A Carolina Dog

He got Penny for Christmas. He didn’t know he would get a trip into the deepest reaches of the 14,000-year history of dogs in North America.

Things we love in the South: Moon Pies, SEC football, Otis Redding, Flannery O’Connor, Cheerwine and, probably more than anything else, our dogs.

What is it about Southerners and our dogs?

Maybe it's because in the South, we're a bit more country than our cousins to the north. Perhaps we are a generation or two fewer removed from the time when having a dog was essential to surviving and living off the land. Our four-legged brethren are a bridge between that wild past and a civilized present. We take them into the woods with us and let them sniff out our game and then retrieve it for us. We train them to protect our property. And they do this in exchange for a warm place to sleep, a full belly and the love of a human family.

We love dogs because they were shaped by us and their history runs concurrently with ours. They're a part of our heritage. The Plott Hound was brought to North Carolina from Germany in the 18th century to hunt wild boars. The Redbone Coonhound was brought to the South by Scottish immigrants, then selectively bred by Southerners to create a dog with amazing stamina and tenacity. The Catahoula Leopard Dog is theorized to have been first bred in 16th century Louisiana — a cross between the Native Americans' dogs and Fernando de Soto's Greyhounds. These dogs were bred by Southerners to thrive in the South. They typify our love affair with man's best friend.

But you may have never heard of the most Southern dog alive.

This dog's ancient bloodlines were never altered by humans. Its ancestors crossed the Bering Strait with the first humans ever to settle this land — I'm talking about North America, not just the South. These dogs traveled the expanse of this great continent and went as far they could, finally creating a home on the border of Georgia and South Carolina, hidden from human eyes under longleaf pine and in cypress swamp for thousands of years. They scratched and survived and were molded by the land, made by natural selection into the perfect vessel for survival in the wild South. Unlike most dogs, they don't exist because people needed help with a job or wanted a companion. They exist only because Mother Nature decided they earned that right. And a motley crew of folks gathers every year, deep in the South Carolina woods, to help keep these mangy, yellow dogs thriving.

They're called Carolina Dogs — some folks call them Dixie Dingoes — and I have one.

Penny (left) and Mason explore the tall grass and longleaf pines of Belongadon Plantation in Bishopville, S.C.

My father and I were lost on the back roads outside Lavonia, Ga., the day I got Penny.

We set out to visit an animal shelter there, but missed a turn somewhere or another among the lush hills and dense forests of Northeast Georgia. My father never worries when he is lost. He just enjoys the drive.

I wasn’t glad for the time. I felt an itch that needed a scratch and every missed turn made the scratching wait a little longer. As a young Southern man, I saw owning a dog as a rite of passage. Lots of my friends at the University of Georgia — where I was smack in the middle of a five-year plan — owned dogs. Owning a dog would signify that not only was I independent enough to take care of myself, but also that I could also care for another life.

I wanted a dog. I needed a dog.

But I didn’t know I needed a dog until my girlfriend of seven years, Kristen, suggested getting one in November 2011 as a Christmas gift. Kristen and I searched for the perfect dog for a solid month. Each Craigslist ad I looked at and every stop at a shelter made my need for a dog grow. It lived in the pit of my stomach and grew and gnawed until I about lost my mind and was ready to take home the next damn dog I saw.

Thankfully, I never reached that point.

The faded street sign read McGee Road, or it would have if not for years of bombardment by sun and rain. I had never been down this road before, but it looked like almost every road I had ever driven growing up in Northeast Georgia. For stretches of the drive, the woods would contract, tightly flanking both sides of the road before expanding and giving way to large swaths of pasture on top of rolling hills.

The shelter sat on a hillside overlooking a small bog. The water was stagnant. Nothing moved, either on the water’s surface or at the woods’ edge. It gave the same impression that all land around here gives: a silent facade that teems with life once the surface is broken.

A pen full of puppies sat adjacent to the main building. Only a week before Christmas, all 10 or so looked like they would be perfect under anyone’s tree. They looked as good as any puppy I had seen in my month looking for one. This was it.

I will find my dog here.

My dad was with me because Kristen had been emotionally drained from visiting shelters and saying no and saying no and saying no. Every dog she saw, she wanted. You could watch her heart break a bit after each shelter we left empty-handed. She threw in the towel.

“What about this one? She seems like she wouldn’t be too much to handle,” my dad said, motioning toward a ball of fur the same color as the dirt that lined the pen.

Penny leaned against the chain-link fence, quiet as a church mouse, bathing in sunlight. She was stoic. There were no whites in her eyes. She looked forward through almond-shaped pools of deep amber. Her golden fur was warm when I picked her up and held her in my arms. She looked at me and I looked at her and everything about the moment seemed right.

This was my dog. But Kristen had to know it was her dog, too. I took a picture of Penny and a picture of another puppy. I sent them to Kristen and told her to pick. One of these dogs was going home with me, and she could pick which one. If she was going to adopt a dog with me, we had better be on the same wavelength about the one to get. I got a call a few minutes later.

“The yalla one,” Kristen said in the country drawl she had worked years to hide. The twang was a good sign. It came out only when she was drunk, tired or excited, and it was too early in the morning for it to be either of the first two.

So I carried Penny, my Christmas puppy, a gift from the woman I love, back to my dad’s truck and started wondering, for the first time, what breed she was. I had been so wrapped up in the fact that I had a dog, I hadn’t stopped to think about what kind of dog I had.

“What do you think she is?” I asked my dad as we made our way back to truck.

He didn’t pause, look up or break stride.

“She’s just an old yaller dog.”

I spent two years trying to find out exactly what Penny was. What made it more frustrating was that I eventually found out my dad had already given me the right answer.

He just didn’t know it.

Penny takes a rare break from exploring to pose for a few photos. (That's her up in the header image, too.)

So Penny was the Mystery Dog. The first time I took her to the vet, I asked him what breed he thought she was. The animal shelter had listed her as a Labrador/Chow mix. The vet agreed.

Something didn’t sit right with that explanation, though. All of her features have never matched that combination. Her face looks more like a wolf’s than anything else. And a Chow’s tail stays in a permanent corkscrew. Penny’s makes a fishhook. When she’s excited, it perks up, and as she trots along it bobs back and forth, like a metronome keeping time.

But she expresses herself most through her ears. Most of the time they jut out from the side of the head, like a deer. Or Yoda. When she’s alert or investigating, they stand up straight and resemble a German Shepherd or Husky. When she’s tired or excited, she tucks them along her head.

The best part of her ears is their texture. They have a finer fur than the rest of her body. They remind me of the Lamb’s Ear plants my grandma used to grow in her garden. When I was too young to go to school, she’d look after me while my parents worked. She’d work in the garden and talk about her hydrangeas and rhododendrons and chrysanthemums, and I’d sit in the dirt and rub the Lamb’s Ear. I got older, but she always kept some Lamb’s Ear in her garden just for me.

People were never Penny’s strong suit; she’s the suspicious type. It takes time for someone to gain her trust. Lots of time. If someone knocks on my door, she lets loose a blood-curling bay that’ll make you think a possum ran over your grave. The bark is worse than the bite, though, mainly because the bite doesn’t exist.

Any time someone comes to my place, Penny makes sure I know it, and she makes sure they know it, too. We started calling her the alarm dog. There is little need for home security systems or locked doors with Penny. If Penny sees something, the whole neighborhood hears about it.

She has a group of roughly 10 people who she won’t bark at. There’s a more exclusive group — Kristen, my parents and me — whom she actually gets excited to see and goes crazy for. Actually, “goes crazy” may not be an accurate description of Penny’s emotions. She goes over-the-moon, batshit insane.

The excitement comes in stages. First, uncertainty. She hears someone approaching the house and starts quietly barking under her breath. Second, a call to action. The door begins to open, and she throws out that spine-tingling bay. If someone’s breaking into her house, they’re gonna know what they’re getting into first. Third, shock. If it’s one of the few people she knows and loves and trusts, the insanity kicks in. Her knees get weak. She drops to the floor. She then walks toward the door, and her tail starts wagging so hard that it shakes her entire rear end. She bares her teeth in a submissive snarl, an unsuccessful attempt at smiling. Fourth, and finally, joy. She falls to the ground, rolls on her back and exposes her underside, the ultimate sign of submission. She stares me down as if to say, “This belly ain’t gonna scratch itself.” Multiply her excitement by 10 if it’s Kristen at the door and not me.

That’s what always made Penny seem so special to me. I had seen dogs who were attached to their owners. I expected that to happen with Penny and me, but certainly not at the level it has.

Even though she’s a perfect inside dog, she looks like she belongs in the woods. In thick forest, she bobs and weaves between trees. She leaps over large roots and crawls under half-fallen trees and never breaks stride. She’ll crash down the bank of a gulley, make a splash in the water, climb the other, while barely making any noise. The only sound she ever makes in the woods comes from a light crushing of leaves beneath her feet, and if you stand still to try and listen for it, she freezes with you and disappears behind a din of crickets beeping and birds chirping.

I love to take her collar off and let her run through the woods uninhibited. She looks perfect that way. Like she was made for it. Without the jingle of her dog tag, it’s even easier to lose her in the forest. Eventually I’ll catch a glimpse of her standing on a rock or log, ears perked up, chest poked, tail in a perfect fishhook curve. There’s something majestic and primal about it. Wild. She’ll look at me with those amber eyes the same way she did at the animal shelter, then disappear again in a silent flash. When I’m ready to leave, I’ll open my car door, say her name and she will pop out of the woods, almost out of nothingness, and into the passenger seat.

God, what a dog.

Penny in the Carolina Dog's natural habitat.

For a long time there was a guessing game about what exactly Penny had in her. Lots of people thought she was a mutt far enough removed from any purebred parents that she’s now indistinguishable from whatever stock she came from. Some people thought she looked like the wild dog of Australia, a dingo ...

About year after I got Penny, I googled ‘American dingo.’ I can’t remember what exactly drove me to search for it, but I remember what I found. Picture after picture of dogs who all, in some way or another, looked like Penny. Some looked like clones. These dogs had all kinds of names: Carolina Dog, American Dingo, Dixie Dingo, porch dog, and — there it was — “yaller dog.” Dad was right.

I was sucked into a hole, reading descriptions and looking at photos of people’s dogs. I was shocked that behaviors and traits I thought were unique to Penny appeared in most Carolina Dogs. The hooked tail and the almond eyes were present in all of them. The behaviors are what convinced me, though. I always bragged that I never potty-trained Penny. She just learned not to go the bathroom inside within the first two weeks I had her. Ditto for all Carolina Dogs. She would dig small holes in my parents’ front yard to stick her snout in. Ditto again. She was more loyal than any other dog I’d ever been around. Carolina Dogs have an extreme pack mentality.

The more I read the more amazed I became. Carolina Dogs are hypothesized by their discoverer to be the only American dog breed with no European ancestry. All of their forbearers are said to have come across the Bering land bridge with the first humans to inhabit North America. They’re dogs that look and act the way they do because of the natural selection they endured over thousands of years in the South.

I was almost certain Penny was a Carolina Dog, but I wanted proof. So last summer, fresh out of college and after having Penny for more than two years, I went looking for some. For a long time, there was no genetic testing that proves whether a dog is a Carolina. If you wanted to know if you owned a Carolina Dog, there was only one man to talk to.

Dr. I. Lehr Brisbin holds court with some of the breed's finest at the second annual CDHERC Tail-Gate.

I heard the howling before I saw the dogs.

Dr. I. Lehr Brisbin led me from the Hop Spot convenience store in New Ellenton, S.C., to his kennels only a short drive down the road. Per usual, Penny rode shotgun. The short driveway, lined by fence, looped to make a small courtyard in front of two trailers, kennels attached to each. Behind the fences were acres of woods filled with wild dogs.

“Hear that?” Brisbin asked as a wail of siren-esque screeches echoed across the property. Penny’s ears perked as she peered around the grounds for the source of shrieking. “New Guinea Singing Dogs.”

While Brisbin was telling me about his life with Carolina Dogs, Penny paraded around the enclosure where Brisbin kept his. It was the first time she had ever seen another Carolina. She was intrigued.

Bris, as he is known to friends and colleagues, is an older man with white hair and a square jaw. Bris became an expert on dogs — primitive dogs to be more precise — as a former researcher at the University of Georgia’s Savannah River Ecology Lab, which is situated in the U.S. Department of Energy’s Savannah River Site nuclear facility. At his kennels, he keeps Carolina Dogs, Border Collies, and the aforementioned New Guinea Singing Dogs, regarded by many as the rarest breed in the world and noted for the high-pitched bay that gives the dog its name.

But I’m here to talk to Bris about Carolina Dogs, his claim to fame.

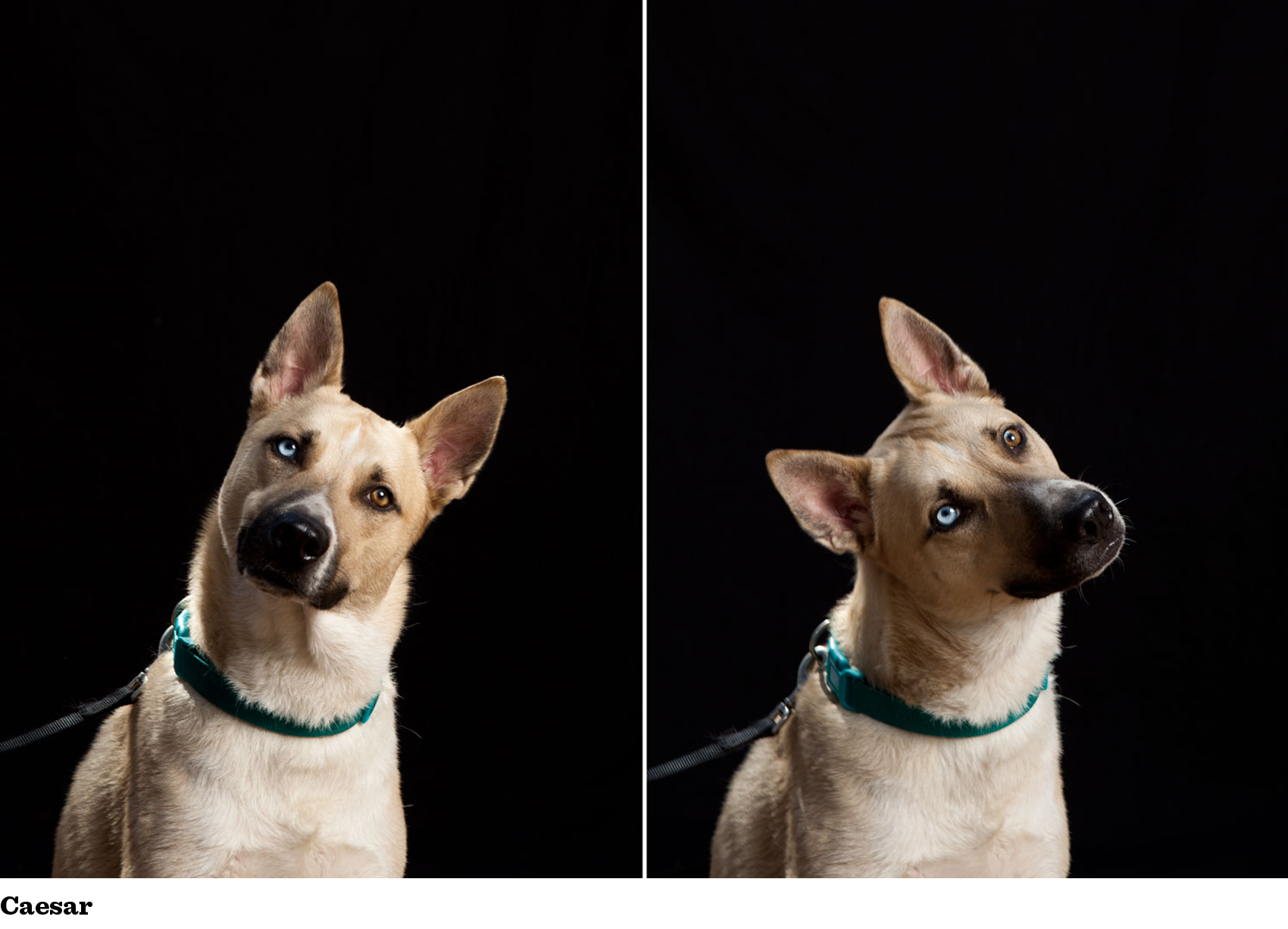

Star, a Carolina who belongs to Pat Watkins of Lake City, Fla.

Bris is an accomplished dog trainer who spent many years showing them in the American Kennel Club. As a young trainer, he primarily worked with Pit Bulls and Bloodhounds. But his interests always shaded more toward the wilder side of nature.

“I wanted to train a wolf or dingo, but couldn’t get my hands on one,” he says.

As a researcher at the SREL, Bris’ job was to wander into the preserve — a point of pride he held over the site’s nuclear physicists, who were cooped up in their offices — to trap and tag the fur-bearing animals. On these trips, he’d frequently see wild dogs on his trips into the field, but he identified them the same way the locals did: porch dogs, yaller dogs. Until a day in 1976 when his ex-wife brought one of those wild strays home and something clicked in Bris’s mind.

“I had a gee-whiz moment,” Bris said. “I looked down at this dog my wife had brought home from the Savannah River site and said, ‘You look like a dingo.’”

That’s when Bris first thought these wild dogs in the swamp along the Georgia-South Carolina border were more than a bunch of mutts.

The history of dogs is convoluted and filled with unproven theories. Indulge me for a moment while I go through a short, hypothetical history of the dog, according to Bris. The first dogs are thought to have originated from wolves somewhere around the Middle East. These were smaller, more docile wolves. The Arabian wolf, Ethiopian wolf and Iranian wolf are suspected to be possibles origins for the first dogs. From there, dogs split into two lines: those developed in Europe and those developed in Asia. The Asian dogs are more primitive and wolf-like.

The line disseminated through Asia, with the dogs following human camps across the continent. Primitive dogs remained in certain places, eventually developing into entirely separate breeds. This line travels through South Asia, leaving dogs like the dhole to inhabit India. At this point the line splits again. One line goes farther south, through Sumatra, Borneo, and New Guinea, where the singing dog is left. The other line went north through China and Korea.

Which brings us to about 14,000 years ago when Carolina Dog-types followed camps of humans across the Bering land bridge and settled in North America. The American wild dog was largely hybridized out of existence in most places where large human populations existed. But in those pockets of land without large populations, namely the rural South, these wild dogs can still be found unhybridized. Bris summarizes it more simply.

“There still exists, in some possibly isolated pockets, within remote pieces of habitat in the United States, dogs that carry many of the morphological, behavioral and socio-ecological traits of the first dogs that came over the Bering land bridge. Rural areas with large expanses of natural habitat is where this dog survives unhybridized.”

Bris became fascinated with the breed. He finally had the wild dogs he always wanted, and he had living among the whole time. With the help of the United Kennel Club, Bris developed a breed standard and stud book, recognized by the UKC in 1995. Bris said dog show judges love Carolinas.

“The judges look at these dogs and say, ‘God, they’re perfect. Their stifles (knees), their feet. Everything about them is perfect.’ And I say, ‘Yeah. That’s what Darwin did, along with 14,000 years of survival of the fittest.’”

As the overseer of the stud book, Bris is the only person who can say whether or not someone owns a Carolina Dog. While Bris and I sat under the shade of a rundown trailer adjacent to the dog pens, Penny in between us, I asked him the question that had toyed with my mind for more than a year since I first searched for ‘American dingo’: Is Penny a Carolina Dog?

Since no DNA tests exist to prove whether a dog is a Carolina or not, Bris rattles off the three criteria for a Carolina Dog: what they look like, where they come from, what their pups look like.

Penny fits the description physically and comes from around Lavonia, near the Georgia-South Carolina line. So she’s good on both of those accounts. But as a dog from an animal shelter, I was required by law to spay Penny, though at the time I still had no idea how special her breed is. With no puppies, we’ll never know for sure if she’s a Carolina Dog.

But Bris said he’d call her one, and that I should, too.

When he found out she was fixed, he was dismayed in a way that seemed familiar to him. Penny would have made a wonderful addition to the captive gene pool since she was probably born in the wild. However, most people with wild-caught Carolina Dogs get them from shelters and only find out what they have years after the dog has been fixed. Penny is one of hundreds of such that Bris has seen.

“She’s got everything going for her, except ovaries,” Bris said.

But, for Bris, the best part of his wild ride with Carolina Dogs is the surprise and excitement that comes with learning something new about them. And that’s both from finding things out about scientific studies that infer Asian ancestry in the DNA of Carolina Dogs, as well as finding a Carolina Dog like Penny.

“I love the surprise of figuring out new stuff, like the proceedings of the Royal Society,” Bris says. “And then the surprise of Penny, an absolutely beautiful Carolina Dog, who is so laid-back and so unconcerned with anything that she is just perfect. What more could you want?”

Chibi (facing camera) and Rabbit, ever watchful, like all good Carolinas.

Sand fills the air around Belongadon Plantation in Bishopville, S.C. Penny caustically looks back at me and Kristen before disappearing over the horizon in a cloud of dust. The dogs bark, howl, run and hunt together, as a pack, at what is likely one of the largest gatherings of Carolina Dogs in one place in the 14,000-year history of these dogs in North America.

Belongadon is owned by Don Anderson and located in the heart of the South Carolina Sandhills, a region which was once the coast of the Atlantic ocean, along the Lynches River. As the ocean receded, the sand was left inland, where it remains today. On Anderson’s 1,000 acres of Sandhills land, he grows longleaf pine trees, the pine trees native to the area but largely wiped out in favor of cotton fields, and sells the straw.

Anderson, a long-time Carolina breeder, was gracious enough to lend out this beautiful land to the Carolina Dog History, Education, Research and Conservation group for its second annual Carolina Dog Tail-Gate: a time when Carolina Dog owners and enthusiasts gather for a weekend of fellowship, drinking and discussion of issues surrounding the breed. It’s also a wonderful opportunity to see a group of 20 to 30 dogs gather in their natural habitat, running in a pack as God intended.

Don Anderson, longtime Carolina Dog breeder and owner of Belongadon Plantation.

The Tail-Gate was organized by the founders of the CDHERC Facebook group, Susanne and Michael Ruano, and Bris’ wife Donna, the web-savvy half of the couple. There were swamp tours, put on by Don’s son Tim, showing some of the land where wild Carolina Dogs have been found, and an unofficial dog show judged by Bris. A pig was cooked. Dogs went leashless for hours on end. A good time, as they say, was had by all.

The most important news from the three-day event was the formation of the Carolina Dog Society of America, a new, official UKC club. The club will hold events, such as the Tail-Gate, and conformation shows for the breed, where only Carolinas are judged on how closely they fit the breed standard. But their most vital role may be as a voice to clear up misinformation surrounding Carolina Dogs. That began with a question and answer session pondside with Bris.

One of the first myths Bris is quick to dispel is that Carolina Dogs are dingoes. Carolina Dogs are just that: dogs. They resemble dingoes due to the niche both fill in the wild, but taxonomically, Carolina Dogs fall under canis familiaris.

Bris also addressed the myth that these are only Southeastern dogs. They have been found in almost every Southeastern state, and as north as Ohio and Pennsylvania. Two camp-goers came from Arizona with a scrapbook filled with photographs of potential Carolina Dogs they’d found in Arizona shelter. The common denominator isn’t Southern, it’s rural. It’s just that in the South, we have a whole bunch of rural.

Bris’s time speaking was one of the few moments during the weekend that wasn’t pure chaos. As people move, their dogs move with them, or with other dogs. It’s constant commotion and movement. But when Bris speaks, all the people stop to listen. And when the people stop, the dogs stop. They nap on their owners’ feet or bask in the sun. Penny’s eyes droop as she fights sleep at Kristen’s side. They are silent.

Silent until a truck driven by Don’s son tops the hillside, engine revving, and sends the entire pack into a frantic spasm of alerts and alarms. It’s the closest representation I think I’ll ever see of dogs playing their ancient roles as camp followers. The camp was threatened by an unknown intruder, so they let their people know.

After that, the dogs dispersed, breaking back into small packs, exploring in the pine trees and sand. The dogs hunted together, using their tails to signal one another in the tall grass. Pack dynamics are strong in Carolina Dogs. It’s how they were able to survive in the wild. The lone-wolf act doesn’t fly with Carolinas. They need one another to ensure the next generation survives.

That pack mentality also builds between owner and dog. Most Carolina Dog owners report a strange bond between them and their dog: one stronger than they thought was possible. There are stories of Carolinas saving their humans from rattlesnakes and sniffing out heart attacks. There is obviously the bond between Kristen, Penny and me.

“The leader leads by commanding loyalty, not fear,” Bris says. “If somebody in the pack fears the leader, they leave the pack. And if it’s a female, there goes [the leader’s] breeding.”

Bishop drinking from a pool in his namesake Bishop, S.C. He was caught in the wild along the Lynches River.

The alpha of the pack at the Tail-Gate was Bishop, named for the very land on which he stood. Bishop was wild-caught on the Lynches River. He looks like a wolf. He stands tall and proud and no one tries to scuffle with him. But you’d never know he’s from the wild. He’s the sweetest dog you’ll meet and perfectly obeys orders from his owner, Mark Eden.

Eden got his first Carolina Dog in the early 2000s. A friend had gotten one from South Carolina and couldn’t take care of it anymore, so Eden took it. Eventually, he discovered his dog was a descendant of Don Anderson’s first Carolina, Tadpole. Although Anderson has direct access to the swamp and land, Eden claims to have the strongest Lynches River bloodline in existence. Anderson used to have a penchant for giving his puppies away to anyone who might want one as soon as they were born. He only used Tadpole to breed with and when Tadpole died unexpectedly, half the line was lost. So Eden used his dog to help restart it.

Anderson waits before adopting out his dogs now.

“If you adopt all your puppies when they’re eight weeks old, you don’t know which one of them will turn into that special, super dog,” Anderson says. “But that’s the good thing about a Carolina Dog. You can get him at any age and he’ll be just as loyal and loving as can be. You can tell that when you adopt one. They adopt good.”

Eden, vice president of the Carolina Dog Society, came to the Tail-Gate from Indiana with his two dogs, Bishop and Dixie. Dixie is a long-haired black and tan, super rare among Carolinas. He breeds specifically for those traits.

Most people at the Tail-Gate are fairly new to the breed, having found out about it only in the last few years. Eden has been involved in the community longer than most and believes that the Carolina Dog Society can help more people understand the breed.

As an old-timer in the community, Eden has seen the role the internet has played in helping people learn about and understand Carolinas. CDHERC has only been on Facebook for a few years, but it has already helped grow the community significantly.

“Fourteen years ago, the Internet wasn’t what it is today,” Eden says. “People are finding out more. There are people who have had a Carolina Dog for 10 years and only became aware because of Facebook. When we put on the Tail-Gate last year, we had 300 members on the Facebook group. By February we had 600, and since February we’ve gone over 1,000.”

Getting the word out to people is what the Carolina Dog Society stresses most. If someone can identify a Carolina Dog before it enters an animal shelter, it is less likely to be “fixed,” which means a more diverse breeding pool and Carolinas for generations to come. Eden is pragmatic about the state of Carolinas in the wild. They’ll be gone sooner or later. Eden figures that just as the Carolinas helped the first humans on this continent survive, we must help them.

“They’re gonna be extinct in the wild sooner or later,” he says. “The breed is how the dog is gonna be carried on, so it’s up to us to be their caretakers.”

Candi Watson holds her Carolina Dog, Coco, one of many her family owns.

Every morning, before I do anything else, I mosey out of bed, groggy-eyed, amble to the door and open it. Penny, having just finished her morning stretches, darts out, no collar. She’s smart enough to stay away from potential danger. She’ll run around, explore, sniff to her heart’s content and push in the cracked door when she’s had her fill of morning adventure. It’s the least I can do for an animal born in the wild.

My three years with Penny have probably been the best of my life. I’ve graduated college, started a career, and Kristen and I have grown even closer. It’s hard to fight with someone when a cute dog is staring you down disapprovingly. I don’t know what my future holds, but I know these two are part of it.

I always say I’ll never own another dog breed. Carolinas are just too interesting to me. I’m invested now. I know how special they are, and I know how important they are to the natural history of America. They are more than a glimpse into our past. They’re a vision of it.

But as much as I love Carolinas, I love Penny more. And I love what she represents: the beginnings of a family for Kristen and me. It really doesn’t matter what breed she is, whether she’s an ancient Carolina Dog or just a mangy, old yaller dog.

We love Penny. She’s our dog.