Earl King’s lyrical blues and electric stage presence set him apart. But he’s never been properly honored as a Louisiana writer who penned songs for Dr. John, the Neville Brothers, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and Jimi Hendrix. Geoffrey Himes writes this remembrance of King who died in 2010 and would have turned 87 on Feb. 7. New Orleans doesn’t have a poet laureate, may we suggest this posthumous honor for the King?

By Geoffrey Himes

Photos by Michael P. Smith

New Orleans, December 1998

The long, narrow shotgun houses had colored lights wrapped around the porch posts, but the weather was a balmy 60 degrees. Down on Tchoupitoulas Street, near the Mississippi River levee, sat one of the city’s classic seafood joints, Frankie and Johnny’s, named after the old blues song. The rambling, ramshackle building may have had a stained drop-ceiling and ugly paneling, but the food heaped on the checkered tablecloth — boiled shrimp, fried oysters, crawfish pie, gumbo, and muffaletta sandwiches — made the mouth water and the belly purr.

We were having a late dinner with Hammond and Nauman Scott, owners of the hometown Black Top Records, and the label's flagship artist, Earl King. The conversation drifted from record distribution to soap operas to big-band jazz to Voodoo. As on every aspect of local culture, King possessed encyclopedic information and a rollicking good story about this last topic. He told of watching old friends go into New Orleans’ storefront Voodoo shops to stock up on the necessary candles, oils, and soaps for the coming week. He told of his old friend Charles, a self-appointed Voodoo priest who could change the color of his eyes, grow a beard overnight, and talk the police out of an arrest like Obi-Wan Kenobi.

So did King himself subscribe to Voodoo? “Naw,” he declared with a dismissive wave of the hand, “I don’t believe in none of that mess. People say they’re going to put a spell on you, but I don’t pay them no mind. I knew Charles was a magician before he started talking all that Voodoo stuff. I like to know about it, because it intrigues me, but I don’t take it seriously. These other people out here, they really believe it.”

King wasn’t nearly as well known as many of the men he collaborated with — Fats Domino, Dr. John, Professor Longhair, the Neville Brothers, Lee Dorsey, Allen Toussaint, Huey “Piano” Smith, and Ray Charles — but he crafted some of the best songs to ever come out of Louisiana. And to the extent that songs are likely to outlive singers, he may yet become the most enduring figure of the golden era of New Orleans R&B.

As with Voodoo, King knew the ins and outs of every musical style to ever pass through New Orleans in his lifetime, but he remained wary of the scene’s more dubious myths. The most seductive and dangerous of those myths is the belief that the city’s songs should be as spontaneous and uncalculated as the carnival parades they spring from. If you came up with a clever title, a catchy tune, and a jiggly beat on the spur of the moment, many of his peers believed, there was no need to go back and fine-tune the verse lyrics or the chord changes.

“I hear records all the time on the radio that with a little time and a few little changes here and there could have been monstrous songs,” King said. “It sounds like someone said, ‘I’m just going to do this right here,’ like they couldn’t be bothered with it no more. Sometimes just a little twisting and a little tender care can turn something OK into something great.

“I tell all new writers, ‘You have to be your own critic.’ Don’t think just because you wrote something the first time, that's it. No, no, things don’t work that way. You’ve got to be able to put that down and say, ‘These are my first thoughts.’ It’s like looking at a woman you just saw once and everything looks great and two days later you jump up and want to get married. You’ve got to think about that a little bit. You need that second thought.”

This approach to songwriting inspired artists as diverse as Jimi Hendrix, Robert Palmer, Dr. John, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Fats Domino, Boz Scaggs, Lee Dorsey, Dusty Springfield, Levon Helm, the Dixie Cups, Professor Longhair, and the Neville Brothers to record King’s songs (see sidebar and Spotify playlist at the end of this story). And yet it was King’s own recordings that make the best case for his lasting importance. A vivid vocalist and gonzo guitarist, King filled his singles and albums with as much snap, crackle, and pop as any that ever came out of New Orleans. But an unbroken string of bad luck with record companies kept him from ever having a national hit.

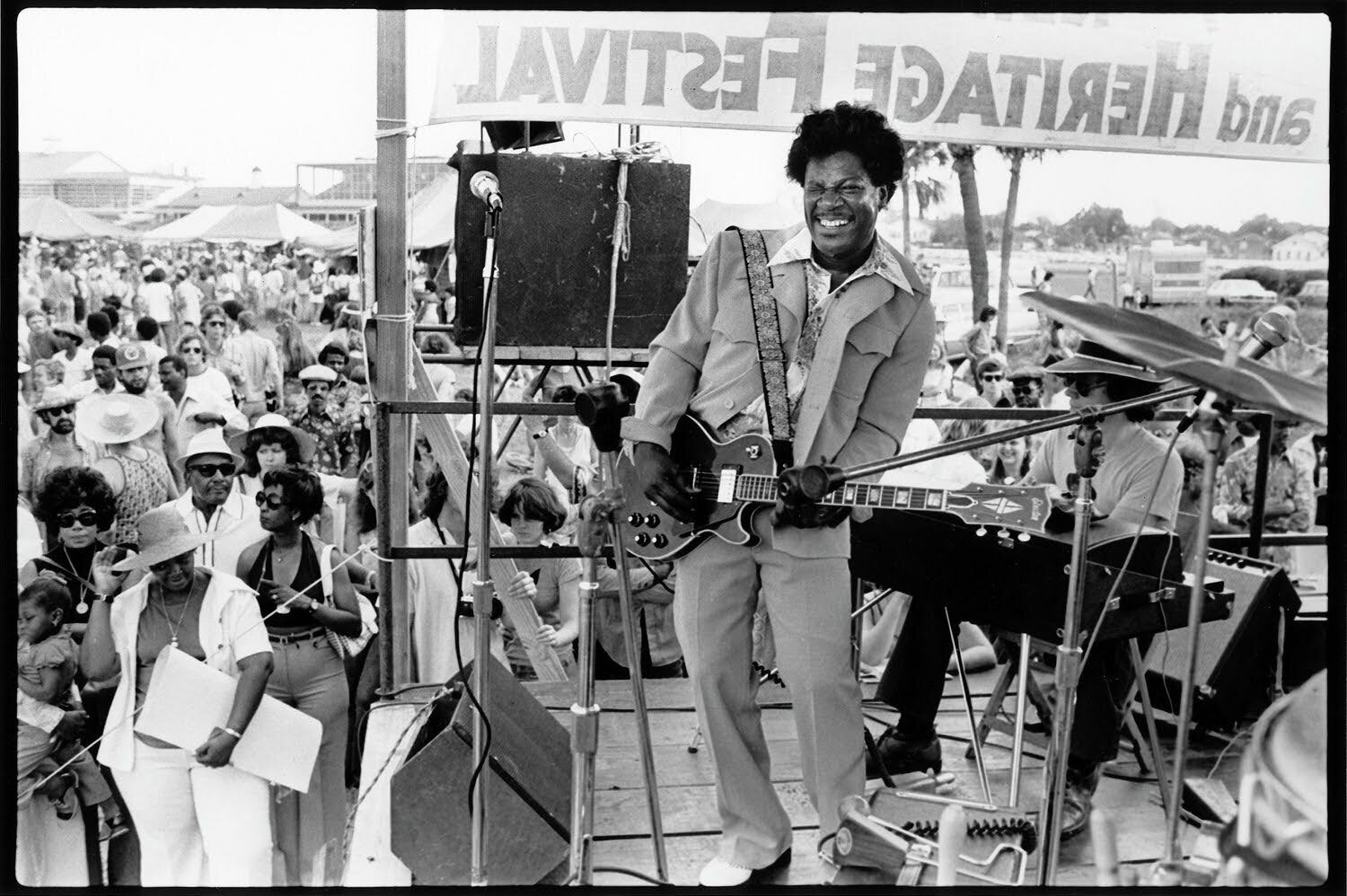

Although Jimi Hendrix, Robert Palmer, Dr. John, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Fats Domino, Boz Scaggs, Lee Dorsey, Dusty Springfield, Levon Helm, the Dixie Cups, Professor Longhair, and the Neville Brothers all recorded Earl King’s songs, he never had a national hit. Pictured above is Earl King with Stevie Ray Vaughan at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival in 1986. Photograph by Michael P. Smith ©The Historic New Orleans Collection.

When we look back at the 1950-1965 golden era of New Orleans R&B, the sales figures don’t matter as much as what's in the grooves. King’s discs were among the rare ones where the words were as important as the music, where blues guitar was balanced with second-line piano, and where the B-sides were as strong as the A-sides. Due to that work ethic, King and Toussaint were able to write important new music for themselves and others into the 1990s while their contemporaries had been relegated to the oldies circuit.

As he wolfed down oysters and iced tea at Frankie and Johnny’s, the 64-year-old King was dressed casually in black running shoes, dark green slacks, and a shirt that ran riot with green, blue, and red splotches. A thin hint of a mustache crawled across his upper lip, and his thinning conk refused to stay in its appointed comb paths. As he expounded on his theory of songwriting, he talked in a chuckling, rumbling, Louisiana baritone. An embryonic smile kept tugging at the corner of his mouth, but the listener was never sure who the joke was on.

“Performing and writing are two totally different things,” he insisted. “When you’re performing, everything happens right then, but when you’re songwriting, you’ve got the privilege to stop and think about it. Most songs, I’ve got to rewrite them. I go back to look at the first version of a song, and I say, ‘Man, I’m glad I didn’t use that.’ It just wasn’t gelling; it just wasn’t saying what I wanted to say. Songwriting keeps me on edge. I could never get bored doing it. I could get tired, but never bored.”

Once King’s songs were written, though, they became the basis for one of the most spontaneous stage acts around. I especially remember one night at the House of Blues in the French Quarter on the last night of the 1994 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. King took the stage in a sparkling white, double-breasted suit and a bright red Stratocaster guitar. Backed by a horn-heavy band from Texas, King jumped into his blues shuffle, “Love Rent.”

The lyrics about an older man paying his “love rent” to a younger woman had the same satiric bite as the recorded version, but the guitar solo entered a whole different dimension. King’s pointed, prickly notes seemed to jab at the chord changes; soon they deserted the changes altogether and jumped into unknown territory that had the all-star band scrambling to follow their leader's unplanned tangent. Before long, King was lost in his own zone as he closed his eyes, planted his guitar against his hip, and picked out fast and furious runs as he hopped about the stage on one leg. His hair, so wavy and shapely at first, was now sticking out in odd tufts in all directions.

“He reminds you of falling off a cliff,” said Hammond Scott, who was the House of Blues emcee that night. “He starts thinking about where he wants to go and doesn’t think about any of the rules. He gets into this trance sort of thing, and, in looking for a certain area on the guitar, he transcends keys a lot. I asked a drummer once what it was like backing up Earl King, and he said, ‘It’s a lot of fun, but it's like playing with your hair on fire. You never know what’s coming next.’”

Earl Silas Johnson IV was born on Feb. 7, 1934. He wouldn’t become Earl King until 1954. He grew up in New Orleans’ Irish Channel neighborhood, an unusually integrated area. His father died when he was 18 months old, and it was only later that King learned his dad had been a blues pianist before becoming a preacher. King was raised by his mother, Ernestine Hampton Johnson, and his stepfather, Nathaniel Gaines, who made sure the youngster first learned to sing in the Antioch Baptist Church.

In 1949, though, a 21-year-old Fats Domino released a single called “The Fat Man.” Produced and co-written by trumpeter/big-band leader Dave Bartholomew, the song married the jump-blues of Louis Jordan to the distinctive second-line syncopation of New Orleans. With Domino pounding out a piano-boogie riff and crooning the lyrics in his creamy baritone, the song was irresistible. It became a huge R&B hit nationwide and proved to ambitious locals such as the 15-year-old King that a young singer could take the hometown sound and become a star.

King couldn’t wait until he was old enough to get into the nightclubs. By dressing up in a suit with a fedora pulled down over his eyes, he could sneak into joints and soak up the music. He also began hanging out at the offices of local talent scouts.

Thus it was that he visited one scout in a shop with the sign in the window, “House of Hope — Dr. Mighty the Voodoo Man.” In the back room, beyond the incense and candles, was an impromptu rehearsal room, where a 15-year-old pianist was banging out syncopated patterns. It was Huey Smith, who just a few years later would have national hits with “Don’t You Just Know It” and “Rockin’ Pneumonia and the Boogie Woogie Flu.”

“Huey asked me if I’d like to sing with this little group he had,” King recalled. “I said, ‘I don’t know; I don’t know any songs.’ Huey told me, ‘That's no problem; if you can sing in church, you can learn some songs.’ So we learned two or three songs to start with and started playing at the Moonlight Inn in Algiers across the river.

“The guy who owned the Moonlight said, ‘The people here seem to like you, but I can’t afford to hire no more pieces, and we need a guy who can both sing and play the guitar. This is Guitar Slim territory over here.’ I thought that left me out, but Huey said, ‘We’ll fix that up.’ Huey had a little guitar, because he had played with Slim, and he let me fool around with it for a month or so. I got interested in that guitar and started working at it.”

It was through Smith that King met his greatest influence, Eddie “Guitar Slim” Jones. A blues guitarist and singer who borrowed much of his style from Aaron Thibeaux “T-Bone” Walker and Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Guitar Slim was the most flamboyant showman in a city that also contained Little Richard.

“Imagine you never saw James Brown but you had heard him on record,” explained King. “You might say, ‘This is alright,’ but to understand where he was coming from, why he was meaningful, you had to see James. The same was true with Slim. People used to call him the Reverend Limber Legs Slim, because his legs looked like they didn’t have no bones in them. They had rafters in the ceilings of them old clubs, and Slim would be hanging from the rafters upside down and playing his guitar.

“You can go into a store now and buy any color of shoes you want to buy. But you couldn’t do that back then, so Slim would get him a bottle of paint and spray paint them shoes and set them out in the sun and let them dry. Then he would dye his hair the same color. Then he would wear a suit to match the color of his shoes and his hair.

“He was the one who started using that long, 300-foot guitar cord so he could roam around the club. Slim is the only one who could walk into the women's dressing room playing his guitar and the women would laugh about it. Anyone else would be dead. I’ve seen Slim have men standing at the bandstand crying. Even the regulars who see him every day would think nothing of driving out to Beaumont, Texas, to see Guitar Slim. He was a character.”

Dew Drop Inn building, LaSalle Street, New Orleans.

Smith, King, Guitar Slim, and the other young musicians in town hung out in the clubs clustered around Dryades, Rampart, and LaSalle Streets in the bustling center of New Orleans’ Black community. King won the Wednesday night amateur contest at the Dew Drop Inn so often that he was disqualified and had to move over to the other main club, the Tiajuana.

“There was no other club like the Dew Drop,” King maintained. “When you walked into the Dew Drop, you didn’t just hear musicians and singers. You saw comedians, actors, dancers, the whole gamut. All the big names came through there — Nat King Cole, Duke Ellington, Dinah Washington, Count Basie — and they would see their pictures in a mural that Frank Painia, the owner, had put up there. Frank’s brother, Paul, had a cafeteria in the back. There was also a barber shop and a hotel in the building.

“We had showtimes at midnight and maybe another at 3 in the morning. And after the last show is over, here come all the musicians, waiters, and bartenders from all the other clubs to hang out. The jams could go till sunup. I got a chance to play with just about everybody in New Orleans, people I was elated to be associated with.”

Guitar Slim had his breakthrough hit in 1954 with “The Things That I Used To Do,” a tune that has since become a blues standard. With the first flush of money, Slim bought a new car and promptly drove it into a parked bulldozer, putting the car in the garage and himself in the hospital.

This created a real problem because his agent had already booked him into clubs throughout the South. Fortunately, 78s and 45s didn’t have pictures on the covers in those days, so fans didn’t really know what Slim looked like. So the plan was hatched — King would hit the road as Guitar Slim.

“He reminds you of falling off a cliff,” said Hammond Scott.“He starts thinking about where he wants to go and doesn’t think about any of the rules. He gets into this trance sort of thing, and, in looking for a certain area on the guitar, he transcends keys a lot. I asked a drummer once what it was like backing up Earl King, and he said, ‘It’s a lot of fun, but it's like playing with your hair on fire. You never know what’s coming next.’” Photograph by Michael P. Smith ©The Historic New Orleans Collection.

“The first booking was Atlanta's Magnolia Ballroom,” King remembered, “and I had never played for an audience that big in my life. They had banners over the street saying Guitar Slim. It scared me half to death. Mr. Beaman, the owner, asked, ‘Which one of you guys is Guitar Slim?’ Oscar Moore, the drummer, pointed at me. Mr. Beaman looked at me and said, `You don’t look like no guitar player to me.’

“That was a bad place, that Magnolia Ballroom. As we were setting up the instruments, this guy with a switchblade in his hand said, ‘When you get on stage, I want to hear ‘The Things That I Used To Do” 13 times.’ After we walked away, Oscar said, ‘Earl, what are we going to do?’ I told him, ‘I guess we’re going to play “The Things That I Used To Do” 13 times.’ Then this little dancer from New Orleans came into the dressing room and shouted out, ‘Hi ya, Earl,’ and I told her, ‘Hush up or you’re going to get us all killed.’

“Meanwhile, Ray Charles is the opening act, and he got the crowd all worked up. So I’m really scared when it’s our turn to go on. But once I got on stage, my adrenaline took over. As soon as I sang one line of ‘The Things That I Used To Do,’ all hell broke loose. Women were screaming and money started flying on the bandstand. The guys put down their instruments and helped me collect the money on stage. Man, it was awesome.

“About a year or two later, I went back there, because I had my own hit with ‘Those Lonely, Lonely Nights.’ I walked in and said, ‘Hey, Mr. Beaman, do you remember me?’ He looked at me and said, ‘Your face looks familiar, boy.’ I said, ‘Guitar Slim.’ He said, ‘Oh, Lord. Who are you now?’ ‘Earl King.’ ‘Really?’ ‘Really.’”

When he wasn’t impersonating Guitar Slim, King was writing his first songs in the style of Big Joe Turner. His first single, “Have You Gone Crazy” was credited to Earl Johnson and released by Savoy in 1953, but it went nowhere.

King had better luck the following year when he cut “A Mother's Love” for Specialty Records and scored a Gulf Coast hit. The song sounded so much like King’s mentor that many jukeboxes attributed the song to Guitar Slim. The label on the record itself was supposed to read “King Earl,” a DJ's nickname for the young singer, but the pressing plant got it wrong and printed it as “Earl King.” That’s what he's been called ever since.

In 1955, Johnny Vincent, the Specialty A&R man in New Orleans, left the company and started his own label, Ace Records, in Jackson, Mississippi. Vincent invited King up to Jackson to record, and that first night, the singer cut “Those Lonely, Lonely Nights.” Smith played the hypnotic piano triplets and King sang the insinuating melody with the pleading ache of someone left all alone by a former lover.

The released version is marred by out-of-tune guitar and piano, but Vincent favored it over the cleaner takes because he thought the vocal was so emotionally grabbing. He was right, for the song became a big hit in the South and might have broken out nationally if Vincent hadn’t procrastinated and given Johnny “Guitar” Watson a chance to release a cover version. It wouldn’t be the last time that record-company bungling would cheat King out of a national hit.

“When Slim heard me do ‘Lonely, Lonely Nights,’” King recalled, “he said, ‘Now, Earl, you see that bag you’re in; stay right there. Leave my stuff alone.’ ‘Lonely, Lonely Nights’ was a whole world of different from what I’d done before. Really and truly, I wrote that song with country in my mind. That piano part was supposed to be a mandolin. I hummed that part to Huey, and he wound up playing it on piano, because we couldn’t find a mandolin player. I listened to a lot of country then, and I still do. Those country guys can come up with one hell of a lyric.”

When King married the confessional lyrics and sweet melodies of country to the blues guitar of Guitar Slim, the second-line piano of Huey Smith and the irreverent satire of Percy Mayfield, King had a style like no one else. He began writing and recording one fascinating song after another. “Well’o Well’o Well’o Baby” and “Everybody Got To Cry” (credited to “Handsome Earl”) were modest hits, but he was unable to follow Smith and Domino onto the national charts.

“In 1960, I went out on tour with Sam Cooke,” King said. “Every night I opened the show with this new song called ‘Come On.’ People started clapping and screaming and carrying on, though I had never even recorded it. So when I got back to New Orleans, Dave Bartholomew said, ‘That song you do every night, whose song is that?’ I said, ‘Mine.’ He said, ‘We’re going to cut that song.’ That’s how I got with Imperial Records.”

“Come On (Let the Good Times Roll)” marks the first full flowering of King’s gifts as a lyricist and guitarist. Lines such as “You got me flippin’ like a flag on a pole” are delightful tongue-twisters and the guitar solo inspired Hendrix and Vaughan to do their own versions later. One thing that separated “Come On” from the other New Orleans records of the time was the fat, throbbing bass track.

“A lot of New Orleans records didn’t have enough bass on them,” King asserted. “You’ve got to have something that really has that pulsation, and the electric bass is the thing. If you subtract it, you’ll see the difference. The upright has a truer sound to it, but it's not going to penetrate that nervous system like a Fender bass. When I’m making a record, I think bass before I think anything else.”

Bass was just as prominent on King’s 1962 single, “Always a First Time,” a top-20 R&B hit. When he released one of his greatest songs, “Trick Bag,” that same year, he seemed poised for national success at last. But once again the fates intervened. Just as “Trick Bag” was being released, owner Lew Chudd decided to shut down Imperial Records because the label's main money-maker, Fats Domino, had moved over to ABC Records.

“The upright has a truer sound to it, but it’s not going to penetrate that nervous system like a Fender bass. When I’m making a record, I think bass before I think anything else.”

Before long, though, another opportunity came knocking. In 1963, local promoter Joe Jones claimed he had landed a contract for a group of New Orleans artists with Motown Records. But when King arrived in Detroit with Jones, he found out there was no contract, just an audition. Nonetheless, the Motown execs were so impressed with King’s songwriting and Smokey Johnson's drumming that they started recording tracks on the Louisiana visitors around the clock.

“The whole thing at Motown was different,” King said. “They were open 24 hours a day, cutting stuff. One time I was recording a song and a producer came in and said, ‘Hold tight, I’ll get you some background singers.’ He got someone from the Contours and someone else from Martha and the Vandellas at 5 in the morning and we did it right there.

“I could see how those songwriters could get intrigued with the setup at Motown, because everything you need is provided for you. Background voices, whatever musicians you need, you have all that at your disposal. So that makes it easy. I got a lot out of being up there at Motown. I was inspired to do a whole lot of writing when I came back.”

King wrote and produced about two dozen songs for Motown, not only on himself but also on such artists as Joe Jones, Patti Little, and the Contours. But with Jones demanding a lot of money for his non-existent rights to the New Orleans artists and Motown offering less money than they could make at home, King and the rest packed their bags and returned South. Except for three songs on the 1996 compilation, “Blue Evolution,” none of King’s work for Motown has ever been released.

Still, he was undaunted. He returned to New Orleans fired up with creative energy, determined to write songs for all his favorite artists in town. At the top of the list was Professor Longhair, the eccentric pianist with the rumba beat, and King had just the right song for him, “Big Chief.”

“My cousin Roscoe nicknamed my mama ‘Big Chief,’” King explained. “He used to say, ‘Earl, if you haven’t mowed the lawn, if you ain’t washed the dishes, when Big Chief comes home, she's going to go on the warpath.’ That gave me the idea for the song, and I decided to do it with Fess.

“In the beginning I was playing the left hand and the chords on the piano, and Fess was playing that melodic thing. When he couldn’t get the words together, Joe Assunto, the producer, said, ‘Earl, get off that piano, get in that booth and sing the song. We’ll try to cut it with Fess later.’ But they never did. So that's me singing and whistling on the record. They were supposed to put my name on the record but they never did that either.”

He continued to write such memorable songs as “Teasin’ You” for Willie Tee, “Part of Me” for Johnny Adams, and “Let's Make a Better World” for Dr. John. King recorded an album with the Meters and producer Toussaint in 1972 for Atlantic Records. But the deal fell through and the music went unreleased until Charly Records released it in England in 1981. The title song, “Street Parade,” was released as a single in New Orleans and became an annual favorite of the Mardi Gras festivities.

“We’re famous for our parades,” King confirmed. “We’ll have a parade for anything, even for a funeral. People don’t realize that second line means just what the name says. These social and pleasure clubs have their own members, so they’re part of this parade. The second line is the other people following behind the parade. They used to line up behind these parades for blocks, for miles. They’d be banging on stuff, shaking beans, making that second-line rhythm.”

During this period, 1965-1974, King rarely performed in public. Instead, he stayed behind the scenes, writing and producing songs for other people. In this way, he resembled Willie Dixon, the great writer-producer of the Chicago blues scene. Dixon, too, never enjoyed much success with his own recordings, but he wrote and arranged big hits for Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Little Walter and is now recognized as the secret genius behind the stars. King is due the same recognition.

In fact, one could argue that King, Dixon, Percy Mayfield, and Chuck Berry are the true “Poets of the Blues.” All four made their recording debuts between 1945 and ’55; all four compensated for a lack of higher education by educating themselves to become verse craftsmen; all four satirized American life and romance with an unerring eye.

All of them, even Berry, are better known for the dozens of versions of their songs by other artists than for their own recordings.

“When I got into my own thinking about writing,” King confessed, “my intention was to be the best lyricist in the world. I used to sit around with my buddies, drinking coffee and talking about how something in a song could be said a different way. We used to get a kick out of playing gymnastics with the words. We’d talk about what kind of thought that's going to create in the person who's listening. We’d talk about words that might have a twofold meaning to them. Like ‘Do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti; forget about the dough and think about me.’”

King had better luck the following year when he cut “A Mother's Love” for Specialty Records and scored a Gulf Coast hit. The song sounded so much like King’s mentor that many jukeboxes attributed the song to Guitar Slim. The label on the record itself was supposed to read “King Earl,” a DJ's nickname for the young singer, but the pressing plant got it wrong and printed it as “Earl King.” That’s what he's been called ever since. Photograph by Michael P. Smith ©The Historic New Orleans Collection.

King was that increasingly rare figure in American life — the non-academic intellectual. He never attended school again after graduating from Booker T. Washington High School in New Orleans, but he never stopped studying and reading. A conversation with King was likely to take unexpected detours into Asian music, marketing theory, modern jazz, and the Rosicrucian Order. He was living proof that an active, well-stocked mind doesn’t always come with scholarly credentials.

“I went through high school, but I didn’t stop there,” he recounted. “My ex-girl friend was a schoolteacher, and she used to say, ‘Earl, you live in the library worse than I do.’ I said, ‘I’ve got to go to the library when I want to know something. I don’t care how many days it’s going to take me; when I want to know something, I’m going to dig it out.’ I’m like that with everything, though … I’m going to go full force with it. Many years ago, when I played the racehorses, I used to go to the library to learn everything I could about horses. That’s my nature.”

Earl King performing on the Polaroid stage on Sunday, April 30 at 6 p.m. at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, Friday, April 28 through Sunday, May 7, 1995. Photograph by Michael P. Smith ©The Historic New Orleans Collection.

King got back to live performing when a young rock band called the Rhapsodizers (later known as the Radiators) convinced him to join them on stage at The 501 Club (now known as Tipitina's) in 1974. The warm response from a younger audience reinvigorated King, and he started hanging out in the clubs again. Then he met Hammond Scott, the future owner of Black Top Records.

“I had come down here to go to Tulane Law School,” Hammond Scott recounted, “and I already knew who Earl was and what he looked like, because I was a devoted record collector. Within a few weeks of being in New Orleans, I happened to be at the red light at St. Charles and Louisiana, and just as I was pulling off, standing there at the bus stop was Earl King. There was no doubt — the hair and everything made it obvious.

“I pulled over, rolled my window down and said, ‘Hey, it looks like Earl King. Where you going? I’ll give you a ride.’ Well, Earl's real friendly, so he got into the car, and what was supposed to be a short ride turned into a several-hours affair. I liked Earl so much that I started going to look for him at his hangouts. Then it got to be that whenever Roomful of Blues came to town, he’d go see them, and they’d always make him get up and play.

“One night Earl was playing with Roomful and I said, ‘Damn, this is as good as it gets.’ By that time, I was an assistant DA and was running my record company on the side. The idea just snapped that night that it could be a great thing musically to record Earl with Roomful. … They sound so good together, and if Earl could write some new tunes, they could make a record and even play some dates together. It was hard, though, because I’d take Earl home from the sessions at 5 in the morning, and I’d have to be in front of a judge at 8:30.”

Black Top released “Glazed” by Earl King and Roomful of Blues in 1986, followed by two more solo albums from King, 1990's “Sexual Telepathy” and 1994's “Hard River To Cross.” All three albums were well received, and the invitations poured in from nightclubs and festivals around the world. Suddenly, King was touring more in his 50s and 60s than he ever had in his 20s and 30s.

The Black Top albums also gave King a chance to go back and revisit some old songs. He was finally able to record “Those Lonely, Lonely Nights” with all the instruments in tune. The Imperial single, “Your Love Means More To Me Than Gold,” was given a fatter, fuller arrangement. Most importantly, “Time for the Sun to Rise,” was rescued from its sloppy treatment on the 1977 album for the Sweden's Sonet label, “That Good New New Orleans Rock ‘n Roll.” The new version of “Sexual Telepathy” gave the chiming guitar figure an incandescent clarity and gave King’s most evocative lyrics a spellbinding vocal.

“One of my best songs in public gigs, overseas, everywhere, is ‘Time for the Sun to Rise,’” King insisted. “If I play with a new band, the first thing they ask me is, ‘Earl, we’re going to play “Time for the Sun To Rise,” aren’t we?’ I say, ‘Yeah, we’re going to rehearse that.’ That's one of my better songs. It describes a person fantasizing about how they would like it to be but they know it can’t.

“That's one of my drone songs. I was inspired by the drone because I was a Ravi Shankar fanatic. I used to listen to him all night long. When Shankar plays the sitar, he lets the drone resonate off the other strings, but I don’t let the drone do what it wants to do. I make the drone go rhythmically the way I want it to go. We always think of the blues as a Western culture, but from listening to the modes Shankar plays on, I think the blues are an Eastern culture.”

As welcome as it was to hear King revisit some of his best songs from the past, it was even more heartening to hear him come up with superb new songs. The usual pattern for pop-music writers is that the songs just pour out of them in their 20s and then they spend the rest of their careers trying to match the power and ease of their initial outburst. That's because most songwriters rely on visits from the muse, and the muse comes by a lot less often once you get tied up with a career and a family.

For a writer like King, however, who relied on diligence rather than happenstance, the songs kept coming. The Black Top albums unveiled some of his best compositions: “It All Went Down the Drain,” “Sexual Telepathy,” and “Love Rent.”

“Earl has written a little differently in every decade,” claimed Hammond Scott. “He doesn’t rest on his laurels. It’s not like he has one sound and everything else is a derivation of that. Every 10 or 15 years, there’s a complete washout of everything that was the old structure, and there’s a totally new sound.

“Earl takes a lot of pride in his songwriting thing. That’s the thing that keeps him going. He’s had a lot of ups and downs. He’s had a lot of little hustles to keep himself going; he placed bets at the racetrack; he had a little record store; he knows how to cut hair. Most of the time, Earl was a behind-the-scenes guy in New Orleans. He had periods, whenever he had a hit, that he went out on the road, but that wasn’t his main thing. The thing that gives him his place and who he is is his songwriting.”

King and Hammond Scott had been planning the singer's fourth Black Top album for some time, but their work was interrupted when King almost died. In May of 1998, a trip to the hospital revealed that his body was on the verge of a total collapse.

“I had got to the point where I was drinking every day like it was nothing,” King admitted. “And I wouldn’t get drunk. That was what was so bad about it. If I had got plastered, that would have been cool; it might have slowed me down. But I wouldn’t know I was drunk, so I would sit up there all day and put it away. I was drinking so much that I lost my appetite and I wasn’t eating no food.

“I got sick and Hammond said, ‘You might have pneumonia,’ so we checked it out. I’m glad we did, because it was bad. But it wasn’t anything I couldn’t stop. Once I realized I had to stop drinking, I just did it. I’m a die-hard. And once I left the drinking alone, the appetite came back and I started eating again. People say, ‘Earl, what are you doing drinking an O’Doul’s?’ I say, ‘That’s what it is.’”

The afternoon after our dinner at Frankie and Johnny’s, King, the Scotts, and I drove down Dryades and LaSalle Streets, the once busy center of Black New Orleans.

From the back seat, King conjured up the way the streets appeared in the ’50s and ’60s — the barber shops and haberdasheries were full of folks making themselves look good for Saturday night; busking musicians and portrait photographers crowded the sidewalks as joyfully raucous music poured out of the bars. But as we drove down the street all we saw were sad buildings with peeling paint and boarded windows and sadder people, stumbling down the sidewalk in third-hand clothes and a painful, needy look in their eyes.

“Driving down there today,” King allowed, “it's like a different world. It’s depressing, because I know how it was. Yesterday, I was on the phone with some of my buddies — Smokey Johnson, Robert French, and Isaac Bolden — and we went to reminiscing about all these clubs we used to go in. Robert said to me, ‘Earl, all these places are gone. All these youngsters around here, they just don’t want to listen to what the music's about. They think they know it all and they don’t.’ I said, ‘Yeah, what they’re missing [is what] we had when you went to the Dew Drop. At the Dew Drop, you could hear every major musician in the nation and play with every musician in New Orleans.”

There's a danger that King’s creative legacy could be lost to history in much the same way the Dryades and LaSalle Street scene has. That would be a shame, for King has written some of the smartest, catchiest, sturdiest songs to ever come out of Louisiana.

Fighting against that danger is the evidence that more and more young blues bands are adding King’s songs to their repertoire. No one has been more devoted to this cause than Greg Piccolo, the former leader of Roomful of Blues.

After dinner at Frankie and Johnny’s, we drove up River Road to Southport Hall where Piccolo was leading his own quintet. As soon as he spotted us up front in the cavernous, wooden dancehall, the singer with the black beret and black jacket informed the audience, “We have a legend in the house tonight. Earl King!”

A few songs later Piccolo jumped into "It All Went Down the Drain,” which he later declared “my favorite song by one of my favorite songwriters.” King closed his eyes and nodded along to the beat, as if mentally comparing his original version with Piccolo’s variation. When the song was over, he opened his eyes and smiled.

Epilogue: Less than four and a half years after this interview, King died of diabetes at age 69 on April 17, 2003. The funeral was delayed for two weeks so it could take place on Wednesday, April 30, between the two weekends of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival.

The funeral took place at Gallier Hall, where Aaron Neville sang “Ave Maria” and Irma Thomas sang “Oh Happy Day.” Dr. John glanced inside the open coffin and told the congregation, “He’s plotting a way to come back and do whatever it is he wants to do next.”

After the funeral itself, the mourners from the church were joined by hundreds of fans for the procession from the church to the St. Louis Cemetery. King’s casket was placed in a horse-drawn hearse behind the Young Men’s Olympia Brass Band, 10 dark-suited musicians who played sober hymns such as “A Closer Walk with Thee.” Following this “first line” were more musicians, Mardi Gras Indians in all their colorful plumage and hundreds of friends and fans who formed the legendary “second line” of New Orleans folklore.

After the burial, the procession returned to Gallier Hall, but now the music was lively and joyful, as if to emphasize that we the living must put our sadness behind us and live our remaining lives to the fullest before it's our time to ride in the hearse.

And that’s how we should look at Earl King. It’s a drag that he died so young without the greater recognition he deserved. But we have his wonderful music, and we should enjoy that to the fullest while we can.

~ Watch Earl King perform the Guitar Slim classic, “The Things I Used To Do” ~

Earl King: “Time for the Sun to Rise” (from “Sexual Telepathy” (Black Top, 1990)) This is not a typical King tune, but its sheer harmonic beauty and emotional intensity makes it his best. Working with that trademark New Orleans 12/8 rhythm, he constructs a gorgeous repeating guitar arpeggio and then contrasts it against a guttural blues vocal. That dichotomy underpins the lyric that finds the singer dreaming at night about a perfect romance within a utopian society only to awake to the loveless, discordant world of the daylight. When he cries, “Sunrise, why must you come so soon?” one can hear both the romantic wish that he could live in his dreams and the stoic realization that he can’t.

Professor Longhair: “Big Chief” (“Part 1” from “Mardi Gras in New Orleans” (Mardi Gras, 1987); “Part 2” from “Fess: The Professor Longhair Anthology” (Rhino, 1993)) This tune is so closely associated with the legendary Professor Longhair that few people realize that King not only wrote it but also handled the vocal and the whistling on the original 45. That 1964 single on Watch Records came in two parts: an instrumental “Part 1” that featured Fess’s trademark piano lick and Wardell Quezergue’s classic horn arrangement and a vocal “Part 2” dominated by King. Fess later re-cut the song several times with his own vocal, and the Neville Brothers and the Subdudes also took their turns, but no one could match the original single, the best ever example of New Orleans second-line rhythms.

Earl King & Roomful of Blues: “Those Lonely Lonely Nights” (from “Glazed” (Black Top, 1987)) The biggest hit of King’s career was this song, which became a Gulf Coast hit as an Ace single in 1955 and sold a reported 250,000 copies. It has since been recorded by Dr. John, Warren Storm, Fernest Arceneaux, Johnny “Guitar” Watson, and Katie Webster & Lonnie Brooks. King's original version was striking but notoriously out of tune, and he didn’t give the song its definitive version until his fruitful collaboration with the Rhode Island jump-blues outfit, Roomful of Blues. The mesmerizing, two-chord vamp perfectly sets up the wailing vocal of desire and despair.

Levon Helm & the RCO All-Stars: “Sing, Sing, Sing (Let's Make a Better World)” (from “Levon Helm & the RCO All-Stars” (ABC, 1977)) It’s difficult to write an anthem that makes people want to sing along, and it’s just as hard to write a funky tune that makes people want to dance. This is one of the rare numbers that does both at once. The plea for social tolerance and cooperation has been recorded by Dr. John, James Booker and King himself, but the definitive version comes from Helm and his All-Stars, which included Dr. John, Booker T & the MGs, and Paul Butterfield, as well as Helm's former Band-mates, Robbie Robertson and Garth Hudson.

Earl King: “A Weary Silent Night” (from “Sexual Telepathy” (Black Top, 1990)) King rewrote “Those Lonely Lonely Nights” many times, but this was the best variation, almost as good as the original. He did it as a 1958 single for Ace, but this remake is the best version. The familiar melody now supports the story of a man who comes home to find his woman has absconded without warning. You can hear the astonishment in King's voice and the sting in his brilliant guitar solo. The song ends with a stanza of Smokey-Robinson-like metaphors, “What is a ship without its crew, what is the morning without the dew, what is the sky without the blue, what is my life, girl, without you?”

The Jimi Hendrix Experience: “Come On (Let the Good Times Roll)” (from “Electric Ladyland” (Reprise, 1968)) “Come On” is one of those rock 'n' roll standards like “Louie Louie” and “Wooly Bully” that are so primitive and so irreducible that they’re learned by garage bands and bar bands everywhere. It has been recorded by Stevie Ray Vaughan, Pee Wee Crayton, Anson Funderburgh, and King himself, but it enjoyed its finest moment when Hendrix turned it into a vehicle for some of his fiercest blues-rock jamming.

The Meters: “Trick Bag” (from “Funkify Your Life: The Meters Anthology” (Rhino, 1995)) The Meters were New Orleans’ version of Booker T & the MGs, an astonishingly tight instrumental quartet. Seldom was their brand of ‘70s funk better showcased than on this rare vocal number, the title cut from their 1976 album. The King composition highlights the staggered syncopation of New Orleans second line in a riveting guitar/piano figure that sets up a comic narrative about a man who complains that his two-timing lover has “put me in a trick bag.” The song has been cut by Robert Palmer, Ronnie Barron, and King, but no one funked it up more than the Meters.

Earl King & Roomful of Blues: “It All Went Down the Drain” (from “Glazed” (Black Top, 1987)). This song boasts not one but two unforgettable riffs — a low chordal rumbling in the piano and baritone sax and a high, prickling figure by the lead guitar. Pushing and pulling at each other, these two riffs evoke the tension of the crumbling relationship described in the lyrics. When that strain becomes almost unbearable, King releases it in a wonderful descending melody as he sings in surrendering despair, “Like a sewer when it rains, it all went down the drain for you and me.” It has been recorded by Boz Scaggs, Guitar Shorty, Tom Principato, and Toni Lynn Washington, but no one did it better than King himself.

Lee Dorsey: “Do-Re-Mi” (from “Wheelin’ and Dealin’: The Definitive Collection” (Arista, 1997)) King enjoyed his highest chart success when Dorsey took this infectious 1961 Fury single into the pop top-30. It was an obvious follow-up to Dorsey's previous hit, “Ya Ya,” with its infectious, sing-along tune and bouncy beat. In typical King fashion, though, he replaced the nonsense lyrics of “Ya Ya” with a delicious pun and a satirical comment on finance and romance: “Do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti; forget about the dough and think about me.” Dusty Springfield also did a terrific version.

Earl King & Roomful of Blues: “Love Rent” (from “Glazed” (Black Top, 1987)) This swing-blues staple from King's live show takes a wickedly satirical look at older men wooing younger women: “Your battery ain’t too strong, and your tire needs air. No jump for free, you gotta pay the fee. Get you some green presidents; you’re gonna need them to pay love rent.”

Earl King: “Sexual Telepathy” (from “Sexual Telepathy” (Black Top, 1990)) This is a crisp swing number that might have come from the Basie Band, though it’s unlikely the Count could have come up with these lyrics about lusty, long-distance vibrations.

Earl King: “Street Parade” (from “Street Parade” (Charly, 1981), also “Mardi Gras in New Orleans” (Mardi Gras, 1981) Every February in New Orleans, you hear this 1972 Kansu single blasting out from jukeboxes and French Quarter balconies once again, because few songs capture the hip-wiggling bacchanalia of Mardi Gras better than this carnival anthem. When King sings, “I get excited with every beat of the drum … we’re going to go dancing, dancing out in the street,” the music produces the same reaction in the listener.

Geoffrey Himes has written about pop music in The Washington Post since 1977 and has served as a senior editor at No Depression and Paste magazines. Himes has written award-winning journalism on music and the arts for numerous outlets including Rolling Stone, Oxford American, New York Times, Smithsonian, National Public Radio. He wrote a book on Bruce Springsteen, Born in the U.S.A., and liner notes for albums by Rosanne Cash, Merle Haggard, the Isley Brothers, the Beach Boys, Bill Withers, Ray Wylie Hubbard, Billy Bragg, Marty Stuart, Beau Jocque, Earl King, and others. He’s working on a book about Emmylou Harris, Rosanne Cash, Rodney Crowell, and Ricky Skaggs for the Country Music Hall of Fame. He has lived in Baltimore since 1974.

Michael P. Smith (1937-2008) worked as a freelance photographer for the prestigious Black Star photographic agency for more than 20 years. He co-founded the New Orleans music club Tipitina’s in 1977. During the 1980s, Smith traveled to Cuba, where he photographed many of the same subjects he explored in New Orleans: neighborhood life, street music, and religious practices.