Inside Atlanta’s Center for Puppetry Arts, dedicated crafts people for more than 40 years have pulled at our heartstrings. Consequently, the Center has become the hub of the entire wacky world of puppetry, not only in America, but also across the whole planet. Not to mention the fact it’s where Kermit lives these days.

In a former school building in the heart of midtown Atlanta, couched in the shadows of two titans of the city’s art scene, SCAD Atlanta and the Woodruff Arts Center, there is a portal to a world of illusion and magic. Inside its modest doors, children and families are transported to a place where the trials and tribulations of everyday life are suspended, and childhood splendor reigns supreme, suspended by felt, foam, wood, and string.

I’m speaking of a curious institution, the likes of which no other city in the United States can claim: the Center for Puppetry Arts.

The world of puppetry — and it is a whole world — is an insulated one, partially from the perfect storm of artistic talent it takes to become a master puppeteer.

“In puppetry, there’s a long tradition of the puppeteer doing it all — crafting their own world,” says Kristin Haverty, who works as producer with the Center. Like sculptors, puppeteers whittle, glue, and shape memorable characters out of everyday objects. Like actors, they evoke multidimensional personalities on the stage. Like dancers, they express a myriad of emotions through movement.

All these elements are necessary to breathe life into an otherwise inanimate object.

“The puppet is the key element,” says the Center’s artistic director, Jon Ludwig. “The other element is the audience’s disbelief. To suspend what is rational, the knowledge that the puppet is not alive. You know it’s not alive, but yet it has the traits and qualities of life that transcend theatrical experience. A puppet — it’s pure imagination. That’s the mystery and delight. Kermit is as real as your congressman, maybe even more real.”

An array of puppets at Raymond’s shop.

This artistry has made icons of both puppets and puppeteers for centuries, worldwide. Puppetry has been responsible for some of the most memorable moments in film, television, and stage performances in recent western history. It led us to mystified terror in Aliens and Jaws; it delivered us to existential crises in Being John Malkovich; it filled us with wonder in The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth; and it became larger than life in the Broadway productions of “Warhorse” and “King Kong.” And, of course, it helped raise us and bring us joy with “Sesame Street,” “Howdy Doody,” and “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.”

Though the prevalence of computer-generated imagery (CGI) has overshadowed the historical art in today’s entertainment, practical effects and puppetry remain timeless and necessary in film, television, and theater. Now, with Netflix reviving revolutionary works like The Dark Crystal, a revival seems afoot.

“There has been a boom of practical effect coming back,” says a puppeteer and former pupil at the Center, Raymond Carr. His experience there led him to Hollywood, where he has worked on projects with The Jim Henson Company and Nickelodeon, among others. “They tried to see how close they could get to practical effects with CGI. But it’s gotten to a point where, well, nobody gives a shit that you can make a photorealistic tiger on a computer anymore.”

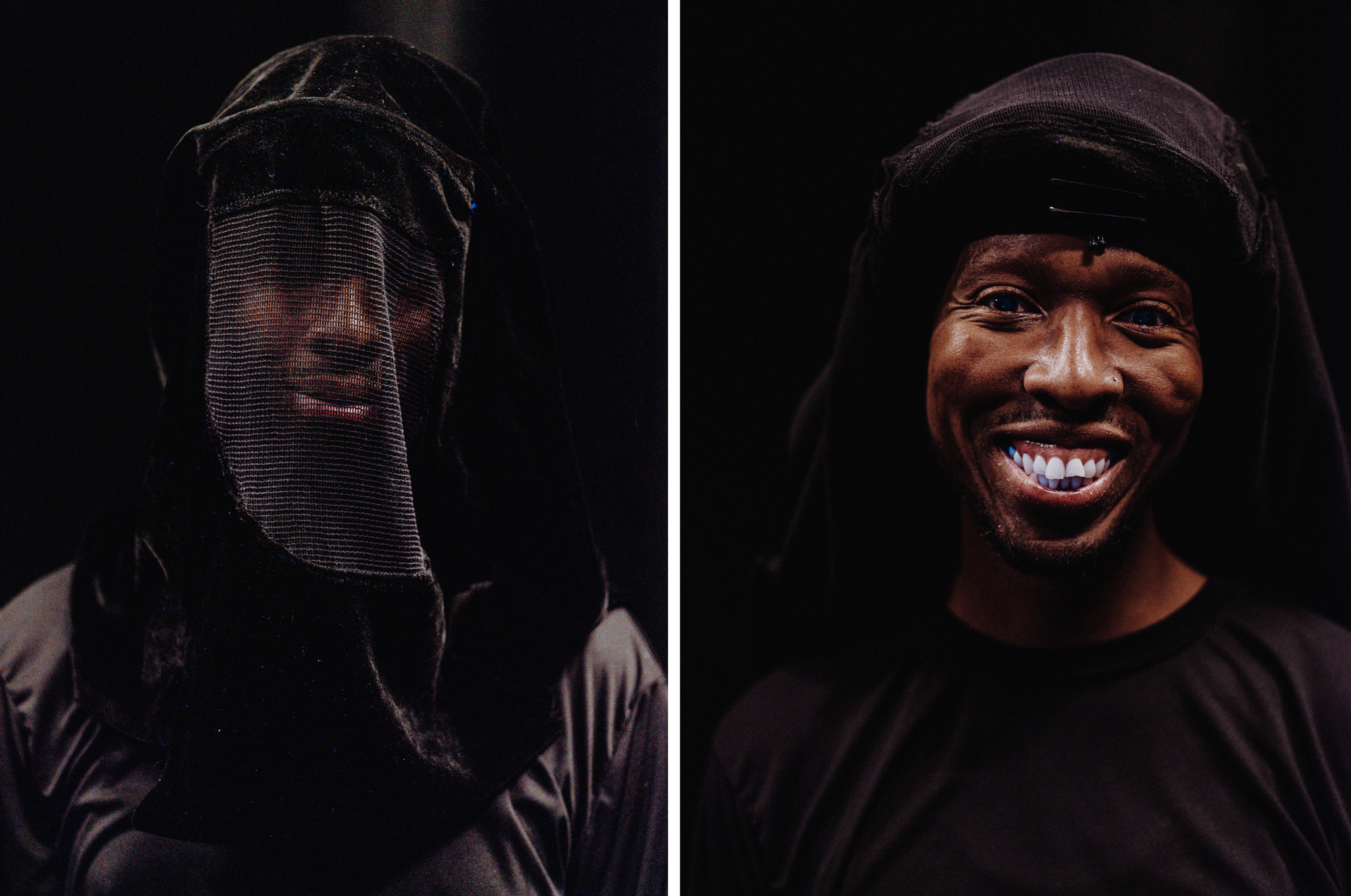

Puppeteer and former pupil at the Center, Raymond Carr

In the context of the puppetry world at large, a subculture with roots that go back centuries in every corner of the world, the Center has a reputation of considerable acclaim.

“Puppetry has always been marginalized. That’s the nature of it, the way the puppeteer hides, that it’s self-effacing to a degree. That may speak to the profile of the Center’s role in Atlanta,” says Basil Twist, heralded puppeteer and recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, aka the Genius Grant. “But there’s nothing even close to [the Center] in the United States. People might assume there’s something bigger than it in New York, but there’s not. Atlanta is where the heart, soul, and brains of the puppetry community are in this country. And compared to the other institutions I’ve been to in France, it is no small potato. It’s an important institution.”

Twist isn’t alone in his regard of the Center’s role in the world of puppetry. Along with fostering his talent — he interned at the Center in the 1990s — many other high-caliber talents have gone on to flourish in the industry after working with the Center. Former pupils and interns include Carr, Peter Linz, Ronald Binion, Alice Dinnean, and Lucky Yates.

Imagination reigns supreme in the world of puppetry, and in turn at the Center for Puppetry Arts. No idea is outside the realm of possibility. Because of that, the Center, for more than 40 years, has continually been a place where creativity for all ages takes root and thrives.

In 1962, Atlanta’s arts community was decimated by the Orly Crash, a disastrous incident in which 122 of the city’s local arts patrons perished in a single flight to Paris. From the ashes of that heartbreaking incident the Atlanta Arts Alliance took shape. By 1968, the city’s art museum — which later became known as the High Museum of Art — had evolved into the Atlanta Memorial Arts Center, a place where theater, visual art, and classical music could rally together in one permanent footprint.

The 1970s was a time of great excitement and growth in Atlanta’s arts community. By 1979, former Coca-Cola Company president Robert W. Woodruff challenged the city to build a “museum big enough for Atlanta,” pledging a $7.5 million match to the cause. The city exceeded his expectations and raised $12.5 million for the new building.

To say that there was significant energy around the arts at the time would be an understatement.

Vincent Anthony, now the Center for Puppetry Arts’ president and executive director, took notice. Back then, Anthony was a touring puppeteer. After studying under Nicholas Coppola in New York, he spent two years touring with Coppola’s Nicolo Marionettes in schools, libraries, community centers, small theaters, and church basements across the United States. By the mid-’70s, Anthony had become president of the Puppeteers of America.

“We were planning a major international event for Washington. D.C. — the association (UNIMA-Union Internationale de la Marionnette) has a festival and congress in a different country every four years like the Olympics,” Anthony says. During the time of planning for the 1980 World Puppetry Festival, Anthony was living in Atlanta and planning the festival while also performing at the Woodruff Arts Center. “In order to put [the festival] together, we had to work with Jim Henson, Nancy Staub, and Allelu Kurten.”

Vincent Anthony, the Center for Puppetry Arts’ president and executive director

The festival would be an all-encompassing celebration of puppetry. International artists would gather for special performances. Museum exhibits would be staged to celebrate the varied techniques and worldwide history of the art form. And classes and workshops would lift the veil a bit and teach intrigued and inspiring puppeteers more about the art. While planning all this, Anthony came to a jarring realization of his own. “I realized that all of the ideas we had would all be gone after the festival. I wanted to have an ongoing space for that activity.”

Coincidentally, in the following weeks, space became vacant in the arts district: The former Spring Street Elementary building already housed the offices of the Atlanta Ballet and a few other arts organizations. When one of its spaces opened Anthony saw an opportunity.

By late September 1978, preparations were in place for the Center to have its grand opening. Anthony took the initiative to visit a close friend about the opening festivities — a little green frog named Kermit, and the man who introduced him to the world, Jim Henson. Henson, at the time, was filming The Muppet Movie in Los Angeles.

“He loved to have people watching him work, especially other puppeteers,” Anthony says. He watched as Henson filmed his Muppets gathered around a great campfire in a fake desert. Afterward, they went for lunch, and Anthony invited Henson and Kermit to come and cut the ribbon. Henson contemplated for a moment before responding: “Well, Kermit will be there, and maybe he’ll bring me along.”

For any child of the ’70s or ’80s, walking through the Center’s museum display of the Henson Collection is a euphoric dive into childhood nostalgia. Around every corner waits another old friend — cultural icons like Grover, Oscar the Grouch, Miss Piggy and her main squeeze, Kermit, and even the hoagie-smoking King from Hey, Cinderella!

“The global appeal of Jim Henson’s creations is not new, though it continues to grow,” reflects NPR correspondent and long-time Atlanta arts reporter, Lois Reitzes. “Not everyone knows that a large population of Jim Henson’s puppets resides in Atlanta. That is because of the friendship between Vincent Anthony and the Hensons.”

Henson’s lasting influence on the world of puppetry, as well as his lasting friendship with Anthony, is apparent from the first step inside the Center, where Big Bird’s nest greets the organization's 125,000+ annual attendees. From there, a bona fide Henson bonanza ensues. The Center expanded its building in 2015 and dedicated about half of its new space to the Henson Collection, which reflects the experimentation, imagination, and generous spirit of the man behind the Muppets. But even after the expansion, only a portion of the Center’s holdings are on display. The Henson collection includes over 500 items, but for the longevity of the puppets, fewer than 20 percent are on display at a time. The Muppets are rotated every six months.

The Center’s Henson Exhibit is meant to recreate the imagination, ethos, and energy of a working Henson set.

For Vito Leanza and Russ Vick, who work as puppet builders in conservation at the Center, the rarities are the true gems.

“Russ and I, every day, feel like it’s Christmas in this room,” says Leanza. Leanza’s exuberant personality is contagious. “I almost cried the first time I saw Grover.”

Carr, the puppeteer and Center alumnus, says, “Jim really did dabble in everything, including experimental film. They truly do have the largest collection of Jim Henson material in the world. I was working on the Henson lot — they don’t have a fraction of what the Center does as far as archival puppets.” By including some of Henson’s less ubiquitous creations, the Center’s collection also encompasses his global vision for puppetry. “You can see the juxtaposition of the world’s standards — from Asia, Africa, and Europe, and then walk into the next room and see how Jim has allowed those outside influences to create his work,” Carr says.

“Some of the other museums chose the more famous things,” says Leanza. “I think we are so lucky to have so many one-of-a-kind puppets that were made for 30-second shots and then put in a box for 40 years.” As we spoke, Leanza sat at his desk with notables from the USS Swinetrek. The office of a puppet builder working in conservation looks exactly as one would expect: It’s filled with dismantled puppet parts in various stages of restoration. A freshly cast puppet hand sits on a desk; a vacuum cleaner with a brush attachment is used to tidy up another work in progress. Above the desk are pliers, tweezers, and stuffing, plus latex gloves, scissors, a kaleidoscope of threads, and needles in a pincushion shaped like a tomato. Leanza, who is known to wear multiple pairs of reading glasses when he’s digging into a project, specializes in conserving Muppets made of felt and foam. His compatriot, Vick, focuses on latex conservation and did most of the heavy lifting when it came to many of the puppets from The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth back to their former glory.

Jeremy Villines, Technical Director

“My favorite puppet I got to work on is a dragon named Butane,” says Leanza. “He was in a pilot of a TV show called “Puppetman” for CBS — a show about live puppet performers on a children’s TV puppet show. Butane was one of the puppets on the show-within-the-show. But it never got picked up.”

Leanza walked a winding path to puppet building. After working for Disney, Leanza made a leap of faith and moved to New York in 1995 to make a go of becoming a singer and dancer. There, he worked with Poko puppets and Larry Engler for 10 years, eventually working his way into creating puppets himself and crossing paths with Bonnie Erickson, the mind behind Miss Piggy, who eventually guided him to the Center. In the insular community of puppetry, such coincidences seem somewhat commonplace — a guiding hand in the right place at the right time, a willingness to share connections and create opportunity. The generous spirit of this community shines most brightly in the Center’s efforts to foster the talent of fledgling puppeteers.

Vito Leanza

Crockett Johnson’s classic children’s book, Harold and the Purple Crayon, has captured the hearts and imaginations of young readers since it was published in 1955. The premise is simple enough: A 4-year-old boy named Harold goes hog wild with a purple crayon one night, when he yearns to go on a walk in the moonlight. Armed with only a purple crayon and his imagination, Harold spends most of the night frolicking in the world he illustrates around him. He draws the moon, and the moon shines. He draws cities, a boat, trees, monsters — and they all come to life. It’s a story that has inspired even more books, plays, films, and television shows — and this year, an original puppet show at the Center.

The energy surrounding the Center’s play adaptation of Harold and the Purple Crayon is electric and a little anxious. This is for good reason. In selecting this classic children’s book to interpret, the team presented itself with some complicated problems: They needed to find a way to make it look like Harold was drawing the world around him in real time, and they needed to do so without letting the audience see the puppeteers standing behind the screen they were projecting onto. To accomplish this, they blended video projection, blacklight puppets, and an 1860s theatrical technique called Pepper’s Ghost.

Harold and a few of his creations in progress.

The Center’s production manager Gregory Montague explains this classic technique. “The trick works off the premise of reflection in glass,” he says. “If you take the windshield of your car in the dashboard, you see the reflection of what’s on your windshield, and it looks like it’s in front of you.” From the audience, it appears as if Harold is magically drawing in the air around him and his illustrations are coming to life. From behind the stage, there’s a reflective substance between the audiences and the performers on-stage. That reflective substance is what video is projected onto. This is only possible without direct light — the image is bouncing only in a single direction. That may cause you to wonder how the performers can see what they’re doing from behind-the-scenes. That’s where things get even more complicated: “For the performers on stage to see what they’re doing, we have to also do it in reverse,” Montague says.

Making blacklight puppets was no small accomplishment, either.

“It’s a tricky project to work on,” says puppet builder Jason Hines, who designed and helped build Harold, along with many other puppets in the show. “Purple is probably the hardest color for black light, and mixing paints make them work less well. But what we have now is so much better than it used to be. The white we had used to look bright blue. At least now it actually looks white.”

Getting just the right hue of purple to show up in black light is no small task. A few years ago it would have been impossible.

Despite having to overcome these aesthetic challenges, using blacklight was best for the job of convincing the audience that Harold is floating in midair.

“This show was a natural progression from shows we’ve done before,” says Montague. “We used video integration with blacklight puppets before with “Little Noodle.” With Rudolph, we used video integration under white light, and integrated edge blending.”

It takes three puppeteers to operate Harold. The little boy whose imagination runs wild with a purple crayon is a tabletop puppet — what some would call Bunraku, a Japanese method of building puppets. The little boy’s head is large and cast in neoprene resin. His much smaller body is constructed mostly of foam.

“That makes it sound fairly simple,” says Hines, “but you’ve got one person who works the head, one person is on the arms, and one on the feet. The person doing the head is also in charge of the drawing. It’s really like ballet back there. It’s hard to script those things.”

“When rehearsals started, we knew it would be different,” says Brian Harrison, one of the puppeteers working with the Center on the show. “Incorporating these techniques together had never been done before, and they weren’t quite sure it would work. We were going through rehearsals just hoping it would translate.”

Some of the cast of Harold and the Purple Crayon

To test the blending of all these techniques, Jon Ludwig, the Center’s artistic director, worked with Hines and Montague to build a diorama of the set — at scale — to test it out.

“We made mock-ups, tried animations, bouncing them into the effect, and it really worked!” says Ludwig. “No matter where Harold is holding it, no matter where you’re sitting, it looks like he’s drawing right there in front of you. It’s fun to combine things that are new.”

Ludwig believes combining all these styles is a responsibility, given the Center’s standing in the world of puppetry.

“It’s the Center for Puppetry Arts,” he says. “We need to pick the style that works best for telling the story. We need to be intentional about how we illustrate it, make it come to life from the page and turn it into something dimensional. Some companies use all marionettes, but for us, well, we’ve always combined styles.”

The puppeteers behind Harold, if they are doing their job right, are barely noticed by the audiences they entertain. (Pictured: Reay Kaplan, Brian Harrison, Jake Krakovsky, Jimmica Collins, & Tim Sweeney)

For the performers involved, the experience of taking part in such a show and learning so many techniques was transcendent. For the audience, it was a wholly otherworldly and transportive show. The Center succeeded in breathing life into Harold, just as Harold had first done with his first crayon over 60 years before. Behind the scenes, it might seem chaotic. Multiple projections — those on the stage and behind the veil — had to happen simultaneously while the four black-clad and masked puppeteers scrambled around one another, moving Harold and his newfound friends across the stage.

None of the bedlam translated to the crowd, though. To them, Harold was simply alive — the glory of the little boy’s imagination took hold, and they were there with him, in a world of his own creation.

“When you’re creating a show, you don’t know what will work until you’ve had an audience,” says Harrison. “Their response surpassed anything we could have imagined.”

Since it first opened in 1978, many of the Center’s interns, XPT alums, and performers of the Center have gone on to reach some level of acclaim in their field. After working on-stage at the Center, actor Lucky Yates first found his big break with The Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland before eventually finding his way into the world of animation, where he is now the voice of Dr. Krieger on the Emmy-award-winning show “Archer.” Peter Linz went on to become the voice of Walter in the 2011 film The Muppets and is now the voice of Herry Monster and Ernie on “Sesame Street.” Ronald Binion has gone on to work on not only on the 2016 reboot of Ghostbusters and the television show “Community,” but on Broadway productions of “Ghost” and “Pippin’” as well.

But few in the world of puppetry have reached the level of acclaim of Basil Twist. In the world of theater, Twist is a bit of a legend. The MacArthur genius and third-generation puppeteer has reached a level of success few others can lay claim. His trophies include the Jim Henson International Puppetry Award, an Obie, Drama Desk Awards, UNIMA Awards, Bessie Awards, a New York Innovative Theatre Award, a Henry Hewes Award, Guggenheim and USA Artist Fellowships, and the Doris Duke Performing Artist Award. He has taught and lectured at universities including Princeton and Stanford and on behalf of the U.S. State Department.

One would assume such a legend rarely has time for reporters, but Twist proved eager to speak with me, to wax poetic about his time as an intern for the Center in the ’90s. Twist called from Rome, Italy, where he lives and works at the American Academy.

“The Center let me see that I could connect to the world of puppetry — not just be a puppeteer here or there,” Twist told me. “I was making coffee for the puppeteers and sweeping the little, tiny puppet stage with a little, tiny broom. I worked with Peter Hart and Jon Ludwig. I was really in awe — and still am — of Jon Ludwig.”

Jon Ludwig, Artistic Director

The internship program has evolved over the years into a much more collaborative and immersive process, catered to the interest of the intern at hand. One thing remains, though: Ludwig’s passion and gift for recognizing talent in potential puppeteers and fostering it.

“That man is a genius,” exclaims Lucky Yates during our phone interview.

“I love watching Jon audition people, it’s like watching a mini master class for every person,” reflects Kristin Haverty, a producer at the Center. “He takes the time with each person, showing them how to breathe with the puppet, to move with the puppet.”

Ludwig sums his approach up this way: “Usually, you can tell who has potential by the amount of fun that they have. They have a good spirit to them. You’re playing a doll, an inanimate object, so you can’t take it terribly seriously.”

Ludwig humbly attributes his career’s origins to having his driver’s license. After taking a puppeteering class in college, he spotted an ad in the paper.

“It said, ‘Puppeteer wanted. Will train.’ And I got hired! Mainly because I could drive the van.” He took to the road with the touring production of “Pinocchio” with Vagabond Marionettes, a touring company the Center once operated.

Today, Ludwig works with his motley crew of performers, set designers, stage managers, puppet builders, and artists to continue Vincent Anthony’s vision for the Center. They have breathed life into a wide span of stories over the years, everything from Frankenstein to Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer; from Winnie the Pooh to The Illuminating Adventures of Red Rocket in Space. Their interpretation of Pete the Cat brought the series’ author, James Dean, to tears. Yates lovingly recounted one melodrama, “Avanti! DaVinci!,” which depicted Leonardo DaVinci as a Batman-esque defender of justice against the evil Borgia family — an original play developed and written by Ludwig himself.

“It’s all about collaboration. That’s what’s important,” says Jason Hines, a puppet designer at the Center. “Above and beyond all other types of theater, you have to be able to collaborate to make it work. The things that are rewarding are when people come up with a crazy idea, and then we get to see it come to life. It’s all about constant experimentation.”

The office of Jason Hines, Puppet Designer and Builder, is a kaleidoscopic collection of tools, thread, latex, and fleece.

Since its humble beginnings in the former schoolhouse, the Center has made a name for itself for its capability to blend old-world techniques with contemporary technology, broadening the possibilities for the puppet stage.

“At the Center, there’s always an expanse of ways to tell the story. In theater, you have the restrictions of a live actor. But a puppet can grow in size, character, and change form,” says Gregory Montague, the Center’s production manager. “The expanse of what you can do gives you a wide range of the stories you can tell and how you can tell it.”

Their anything-is-possible mantra laid the groundwork for one of the Center’s longest-running programs: XPT — Experimental Puppetry Theatre. The grant-based, annual program allows a broad array of puppetry talent to take an idea and run with it, awarding small grants to develop the idea and then perform it on-stage during the Center’s XPT festival every March.

“A lot of it is exploring new ways of defining what a puppet can be. It’s not always mechanisms and techniques,” says Hines. “Is yeast making a loaf of bread rise puppetry? We had one XPT that was an opera about rising and breathing.”

For veterans of the XPT program like Raymond Carr and Kristin Haverty, the chance to experiment is worth its weight in gold.

“It blew my mind,” Carr says. “Before my first XPT, I had mostly done puppeteering within the church. Seeing avant-garde experimental works for adults blew my mind. It was what I had always wanted to do. It embraced me.”

Raymond Carr

Since his first XPT (which he completed just after his 18th birthday), Carr has either directed or participated in a dozen XPTs. After participating in a few shows and different XPTs, the Center introduced Carr to career opportunities in the field.

“Through the Center, I was able to travel to Iceland, where I worked for a year on a show for Nickelodeon,” he says. “They introduced me to a bunch of artists from that world. They connected me with Heather Henson, Jim Henson’s youngest daughter.” Her company, Ibex Puppetry, went on to award Carr a $10,000 commission to produce his original work “Hitori,” now screened all over the world and distributed by The Henson Company.

Kristin Haverty

Haverty participated in her first XPT after touring with the Oregon-based Tears of Joy Theatre for a year. Her experience with XPT led her to quit the road life and begin working as a Teaching Artist in the Center’s Education Department, working at the Center’s Museum store, and as a docent.

“We’ve had people that have gone on to develop their XPT shows into larger shows,” she says. “Andy Gaukel did a 10-minute XPT. He developed that piece and has gone on to do residencies at the Institut International de la Marionnette in Charleville-Mézières, France, develop a show in Montreal, and now has toured to many locations and taken that show everywhere.” The XPT program has supported the local community as well — working with young artists from Georgia State University, Kennesaw State University, Georgia Tech, and SCAD. “Great collectives and partnerships have arisen from those XPT relationships,” she says.

The programs the Center produces to support burgeoning talent — guest performances from acclaimed puppeteers, educational programs, internships, and XPT among them — are major forces keeping the art form alive and thriving.

“The great thing about the Center is that they really want artists to thrive and to maintain a connection with them,” Carr says. “They are very generous about promoting individuals. There’s still a very large contingent of performers from coast to coast who have spent time at the Center for various shows. It’s a worldwide hub.”

For Twist, whose star has risen so high, the time he spent at the Center was crucial to his development as an artist. “It was really about being more connected to the world and becoming plugged in,” says Twist. “The Center was key to that for me and remains that way. My early days there were very useful. It showed me the world.”