By Shane Mitchell

“How much sugar goes in sweet tea?”

“’Til it’s sweet enough!”

— “Is It Southern…?”

Corey Ryan Forrester and Trae Crowder, WellRED Comedy

Among the sterling silver service passed down to me, the most idiosyncratic pieces are my grandmother’s six long-handled iced-tea spoons. For a certain generation of Southerners, they are a social signifier nonpareil. Nana spent most of her adult life in a modest walk-up apartment in Queens Village, New York, far from her childhood in the Carolina Lowcountry, but that didn’t stop her from upholding formalities with chilled beverages better suited to a sticky summer afternoon on a porch overlooking a salt marsh. Much like the angel food cake breaker or watermelon pickle fork, it is a utensil designed for a singular task: to stir sugary sediment in a tall glass tumbler. A plastic straw would do, but the iced-tea spoon imparts ritual to a drink involving sufficient sweetener to kill a diabetic.

* * *

Growing up in Shreveport, Louisiana, Brandon Friedman thought iced tea was “gross.”

At age 7, he played backyard army games dressed head to toe in camouflage. In high school, he took the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery test. He studied military history in college and, in his own words, became a “hawkish war junkie.” Voted for George W. Bush in 2000. Movies and a bit of rebellion inexorably fueled his decision to enlist, although his family had a history of service dating back to the American Revolution. One ancestor served in the 35th Georgia Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. But his parents weren’t in the military at all.

“They were horrified,” he says.

Eight weeks after the 9/11 attacks, Friedman was deployed to Pakistan for Operation Enduring Freedom, the official name given to Bush’s global war on terror.

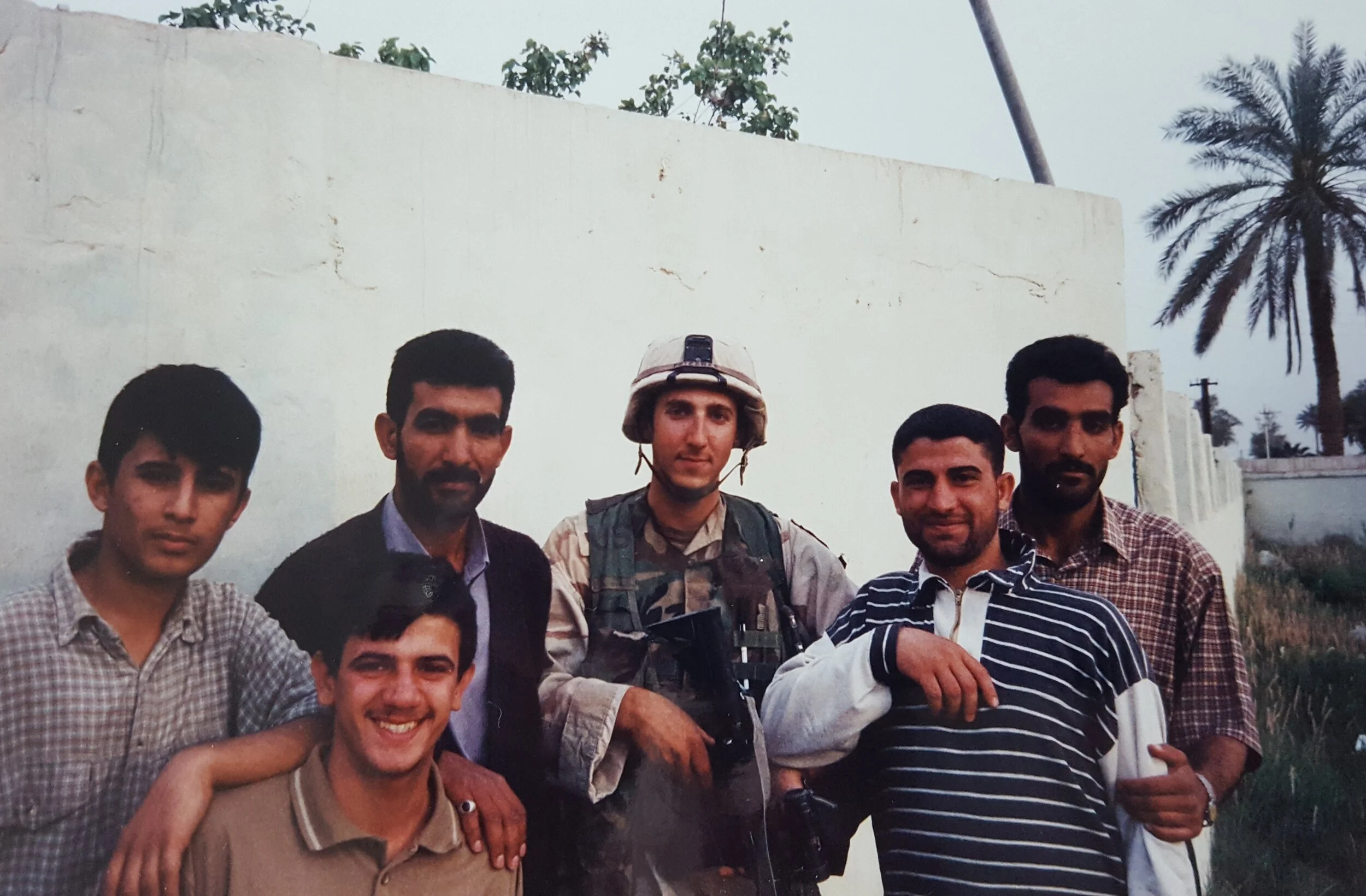

In the desert south of Najaf, during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Friedman (center, wearing scarf) poses with 3rd Platoon Delta Company, 1st Battalion, 187th Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division.

Southerners represent a disproportionate quota in the military — they make up more than 44 percent of the armed forces population — and this tends to be generational, as one of the strongest predictors of service is having a relative in uniform. Veterans typically retire near military bases or move back home, and so prove to be influencers from the same communities again and again. My own family is a case in point. All three of my grandmother’s sons served. A West Point graduate and career Special Forces commander buried at Arlington Cemetery. A naval officer assigned to Admiral Hyman G. Rickover and the nuclear propulsion program. During World War II, my father joined the Merchant Marine, and so now has my nephew. My mother’s brothers served, including a retired Air Force pilot who coincidentally lives in Shreveport, not too far from Friedman’s folks. Ancestors on both sides fought in the Civil War. I’m directly related to Francis Marion, a Revolutionary War general nicknamed the Swamp Fox. This “warrior caste” narrative is the stuff of novels by Pat Conroy, and that’s also how some Southerners get fired up to enlist.

A whip-thin man with bony features and floppy hair, Brandon Friedman appears bulkier in old photographs taken on the battlefield. His unit was the First Battalion of the 187th Infantry Regiment in the 101st Airborne Division — informally known as the Rakkasans, meaning "umbrella for falling," the Japanese linguistic substitution for parachute, and a nickname given to the regiment in occupied Japan following World War II. In March 2002, Friedman led a Rakkasan rifle platoon into Afghanistan's Shah-i-Kot Valley to engage Taliban and Al Qaeda forces during Operation Anaconda; a year later, his troops engaged in combat and counterinsurgency operations during the invasion of Iraq. He marched from Kuwait into Baghdad, then onward to Tal Afar, near what would become Islamic State strongholds on the Syrian and Turkish borders.

He brought back two Bronze Stars. He also came home a tea drinker.

On a late autumn weekday, Friedman and his former machine gunner, Terrence “T.K.” Kamauf, brew cups in their two-room Rakkasan Tea Company headquarters inside an old brick warehouse on Elm Street in Deep Ellum. This historically black Dallas neighborhood was once farmland cultivated by people emancipated from slavery. With the arrival of the Houston and Texas Central Railroad, it became a significant commercial hub for African Americans and European immigrants, and by the 1920s it evolved into an entertainment district where nightclubs, domino parlors, and “tea rooms” hosted early blues musicians such as Robert Johnson, Huddie William “Leadbelly” Ledbetter, and particularly Lemon Henry “Blind Lemon” Jefferson, who lived here for a time. On the way to Rakkasan Tea, I read a bronze plaque commemorating Jefferson, the father of the Texas blues sound, who in 1926 wrote these lyrics:

“I can't drink coffee and the woman won't make no tea / I believe to my soul sweet mama gonna hoodoo me”

— “Dry Southern Blues”

Friedman escorts me through a communal workspace and into the office, where storage racks pushed against bare brick walls hold neat stacks of plastic storage bins and sealed foil bags of loose leaf tea, imported from estates in such far-flung countries as Ethiopia and Sri Lanka. For anyone accustomed to the stale dust in a bitty paper sack attached to a Lipton label at the gas-station takeaway, or the sugar slush in the frosty pitcher at a meat-and-three, these teas are from other worlds entirely.

Dressed in faded jeans and a striped sweater, the 41-year-old veteran briefly outlines his career after leaving active duty in 2004: finished a master's degree in public affairs, worked at the Department of Veterans Affairs under Tammy Duckworth (now a U.S. senator from Illinois), and then at the Department of Housing and Urban Development during Barack Obama’s second term. When President Donald Trump took office, Friedman dialed out of Washington, D.C., and relocated to Dallas with his Romanian-born wife and their young son. He launched a Kickstarter to fund this tea company.

“I learned tea and war,” he says.

Friedman in Iraq, April 2003 (Names of other men pictured and exact location not disclosed)

“We worked with Iraqis every day. City officials, village elders. Any time there was business to be done, it was always discussed over tea. We hired translators who lived with us, and they were making tea all the time as well. Black tea, low to mid-grade.”

He pulls tins off a shelf and opens them for me to smell, then pours bottled spring water into a Mr. Coffee electric kettle to boil. Friedman likes the exactness of the digital readout, but learned to prepare tea in less than ideal circumstances and can accurately judge brewing temperatures by the corresponding bubbles and steam.

“When we were in Iraq, everything was always go-go-go with missions, but when they're making tea then you've got to slow down,” Friedman says. “It was a respite or an oasis in the middle of chaos to drink tea with these guys. And it forced us to take a break. To this day, when I drink tea, for me, it's a calming thing.”

Terrence Kamauf, 40, quits packing orders in the other room to join us. The former Green Beret wears camo sneakers and a hoodie with an embroidered patch bearing the 187th Airborne Infantry’s motto, “Ne Desit Virtus” (Let Valor Not Fail). He graduated from the U.S. Army’s Ranger School and served in the 5th Special Forces Group, staying on for two more tours after Friedman departed for civilian life. When Kamauf separated from the military in 2011, he moved to Houston and worked in the oil and energy business, and then reconnected with Friedman again two years ago.

Terrence “TK” Kamauf (left) and Brandon Friedman (right), outside Rakkasan Tea Company in Deep Ellum, East Dallas.

“Why did you enlist?” I ask.

“I came in at the lowest rank you could be,” he says. “I was still living at home and worked for the street department, and after about a year of that, I was like, I can't wake up in 20 years and still be fixing potholes, so I called in sick and a recruiter picked me up. Came back and my mom said, ‘Why was your car in the park-and-ride lot all day? What did you just do?’”

He crosses muscular arms and leans back in a folding chair as Friedman set up a glass IKEA teapot with a removable strainer on the desk. They met in Afghanistan in 2001.

“Never 40 feet apart at all times,” Kamauf says.

“Did you grow up drinking tea?” I ask.

“No, I grew up in Pittsburgh.”

Both veterans laugh.

“Oh, he always references the South and that he drank sweet tea growing up,” says Kamauf, grinning. “Well, everybody in the South drinks iced tea. You go to a restaurant, it's like, ‘What d'you like? Water or tea?’”

“I've never had an address outside of a former Confederate state,” Friedman continues. “But living in northern Virginia was completely different from living in Shreveport. When you're from Louisiana or Mississippi or Alabama, you don't consider Virginia as Southern.”

Kamauf interrupts.

“A funny joke I always heard: What’s the most Northern Southern state?”

Friedman shrugs.

“Florida.”

Friedman sets the timer on his phone and measures several ounces of Phou San Mountain Dark leaves on a kitchen scale.

“So this one comes from Xiangkhouang, in northeastern Laos, the most heavily bombed province during the Vietnam War,” Friedman says. “There's still a bunch of metal on the ground, but not where they have the tea fields.”

“My uncle Bob flew B-52s during the Secret War. He’s the one who lives in Shreveport now.”

Friedman and Kamauf nod, serious again.

When drafting a mission statement for Rakkasan Tea, they focused on sourcing from former war zones, places where economic development would have the most social impact. Among others, a tea estate in Rwanda’s fertile Rukeri Valley that is at the forefront of banning child labor and supporting workers’ rights; in the Tumaco region of Colombia, once heavily occupied by FARC guerillas, an organic farm in the Andes cloud forest that blends a hybrid black tea with bitter cacao husks and nibs from small producers. And their list of source countries is expanding.

“We pretty quickly realized that there was a lot of good tea being grown in post-conflict countries that wasn't really reaching the U.S.,” says Friedman. “I've also seen what war does to communities and how much effort it takes to get those communities back together, functioning again.”

The Laotian tea tastes of honey.

Both Friedman and Kamauf have completed two of the three certification courses of the Tea Association of the USA's Specialty Tea Institute based in New York, and learned how to pick and hand-roll leaves on a farm in Mississippi - home to one of the few existing commercial tea fields in the South. Kamauf admits it was one of the hardest things he’s ever done, which is saying something for a man who completed Special Forces training at Fort Bragg in North Carolina.

“Do you put sugar in your tea?” I ask.

“As a 21-year-old kid, the more sugar the better, you know?” Kamauf says. “And the way they do it in Iraq? They put the sugar in first and then the tea, and stir it up. But Hameed, our interpreter, was an older guy, so I watched him. He didn't stir it. Drank the tea and all the sugar just sat there at the bottom. He's like, ‘I can’t drink this all day.’ So I got the point. I was curious how good the tea actually was, and yeah, if we put sugar in some things now, I don't even like it anymore.”

We pause for tacos.

* * *

French botanist Andre Michaux introduced the first Camellia sinensis tea shrubs to America at Middleton Barony on the Ashley River outside Charleston, South Carolina in 1795. Sinensis means “from China” and is the variation of the camellia genus most commonly used for tea. Assamica is the other. Growers process harvested leaves in different ways to attain varying levels of oxidation, from white to green to oolong and black. Shape and grade of leaves matter, too. During the late 18th century, green tea was already a favored ingredient in Southern militia punches — spiked with sufficient booze to knock a battalion on their asses — definitely not the stuff of children’s birthday parties or church picnics. Early Southern cookbooks contain recipes for Charleston Light Dragoon Punch and Chatham Artillery Punch, a potent cocktail preferred by an elite Savannah unit. In The Kentucky Housewife (1839), Lettice Bryan included a foundational punch recipe that poured strong, boiling hot tea over one-and-a-quarter pounds of loaf sugar before adding rich sweet cream and either Champagne or claret wine. She instructed: “You may send it round entirely cold, in glass cups.” And the oldest located non-alcoholic sweet tea recipe comes from Housekeeping in Old Virginia (1879), a community cookbook by Marion Cabell Tyree:

“Ice Tea. – After scalding the teapot, put into it one quart of boiling water and two teaspoonfuls green tea. If wanted for supper, do this at breakfast. At dinner time, strain, without stirring, through a tea strainer into a pitcher. Let it stand till tea time and pour into decanters, leaving the sediment in the bottom of the pitcher. Fill the goblets with ice, put two teaspoonfuls granulated sugar in each, and pour the tea over the ice and sugar. A squeeze of lemon will make this delicious and healthful, as it will correct the astringent tendency.”

Antiquarian Charlotte Crabtree of the Silver Vault in Charleston says the first documented iced-tea spoons appeared during what she refers to as the gilded age of the American silver industry. After the discovery of the Comstock Lode in 1859, showy sterling “event” pieces began arriving on the dining tables of wealthy Southern families. By 1895, Gorham Silver’s catalog included iced-tea spoons in several patterns, including the widely popular Chantilly and Versailles. (My grandmother’s pattern was Fairfax, patented in 1910.) Other silver companies followed suit.

At the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri, iced tea became widely commercialized when Richard Blechynden, India Tea commissioner and director of the East India Pavilion, chilled brewed tea in a lead-pipe apparatus, and offered it free to fair attendants during a blistering hot summer. Black tea eventually became more popular in iced beverages because it was cheaper to import; by the end of World War II, Americans almost completely shifted their palates to black over green teas, thanks to trade blockades in Asia.

***

Deep Ellum still has a heavy concentration of bars and live music clubs. Friedman and Kamauf walk me past a mural on Commerce Street depicting blues legends Mance Lipscomb and Lightnin' Hopkins, then we sit down for al pastor smothered with pico de gallo at Revolver Taco Lounge, where Friedman confesses he still likes MREs enough to contemplate packing them on a camping trip with his son. Afterward, we return to the office, where he heats another pot of water to precisely 175 degrees, slightly lower than a full boil. He measures a precious handful of wild-grown green tea harvested from 300-year-old trees in the northern province of Hà Giang, Vietnam, where indigenous Hmong women wearing woven tea-gathering baskets climb ladders to reach the top leaves.

“We wanted good Vietnamese tea because it's a cradle of tea country,” says Friedman.

Vietnam is also one of the few countries where wild tea trees exist, most likely spread with the migration of nomadic tribes among the mountain ranges on the border with China. Friedman pours the golden-hued tea into plain ceramic cups, and we sip slowly. It smells of wood smoke. He unrolls some leaves, spreading them on his hand to show me their fullness.

“I feel guilty when I make this tea, even if I steep it a couple of times, because I know how much work went into this,” says Friedman. “This right here would take me an entire day to pluck.”

Tea experts often refer to the act of brewing as “the agony of the leaves.” As rolled leaves rehydrate and expand in boiling hot water, they writhe in a painful dance. This also seems an apt metaphor for a trauma known as “moral injury.” According to the National Center for PTSD at the VA, moral injuries in war stem “from direct participation in acts of combat, such as killing or harming others, or indirect acts, such as witnessing death or dying, failing to prevent immoral acts of others, or giving or receiving orders that are perceived as gross moral violations.”

“Most people who have been in combat just get dumped,” says Friedman. “Like, good luck, you know, good luck with your life. There's no come-down, no reintegration. A lot of people struggle with that. My first round of PTSD treatment was with a 70-year-old psychiatrist who had never been in the military. But he was great, like a fucking yogi, a shaman.”

Friedman shows me a photograph of himself as a boy, carrying a toy gun, at his parents’ home in Shreveport.

“Did you grow up hunting?” I ask.

“No. I’ve never killed an animal.” He stares at the teapot, signaling an end to that part of the conversation.

My father’s brother, the Green Beret, rarely talked about his three tours in Vietnam. Four more of my uncles and cousins deployed there, too. Last year, I finally went myself, tracing their steps in Saigon and Da Nang. Stood on China Beach. Saw the abandoned hangers where planes sat between bombing runs to Laos and Cambodia. It was an agonizing experience for someone who grew up witnessing the war secondhand through the brutal photojournalism of LIFE Magazine, and overhearing arguments between my father, an evolved pacifist, and my grandmother, who loved Richard Nixon for bringing her son home safe. Drinking jasmine tea from Yên Bái with Friedman and Kamauf brought that back into sharp focus. And on the same November day we sat in cramped quarters deep in the heart of Texas, talking about tea and combat, President Trump pardoned three servicemen accused of war crimes, a controversial decision disrupting long-held standards of military justice and the role of commander-in-chief.

The underlying mission for Rakkasan Tea, by contrast, is to make its customers think more deeply about peace in landscapes marred by violent conflict or oppressive regimes. The Republic of Georgia and Myanmar are next on their acquisition list.

“What do you do when not selling tea?” I ask.

“I got two kids,” says Kamauf, rubbing his short-cropped hair. “One will be 6 next month, and the other is 3. So, a lot of wrestling. And I watch ‘Mickey Mouse Clubhouse.’”

Friedman and Kamauf slurp their tea noisily. It’s not considered rude where they learned to drink it.

“We still try to stay true to the way we learned tea, rough around the edges and maybe not so particular,” says Friedman. “We're not British afternoon tea. We're not Japanese tea ceremony. We are guys sitting around in plastic chairs with bandoliers of AK-47 rounds, with a little gas heater, drinking earthy, black tea, and we put a bunch of sugar in it.”

He still doesn’t drink iced tea, but for a hot summer day, admits to liking cold brew steeped in the fridge.

Whether you come to the act of drinking tea by way of sterling spoons inherited from your Nana, or chipped glasses at your interpreter’s house in Baghdad during a lull in an insurgency, the truth about hospitality proves to be a universal one.

Stay sweet.

Journalist Shane Mitchell has received three James Beard Awards for her problematic crop and food insecurity stories. You can hear her report on okra in Season 2 Episode 3 of the Bitter Southerner podcast. Follow her on Instagram @shanefarafield.