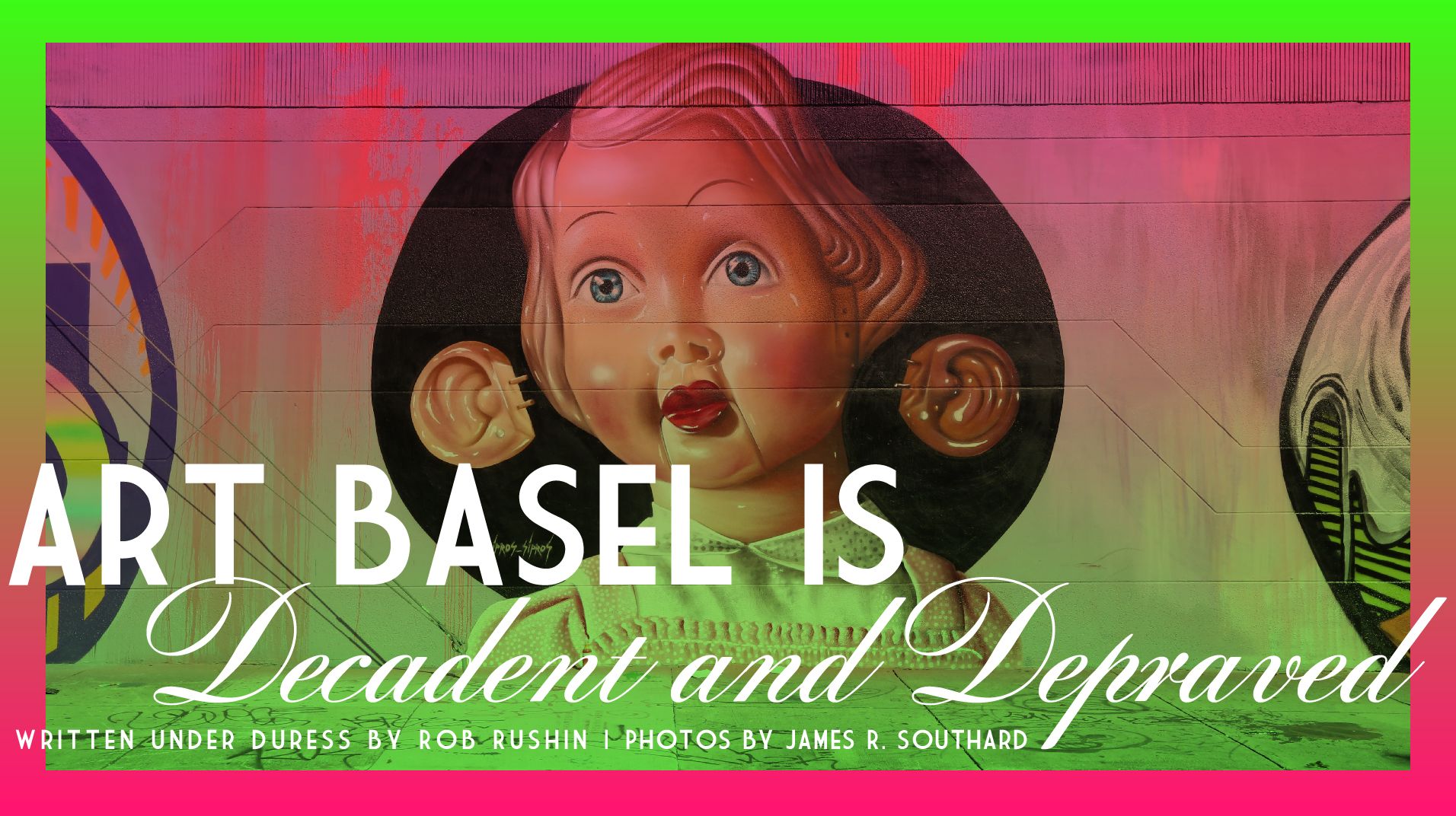

Happens every year. Like clockwork. The world’s richest art aficionados come to Art Basel in Miami Beach. We wanted to send an outsider down there — somebody who could mix it up with the Swells in the name of truth and entertainment. The great Kentuckian Hunter S. Thompson is 12 years dead now, but we found a guy almost as crazy — and still alive. We figured we could trust him — but only if his sidekick, Stanwyck, tagged along. This is their story. They found decadence aplenty. Oddly enough, they found some Art That Matters, too.

Written Under Duress by Rob Rushin | Photographs by James R. Southard

I was blowing smoke at a stack of unpaid bills. Just a little more wind and they would meet the ember, all my problems gone. Up in smoke. Easy. Poof.

Right. And I’ll be spending the weekend with Scarlett Johansson at St. Kitts.

The only thing louder than the drumbeat of raindrops on my desk was my landlord pounding the office door, demanding rent. I was down to smoking stub-ends cadged from the Doe See Doe, where my bar tab sat “closed until further notice.” Dumpster-diving behind the pot dispensary was a grim version of the Hunger Games. I was getting too old for that kind of savagery. My stomach grumbled, and my hands shook. Something had to happen. And fast.

The telephone made me jump. Hunger makes a man tight, on edge. I tried to ignore the call, but even a writer has a conscience. Sometimes.

It was The Editor.

“Narrator, damn you,” he barked. “I’ve got a story, and I want to know if it’s your kind of thing. I’ve called 20 other writers, but everybody is busy.”

My kind of thing? I would have gladly endured a bikini waxing and turned 3,000 words about how enlivening it was. A tour with Bieber. Anything.

“Maybe,” I said, cagey. “I’m busy as a one-armed paper hanger with the hives and...”

The Editor barked a laugh that I felt was, well, ungenerous.

“Can the con. You were scrounging ashtrays just last night. Here’s the pitch, see. Miami Beach, no place farther south. Dig up a story about the whole Duality of the Southern Thing …”

Oh, jaybus. That rigmarole again. My head pounded from the bottle of aftershave I drank for breakfast.

“…and there’s some hoity-toity art market thing happening, all swells and celebs. Art Basel, like that city in Switzerland. You gotta work that in. You know anything about contemporary art?”

Me? I don’t know a Picasso from a pickaxe, a Koons from a coon dog. But Bitter Southerner pays big bucks with an expense account to match. I’d cop some ether, drink on the Editor’s dime, and score a fat payday. A cinch. Ring-a-ding-ding.

“Sure thing. I studied Art History at reform school. But I’m gonna need a research assistant.”

“Money is no object — but only if it’s Stanwyck. I trust her, not you. And keep it simple, hear? None of that wordy, deep-meaning crap. And dammit, no trouble like in St. Kitts. Scarlett’s people are still pissed and…”

Click. Like I needed a reminder of that debacle. Besides, I had some crawling and groveling to do with Stanwyck. Lucky for me, she doesn’t hold a grudge.

She’s the perfect wing woman, that Stanwyck, a wisecracking dame who knows her way around a museum, knows which end of the paintbrush means business, and mixes a mean cocktail. Tough as nails, she can down martinis and bourbon shots two-to-your-one, and she’s handy with a sap if things get ugly. She can sort out the fine-art interpretive nonsense while Your Narrator gets down to the nitty-gritty: When does the bar open?

I thought we were prepared. In retrospect, my failure to secure an advance supply of ether was a harbinger of bad mojo to come. Ibogaine will take you only so far. And Stanwyck turned out to be not much for sharing. Damn her.

The art world is a treacherous place. Only the strong survive.

Wheel south on Interstate 75, down the core of central Florida, and there is no doubt about where you are. This is the rural South, pal, no mistake. But there comes a point where the Southiness dwindles, and you find yourself in some other realm altogether. Right around the time you merge onto Florida’s Turnpike — just west of The Villages, an hour or so northwest of Orlando — something shifts. The farther south you travel, the less South it feels.

Yes, Bitter Southerners: Join us as we travel beyond the Duality of the Southern Thing (DST) into some sort of multidimensional labyrinth that both envelops and transcends standard-issue Southiness. Common wisdom claims anyplace south of a line from Palm Beach on the Atlantic to Fort Myers on the Gulf is not the South. Our transit suggests the Island of Orlando is pretty much the fading edge of the DST, a place where the familiar rhythms and smells of the South begin to take on the vibes of someplace else.

Exhibit No. 1: You cannot get iced tea at any of the Turnpike’s refreshment stops.

But as we left the DST behind, our spirits lifted at the prospect of ocean air, palm trees, umbrella-laden drinks, the promise of ether. In the distance, a gleaming skyline, a stylish blend of shimmering glass and steel and forests of high-rise cranes: Miami.

We were on a mission, a Quest with a capital Q. We were in search of Art.

Besides, Stanwyck was getting thirsty.

Big lights, bright city: currently under construction.

A supposedly fun thing somebody really should write about someday

First thing: Miami Beach is gorgeous, as long as you gaze Africa-way. But like our evolutionary ancestors, eventually we turn from the water and head to higher ground. As our forebears found, what awaits is by turns charming and horrific. On the one hand, Miami Beach boasts the greatest concentration of Art Deco architecture in the world. On the other, Miami Beach seems to boast the harshest concentration of vehicles in the world.

On still another hand, this is a place to ogle, no matter which way(s) you swing. The cult of the perfect body is one of the primary drivers of Miami Beach ambiance. Miami Beach is a place that takes clothing seriously.

In one fashion camp, ultra-expensive tailored suits and dresses, ultra-sharp stilettos for the women, and $2,000 calfskin loafers for the men. On a casual day, T-shirts and distressed jeans pegged at $250 per provide the kind of calculated sloppiness that mere mortals cannot afford.

Members of the other Miami fashion camp wear form-fitting creations engineered to emphasize pectoral profiles and gluteal curvature with keen attention to maximal skin exposure. And that’s just the guys. There is no more intensely devoted cult of well-oiled muscle anywhere.

Miami Beach has always been a Latin-tinged love child of the Vegas Strip and Bourbon Street, a destination for tourists determined to have spontaneous fun in a predetermined way. The weather is gorgeous year-round, with the freshest ocean air you’ve ever smelled, as long as your idea of fresh includes cigars, perfume, sunscreen, and the stickiest ganja north of Montego Bay. Annually, around 4.5 million tourists arrive to cram this tiny, man-made island — most, it seems, during Art Week. Miami Beach proper covers approximately 18 square miles, but 11 of that is water. It is cozy.

It also boasts the finest conglomeration of Art Deco architecture in the world, an endless string of renovated hotels and restaurants to conjure visions of Don Ameche sipping a cocktail while waiting for Gene Tierney to sashay along — if you can somehow ignore the perpetual thumping of over-amped sound systems and seizure-triggering light displays. Despite these depressingly common signifiers of event attendees having a really good time — no really, this is awesome — there is some undeniably magical nostalgia at play.

But sweet Jesus running late to the temple: the traffic. If you’ve seen New York’s Fifth Avenue the weekend before Christmas, or New Orleans on Fat Tuesday, you get the picture. Cross-island streets sit at semi-permanent standstill, intersections in perpetual gridlock. There was literally no destination we could not reach faster by foot, so we logged around 13 miles a day. All for you, dear reader. All for you.

Late one afternoon, our dogs were barking, and I was a little, um, compromised. Stanwyck hailed a cab and shoveled me in just ahead of collapse. Our driver was from Cairo, and not the one in South Georgia. He spent the entire trip hurling unholy oaths at his fellow motorists.

“Traffic here is worse than Cairo.” Spits out the window. Turns out his command of English is impeccable.

“SONOFAGOATSHITTING WHORE, I BREAK YOUR FUCKING...”

And so it went, for 40 minutes.

“So sorry, madam, for the language, but these damn Cubans, they come here and don’t know….”

Stanwyck said quietly, “I am Cuban.” She is not, but she detests stereotypes.

“Deepest apologies, madam, I mean no offense, simply {{{{screeeeeeech}}}…MAY FATE TEAR OFF YOUR HEAD AND PISS DOWN YOUR NECK, YOU…. Here we are at last, then, have a nice day.”

That was when we realized that we had traveled all of half a mile at a cost of $11. I sat down hard on the sidewalk. Stanwyck doubled over in laughter. I was certain she was hiding some ether in her purse. I wondered what happened to my shoes until I realized I was still wearing them. The ibogaine was working.

Stanwyck wouldn’t give up. There’s Art here, she said, something that would take her breath away.

“Like Clooney?” That night in Kigali. The wound still stings.

“Buck up and quit feeling sorry for yourself. We got work to do.”

Dragging me along like a sick cur with three legs, Stanwyck set forth to find Art at Art Week. When our taxi dumped us on the sidewalk, we were in front of the Miami Beach Visitors and Convention Center, home to the 15th Annual Art Basel Miami Beach (ABMB) extravaganza. It is a charmless cavern built for trade shows — think plumbing supplies or consumer electronics— with thousands of anxious vendors wedged butts-to-nuts, everybody hungry to make that sale.

This is the core of Art Week. A 15-year-old younger sibling to the original Swiss fair, ABMB covers around a million square feet, featuring 259 galleries, 4,000-plus artists, and countless paintings, sculptures, installations, photographs, films, videos, and digital art. It is yoooooge and pretty much unbearable to an unmedicated nervous system.

You couldn’t see everything in four days. Don’t even try. We made it to 11 exhibitions. That means we missed at least twice that much, not even counting the various parties, raves, and celebrity galas from which we were inexplicably excluded. Well, not Stanwyck. She got in everywhere. Damn her.

Art Week is about many things, most only tangentially related to art itself. Money. Fashion. Celebrity. The Deal. These are the real features of Art Week. Yachts. Private jets. Rolls-Royce limousines. Lamborghinis and Vipers and Ferraris. Celebs pretending not to pose for paparazzi. Central casting runs amok, pushing clichés to the breaking point. Art serves as the place setting, the table for the feast. Everything is just fucking fabulous.

It’s easy to get jaded and cynical and, well, just overwhelmed by the sheer vastness of the affair and by the promotion-obsessed hustlers who bum-rush anyone with a press pass. (This is an especially gruesome form of incubi/succubi. Abandon all hope if one gets you by the arm.)

It’s easy to take potshots at the contemporary art scene, especially the galling one-percentishness of the thing. It’s easy to laugh at the absurdist playlet of eager gallerists bouncing up and down step stools to rearrange Damien Hirst’s glorified mall-art butterflies for a potential buyer. A bored-looking couple sighed sadly that it “just won’t go with the Fritz Hansen.” No sale. They moved on to ponder the compatibility of their décor with a Mister Brainwash piece.

It’s hard to remember there is — or at least should be — something more to Art Basel. But the footsore pilgrim gets to the point where she says, “Oh, look, more Calder,” nonplussed as Picassos and Miros glide by, just another commodity. Just look at all the damn Motherwells. The sensory overload is beyond human tolerance; by the last day, even the gallerists wore a haunted, abandoned look that fairly begged for euthanistic relief.

But what about Art as a force for social change? Surely, faced with the specter of a President Trump, the notoriously liberal Art World has mounted the barricades. Inspiration must be at hand, a Guernica for our times! Vindication!

What we found was not encouraging.

One of the most hyped “political” works came from artist Rirkrit Tiravanija, bearing the phrase “THE TYRANNY OF COMMON SENSE HAS REACHED ITS FINAL STAGE.” Printed over pages from the post-election day New York Times, this seems a fairly tame spitball at power, especially when we consider that, after selling for $90,000, the piece will hang safely away from anyone who might be inflamed by the sentiment.

Likewise “Landscape Art Sign (Emory Douglas),” a 2003 light-box painting by Sam Durant. Black type on a glowing red background declares that “LANDSCAPE ART IS GOOD ONLY WHEN IT SHOWS THE OPPRESSOR HANGING FROM A TREE BY HIS MOTHERF**ING NECK.” As inflammatory rhetoric, this quote from Black Panther Minister of Culture Emory Douglas is a real corker, but try to imagine a more effective neutering of its incantatory potential than a $75,000 price tag.

Other provocations included soda cans giving us the finger and a latex bust of a President-elect Donald Trump drowning under a pile of envelopes. Nobody in Trump Tower is hiding under a desk over this. And Jack Pierson’s “Capitalist Decadence” — priced at a cool quarter-mil — is another in a long line of arch ironies, examples of anti-capitalist art richly rewarded by the capitalists themselves. An artistic ouroboros, a snake eating its own tail.

The possibility that Art-with-a-capital-A might somehow be a vapid, narcissistic self-indulgence screams out loud in this environment. With everything crammed in like a bric-a-brac thrift store — frantic juxtapositions of styles and artists, no room to stand back and look — it’s easy to just throw up your hands and head back to the bar. Face it, bub. Your Goddess of Art has feet of clay, and, in this circus, they’ve been painted with a coat of glitter, a pithy headline pasted across them to make a statement. And don’t ask how much; you can’t afford it.

But there has to be a reason for being here other than fleecing The Editor. Art matters. Or at least it should. Lesser mortals quail in the face of the grotesque, jittery energy of people on the make, the preposterous lengths that artists and galleries go to in vain attempts to shock, thrill, titillate.

Not Stanwyck.

Want to see how the .01 percent live? Visit Miami Beach and step into one of the classic hotels: The Raleigh, The Fontainebleau, The Delano. Recalling the heyday of Art Deco luxury, these joints offer weary wanderers a choice between resting on a gold-encrusted, Dali-designed chair or an oversized Philippe Starck sofa. Maybe you’d rather rather trinkle your diamond earrings around the transparent Lucite piano under the soaring lobby ceiling? We opted for a cozy bar, all deep-grained wood and twinkling light, the rows of bottles reflecting into eternity in the mirror behind the bar.

Stanwyck ordered a $34 martini. Sweet mercy, the tastes of this woman. I ordered a beer and a shot of cheap Irish to calm my nerves. We settled in to watch the crème de la creamy crème in their native habitat. I haven’t seen a floor show this fine since that double bill of the two Joeys — Bishop and Heatherton — at the Sands. It was me and Joey No Socks and some fat schmuck from Queens named Don, and…

Never mind.

A very expensive haircut in a suit that cost more than my car took an extra-fussy long time sniffing and sipping wine samples before deciding on his red of choice. A quick look at the wine list revealed the cheapest red rang in at $38 a glass; let’s assume this gent didn’t settle low. As he savored his luxury pour, he deployed a classic pinky-twist maneuver to unplug his right nostril, and, well, let’s just say he must have been hungry and leave it at that. Draining his wine in a flourish, he left, presumably in search of more substantial fare.

The rich are different from you and me. Or not. For what it’s worth, that was the first time I’d ever seen Stanwyck shudder.

Our bartender, sizing us up as slummers who didn’t belong in such a fancy joint, warned us to beware the sly Miami Beach practice of tacking a 20 percent gratuity onto your check and leaving a blank space for another tip. After 24 hours of being suckered, we tipped him a couple of Hamiltons in thanks. He gave us another round on the house, so we hung around, luxuriating in our rare admission to high society, marveling at the lifestyles of the rich and famous.

Just down the bar sat the poster girls of Cosmetic Improvement and Enhancement. These spray-tanned, identical twins had perfectly ironed golden hair, matching white designer jeans and tank tops, and identically engineered bosoms held aloft in impossible feats of cantilevered gravity defiance. Their lips were plumped in perfect harmony to one another, swelling like identical sets of tumescent chrysalides just before the butterfly spreads its wings. Their gestures were exquisitely refined — the backwards toss of the head, the perfectly capped teeth glinting through perfectly modulated laughter, the careless flick of the wrist, the palsied, twisted smile that only a well-botoxed rictus can sculpt. They ordered a series of neon-tinis (these things made Stanwyck palpably angry) and played out their little scene whenever a well-turned male was nearby, saving energy when there were none.

Even though one spoke with a Latina accent and the other was a daughter of the South, you had to hand it to them: The branding was impressive.

Stanwyck said it was time to move on, and I was in no shape to argue. We headed south (!) to mingle with the less nobby crowd, maybe find something to help fill in the blanks of this crazy story.

We found ourselves wandering afield from the swells and into a residential neighborhood, a little down at the heels, but lovely and warm and cozy. We heard not one word of English for about 40 minutes. We passed open windows of communal laundry rooms, gaggles of laughing women ringing into the night. In Flamingo Park, there were baseball games — from Little League to adults — with coaches exhorting and kids yelling and laughing. There were a dozen soccer fields. There was an open window at ground level, a tired looking woman slumped in front of a TV in her nightgown. There were dogs barking and babies crying.

There was real life.

One wonders what the locals think of the glitz invasion. Do they feel gratitude at the influx of heavy spending? Aggravation at the disruption and disrespect? Some combination? The people we asked offered only that it was a week of good tips and terrible traffic.

The art? Beside the point, it seemed.

"No matter how cynical you become, it's never enough to keep up."

— Lily Tomlin

With our cynicism failing to keep pace, we tried on a strategy of belief. There just had to be some there, here. The sheer volume of work from around the world meant that, even if only by accident, there must be. There must. We believed.

We searched earnestly for a glimmer of the thing that makes Art something other than a scoring mechanism for the one percent. Like Charlie Brown and his sad little tree, we were not going to let rampaging commerce and cynicism have the last word.

We started start outdoors in the Wynwood Arts District. Once known as Miami’s Little San Juan, Wynwood is a working-class neighborhood of Puerto Rican and other Latino cultures, a sweet little cluster of businesses, warehouses, and modest homes that fell on hard times in the 1970s and ’80s. It provided cheap space for an influx of artists and musicians to live and congregate and has since been re-branded as an arts district, with dozens of galleries, museums, and collections. It also encompasses the Miami Fashion District. How much fabulousness do you want? Of course, Wynwood Walls became a destination, and alas, Wynwood becomes another in a long line of gentrification targets. It retains its character. For now.

If you get a chance to visit, go spend a day in Wynwood. The murals are stunning. The Rubell and Marguiles are exceptional private collections. The food and bar scene is crackling, and the people are friendly. You find little cynicism and no jaded glances down the length of a well-sculpted nose. It’s a place where honest and earnest creativity comes to play. And the quality is world-class.

We visited a mural-in-progress on NW 27th Street, our host a fiery blast of energy named Chiara Saldivar McCluskey. For the past four years, her Wynwood Embassy organization has hosted international artists for Miami Art Week to transform one after another expanse of brick and cinder-block into eye-popping art. This year, Italian street artist ZED1 was at work on the front of a building while Chiara’s husband Danny prepped the side wall with a roller and a bucket. This was hard, physical toil. There was a long, long way to go, but the image was starting to take form.

PHOTOS Courtesy of Wynwood Embassy

The sense of excitement, the thrill of creating: This is what we’d been missing, because the most under-represented segment of the art world at Art Week is, sadly, artists themselves. Where the deal is paramount, the artist is an awkward impediment. But here, with no deal in the offing, it’s just artists, making. Wynwood Embassy is essentially two people working multiple jobs to make something beautiful happen. It’s a reminder of the labor that goes into art, the passion and sweat and desire that the whole pyramid of Art Week commerce and hype rests upon. The value creators do the work; the rentiers reap the rewards. It’s a lesson as old as money. But the art remains. Beautiful.

A short walk away, the Rubell Collection showcases one of the largest private collections in the country. The ground floor of this former DEA warehouse was given over to “New Shamans,” an exhibition of recent works by emerging and mid-career artists from Brazil. Upstairs we found “High Anxiety,” an assortment of works acquired since 2014. Together, these works offered a welcome counterpoint to the Art Week fairs. Again, here was art removed from the stream of commerce. Here, we had room to breathe, to stand back and linger.

We found Stanwyck upstairs, breathless, glued to a video by Hito Steyrl. There was no pulling her away until the end.

These are the moments that make Art Week worth the effort. Stanwyck even held my hand. Briefly.

Take that, Clooney.

Later that night we caught the Satellite Art Show in the Parisian Hotel on Collins Avenue. It’s a classically grungy Florida dump that, given the realities of real-estate valuation, can’t be more than a year or two from tear-down. Until that sad day, Satellite offers a down-to-earth ethos, heavy on the DIY, with none of the Art Basel glitz. Scruffy and, we thought, admirably anti-professional, there was real warmth and charm at play here. Every room had been prepared for Art Week, with clever and intentional choices of lighting, wall and ceiling treatments, furnishings, and in some rooms, temporary flooring.

Molly Krause/Molly Krause Communications

On the night we visited, The Parisian was also hosting a concert in the lobby. Both events were mobbed. The air was thick with high-grade smoke. Stanwyck took one look at the narrow stairs and the size of the crowd, deemed it a fire trap, and went to wait outside. Probably an ether ploy. Damn her.

I was on the second floor when I noticed a room — belonging to The Southern Contemporary Gallery of Charleston — papered with the exact same toile that had graced our dear old Gran’s living room way back when. Charming renderings of the Old South in delicate shades of grey and ochre. Who could resist this touch of Southern charm?

Courtesy of the artist and The Southern Gallery

Notice the landscapes of Civil War battlefields, mixed-media collages, portraits of battle re-enactors — one white, one African-American. Closer inspection reveals the charming wallpaper vignettes to be, well, more bitter than charming. The scenes depict the cycle of slavery — acquisition, sale, discipline, domestication, and revolt — that underlies the prosaic memories of the Lost Cause, the “white-washed, romanticized re-branding of plantations in the American South,” as their creator, Charleston artist Colin Quashie, puts it. Duality, baby. This ain’t your grandma’s toile. Bitter Charlestonians are encouraged to visit The Southern and pick up a few rolls of Quashie’s wallpaper for your next renovation. Do it for your Gran.

About that time, the fire marshal bum-rushed the Parisian and tossed everyone — art lovers and music lovers alike — into the street. Probably a good thing: It was so smoky in there, we never would have noticed the place ablaze until well too late.

We awoke next day to news of the fatal warehouse fire in Oakland. The circumstances were not all that different. Art can be dangerous.

When I got outside, Stanwyck was gone. To another party.

With Clooney.

Damn her.

Want to be heard? Speak quietly in a noisy room. Whisper when others are shouting.

The next day we visited “Untitled Art Fair,” one of the la-dee-da, beach-based tent affairs. This was no ordinary tent: a half-dozen full bars, several gourmet food vendors, all bathed in sumptuous sunlight filtered through the tent’s white walls. But it was still Art Week: loud, crammed, crowded.

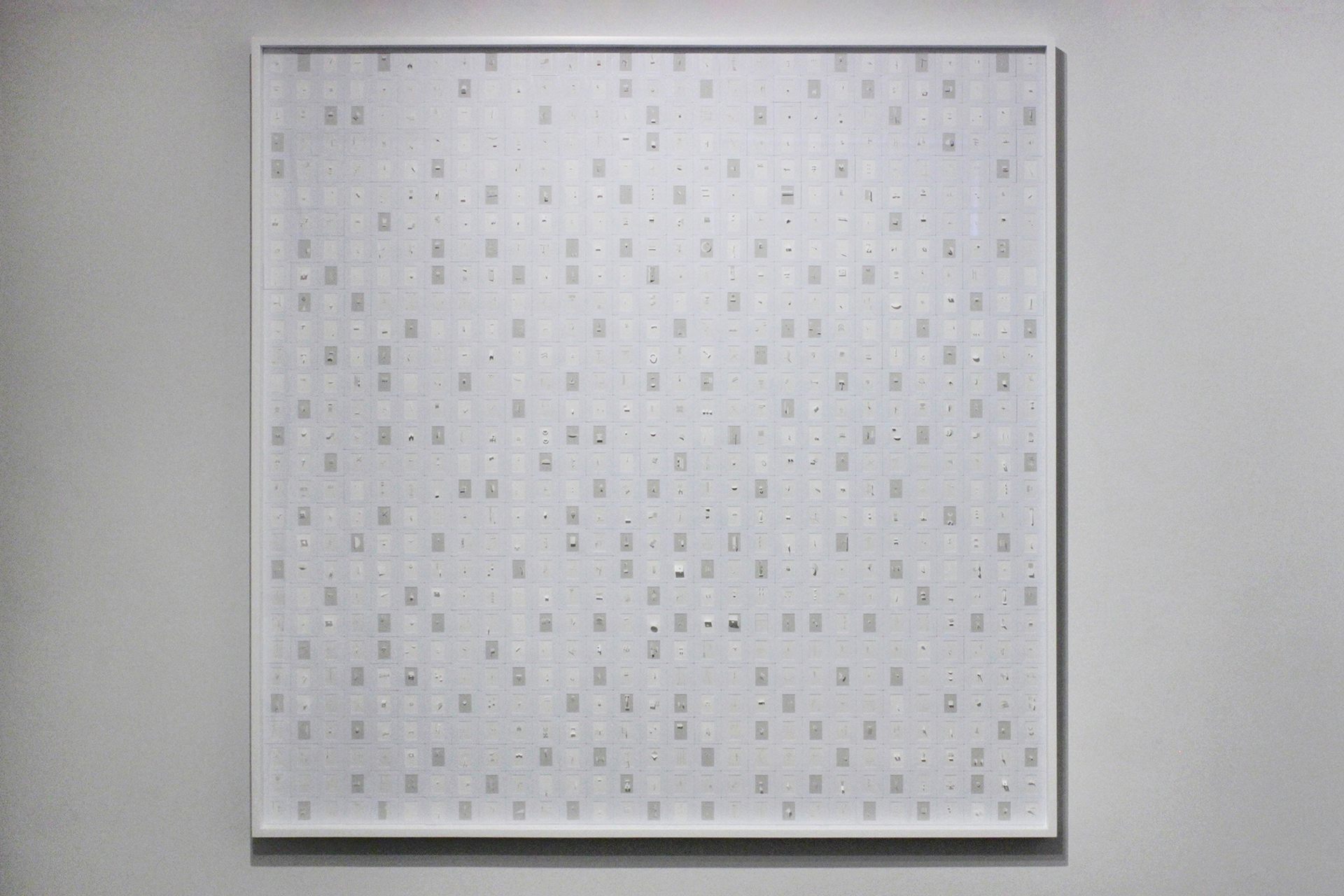

Then we saw “Spelling Square,” a piece by Marco Maggi at the Josee Bienvenu Gallery booth. It was like some elegant flock of tiny little birds had flown into the tent and rested before our very eyes. A field of 841 delicate, white glyphs, each carved out with an X-Acto blade and mounted within 35mm slide mounts on a five-foot grid. Here was the quiet voice that rang out like a bell.

MARCO MAGGI

SPELLING SQUARE (G & W), 2016

CUTS AND FOLDS ON 841 WHITE AND GREY ARCHIVAL PAPERS IN 35MM SLIDE MOUNTS ON SINTRA

59 X 59 INCHES, 60 X 60 INCHES FRAMED

MM229

Marco Maggi

Spelling Square (G & W), 2016

Detail

COURTESY OF JOSEE BIENVENU GALLERY

Marco Maggi

Spelling Square (G & W), 2016

Detail

COURTESY OF JOSEE BIENVENU GALLERY

We spent an hour deciphering Maggi’s obviously alphabetic/semiotic encryptions. We convinced ourselves of the logic. We categorized our findings, argued, agreed, wondered, argued again. At last, we asked the representative from Bienvenu what we were looking at.

She spoke with us at length about Maggi’s work. The pattern we discerned was imaginary; his purpose was to have us create our own system. The work was intentional in its lack of specific intention, in its mission to spur us to take the time to create our own interpretation. This work invited, gently, a collaboration between artist and viewer that gave us room to exercise our intuition and sensitivity. In the absence of narrative, we worked to create our own. One word: sublime.

We hit the café, ordered beers and sandwiches. Sat quietly, the bunch of us. That had been an engagement. Was this the Greatest Piece of Art in Miami? Who cares? It did what great art should do: It froze us in time, made us wonder, made us think and question.

Just down the Beach from Untitled was the Scope tent. Same deal. Crowded. It would require supreme will to hazard its gaping maw. What could be worth seeing after the Maggi?

There it was, right by the entrance, in the Alexander Chambers Gallery booth. Amid a bounty of Ralph Steadman drawings and paintings. A life-size bronze statue of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson himself, hot-footing it toward the exit as fast as his ether-addled legs could carry him.

I stopped him mid-stride for a quick fan pic, and then, just like that … poof … he was gone.

It was a sign.

We bolted and made tracks down the beach. Where a seagull shat on my shoulder. It was exquisitely expressionistic and performative, and it smelled like crab. Whatever. The sunset over the Atlantic was gorgeous. We headed north to our final destination.

At the corner of 17th and Washington, we find Soundscape Park, just across the street from the original Jackie Gleason Theatre. We drop onto the lawn outside the New World Symphony concert hall, amid a $13-million sound array that encompasses approximately 2.5 acres of park with 160 individually powered speakers. Several dozen people drape across scores of comfortable bean bag chairs. Kids scamper, large groups whoop it up, solitary listeners nestle in meditative repose. A few homeless fellows take respite from the nightly grind.

Every night during the two hours before an Art Week film presentation, a compilation of sound works fill the park. Pay attention long enough and you start to recognize the pieces as they loop around. Or maybe you just pass paper bags and blunts and laugh with your pals, maybe shout at the kids to simmer down every now and then.

Molly Palmer’s “Sirens” combines shifting choral harmonies, spoken word, synths, and chiming bells as the most prominent elements, with a subtle weave of traffic and airplane sounds. Soundscape Park sits at a bustling intersection, directly underneath the landing path of Miami International. The traffic sounds in the piece mirror in real time, the sound of a passing bus merging with the recorded bus. A westward bus intersects with a recorded eastbound bus, a real bus passes just ahead of a recorded bus. The sound of airplanes in opposing motion, crowd chatter blending with recorded voices. The sounds linger on a cool night breeze. It takes a minute to realize the sound system has gone quiet.

Again: There’s room here, there’s time, a gap that allows you to not pretend to be a sophisticate in a world full of people desperate to prove that they, too, are sophisticates. In the near darkness — with or without the benefits of ether or ibogaine or even properly made martinis — the Soundscapes invite us to step out of habitual thinking, to step outside workaday space/time and consider existence as something other than a series of meetings or conference calls or things to be fixed/cleaned/built. A place of No Deal.

There’s space for Art — capital A — in this world, even in an environment as fraught as Art Basel Miami Beach. Maybe now more than ever we need that space, something to remind us that life is not all about spreadsheets or political parties or which team is better, whose fortune is huge. It’s not about The Deal, or measuring genitals via fiscal derivatives, or who has the biggest Twitter following. It comes down to connection. When we find it, life is worth living to the fullest.

Without it? We are lost little puppies. Let’s not even go there. We still have a chance.