Who is the very model of the modern Southern gentleman? The Bitter Southerner thinks that should be determined by the gentleman’s actions — not his clothes. Bill Smith is our model. For more than 40 years, Smith has played pivotal roles in the evolution of Southern culture. In the 1980s, his nightclub, the Cat’s Cradle, provided a home for Southern musicians of every stripe. Since the ’90s — as the chef of the most quietly influential restaurant in the South, Crook’s Corner in Chapel Hill — he has nurtured an amazing evolution of Southern food as our region grew more multicultural. If you believe respect for tradition should co-exist with the graceful acceptance of change, you’ll find no better model than Bill.

Story by Tom Maxwell | Photographs by Kate Medley

If one works within tradition the right way, tradition cannot be told from innovation.

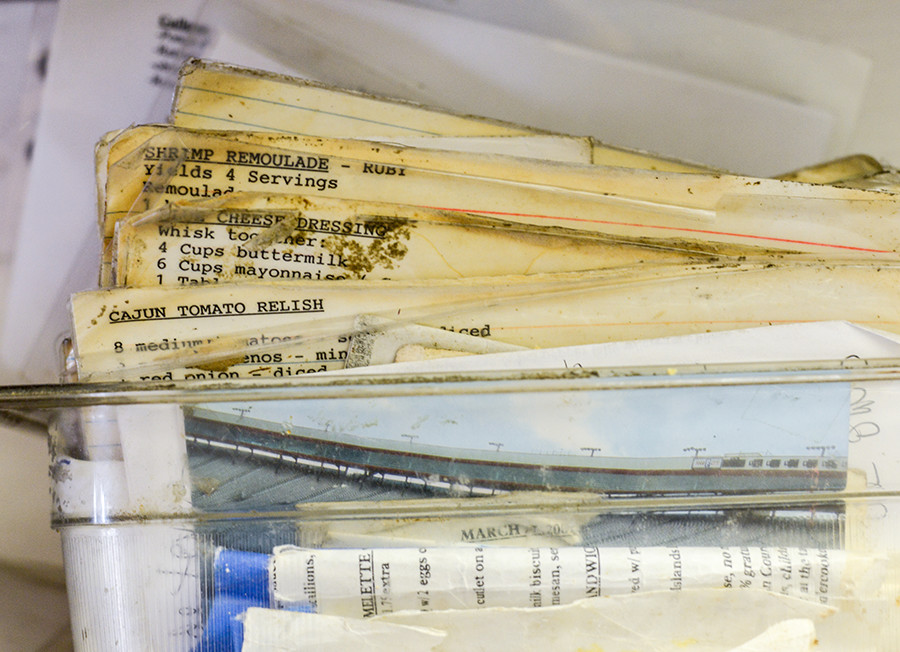

Bill Smith is an exemplar of this approach to Southern food. For more than 20 years, he has been head chef of Chapel Hill’s venerable Crook’s Corner. He has expanded the orthodoxy of Southern cooking in his own inclusive way, inventing dishes that seem now to have been with us always, including the phenomenally successful Atlantic Beach Pie. He knows the cuisine’s history of seasonality as well as its wondrous diversity of influence, and moves it forward with quiet authority. The James Beard Foundation has nominated Crook’s Corner as a Best Restaurant in the United States, and twice nominated Bill Smith for Best Chef in the Southeast.

He doesn’t mention any of this when you talk to him.

My first bartending gig was at Crook’s Corner, several years before Bill Smith took over after the death of founding chef Bill Neal. I worked there four nights a week so I could rehearse with my band the other three. (There, I learned the honorable skill of service: It’s not about being lesser-than. It’s about acknowledging someone, through simple acts. It’s about treating everyone with the same basic dignity.)

Our band played the legendary Cat’s Cradle, a club Bill helped open. When I left town, to tour the world with the Squirrel Nut Zippers, I came to understand Chapel Hill as a rare place of nurture and community. Bill Smith embodies these things. He is an omnivore — of food, of art, of music. He has devoted his life to what binds us together.

I am now in my third career as a writer, a skill reliant upon understanding and memory. It was a pleasure, in this capacity, to have a lengthy, discursive and completely enjoyable conversation with Bill Smith for The Bitter Southerner. We talked over two days a few months back.

In which our hero begins a life of gustatory splendor, with little practical experience.

Tom Maxwell: I just want to start at the beginning, with you as a child and your earliest associations with food. Was cooking familial? Did someone teach you? Or did you have no interest in it at all?

Bill Smith: Actually, I was very lucky, given how my life has turned out. I grew up in eastern North Carolina with a million great cooks around me. My great-grandmother on my mother’s side, my grandmother and aunt on my mother’s side, aunts on my father’s side, they were all fabulous cooks. You always expected everything to be wonderful when you sat down. There was no such thing as sitting down to bad food, ever. That gave me the foundation of that expectation. When it turned out that I was a cook myself, the standard was already sort of set for me.

I have countless memories of things we ate when I was growing up. It was a huge deal. Our food was a big deal. My father’s sister-in-law was from Georgia, and she had a style of cooking that was a little more traditional than the cooking on my mother’s side of the family, because they were recent German immigrants. There was a little bit more European [influence] in what they did, although they were cooking Southern, too.

Principally, it was my aunt on my father’s side who was the cook at that household. She lived with her husband and his mother, my grandmother. She ran the kitchen in that house, and my great-grandmother for the most part ran the kitchen in the other house, so there were several kinds of food being given to us all the time.

My Aunt Hi, she was Daddy’s sister-in-law. Her nickname was Hi, H-I. She was one of those who loved to cook. She saw it as clearly a pleasure. She loved to sit down and have a fit over what she put in front of you, and she was one of those people who, if you weren’t about to pop open when you got up from the table, she did not understand why. "You haven’t eaten enough. Eat more. Eat more!" And she would cook things that she knew you liked because of that — so you’d eat more, I guess.

I think mainly about Sunday lunch at her house. It was always a big deal, with many vegetables and many courses. It was very informal, but it was a bounty. I think it was chicken and pastry, she called it, which was like a chicken stew with ribbons of dough in it. She was a great dessert cook. She loved to make pies and cakes. She loved to make fried chicken.

On the other side, my great-grandmother, my mother’s grandmother, her house was right downtown. She cooked a big lunch every day for everybody in the family that could get there from work or school.

Tom: Downtown where? What town were y’all in?

Bill: New Bern. Grandmother on my mother’s side — we called her Grandmother, although she was our great-grandmother — she cooked this huge lunch every weekday, and her daughters came back home from work to eat. I came over from school. Various uncles and aunts who happened to be free would show up and, occasionally, a guest. It was a big deal, too. It was china and tablecloths and table napkins and the whole deal, but just for one hour, since that’s all anybody had. That was always delicious. I did that all through my adolescence. When I was little, I didn’t do it because we didn’t live that close to her house, but when I was in junior high school, it was in her neighborhood, so I was included in those luncheons.

The cooking of both of those people I mentioned was very seasonal, as was everyone’s in those days, I think. Like I said, it was always good, and you had lots of favorites. You always looked forward to them. You couldn’t wait for such-and-such to show up.

Tom: What were your favorites?

Bill: Oh, God, I don’t know. Everything. I loved everything. What would Grandmother make that was really good? She had a pecan pie that was delicious. She made all these things with corn and field peas as a side dish, or she also — and this was unusual in eastern North Carolina — she cooked leg of lamb, and she cooked it so it was absolutely falling to pieces. I loved it. We had all kinds of seafood. That was the Catholic side of the family, so there was all kinds of seafood on Fridays, because you weren’t allowed to have meat on those days.

Tom: Were you ever enlisted in the kitchen with these aunts and grandmothers?

Bill: No, never. The only thing I was allowed to do, ever, was my great-grandmother would make blackberry pies if I would pick the blackberries. That was the extent of my involvement. I was allowed to watch and hang out. With my Aunt Hi, a little more. She sort of enjoyed having me in there to talk to while she cooked, but Grandmother she didn’t want anybody in the way. Even when she was very old, she would be on a walker and still cooking. I can remember her making gravy in the roasting pan, leaning on a walker, but no, you didn’t bother her in the kitchen.

On why Chapel Hill is an artistic sourdough starter that never dies.

Bill: I came to [the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill], but I was a horrible student. I was hanging out where there was music and waiting on tables. I dropped out early on. I made it about a year and a half. I was a terrible student. I liked being here, but I was bad at sitting down at a desk. I’m better at it now, but back then, there was no way. Coming from eastern North Carolina, I’d had to behave for 18 years. I just could not wait to get loose of that. This was the perfect place.

Tom: It reminds me of my own experience, when I finally ended up working at Crook’s. I made enough money working a few nights a week for the band to be able to rehearse three nights a week. After work, we’d go out to the Cradle to see who was playing. “We’ll drink a beer and see if they’re any good.” The cover was $2.

Bill: That’s the best way. I still do that. Not as often. I can’t just hang out in bars all the time, and I hate to be hungover, so I behave better. Sometimes I’ll just think, "I wonder who’s playing," and I’ll go. Even if I don’t really like it, I appreciate the creative effort involved. I like lots of things, so I’m always interested in what people are doing.

Tom: Chapel Hill, to me, is a special little world that I treasure in memory and grieve in imagination because I feel like it’s all gone, but you’re telling me it’s not.

Bill: Oh, no, it’s not gone. It’s different. Now, everyone can publish themselves and record themselves. They don’t need record companies anymore. You can do it on your phone, practically. There’s so many people now you can’t possibly keep up. Once upon a time, you could keep up with who was who and who you wanted to see. Now, you may or may not. It’s different in that regard, but the art and magic are still there. It just manifests differently now.

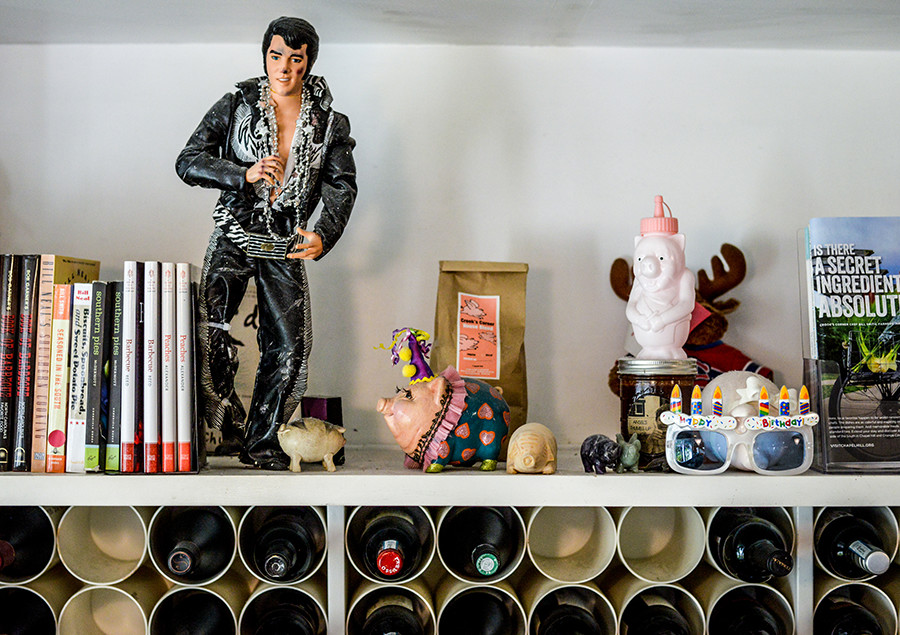

I have to say that the one reason I stayed here all these years was not the restaurants: It was the music. There are lots of people working in restaurants who are musicians. I love that. They have that work-hard/play-hard attitude that you need in a kitchen, too. They always tend to be smart people — and maybe argumentative and difficult, which creative people are, often. It’s all the same pack of dogs to me, the cooks and the musicians.

In which Bill Smith becomes an accidental chef, and an “impresario of people’s good times.”

Tom: At some point it was revealed that you were a cook.

Bill: I found out I was a cook as an adult. It never occurred to me until I was probably in my late 20s that [cooking] might be a job for me.

It was when I went to work with Bill [Neal] at La Residence. I was actually going to Europe. I was going to join my boyfriend in England, and I didn’t have enough money. One of my roommates, Susan Perry, was the head waitress at La Residence. She said, "I think they need somebody to peel potatoes or whatever." I was given that job, and chopped parsley and all that kind of stuff. It was cool. I liked it. It was fun to be there.

When I came back, I was rehired. By then, I realized that the aesthetic of this profession suited me. I would never have guessed it in a million years. That’s when I sort of jumped in with both feet, because I really loved doing it. It was serendipity. It was like tripping over it. It wasn’t a goal, ever, until I got into it, and then, of course, it became one.

Tom: The food-service industry is often the recourse for the wanderer.

Bill: It is. I had worked in restaurants before, but not in a serious kitchen. In Chapel Hill in the ’60s and ’70s, you could wait tables a couple of nights a week and live with a bunch of your friends in a big house and just have a big old time. I had been waiting tables and doing line work at a coffee shop, and that was fun and really suited me. You didn’t have to behave yourself.

[With La Res, it was] the mid-’70s, and I just did what I was told. I was the low man on the totem in the beginning and you learned all the time. It was great. It was exciting, and French cooking was new to me. I liked pretty much everything I had, and, like I said, the expectation was good food so it was the way I had grown up. It was a good fit.

Tom: You mention the "aesthetic of the profession." That’s an interesting turn of phrase.

Bill: I grew up where the dinner table was important. I guess it occurred to me that you could transfer that importance to a profession. It’s always appealed to me. I’ve always enjoyed the idea of sort of being an impresario of people’s good times. I might like to bring them good food, and I see that as the reason they come to sit down, but I really like sort of instigating parties. The fact that you could do, for a job, something where people come in and be loud and be with friends and have a great time — that’s the aesthetic I’m thinking about.

Then, there was a certain standard of good cooking that sort of goes hand-in-hand with that — if your really splendid food would give you an even more splendid time, perhaps. (Although I have to say that if you’re in a wonderful restaurant with people you don’t like, it’s that much worse, so maybe that’s not true.)

When I owned the Cat’s Cradle, it was the same thing. I loved the idea that even though they might end up as an accountant, one night I had them dancing on tables. It’s just the devil in me, I guess. You know what I mean?

Bill’s other, lesser known, sideline: kickstarting the Chapel Hill music scene.

Tom: You owned The Cradle?

Bill: Yeah, we started it in 1971 and sold it in ’84. As you know, I love bands and music and all that stuff, and I just can’t wait to get off work and run across the street and hear who’s playing. Working at restaurants was actually the way we kept the Cradle open. We were such poor business people that we never made any money. We were always in trouble with tax people. Bounced checks all the time and all this kind of stuff, so we’d all wait on tables. That’s how we kept The Cradle open all those years.

Tom: Who were the other partners?

Bill: It was a woman named Marcia Wilson and then David Robert. Marcia was from the Eastern Shore of Maryland. When her father died, she inherited a little bit of money. She’d become interested in folk music, and her brother lived in the West Village in New York. He knew Dave Van Ronk and people like that, and she decided she wanted to start a little club somewhere. First of all, she went up to Saratoga Springs, New York, to the Caffè Lena. I think [the Cradle was] based on the Caffè Lena, which is a famous nightclub up there. Her friends said, "Check out some of these college towns in the South." She went to Charlottesville, then she came to Chapel Hill and she stopped here. She said, "This is where I want to be." She used that little bit of money. In those days, you could do things like that. I don’t know how much it was, but it was enough to put down the deposit on the premises and get yourself a beer license and buy a cooler. We were off and running.

In those days, music here was bluegrass-y or folk. That was the music of the times and the room was small, but that suited that kind of music. Then, by the time we moved down the street to the Skylight Exchange Building, it was the beginning of New Wave — the rock bands that were good at little rooms. [The Cradle] was a small room, so it just sort of grew with the culture, as it were.

Tom: Why did she pick Chapel Hill?

Bill: I’m not sure. I didn’t know her right when she got here. I came in about a year after she had gotten going. She had been involved with some other people who were songwriters, and they decided they didn’t have time. She was looking for somebody else. She, unhappily, was killed in a wreck in the mid-’70s. It was a terrible thing. It was so upsetting. We owe her a great deal. I think of her often. She was a very kind person. An extremely generous person, and she had a beautiful voice. Knew all kinds of things about all kinds of music. She was really a wonderful friend. She did us all a great favor. She was the foundress.

Or, when necessity became a lifestyle.

Tom: Now, La Residence served French food, is that correct? Proper French?

Bill: Well, no. It was actually what we call cuisine bourgeoise, which means “everyday cooking” or “the cooking of the middle class.” It wasn’t fancy. We didn’t try to flambé things at the table and stuff like that, but we used Julia Child as one of our guides — those two volumes of “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.” We did stuff like filet mignon and coq au vin and all the standards, but this was the cooking of a proper household in France. It wasn’t like the fancy, four-star Michelin thing going on. It was just the food that people ate every day, but in France. And, actually, in the South as well; I see this relationship all the time. People would expect all their dinners to be good. They sit down to it, and it’s important that people know how to cook and all that kind of stuff. That was what this was. This was delicious dinners. It was sort of a reward for a hardworking life. You know what I mean?

Tom: Then suddenly, old limitations like seasonality became a lifestyle choice.

Bill: That was all a symptom of post-World War II modernization. It was “get rid of all that drudgery.” It’s a new-world kind of thing. We were in town, but the country wasn’t far away. The people who were cooking for me were from a generation that was more familiar with that style. Whereas, my mother’s generation couldn’t wait to get out of the kitchen. They had things to do. The next generation, all the women worked. It’s rare that there’s a stay-at-home wife now, I think. Things changed around us. Now, it’s an effort to get back to the old things, in a way, but you just have to put your mind to it.

A Story, as related to me by a musician friend

Carl Perkins, the ’50s rockabilly star who wrote “Blue Suede Shoes,” is out to dinner in the early 1990s. His friends take him to a fancy restaurant. One of the dishes features Free Range Chicken, and it’s expensive. Carl doesn’t understand what could be so valuable about chicken.

“What’s Free Range Chicken?” Carl asks the waiter.

“Well, sir,” the waiter replies, “it’s a bird that has never been caged. In its life it was free to roam where it wanted.”

Carl listens, incredulous. “Sounds like yardbird to me!” he snorts.

A side note about Bill Neal, who was instrumental in elevating Southern cooking.

Tom: One of things I really want to touch on is, of course, Bill Neal, who hired you at La Residence and whom you replaced at Crook’s Corner. You know Bill’s been gone for more than a minute now...

Bill: Mm-hmm. ’91. It’s a long time. I never worked with him at Crook’s. He was gone before I came to Crook’s. I never worked with him after La Res. I came in [to Crook’s] to eat, but no, I stayed at La Res. He had been dead like five years before I came to Crook’s, I think.

Tom: But in my mind, this far down the road (and not being completely conscious of what Bill was achieving when I knew him), I feel like he was up there with Paul Prudhomme in terms of elevating a regional cuisine to national status. He had an assist from Craig Claiborne and whatnot, but he was a fine writer — which didn’t dawn on me until I sat down and read what he actually wrote — and also I think he was sort of plainly a genius.

Bill: I don’t know. It’s funny. I honestly don’t think about him very much because I’m so busy. I don’t have time to worry about legacy.

But interestingly, I just got asked by Garden & Gun to do the Bill Neal entry for their encyclopedia, so I’ve had to sit down and think a little bit about it. What I’ll say, and what I’m writing about him, is that he saw that Southern cooking deserves the same sort of respect that other sort of cultural cuisines deserved, because the South was sort of looked down on as hillbillies or whatever by a lot of the rest of the United States. He saw that, no, at the dinner table, we’re up there with everyone else. That is what he acted on. He showed it time and time again at Crook’s. "It’s delicious. Shut up! It’s good." That kind of thing. That’s his legacy as much as anything. He just had the vision and sort of the persistence to insist that people see that.

Tom: He had the good sense to follow around some talented black women, too, from what I understand.

Bill: Yeah, probably. That wouldn’t have been unusual in the South anyway. You learn from who you learn from. It’s a matter of where you end up.

Tom: Frying chicken is a very, very difficult thing to do, and it was good that he learned how to do it correctly.

Bill: No, we do it all the time. I do it at Crook’s. We serve it cold. We’re sort of famous for what we call a “picnic late” in the summertime. It’s cold fried chicken, potato salad and watermelon and deviled eggs. I’ve certainly fried enough of it at this point. I just did it for a 100 in Alabama last Thursday and that’s what we did, because they ordered a church picnic. So, last Thursday night, I cooked fried chicken for 100.

How to Fry a Chicken

In the words of Bill Smith

We brine it the day before and then we cut it up into edible pieces, of course. Drumsticks. We cut the breast in two. I use two old, cast-iron dutch ovens. One, I brought from La Res (because I used to cook soft shell crabs in it over there). The other, I bought when I came to Crook’s. It’s just cooking oil — whatever that is. That’s different all the time. This is really important, actually — after you take it out of the brine, you put it in buttermilk. And then your breading is self-rising flour with salt and pepper. The self-rising flour and the buttermilk gives you this big, huge, giant crust, which is what I love the most. I have no use for people who don’t like crust on fried foods.

Then, you have to cook it by parts. You cook all the wings together. You put all the legs together, and that way it cooks similarly. You have to keep a thermometer nearby because if the oil gets cold, it turns greasy. Then, if the oil gets too used, you have dump it out and get new. That’s important, too.

Good leaders, like good cooks, accept influence and incorporate good ideas.

Tom: What’s your kitchen like on a good day? How do you like to run it?

Bill: I have a sous chef I let run it. His name is Hector Gonzalez. He’s from Pueblo, Mexico, and I trust him completely. He comes from a different food background. I think he thinks it’s sort of silly that people will sit and coo “ooh” and “ah” over a bowl of raspberries or something. Like I said, if that’s what they want, that’s fine. He’s got children and so he needs a job and he wants to do what I want. I’ve had a bunch of the guys in the kitchen now. Ricardo and Hector and Israel and Mauricio been with me for at least 15 years, and a few of the other guys have been there at least 10. It’s funny. I don’t even have to be the boss anymore, honestly. I sort of direct and conduct, and they know what I want. We know how each other are. We love each other really. Anyway, I love them.

I think maybe it’s a different scene than some kitchens. It’s not very structured. They’re not above putting ice in my underpants or something. I can’t imagine some chefs allowing that, but I think it’s hilarious. I’m not set up the way some kitchens are, but it works for us. They work hard when they need to, and then, if they want to kick the shit around the steam table when there’s nothing to do, I don’t care. Everybody gets treated the same. They get paid whatever Gene [Hamer, Crook’s owner] decides he can pay them. When I first came there, there was just dishwashers. There weren’t any Mexican cooks that I recall. The reason they were there — and this is something to keep in mind: North Carolina in the ’80s and ’90s, was a boomtown. It was going crazy. That’s why they were here. They weren’t victims of exploitation, and they weren’t Al-Qaeda, they came because there was work that nobody would do. They came up to clean toilets and pluck chickens and wash dishes and all that kind of stuff.

When I came there, nobody talked to them or anything. Not very much. They were over in the corner talking Spanish. I just decided that I wanted them to be a part of whatever we were doing. In the kitchen, a lot of them were students and they would come and go, but the Mexican guys always stuck around. I can’t remember who the first one was. Jorgé Martinez, I think was the first guy that when I was short-staffed said, "Well, you know, I can do that. I’ve been watching."

So, sure enough, he did. That’s something I learned actually from Bill Neal. He worked people up through the ranks, so when there were openings, and one of the dishwashers wanted to come over to the stove or come over to the salads or something, it was fine with me. By then, my Spanish was pretty good. I had studied it a long time ago, but I hadn’t used it in years, and so I just moved them over and they stuck around. They didn’t go anywhere. All of a sudden, they took over the kitchen. Not because I was out looking for them to have that happen. That’s just what the circumstances were.

I go down there to Celaya [Mexico], which is where those guys are from. I haven’t had time in the last year or so, but I’ve been going down and hanging out with the guys that have gone back home for years now. I love doing that. I’ve often thought of retiring there, quite frankly.

Tom: This is an interesting and valuable thing, this idea of being worked up through the ranks. It seems to me that, when you told me that you learned a lot at La Res, it’s because they were probably moving you to different stations.

Bill: Oh, yeah. You did what you had to do that day. In a little kitchen, you have to do what they tell you. "Today, you have to go do this." “But I’ve never done that.” “Well, you’re going to learn right now.”

I don’t know if it’s typical or not, but Bill certainly did it. It seemed like a good idea to me, and it’s worked out for me really well. By and large, there’s always a problem occasionally, but honestly not. If you put some effort into making things work, you can do it.

Tom: I don’t think there’s any orthodoxy to cooking, even though people will tell you different, but it seems to me Southern cooking has a lot of African-American influence and Native American influence...

Bill: Oh, yeah. Everything is evolving. There’s a great deal of Latino influence in Southern cooking now. There are half a million Mexicans living in North Carolina. One thing I’ve noticed is that nobody complains about things being too spicy anymore. It used to be that "the collards had too much pepper." I never hear that anymore. That’s a small example of how things change.

Their horizons have broadened. They’re more used to more things. There’s always some people who think there’s only one way to do things. Usually it’s something like, "Mama’s potato salad is the only one that’s worth a damn. If you don’t do it that way, don’t do it." But people have a broader view of the world now, I think. They can’t help but have that, and they’re open to different things. You can do things that are sort of experimental from time to time, or you can alter things when you see a better way of doing it.

I’ve switched from Southern-style hominy to the hominy that Mexicans use in posole because I think it’s much better. It has a good nose to it. It’s crunchy and doesn’t get all mushy when you cook. I’ve never had anybody complain. Southern hominy, if you buy it in the can, it’s soft and you can mash it. My father loved it. He would fry it up all the time. I never warmed to it, but then one time, Antonio Lopez made chicken posole for lunch. I thought, "This is fantastic." It had the hominy in the soup. The Mexican [hominy], it’s treated and prepared a little differently. I don’t know anything about the preparation of commercial hominy, but it’s different. It has a little bit different flavor, too. It tastes more like tortilla, and you have to chew it. That was just an improvement to me, and so I switched at once.

Tom: What other recent influences on Southern cooking can you tell me about?

Bill: The tolerance for hot, for spicy. You always put hot pepper vinegar on collards and stuff, but now, people have come to crave, I think, a spiciness they once didn’t. That’s probably the main thing. There are other kinds of peppers around now, because we have all these farmers and stuff who are always trying things out. We have Mexican people who want to buy other kinds of stuff, so there’s more stuff to choose from. We’re making salsa in the kitchen. Ricardo makes it. It’s made by scorching things on the grill. He goes down to the bodega and buys all these other kinds of peppers and throws those on. It’s probably the most sophisticated thing in the kitchen, honestly. It’s so good, you can’t believe it. It doesn’t look very promising when he’s making it, because everything’s all black. He throws tomato slices on the grill, and they get all charred. Then, he dusts all that off and grinds it up and it makes this fabulous sauce. I often use it on things that aren’t Mexican.

“I was never ashamed of it.”

Tom: I think a big part of your story is growing up gay Down East in the 1950s.

Bill: I suppose. It wasn’t the problem it was for some people. I knew I was different, but I was sort of eccentric, generally. It wasn’t something I dwelt on. I wasn’t even aware what gay was, honestly. My mother took me aside one day, and she’d tell me that one of my uncles was gay and she didn’t say why I needed to know that. It was an odd, odd thing. She just said, “You need to know this.”

Even then, I didn’t feel like it applied to me. I don’t know, people ask you this question a lot, and looking back you think, “OK, I really always knew that I was, but I didn’t know what it was.” Even when you were little you had some idea, but you didn’t know what it was. You just knew something was up. I was also raised to be very self-reliant and to look after myself, and because of that I never took any crap. I didn’t preach, but I didn’t take any crap.

The only reason I ever really decided to make a big deal about coming out at all was because these women kept falling in love with me! I kept hurting their feelings and stuff, and that was terrible. It wasn’t like this big giant crisis to me — again, I was raised to look out for myself — so I had an advantage that a lot of people don’t have, and I never really cared what people thought so much, either. A lot of that was probably luck, that nobody tried to beat me up or anything because of it. Anyways, my past was a little different than a lot of people’s, I think.

I never was ashamed of it. I lived in a big house full of friends, and I showed up with a boyfriend, and I sat them all down and said, "We’re a couple,” and they all said, "Sure, who cares?" And they were great. They lived in Chapel Hill, so, of course, they acted like that. Once that happened to me, I never sweated it again, honestly. I never really came out to my parents verbally, but I came home with a boyfriend, and they said, "Oh, whatever," which is a little interesting, but it was never a big deal. My brother is gay also. Robert has had a boyfriend for 20 years, and he was worried about talking to my parents. I said, "You know, I don’t think you need to do it. Just bring him home." Don’t say who he is and just see what Mom says. It was fine. It was absolutely fine.

Tom: That’s very fortunate indeed.

Bill: It’s real fortunate. Now, we don’t talk about our private lives in our family at all. That goes back a lot, because the grandparents were that way, too. We don’t examine one another or each other in front of the others, so that leaves room there to not stir anything up.

“There was a big honeysuckle bush. You remember it? Over by the blue house in the parking lot?”

Tom: When did you cross the gap to creating dishes and what was that process like for you?

Bill: Oh, lord, it was a very gradual thing. There wasn’t like one day when I said, "OK, from now on, you’re going to make stuff up." I think there’s a certain logic to coming up with dishes, and I think if you’re observant, it just occurs to you when it should. It wasn’t like, "OK, now I’m a chef. I have to do this." It’s just that certain things make sense, so that’s when you do them.

Tom: Do you remember an early dish that you just sort of extemporized that worked really well and was unique to you?

Bill: There’s been so many, but honestly, a lot of them are really derivative. I think more than anything, is it comes in the form of pleasant surprises. You think, "I wonder if this will work." That’s more how it comes to me. The one I was thinking about was that Green Tabasco Chicken. I just had a garden, and we had too many peppers. That was the only thing that flourished; everything else was a disaster. We had all these peppers, and we put them in vinegar, and we were using that to cook chicken with. Then, Tabasco came out with a green Tabasco in a bottle, and I switched to that at work, remembering the chicken cooked with the pepper vinegar, and it was fabulous. I sort of invented that, but I sort of didn’t. I didn’t invent green Tabasco, but I thought of putting it on some chicken. That’s one of our most popular dishes, so that’s sort of the process that led to that.

GREEN TABASCO CHICKEN

In the words of Bill Smith

It’s the whole chicken. You wash the whole chicken, put a lemon and a jalapeno and a couple of cloves of garlic in the cavity, then you truss it up, and then you paint it — just drench it — in green Tabasco, and you roast it starting at a high temperature, like 400 degrees, until you hear it sizzle. So, in the oven about 20 minutes maybe. And then you turn it down a little bit, and then you baste it with butter. Then, when it’s really done (I like it to be well done generally, and not falling to pieces), you take it out of the oven, you shake more Tabasco over it, and then you use a pan juices to make its sauce. It’s delicious.

Tom: Was Honeysuckle Sorbet a similar surprise, a happy accident?

Bill: There was a big honeysuckle bush. Do you remember it? Over by the blue house in the parking lot? It has to do with that novel “The Leopard” by [Giuseppe Tomasi di] Lampedusa. I was reading this cookbook that kept referencing him. There was a brief reference in this book to a Jasmine Ice that the Saracens had made when they were in Sicily. I tracked that down.

I had tried once before to cook the flowers to make sorbet, and that just wrecks them — you can’t apply any heat to them at all. Anyways, this reference for the Jasmine Ice in Sicily told you to put your flowers in cool water and let them sit overnight. Then, I did that with honeysuckle flowers, and then the next day, when we made sorbet out of it, it was a eureka moment, it was like, "Oh, my god, this is fabulous!" That’s it, and of course I never would write down what I had done, and so every year I had to think and remember again how to do it. Finally, when I wrote my first cookbook, I had to write the recipes down.

Tom: The visual for me is very much of place, and I see you on the bike path in Carrboro, taking advantage of the mound of honeysuckle growing along the fence.

Bill: I do it all the time. Still do that. I take a couple of beers out and a big pitcher. I fill up a pitcher and drink beer. I do it once the kitchen gets going, before it gets too late, but after it’s gotten cooled down a little bit. Then, I go out there, and in half an hour you can get lots of flowers. Also, now we have to make so much of it. We’ve served over 700 serving glasses this summer.

I hired the wives of several of my cooks, and I taught them how to pick the flowers and how to treat them and all that stuff. They bring them to me, and then I pay them and their children to bring them to me, too, because I couldn’t do it all. I don’t have enough time to pick enough. You only want flowers, that’s the main thing. You don’t want any leaves or stems or vines or the rest of it. You sort of pat them down, but you don’t smash them. You need eight cups — that is the least amount that’s worth doing. I pay them $15 for eight cups, and they think I’m crazy – “Are you crazy? They’re weeds, what are you doing?” Anyway, they bring them to me all during the season, and I just stack them in the walk-in and water them, and the next morning I make however much I have.

Tom: What is the season? How long?

Bill: Every year it’s absolutely different, but usually, the end of April or the beginning of May is when it begins. Then, depending on many, many factors, it lasts all summer or it lasts for five minutes. Last winter, it was very cold, and they bloomed late, and every kind [of honeysuckle] bloomed at once. But this summer was sort of medium. We had enough rain, and it didn’t get too hot too early, and so it was pretty good season. There are many varieties of honeysuckle that work, and the ideal season is when the first ones start blooming in May, and then the next ones come into bloom, and then the next one. There’s all sizes of flowers, and they behave differently. Some are easy to pick, some are hard to pick. They taste essentially the same, but the structure of the plant is a little different. I believe that I’m the expert, at this point, on honeysuckles.

There was one year when we got zero. We got five flowers, and I had to hide it in the kitchen. If people asked for it, maybe they could have some. But we’ve only had one year like that. It was a very cold, wet spring, and they didn’t like it at all. They just didn’t flourish. People get really infantile about it, too. They get real mad because they can’t come in and have it.

Tom: Well you know they’ve been waiting all year. I mean, it’s a thing.

Bill: Well, I know, but that’s just the way the world works. Sometimes you don’t get what you want.

On having a hit and getting on with it.

Tom: When I came to Crook’s, it was ’89 or ’90. Obviously, Bill Neal was still alive and hired me. Even then, he was fighting his own success, in a way. Shrimp and Grits was the greatest thing in the world, and people were already coming back to Crook’s because they wanted things to be done the same way and they wanted the same experience that they had the last time. They wanted to sit on the patio and have this certain dish done a certain way and that’s just how it had to be. But creative people don’t really do that. You’re not creative once and then go, "OK, I’m done."

Bill: No, no. You’re right. But you have to, with things like that, like that stupid pie that I make now, that Atlantic Beach Pie — I can never take that off the menu.

Tom: Is that what is says on the menu? "Stupid Pie?”

Bill: That’s what I call it. It is good. There’s nothing wrong with it. It’s delicious. It’s very easy to make, thank God. But it’s just one of those things. I’m not going to take that off the menu, ever. People want that when they come. It’s easy to do. It’s no problem. I don’t resent it. I’m just baffled by it, honestly, but that’s fine. They can have that if they want to, but if they want something else, we’ll have both.

I would never take Shrimp and Grits off the menu either, of course. A lot of those things that people really want stay on, and the rest of the stuff rotates in and out. I can’t take the banana pudding off the menu, ever. I put that on when I came, and from time to time, people would get really mad if it wasn’t on, so I put it on for good. That’s fine.

In a way, that little bit of a skeleton menu gives you some relief from having to come up with something new constantly, which would probably finish me off. If I had to come up with something different for all those favorites every day, I don’t know what I’d do. It’s really doing me a favor. I don’t care. It doesn’t make me mad that people like it. I’m glad if people come in and find things that they like. My creative drive is somewhat changed, I guess. I don’t feel the need to throw a new thing out every day.

Tom: Tell me more about the pie.

Bill: I call it Atlantic Beach Pie. It never had a name, I don’t think. Here’s what happened: I’m in the Southern Foodways Alliance. They were having a field trip to eastern North Carolina, mainly just to investigate barbecue. There were a couple hundred people. We do these field trips every summer. They’re really fun. They can be anywhere. This year, we were in Nashville. Year before that, I don’t remember. Jackson, Mississippi. It could be anywhere. They came to eastern North Carolina, and I’m from down there and they say, "Why don’t you do dinner one night that isn’t barbecue?" I was trying to think of the things I wanted to do. Hard Crab Stew is one of the things that came to mind. Corned ham was one thing that came to mind – they are real typical of that area and nowhere else.

Then, there’s this pie. When we were growing up, we were told that you shouldn’t have desserts after seafood because you’d be sick. You just believed it because your grandmother told you. We were Catholic, so we had seafood every Friday, so we never had any dessert. The one exception was citrus. You could have lemon, so all the restaurants — this was like a folkloric thing all along eastern North Carolina — all the seafood restaurants along the coast had these lemon pies because that was okay to eat. They varied from place to place, but they had a cracker crust. Some people used Captain’s Wafers. Some people used saltines. Some people used Ritz crackers. It was a tug-of-war about what was the best.

I said, "Oh, yeah. That pie. That pie." I did a little bit of research. I went online. I found some old church cookbooks and found a couple of variations of it, and I put this recipe together out of all that — and from memory of this pie that we always had growing up. I hadn’t had it in years and years and years. When it crossed my mind, I thought, “I ought to make that one day,” but I never did. I said, "This would be perfect for this dinner." It was really good, and it’s pretty easy to make. I thought, "OK, I’ll put it on the menu at Crook’s. It’s really easy and delicious and people like it." I did that, and then Katie Workman came in one night, and she does some stuff with food recipes on [NPR’s] “All Things Considered.” She just about had a stroke over it, it’s so good. She said, "I’m going to do an article on it. We’re going to do a piece on it for ‘All Things Considered.’" She did, and the rest is history. You hear about things going viral: It did. If you Google it now, you get like 15 pages about it. It makes no sense. It’s good, but I don’t know why that’s the thing of all the things, but there it is.

Tom: Is it like an icebox or a chess pie?

Bill: No, you bake it.

Tom: What’s it a relative of?

Bill: Well, I guess Key Lime, because it uses condensed milk. My thought is (as I have no proof of this) is that a lot of people along the coast had no electricity, and so they had to use canned milk because they didn’t have refrigerators. You see it in a lot of things in a lot of places you wouldn’t expect it, canned milk. I’m thinking that’s its derivation, but I’ve never honestly investigated its history.

Condensed milk, citrus juice and egg yolks make up the filling, and then the crust is butter and crackers and a little bit of sugar. I use saltines, just because when I decided to do it for that group, that’s what I decided to use. I didn’t experiment around or anything. I like saltines.

Tom: Does it resemble what you had when you were a kid? It must.

Bill: I don’t remember even now. I don’t know. Probably. It was so long ago. To my memory, yes, but I should go down there and buy one somewhere else and see what theirs is like, but I just never got around to it. There’s no altering it now. Even Martha Stewart’s doing it. Like I said, it’s really easy, so if you’re going to have to make a million of something, at least it’s something easy.

I should hush.

Bill Smith’s Dinner Party

I asked Bill to compile a list of invitees to a dinner party – any person, living or dead, besides Jesus and Hitler (as per mutual agreement). His response says as much about the host as it does the guests: a socially and emotionally conscious group of writers, poets, politicians, and a pop star. As Bill declined to put them in a particular order, they are presented here alphabetically.

David Bowie (1947-2016) – The late and lamented androgyne. Bowie made music that should have been popular, and occasionally was. A master of both style and substance.

“I want at the moment to be known as a Generalist rather than as a singer or a composer or an actor. I think a Generalist is a very good occupation to have.”

Colette (1873-1854) – Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette was also a mime, as well as an actor, journalist and novelist, nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1948.

“If I can’t have too many truffles, I’ll do without truffles.”

Elizabeth David (1913-1992) — English cookery author, responsible for helping to revitalize the art of home cooking and an interest in Mediterranean cuisine.

“Every day holds the possibility of a miracle.”

George Eliot (neé Mary Ann Evans, 1819 – 1880) – An English novelist and poet, Evans wrote under a male pseudonym to avoid gender-based typecasting, and scandalously lived with her lover, a fellow writer, for 20 years.

“One can say everything best over a meal.”

Benito Juarez (1806-1872) – A five term president of Mexico, Juarez was born to Zapotec parents, “Indians of the original race of the country.” He expelled the French, overthrew the Second Empire, and restored the Republic.

“Among individuals, as among nations, respect for the rights of others is peace.”

Jhumpa Lahiri (b. 1967) – An American author of Indian descent, Lahiri is a member of the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities as well as a professor of creative writing at Princeton University.

“Still, there are times I am bewildered by each mile I have traveled, each meal I have eaten, each person I have known, each room in which I have slept. As ordinary as it all appears, there are times when it is beyond my imagination.”

Nelson Mandela (1918-2013) – The face of apartheid resistance and president of South Africa from 1994 to 1999, Mandela was also the recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize.

“As we let our own light shine, we unconsciously give other people permission to do the same.”

Gabriel Garcia Marquez (1927-2014) – A Colombian author of extraordinary gifts, Marquez is seen as the father of “magical realism.” He is most famous for his novel “One Hundred Years of Solitude.”

“My heart has more rooms in it than a whorehouse.”

Natasha Trethewey (b. 1966) – A Mississippi native of mixed parentage, Trethewey was appointed United States Poet Laureate in 2012. She is also Poet Laureate of her home state.

“For a long time, I’ve been interested in cultural memory and historical erasure.”

Anthony Trollope (1815-1882) – A prolific, and successful, Victorian novelist, Trollope produced many works about the imaginary county of Barsetshire. Henry James said of him that his “great, his inestimable, merit was a complete appreciation of the usual.”

“Don’t let love interfere with your appetite. It never does with mine.”

If you ask Bill Smith what Southern cooking is, the answer isn’t about food.

Tom: Lastly, let’s tackle the biggest subject of all, which is Southern cooking, Southern food. Everybody probably wants you to enlighten them. Is this the standard question you get asked?

Bill: I don’t know if it’s definable. Obviously, it’s so varied. You go from Louisiana to Charleston to Eastern North Carolina to Tidewater, Virginia, to Southern Florida, then to Texas! They’re all kinds of Southern food and Southern cooking.

Tom: Is it too broad a term?

Bill: No, it isn’t, actually, because ... there’s something in common in the dinner table. It’s more than just sit down and eat: It’s sort of the nexus of our culture. That’s true in all of those places that I just named. It’s just that the food is different at each table, perhaps, but ... maybe that’s true in all cultures, I don’t know, but it certainly is true in this part of the world. The whole ritual of sitting down with Southern food, it’s more than just the cooking of it — it’s the whole deal. That’s important, and it’s the heart of things.

It’s funny, because when I think of Southern cooking, I often think of Southern literature. Too. It is a genre everyone sort of agrees exists. Maybe there’s Midwestern cooking and Midwestern writing, but you don’t hear much about it. Some cultures produce these things, and some cultures don’t, I guess.

[Southern cooking is] approached with earnestness, and everyone that does it wants it to be the best that they can. I think that’s the way one approaches art, generally. There’s a craft and skill involved in it that makes things turn out better. I do see it as art, but I don’t think of myself as some sort of snooty artist or anything. I have to draw the line there.

Tom: Well, no, I can go ahead and call you an artist.

Bill: I don’t know if I ever am or not. Maybe I am, some days.

Tom: What are some of the fundamental skill sets of Southern cooking?

Bill: Well, the family I came from, nobody measured anything. I think that’s a skill you develop. I don’t measure anything anymore, either, except when I’m baking. You have to be exact in picking out your ingredients. That’s a skill set you certainly need. You have to be able to make do with what you have at the same time. If your ingredients aren’t what they ought to be, you can still feed somebody with it. You have to be sort of clever in that regard.

You have to learn how to not be wasteful. That’s a big thing, at least when I was growing up. Everybody that cooked for me came from the Depression, and you had to not waste a speck of anything. If nothing else, it can go into the stockpot. All your onion peels and all that kind of stuff. I used to always save all that stuff, and it always goes into the stockpot.