Here’s a scene.

“Play ‘Tequila,’” the patron says. “Play it one more time.”

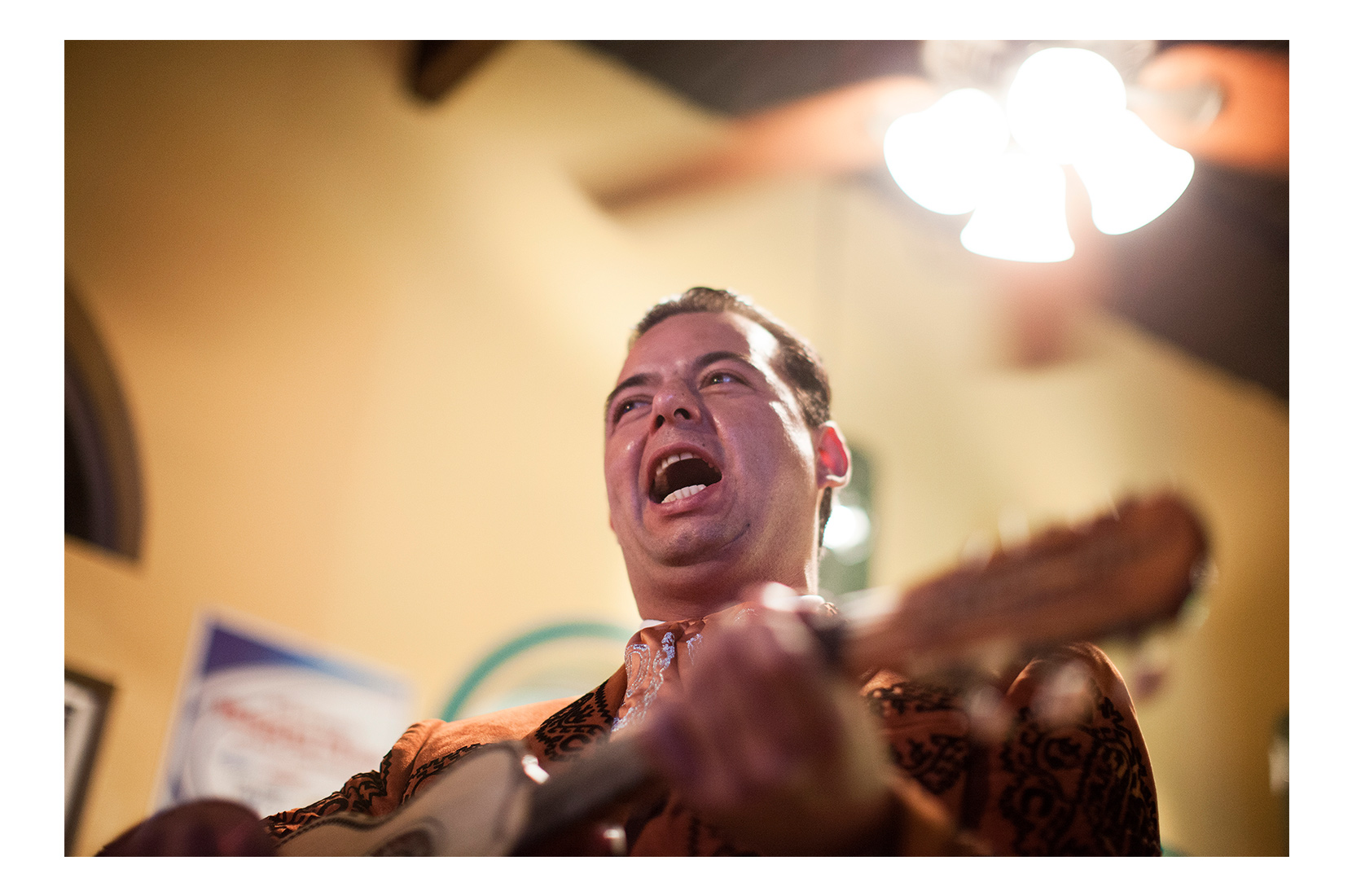

Luis Vazquez and his Mariachi Mexicanisimo band mates politely nod and dive into the only reason anyone on this planet knows the Champs, a band that earwormed its way into American culture with this Chicano-tinged surf-rock song in 1958.

Thankfully no one in the restaurant can recall the sequel, “Too Much Tequila.”

In Two Places at One Time

East of Atlanta in an unassuming strip mall a short jog away from I-20 sits Monterrey’s Mexican Restaurant

The sign above the door reads, “Welcome Amigos.”

Inside, it’s a busy night, a Friday maybe. Mounted flat screens are tuned to the night’s Liga MX match and whatever college football game ESPN may be replaying. Orange and teal paint lines the archways and support beams. Murals capture pastoral scenes of Mexico. A variety of tequilas and mezcals proudly towers behind the bar. Depending on the time of year, the local high school teams’ posters will be displayed near the front door, the Lithia Springs Lions, the Douglas County Tigers. The patrons fill booths and four-tops, a large party pulls multiple tables together. Margaritas, chip baskets and ramekins of salsa cover nearly every single placemat in the house.

“Tequila!” the patrons scream as Luis and his band strike the last chord. The room claps, a few people whistle. The restaurant is full and happy. The band takes a beat. Then feeling the momentum in the room, Humberto, the violinist, kicks off an inspired cover of “The Devil Went Down to Georgia.”

This is a typical night in a typical restaurant for Mariachi Mexicanisimo, a Georgia-based mariachi band led by viheulist (and second vocalist) Luis Vazquez. Rounding out the group is Jose Lara on guitarron, Humberto Perez on violin and lead vocals, and Octavio Garcia, who plays the trumpet.

Vazquez and his band are one of 30 or so mariachi bands in the state of Georgia. They primarily gig in restaurants like Monterrey’s, playing for gringos on a night out in places like Douglasville, Jonesboro, Marietta and Smyrna, the suburbs and exurbs that echo out from the center of Atlanta.

Mariachi Mexicanisimo play traditionals, like “Sabor A Mi,” and cover pop songs like Michael Jackson’s “Beat It.” They wear traditional mariachi suits — trajes — while patrons dine in shorts and hats. They harmonize, beautifully, while the kitchens clamor and phones ring in the background. Loosely translated, the name of their band means mariachi very, very Mexican. What is equally true, though, is that they are also very much American.

This is a band in two places at one time.

The Shifting South

This duality drew photographer Gregory Miller, who grew up in Roswell, Ga., to follow the band and document their work.

“My impressions on mariachi were formed in my early teens when Mexican restaurants began popping up in my hometown,” says Miller. “I ate the pork burritos, chips and salsa while tolerating the roaming entertainers who worked a gimmick and lived, incorrectly I assumed, off tips.

“As I’ve gotten older, I’ve grown more curious about the cultural shifts going on around me. In a lot of tangible ways, Georgia is a very different place from when I was a kid.”

This is not just Miller’s observation; it’s fact. The 2010 Census revealed that U.S. residents identifying as Hispanic rose 43 percent since 2000. This accounted for 56 percent of the nation’s total population growth. The states that represented the fastest growth? Almost all were in the South. According to Pew Research’s Hispanic Trends Project, Georgia’s Hispanic population grew by 96 percent over the past decade. Three of the 10 fastest growing counties by Hispanic population are located in Georgia. And Georgia’s neighbor to the west, Alabama, has seen its Hispanic population explode 158 percent in the past decade, more than any other state in the country.

The face of the South is clearly changing.

Vazquez represents the changing face of the South, if not all of America, but his story is slightly different from those who have crossed the border in search of a better life.

To Be an Artist

While mariachi music clearly incorporates European and African influences, it’s largely understood to have been invented in the state of Jalisco. It officially arrived in Mexico City early in the 20th century when a band was hired to play a party for, depending on which story you believe, the newly elected president of Mexico or an official visit by the U.S. secretary of state. From there, the mariachi scene took root in Plaza Garibaldi, where Vazquez’s father, godfather and uncle were among the earliest performers playing at all hours of the day.

Vazquez’s father went on to tour with a number of accomplished mariachi bands in Mexico and Spain, until he eventually moved with his family to the United States. Growing up in Georgia, Luis Vazquez spent most of his youth tagging along with his father from restaurant to restaurant, listening to the band perform for largely white audiences in the South. It was this experience that inspired him to follow in his father’s footsteps.

“I would drive with my dad to the restaurants,” Vazquez says. “Just being with him, not playing, just looking at the way people reacted. I heard the clapping. It made me want to be an artist.”

The traditional mariachi band consists of up to eight violins, two trumpets, a guitar, a vihuela (the key to mariachi’s unique rhythm), a guitarron (or acoustic bass) and a Mexican harp. Vazquez learned to play the guitar, then the vihuela, mostly by ear and years of tedious practice until he became competent enough to join his father’s band. After turning 18, Vazquez, like anyone his age, broke with family tradition. While still intensely proud of traditional mariachi, Luis wanted to expand beyond patriotic and mournful ballads. He wanted to incorporate mainstream popular songs his audiences could identify with.

“Mexican people like to put lime on a cut,” Luis says. “When our hearts break, when we are sad, we like to hear songs that make us cry. I enjoy the mariachi music because I feel it. But I like the challenge of playing American music, too.”

Today, the Mariachi Mexicanisimo playlist incorporates the Eagles, Jimmy Buffett, Michael Jackson and Lady Gaga, to name a few. They often take requests, quickly transforming a radio hit into a mariachi classic. The band even once learned the Scorpions’ “Rock You Like a Hurricane” for a patron’s birthday party. The idea, Vazquez explains, is not to sell out, but to break down barriers, to give audiences the familiar so they can enjoy the strange.

“Mexican people like to put lime on a cut,” Luis says. “When our hearts break, when we are sad, we like to hear songs that make us cry. I enjoy the mariachi music because I feel it. But I like the challenge of playing American music, too.”

No More “Tequila”

“Since I began this project, I’ve experienced something of a transfer of annoyance from the mariachi to the audience,” Miller says. “‘Tequila’ and ‘Feliz Navidad,’ no matter what season, those songs should be retired. The songs I love are the traditional tunes. I don’t understand the words, but I ask the meaning and listen to the way they're sung. Even if you don’t understand Spanish, you come away with an impression of the meaning.”

A flattering comment, for sure, but few patrons listen to mariachi with the same studied intent as Gregory Miller. It’s not uncommon for diners to ignore the band or shake their heads as the band slowly walks up to a table. Sensitive to this situation, Vazquez understands that not everyone is won over on the same night. Change takes time.

“It’s more conservative in the South,” Vazquez says. “But they’re becoming more open-minded and we’re adapting, too. We play country music now. We play Johnny Cash.”

Though James Brown, another Georgia native, often claimed the title, Vazquez and his band make a strong argument for being the hardest working men in show business, playing seven nights a week most of the year.

There may be no greater evidence of this work ethic than the band's YouTube channel. Loaded with performances at Monterrey’s and other area restaurants, viewers can see the band playing for diners, inviting them to sing along, to get up and dance. They play hits. They play classics. They even play churches, participating in the celebration of the feast day of Our Lady of Guadalupe, arguably the most important day of the year for Mexican and Latino Catholics around the world.

As the last diners leave and the waiters begin organizing their checks and the bartenders begin to clean, Mariachi Mexicanisimo perform one last set at Monterrey’s.

Luis and his band mates make their way toward the back of the restaurant, past the waiter’s station and into the kitchen, where they huddle in a corner and turn their instruments on the staff. No pop songs are played. No Christmas carols sung. The band simply dives into a traditional. Immediately, the staff stops their closing duties and after a few chords one of the cooks steps forward and hits his mark, singing full and proud, as if he’d been waiting all night for his turn.

Home Is Always With You

This is a tradition for Luis, the chance to offer a few songs that remind the rest of them, those others from other places who work the room and the stoves and the sinks and the trash that their home is not far, but always with them.

The integration of cultures is so often thought of as a clash: the outsider invading a native land, either conquering the indigenous or bowing to assimilation.

The truth is tradition and culture sustain themselves not through purity and absolute preservation, but through introduction and acceptance.

For Mariachi Mexicanisimo, this means offering a song to a table, and for the table it means pausing long enough to enjoy the performance.

It means taking a request and playing a song the whole world recognizes in order to perform in a language few people understand.

It means that if we listen closely and pay attention, we’ll see that all of us, not just Luis and his band mates, are in two places at once, too.

“The truth is tradition and culture sustain themselves not through purity and absolute preservation, but through introduction and acceptance.”

Photography & Video by Gregory Miller. Words by Peter Short. Juliet D'Ambrosio conducted the interview with Luis. Dana Simmons captured all location and interview audio sessions. Daniel Hollister assisted on all photo/video shoots.

Through the Lens:

A Q&A with Gregory Miller

Gregory Miller is one of the South’s top photographers. His images have graced the pages of Esquire, Dwell and Southern Living magazines, among many others. Here, Peter Short interviews Miller about how he became fascinated with Southern mariachi bands.

Meet the Band: Mariachi Mexicanisimo

Check out our handy guide, so you'll always know the answer to the question, "Dude, do you remember who played vihuela for Mariachi Mexicanisimo?"

Next Week:

All Wealth Is From the Earth

Alex Matisse says he came to Marshall, N.C., to “find myself in some way, and go into learning a traditional way of making.” In the years since he planted himself in this small town north of Asheville, he first immersed himself in a long apprenticeship to a local potter, then he built his own operation, East Fork Pottery, which produces work that literally shifts with the four native elements: Earth, Air, Fire and Water.

The Bitter Southerner©2013 All rights reserved.

To contact The Bitter Southerner for any reason at all, you can connect with us through Facebook.