't all that different from the kind Gregg and his late brother, Duane, used to take when they were just starting out in the ’60s, playing dates in Mobile, Alabama, and Jackson, Mississippi, on what Allman calls "the chitlin’ circuit ... clubs where we played 'Try a Little Tenderness' to rednecks who wanted to get drunk, listen to music, and get laid — in that order."

At thirty-six, Gregg Allman has returned to the road, hoping that it will lead him back from obscurity. This current trip is a swing through the Northeast. The shows, for the most part, go unnoticed, but Allman is here with friends who have stuck by him through very hard times, and he is determined to make the most of it.

Typical 1984 Crowd at the Channel

In Boston, he is playing the Channel, a cavernous club in a warehouse district near the water. The Channel's regular patrons are more accustomed to the cacophonous grating of Black Flag than to Allman's stock-in-trade — Southern blues — but this evening the crowd is different. Wandering among scores of kids who can't have been much older than ten in 1973, when the Allman Brothers Band headlined the Watkins Glen music festival in upstate New York, are women with long, center-parted hair and cosmic gazes and bearded, balding sorts reminiscent of the Zig Zag rolling paper man. When Allman walks onto the stage and takes a seat behind his organ, applause erupts. The singer smiles, waves, and then, counting off the beat, begins playing a blues progression. At the last possible instant he pulls the microphone to his lips, and in a jagged but mournfully sweet voice that both cuts and caresses, growls, "Just one more morning … I had to wake up with the blues," the opening lines from "Dreams," a song that appeared on the Allman Brothers' first album. No matter what toll the past years have taken, Allman is still the blackest white boy ever to sing about being done wrong.

It promises to be a powerful performance. Things move right along, the band "in a groove," as Allman likes to say, until someone in the crowd accidentally knocks a drink over into the snake — an electrical junction box at the front of the stage that connects nearly every important wire in the band's sound system. Suddenly, half the speakers go dead. Then, as technicians struggle to correct the problem, another disaster strikes. Guitarist Danny Toler sets his instrument down and rushes out the club's back exit, where he falls to the ground, violently sick.

Allman apologizes to the audience and, after tucking his sweat drenched hair down the back of a black leather jacket, makes his way out to the tour bus, where he finds Toler, his face ashen, curled on the sofa in his compartment at the back. Toler, who has played with Allman since the late ’70s, is the singer's closest friend.

Immediately the driver puts the bus in gear and speeds away through the empty, late-night streets toward the nearest hospital.

"Tell him to hurry, Gregg," Toler moans.

"I will, my man." Allman stares off an instant then muses, "You know my granddaddy used to say, 'If you have one friend in life, well, you've been a successful man.' I've been successful all right." Whereupon in an exaggerated Dixie drawl meant to conjure a grizzled old man he adds, "Alfred. That was my granddaddy. He ran a sawmill in Tennessee, but it was a front for a still."

Before Allman can go on with the story, the bus arrives at the emergency room, and Toler is taken off in a wheelchair. As his band mate disappears through the hospital doors, Allman urges the driver to get him back to the hotel, where he's going to see about scraping together a hundred dollars to pay for his friend's treatment. When the coach brakes to a halt in front of the forlorn Bradford Hotel, Allman bounds out and heads up to the eighth floor, where he finds a small mob of ready-to-party roadies and hangers-on gathered in the hall.

Tonight Allman's in no mood to celebrate. Then someone tells him that the group's insurance will pay for Toler, and someone else mentions that the hospital has called to say that nothing is seriously wrong with the guitarist. It takes a second for this to sink in. When it does, Allman locates in the throng a tall, raven-haired woman who bears a striking resemblance to his ex-wife, Cher, takes her by the arm, and smiling, steers her down a long hall to his room. Things, as he well knows, could be worse.

It is now difficult to remember that just ten years ago, with five platinum and three gold albums to their credit, the Allman Brothers were the highest paid rock act in America, often earning $250,000 a night. The group's sound was powerful, original, and perfect for the times — bluesy yet psychedelic. While fans seemed to be transported first and foremost by Duane Allman and Dickey Betts' guitar duets, it was Gregg Allman who gave the Allman Brothers their soul. He wrote nearly all of the Allmans' trademark songs and sang all but two or three. "People don't give Gregg enough credit," says Phil Walden, who was president of the Allmans' label, the now-defunct Capricorn Records of Macon, Georgia. "He was really the heart of the band. He knew the blues."

The ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND, 1969. From left to right, dickey Betts, Duane Allman, Gregg Allman, Jai Johanny JOHANSON ("Jaimoe"), berry oakley, and butch trucks.

Not only did Gregg understand black music, but he taught it to his brother. It was in the early '60s that the two boys formed their first band, the House Rockers, and started playing backup for a group of black singers, the Untils, on the boardwalk at Daytona Beach, Florida. Then after a short stint with another hometown band — this one named the Allman Joys — the brothers found their way to Los Angeles and started a psych-pop band called Hourglass. By late summer 1969, the two were in Georgia, where Duane, who had established himself as a leading recording session guitarist, organized what would become the Allman Brothers. Soon the group recorded an album and started playing free concerts in public parks across the country. Then the band took off. But that, too, was a long time back.

A couple of nights after the disaster in Boston, the band is headed to its next gig, this one in Baltimore. As the tour bus barrels down Interstate 95, Allman has retreated to his private quarters, where he is cradling his Gibson Dove in his lap. He is in an unusually talkative and reflective mood, and between sips of lukewarm ice tea he bought fifty miles ago, his mind roams backward. "Man, I remember Watkins Glen like it was yesterday," he says.

"I'd never been so scared in my life. We helicoptered into the place, and when we got near all you could see were people. It was a sight."

A radio recessed into the compartment's back wall is playing faintly, and it picks up the strains of a song by Prince.

"That boy ain't got no chops," Allman snorts. "He sure ain't no Little Richard." Then Allman smiles.

“When I met Little Richard the first time, it was around when our Fillmore East album was set to come out. I'd been to New York and bought myself some beautiful clothes in the Village — floral-patterned shirts, boots, bell-bottoms. And I'd bought this incredible belt buckle — a shiny, outrageous thing. Anyway, I went to see Little Richard in Atlanta. I idolized him. I got backstage and walked up to shake his hand, and he grabbed that buckle and just smiled at me.

"I said, 'Mr. Penniman, I'm honored to meet you. I'm an admirer of yours. But if you do that again, there's gonna be a dead nigger here.' We've been great friends ever since."

Allman chortles. Then, his voice straining into a high register, he begins singing, "Tutti frutti, aw-rootie, tutti frutti... "

Coughing, he grins and adds, "I'll tell you who can outdo Prince and Little Richard. That's Little Milton. I finally met him, too. Only one I didn't meet was Otis Redding."

Allman takes another sip of tea. Although he never knew Redding, Gregg inherited both musical and corporate sustenance from the late soul singer. Redding was the first star managed by Phil Walden and booking agent Alex Hodges out of Macon. Walden and Hodges used what they learned handling Redding to build a music empire in an otherwise backwater middle-Georgia city. By the mid-’70s, Capricorn Records was a force to be reckoned with, and it was no accident that Georgia governor and presidential aspirant Jimmy Carter eventually sought Gregg out.

As the bus rolls on, Allman is still reminiscing. "Back in the fall of ’74, Jimmy Carter threw a party for Bob Dylan one night at the governor's mansion. I got there late, right as the last guests were going home. I had my limo driver stop at the gate, and the guard told us to come on. Carter wanted to see me.

“We drove on up to the front porch, and Carter was standing there on the steps, wearing old Levi's, a T-shirt, and no shoes.

“We went inside and sat down on the floor. We talked for a long time. I genuinely liked the man. Still do. He told me he was going to be president, and I started laughing. But he was serious, and he asked me to help him raise some money."

By the time Allman agreed to promote Carter, he had released his first solo album, “Laid Back” — a work that to date is his creative high water mark. Not only did the record include a hit ("Midnight Rider"), more important it contained Allman's most ambitious and successful effort as a songwriter, a demanding, disturbingly sad blues ballad called "Queen of Hearts."

Reaching into his wallet, Allman extracts a dog-eared Bicycle playing card — the queen of hearts. "That song saved my life. It gave me a sense of ... for the first time I realized I wasn't the no-talent, procrastinating, don't take-care-of-business flunky sheep I thought I was after my brother died." After things began to fall apart.

Allman sighs. Then he glances up sullenly and mumbles, "I can tell you some crap to make your hair curl. Once, I got myself off in the dark." He makes a muscle with his left arm then mimes giving himself an injection just above the elbow. For a second, deep furrows become visible around his eyes. Soon, he falls asleep.

In the fall of 1971, when Duane Allman was only twenty-four, he was killed in a motorcycle wreck in Macon. Accompanying himself on acoustic guitar, Gregg sang "Melissa" to the hundreds of mourners at the funeral, and then everyone joined in on "Will the Circle Be Unbroken."

Gregg & Duane Allman

A year and thirteen days after Duane's death, Allman Brothers bass player Berry Oakley died from injuries sustained in a motorcycle crash only a few blocks from the intersection where Duane perished.

Never averse to taking whatever drug was put in front of him, Gregg began indulging a heavy cocaine habit. In 1976, after John "Scooter" Herring — the road manager who supplied Gregg's needs — was arrested, Gregg turned state's evidence, testifying against his friend in federal court. ''They had me. I had to do it, and Scooter understands," Allman said. But other members of the Allman Brothers weren't so forgiving. Drummer Jaimoe Johanson wrote an open letter to Georgia newspapers contending that Gregg's actions had destroyed the band. Lamar Williams, the group's new bass player, said, "He really hurt everybody … I could never work with him again." On a wall near the offices of Capricorn Records, an anonymous protester scrawled: GREGG ALLMAN HAS MURDERED THE BROTHERS AND ROCK 'N' ROLL.

Things went from bad to worse. Shortly before the Herring trial, Allman exiled himself to Los Angeles, where he'd met Cher one night after she'd seen him perform at the Troubadour. Following a passionate courtship, Cher became his third wife in a ceremony conducted at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. Nine days later she filed for divorce. The couple reconciled long enough to produce a son, Elijah Blue, and one of the worst albums ever recorded: “Allman and Woman: Two the Hard Way.” In 1978 the marriage broke up for good. Cher recently said she doesn't care if she ever sees Allman again and that he never calls to check on their son. When asked about Cher, Allman said plaintively, "I still love her. I always will."

Allman had used heroin before, but by the winter of 1977 his addiction had become so bad that he sequestered himself back east in the house of a Buffalo physician who, in exchange for $29,000, promised to step him down. For several weeks, Allman used methadone. Then he went cold turkey. For days he managed only a few hours' sleep, brief interludes disturbed by dreams of gore and dismemberment. But mostly, Allman was wide awake. It was the winter of one of Buffalo's worst blizzards, and he spent almost all of his time walking up and down four flights of stairs in the old house, watching the snow pile higher and higher and feeling his habit freeze over.

After fifty days of treatment, Allman was clean, but his life had become a melodrama, and soon he sank into alcoholism. The first thing he'd do most days was upend a quart of vodka. ("Some mornings I had to use a straw, I was shaking so bad.") Always shy and laconic, he grew downright prickly. "He was nice one minute and mean the next," recalled Danny Toler. "He was distant and unreliable," said Phil Walden. Allman put it more succinctly: "I was an asshole."

The gregg allman band, 1977.

During the next five years Allman was in and out of alcohol abuse centers all over the country, and he joined Alcoholics Anonymous. Yet somehow, in the midst of everything, he managed to reunite the disbanded Allman Brothers and record a final Capricorn album. The band then moved to Clive Davis and Arista for two uninspired albums. Davis and Allman feuded over creative control, and the records failed miserably. To top it off, deep wounds still festered in several band members because of the Herring trial. After an appearance on “Saturday Night Live” in 1982, the group disbanded for good and Allman repaired to his new home near Bradenton, Florida.

Save for a few fanatics — freaks with their flags still flying, blues musicians with whom Allman occasionally jammed in Atlanta, and those fans who remembered how superb Gregg was in his prime — many people forgot Allman ever existed.

In Baltimore the band plays an imitation Gilley's then it's on to a suburban shopping plaza hot spot in Columbus, Ohio. For Gregg Allman, the discouragement he is experiencing now is at least better than the despair he was feeling sitting idle at home. "I just got sick and tired of being sick and tired," he says. "I discovered I didn't have to hurt myself to live. I'm ready to be a top entertainer again. I want to have hit songs on the radio."

Wishing, however, isn't necessarily going to make things so for Allman, although from all accounts he has dried himself out. Allman's renunciation of liquor is regarded by several key members of the supporting cast from the Allman Brothers' glory years as an important sign. Veteran manager Willie Perkins, someone who loves Gregg but had given up on him, has returned to the fold. Alex Hodges never really lost faith in the singer, but lately he's intensified his efforts on Gregg's behalf.

From Hodges's offices at ICM in West Hollywood (and from the Atlanta suburb of Marietta, where Hodges headed up the Empire Agency before moving to the West Coast last spring), calls have been going out for months now to record companies in Los Angeles and New York. A balding, meticulous Southerner with an affinity for bird hunting, Hodges says, "What I've found is that there are a lot of roadblocks out there. They know Gregg's got a great voice and know he's got a following, but we've got to show them some great new songs, and then there are the perennial questions: How's his attitude? That means, Is he straight? And is he the classic artist of the '70s who's just not going to be able to make it in the music world of the '80s? The answer to the first question is yes and the second is no."

Still, as Lenny Waronker, president of Warner Bros. Records, puts it, "Gregg may have a chance to make a comeback, but it's a real judgment call. When he's clean, he's great. When he's not straight, he's just not focused or motivated."

Yet Hodges labors on. There's a possibility that CBS Records might sign Allman, but Hodges wants to guard against the chance that the label will regard the singer as an old war-horse. Then there are several so-called P&D deals in the air with relatively unknown labels that would require Allman to pay for his own production work in exchange for distribution. Finally, Hodges has even considered a television direct-marketing deal with a company along the lines of K-Tel. Hodges says that the TV group "wants to break the mold," but if that's the road he takes, it's hard not to envision Allman becoming a rock 'n' roll Slim Whitman, his records advertised late at night on Atlanta Superstation WTBS.

What Hodges has to offer record companies is an eight-song demo tape Allman and his band recorded in a small studio in Sarasota, Florida. Allman's new songs are good, and his voice is better than ever, but as one record insider puts it, "I just can't hear them on the radio." Phil Walden, who rarely speaks with Hodges (the two old associates have been embroiled in acrimonious disputes concerning the breakup of Capricorn), says, "Gregg's getting bad advice. He's such a great singer, but they've got to push him toward a more modern sound." Indeed, on careful listening, Allman's tape reveals that he's relying on the same arrangements that worked for him in the old days: two percussionists, two lead guitars, and a lot of the blues. If his sound has progressed at all, it's in the direction of the soulful fusion of such mystic redneck bands as the Dixie Dregs.

Of course, whether Allman signs a lucrative new deal or not, he will remain one of America's great blues musicians, and if he wanted, he could build a career as a white B.B. King. In fact, Allman appeared with King last summer at the Medgar Evers festival in Mississippi for a memorable jam session, but as Allman looked around that day he must have realized that he was the only young man on the stage.

Allman says he doesn't want to go out as yesterday's news. But he's got a lot of ground to cover just to catch up with the present, much less plan for the future. It's no surprise that Allman, a product of the era of Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin, the little brother of a rock 'n' roll martyr, would have his own romance with Thanatos. Now, after winning a hard-fought battle with drugs and liquor, he's embracing the idea that life is good. The clubs he's playing may be small, and the hotel rooms may be steerage class, but Allman — who’s redefined the cliche about paying your dues to sing the blues — doesn't mind. No one ever promised him that it was going to be easy.

On a sunny late winter afternoon, Gregg Allman sits on the set of "Thicke of the Night" at Metromedia Studios in Hollywood. He's making a guest appearance in the hope of letting fans and record magnates alike know of his reemergence. But "Thicke of the Night," one of the only shows in recent memory to flirt with zero in the Nielsen ratings, isn't exactly the perfect showcase. Appearing with the singer are the busty female publisher of High Society, who's pushing her new phone sex business; the film critic of The Hollywood Reporter, who's gushing about a couple current releases; and a white-haired psychic named Kenny Kingston, who's trying to communicate with Marilyn Monroe via a tiny artifact that he claims is one of her fingernails. As Alan Thicke prattles with his guests, Allman — perched at the far end of the banquette behind the host — plays nervously with his hands and stares at the floor. Finally, just before Allman and Danny Toler, who's waiting in the wings, are scheduled to play a couple of songs, Thicke turns toward the singer.

"I've read you don't like to do interviews, Gregg. What do you like to do?”

"Oh, I like to fish," Allman manages.

"Well, Gregg, that's why they ask you about Cher. They're afraid you'll want to talk about trout."

Following a couple of other equally inane exchanges, Thicke allows Allman to perform his songs. He's impressive.

Afterward, Allman and Toler retire to their room at the Hollywood Holiday Inn, another unimposing hotel in yet another unsavory part of a big city. Before ordering room service, Danny changes into his pajamas and Gregg unbuttons his jeans, unleashing the beginnings of an unruly gut.

Eventually, steaks, potatoes, fruit salad, and a huge container of ice tea arrive. The two silently wolf down the meal as a TV buzzes on the wall. Finished, they push the room service cart aside, and Danny tosses a couple of Frisbee-like plastic plate warmers onto a corner chair. Only seven years before, Gregg was retiring in splendor at Cher's Holmby Hills mansion about ten miles to the west. Now it's barely eleven o'clock, but he pulls a faded bedspread up to his chest. "I'm beat," Allman says emphatically, and Danny gets up and flicks off the TV.

Steve Oney is the author of "A Man's World, Portraits: A Gallery of Fighters, Creators, Actors, and Desperadoes."