Down at the Sweetheart Rink

On Oct. 3, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans will open an exhibition of photographs that capture the rural South at a pivotal moment of cultural change. This is the story of the man who shot those pictures — and how they almost never saw the light of day.

Photos by Bill Yates | Story by Chuck Reece

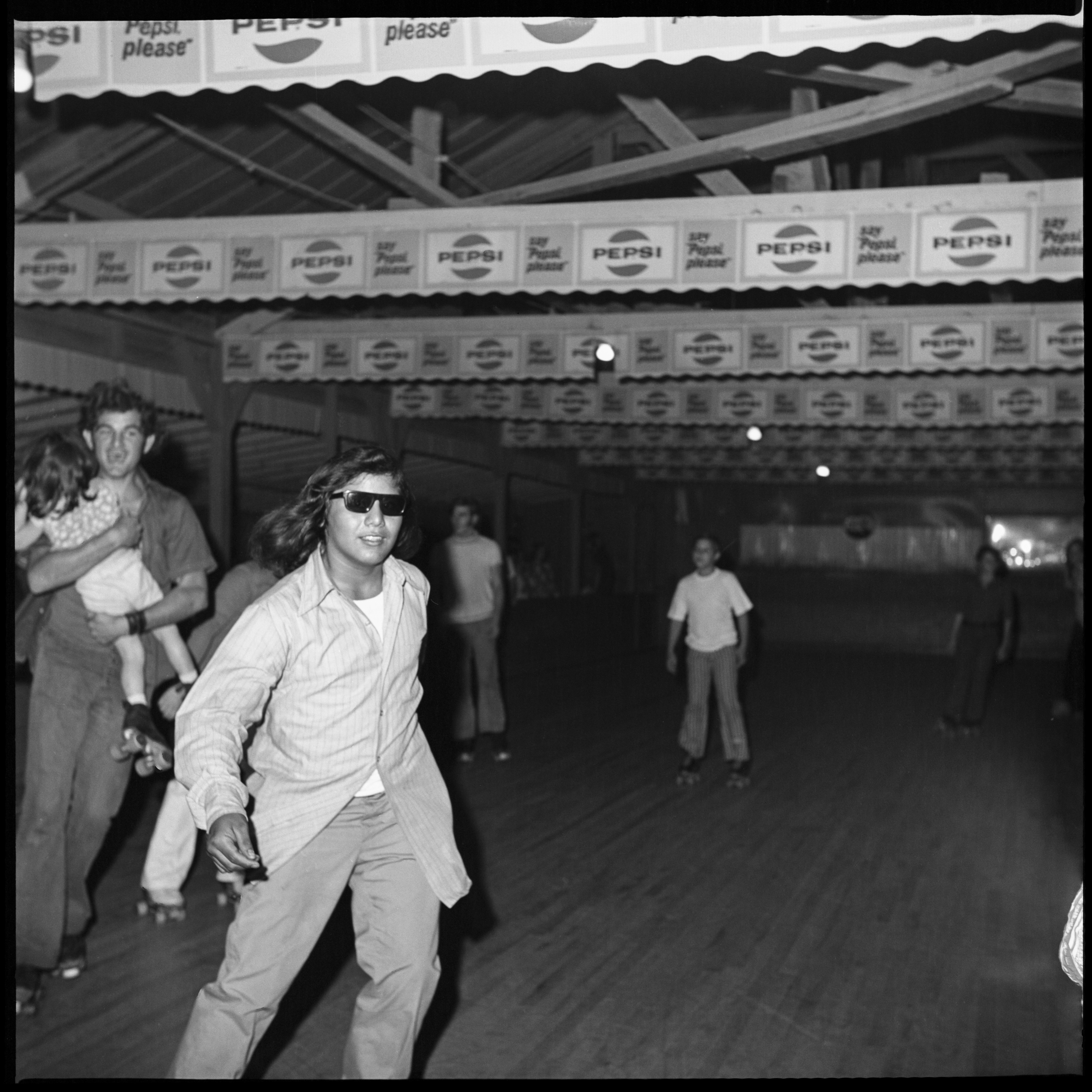

Bill Yates was 26 years old the first time he saw Sweetheart Roller Skating. It was autumn of 1972, and after a stint in the U.S. Navy, the Jacksonville, Florida, native was finishing up his final year of college at the University of South Florida in Tampa. He was studying photography. A few months earlier, in the summer, he had taken a one-week workshop with the late Garry Winogrand, a New York street photographer whose images had gobsmacked the art world in the 1960s.

“I had just purchased a medium-format, twin-lens camera, and, as usual, I was out riding around looking for something to shoot,” he says. Sweetheart Roller Skating caught his eye. The Sweetheart was in a distinctly rural area of Hillsborough County called Six Mile Creek, beyond the Palm River east of downtown Tampa. Old Florida was still Old Florida then. Disney World had opened only a year earlier and had barely begun its transformation of Central Florida.

“The owner was just driving up,” he recalls. “‘Mind if I shoot some pics?’ I asked. He said, ‘Sure, but if you want some good ones, come back tonight — this place will be jumpin'.’" He took his Mamiya C330, a Honeywell Strobonar flash, and eight rolls of Tri-X 220 black-and-white film. He shot every roll.

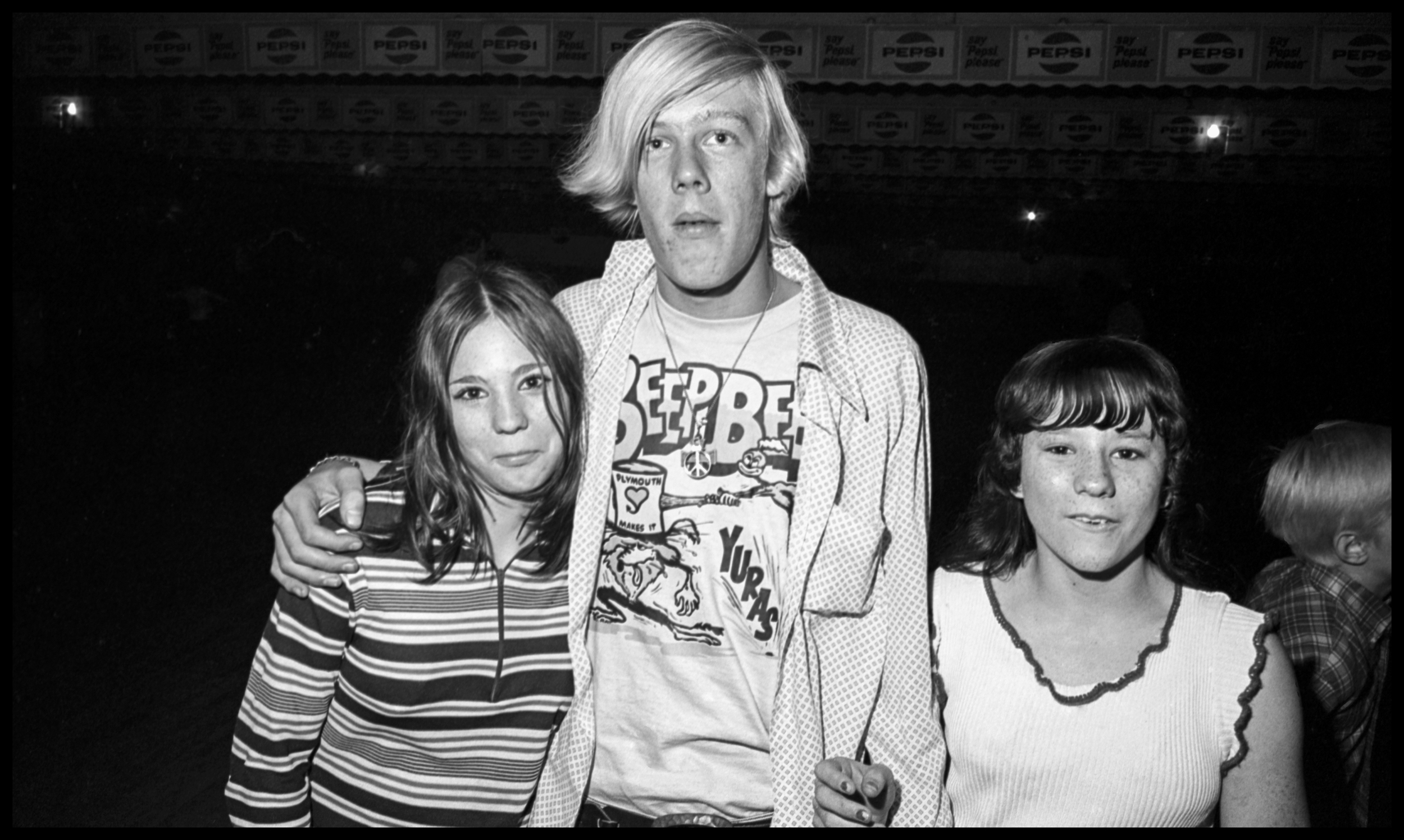

The next weekend, he came back not only with his camera but also proof sheets of his first week’s photographs. He stapled them to the wooden walls of the rink, so his subjects — the teenage habitues of the Sweetheart — could see themselves.

“All of a sudden, I was their newest best friend,” Yates says. “They also saw that I wasn’t compromising them or trying to catch them in moments that were … indelicate, shall we say? Some of them hammed it up for the camera. Some of them were just deadpan. After a while I became like wallpaper. I was there, but I wasn’t. They just went on about their business. Over time, there came a level of trust. I just kind of entered their world, and they knew I was around and gave me full carte blanche.”

By the spring of 1973, Yates had more than 800 images of the kids of the Sweetheart. They were strong enough to gain him admission to the graduate photography program at the Rhode Island School of Design, where he studied under giants of American photography such as Aaron Siskind and Harry Callahan. But at RISD, Yates says, he was encouraged to “start from scratch.”

The Sweetheart negatives and proof sheets went into a box. And there they stayed for more than 30 years. But a few years ago, Yates decided to reconsider his 40 years behind the lens. He resurrected the Sweetheart photographs, and an unlikely chain of events began to unfold — one that has taken Yates and his family from a photo show in a backstage hallway of Jacksonville's Five Points Theatre to his first solo show in a major museum in 40 years.

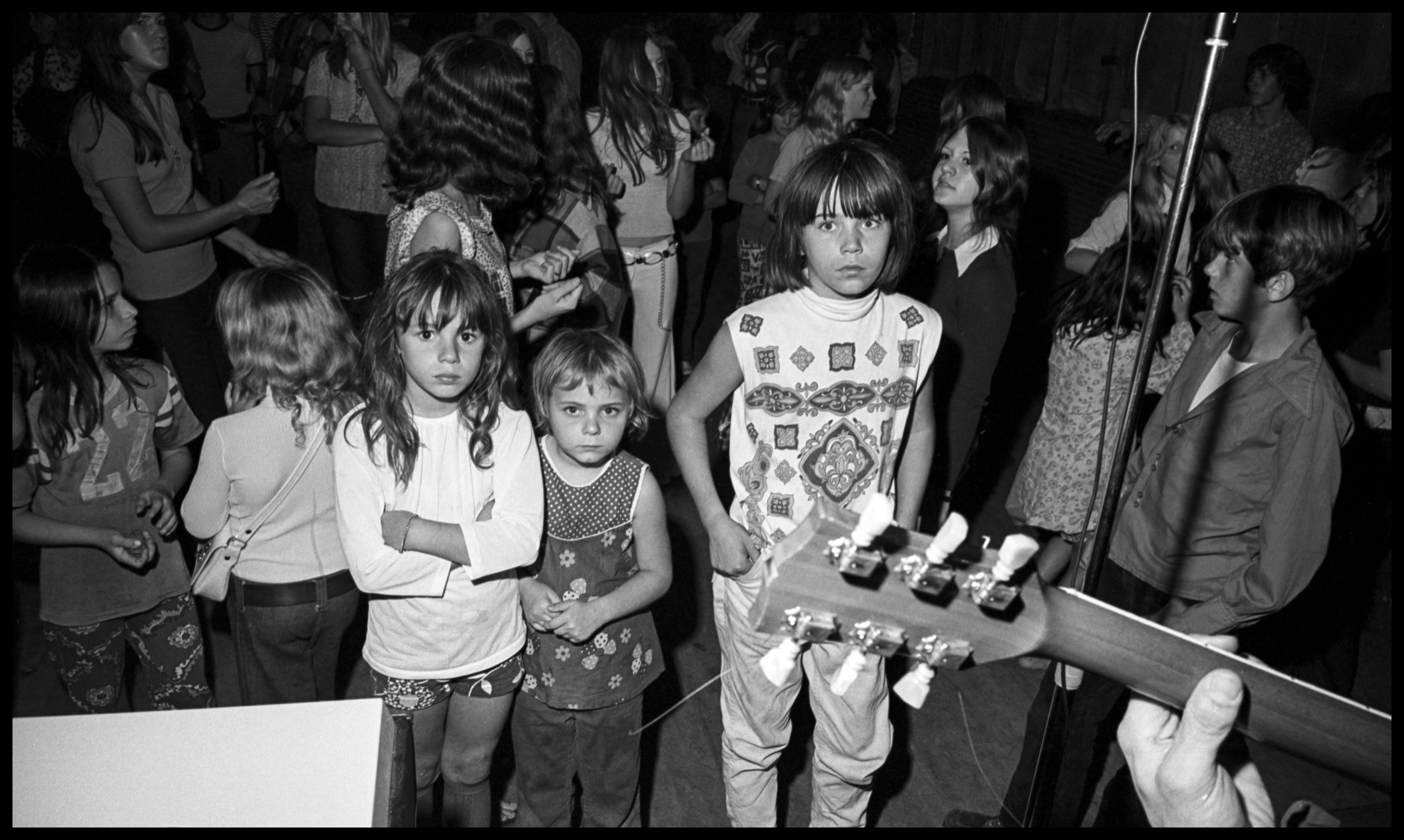

On Oct. 3, New Orleans’ Ogden Museum of Southern Art will open “Bill Yates: Sweetheart Roller Skating Rink.” And the world will get to see a remarkable collection of photographs that document a deep inflection point in our history — that time when the social upheaval of the 1960s became widespread enough to change the lives and attitudes of even rural kids in South.

Life’s Two-by-Fours

Yates was successful as a graduate student at RISD.

In 1975, his work caught the eye of curator Jane Livingston, who had recently left her job as curator of 20th century art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to become the associate director and chief curator at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington. Livingston, who gained fame in 1989 as the curator who resigned rather than remove sexually explicit photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe from the Corcoran’s walls, gave Yates a solo show.

He wasn’t even 30 years old. It was a hell of a start for an aspiring photographer, particularly in the mid-1970s, when photography was just beginning to gain acceptance in the art world as a form equal to painting and sculpture.

Of course, as these stories usually go, his early acceptance into the upper reaches of the art world did not translate into vast wealth and fame.

“Life slaps you upside the head,” he says, “and usually it’s a two-by-four.”

Yates got two whacks in rapid succession, losing his father in 1978 and then his mother in 1979. An only child, Yates had to deal with the loss and all the estate issues that must be cleaned up in the wake of a death.

“I didn’t even pick up a camera for about a year,” he says. “But what got me going again was picking up a camera and starting to travel.”

During that time, he met the woman who has been his wife for almost 33 years, Chrys. He was offered a job as a gallery director at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, and they moved west, got married and began a family. After seven years in Las Cruces, they returned to Yates’ childhood hometown of Jacksonville, where they’ve been ever since. For many years, Yates made a living with work as an aerial photographer.

But after he passed age 60, Yates says, “I got this burr under my saddle to get back to my own personal work and make some sense out of 40 years of shooting.” The entire Yates family — Bill and Chrys and their children Calder and Micaela — is prone to conversation about the arts. Chrys directs the Center for Humanities in Medicine, which integrates the arts into patient therapy, at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Calder works as a curator, writer and artist, and Micaela, like her mom, is pursuing a career where the arts merge with medicine.

All the Yateses had seen Bill’s proofs of the Sweetheart roller rink, so when he began to complain of the burr beneath his saddle, they suggested he revisit that project first. So Yates began the slow process of reviewing, scanning and digitizing more than 700 2¼-inch-square negatives from his year at the Sweetheart. Eventually, he narrowed the project down to a much smaller set of images and printed them.

“I had a studio space in the Five Points area of Jacksonville, and there was a backstage hallway from the street,” Yates says. “It was about eight feet wide and about 45 or 50 feet long. We got permission to turn that into a gallery.”

Chrys and Calder Yates curated a show of the Sweetheart photographs in that hallway in 2009. It proved quite popular in Jacksonville. Then in 2013 Yates submitted the Sweetheart project to Critical Mass, an annual, juried photo competition run by Photolucida, a nonprofit arts organization in Portland, Oregon. Jurors from around the country choose to honor 50 projects from more than 1,000 submissions every year.

Yates made the top 50. And one of the jurors who put him there was Richard McCabe, the curator of photography at the Ogden Museum.

Rock and Roll in the Orange Groves

McCabe knew nothing of Yates’ work, nor of his mid-’70s success in the art world.

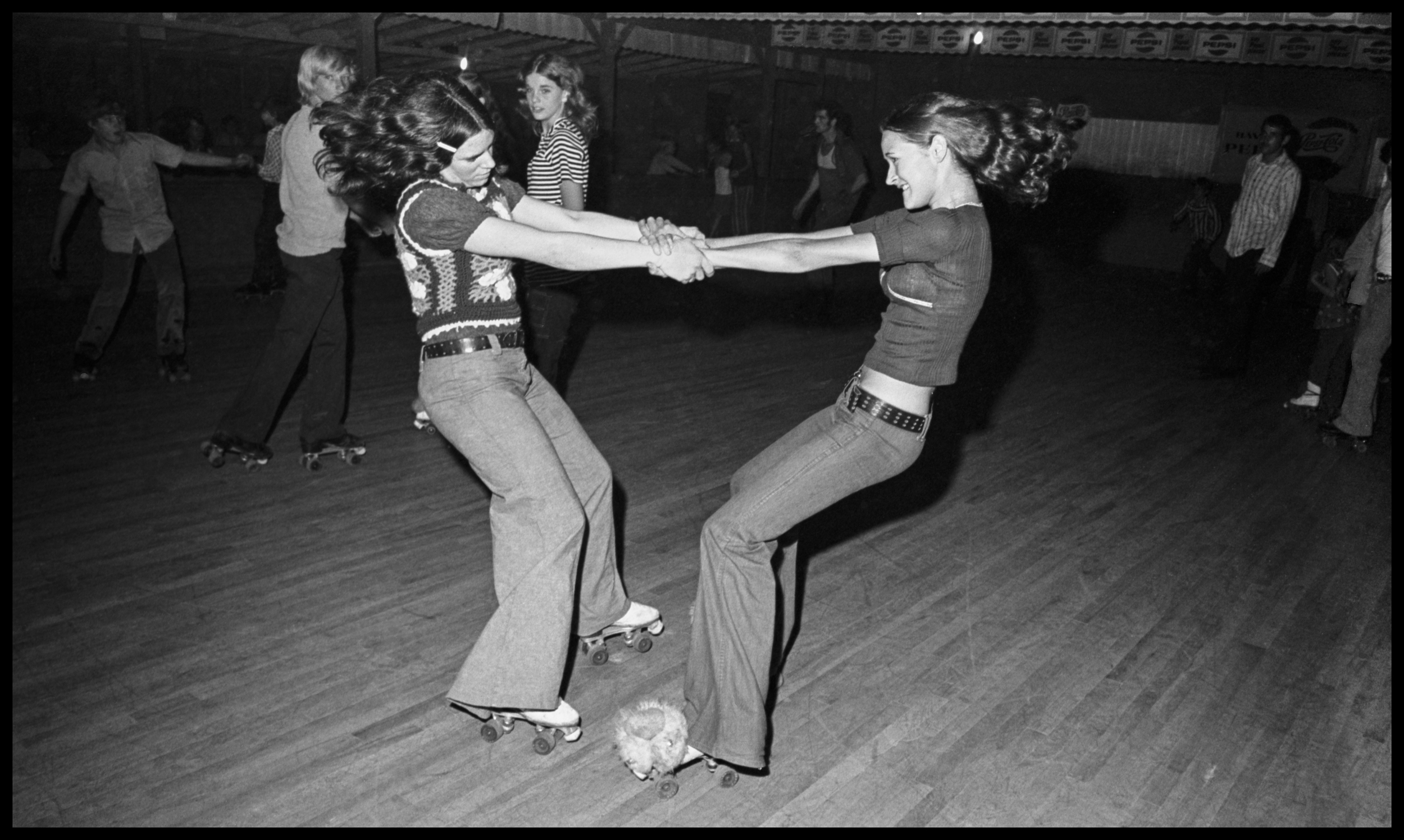

But when he saw the Sweetheart photos during the Critical Mass review, “it just really stood out,” he says. “For one, it was older work — from a different era. But I also thought they were just so weird and so fun. My parents are from 20 miles away from where (the Sweetheart was). I remembered seeing people like those when we would go down there in the 1970s. It was all rock and roll and muscle cars out in the orange groves.”

McCabe says he knew the importance of the skating rink in the rural South from his own youth in Alabama.

“That was big time, going to the skating rink,” he says. “It was a rite of passage. You might skate with a girl or kiss your first girl.”

But more importantly, McCabe says, Yates’ photographs constitute “an almost-lost body of work” that is highly representative of a key moment in the development of photography as an art form.

“Bill was obviously influenced by Garry Winogrand,” he says, “in that he seems to be shooting the second after the defining moment. The way he used flash reminds me of Diane Arbus. His work also reminds me of the way she was exploring subcultures and subsets of society. It’s street photography, but taken inside, in a skating rink. It works on so many levels.”

One of those levels, McCabe says, is about Southern history.

“He caught Florida at this transitional period, a year after Disney World opened,” McCabe says. “That was the last gasp of the old Florida.”

To my eyes, Yates’ photographs speak to a moment in the South’s history I lived through myself, a period when the youthful rebelliousness of the 1960s finally began to shift the attitudes of kids in the rural South.

“This was 1972 and ’73,” Yates says. “You had the Women’s Movement and the Civil Rights movement. You had Vietnam raging. You had the hippies. You had sex, drugs and rock and roll. Music was changing dramatically. All that stuff from California had moved east.”

Look at the Sweetheart photographs, and you can see the truth of Yates’ words in the eyes and stances of their young subjects.

“You could see it by their appearance,” he says, “by what they wore, their expression of sexuality, their newfound freedoms to do and be and dress up the way they wanted to, rather than in the more conservative way.”

When the right photographer with the right eye is in the right place at the right time, the world gets iconic images — perfect expressions of moments in history, as societies or regions move into uncharted territory.

That’s what Bill Yates’ photographs from 1972 and ’73 achieve. They’re that good. And it seems only right those photographs are bringing Yates back into the spotlight of a major museum once again — after 40 years of life and the two-by-fours it whacked him with.