What We Talk About When We Look at Ourselves

For the last two years, a Columbus, Ga., nonprofit has been building an incredible collection of contemporary Southern photography — not only for the sake of art, but also to provoke discussions among Southerners about our history, our present and our prospects for the future.

Alan Rothschild is bound and determined that I understand the significance of William Christenberry.

It’s the weekend before Thanksgiving, and we are bouncing around Hale County, Ala., in Rothschild’s SUV. As we head into the tiny town of Newbern, which is the home base of Auburn University’s innovative Rural Studio architecture project, Rothschild points out various of the Studio’s landmark structures.

But his real destination is a building much older than any of those. It’s an old green warehouse adjacent to the town’s general store.

Christenberry’s warehouse.

William Christenberry is a renowned photographer, painter and sculptor, who at age 78 still teaches at the Corcoran College of Art and Design in Washington. He returns annually to his native Alabama to photograph the same buildings. One shot per building per year. Galleries and museums display the photographs in groupings that allow the viewer to see the slow decay of these rural structures across the decades.

The most famous of Christenberry’s Alabama subjects is this warehouse. “Green Warehouse, Newbern, Alabama” has become one of the most notable series in the history of American photography — and a revered touchstone for Southern photographers.

“What's beautiful about photography is that it documents a place in time, and it really never changes,” Rothschild tells me. “The greatest example of that is Christenberry's annual journey back here to Hale County.”

The average Joe who drives up Alabama 61 through Newbern would see only an old green barn in the process of falling down. To the collectors who haunt auction houses such as Christie’s, the old warehouse is the subject of photographs for which they will pay thousands of dollars.

But to Alan Rothschild, it represents something far broader: the changing nature of the region he loves, his home, the American South.

Two photographs by William Christenberry. Above, “China Grove Church, Hale County, Alabama, 1979,” and below, “White Door, Near Stewart, Alabama, 1977.”

If you have concluded by now that Rothschild is a photographer or an art professor or a historian, you’re dead wrong. Rothschild is a mild-mannered lawyer for a firm in Columbus, Ga., just across the Chattahoochee River from Alabama. He looks precisely as you would expect him to look. He is middle-aged. He wears rimless spectacles and dresses with scrupulous propriety. He wears suits on workdays, and on weekends, clothing most people would label “business casual.” His hairline appears to be receding at least as fast as the polar glaciers.

He is absolutely the kind of guy you’d hire to be your lawyer (and, full disclosure, Rothschild’s firm helped the BS do its corporate setup). But he is not, at least at first glance, the kind of guy I’d expect to wax rhapsodic and eloquent about the importance of an art form — any art form.

But the Columbus-based nonprofit Rothschild established in 2012, the Do Good Fund, has spent the last two years assembling a museum-quality collection of contemporary Southern photography — from the late 1950s through the present. The Fund’s intent is not simply to create a repository of photographs that can travel from gallery to gallery being fawned over by the wealthy and/or the erudite.

The real aim, according to the Fund’s mission statement, “is to make these works broadly accessible” so that they will spawn conversations among Southerners — so that we can understand our culture, our history and each other a little better. If the Do Good Fund continues on its current trajectory, it could wind up being the most important thing to happen to Southern photography since Walker Evans came to Alabama in 1936.

Top two photographs by Keith Carter: “Garlic,” from 1991, and “Chicken Feathers,” from 1975. Bottom three photographs: “The Taxidermist's Son” by Deborah Luster, then two 2006 photographs by Dave Anderson, “Breeze” and “Jug Riding.”

To hear Rothschild tell it, Walker Evans got this whole thing started.

“For me, the starting place of my interest in photography is this story that starts back, I think, even in high school,” he says. “We had ‘Let Us Now Praise Famous Men’ as a textbook for either a Southern Lit course or another course about the South.”

For the uninitiated, photographer Walker Evans and writer James Agee traveled to Depression-era Alabama on an assignment from Fortune magazine — although Fortune chose not to run their story. Instead, the photographs and interviews they did became a book, “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men,” published in 1941, a starker, more pointed look at rural poverty in the South than the wider world had ever seen.

“Walker Evans’ photographs in that book just really struck me,” Rothschild says. “What I realized in high school and in college is that in the typical history textbooks, you would have the Civil War in eight pages, the Depression in four pages, the Civil Rights movement in six pages. You would have all this information just crammed in there, and they in large part tried to teach about statistics. They would tell you that at Gettysburg, there were 50,000 casualties. I don't know what that looks like. Then you see a Matthew Brady image of a dead, bloody soldier in the trench, and all of a sudden it makes a war that's 150 years old very real and very present.

“In the Depression chapters, they’re talking about things like a 50 percent unemployment rate. I don't know how to interpret that. Then you see Walker Evans' pictures of how poor and desperate the white tenant farmers were, which makes you think, well, imagine what the black tenant farmers must've had. I just have always found that photography told me a lot more about American history and in particular Southern history — where we come from and where we are today — than lots of volumes of text did,” he concludes.

In Rothschild’s case, it appears the old cliche is absolutely true: To him, a picture is worth a thousand words. Maybe even millions.

“The Lynn Fork Women” and “The Lynn Fork Men” by Shelby Lee Adams.

The goal of the Do Good Fund’s collection is to use its photographs to provoke conversations about the South’s history, its present state and where it’s going. In December, almost the entire collection finished a residency at the Lamar Dodd Art Center at LaGrange College, on Central Georgia’s western edge. I visited the Dodd Center one quiet Saturday morning with Rothschild as my guide. Seeing the collection mounted in a beautiful museum space, it’s very hard to quibble with Rothschild’s curation over the first two years of the collection’s life. Although the Do Good Fund’s acquisition budgets remains too small to allow the inclusion of the work of a few iconic Southern photographers, such as William Eggleston and Sally Mann, what Rothschild has amassed in only two years is remarkable in its scope.

The collection ranges from images that bring to life the struggle of African-Americans in the Jim Crow-era South to contemporary images of modern Southern cities and rural communities. Their creators range from globally celebrated names such as Gordon Parks and William Christenberry to current photographers such as Tamara Reynolds and Maude Schuyler Clay, whose photographs have appeared in The Bitter Southerner, to younger photographers of significant talent but not much fame.

“I love the fact that he’s putting lesser known photographers on equal footing with more widely known photographers,” says Amy Miller, the executive director of Atlanta Celebrates Photography, a 17-year-old nonprofit that organizes what it calls “the largest annual community-oriented photo festival” in the United States.

The earliest photos in the collection do come from one of the South’s most celebrated photographers, and they date back to 1956. Recent acquisitions, they are a pair of images that Parks, the late African-American photographer, captured for a Life magazine series on segregation. One image features the Thorntons, a black couple who lived in Choctaw County, Alabama, on the Mississippi border near Meridian. In the photograph, the couple sits dressed in their Sunday finest on their sofa, beneath another photograph of themselves, from 48 years earlier, on their wall.

“I've got the old Life Magazine out in the car,” Rothschild tells me. “Their daughter was a schoolteacher. She was quoted as saying something about how this picture presents the upstanding black citizens of Choctaw County and that the other images present the dire circumstances that these folks live in. The daughter was also quoted in the article saying something like, ‘The only way it's going to get better is through integration.’ After the issue of Life was published, (the white citizens of Choctaw County) basically ran the family out of town. Life magazine ended up giving them something like $25,000 to help them relocate to Mobile and start their life over because the article had caused them to get run out of town.”

Looking at the picture and hearing the story seems to prove Rothschild’s premise about the potential of a single image to teach us our history.

Two photographs by the late Gordon Parks, both from 1956, “Mr. and Mrs. Thornton” and “Department Store, Mobile, Alabama.”

The history lesson gets even more dramatic a couple of galleries over with the late Charles Moore’s 1963 image, “Alabama Fire Dept. Aims High-Pressure Water Hoses at Civil Rights Demonstrators, Birmingham Protests.” In the photograph three young black protestors — two men and a woman — cling desperately to a doorframe in their effort not to be knocked over by about 200 pounds per square inch of water pressure.

“Charles Moore is … more so than many of the civil rights photographers, he put you right there in it,” Rothschild says. “You compare that to the Gordon Parks images on the other side. They’re both doing the same thing, trying to document and express their opinions about what was going on in the South in the 1950s and ’60s.”

Rothschild points to the second of Do Good’s recently acquired Parks photos.

“Parks does it in a much more subtle way,” he says. “He gets this lady and her daughter to dress up in their Sunday best and go stand outside of a color entrance of the movie theater, and it's a very artistic portrait. That was his tool to fight segregation. But this Charles Moore is a very dramatic image, and this is a hard image for the curators to place, because it's the action shot. This is street photography. You know his life's at risk; he's right there with them.”

It might be more accurate to describe Moore’s image as battlefield photography. And the history lesson it teaches is inescapable: The battlefield was the streets of Birmingham, and the battle happened a mere 50 years ago — not within all of our readers’ lifetimes, but certainly within this writer’s.

Moore’s photograph thrusts the viewer directly into the pain of that dark day almost 52 years ago. It rattled me so hard I almost had to turn away from it.

The late Charles Moore’s “Alabama Fire Department Aims High-Pressure Water Hoses at Civil Rights Demonstrators, Birmingham Protests, May 1963.”

The Do Good Fund’s beginnings date back to Rothschild’s role as a trustee of a Columbus-based foundation. Every year, that foundation’s trustees were allowed to recommend how a certain portion of the foundation’s endowment should be directed. The foundation supports a variety of charities, but Rothschild’s idea was to consolidate some of its funding to the arts.

“What I was doing was supporting a variety of endeavors, lots of regional museums: the Columbus (Ga.) Museum, the Georgia Museum in Athens, the High Museum in Atlanta,” Rothschild says. “But I realized that if you give any museum $700, that's nice, but it is going to continue to do just what it was doing. So after thinking about it some more, a group of us formed a new public charity called the Do Good Fund in 2012, and instead of dividing this grant up among 20 different organizations, the majority of it's going to the Do Good Fund. That's been the initial source of capital to start this project.” And now, after that seed funding helped Do Good off the ground, it is beginning to receive additional funding from other sources.

Museum supporters who work like dogs to keep their institutions afloat might not like hearing such declarations, but Rothschild believes the Do Good Fund’s approach is realistic in the face of reality: The rise of electronic media is pushing museum and gallery attendance down dramatically.

The National Endowment for the Arts’ most recent survey of public participation in the arts showed that 71 percent of Americans said they consume art through electronic media, while only 21 percent said they attend museums or art galleries.

These figures butt headlong into the more subjective reality that to see these photographs carefully printed on large sheets, framed and displayed on the walls of a physical space is an experience that electronic media simply cannot match. To feel their full weight, you have to go see them in person. There is too little real estate on a computer screen to do them justice.

That clash — dropping museum attendance vs. the obvious superiority of the museum experience — drives the Do Good Fund’s approach to displaying its collection. Yes, you can see the photographs in proper museums, such as the Dodd Art Center, where I saw them. But you can also see them in remote places like Perry County, Ala., just northwest of Selma, where Do Good will mount a show this May. Rothschild wants the collection to find destinations in traditional museums as well as these nontraditional venues. To him, both have equal value.

Two photographs by Brandon Thibodeaux: “Harry Hope, Mound Bayou, Mississippi” and “Birds in Field, Mound Bayou, Mississippi.”

From a practical standpoint, shows in places like Marion, Ala., make absolute sense: If fewer people are going to museums, then perhaps the museum should be taken to the people. Atlanta Celebrates Photography’s Miller endorses Do Good’s approach.

“It’s tremendously valuable,” she says. “Our organization does a big public art project every year for that very reason. It’s a way to expose people to art in unexpected places. And those unexpected encounters are often the most powerful. Alan seems to understand that really well. He seems to have it as a priority, to bring this collection to places that might not have traditional arts venues.”

But on a historical and cultural level, Do Good’s intention is to allow the people who live in Southern communities where history was made to see how our great photographers captured that history.

Consider the lessons these photographs might teach in a place like Perry County, which carries a very specific historical burden. On Feb. 26, 1965, state troopers there beat, shot and killed Jimmie Lee Jackson, a 26-year-old African-American deacon of the St. James Baptist Church in Marion, as he tried to protect his grandfather and mother when troopers attacked civil rights marchers. Jackson’s death was the spark beneath the Selma-to-Montgomery marches, which began about a week later.

Putting up a show in Perry County “just makes sense to me,” Rothschild says. “A lot of these images are from the rural South. The Black Belt of Alabama and the Mississippi Delta are places that are very popular in Southern photography because they're still isolated from a lot of the modern influences. The folks that are the subjects of these photographs rarely have an opportunity to see these photographs that depict them or depict their way of life, but we hope to take the photographs to those people.”

Three photographs, all untitled, by Susan Lipper.

The brilliance of the Do Good collection, even at this early stage of its development, is the fact that “those people” could be almost anyone in the South, regardless of race, class or specific location. Looking at the full range of the photographs, you realize they look at the South from an extraordinarily wide — and still widening — variety of perspectives.

There are simple slices of life such as Susan Worsham’s 2011 image, “Young Boy Cleaning Church.” Landscapes like Joshua Dudley Greer’s “Gray, Tennessee” ask us questions about the encroachment of suburban life on previously rural environs. Dave Anderson’s “Maxine at Dusk” and “Tool Belt,” from 2008, take us directly into the lives of New Orleanians rebuilding their city in the years following Hurricane Katrina.

And then there are images such as Dennis Darling’s “Family at Klan Rally, South Carolina,” to remind us who we are at our filthiest.

Taking these images to nontraditional venues seems to give them even greater impact. In September, the Do Good Fund mounted a show in a 140-year-old whiskey bonding barn in Zebulon, Ga., population less than 1,200. I ask Rothschild how the people of that rural community responded to the photographs.

“Many of the sentences started out with ‘I remember…,’” he says.

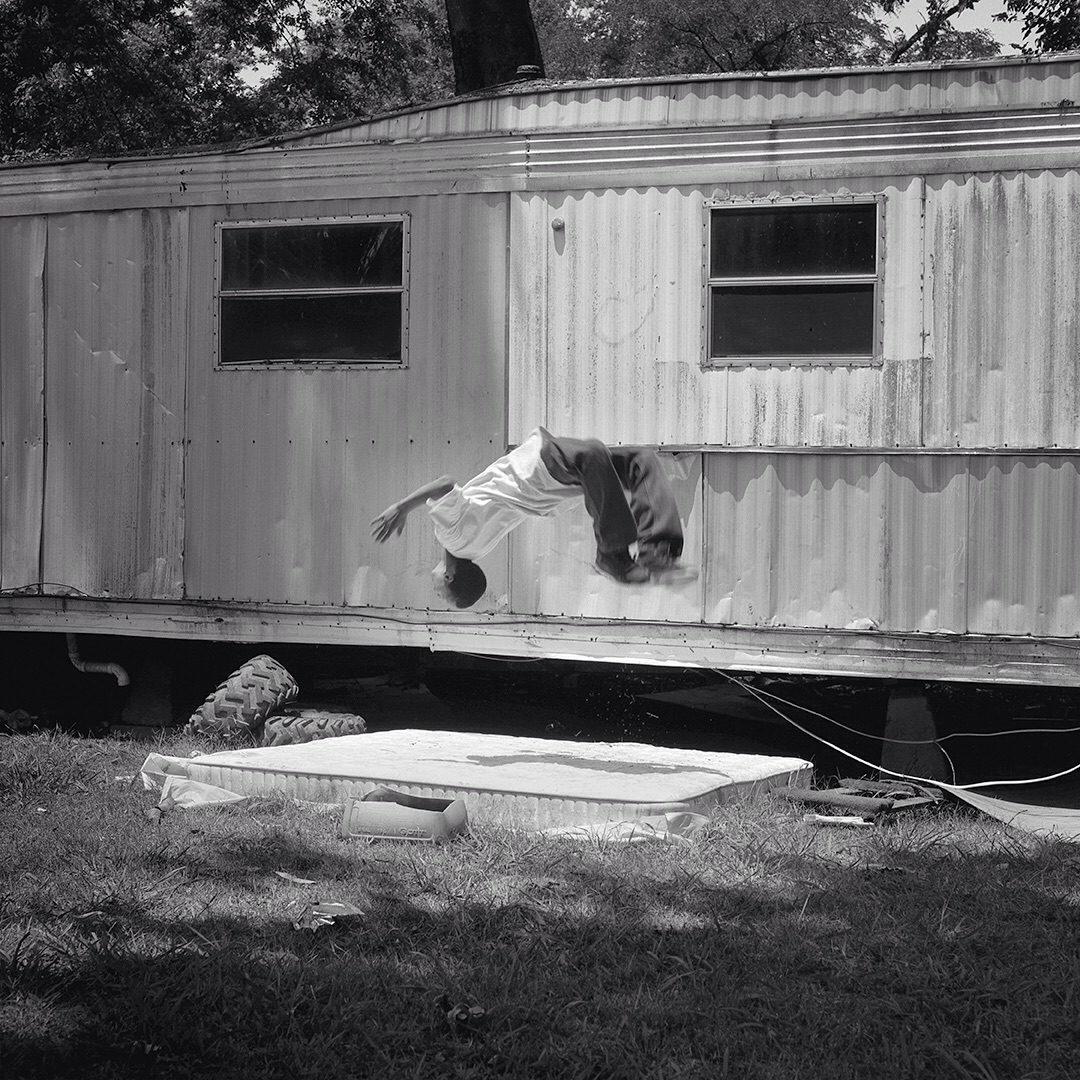

Top three photographs: “Backflip, Duncan, Mississippi,” by Brandon Thibodeaux, “Harry's Hands, Winter, 1984,” by Debbie Fleming Caffery, and “Woman, Rosedale, Mississippi,” also by Thibodeaux. Bottom two photographs are both by Dennis Darling: “Ku Klux Klan Member and Wife, East Texas, 1975” and “Family at Klan Rally, South Carolina.

In a way, that sums up the magic of Do Good’s approach to collecting and displaying photography. In a big-city museum, this collection might provoke discussions about artistic merit — composition, color saturation, all the technical elements of great photography. In an old barn in Zebulon, something else happens: The photographs call up memories and provoke discussions about Southerners’ shared histories.

Do Good’s work to create deliberate community involvement in the exhibitions drive those discussions even further. While the collection hung in the Dodd Center, teachers at LaGrange College and nearby Auburn University and Columbus State University incorporated the exhibition into their classes. Earlier last year, in March, CSU art students curated a show from the Do Good collection in a vacant storefront in downtown Columbus, and four of the photographers with works in the collection came to town to teach photography classes or take high school and college art students on photo-shooting expeditions, followed by critiques of their work.

Top two photographs by Eliot Dudik: “Alligator Alley, Oregon Road, Road Ends in Water” and “Condemned, Ashepoo River.” Middle three photographs: “Untitled,” by Rylan Steele, then “Ponce de Leon Springs, Florida” and “Gray, Tennessee” by Joshua Dudley Greer. The bottom two photographs are both by Caitlin Peterson: “Tallulah Gorge” from 2013 and “Stone Mountain” from 2012.

Rothschild refers me back to photographer Mike Smith’s quiet landscapes from Tennessee and North Carolina.

“He goes and documents the most ordinary things he can, like just a little scene of winter grasses in eastern Tennessee,” Rothschild says. “Anybody driving through any rural part of the South in the wintertime is familiar with all these brown and gray grasses flying by your car, and you don't pay any attention to them. But Mike’s got the foresight to stop and construct the photograph and document an unbelievably beautiful scene of something we just totally take for granted.”

I tell him I think that might be the essence of all great photography — the ability of the artist to recognize that he or she is in a particular moment, in a particular place, that is worthy of being committed to memory.

“I still remember the impact that Walker Evans' photographs from Hale County, Ala., had on me,” Rothschild says. “I'm interested in cultural arts, and I'm interested in history, and I think these narrative photographs combine those interests. Hopefully, they're perceived by people as beautiful works of art, but they're also works of art that tell stories about the South.

“On one level,” he continues, “it's fine for me if people just want this to be a collection of contemporary photography from an artistic standpoint, an answer to the question, ‘What are people taking images of in the South today?’ We've got lots of emerging artists in the collection, and their work speaks to that. But I think that's selling the collection short. I think there's much more to this than looking at it as just a work of art and looking at the colors and shapes and some of the technical aspects of the photograph.

“The real story for me is what the photograph is about — whether it's the vanishing country store or the expansion of suburbia and how that impacts the South, or what they tell us about what's likely to happen in our communities going forward,” he says.

“Maxine at Dusk” and “Tool Belt,” both by Dave Anderson, from New Orleans in 2008.

Sometimes, Rothschild says, art-world people look at the collection and ask him whether the idea of “Southern photography” even matters anymore — and whether, in an age when young people are no longer shaped exclusively by the communities that surround them, “the South” even remains a distinct region.

“I think you and I would disagree with that,” Rothschild says, and he’s absolutely right. Otherwise, this very publication would not exist. But we do have to admit that, as Rothschild says, “it's not a clear line.”

Two New Orleans images by Sophie Lvoff: "Simon Bolivar Avenue (Hot Spot)" and "St. Bernard Avenue (Sardine)."

When these pictures depict poverty or oppression or rural practices or even our sense of play, they show us conditions that are certainly universal. All over the world, people suffer in poor living conditions. All over the world, people have their own ways of living and having fun.

But taken together, these images are distinctly and inescapably Southern — from Keith Carter’s otherworldly shot of an African-American farm woman shaking the dirt from freshly pulled garlic bulbs to Tamara Reynolds’ tender images of working-class people in Nashville and across southern Appalachia to the legendary William Christenberry’s image of China Grove Church sitting in the bend of a Hale County dirt road. We see ourselves in them. They make us remember. And perhaps most importantly, they make us talk to each other about who we are and why we think the place we come from matters.

‘’We’re not building this collection to answer the question, ‘Is there still a distinct South?’” Rothschild says. “We're just building the collection so that people can have those conversations.”

In that sense, these pictures are no different than food on the common Southern table. They have the power to pull us together, in conversation, to learn more about what we have in common and to defeat the old forces and traditions that pull us apart.

"Belly" by Magdalena Sole.

Header photo: “1996” by Mark Steinmetz